Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

unsaturated bonds. The resulting lipid hydroper-

oxides, peroxy radicals, and hydroxyl radicals cause

rancidity and are potential DNA-damaging agents. A

variety of epoxides and aldehydes are also formed,

including malondialdehyde, a potential mutagen

(Figure 2).

Food Additives and Contaminants

0036 Food additives and contaminants (including pesticide

residues) are compounds that are added to food at

some point during its production. Exposure to these

substances can be controlled, and the introduction of

new chemicals used in food manufacture falls under

government regulation. Older additives or chemical

contaminants are also reviewed periodically for

exposure and health effects.

0037Use of the preservatives nitrite, butylated hydroxy-

anisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT)

as food preservatives has been controversial. Nitrite

enters the diet both through its use as a common food

preservative and through gut microbe-mediated reduc-

tion of nitrate from ingested vegetables. Nitrite cycles

from the gut to the saliva and can react at acidic pH

with amines, amino acids, phenols, and mercaptans,

frequently resulting in the formation of mutagenic

(nitroso) compounds. Mutagens can also be found

in the smoke of nitrite-treated meat during frying.

The formation of 2-chloro-4-methylthiobutanoic

O

O

3-Hydroxyflavone general structure

CH

2

CH

NH C

COOH

O

O

OH

O

CH

3

Ochratoxin A

N

Structural backbone of

pyrrolizidine alkaloids

O

O

O

Psoralen

O

O

O

O

O

OCH

3

Aflatoxin B

1

OH

COOH

NH

NH

2

Hydrazinobenzoic acid

OH

O

O

HO

OH

O

OH

OH

Ptaquiloside

OH O

OH

O

OH

OH

Altertoxin I

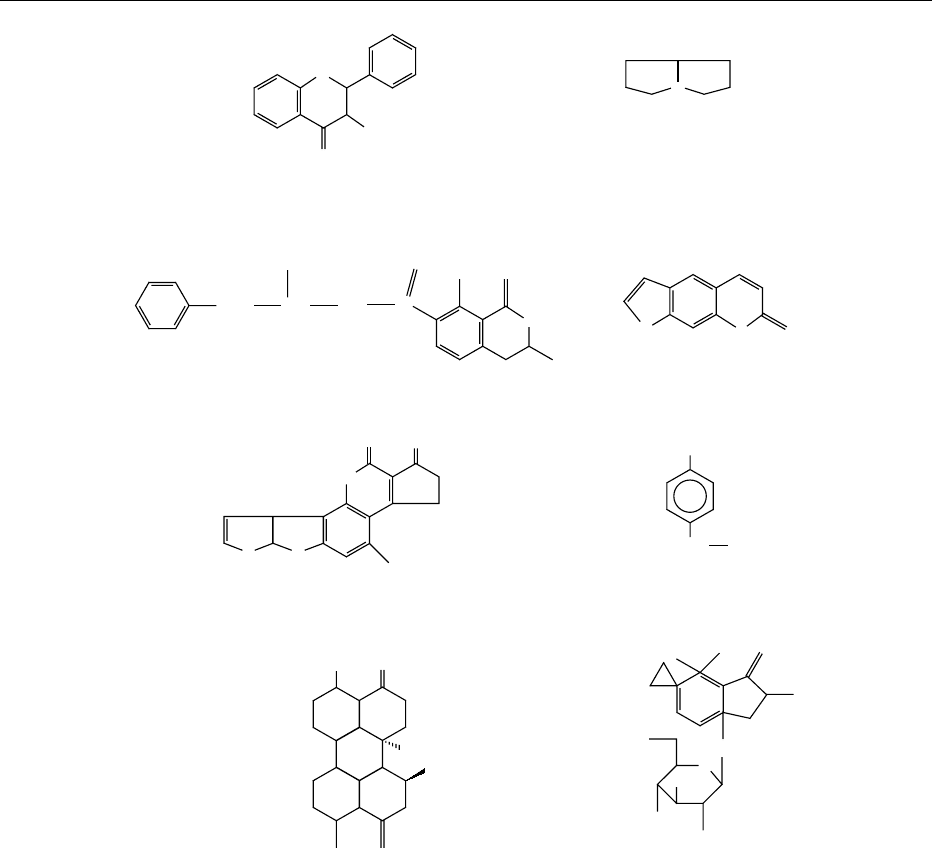

fig0001 Figure 1 Structures of selected naturally occurring mutagens.

4064 MUTAGENS

acid, a mutagen in salted, pickled fish, has also been

linked to nitrite. BHA and BHT have been added to

foods and packaging as synthetic antioxidants. Previ-

ous concerns over BHA’s carcinogenic risk to humans

appear unwarranted and related to the large doses

used in rodent-feeding studies. BHT increases the

proliferation of pretumor liver cells in rodent models

but has little effect on normal cells.

0038 The artificial sweeteners saccharin and cyclamate

have also been shown to have mutagenic properties,

although saccharin-induced bladder carcinogenesis in

rodents also appears to result from the large doses

used. Also, the mutagenicity of some colors has led to

their use being banned, although low levels of extract-

able mutagenic contaminants have been detected in

others. Mutagenic heterocyclic amino acids have

been found in some flavors.

0039 Contaminants may occur in food as residues of

pesticides and fungicides, solvents, or compounds,

such as styrene leaching from packaging material.

The persistent organochlorine pesticide toxaphene

has been found in rural foods consumed by indigen-

ous peoples in the Arctic region, having been carried

and deposited through airborne transport from sites

in the south.

Mutagens in Water

0040Drinking water provides another potential source

of mutagenic compounds. Water disinfection by

chlorination can produce many types of mutagenic

chlorinated organic compounds, of which 3-chloro-4-

(dichloromethyl)-5-hydroxy-2-(5H)-furanone (muco-

chloric acid, MX) is the most potent. Other mutagenic

chlorinated butenoic acids, including EMX (the re-

duced form of MX), brominated trihalomethanes,

and dichloroacetonitrile, are also produced. Dichlor-

oacetonitrile is a direct-acting mutagen and induces

DNA-strand breaks in cultured human lymphoblastic

cells. Other less potent mutagenic disinfection by-

products include dichloroacetic acid, trichloroacetic

acid, and chloral hydrate. Radioactive contamination

can also contribute mutagenic activity in areas where

water is contaminated with

40

K or uranium and

thorium decay products (such as radon).

Mutagens in Feces

0041Human feces have been found to contain a class of

mutagenic compounds known as fecapentaenes, the

major forms of which are fecapentaene-12 and

fecapentaene-14. These compounds appear to be

synthesized by intestinal bacteria and are lipid-sol-

uble, direct-acting base pair and frameshift mutagens.

Fecapentaene-12 also causes increased sister chroma-

tid exchanges, HGPRT mutagenesis, and oxidative

damage. Bile salts have been shown to augment the

ability of fecapentaenes-12 and -14 to induce DNA

repair in bacteria, underscoring their possible role in

colon carcinogenesis associated with high-fat, low-

fiber diets.

Prevention and Modification of Mutagen

Formation

0042A well-balanced diet also provides many compounds

that can decrease exposure to mutagens. Studies con-

sistently show that a greater consumption of fruits

and vegetables is associated with a lowering of cancer

incidence. These compounds can act at all levels of

mutagenesis by: (1) preventing mutagen formation

and acting as antioxidants, (2) deactivating muta-

genic compounds, and (3) inducing detoxifying

enzymes or inhibiting monoxygenase activity.

0043Several natural antioxidants, such as ascorbic acid,

b-carotene, a-tocopherol, polyphenolic acids, flavo-

noids, and other plant phenolics have a direct muta-

gen-scavenging activity. For example, in addition to

neutralizing oxygen radicals, many of these com-

pounds inhibit the formation of nitrosamines by com-

peting with the amine group. Mutagenic agents may

N

N

N

CH

3

NH

2

IQ

N

N

H

3

C

NH

2

CH

3

N

N

8-MeIQx

N

N

N

NH

2

CH

3

PhIP

N

CH

3

NH

2

CH

3

N

H

Trp-P-1

Benzo[a]pyrene

N

CH

3

N

O

N-Nitrosodimethylamine

H

3

C

H

2

N

C OC

2

H

5

O

Urethane

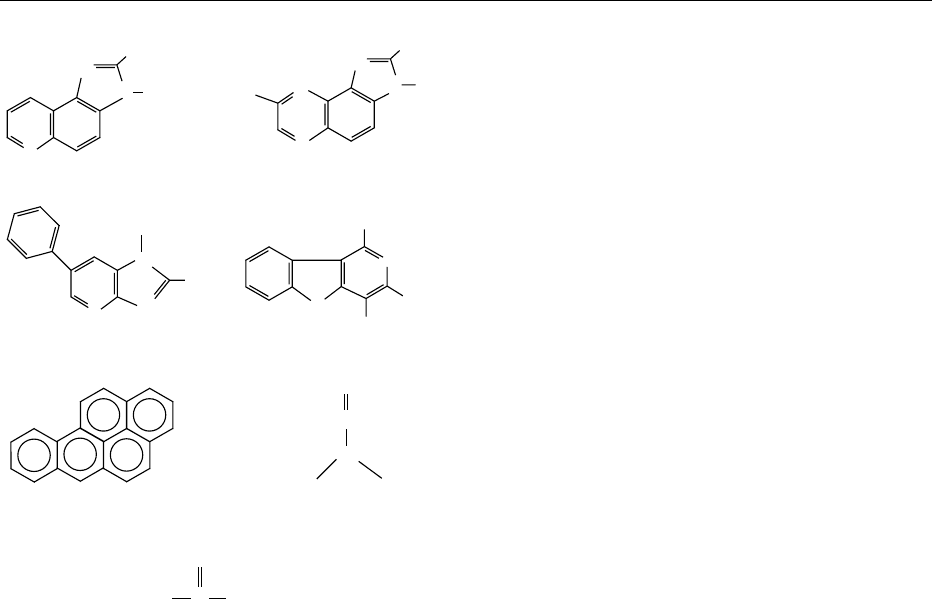

fig0002 Figure 2 Structures of selected mutagens formed during

grilling and processing.

MUTAGENS 4065

be inactivated through the formation of complexes

with calcium, casein, chlorophyl and carbonyl com-

pounds. Some evidence suggests that calcium can

inhibit familial colon carcinogenesis through inhib-

ition of lipid peroxidation. Both iron deficiency and

excess have been associated with oxidative DNA

damage, and zinc deficiency causes chromosome

breaks. The activity of glutathione-dependent detoxi-

fication systems is increased by selenium and diallyl

disulfide, from garlic, cysteamine, cysteine, as well as

a variety of phenolic compounds. Monooxygenase

activity and the formation of reactive compounds

can be inhibited by phenolic acids, free fatty acids,

flavonoids, and other polyphenols, methylxanthines,

vitamins, and biogenic amines. Conjugated dienoic

isomers of linoleic acid are antimutagenic compounds

in extracts of fried ground beef and dairy products

that appear to act through signal-transduction path-

ways and prostaglandin synthesis. Tannins or poly-

phenols in green tea have been found to be

antimutagenic in some assays, but the effects appear

to depend upon the dose and timing of exposure.

Several other compounds have shown antimutagenic

activity, including b-diketones, catechins, lignans,

and isoflavones. Finally, dietary fiber can complex

with mutagenic compounds and limit their uptake.

0044Mutagenic effects resulting from altered DNA me-

tabolism can also be influenced by diet. Adequate

intake of essential nutrients such as folate, vitamin

B

12

and vitamin B

6

aids nucleotide synthesis and

prevents DNA-strand breakage. Niacin, methyl-

xanthines, and some phenols have been attributed to

promotion of DNA-damage repair (Figure 3).

Further Considerations

0045Much work remains to completely characterize the

role of food-associated mutagens and antimutagens

in human carcinogenesis. Despite the magnitude and

frequency of exposure to these compounds, they

C

C

C

C

CH

2

OH

O

O

HO

HO

HC

HO H

L-Ascorbic acid

(Vitamin C)

(CH

2

)

3

C

C

(CH

2

)

3

(CH

2

)

3

CH

3

C

CH

3

HO

H

3

C

CH

3

O

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

HHH

α-Tocopherol

(Vitamin E)

β-Carotene

(provitamin A)

HOOC

C

NC NC

NH

2

N

OH

N

N

N

HH O H H

H

CH

2

CH

2

HOOC

Folic acid

H

3

CCH

3

CH

3

CH CH C CH CH CH C CH CH

CH

3

CH

3

H

3

CCH

3

CH

3

CH CH CCH

CH

CH CH C CH CH

CH

3

CH

3

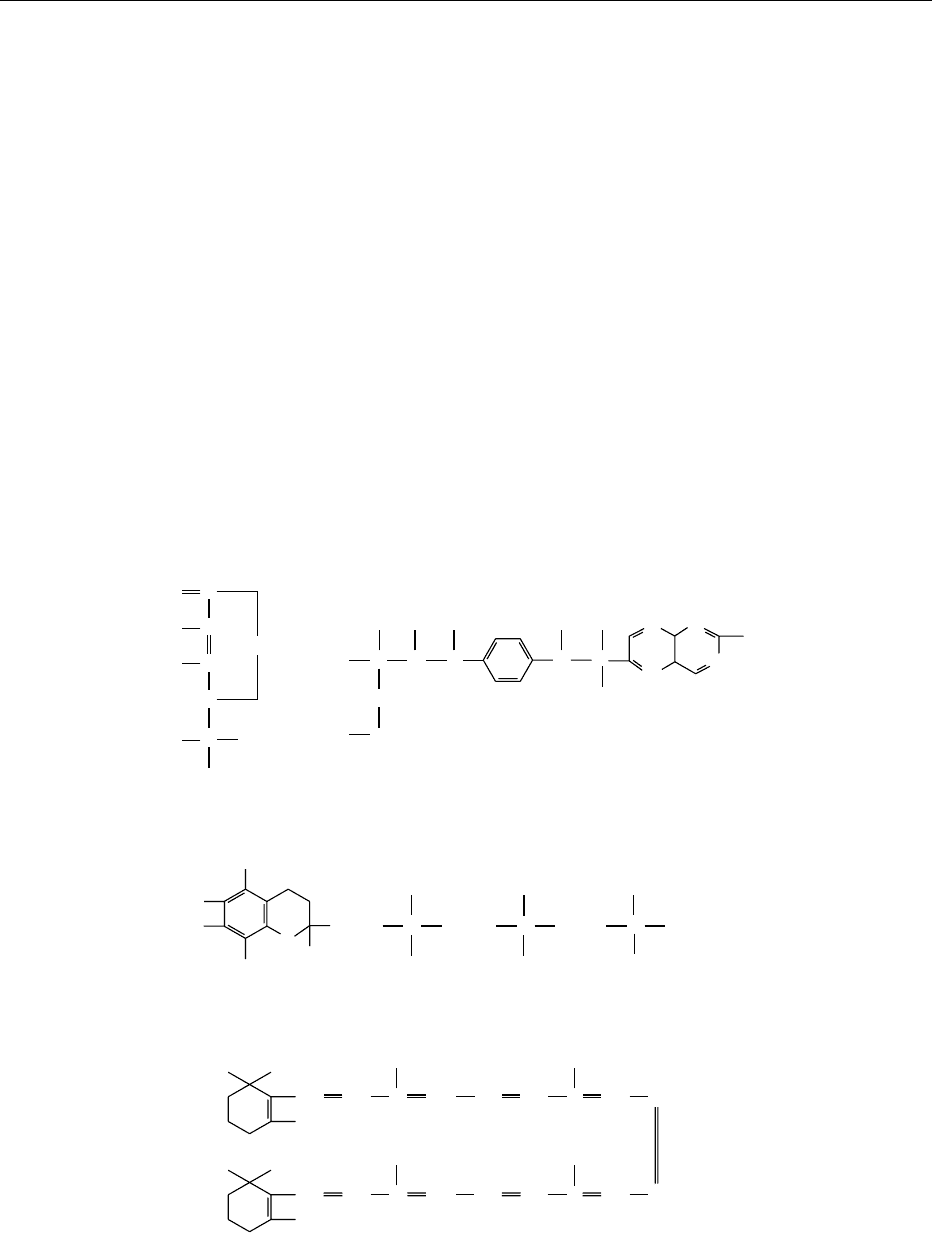

fig0003 Figure 3 Structures of common dietary antioxidant antimutagens.

4066 MUTAGENS

remain underrepresented in mutagenesis studies rela-

tive to synthetic chemicals. Additional characteriza-

tion is needed of the human consequences of exposure

to many antioxidants that appear to inhibit mutagen-

esis at low concentrations but have the opposite effect

at high concentrations. Finally, more emphasis should

be placed on the effects of chemical mixtures to study

the effects of combinations of compounds encoun-

tered in the diet.

See also: Aflatoxins; Amines; Carcinogens:

Carcinogenicity Tests; Food Additives: Safety;

Mycotoxins: Classifications; Occurrence and

Determination; Toxicology; Polycyclic Aromatic

Hydrocarbons; Saccharin

Further Reading

Ames BN (1998) Micronutrients prevent cancer and delay

aging. Toxicology Letters 102–103: 5–18.

Clayson DB (2001) Toxicological Carcinogenesis. Boca

Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers.

Franks LM and Teich NM (eds) (1997) Introduction to the

Cellular and Molecular Biology of Cancer, 3rd edn.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Friedberg EC, Walker GC and Siede W (1995) DNA Repair

and Mutagenesis. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

Hui YH, Kitts D and Stanfield PS (2001) Foodborne

Disease Handbook, Seafood and Environmental Toxins,

2nd edn., vol. 4. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Hui YH, Smith RA and Spoerke DG, Jr. (eds) (2001) Food-

borne Disease Handbook, Plant Toxicants, 2nd edn, vol.

3, New York: Marcel Dekker.

Kilbey BJ, Legator M, Nichols W and Ramel C (1984)

Handbook of Mutagenicity Test Procedures. Amster-

dam: Elsevier Science.

Kitchin KT (ed.) (1999) Carcinogenicity: Testing, Predict-

ing, and Interpreting Chemical Effects. New York:

Marcel Dekker.

Klug WS and Cummings MR (2000) Concepts of Genetics,

6th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McKinnell RG, Parchment RE, Perantoni AO and Pierce

GB (1998) The Biological Basis of Cancer. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

National Research Council Monograph (1996) Carcino-

gens and Anticarcinogens in the Human Diet. Washing-

ton, DC: National Academy Press.

Pariza MW, Aeschbacher H-U, Felton JS and Sato S (eds)

(1990) Mutagens and carcinogens in the diet. In: Pro-

gress in Clinical and Biological Research, vol. 347. New

York: Wiley-Liss.

Pfeifer GP (ed.) (1996) Technologies for Detection of DNA

Damage and Mutations. New York: Plenum Press.

Twyman RM (1998) Advanced Molecular Biology: A

Concise Reference. Oxford: Bios Scientific.

Mutton See Sheep: Meat; Milk

MYCOBACTERIA

C H Collins and J M Grange, National Heart and Lung

Institute, London, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 The genus Mycobacterium contains over 60 species;

these are divided into rapid-growers, slow-growers,

and the human leprosy bacillus which has not been

convincingly cultivated in vitro. A few of the species

are obligate parasites, but most of them are environ-

mental saprophytes. The latter are widely distributed

in nature and have been isolated from natural waters,

wet soil, mud, compost, grasses, vegetables, unpas-

teurized milk, and butter. They have also been isol-

ated from domestic water pipes from which they

readily enter drinking water. Mycobacteria are char-

acterized by the possession of very thick, waxy, lipid-

rich hydrophobic cell walls. Being hydrophobic, they

tend to grow as fungus-like pellicles on liquid culture

media: hence the name Mycobacterium –‘fungus

bacterium.’

0002Even the rapidly growing mycobacteria grow

slowly in comparison with most other bacteria.

Mycobacteria may play a role in the decomposition

of organic material, particularly in sphagnum

MYCOBACTERIA

4067

marshes, but there are no reports of mycobacteria

causing spoilage in foods. They do not produce

appreciable amounts of toxic substances and do not

cause food poisoning. Pathogenic strains owe their

virulence to their ability to resist immune defense

mechanisms; they cause chronic infections.

0003 The obligate parasites are Mycobacterium tubercu-

losis (the human tubercle bacillus), M. bovis (the

bovine tubercle bacillus), and M. africanum (a species

first described in equatorial Africa and having rather

variable properties that are intermediate between the

other two). Variants of these species are occasionally

encountered and include M. microti (the vole tubercle

bacillus) and biochemically and genetically distinct

isolates from goats termed the caprine genotype or

M. tuberculosis subsp. caprae. All these species, often

grouped as the tuberculosis complex, are very closely

related and should be regarded as variants of a single

species. Other pathogens thought to be obligate para-

sites are M. leprae (the causative organism of lep-

rosy), M. paratuberculosis (the cause of Johne’s

disease or hypertrophic enteritis in cattle and other

ruminants) and M. lepraemurium (the cause of rat

leprosy). As M. leprae is uncultivable and other two

are very difficult to cultivate in vitro, the possibility

that they can replicate in the inanimate environment

cannot be excluded.

0004 Some of the saprophytic species occasionally cause

opportunistic infections of animals and humans. The

principal opportunist species are M. avium,

M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. kansasii,

M. xenopi, M. malmoense, and the rapidly growing

species M. chelonae and M. fortuitum. The first two

species are closely related and are often grouped to-

gether as the M. avium complex (MAC). Although

essentially saprophytic, MAC are the most patho-

genic of the opportunist mycobacteria. Members of

this complex are a common cause of tuberculosis in

birds and they also cause limited lesions, particularly

cervical lymphadenopathy, in mammals, including

pigs, cattle, and deer. Closely related to the MAC

are M. lepraemurium, M. paratuberculosis and the

wood pigeon bacillus (M. avium subsp. sylvaticum)

which resembles M. paratuberculosis in requiring

mycobactin, an iron-binding lipid extracted from

mycobacterial cell walls, for its in vitro cultivation.

A few other nutritionally very fastidious mycobac-

teria, requiring enriched media for their cultivation,

have recently been described. These include

M. genavense, which was originally detected in ac-

quired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients

by means of DNA amplification techniques. This

species has also been isolated from pet birds and a

dog and infected pets may thus pose a health hazard

to severely immunosuppressed persons.

Mycobacterial Disease

0005Although the human mycobacterial diseases differ

enormously in their clinical features they have certain

characteristics in common. They all commence with a

local lesion, which may or may not be clinically

evident, at the site of implantation of the causative

organism. They may be in the lung in the case of

inhaled bacilli, in the skin following trauma, or in

the pharynx or intestinal tract following ingestion of

the bacilli in contaminated food or water. In some

cases, notably in tuberculosis, the local lymph nodes

are also involved in the primary infection and the

lymphatic lesion may be much more extensive than

that at the site of implantation. Thus, ingestion of

milk contaminated with M. bovis often leads to a

cryptic tonsillar or pharyngeal lesion and gross en-

largement of one or more of the lymph nodes in the

neck – a condition known as scrofula. Bacilli may

enter the blood stream from the primary lesion and

then cause serious forms of primary tuberculosis,

notably tuberculous meningitis and disease of the

kidneys, bones, and joints. Thus, in countries where

there is (or was) a high incidence of human tubercu-

losis of bovine origin, scrofula and associated non-

pulmonary manifestations of the disease are (or were)

commonly seen in children.

0006Unless one of the serious sequelae of primary

tuberculosis develops, the primary complex usually

resolves, but the disease reactivates in about 5% of

infected persons to cause postprimary tuberculosis,

years or even decades later. (The risk of reactivation

is much higher in immunosuppressed persons and

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has

emerged as the most prevalent predisposing factor

for the development of tuberculosis worldwide. A

person dually infected by HIV and M. tuberculosis

has a 8–10% chance of developing active tuberculosis

annually.) Cases of tuberculosis due to late reactiva-

tion of M. bovis infection still therefore occur in

countries that have virtually eradicated tuberculosis

from cattle. In Europe and Australia, M. bovis

accounts for around 1% of cases of tuberculosis.

0007The way in which residual mycobacteria persist in

tissues for long periods is unknown. The reactivation

may occur at the site of the primary lesion (such as

cervical lymph nodes in the case of tuberculosis of

bovine origin), but more often it reactivates, for un-

known reasons, in the upper lobes of the lung. This

leads to open or infectious tuberculosis and there

have been reports of cattle being infected by such

patients. Also, and for unknown reasons, some cases

(about 25%) of postprimary human tuberculosis due

to M. bovis in Europe involve the genitourinary tract.

This rather insidious form of tuberculosis often passes

4068

MYCOBACTERIA

undiagnosed for long periods and farm workers with

this condition are known to have transmitted tuber-

culosis to cattle by urinating in cowsheds.

0008 In humans, some environmental mycobacteria are

able to cause lymphadenopathy, particularly in young

children; skin lesions following injections of contam-

inated material, superficial or penetrating injuries,

and surgery involving implantation of contaminated

prostheses such as porcine heart valves; pulmonary

disease, particularly in patients with pneumoconiosis

or other predisposing lung diseases; and disseminated

disease. The last, once rare, is now a common AIDS-

related condition and, for unknown reasons, is usu-

ally caused by the MAC, although some cases are due

to the more recently described M. genavense, referred

to above.

0009 In recent years there has also been speculation that

ingested mycobacteria, possibly from milk, might be

responsible for Crohn’s disease, a granulomatous

disease of the human intestine. Normal forms and

spheroplasts of mycobacteria have been isolated

from tissue excised from a few patients with Crohn’s

disease and DNA supposedly specific for M. para-

tuberculosis, the cause of Johne’s disease in cattle,

has been detected by the polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) in biopsies from patients with Crohn’s disease.

In some studies such DNA was detected in the major-

ity of specimens but in other studies no such DNA

was detected. These conflicting findings may be at-

tributable to methodological problems and techno-

logical advances may resolve the issue but at present

no firm conclusions can be drawn. Likewise, attempts

to detect antibodies to M. paratuberculosis in serum

and antigen in tissues, as well as trials of antimyco-

bacterial drugs, have yielded unconvincing results.

Sources of Infection

0010 The human tubercle bacillus, M. tuberculosis,isusu-

ally spread from person to person via expectorated

aerosols and causes pulmonary tuberculosis. Individ-

uals with open tuberculosis who work in the food

industry may therefore transmit the organisms to

other people and could possibly, in theory, contamin-

ate food. The bovine bacillus, M. bovis, causes pul-

monary tuberculosis in farm workers who inhale the

bacilli in aerosols expectorated by diseased cattle

while town dwellers usually become infected by

drinking contaminated milk and predominantly

develop nonpulmonary tuberculosis.

0011 Although persons working with other animals with

disease due to M. bovis, including seals, elk, and a

rhinoceros with tuberculous rhinitis, have become

tuberculin-positive, overt disease has seldom been

reported. A few strains of the caprine genotype

have, however, been isolated from humans with

tuberculosis, including one isolate from a veterinary

surgeon with a recent history of working with tuber-

culous goats, and a seal trainer contracted tubercu-

losis due to an M. bovis-like strain from a captive seal

in Australia.

0012Mycobacterial disease may result from the inocu-

lation of the bacilli into the skin. In areas where

tuberculosis of cattle is common, food handlers

are at risk of developing tuberculous lesions of the

hands as a result of contamination of minor cuts and

abrasions, the resulting condition being known as

butcher’s wart (it is also known as prosector’s wart,

as anatomists and pathologists were likewise exposed

to this occupational hazard).

0013Food and drink may serve as vectors for the trans-

mission of pathogenic mycobacteria. By far the most

likely vehicle, leading to disease of the alimentary

tract, is unpasteurized milk. Meat and water are

also possible sources, but are much less important.

(See Milk: Processing of Liquid Milk.)

Unpasteurized Milk

0014There is a long history of human infection resulting

from the consumption of milk that contained

M. bovis. In developed countries such as the UK

these infections are now rare for two reasons: the

eradication of tuberculosis among cattle by tubercu-

lin testing and slaughter; and the pasteurization of

milk for human consumption. Both have been the

subject of legislation. Milk-borne tuberculosis is still

a hazard, however, in developing countries.

0015The history of milk-borne tuberculosis in the UK

illustrates this. The disease in cattle (and other

animals) had been recognized as an economic prob-

lem for centuries. By the turn of the century it was

known that tuberculosis in cattle was caused by

M. bovis, but Robert Koch, who had discovered the

tubercle bacillus in 1882 and was regarded as a world

authority on the subject, told the British Congress on

Tuberculosis in 1901 that the bovine organism did

not cause the disease in humans and that measures

to counteract infection with that organism were

unnecessary. This was disputed by certain British

bacteriologists and veterinarians and it was not

until after the publications of the findings of a Royal

Commission in 1911 that the bovine bacillus was

accepted as the causative organism of many cases of

nonpulmonary tuberculosis, notably cervical lymph-

adenopathy, abdominal and skeletal tuberculosis,

particularly in children.

0016Official action was slow, however, and in the 1930s

it was known that about 40% of all cattle slaughtered

in public abattoirs had tuberculous lesions and that

about 0.5% of all dairy cows produced milk that

MYCOBACTERIA

4069

contained the bovine tubercle bacillus. The eradica-

tion scheme that followed was initially voluntary and

did not become compulsory until after World War II.

By 1960 all dairy herds in the UK had been tested and

by 1979 the reactor rate had fallen dramatically and

only 0.18% of herds were infected. This may well

represent an irreducible minimum, because reinfec-

tion, from humans and other animals (e.g., badgers)

may still occur and therefore there is still a risk of

infection from unpasteurized milk although, at pre-

sent, as a result of more legislation, very little of this is

sold for immediate consumption in this country.

0017 Goats may also be infected, and tubercle bacilli

have been recovered from their milk. The consump-

tion of raw goats’ milk is therefore not without risk.

0018 Little is known about the role of milk in other

mycobacterial infections. The possible link between

milk-borne M. paratuberculosis and Crohn’s disease

has been referred to above. Members of the MAC and

other saprophytic mycobacteria have been isolated

from milk, but no direct link has been established

between the presence of these organisms in milk and

human disease, although contaminated milk is a

possible source of M. avium causing disease in AIDS

patients. Although DNA specific for M. avium, in-

cluding the sylvaticum subspecies, has been detected

in a few biopsies from patients with Crohn’s disease,

their role as primary pathogens remains, as in the case

of M. paratuberculosis, highly speculative.

Meat

0019 In most parts of the world meat is cooked before it is

eaten, but there is nevertheless the possibility that

there is insufficient heat penetration and that tubercle

bacilli may remain viable in parts of the meat. Cross-

contamination from infected meat to food ready for

consumption is also a possibility. As indicated above,

some infected cattle still reach slaughterhouses and

the meat of some may be tuberculous. Five cases of

tuberculosis due to M. bovis occurred over a 2-year

period in abattoir workers in South Australia: four of

the five cases involved the lung, suggesting that infec-

tion followed inhalation of aerosols. In addition, a

DNA fingerprinting study of strains of M. bovis

isolated from patients in Australia between 1970

and 1994 revealed that the majority of Australian-

born patients had worked in the meat and livestock

industries and had disease due to strains similar to

those found in Australian cattle.

0020 The incidence of tuberculosis among sheep is low,

as it is among pigs, although members of the MAC

have been responsible for outbreaks and single cases

of tuberculous disease in piggeries. Bovine tubercle

bacilli have been isolated from rabbits, wild and

farmed, and along with the avian bacillus, from a

variety of poultry. In the UK and New Zealand

farmed, but not wild, deer are now known to suffer

from tuberculosis. In the Middle East and India there

is evidence that some of the camels that are slaugh-

tered for their meat are tuberculous.

0021Fortunately, in developed countries, the systems of

meat inspection, required by law, prevent the sale for

human consumption of bovine, ovine, and porcine

carcasses, or parts of them, that may be infected.

There is still a trade, however, in carcasses, e.g., of

goats, pigs, rabbits, and poultry, that escapes an

official inspection and as yet in the UK carcasses of

farmed deer are exempt from official inspection. All

these animals offer a degree of hazard to the food

handler and the consumer.

0022Fish are not normally a source of mycobacterial

disease, although there have been a few cases of

disease due to M. marinum infection, manifesting as

warty skin lesions, in fishermen and fishmongers,

presumably as a result of infection of dermal abra-

sions. Multiple regression analysis has shown that

regular consumption of raw or partly cooked fish

and shellfish is associated with an increased risk of

disseminated disease due to the MAC in AIDS

patients.

Water

0023Several species of mycobacteria, some of which are

opportunist pathogens, have been isolated from piped,

bottled, and natural waters. Tubercle bacilli, however,

have never been recovered from water supplies.

0024There is adequate evidence that infections due to

some opportunist mycobacteria result from the inhal-

ation of aerosols containing the organisms. In the

great majority of cases ingestion of these species

does no harm (overt abdominal infection associated

with them is extremely rare), but they may temporar-

ily colonize the alimentary and upper respiratory

tracts. There is evidence that they may cross the epi-

thelial barrier (translocation) and persist for some

time in the draining lymph nodes: thus they have

been isolated from excised tonsils and abdominal

lymph nodes. Water has been postulated as a source

of infection in AIDS patients with disseminated

mycobacterial disease due to the M. avium, although

epidemiological evidence is conflicting, but M. gene-

vense was detected in tap water at a hospital with an

unusually high incidence of HIV-related disseminated

disease due to this species.

Isolation of Mycobacteria from Milk, Meat,

and Water

0025Tubercle bacilli and other pathogenic mycobacteria

are in Hazard Group 3 of the Advisory Committee on

4070

MYCOBACTERIA

Dangerous Pathogens and other similar authorities.

Such organisms may be dispersed as aerosols during

laboratory manipulations, and individuals who inhale

them may become infected. Any bacteriological pro-

cedure involving them or material that may contain

them must be carried out under Containment Level 3

conditions in microbiological safety cabinets.

0026 In some parts of the world the conventional tech-

niques for isolating mycobacteria on solid media are

being replaced by more rapid radiometric methods

and more recent nonradiometric automated systems

and also by the PCR and its derivatives. Originally

evaluated in the field of human disease, they are

increasingly being applied to veterinary microbiology,

food hygiene, and environmental work. There

have, for example, been reports of the use of PCR

to detect and identify waterborne mycobacteria,

M. paratuberculosis in pasteurized milk, and M. bovis

in tissues obtained postmortem from various animals.

Likewise, DNA fingerprinting techniques suitable for

epidemiological studies on M. bovis from animal and

human sources are now available.

0027 The traditional methods for the isolation of myco-

bacteria are described below, but the final identifica-

tion of tubercle bacilli and other mycobacteria is too

detailed to be included. Alternatively, cultures of

suspected mycobacteria may be sent to a reference

laboratory, a regional tuberculosis laboratory, or a

veterinary laboratory. For information on automated

systems and nucleic acid-based technology, the rap-

idly changing primary literature should be consulted.

Milk

0028 Direct microscopic examination of milk for acid-fast

bacilli is unrewarding as saprophytic mycobacteria

are often present, as are artifacts that retain the

fuchsin stain.

0029 A suitable method for recovering tubercle bacilli

(and other mycobacteria) from the milk of individual

cows or from small groups of cows is given below.

0030 Centrifuge at least 50 ml of the milk at 3000 rpm

for 20 min. Remove the cream to a small tube, add

4 ml of 4% sodium hydroxide and stand for 15 min;

add 6 ml of 14% monopotassium phosphate contain-

ing phenol red indicator to indicate neutralization;

centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 15 min; discard super-

natant fluid and culture the deposit.

0031 Discard the remaining supernatant fluid from the

original centrifugation and add 2 ml of 4% sodium

hydroxide to the deposit and stand for 15 min; add

3 ml of 14% monopotassium phosphate (3 ml) and

proceed as above.

0032 Divide the deposits between several tubes of

Lo

¨

wenstein–Jensen medium or Middlebrook medium

containing antibiotics. Incubate at 37

C for 6–8

weeks. Check the identity of any organisms that

grow by Gram and Ziehl–Neelsen stains.

0033Identify acid-fast bacilli by the methods described

in standard textbooks or send cultures to a specialist

laboratory.

Meat

0034For full details, the World Health Organization

guidelines for speciation within the Mycobacterium

tuberculosis complex should be consulted. The

recommended methods are briefly summarized here.

0035The material should be selected by a veterinarian or

meat inspector familiar with the macroscopic appear-

ance of tuberculous lesions. The usual specimens are

lymph nodes from the respiratory and gastrointest-

inal tracts, lung, and liver tissue and these should be

placed in wide-mouthed, hermetically sealed plastic

or glass pots.

0036Cut about 10 g of the sample into small pieces with

sterile instruments and further homogenize the pieces

in a Griffith tube or mechanical blender.

0037Remove about 3 ml of homogenized tissue with a

wide-bore pipette and add to an equal quantity of

autoclaved 4% sodium hydroxide in a screw-capped

tube, mix well and stand for 15–20 min, with occa-

sional shaking.

0038Neutralize with a 14% w/v solution of monopotas-

sium phosphate containing phenol red indicator

(about 40 mg l

1

) and allow to stand until the indica-

tor turns red, indicating that neutralization is com-

plete. Centrifuge fluid at 3000 rpm for 20 min, decant

the supernatant fluid, and inoculate the deposit on

two slopes of Lo

¨

wenstein–Jensen media and two

slopes of a related medium, such as Stonebrink’s

medium, that contains sodium pyruvate instead of

glycerol and which favors the growth of M. bovis.

0039Incubate slopes at 35–37

C for up to 8 weeks. Read

weekly, examine colonies for acid-fastness, and

arrange for identification by a specialist laboratory.

Water

0040The sample should consist of at least 1 l of water and

be delivered to the laboratory as soon as possible.

0041Pass separate 100-ml volumes of the whole sample

through membrane filters. Place the membrane filters

in 4% sodium hydroxide solution for 5 min (e.g., in a

Petri dish), then in 14% monopotassium phosphate

solution containing phenol red for several minutes.

0042Cut the membranes into strips 5 mm wide and

place each strip on the surface of Lo

¨

wenstein–Jensen

or Middlebrook antibiotic medium in screw-capped

tubes. Incubate at 35–37

C. Examine every few days

as some mycobacteria grow rapidly.

0043Examine colonies for acid-fastness and arrange for

identification, if necessary.

MYCOBACTERIA

4071

0044 In developed countries, foodborne mycobacteria

do not offer a serious health hazard and routine

laboratory examinations are not justified. In special

circumstances attempts may be made to culture

the organisms by the methods described above.

However, the essential and expensive equipment

requirements for Containment Level 3 preclude iden-

tification in most laboratories. The advice and ser-

vices of reference and other specialized laboratories

should be sought.

See also: Milk: Processing of Liquid Milk

Further Reading

Collins CH and Grange JM (1983) A review: the bovine

tubercle bacillus. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 55:

13–29.

Collins CH and Grange JM (1987) Zoonotic implications

of Mycobacterium bovis infections. Irish Veterinary

Journal 41: 363–366.

Collins CH, Grange JM and Yates MD (1984) A review:

mycobacteria in water. Journal of Applied Bacteriology

57: 193–211.

Collins CH, Lyne PM and Grange JM (eds) (1995) Collins

and Lyne’s Microbiological Methods, 7th edn. Oxford:

Butterworth Heinemann.

Collins CH, Grange JM and Yates MD (1997) Tuberculosis

Bacteriology Organization and Practice, 2nd edn.

Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

Cosivi O, Grange JM, Daborn CJ et al. (1998) Zoonotic

tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in developing

countries. Emerging Infectious Diseases 4: 59–70.

Cousins DV and Dawson DJ (1999) Tuberculosis due to

Mycobacterium bovis in the Australian population:

cases recorded during 1970–1994. International Journal

of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 3: 715–721.

Cousins DV, Williams SN and Dawson DJ (1999) Tubercu-

losis due to Mycobacterium bovis in the Australian

population: DNA typing of isolates, 1970–1994. Inter-

national Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 3:

722–731.

Covert TC, Rodgers MR, Reyes AL and Stelma GN (1999)

Occurrence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in environ-

mental samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiol-

ogy 65: 2492–2496.

Fordham von Reyn C, Arbeit RD, Tosteson AN et al. (1996)

The international epidemiology of disseminated Myco-

bacterium avium complex infection in AIDS. Inter-

national MAC Study Group. AIDS 10: 1025–1032.

Grange JM and Collins CH (1987) Bovine tubercle bacilli

and disease in animals and man. Epidemiology and

Infection 92: 221–234.

Grange JM, Yates MD and de Kantor IN (1996) Guidelines

for Speciation within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis

complex, 2nd edn. WHO/EMC/ZOO/96.4. Geneva:

World Health Organization.

Hubbard J and Surawicz CM (1999) Etiological role of

Mycobacterium in Crohn’s disease: an assessment of

the literature. Digestive Diseases 17: 6–13.

Millar D, Ford J, Sanderson J et al. (1996) IS900 PCR to detect

Mycobacterium paratuberculosis in retail supplies of whole

pasteurized cows’ milk in England and Wales. Applied and

Environmental Microbiology 62: 3446–3452.

Moda G, Daborn CJ, Grange JM and Cosivi O (1996) The

zoonotic importance of Mycobacterium bovis. Tubercle

and Lung Disease 77: 103–108.

O’Reilly LM and Daborn CJ (1995) The epidemiology of

Mycobacterium bovis infections in animals and man: a

review. Tubercle and Lung Disease 76: 1–46.

Roberts TA (1986) A retrospective assessment of human

health protection benefits from removal of tuberculous

beef. Journal of Food Protection 49: 293–298.

Robinson P, Morris D and Antic R (1988) Mycobacterium

bovis as an ocupational hazard in abattoir workers. Aus-

tralia and New Zealand Journal of Medicine 18: 701–703.

Thoen CO and Steele JH (eds) (1995) Mycobacterium bovis

Infection in Humans and Animals. Ames, Iowa: Iowa

State University Press.

Wards BJ, Collins DM and de Lisle GW (1995) Detection of

Mycobacterium bovis in tissues by polymerase chain

reaction. Veterinary Microbiology 43: 227–240.

Van Kruiningen HJ (1999) Lack of support for a common

etiology in Johne’s disease of animals and Crohn’sdisease

in humans. Inflammatory Bowel Disease 5: 183–191.

MYCOPROTEIN

M J Sadler, MJSR Associates, Ashford, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Myco-protein is produced from microfungi, aerobic

organisms that live in the soil and convert

carbohydrate to protein. Research to produce food

from microfungi began in the early 1960s. This was at

a time when many projects were being set up to

develop single-cell protein sources suitable for animal

and human consumption in response to the predicted

protein gap in developing countries. There are reports

of three products produced form microfungi, but by

far the most successful myco-protein product is sold

under the trade name ‘Quorn

TM

.’

4072 MYCOPROTEIN

0002 Myco-protein is the generic name of the major

raw material used in the manufacture of Quorn

TM

products. It comprises the RNA-reduced biomass

composed of the hyphae (cells) of the organism

Fusarium venenatum A3/5 (deposited with the

ATCC as PTA-2684) grown under axenic conditions

in a continuous fermentation process. Quorn

TM

is

the brand name of a range of meat-alternative

products made from myco-protein. Quorn

TM

products

include pieces and mince for use in home cooking

in addition to a range of convenience products

such as burgers, fillets, goujons, nuggets, and ready

meals.

0003 Quorn

TM

myco-protein is the first truly ‘new’ food

product developed for humans. Introduced to the UK

food market in 1984, Quorn

TM

products are the result

of a development program, designed to produce

single-cell protein, that was started in the 1960s. In

addition to availability in all major UK and Irish food

retailers, Quorn

TM

products are now available in an

increasing number of retailers within Continental

Europe, including Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland,

Sweden, Switzerland and France, and in the USA.

0004 This article covers the cultivation and harvesting

of myco-protein, and its properties including accept-

ability, safety, and nutritional value. Known and

other potential functional health effects of consuming

myco-protein are also discussed.

0005 It was predicted in the late 1950s that within three

decades, there would be a shortage of protein across

the world – the so-called ‘protein gap.’ In response to

this, many projects were set up in the early 1960s to

develop feeds or foods from single-cell protein

sources that would be suitable for animal or human

consumption.

0006 Ranks Hovis McDougall (RHM) Research Centre

in the UK undertook one such project, which started

in 1964. The original aims were to convert starch

into a protein-rich food that was highly nutritious,

delicious, and safe to eat. The project focused on the

potential of microfungi to produce a high-protein

food (myco-protein). This resulted two decades later

in the successful development of the Quorn

TM

(a regis-

tered trade mark of Marlow Foods Ltd, UK) range of

products, which have been marketed as a human food

for the past two decades.

0007 It should be noted that the commercial deve-

lopment of myco-protein was a joint venture

between RHM and ICI (Marlow Foods). In 1990,

ICI assumed full control of the business. However,

in 1993, ICI de-merged into ICI and Zeneca, and

Marlow Foods became part of Zeneca. In 1998,

Zeneca merged with Astra (Sweden) to become

AstraZeneca.

Production

Cultivation

0008Cultivation of fungal mycelia has many factors in

common with the production of yeast and bacteria,

although because fungi are multicellular or coenzo-

cytic, the term ‘single-cell protein’ cannot strictly be

used to describe fungi produced by fermentation. The

advantages of microfungi are that they can utilize a

wide range of substrates, they have straightforward

nutritional requirements, and they are relatively easy

to harvest from culture broths on account of their

particle size.

0009In addition, the whole microfungi can be consumed

without any reported problems of toxicity and with

only a very low level of adverse reactions. Fungal

mycelia have a high nutritional value, desirable tex-

ture, and mild smell and flavour. Acceptability is less

of a problem than for food from other lower organ-

isms, since fungi already play a role in the human diet.

0010The microfungi Fusarium venenatum A3/5 (de-

posited with the ATCC as PTA-2684) was chosen by

RHM for the production of the new myco-protein

product, on account of its suitable organoleptic and

nutritional properties.

0011Growth requirements and conditions Myco-protein

is grown in an airlift or pressure-cycle fermenter in a

liquid medium providing all the nutrients required for

growth. In preference to a batch culture, a continu-

ous-flow aerobic culture system is used in which the

culture medium is continuously fed to the fermenter

and the broth continuously drawn off for filtering

such that the volume of the fermenter is displaced

approximately every 5–6 h. This ensures that steady-

state conditions are maintained and that optimal

productivity is achieved. Optimizing the process con-

ditions improves the yield, quality, and uniformity of

the end product, and the efficiency of the process. The

cell mass doubles every 4–5h.

0012The carbon substrate used is glucose syrup, which

is obtained from hydrolyzed corn. Ammonium is the

source of nitrogen, and is also used to regulate the

pH, which is maintained between 4.5 and 7.0. Salts of

potassium, manganese, cobalt, calcium, magnesium,

iron, copper, and biotin are supplied as a liquid feed-

stock from tanks adjacent to the fermenter. Com-

pressed air is the source of oxygen, and its injection

into the fermenter keeps the broth in continuous

motion. All the ingredients of the culture medium

are sterile and of food- or reagent quality. The tem-

perature of the broth is maintained at 30

C, and it is

therefore necessary to cool the fermenter.

MYCOPROTEIN 4073