Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The Great

Imperial

Scramble

525

whole

territory

northward

to

Egypt,

eastward

to

the

Italians

in

Somali-

land,

and

westward

to

the

Congo

Free

State

and

the

watershed

between

the Nile

and

the

Congo

rivers.

Germany

also

consented

to

a

British

protectorate

in

Zanzibar.

A

wit

described the

transaction

by

saying

that

Britain

had

exchanged

a

trouser

button for a whole suit of

clothes,

and when

the

First

World

War

came

Britons

added

ruefully,

"But

what a

strategic

button!"

A

British

invitation

to

France

to

adhere

to this

convention followed

immediately

upon

its

conclusion.

The

result

was

a

very

limited

bargain,

completed

in

five

weeks.

France

consented to

a

British

protectorate

over

Zanzibar in

return for

a

British

recognition

of the French

pro-

tectorate

over

Madagascar

and

French

influence

over the western

Sahara down

to

Lake

Chad,

where it

would

meet

the British in

Nigeria.

There was

no

attempt

to

reach a

comprehensive

agreement

comparable

to

that

with

Germany,

for

both

parties

knew that such

an

accord was

then

impossible.

The

French

could

not

yet

forgive

the

British

occupa-

tion of

Egypt,

nor

forego

the

dream

of

planting

the

tricolor on

the

banks

of

the

Nile,

somewhere,

somehow,

and

sometime,

which was

to lead

to

the

Fashoda

crisis

in

1898.

The

British advance

from

South

Africa,

to which we

now

return,

aspired

to

join

the

British

penetration

from the

east coast and then

push

on to

Egypt.

This

project

of a

continuous belt of British

territory

stretching through

the

whole

continent from

top

to

bottom

and re-

inforced

by

a

Cape

to Cairo

railway

was even

grander

than

that

of

France

to

fling

a

bridge

across the

greatest

width

of

the continent. It

was too

ambitious

for the British

government

but

not for the

master

mind of

Cecil

Rhodes,

whose name

is written

large

on

the

map

of

Africa.

It was

he

who

conceived and directed

the

advance from the

south,

through

the

open

door of

Bechuanaland;

though

he was

unable

to

carry

it far

enough

to

effect a

junction

with British

East

Africa,

he

added

Rhodesia

to the

British

Empire.

Immediately

to

the north

of

Kruger's

South

African

Republic

and

of

the

British

protectorate

of Bechuanaland

lay

the

fabled

region

of

"King

Solomon's

Mines."

There

from

time

immemorial,

natives

had

worked

gold

mines and

had

lived

by

agriculture,

for the

soil

was fertile

and

the

rainfall

good.

Moreover,

the

country

was a

high

tableland and

therefore,

though

within

the

tropics,

had

a

healthy

climate

quite

suit-

able

for

white colonization.

The southern

portion

of

this

rich and

tempting

prize

was

known as Matabeleland

because the

Matabele,

an

offshoot

of

the

Zulus,

had

conquered

it

and settled

upon

it

when

the

526

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

Boers

of

the

Great

Trek

drove

them north

across

the

Limpopo

River.

Beyond

Matabeleland and

reaching

to

the

Zambesi

River

was

Mashona-

land,

which

was

inhabited

by

the

less

warlike

Mashona

tribes,

whom

the

Matabele had reduced to

subjection.

Over

all

ruled

the

able and

despotic

Matabele chieftain or

king,

Lobengula.

The

kraal

of

this

native

potentate,

at

Bulawayo, began

to attract

concession-hunters

in

the

seventies.

The

buzzing

increased

in the

eighties,

and

it

was

wildly

excited in

1886

by

the

discovery

of

gold

on the

Witwatersrand

in the

Transvaal. This

was

the

greatest

gold

find

of

all

history,

and

it

sug-

gested

that

even

greater

riches

were to

be found

in the

kingdom

of

Lobengula.

There British and

Boers from

the

south,

Germans

from

the

west,

and

Portuguese

from

the

east

staked out

claims.

Clearly

the

Matabele were about to lose

the treasure

house

that

they

had

conquered.

Kruger precipitated

the

coming

crisis

by

dispatching

an

emissary

who,

in

the summer

of

1887,

extracted

from

Lobengula

a

treaty

that

gave

special

privileges

to

Transvaalers

north

of

the

Limpopo

under

a

resident Boer consul. The

news reached

Rhodes

before

die end of

the

year,

and he

urged

the

high

commissioner,

Sir

Hercules

Robinson,

to

proclaim

Matabeleland-Mashonaland

within

the

British

sphere

of

influence.

Robinson could not do

this without

instructions

from Lon-

don,

but as

time was

short

he rushed

the

Rev.

J.

S.

Moffat,

assistant

commissioner

in

Bechuanaland,

off to

Bulawayo

to

protect

British

interests

there. Moffat

easily

persuaded

the Matabele

king,

in Feb-

ruary

1888,

to

repudiate

the Transvaal

treaty,

which

he later said had

been

got

from

him

by

fraud,

and

to

affix his

mark to another

with the

"Great

White

Mother"

binding

him to enter into no

foreign

corre-

spondence

and

particularly

to cede no

territory

without

the

high

com-

missioner's

consent.

In

spite

of

angry

Transvaal

protests,

Robinson

ratified Moffat's

treat}*,

which

virtually

made

Lobengula's

dominion

a

British

protectorate.

Agents

of Rhodes and his associates

got

Lobengula

in

October

1888

to

assign

to

their

syndicate

all mineral

rights

in

his

kingdom

in return

for

1,200

a

year,

1,000 rifles, 100,000

rounds of

ammunition,

and

a

steamboat on

the Zambesi.

Having gained

this immense

concession,

Rhodes

rushed to London to

make

arrangements

for

developing

it.

He

had to

float a

company

of commensurate

size,

and

for it he

sought

a

charter

similar

to

those

recently

granted

to the

companies

controlling

North

Borneo,

Nigeria,

and British

East

Africa. At

first the

govern-

ment was

unfriendly,

and for some time

he

had to

fight

strenuous

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

527

opposition

from the

Aborigines

Protection

Society,

from

imperialists

advocating

direct

imperial

rule,

and

from

jealous

rivals.

But

at

last,

in October

1889,

he

procured

a

royal

charter for

his British

South

Africa

Company

under

certain conditions. The

company

was

to

be

directly

responsible

to the

Colonial Office

for

the

handling

of

native

affairs,

it

had

to

accept

as

some of its

directors

public

men

named

by

the

government,

it

was

obliged

to

buy

out

previous

concessionaires,

it

was to exercise

governmental powers

only

with

the consent

of

the

native

ruler,

and

it

was

liable to

have its charter

revoked

at

any

time.

Meanwhile

Rhodes was

maturing

his

plans

for

the

occupation

of

the

country.

The

first

white

settlers arrived

in

1890,

the

beginning

of

something

that is

unique.

Here,

but

nowhere else

in

all the

territories

acquired

by

European powers during

the

great

imperial

scramble,

a

considerable

white

population

took

root in

the soil.

But this is

a

story

that

belongs

to

another

chapter.

The

geographical

extent

of the

chartered

company's

dominion,

christened

Rhodesia

by

a

royal

proclamation

in

1895,

was at

first

very

uncertain.

The

charter,

adopting

the

vague

terms of

Rhodes'

applica-

tion,

defined

it as the

region

north of Bechuanaland

and

the Transvaal

and

west of

Portuguese

East

Africa. There

was

no

reference

to

limits

on

the north

or the

west,

and

nobody

knew where

this

Portuguese

terri-

tory

ended.

According

to

Portuguese

claims

that

France

and

Germany

had

recognized

by treaty

in 1886,

Portuguese

East

and

West

Africa

extended

without

a

break

from

the Indian to

the

Atlantic

Ocean,

leav-

ing

nothing

for

the

new

British

company.

On

the other

hand,

Lord

Salisbury

in

1887 had

registered

with

the

Portuguese

government

a

formal

protest "against

any

claims

not founded

on

occupation"

because

they

were

contrary

to the Act of

Berlin,

adding

that his

government

"cannot

recognize

Portuguese

sovereignty

in

territory

not

occupied

by

her

in sufficient

strength

to

enable

her

to

maintain

order,

protect

foreigners,

and control

the

natives."

After

long

and

trying

negotiations,

a

treaty

was

signed

in

June

1891

separating

Portuguese

territories

on the east

and west coasts

by

a

broad

wedge

of

British

territory

extending

up

to

Lake

Tanganyika.

All but

a

little

strip

of

this

territory,

a

total

of

nearly

half

a

million

square

miles,

was

the

empire

of the

British

South Africa

Company.

The little

strip,

running along

the

west side of

Lake

Nyasa

and

some

distance down

its

effluence,

the

Shire

River,

had

been declared

a

British

protectorate

in

1889,

when

a

force

of

armed

Arabs

under

Portuguese

leadership

528

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

invaded

it

and with machine

guns

shot

down

natives

who refused to

submit.

At the

southern end of

Lake

Tanganyika,

the

British advance

to

the

north

was

blocked

by

the

Anglo-German

convention

of

1890.

Salisbury

had an offer

from

the

Congo

Free

State

to

give

Britain a

narrow

corridor

running

up

to

Uganda,

but

he

did

not

hesitate

to

abandon this

link in

the

"All-Red

Route"

when

he found

that

it

would

probably

wreck the

negotiation

with

Germany.

The

control of the

upper

Nile

began

to

be

a

pressing

issue

shortly

afterward,

when

King

Leopold

nearly

stole

a

march

on

both

France

and

Britain. His

Congo

Free

State

was

expanding

in

this

direction,

and in

1892

an

expedition

led

by

Belgian

officers

reached

the

great

river

some

distance

below the

Victoria

Nianza

while

others

penetrated

into the

Sudanese

province

of Bahr-el-Ghazal.

London

delivered

warnings

to

Brussels,

but

the

region

at stake

was still

beyond

the

British

reach.

Uganda

was too far

inland to serve

as a base

for

any

effective

operation,

and the

Mahdi's

successor barred

an

approach

from

Egypt.

Therefore

a

bargain

was

struck,

by

the

Anglo-Congolese

convention

of

May

1894.

Leopold

recognized

the British

sphere

of

influence

as defined in the

Anglo-German

convention

of 1890 and leased

to

Britain

the

corridor

that

Salisbury

had then

abandoned,

and Britain

allowed

the

Congo

Free State to

lease the

disputed

Sudanese

province.

But both

parties

quickly

renounced their

leases,

London

yielding

to

vigorous

protests

from

Berlin

against

the

British corridor

along

the

west side

of

German

East

Africa,

and

Leopold

bowing

to

excited

pressure

from Paris

against

the

erection of a

Congolese

barrier across the French

path

to

the

Nile.

In

the

previous

year

Paris

had

ordered

an

expedition

to follow

this

path

to the river and

occupy

Fashoda,

only

to call

a

halt on

receiving

word

from Brazzaville

that

the

Belgians

threatened to

stop

the

expedi-

tion

by

force. The

wily

Leopold

was now

turning

to

play

along

with

the

French.

What

had fixed French

eyes

on

Fashoda

w

r

as

a

public

address

before

the

Egyptian

Institute in

January

1893

by

Victor

Prompt,

an

outstand-

ing

French

engineer

in

the

Egyptian

service.

Discussing

certain

hydro-

graphic

problems

of the

Nile,

he

observed that a

barrage

at

the

mouth

of

the

Sobat,

which

flows

into

the

Nile

just

above

Fashoda,

would

be

easy

to

construct and could

be

used,

along

with

dams

at the

outlets of

Lakes Victoria and

Albert

Nianza,

to

hold

Egypt

to

ransom.

Thence

came half

the

summer

supply

of

Egypt's

water,

he

said,

and the

country

would starve if this were

withheld

or be

completely

drowned

The Great

Imperial

Scramble

529

if it were

released in

a

flood.

His

words

created

a

mare's-nest

for

the

French

and

a

nightmare

for

the

British.

3

France

determined

to

seize

this

seat

of

power

before Britain

was

ready

to

do

it.

The

British

plans

called for

indefinite

delay

until

simultaneous

thrusts

could

be

launched

from

Egypt,

when the

govern-

ment

of

that

country

had

built

up

sufficient

financial

and

military

strength,

and

from

Uganda,

when

it

was

connected

with Mombasa

by

a

railway

that

had

yet

to

be

built.

While

the

British

contemplated

this

north-south

pincers

movement,

which

they

knew

would

be

impos-

sible for

several

years,

the

French

planned

a

more

immediate

east-west

pincers

movement.

Captain

Marchand

would

lead

a

military

mission

from

the

French

Congo

to

Fashoda,

while

Leopold

from

Brussels

directed

a

parallel

expedition

through

the

Congo

Free

State,

and

at

the

same

time

another

French

expedition

would

approach

the Xile

through Abyssinia,

which

Italy,

with

secret

French

connivance,

was

then

openly

trying

to

conquer.

The

key

to what

followed

lies

in

Abyssinia,

where the

Italian

army

was

floundering

and

finally

suffered

disastrous

defeat

at

Adowa

in

March

1896.

The

Italian

catastrophe

was

France's

opportunity.

It

opened

the

door

wide

for

a

French

advance

through

Menelik's

empire,

and

it

encouraged

that

triumphant

King

of

Kings

to

send

a

large

army

to seize some of the

Sudan on his

own

account,

thus

matching

the

design

of

Leopold.

But

Adowa also

revolutionized the

British

plans.

Already

rumors

of

menacing

French

activity

had shaken

Lord Cromer's

firm

opposition

to

any

Egyptian

venture into the

Sudan.

Already

the

dervishes of

the

khalifa,

whose

hostility

to

Egypt

had

been

held

in

check

by

hostilities with

Abyssinia,

were

again

swarming,

this time

not

against

their

old

Abyssinian

foes

but

in

cooperation

with

them

against

the Italians. Less than

a

fortnight

after the battle

of

Adowa,

the

cabinet

in

London ordered an

advance from

the

Egyptian

border

at

Wadi

Haifa

to

Dongola,

more than two

hundred

miles

up

the

river.

Who would

pay

for

this

expedition?

Britain

expected

that

Egypt

would.

Though

Cromer

had

no

money

for

it,

the

surplus

controlled

by

the

International Debt Commission

was sufficient and Britain

asked the

other

powers

to

sanction

an advance of

500,000.

London counted on

a

majority

decision,

but

the

Egyptian

courts

upheld

the

contention

of

3

When Marchand

got

to

Fashoda,

he found

that

Prompt

was

utterly

wrong

about the

possibility

of a

barrage

at

the mouth of

the

Sobat,

530

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

France

and

Russia that

a unanimous

decision

was

necessary,

with the

result

that the

British

government

had

to

foot

the

bill

and

thereby

became

a

partner

in the

enterprise,

which

was executed

in

the

autumn

of

1896.

That the

occupation

of

Dongola

was

only

a

preliminary

step

to the

recover}-

of

the

Sudan,

the

British

did

not

try

to conceal.

In

June

1896

Lord

Salisbury,

the

prime

minister,

told the

House

of

Lords:

"We shall

not

have

restored

Egypt

to the

position

in

which

we received

her,

and

we

shall not have

placed Egypt

in

that

position

of

safety

in which

she

deserves

to

stand,

until the

Egyptian

flag

floats

over

Khartoum."

But

who would

pay

for

this

more

expensive

undertaking,

which

might

cost

as

much

as

2,000,000?

Cairo

could

not and

London

would not as

yet.

Nor

was this

the

only

formidable

question.

What forces were

necessary

to

execute

the

larger

operation?

It

was more

than

doubtful

if

the

Egyptian

army

could do it alone.

This

meant

that

Britain would

have

to send

a

contingent

of her

own

army

to

join

in the

reconquest

of

the

Sudan,

for

which

the British

public

was not

prepared

as

yet.

Such

considerations

explain

why,

after

Dongola,

there was

no

further

Egyptian

activity

in

the

Sudan

until

1898,

except

the

building

of

a

strategic

railway

from Wadi

Haifa across the desert

to

Abu

Hamed

and its

occupation

in

August

1897.

By

that

time

Marchand had

crossed

the

Nile

watershed,

and London

was

greatly

worried over

reports

of a

definite

Abyssinian-dervish

combination and

a

French

expedition supported by

Menelik.

Two

months

later,

in

London,

the

British commander in chief

urged

an

immediate

advance

from

Abu

Hamed to Khartoum and the

government rejected

it. At

the

end

of the

year,

however,

this

decision was

reversed and

the order

was

issued.

From

all

sides

there

was

a

converging

movement on the

upper

Nile

in

the

first half of

1898,

but

only

two of

the

opposing expeditions

ever

met,

the others

becoming bogged

down. On

July

10,

Marchand,

with

half

a

dozen

European

officers

and

as

many

score

Senegalese

troops,

reached Fashoda and

there

hoisted the

tricolor. Sir

Herbert

Kitchener,

sirdar

(commander

in

chief)

of

the

Egyptian

army,

was

still

hundreds

of miles to

the

north and

not

yet

near

his

objective,

which

was

Khartoum,

across

the river

from

the

khalifa's

capital

at

Omdunnan.

It was

not

until

2

September

that

Kitchener's

force

of

22,000

British

and

Egyptian

soldiers there met and

destroyed

the

main

dervish

army

of

40,000.

This battle

of

Omdurman

was

so

decisive

that

mopping-up

operations

were

all

that

was

needed to

complete

the

conquest

of the

country.

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

5

3

1

But

Kitchener,

who

was

rewarded with a

peerage

for

his

smashing

victory,

had

first

to

deal

with

Marchand,

six hundred

miles

up

the

river. On the

7th a

native

steamer

came

down

the

river

and

was

stopped

near

Khartoum.

On

being questioned,

the

crew

said

that

white

men

had

fired

on

them at

Fashoda.

That

was

Kitcheners

first

intimation that

the

French

were

there. On the 19th

he was there too.

His

arrival

probably

saved

the

little French

force from destruction.

It

had

repelled

one

dervish

attack

but was

expecting

a fiercer one

at

any

time. Now

Marchand

refused to

retire

or to haul down his

flag

without

orders

from

home;

Kitchener

contented himself

with

hoisting

the

British

and

Egyptian

flags;

the two men

agreed

that

it

was

not their

business

but

that

of their

governments

to

resolve

the

clash

of

claims;

and Kitchener

ended

the

amicable

meeting

by inviting

Marchand to

join

him in a

whisky

and soda.

The

Fashoda

crisis

nearly

plunged

Britain and

France into

war. The

tide

of

British

imperialism,

having

reached a new

height during

the

Diamond

Jubilee

of

the

previous

year,

rose

higher

still

when the tele-

graph

reported

the

triumph

at

Omdurman. The whole

country

seemed

to

have

gone

mad with

glory.

At

the end of

September,

in

the

midst

of

the

hysterical

rejoicing,

news of the

Fashoda

incident

arrived,

and the

press

began

to

rage

against

France

for

trying

to

steal the fruits of

the

British

victor}

7

.

The

government,

which

had

repeatedly

warned

France

to

keep

hands off

the

Nile,

flatly

refused

to

discuss French

claims until

the Marchand

mission

had

been

withdrawn. France had

to

give

in. She

was in

no condition

to

wage

foreign

war,

for

she was

then

trembling

on

the brink

of

civil war between

the

Dreyfusards

and

the

Anti-Dreyfusards.

But the abusive

tone

of the

British

press

and the

uncompromising

stand of

the British

government

made it

almost

impossible

for the

French

government

to back down,

October was

a

month

tense

with naval and

military

preparations

on

both

sides of

the

Channel.

There

was

panic

in

France

but

not in Britain. To France it

seemed

that

Britain

was bent on

provoking

war

to settle

accounts,

of

which

there

were

many,

once

and for all. France

looked to her

one

ally,

Russia,

for

support;

and

the

heads

of

the czar's

foreign,

finance,

and

war ministries

arrived

in

Paris for

secret discussions.

They

de-

parted

leaving

the

French

government

hopeless.

The French

decision

to

capitulate

came

early

in

November.

Discussions

could then

proceed,

and

in

March

1899

the two

governments

signed

an

agreement

that

drew

a

dividing

line

between

their

spheres

of influence north

of the

Congo

Free

State.

The

line

excluded

France from

the

whole

basin of

532

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

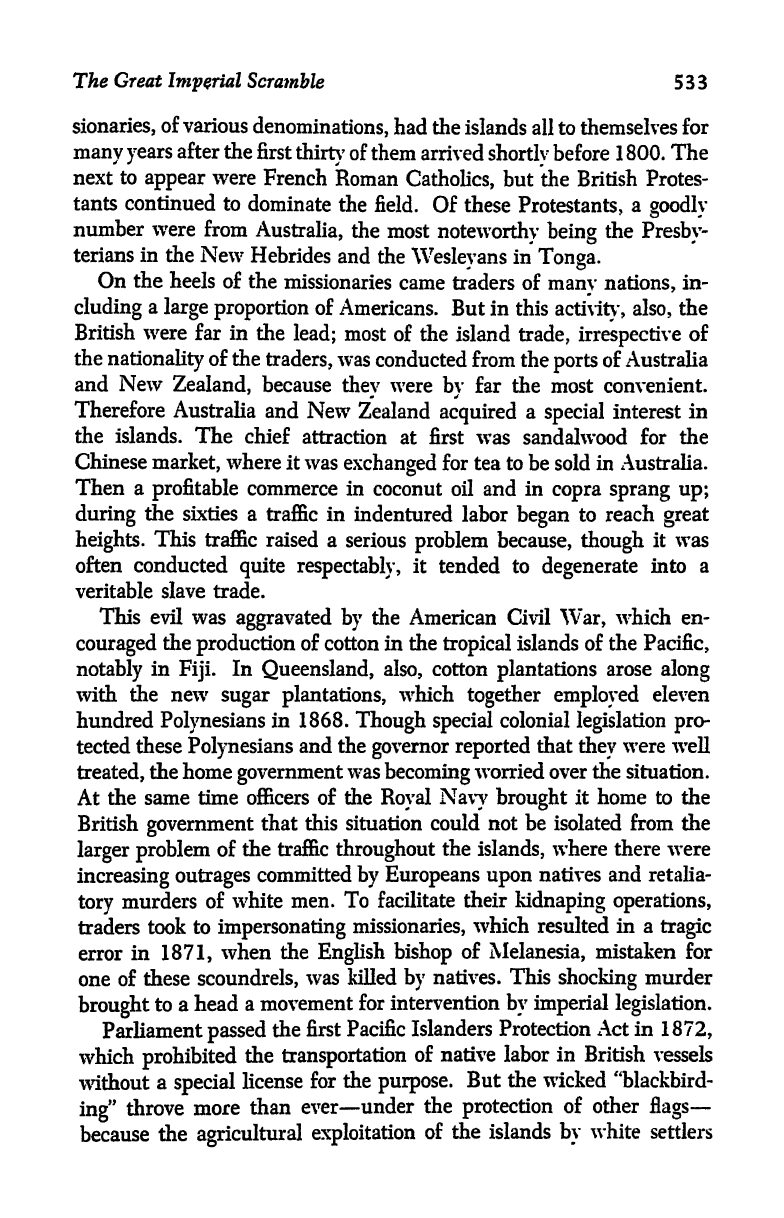

South

Pacific

Islands

before

First

World

War

the

Nile.

Already,

in

January,

the status of the Sudan

was

formally

settled

by

the British and

Egyptian

governments.

As

the

country

was

conquered

by

"the

joint military

and financial efforts"

of Britain and

Egypt,

they

were to share

sovereignty

over

it. This condominium

was

to be

a

bone

of contention

between

the two

governments

when

Britain

finally

evacuated

Egypt.

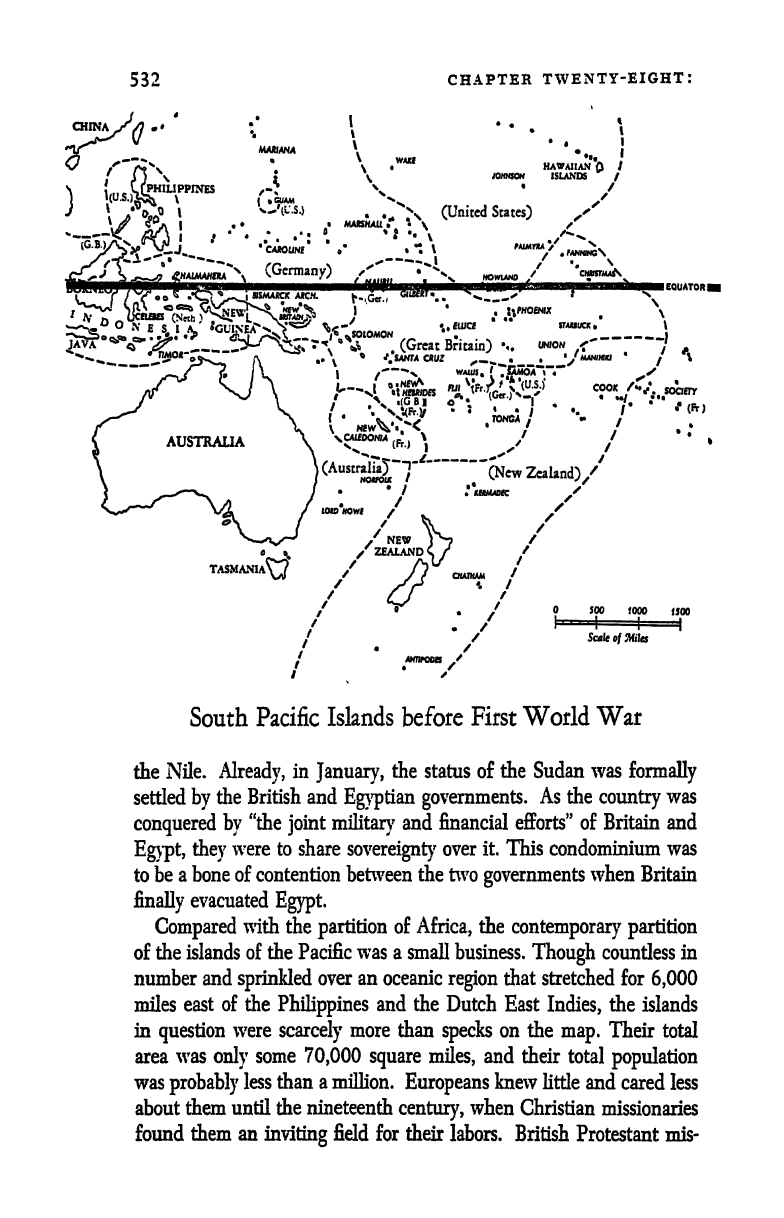

Compared

with

the

partition

of

Africa,

the

contemporary partition

of the islands of the

Pacific was a small business.

Though

countless

in

number and

sprinkled

over

an

oceanic

region

that

stretched for

6,000

miles

east

of

the

Philippines

and the

Dutch East

Indies,

the

islands

in

question

were

scarcely

more than

specks

on the

map.

Their total

area

was

only

some

70,000

square

miles,

and their

total

population

was

probably

less

than a

million.

Europeans

knew

little and

cared less

about

them until the

nineteenth

century,

when

Christian

missionaries

found

them

an

inviting

field

for

their

labors. British

Protestant

mis-

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

533

sionaries,

of

various

denominations,

had the

islands

all

to themselves

for

many years

after

the

first

thirty

of

them arrived

shortly

before

1

800.

The

next

to

appear

were

French

Roman

Catholics,

but the

British Protes-

tants

continued

to

dominate

the

field. Of these

Protestants,

a

goodly

number

were

from

Australia,

the

most

noteworthy being

the

Presby-

terians

in

the

New

Hebrides

and the

Wesleyans

in

Tonga.

On

the

heels

of the

missionaries

came traders of

many

nations,

in-

cluding

a

large

proportion

of

Americans. But in this

activity,

also,

the

British

were

far in

the

lead;

most

of the island

trade,

irrespective

of

the

nationality

of the

traders,

was

conducted

from

the

ports

of Australia

and

New

Zealand,

because

they

were

by

far the

most

convenient.

Therefore

Australia

and New

Zealand

acquired

a

special

interest

in

the islands.

The

chief

attraction at

first was

sandalwood

for

the

Chinese

market,

where

it

was

exchanged

for tea

to

be

sold

in

Australia.

Then a

profitable

commerce in

coconut oil

and

in

copra sprang

up;

during

the sixties a

traffic

in

indentured labor

began

to

reach

great

heights.

This traffic

raised a

serious

problem

because,

though

it was

often

conducted

quite

respectably,

it

tended

to

degenerate

into

a

veritable slave trade.

This

evil was

aggravated by

the American Civil

War,

which

en-

couraged

the

production

of cotton in

the

tropical

islands

of

the

Pacific,

notably

in

Fiji.

In

Queensland,

also,

cotton

plantations

arose

along

with the new

sugar

plantations,

which

together

employed

eleven

hundred

Polynesians

in 1868.

Though

special

colonial

legislation pro-

tected

these

Polynesians

and the

governor

reported

that

they

were

well

treated,

the

home

government

was

becoming

worried over

the

situation.

At

the same

time officers

of the

Royal

Navy

brought

it home to

the

British

government

that

this situation could not

be isolated

from

the

larger

problem

of

the traffic

throughout

the

islands,

where

there

were

increasing

outrages

committed

by Europeans

upon

natives and retalia-

tory

murders

of

white

men.

To facilitate their

kidnaping operations,

traders took

to

impersonating

missionaries,

which

resulted

in a

tragic

error

in

1871,

when

the

English

bishop

of

Melanesia,

mistaken for

one

of

these

scoundrels,

was killed

by

natives. This

shocking

murder

brought

to

a

head

a

movement

for

intervention

by imperial

legislation.

Parliament

passed

the

first

Pacific

Islanders Protection Act in

1872,

which

prohibited

the

transportation

of

native

labor

in

British

vessels

without

a

special

license

for

the

purpose.

But

the wicked

"blackbird-

ing"

throve

more

than

ever

under

the

protection

of other

flags

because

the

agricultural

exploitation

of

the

islands

by

white settlers

534

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

was

gathering

momentum and

forcing

up

the

price

of labor.

The next

British

action

to

cope

with the

evil

was

the

annexation

of

the

Fiji

Islands in

1874,

not

to

forestall

other

powers

but,

as

we

have seen in

a

previous

chapter,

because no

other

power

would take

them.

Following

this

move,

the British

government

had

parliament

pass

the second

Pacific

Islanders Protection

Act

in

1875,

which

went a

great

deal

further than the first.

The

new

act

provided

for

a

high

commissioner,

with

headquarters

in

Fiji,

and

a

special

court

of

justice

to

exercise

jurisdiction

over

all

British

subjects

in

the

islands

of the

Pacific

outside

the

dominions of

any

civilized

power.

With

the

exception

of the

Marquesas

Islands,

Tahiti,

New

Caledonia,

and

the

Loyalty

Islands,

which France

had

already

annexed,

all

the

archipelagos

of

Polynesia,

Micronesia,

and

Melanesia

thus

passed

under

a

qualified

British

pro-

tectorate,

the

qualification

being

that

it affected

only

British

subjects

in

these islands

and

that it

made

no claim

to bar

annexations

by

other

powers.

Still

the nefarious

traffic

continued,

as

it

was bound to do

until

the

power

vacuum

was

filled.

Germany

started

the scramble

to divide

up

the

islands,

but

the main

pressure

behind

British

participation

in

it came from

Australia and

New

Zealand.

Their

interest

in

preserving

their

general

trade

in the

islands,

which

annexation

by

other

powers

would

cut

down,

and

their

concern

for

their own

security,

which

might

be

seriously

threatened if

other

powers

established

themselves

in

nearby

islands,

as France

had

done

in

New

Caledonia,

made

them more and more

impatient

with

the

mother

country's

opposition

to

any

British

annexations

in the

Pacific.

As in South

Africa,

so also

in

die

South

Pacific there

was

strong

colonial

pressure

for

British

imperial expansion.

New

Guinea,

the second

largest

island

in the

world,

is

separated

from

the

northern

tip

of

Australia

by

the island-studded Torres Strait.

Because

its waters

were

perilous

for

navigation

and

were

on the shortest

route

from

New South

Wales

to

India

and

China,

the British

Admiralty

had

the

strait

surveyed

in

1846.

The

officer

in

charge

of tie

work then

took

possession

of

the

adjoining

New

Guinea coast

for

Britain,

but

London disavowed

his

action. In

1873

it was

repeated,

with

the same

negative

result,

by

another

British

naval

officer,

Captain

Moresby,

who

was

engaged

in

trying

to

suppress

the

illegal

labor traffic.

By

this

time,

however,

there

was a

Queensland

settlement on the

southern

side of

the

strait;

the

operations

of

pearl

fishers

were

extending

to the

opposite

shore;

and

Australians

generally

were

beginning

to

display

a

lively

interest

in the

great

island. The

west

half had

long

belonged

to

the