Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The Great

Imperial

Scramble

535

Dutch,

but the

eastern

half

was

still

unappropriated

by any power.

Its

annexation

by

Britain,

to

make

sure it

would

not fall

into

foreign

hands,

was

formally

proposed

by

the

government

of

New

South

Wales

in 1875. The

home

government,

having

found

Fiji

a heavier

financial

burden

than

anticipated,

refused to

consider

the

proposal

unless

the

Australian

colonies

would

share

the

expense,

which

they

declined

to

do.

Therefore the

subject

was

dropped, only

to

spring

up again

in

1878,

when

rumors

of

gold

drew

a

flock

of adventurers

to

eastern

New

Guinea

and

the

high

commissioner

reported

that

the annexation

of

at

least

part

was

inevitable.

This time the

failure

and withdrawal of

the

prospecting

parties

gave

a

respite

to

the

Colonial Office.

Ominous rumors

of

an

impending

foreign

occupation

of

eastern

New

Guinea

began

to

fly

around in 1882. Various

powers

were men-

tioned,

particularly

Germany,

in which

country

there was

a

public

agitation

for

the

annexation and

colonization

of

this "vacant" land.

In

February

1883

Queensland

cabled

London,

urging

British

annexation

before

it was too

late,

and

offering

to

bear

the

cost

and to take formal

possession

on

the

receipt

of

authority by

cable. Gladstone's

colonial

secretary replied

that such an

important question

required

careful

consideration.

Early

in

April

the

Queensland

government

had

one

of

its officials

proclaim

at

Port

Moresby

the

annexation

"pending

decision"

in

London,

hoping

thereby

to commit

the

home

government.

The home

government

not

only

declined to

approve

but

it also

rebuked

the

govern-

ment of

Queensland

for

assuming

a

power

it

did

not

possess.

More-

over,

the

colonial

secretary's

crushing

dispatch

declared

that

the

fears

of

foreign

occupation

were "indefinite

and

groundless";

that in

any

event

annexation

to

Queensland

would be

open

to

objection,

which

was

an intimation that

the record

of

Queensland

did not

qualify

her

for

taking

charge

of

the

native

population

in

New

Guinea;

and that

a

forward

policy

in the

Pacific

must

wait

upon

effective collaboration

by

the

Australian

colonies

generally.

The

last

remark soon

found

an

application

in

Victoria,

when that

colony

urged

the

annexation

of all

the islands

between New

Guinea

and

Fiji, including

the New

Hebrides

w

7

hich

were the

special object

of

this

proposal.

For

thirty

years

British

and colonial missionaries

had

toiled in

the New

Hebrides

which,

lying

close to

New

Caledonia,

were

under

a French

shadow.

In

1878 the

British

and French

governments

agreed

to

respect

the

independence

of

these

islands,

but

of late

years

there

was a

growing

apprehension

in Australia

that France

would

seize

them. Hence

the

Melbourne demand

for

their annexation

by

Britain.

536

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

The

British

response,

in

August

1883,

was to

persuade

France

to

renew

the

mutual

assurance.

Toward

the

end

of

1883,

an intercolonial

convention

met in

Sydney

and

adopted

unanimously

a number

of resolutions

on

Pacific

questions.

One

of

them

was

that

the "further

acquisition

of

dominion in

the

Pacific

south

of

the

equator, by

any foreign

power

would

be

highly

detrimental to

the

safety

and

well-being

of

the

British

possessions

in

Australasia,

and

injurious

to

the

interests

of

the

empire."

On

the

basis

of

this

broad

principle,

the

delegates

pressed

for the

immediate

annexa-

tion

of

eastern

New

Guinea

and

requested

the British

government

to

open

negotiations

with

France

with the

purpose

of

securing

control

of

the

New

Hebrides

in the

interests

of

Australasia.

They

also

undertook

to

recommend

to their

respective

governments

the

appropriation

of

funds

to

support

this

Pacific

policy.

The

colonial

governments

whose

representatives

so

eagerly

called

for

the

tune were

much less

eager

to

pay

the

piper,

with the result

that

they

lost

part

of the

tune. In

the

late summer of

1884,

when the

British

cabinet

had

just

decided

to establish

a

protectorate

over eastern

New

Guinea

with

Australian

financial

support

of

15,000

a

year,

Germany

intervened

with

an

intimation that

she

would

take

the

northern

side

of

the

territory.

As

Bismarck

had

the

whip

hand in

Egypt

and in

other

parts

of

Africa,

London shrank

from

offending

Berlin

and

decided to

limit the

protectorate

to

the

south

side of the

island. The

British

procla-

mation

was

issued

in

November,

just

in

time to block

a

scheme

under

cover

of

the

French

flag.

In

December

Bismarck

announced the

raising

of the

German

flag

in northern

New

Guinea.

Australians

raged

at

the

mother

country

for

being

so

blind

and so

timid,

and

London

turned to

negotiate

with

Berlin a

delimitation

of

boundaries

between

British

and

German

spheres

in

the

Pacific.

There the

race

was

now

on.

The

British

protectorate

of New

Guinea,

4

with

an

area

of

90,000

square

miles

and

a

population

of

some

400,000,

was

annexed

as

a

colony

in

1888;

in 1901 it

was

turned

over

to the

newly

federated

Australia,

which

renamed

it

the

Territory

of

Papua.

In

spite

of

con-

tinued

Australian

anxiety

to

get

the New

Hebrides,

Britain

would

take

no

step

to

acquire

them.

By

a

convention

of

1887,

following

a

serious

4

The

British

government

appointed

an

administrator

for New

Guinea

and

put

him

under

the

governor

of

Queensland

who,

with

the

advice

of his

executive

council,

was

to

exercise

general

supervision

over

the

protectorate

subject

to

conditions

prescribed

for

the

protection

of

the natives.

The

15,000

mentioned

above

was

provided

by

Queens-

land,

New

South

Wales,

and

Victoria,

each

paying

5,000.

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

537

native

outbreak,

they

were

placed

under

the

protection

of

a

joint

Anglo-French

naval

commission.

Britain,

Germany,

and

the

United States

made a somewhat

similar

arrangement

for

the

Samoan

Islands

in

1889. For

many years

New

Zealand had

pressed

Britain

to annex

them,

but Britain would

not;

now

a

dangerous

situation

had

developed

in

these islands.

A

disputed

succession

to the

native

throne

led

to

a

civil

war

in

1887,

and

Germany

supported

one

claimant

while

Britain and

the

United

States backed

his

rival.

Heaven

intervened at a

crucial moment in March

1889.

A

German

and an

American

squadron

were

apparently

on the

point

of

coming

to blows

when

a

terrific hurricane

burst,

sinking

all the German

and two American

warships,

and

strewing

the

wreckage

on

the

beach

of

Apia.

It was

under the

sobering

influence

of this sudden

disaster,

which

caused

a

heavy

loss

of

life,

that the

three

powers

combined

to

stop

the

civil

war

and

establish

their

collective

control

over

the islands.

But

their

partnership proved

to be an

uneasy

one,

the

pacification

of

the

islands

was

only partial,

and

the death of

the

native

king

in

1898

produced

another civil

war

with the same division

between

the

powers.

In

March 1899 British

and

American

ships

bombarded

Apia,

damaging

the

German

consulate.

Germany

was intent on

dividing

the islands

with the

United

States,

and

proposed

compensation

for

Britain in

the

neighboring

Tonga

Islands;

but

London,

mindful

of New Zealand

and

Australian

interests

in

Samoa,

refused to

agree,

even

when

Germany

threatened

to

form

a

European

combination

against

Britain.

Finally,

in

the autumn

of

1899,

the

coming

of

the Boer War

forced London

to

bow

to

Berlin

in

Samoa.

Elsewhere

in

the

broad

reaches

of

the

Pacific,

the international

game

of

give-and-take

had

been

regulated

by

fairly

amicable

agreement

among

the

interested

powers;

and

now,

with

the

partition

of

Samoa,

practically

all

the islands

of

this immense

region

were under

the

sovereignty

of

some

western

power.

In

total

area

and

population,

Germany gained

most,

with Britain

a

good

second.

Much

behind came

France

and

the United

States,

France

collecting

more

square

miles

but

less

population

than

the

United

States.

This,

of

course,

is not

counting

the

Philippines,

which

were

the

prize

in a

very

different

game

and

made

American

gains

in

the

Pacific

many

times

greater

than those of

Germany.

More

than

a

hundred Pacific

islands,

with a combined

area

of

some

22,500

square

miles

and

a

population

of

approximately

330,000,

were

added

to

the

British

Empire

between

1884

and

the end of

the

century;

many

of

these

islands

were

placed

under

the control of

New

538

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

Zealand,

which

thus became

the

seat

of

a

sprawling

minor

island-

empire.

Turning

back

toward

southeast

Asia,

we

come

upon

the

third

largest

island

in

the

world,

5

Borneo,

where

Dutch

and

English

traders

established

themselves

in

the

seventeenth

century

but

neither nation

got

a

real

footing

until

the

nineteenth

century.

Then

the

Dutch took

three

quarters

of

the island.

The

remainder,

the

north

and

the north-

west,

was

formally

placed

under

British

protection

in

1888,

when it

was

already

under

effective

British

control.

Most

of

this

territory

once

belonged

to

the

sultan

of

Brunei

who,

by

successive

grants,

ceded

it

into British

hands.

The

first

cession

was

to

a remarkable

Englishman,

James

(later

Sir

James)

Brooke,

a

retired

officer

of

the

East

India

Company's

army

and

the

son

of

a

wealthy

member

of

the

Company's

civil

service.

A

voyage

to

China

through

die

Malay

Archipelago

fired

him

with

an ambition

to

rescue

the

warring

and

piratical

island

tribes

from

their

savage

barbarism.

Returning

to

England,

this

rich

and

practical

Don

Quixote

fitted

out

and

trained

a

private

expedition,

with

which

he

sailed to

Borneo.

There

he

aided

the sultan to

suppress

a

tribal

revolt

in the

province

of

Sarawak,

and

for

this service

the sultan

made

him

raja

of

Sarawak

in

1841.

He

spent

all

his

private

fortune

in

building

up

his

little

principality,

introducing

a

civilized

code

of

laws,

recruiting

a

civil

sendee

of

Englishmen,

stamping

out

savagery,

and,

with the

occasional

assistance

of

British

ships

of

war,

suppressing

the

piracy

that

was

a curse

to

the

native tribes

that

engaged

in

it as well as

to western

shipping

in

the

neighboring

seas.

His

enlightened

administration

drew

immigrants

from

other

parts

of

Borneo and

won

him

official

recognition

by

the British

government

as

an

independent

ruler.

After

his death

in

1868,

his

nephew

and

heir,

Sir Charles

Brooke,

proved

to

be

a

worthy

successor.

Under

these two

rajas,

Sarawak

grew

to

be

many

times

its

original

size,

the sultan

of

Brunei

ceding

the additional terri-

tory

in

return

for

annual

money payments.

British

North

Borneo

had

a

later

and different

origin.

In 1881 the

British

North Borneo

Company

received a

royal

charter and

acquired

the

territorial

rights

that the sultans

of

Brunei

and Sulu had ceded to

a

syndicate

three

years

before.

It was the first

of the new

chartered

Companies

which,

patterned

somewhat

after

the

defunct East

India

Company

but

without

any monopoly

of

trade,

were

organized

to

de-

&

Greenland

and

New

Guinea

are

larger.

Ttie Great

Imperial

Scramble

539

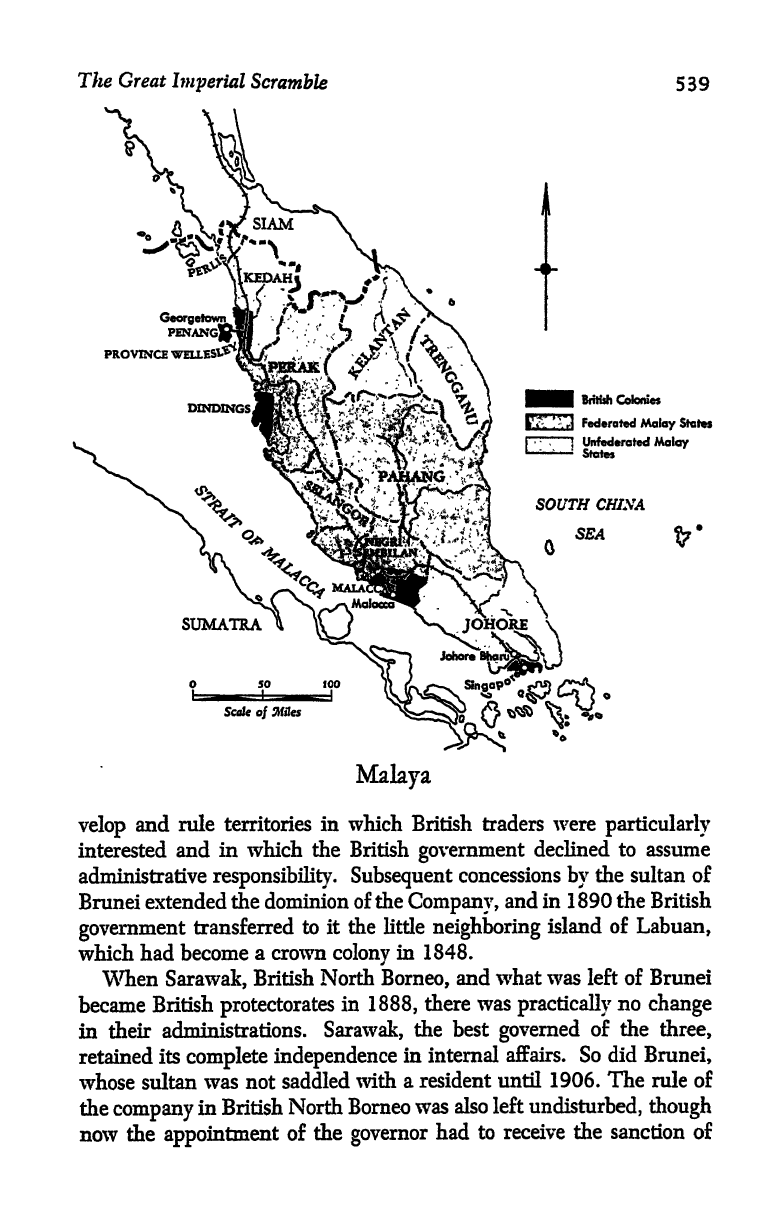

British Colonies

Federated

Malay

States

Unfederated

Malay

States

SOUTH

CHLVA

SEA

Malaya

velop

and

rule

territories

in

which

British traders

were

particularly

interested

and

in which the

British

government

declined to assume

administrative

responsibility.

Subsequent

concessions

by

the sultan of

Brunei

extended

the

dominion

of

the

Company,

and

in

1890

the

British

government

transferred to

it the little

neighboring

island

of

Labuan,

which

had become

a

crown

colony

in

1848.

When

Sarawak,

British

North

Borneo,

and

what was left of

Brunei

became

British

protectorates

in

1888,

there

was

practically

no

change

in their

administrations.

Sarawak,

the best

governed

of the

three,

retained

its

complete

independence

in internal

affairs.

So

did

Brunei,

whose

sultan

was

not

saddled

with a

resident

until 1906. The rule of

the

company

in

British

North

Borneo

was

also left

undisturbed,

though

now

the

appointment

of

the

governor

had

to receive

the sanction

of

540

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

the

colonial

secretary.

The

partition

of

Borneo

between

the

Dutch

and

the

British,

completed

by

a

boundary

treaty

of

1891,

was

uncon-

nected

with

the

international

competition

that

carved

up

Africa

and

distributed the

Pacific

islands

among

the

western

powers.

On

the

Asiatic

mainland,

the

expansion

and consolidation

of

the

British

position

in

the

Malay

Peninsula

likewise

stands

apart

from

the

race

between

the

imperial

powers.

Here

the

British

advance

was

rather a

repetition

of

what

had

happened

in India

during

the

days

of

the

Company.

When the

Crown

"took over"

from

the

East

India

Com-

pany

in

1858,

the

Straits

Settlements,

comprising

Singapore,

Malacca,

Penang,

and Province

Wellesley,

were

virtually

stranded.

They

had

long

been a

heavy

drain

on

the

treasury

of

the

Company,

and

now

that

they

came under

the

new

India Office

with no

change

in

the

form

of

the

administration,

they

were

in

a

sorry plight.

They

had

no

money

for

fighting

the

local

plague

of

piracy

or for

recruiting

a

competent

civil

service,

to

say

nothing

of

providing

for

other immediate

needs

or

future

development.

Their

trade

was with

China,

and

they

had

practically

nothing

in

common with

India,

except

in

the new

department

of

government

created

in

London

to look

after the

affairs

of

India.

Local

agitation

for freedom from this

artificial

tie became

very

strong,

until

in

1867

the

Straits Settlements were

transferred

to the

Colonial Office

and became a

crown

colony

with

their

own

separate government.

The

nine

years

of

stagnation

were over.

The

Straits

Settlements were

the

foundation of British

Malaya,

and

the next

stage

in

the

building

was

the addition

of

the

Federated

Malay

States:

Perak,

Selangor,

Negri

Sembilan,

and

Pahang.

The

native

states of

the

peninsula

were

seething

with

civil

wars

which

spilled

over

their

boundaries,

and

the

Straits

of

Malacca were

infested

with

pirates.

The

obvious cure

for

this

growing

anarchy,

so

dangerous

to

British

life

and

property,

was British

intervention,

and

the

Singapore

Chamber

of

Commerce was

eager

for it.

But

the

government

of

the

colony

in-

formed

the

Chamber in

August

1872

that it

was

contrary

to

British

policy

"to

interfere in

the affairs

of the

Malay

States

unless

where

it

becomes

necessary

for the

suppression

of

piracy

or

the

punishment

of

aggression

on our

people

or

territories";

and

the

message

added

a

warning

"that,

if

traders,

prompted by

the

prospect

of

large

gains,

choose

to

run

the risk

of

placing

their

persons

and

property

in the

jeopardy

which

they

are

aware

attends

them in

these

countries

under

present

circumstances,

it

is

impossible

for

Government

to

be

answer-

able

for their

protection

or that

of

their

property."

Then

fierce

fighting

The

Great

Imperial

Scramble

541

broke

out

among

40,000

Chinese tin

miners in

Perak,

who

dyed

their

banners

in

the

blood

from

the

slit

throats of

their

victims,

defied

the

local

Malay

chief,

and

tried

to

blow

up

Chinese

houses

in

neighboring

Penang.

In

the

following

year,

1873,

London sent

out

a

new

governor

to

Singapore

to

inaugurate

a

new

policy.

He

was

instructed to

employ

British

influence

"with the

native

princes

to

rescue,

if

possible,

these

fertile

and

productive

countries

from

the ruin

which must

befall

them

if the

present

disorders

continue

unchecked." To

this

end,

he was

directed to

aim at

the

establishment

of

British

official residents

in

the

native

states.

Almost at

once he

found

his first

opening

an

invitation

to settle a

dispute

over

the

throne

of Perak.

Repairing

thither

he met

some of the

leading

chiefs in

January

1874;

with

them

he

concluded

a

treaty,

making

one

of

the

claimants

sultan

and

providing

for

a British

resident at

his

court.

Unfortunately

the first

resident

assumed too

much

authority

with

too

little

tact.

Malay spears

thrust

through

the

flimsy

walls of a

bathhouse

soon

disposed

of

him,

necessitating

a

puni-

tive

expedition.

The

sultan,

who

was

privy

to the

murder,

was

exiled,

the actual

murderers were

hanged,

a

more discreet

resident

was in-

stalled,

and

Perak

got

a

native

government

that was a

model

for that

part

of the

world.

Selangor

had

a

sultan

who was

more

interested in

horticulture

than

in

ruling.

While

tending

his

princely

garden

with

meticulous

care,

he

allowed

his

rajas

to run riot.

In the

autumn

of 1873

retainers

of one

of

these

rajas

seized

a

departing

Malacca

vessel,

murdered the

occu-

pants,

and then

brazenly

visited

Malacca,

where

they

were

arrested.

The aesthetic sultan was

shocked and

alarmed. He

consented to have

the criminals returned for

trial and

exemplar}' punishment,

he

sent

his creese

(Malay

dagger)

for

their

execution,

he

paid

damages,

and

with

the

concurrence of his chiefs he

accepted

a

British

adviser,

of

whom

he soon

reported

that the

people rejoiced

in his

presence

"as in

the

perfume

of

a

flower."

Thus,

from

1874,

Selangor

ceased

from

troubling

and settled down

to

enjoy peace

and

prosperity.

It took

longer

to settle

affairs in

Negri

Sembilan,

for it

was

then not

a

single

state but

a

grouping

of

nine diminutive

ones,

all

given

to

dis-

order.

There

British

intervention

began

in

1874,

and

it was

fifteen

years

before

the little

fragments

were combined in

a

federation

under

one

native

ruler

with

a

British resident to

guide

him in

the

way

he

should

go.

Pahang,

the

largest

state in

the

peninsula,

was a

more

difficult

prob-

542

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

lem.

The

ruler,

who

had

seized

the

throne

from

his

nephew,

was a

ruthless

and

grasping

tyrant,

and

he was

a

danger

to

his

neighbors

as

well

as

to his

subjects.

In

1887

he

was

persuaded

to

enter

into

a

treaty

with

the

governor

of the Straits

Settlements

by

which,

in

return

for

British

recognition

of his

taking

the

coveted

title

of

sultan,

he

admitted

a

British consular

agent.

But

the new

sultan

was

the

same

old

sinner.

In the

following

year,

after

instigating

the

murder

of

a

Chinese

British

subject,

he

had

to

accept

the

tutelage

of

a British

resident,

who

faced

more than one

rebellion

before

law and

order

were

finally

established.

Much

of

his

trouble

arose

from

the

suppression

of

slaver)

7

,

upon

which

the British insisted

in all four

states.

In

1895,

Perak,

Selangor,

Negri

Sembilan,

and

Pahang

were federated

with one

civil

service

under

a

resident-general,

whose seat

was Kuala

Lumpor,

the

capital

of

Selangor.

Johore,

having

a

respectable

government,

was

left

without a

British

agent

until

1914,

though

in

1885

its sultan

placed

himself

under

British

protection.

It

is

one

of the

Unfederated

States.

The

others

were added

by treat}'

with Siam

in

1909:

Perlis,

Kedah, Kelantan,

and

Trengganu.

The

treaty

cleared

up

an

anomalous

situation

in

these

states and also

in

Siam.

These states

were ancient

dependencies

of

Siam

but

lay

within

a

recognized

British

sphere

of influence.

The

first

three

were

administered for the

native

rajas by

British officers in the

service

of Siam

and

were in a

flourishing

condition.

Their

population,

mixed

like that

of most states

of the

peninsula,

was

predominantly Malayan.

Trengganu

was

quite

different. It had

a

population

that

was

almost

wholly

Malayan

and

a

government

that

had

almost ceased to

exist.

The

sultan

was

a

religious

recluse,

there were neither

written

laws

nor

courts

nor

police,

and

everyone

did what

was

right

in

his

own

eyes.

It

was the

only peninsular

state

that was

still

sunk

in

hopeless

anarchy.

In

Siam,

as

in

other

eastern

lands,

westerners were

protected

by

treaty

from

being

tried in

any

but

their

own

consular courts.

As

this

deroga-

tion of

sovereignty

had

grown

irksome to the

government

in

Bangkok,

a

bargain

was

struck

in the

treaty

of

1909,

by

which

British

consular

jurisdiction

in Siam

was

abolished

and

Siam

transferred

to

Britain

"all

rights

of

suzerainty, protection,

administration,

and

control"

of

the

four

Malay

states.

The transfer

took

place

without

disturbance,

and

Britain

installed

an

adviser

in

the

court

of

each

nominal

ruler.

The

only important

change

was in

Trengganu,

and

there

it

was

most

wholesome.

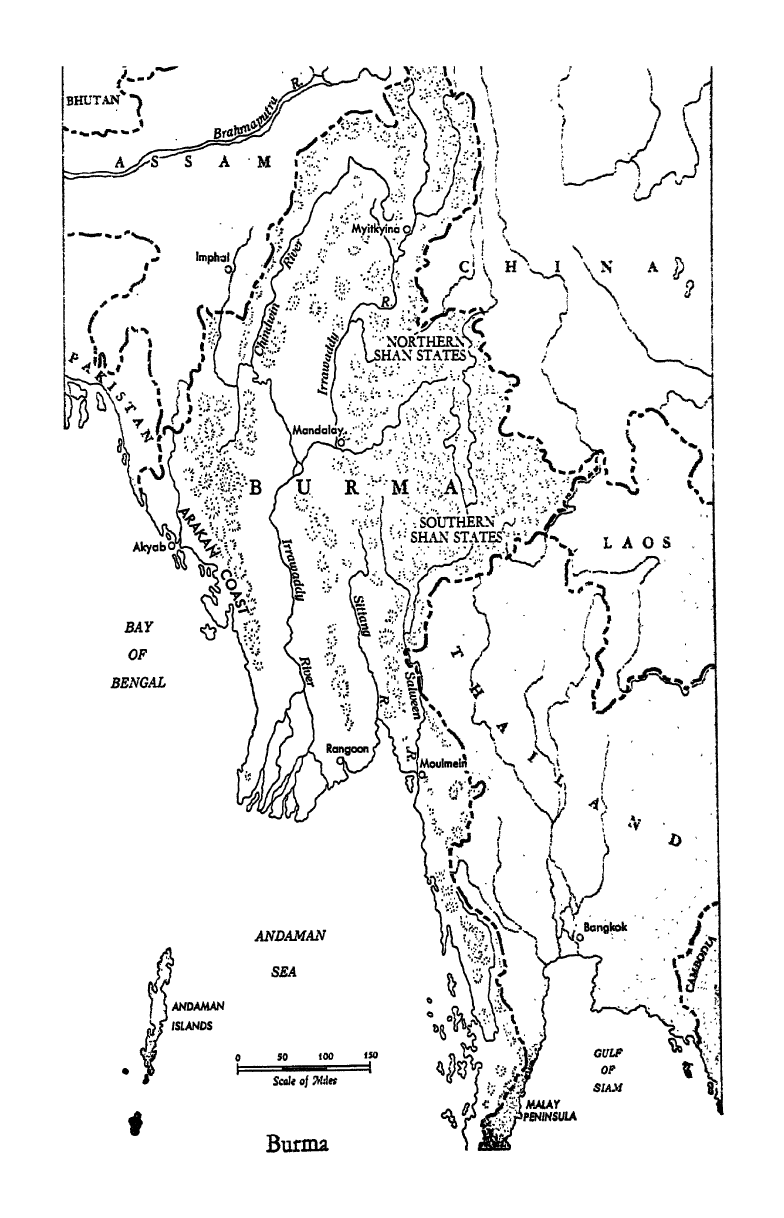

The

British

conquest

and

annexation

of

Upper

Burma,

in

contrast

to

the British

acquisitions

in

Borneo and

the

Malay

Peninsula,

had a

SOUTHERN

rJ

SHAN

STATES^*':

ll

Burma

544

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT:

direct

connection

with

the

scramble

between

the

powers. Upper

Burma

was

the

truncated

independent

kingdom

of

Burma,

which was

cut

off from

the

sea

by

the

annexation

of

Pegu,

or Lower

Burma,

to

India at

the

close

of

the

Second

Burmese

War

in 1852.

The

king

who

lost

that

war

straightway

lost

his

throne

to

a

shrewd

brother,

who

kept

him

in

captivity

for

the rest

of

his

life.

The

British

presented

a

peace

treat}

7

to the

usurper,

but

he refused

to

accept

it because

he

feared

damnation

as

a

king

who

signed

away

territory.

Pegu

thus

passed

from

one

sovereignty

to

another

without

any

formal

cession,

and

it was

not

until

1862 that

the

government

of

India

was able to

establish

diplo-

matic

relations with

the

government

in

Mandalay,

the

new

capital

of

independent

Burma.

Then

trade with

Upper

Burma was

opened,

and

presently

British steamers were

running

up

the

Irrawaddy

River from

Rangoon

to

Mandalay.

The shrewd

king

died

in

1878,

leaving

53

wives,

110

children,

and a

will

designating

the

succession.

This was

broken

by

a

palace

revolution,

which

put

Thibaw

on

the throne.

Early

in

1879,

to

prevent

his own

overthrow

by

one of

his

royal

brothers,

he

had

nearly

eighty princes

and

princesses

murdered.

Such

massacres

had stained

the

annals

of

Burma,

but

not since the

coming

of the

telegraph;

and the

butchery

did

not

stop

in 1879. The outside

world

was

horrified,

and Burma

groaned

under

the

vicious

rule of

the

mon-

ster. The

government

of

India

withdrew its

representative,

lest he

too

be

murdered;

and British Burma

was menaced

by

the

growing anarchy

across

the

border. The

unanimous

cry

of

non-officials

in

Rangoon

was

for

immediate

intervention

in,

and

annexation

of,

the

nightmarish

land.

British officialdom

was deaf

to this

cry

until

France,

having

just

carved out

an

empire

in

Indochina

that

approached

the

back

door of

Thibaw's

kingdom,

tried to

dominate it

by peaceful

penetration.

Thi-

baw

was

the

tempter.

He sent

his

envoys

to Paris

and

there,

in

January

1885,

the French

foreign

minister

signed

a

treaty

with

them;

in

addi-

tion,

he

gave

them

a

secret letter

promising

a

supply

of

arms.

Shortly

thereafter,

both in

Paris

and

in

Mandalay,

French

concessionaires

negotiated

the

building

of a

railroad,

the

establishment of

a

bank,

and

the

control

of

the

royal monopolies

in

Burma,

the

revenues

of the

kingdom

being

pledged

for

the

financial

security

of all

these

enter-

prises.

Before

the

signature

of

the

treaty'

in

Paris,

the

British

ambas-

sador warned

the French

foreign

minister that

Britain

had

special

interests

in

Upper

Burma,

and

the

latter

assured

him

that

he

would

never

permit

the

import

of

arms

into

that

kingdom.

Seven

months