Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MANAGING RESOURCES: PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 331

or group representatives, and performed tasks that had previously been done by foremen

and industrial engineers. The Swedish model was, however, less uniform and fixed. It rep-

resented a social compromise between different interests: between management’s interest

in delegating tasks and responsibility without yielding control and the trade union’s

aspirations to achieve a genuine shift in the balance of power. The degree of the work

teams’ autonomy and decision-making power varied according to the state of production,

the managerial policy, the labour situation and other factors affecting the local balance of

forces.

Third, the role of first-line management was changed from that of having direct

control to coordinating, planning and supporting. At those Japanese ‘transplants’

Source: Berggren (1992: 9).

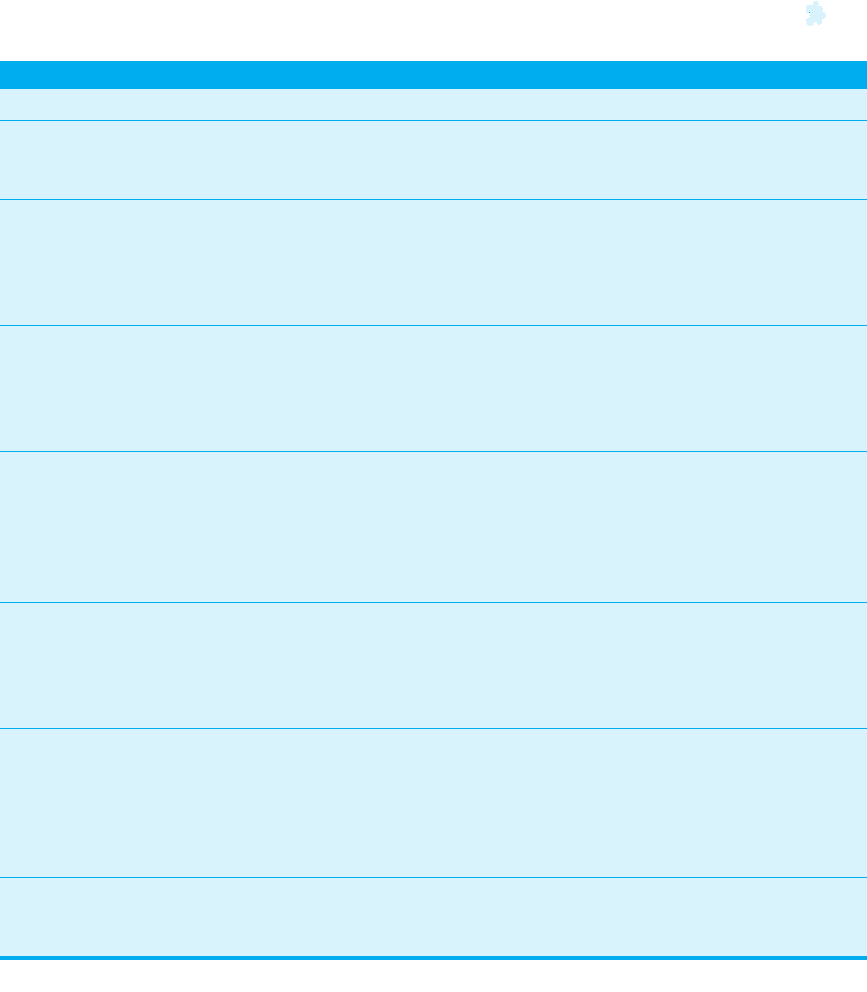

Table 7.2 The Japanese and Swedish models of teamwork

Characteristic Japanese Swedish

Production arrangement Trimmed lines with JIT control Socio-technical adaptation and

increased work content, most

radically in complete assembly

Relationship between groups Elimination of all buffers and

variation in individual work pace

Reduction of group

interdependencies by increasing

worker autonomy and allowing

variations in individual work

pace

Supervision and coordination Dense structure and

strengthened role vis-à-vis both

staff and subordinates; foremen

decide matters concerning

training, promotion and wages

Reduced control (how much is a

contested issue); tasks shifted

towards planning, and daily

responsibility is delegated to the

teams

Administrative control Team leader is selected by first-

line management; suggestions

by the workers encouraged but

decisions are taken

hierarchically to ensure

standardization

Group leader/representative

chosen by the team; the post is

often rotated, but this is a

controversial question

Work intensity and performance

demands

Intense managerial and peer

pressure for maximum

performance; no upper

performance limits

Performance limits are specified

in contract between company

and union; actual work intensity

varies, depending on wage

system and peer pressure

Union role Work organization, production

pace and job design defined

exclusively by company

Job content, wage system and

prerogatives regulated by

contract; unions engaged in

questions of plant

management’s structure and

staffing

Clear structure of interests

Team closely tied to plant

management

Autonomy – a social compromise

Work organization expresses

partly opposed interests

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 331

investigated, in contrast, teamwork usually went hand in hand with a strengthening of

the managerial structure. In many cases – for example, Nissan in the UK or Toyota in

Kentucky, USA – the team was organized directly around the foreman. These forms of

teamwork entailed a reduction of worker autonomy and an increase in managerial

control. In Japan, teams were organized around a team leader rather than a foreman, and

the team leader would carry out assembly tasks as well as coordinate the team, and, in

particular, would fill in for any absent worker. Similar to the situation in the transplants,

however, the team leader decided on matters regarding wages, promotion, and so on, and

control led the team members.

Fourth, in Sweden, the Metal Workers’ Union strongly committed itself, both cen-

trally and locally, to the development of this new organizational form. It was especially

interested in strengthening the teams’ decision-making prerogatives, as well as their

prospects for developing collective competence.

The Uddevalla factory closed in 1993, hit by a decline in Volvo sales and a conse-

quent contraction of production capacity. This does not imply, however, that the

production principles it sought to develop were inferior. Moreover, the factory’s reopening

in 1996, following its conversion to produce sport and luxury models, suggests that this

technological trajectory has not yet fulfilled its true potential. It has been suggested that

the Uddevalla experiment may not only provide an alternative to Toyotism but may also

surpass it, with its total abandonment of the assembly line, maximization of multiple

skills among the workforce as a function of cognitive abilities to memorize a set of

complex tasks, moderate level of automation, and close attention to the motivations and

expectations of operators (Boyer and Durand, 1997: 53–4). It is not surprising, then, that

by the end of the 1980s certain Japanese companies were envisaging the introduction of

programmes combining elements of the Scandinavian model with the traditional Toyotist

model.

7.3 Production Systems and the Societal

Environment

8

From the 1980s onwards, there has been wide acceptance of the argument that produc-

tion systems cannot operate in isolation from the rest of the society and, hence, cannot be

understood in isolation from their societal context. The emergence and stability of pro-

duction systems are seen as dependent on their compatibility with society-wide social

relations, such as industrial relations and skills formation, along with some forms of state

intervention. Clearly, the skills of workers have to be acquired either within schools and

training institutes or on the job within the firm. The pay system and the nature of the

hierarchy within the firm are influenced by the style of industrial relations and the strat-

ification of competencies at a society-wide level. Societal conceptions about fairness

necessarily interfere with the internal management and influence income differentials

across skill levels, firms or regions. Even the organization of capital markets must be con-

sidered. Some mass-production industries require such a vast amount of capital that the

very characteristics of financial intermediation play an important role in the viability of

332 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

8

Unless indicated otherwise, this section is based on Hollingsworth (1997).

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 332

any production system. Finally, the state delivers – or does not – some general precondi-

tions for productive efficiency to prosper: clear rules of the game concerning property

rights, but also labour law, international trade, access to knowledge, and so on. We could

call this complementarity between private management tools and their embeddedness

into more general, society-wide relationships a societal system of production.

A societal system of production is, then, a configuration of complex institutions

which include the internal structure of the firm along with the society’s industrial

relations, the training system, the relationships with competing firms, their suppliers and

distributors, the structure of capital markets, the nature of state intervention and the

conceptions of social justice (Boyer and Hollingsworth, 1997: 2). Given these comple-

mentarities at each period and for a given society, there exist a limited number of such

societal systems of production, since a coalescence of various institutional arrangements

assumes a mutual adjustment among a number of different institutions. And even if a

society may have more than one societal system of production, one generally imposes its

flavour, constraints and opportunities on other production systems. One may label such a

societal system of production, the dominant societal system of production. This is the one

that is tuned to the core societal institutions concerning labour, finance and state inter-

vention, and is more involved with an international regime. While there is considerable

variability in the way production is organized within a particular society, that variability

generally exists within the broad parameters of a single societal system of production

(Boyer and Hollingsworth, 1997).

The following discussion includes the institutional configurations of the societal

systems of mass and flexible production. Japanese lean production, German diversified

quality production and Swedish Uddevallaism are included as examples or variants of

flexible production. As indicated, the discussion also includes the institutional configura-

tion of the US societal system of production as an example of a powerful economy that

has, historically, been embedded in a societal system of mass standardized production,

and largely for that reason its economic actors find it very difficult to mimic the practices

and performance of their Japanese and German competitors. The latter analysis demon-

strates how a society’s societal system of production limits its capacity to compete in

certain industrial sectors, but enhances its competitiveness in others.

Mass standardized societal systems of production

As indicated, not just any country could have a mass standardized production system as

its dominant form of production. For such a social system to be dominant, firms have to be

embedded in a particular environment, one with a particular type of industrial relations

system, education system and financial markets, one in which the market mentality is very

pervasive, civil society is weakly developed, and the dominant institutional arrangements

for coordinating a society’s economy tend to be markets, corporate hierarchies and a

weakly structured regulatory state. As already suggested, firms that successfully employ a

mass-production strategy have to use specific types of machinery – that is, specific-purpose

machines – and relate in particular ways to other firms in the manufacturing process.

Firms engaged in mass standardized production require large, stable and relatively well-

defined markets for products that are essentially slow in their technological complexity

and relatively low in their rate of technological change (see Table 7.3).

MANAGING RESOURCES: PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 333

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 333

334 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

‘Because specific purpose machines operate in relatively stable markets, firms either

engaged in backward integration or were in a strategic position to force their suppliers to

invest in complementary supplies and equipment. Once firms announced their need for

specific types of parts, suppliers had to produce at very low costs or lose their business.

Over time, those firms that excelled in mass production tended to develop a hierarchical

system of management, to adopt strategies of deskilling their employees, to install single-

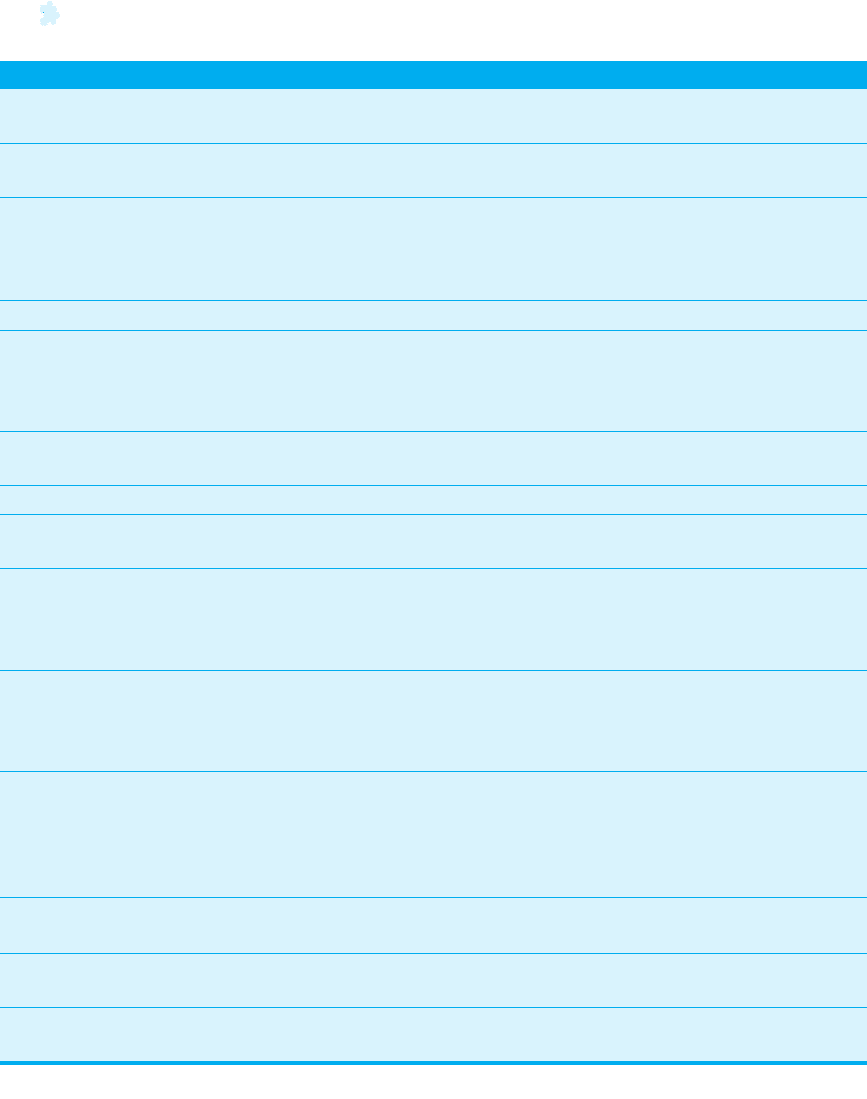

Table 7.3 A typology of societal systems of production

Variables Mass standardized

production

Flexible production

Work skills Narrowly defined and very

specific in nature

Well-trained, highly flexible and

broadly skilled workforce

Institutional training facilities Public education emphasizing

low level of skills

Greater likelihood of strong

apprenticeship programmes

linking vocational training and

firms

Investment in work skills by firm Low High

Labour–management relations Low trust between labour and

management; poor

communication and hierarchical

in nature

Relatively high degree of trust

Industrial relations Conflictual labour–management

relations

High social peace between

labour and management

Internal labour market Rigid Flexible

Work security Relatively poor security Long-term employment,

relatively high job security

Relationship with other firms Highly conflictual, rather

impoverished institutional

environment

Highly cooperative relationships

with suppliers, customers and

competitors in a very rich

institutional environment

Collective action Trade associations poorly

developed and where in

existence are lacking in power to

discipline members

Trade associations highly

developed with capacity to

govern industry and to discipline

members

Modes of capital formation Capital markets well developed;

equities are highly liquid

Capital markets are less well

developed, strong bank–firm

links, extensive cross-firm

ownership, long-term ownership

of equity

Anti-trust legislation Designed to weaken cartels and

various forms of collective action

More tolerance of various forms

of collective action

Type of civil society in which

firms are embedded

Weakly developed Highly developed

Degree of pervasiveness of

market mentality of society

High Low

Source: adapted from Hollingsworth (1997: 274–5).

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 334

purpose, highly specialized machinery, and to engage in arm’s-length dealings with sup-

pliers and distributors based primarily on price. In the long run, the more a firm produced

some standardized output, the more rigid the production process became – e.g. the more

difficult it was for the firm to produce anything that deviated from the programmed

capacity of its special purpose machines. On the other hand, such firms were extraordi-

narily flexible in dealing with the external labor market. As employees in firms engaged in

standardized production had relatively low levels of skill, one worker could easily be

exchanged for another. Management had little incentive to engage in long-term contracts

with their workers or to invest in the skills of their employees’ (Hollingsworth, 1997:

269).*

As mass production has been developed in the USA, it should come as no surprise

that historians found that US schools were historically integrated into a societal system of

mass standardized production and that the education system was vocationalized. ‘In such

a system, schools for most of the labor force tended to emphasize the qualities and person-

ality traits essential for performing semi-skilled tasks: punctuality, obedience, regular and

orderly work habits’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 270).* ‘Hogan argues that schools in a social

system of mass production provide skills that are less technical than social and are less

concerned with developing cognitive skills and judgments than attitudes and behavior

appropriate to mass production organizations and their labor process’ (Hollingsworth,

1997: 271).* ‘Because labor markets in such a system were segmented, however, edu-

cational systems also tended to be segmented, but intricately linked with one another.

Thus, such a system also had some schools for well-to-do children that emphasized

student participation and less direct supervision by teachers and administrators’

(Hollingsworth, 1997: 270).*

Where societal systems of mass standardized production have been highly institu-

tionalized, such as in the USA, the financial markets have also been highly developed.

‘Large firms in such a system – in comparison with those in other societies – have tended

to expand from retained earnings or to raise capital from the bond or equity markets, but

less frequently from bank loans.

‘Once financial markets become highly institutionalized, securities become increas-

ingly liquid. And the owners of such securities tend to sell their assets when they believe

their investments are not properly managed. Since management embedded in such a

system tends to be evaluated very much by the current price and earnings of the stocks

and bonds of their companies, it has a high incentive to maximize short-term consider-

ations at the expense of long-term strategy’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 271).* (See Chapter 6

for an extended explanation of this topic.)

‘This kind of emphasis on a short-term horizon limits the developments of long-term

stable relations between employers and employees – a prerequisite for a highly skilled and

broadly trained workforce. Instead, the short-term maximization of profits means that

firms in a societal system of mass standardized production tend to be quick to lay off

workers during an economic downturn, thus, being heavily dependent on a lowly and

narrowly skilled workforce’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 271).*

MANAGING RESOURCES: PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 335

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 335

336 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Societal systems of flexible production

Flexible production is the production of goods by means of general-purpose resources,

a system of production that can flexibly adapt to different market demands. ‘In systems in

which flexible production is dominant, there is an ever-changing range of goods with cus-

tomized designs to appeal to specialized tastes’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 272).* Similar to

what has just been argued for mass production, not all countries can have flexible produc-

tion as their dominant societal form of production. Moreover, because the institutional

arrangements of each social system of flexible production are system-specific, they are

not easily transferable from one society to another.

9

Societies with societal systems of flex-

ible production tend to have most, if not all, of the following characteristics, all of which

are mutually reinforcing (see also Table 7.3):

‘An industrial relations system that promotes continuous learning, broad skills,

workforce participation in production decision-making, and is perceived by

employees to be fair and just.

Less hierarchical and less compartmentalized arrangements within firms, thus

enhancing communication and flexibility.

A rigorous education and training system for labor and management, both within

and outside firms.

Well-developed institutional arrangements, which facilitate cooperation among

competitors.

Long-term stable relationships with high levels of communication and trust among

suppliers and customers.

A system of financing that permits firms to engage in long-term strategic planning’

(Hollingsworth, 1997: 277).*

In contrast to mass standardized production, flexible production requires workers

who have high levels of skills and who can make changes on their own. ‘This means that

there is much less work supervision than in firms engaged in mass production. Because of

the need to shift production strategies quickly, management in firms engaged in flexible

production must be able to depend on employees to assume initiative, to integrate concep-

tions of tasks with execution, and to make specific deductions from general directives. . . .

‘A key indicator to the development of a social system of flexible production in a

society is its industrial relations system. Highly institutionalized social systems of flexible

production require workers with broad levels of skills and some form of assurance that

they will not be dismissed from their jobs. Indeed, job security tends to be necessary for

employers to have sufficient incentives to make long-term investments in developing the

skills of their workers’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 272–3).*

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

9

Historically, however, there were always examples of flexible production in societies where a social system of

mass standardized production was dominant, and examples of standardized production occurred in societies in

which flexible production was most common.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 336

Moreover, firms engaged in flexible production methods tend to become somewhat

more specialized and less vertically integrated than those firms engaged in mass produc-

tion. As a result, such firms must be in close technical contact with other firms. ‘To be

most effective in employing technologies of flexible production, management must have a

willingness to cooperate and have trusting relationships with their competitors, suppliers,

customers, and workers. But the degree to which these trust relationships can exist

depends on the institutional environment in which firms are embedded. . . . But firms in

social systems of flexible production are embedded in environments with highly devel-

oped institutional forms of a collective nature which promote long-term cooperation

between labor and capital as well as between firms and suppliers. And the market men-

tality of the society is less pervasive. The collective nature of the environment also

facilitates cooperation among competitors’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 273).*

‘The economic importance of institutional arrangements for rich and long-term

relationships between labor and capital and among suppliers, customers, competitors,

governments, universities, and/or banks is that such arrangements link together econ-

omic actors having relatively high levels of trust with each other, and having different

knowledge bases – a form of coordination that is increasingly important as technology

and knowledge become very complex and change rapidly’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 273).*

For a societal system of flexible production to thrive, firms must be embedded in a com-

munity, region or country in which many other firms share the same and/or

complementary forms of production. Firms that adhere to the principles of a societal

system of production over long periods of time tend to do so either because of communi-

tarian obligations or because of some form of external coercion.

‘Moreover, for a social system of flexible production to sustain itself, firms must invest

in a variety of redundant capacities. Such redundancies are likely to result only if firms

are embedded in an environment in which associative organizations and/or the state

require such investments. Firms acting voluntarily and primarily from a sense of a highly

rational calculation of their investment needs are unlikely to develop such redundant

capacities over the longer run. Manufacturing firms engaged in flexible forms of produc-

tion require a workforce that is broadly and highly skilled, and capable of shifting from

one task to another and of constantly learning new skills. But firms that are excessively

rational in assessing their needs for skills are likely to proceed very cautiously in their skill

investments; in such firms, accountants and cost benefit analysts are likely to insist that

only those investments be made that will yield predictable rates of return. In a world of

rapidly changing technologies and product markets, firms that invest only in those skills

for which there is a demonstrated need are likely over time to have a less skilled workforce

than they need. . . . With knowledge and technology becoming more complex and

changing very rapidly, excessive rational economic thinking along the principles inherent

in a social system of mass production may well result in poor economic performance.

Thus, firms engaged in flexible production require excess or redundant investments in

work skills, and can sustain this over time only if they are embedded in a social system of

flexible production – which by definition has highly developed collective forms of behavior

MANAGING RESOURCES: PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 337

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 337

with the capacity to impose communitarian obligations among actors’ (Hollingsworth,

1997: 273–6)*

‘Another redundant investment – one that is somewhat complementary – involves

efforts to generate social peace. High quality and flexible production can persist only if

there is social peace between labor and management. The maintenance of peace is costly,

and it is impossible for cost analysts to demonstrate how much investment is needed in

order to maintain a high level of social peace. Thus, just as highly rational managers are

tempted to invest less in skills than will be needed over the longer term, so also they tend

to underinvest in those things that lead to social peace. But for a firm to have a sufficient

supply of social peace when needed, it must be willing to incur high investments in social

peace when it does not appear to need it. In this sense, investment in and cultivation of

social peace create a redundant resource which is exposed to the typical hazards of

excessive rationality and short-term opportunism’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 276).*

‘Investment in the redundant capacities of general skills and social peace tend to

require long-term employment relationships. And while firms may occasionally develop

such capacities based on voluntarily imposed decisions, such decisions tend to be less

stable and less effective for the development of broad and high level skills and social peace

than socially imposed or legally compulsory arrangements which originate from institu-

tionalized obligations. Social systems of mass standardized production represent a social

order based on contractual exchanges between utility-maximizing individuals, and most

firms in such systems underinvest in the skills of their workers and in social peace. Social

systems of flexible production require cooperative relations and communitarian obli-

gations among firms, as well as collective inputs that firms would not experience based

purely on a rational calculation of a firm’s short-term economic interests’

(Hollingsworth, 1997: 277).*

The societal system of lean production

As explained in the first section of this chapter, Japanese lean production involves a small-

batch flexible mass-production system and, hence, is based on flexible production

techniques. As a consequence, most of the societal features that support the development

of flexible production as the dominant societal system (mentioned in Table 7.3) also

support the development of lean production systems. One of the most important features

of the Japanese societal system of production, from which many have been derived and

which contributes to the development of flexible production systems, is the distinctiveness

of Japan’s capital markets (Hollingsworth, 1997: 279). As discussed at length in Chapter

6, Japanese firms have long been dependent on outside financiers for capital, such as the

main banks and the large firms and banks of the major financial groups. These relation-

ships are strengthened by cross-ownership and interlocking directorships. This kind of

mutual stockholding obviously diversifies risk and buffers firms from the uncertainties of

labour and product markets (ibid.). ‘The extensive cross-company pattern of stock owner-

ship in Japan is an important reason why Japanese firms can forsake short-term profit

338 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 338

maximization in favor of a strategy of long-term goals – a process very much in contrast

with the pressures on American managers to maximize short-term gains. Moreover, the

patterns of intercorporate stockholding also encourages many long-term business

relationships in Japan, which in turn reinforce ties of interdependence, exchange

relations, and reciprocal trust among firms’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 280).* These kinds of

relationship have also led to low transaction costs among firms, high reliability of goods

supplied from one firm to another and close coordination of delivery schedule. ‘Because

Japanese trade associations are highly developed and span a variety of suppliers, buyers,

and related industries, they too have played an important role in developing cooperation

among competing and complementary firms, as well as in facilitating the clustering of

industries’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 283).*

‘Having the option to develop long-term strategies, large Japanese firms have had the

ability to develop the kind of long-term relations with their employees, on which invest-

ment in worker training and flexible specialization are built’ (Hollingsworth, 1997:

280).* Inter-corporate ties explain that many large firms – particularly in steel, ship-

building and other heavy industries – have been able to shift employees to other

companies within their industrial group during economic downturns rather than dis-

missing the workers altogether. Moreover, firms with long-term job security have the

capacity to implement a seniority-based wage and promotion system, which in turn, pro-

motes employee motivation and identification with the company. Long-term job security

also enables the implementation of a system of job rotation (in work teams) and flexible

job assignments, and intensive in-firm instruction and on-the-job training. In addition,

however, lifetime employment combined with seniority pay, involves a high degree of

employee dependence on the firm. Indeed, since all large firms recruit externally only for

positions at the bottom of the job hierarchy and train their specialists for better jobs

through on-the-job training and job rotation, there is no further possibility of advance-

ment outside that firm (Dohse et al., 1989). The unitary school system in Japan (see

Chapter 5 for an explanation), with its poorly developed system for providing practical or

vocational training, explains that Japanese firms offer this type of training. And, because

of the existence of long-term job security, employees and unions accept that training is

highly firm-specific and not very generalizable to other organizations. This, of course,

further increases inflexibility in the external labour market.

Moreover, as indicated, the Japanese industrial relations system is characterized by

company unions. Company unions constitute a much more advantageous arena of nego-

tiations for management than more comprehensive unions. The ties of company unions to

the individual company makethem much more strongly dependent on market success, and

hence the productivity and cost structure of their firm. As a consequence, the scope of

labour union demands is restricted; conflictual goals with respect to the utilization of

labour (i.e. working conditions) are avoided in favour of positions that can be of benefit to

both sides. This pacification function, which is inherent in the structure of the company

union, was stabilized in the 1950s through destruction of the militant unions. The inten-

sive labour struggles of the 1950s were a decisive phase in the constitution of the current

MANAGING RESOURCES: PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT 339

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 339

Japanese system of labour relations. In the course of this conflict, Japanese firms succeeded,

in particular in the automobile industry, in destroying the militant postwar unions, which

had an industry-wide orientation, and firing union representatives. In this way, Japanese

automobile industry firms were able to prevent from the outset the development of a strong

labour union movement, to particularize the interest representation of employees into

plant or company unions, and to considerably limit the scope of labour union demands.

Any discussion of the Japanese institutional configuration would be incomplete

without mention of the Japanese state. The Japanese state has been closely involved in

industrial development – though its role is somewhat less pronounced today. The Japanese

state has developed many forms of protection to keep out foreign competition, it has fos-

tered an environment for cooperation among fierce competitors, it has channelled

subsidies into targeted areas of research and development, and has encouraged and

helped firms to mobilize internal resources. Moreover, for many years, it adopted a set of

macro-economic policies designed to fuel economic growth with a yen that was under-

valued compared to the dollar (Hollingsworth, 1997: 282–3).

The German societal system of diversified quality

production

While the Japanese case is an example of a societal system that emphasizes diversified

quality mass production, the German societal system promotes another variant of flexible

production: diversified quality production in which the emphasis is less on large- and

more on small-scale production. While there are other forms of societal systems of flex-

ible production (e.g. the societal systems of flexible production in parts of northern Italy

or western Denmark), the Japanese and German systems stand out because they have

been conducive to high and continued investment in human resources in large firms.

‘Streeck and others have suggested that there is some similarity in the social systems of

flexible production of West Germany and Japan, including a high degree of social peace,

a workforce that is highly and broadly trained, a flexible labor market within firms, a rela-

tively high level of worker autonomy, a financial system with close ties between large firms

and banks, a high degree of stable and long-term relationships between assemblers and

their suppliers: overall, a social system of production, which results in very high quality

products. Despite similarity in these characteristics, there are major differences in the

social systems of production in the two countries’ (Hollingsworth, 1997: 288).*

‘In Germany, industrial unions are highly developed, whereas in Japan the emphasis

has been on company unions. In Germany, both labor and business are politically well-

entrenched in most levels of politics, whereas this is not at all the case with labor in Japan.

And in Germany, there is nothing resembling the keiretsu structure which is so prevalent

among large Japanese firms. Moreover, the Germans tend to focus on the upscale, high-

cost segments of many markets, whereas the Japanese – with their emphasis on large

market share of various products – tend to be more concerned with low-priced, but high-

quality products. In Germany, the institutional arrangements underlying the rich

340 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

* Hollingsworth, R. (1997) Continuities and changes in social systems of production: the cases of Japan,

Germany, and the United States. In Contemporary Capitalism: the Embeddedness of Institutions, edited by J. Rogers

Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press © J. Rogers Hollingsworth and Robert

Boyer 1997, reproduced with permission of the author and publisher.

MG9353 ch07.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 340