Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

track and company after twenty-one years. A similar purchase clause was put into

the Electric Lighting Act which also set maximum tariffs for electricity

supply and gave local authorities a clear mandate to set up plant. The gate to

municipalisation of electricity and trams was open and the weak regulatory

regime for gas and water in the – period was a contributory element. But

very many other factors were involved as we shall now see.

(iii)

The huge expansion of municipal water systems and gas works in the latter part

of the nineteenth century together with their promotion by the Webbs and the

Fabians prompted many observers to characterise the rise of municipal trading

as ‘gas and water socialism’. It was a useful characterisation for opponents.

‘Private capital not only complained of government regulation, but also the

stimulus given municipal socialism by the [ Electric Lighting] Act.’

24

Lord

Avebury complained of the ‘the new school of “Progressives” . . . [who] seem

to consider that we might place over any municipal buildings the motto which

Huc saw over a Chinese shop, “All sorts of business transacted here with unfail-

ing success’’’.

25

Both John Kellett and Derek Fraser have shown that municipal socialism as an

ideology was very much a phenomenon of the early decades of the twentieth

century and of debates about London government in particular.

26

It is true, as

Table . shows, that there was a massive spurt in municipal activity at this time.

The metropolitan boroughs were established under the Local Government

Act and many subsequently took to generating electricity. From to

the number of statutory electricity undertakings in Britain shot up from to

of which per cent were owned by local government. The tramways spurt

followed in the next five years; already undertakings in but by

of which one half were municipally owned. But municipalisation was clearly not

just a London matter and actually started a good half century earlier. The most

dramatic growth in statutory water undertakings was from about to the

early s by which time there were systems run by local government. For

gas the most rapid growth was from the s to the s during which period

the share of the municipals grew from per cent to per cent, remaining at

roughly that level right through to the s – though the initial spurt was most

noticeable in Scotland and the share of municipal undertakings in England and

Robert Millward

24

See p. of T. P. Hughes, ‘British electrical industry lag: –’, Technology and Culture,

(), –.

25

Avebury, ‘Municipal trading’, .

26

J. R. Kellett, ‘Municipal socialism, enterprise and trading in the Victorian city’, UHY (),

–; W. H. Fraser, ‘Municipal socialism and social policy’, in R. J. Morris and R. Rodger, eds.,

The Victorian City (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Wales continued to rise in a fairly smooth fashion through to the s. Hence,

well before the term municipal socialism was seriously bandied around, a huge

part of the shift to public ownership had taken place. In any case, as we shall see,

the political hue of town councils dominated by businessmen and ratepayers can

hardly be called socialist.

In accounting for the rise in municipal trading many writers have relied on

the monopoly argument discussed earlier. The American observers put this at

the front of their explanations. ‘All services . . . which are in the nature of

monopolies should by preference be in the hands of the Municipalities’, said the

editor of Traction and Transmission in adding that ‘private companies cannot

be trusted to exercise the powers of monopoly with discretion’.

27

A modern

writer on trams said a key element was ‘the economic argument. Tramways were

the monopoly of a public necessity.’

28

The large team of American civic officials

and academics who visited Britain in the early s subscribed to the view that

‘there is a desire to keep the city from being mulcted by a private company’.

29

In the authoritative surveys of municipal enterprise by British academics, the

monopoly issue was central.

30

Of course, other factors were often thrown in –

safety, the disruption of streets by the laying of mains and track. In fact some of

the lists become quite bewildering. The Birmingham Daily Post in claimed

to be capturing a popular mood in discerning

a general feeling that for the purposes of preventing the creation of a new monop-

oly in private hands, to ensure the control of the streets, and then to promote the

public convenience, and also to limit as far as possible, injurious competition with

Corporation gas lighting, the supply of electric light ought to be in the hands of

the local governing authority.

31

There are problems of both theory and practice in this line of argument. If

the sources of concern were the prices and profits of a private company operat-

ing in a natural monopoly setting then one solution would have been to regu-

late those prices and profits. In other words most of the above arguments might

explain the desire for public control but not necessarily the desire for public owner-

ship. Moreover, how is one to account for the behaviour of those town councils

who allowed private companies to continue – not simply the likes of Eastbourne,

Oxford and York but also industrial and commercial centres like Liverpool,

Sheffield and Newcastle did not municipalise operations in some of the utility

areas? There is also a North/South divide in some industries. ‘Geographically,

The political economy of urban utilities

27

Editor, Traction and Transmission, (), .

28

J. P. MacKay, Tramways and Trolleys (Princeton, ), p. .

29

National Civic Federation, Municipal and Private Ownership of Public Utilities (New York, ),

p. .

30

Falkus, ‘Development of municipal trading’,–; Robson, ‘Public utility services’, pp. –.

31

Quoted on p. of Lewis Jones, ‘The municipalities and the electricity supplies industry in

Birmingham’, West Midlands Studies, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Table . Number of statutory local utility undertakings in the UK –

a

Electricity Trams Gas Water

PR LG PR LG PR LG PR Munic

b

LG

— — — — n/a n/a

c

n/a

———— n/a n/a n/a

———— n/a n/a

——— —

c

n/a

— — n/a n/a n/a n/a

d

n/a n/a

e

e

f

f

n/a n/a

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

n/a n/a n/a n/a

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

n/a n/a

n/a n/a n/a

n/a n/a n/a n/a

n/a n/a

d

g

n/a n/a n/a

g

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

g

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

g

n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a

g

—————— n/a

a

PR is the private sector. LG are local authorities, including all joint boards. The data for trams refer to the ownership of track; for electricity, to

undertakings supplying electricity for light or power. Company data generally refer to financial years ending in the years quoted; for local

authorities the financial years often end in the following spring.

b

Undertakings owned by the corporations of municipal boroughs.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

c

England and Wales only.

d

Data probably exclude S. Ireland.

e

Data refer to .

f

Data refer to .

g

Excludes S. Ireland.

Sources: official: Board of Trade, Annual Returns of All Authorised Gas Undertakings ( onwards); Board of Trade, Annual Returns of Street and

Road Tramways and Light Railways ( onwards), PP ; Board of Trade, Return Relating to Authorised Electricity Supply Undertakings in the

U.K. Belonging to Local Authorities and Companies for the Year , PP / ; Balfour Committee on Industry and Trade, Further Factors in

Industrial and Commercial Efficiency; Ministry of Fuel and Power, Engineering and Financial Statistics of All Authorised Undertakings /, Electricity

Supply Act (---) (London, ). Secondary sources: A. L. Dakyns, ‘The water supply of English towns in ’, Manchester School,

(), –; M. E. Falkus, ‘The development of municipal trading in the nineteenth century’, Business History, (), –; J. Foreman-

Peck and R. Millward, Public and Private Ownership of British Industry – (Oxford, ), chs. , , , , ; E. L. Garcke, Manual of Electrical

Undertakings and Directory of Officials, vol. i: (London, ); J. A. Hassan, ‘The water industry –: a failure of public policy?’, in R.

Millward and J. Singleton, eds., The Political Economy of Nationalisation in Britain – (Cambridge, ), pp. –; W. A. Robson, ‘The

public utility services’, in H. J. Laski, W. I. Jennings and W. A. Robson, eds., A Century of Municipal Progress:The Last Years (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

most municipal gasworks were located in the industrial midlands, the north and

Scotland, though’, said Matthews ‘why some councils decided to take over their

gas works whilst others did not is not immediately obvious and the answer must

await more detailed investigation.’

32

How finally are we to account for the

differences across industries – by the s about two-fifths of gasworks were

municipally owned but it was nearer to two-thirds for electricity and four-fifths

in water supply?

Two groups had a powerful interest in these decisions. One group was man-

ufacturers and other businessmen; the other was ratepayers. The idea that many

councillors were strongly motivated by civic pride is a recurring theme in the

literature and often adduced as a reason for municipalisation – in order to ensure

high standards of service. Robert Crawford LLD, ex-councillor, member for ten

years of the Committee on Street Railways, ex-burgh magistrate, deputy lieu-

tenant of the court of the city of Glasgow etc., etc., claimed in that there

was

a large infusion among citizens of every class of the civic spirit. There is civic pride

in civic enterprise and institutions . . .The secret of success . . . lies deeper than

the mere machinery and must be sought for mainly in the honesty, uprightness,

capacity, self-sacrifice and patriotism of the men chosen by an intelligent commu-

nity and entrusted with this great communal duty.

33

But the businessmen and ratepayers had some very specific economic inter-

ests. Linda Jones has estimated that per cent of Birmingham councillors in

the period – were businessmen.

34

The fortunes of their factories were

often contingent on good local water and transport and if that required munic-

ipal operations, so be it. To take one example of business influence, Wakefield

council wished to avoid some of the health problems in taking their water supply

from the local polluted rivers by drawing on the good clean water in deep local

wells. This option was eventually dropped because the water was hard and there-

fore unsuitable for use in textile mills whose owners were well represented on

the council.

35

In all towns businessmen had a vested interest in a good water

supply for fire fighting and the American literature shows that fire insurance pre-

miums were noticeably less in towns with good water systems.

36

Robert Millward

32

Matthews, ‘Laissez-faire’, .

33

See pp. and of R. Crawford, ‘Glasgow’s experience with municipal ownership and operation’,

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, (), –.

34

See p. of L. Jones, ‘Public pursuit of private profit: liberal businessmen and municipal politics

in Birmingham, –’, Business History, (), –.

35

C. Hamlin, ‘Muddling in bumbledom: on the enormity of large sanitary improvements in four

British towns, –’, Victorian Studies, (–), –.

36

L. Anderson, ‘Hard choices: supplying water to New England Towns’, Journal of Interdisciplinary

History, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The other group, sometimes overlapping with businessmen, were ratepayers.

The last quarter of the century saw town councils in the rapidly expanding

industrial boroughs faced with immense financial burdens as they struggled to

overcome the terrible living and working conditions which industrialisation had

brought. All were investing heavily in water supply, sewerage systems and roads

and also had responsibility for the growing bill for policing and education. A

commonly quoted index is that, in the last quarter of the century, population in

Britain rose by per cent, rateable values by per cent and rates by per

cent.

37

Any device which could lower the burden on ratepayers would find ready

ears. Fraser suggests that rates were paid by the landlord in England and Wales

but by the tenant in Scotland, one outcome of which was that in Scotland

municipalities never aimed at using trading surpluses to ease the rates burden.

38

The story in England and Wales was quite the reverse, as we shall see, since

setting fares and tariffs for electricity, gas and trams at levels sufficient to gener-

ate profits which could finance urban improvements was a way of taxing non-

ratepayers, and indeed non-residents, who used the service.

The case of water supply is probably different from that of electricity, gas and

trams and nearer to the way councils organised and financed other services like

paving, refuse collection, sanitation, bathhouses and cemeteries. The

Public Health Act required local authorities to ensure that adequate water sup-

plies existed. Table . shows the average levels of local authority trading profits

each year for a sample of thirty-six towns. The water undertakings made large

operating surpluses but (as the – data show) these were usually not

enough to meet loan charges and so water undertakings generally made a

financial loss. If the object was to generate profits, the achievements were poor.

More likely the aim was to expand supplies of clean water for residents, as the

act required, and to develop soft water and a firefighting capability for

factory owners. Why, though, was water municipalised? In some respects the

issue is more difficult to pin down than the cases of electricity, gas and trams

where the large set of private operators continued to flourish and provide a

benchmark for comparison. Most of the water undertakings became municipal

and fully absorbed into local government by virtue of water charges for domes-

tic consumption being levied as a rate – a tax on the rateable value of property

like the rest of local taxation.

Some of the explanations in the literature for this shift are not convincing.

John Hassan and, much earlier, Albert Shaw and Douglas Knoop, argued that

the large-scale schemes for taking water supplies to the large urban conurbations

involved levels of finance and a degree of planning beyond the scope of private

The political economy of urban utilities

37

Millward and Sheard, ‘Urban fiscal problem’, –; M. J. Daunton, ‘Urban Britain’, in T. R.

Gourvish and A. O. Day, eds., Later Victorian Britain, – (London, ), pp. –.

38

Fraser, ‘Municipal socialism’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Robert Millward

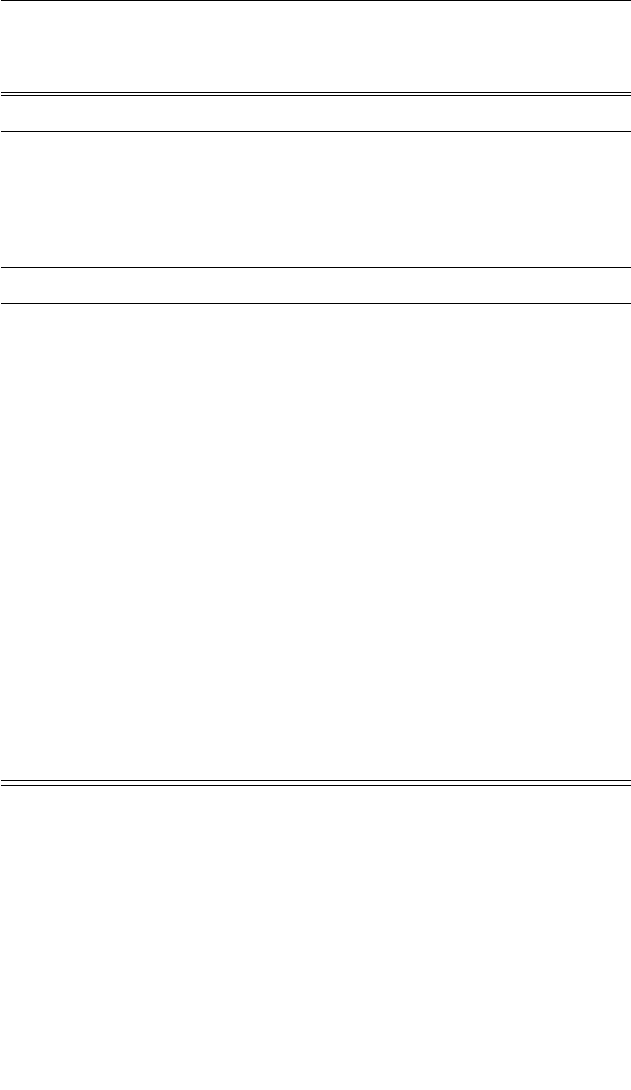

Table . Average annual gross trading profits per town council – (sample of

towns: £ )

Profits – – – – –

Water n/a .

a

. . .

Gas n/a . . . .

Markets n/a .

b

. . .

Estates n/a . . . .

Total profits .

c

. . . .

– – – –

Water

Profits ⫺. ⫺. . .

Loan charges ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a .

d

.

Gas

Profits ⫺. ⫺. . .

Loan charges ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a .

d

.

Electricity

Profits ⫺ . ⫺ . . .

Loan charges ⫺n/a ⫺ n/a . .

Trams

Profits ⫺ . ⫺. . .

Loan charges ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a . .

Market profits ⫺ . ⫺ . . .

Cemetery profits ⫺. ⫺. . .

Harbour profits ⫺. ⫺. . .

Estates profits ⫺. ⫺. . .

Total profits ⫺. ⫺. .

e

.

e

Loan charges ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a . .

Transfers (net) ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a n/a .

Balance ⫺ n/a ⫺ n/a . .

a

Excludes Leicester , , .

b

Excludes Gt Torrington .

c

Includes only some of the years for some of the towns.

d

Excludes Sunderland .

e

Excludes Thetford –.

Sources and definitions: The source is Local Government Board, Annual Local Taxation

Returns –. See below for details of the sample towns. Entries are unweighted

averages of the towns and therefore columns do not necessarily add up. Profits data

are gross trading profits. Profits of electricity, trams, cemeteries and harbours were non-

existent or zero before . Loan charges include interest; relevant aggregate data for

both these items are not available for the years before . Data refer to the financial

years of town councils ending in the year quoted.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

enterprise.

39

The investment requirements of the Rivington Pike scheme for

Liverpool in the s and the later one for Vyrnwy in Wales, the Loch Katrine

project for Glasgow in the s and the Thirlmere and Longdendale schemes

for Manchester in the s and s were certainly substantial. But private

enterprise had laid a route network for railways in the s and s equiva-

lent to our modern motorway network and the later work on lines linking the

outer reaches of Wales and Scotland involved even more costly outlays on

bridges, viaducts and tunnels. Rather, one might point to the institutional

difficulties in the way of companies earning sufficient profit to expand supplies

at a rate demanded by town councils.

That is, water supply is obviously dependent on natural resources and hence,

like agriculture, is liable to diminishing returns. Unless significant technical

progress in storage and delivery takes place, expansion will lead to rising costs.

Clearly this happened in the nineteenth century as the demands from rapid

urban population growth and industrialisation exhausted the more obvious local

The political economy of urban utilities

39

J. A. Hassan, ‘The growth and impact of the British water industry in the nineteenth century’,

Ec.HR, nd series, (), –; A. Shaw, ‘Glasgow: a municipal study’, Century, (),

–; D. Knoop, Principles and Methods of Municipal Trading (London, ).

Table . (cont.)

The sample of towns: the location of each of the sample of towns and their status in

are as follows.

North Midlands South

& Wales

County boroughs Blackpool Bristol Hastings

Bradford Hanley Norwich

Leeds Leicester Plymouth

Liverpool Lincoln Southampton

Manchester Northampton

St Helens Nottingham

Sunderland Oxford

Preston Swansea

York Wolverhampton

Boroughs Carlisle Carmarthen Gt Torrington

Doncaster Louth Kingston

Richmond Luton Marlborough

Wrexham Ramsgate

Shaftesbury

Thetford

Urban district councils Tottenham

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

supplies and towns had to look further afield. Data on the cost of water are actu-

ally quite meagre but Jose Cavalcanti’s recent work on supplies to London sug-

gests that costs per gallon did rise. The annual supply of all the London water

companies came to , million gallons in and rose to , million by

. His estimates of the companies’ total annual costs are £, in

and £,, in , implying that the costs per thousand gallons rose by

per cent from d. to d.

40

Relative to the prices of all other goods and services,

most of which were falling, the real cost of water may have risen by about

per cent in the nineteenth century. For the companies to make a normal rate of

return, water charges would have had to rise accordingly and large numbers of

customers captured in order to exploit the economies of scale and contiguity

central to keeping costs per unit down. This is where the maximum prices

specified in the legislation did appear to bite. A contemporary authority, Arthur

Silverthorne, suggested the maxima allowed in the Clauses Act were never

high enough for the companies and so they, instead, engaged in protracted legal

battles over the valuation of property to which the water rate was applied.

41

Most

business customers were metered; for example, another contemporary reported

that in a sample of twenty-nine undertakings all ‘trade’ customers were supplied

by meter.

42

Many councils dominated by manufacturers had meter schedules

which were very generous as was the ‘compensation’ water allowed to factories

operating near rivers and reservoirs subject to development in water schemes.

None of this meant profit for the water companies. Similarly, it was important

for the companies to capture large numbers of customers given the ‘lumpiness’

of the investment required in water resource development. Ideally such custom-

ers should be geographically concentrated in order to take advantage of the

economies of contiguity inherent in distribution networks. A major problem

which the companies therefore faced was that for constant high pressure supply

to be introduced – which all parliamentary reports were promoting – it was

essential for customers themselves to invest in pipes, sinks and drains in their own

homes. A great deal of uncertainty therefore surrounded the operation of com-

panies dealing on a one to one basis with households, some of whom would be

reluctant to make the necessary investments. A great attraction of municipal

operation was that it involved the finance of water services to households by

rates, the tax on rateable values. By such a uniform levy, councils automatically

enrolled all ratepayers on to the water undertakings’ books.

43

For electricity, trams and gas different issues were involved. One was the desire

to curb the excess profits that would arise when private enterprise were left to

Robert Millward

40

Cavalcanti, Economic Aspects, tables ., ., ., ..

41

A. Silverthorne, London and Provincial Water Supplies (London, ), pp. , , .

42

See pp. – of W. Sherratt, ‘Water supply to large towns’, Journal of the Manchester Geographical

Society, (), –.

43

Royal Commission on Water Supply, Report of the Commissioners (), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

operate services which were natural monopolies. On the face of it this could be

done by controlling fares and tariffs and by taxing profits. Such local taxes and

controls were often not available to local authorities in Britain, unlike

Germany.

44

This helps to explain municipalisation in Scotland where in addition

the companies were cheap to buy out since the law never gave them the right

to operate in perpetuity, as in England and Wales. For the latter, our thesis is that

a driving force behind municipalisation was the desire of local councils to get

their hands on the surpluses of these trading enterprises and use them to ‘relieve

the rates’. This was Joseph Chamberlain’s dictum. Unless a council had substan-

tial property income (‘estates’), essential town improvements would be deferred

unless some revenue other than rates was found.

45

But if it was paramount why

did York, Bournemouth, Salisbury and many others refrain from extensive

municipal trading? Why did Liverpool, Bristol and Hull allow private gas com-

panies to flourish? Why was there the North/South dichotomy reported by

Matthews?

46

It is important to recognise that in the early years of the century, the owners

of the private companies – gas only at that stage of course – were often major

local ratepayers. Together with bankers, lawyers and other professionals, they

would form the local body of improvement commissioners or councillors.

47

By

the late nineteenth century they were a much more dispersed group as capital

came from various sources and the local ratepayers were as likely to be domi-

nated by shopkeepers.

48

Many of the growing industrial towns of the Midlands

and the North faced a substantial fiscal problem emanating from the rising

demands for expenditures on public health, roads, policing, poor relief, educa-

tion and other services. The local authorities had little room for manoeuvre since

they had no powers to raise income taxes or levy duties on commodities or

profits or land. Some grants and assigned revenues emerged from central govern-

ment in the last decades of the century

49

but, in general, little was done to alle-

viate the widely differing circumstances of the local authorities. The ratepayers

staged revolts but also, as Peter Hennock noted, they looked for alternative

revenue sources. The ports of Liverpool, Swansea, Bristol, Hull, Yarmouth and

The political economy of urban utilities

44

J. C. Brown, ‘Coping with crisis: the diffusion of water works in the late nineteenth century

German towns’, Journal of Economic History, (), –.

45

Fraser, ‘Municipal socialism’, p. ; P. J. Waller, Town, City and Nation (Oxford, ), p. .

46

Matthews, ‘Laissez-faire’.

47

For Preston see B. W. Awty, ‘The introduction of gas lighting to Preston’, Transactions of the History

Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, (); for Chester see J. F. Wilson, ‘Competition in the

early gas industry: the case of Chester Gas Light Company –’, Transactions of the

Antiquarian Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, (), –.

48

E. P. Hennock, Fit and Proper Persons (London, ); J. Garrard, Leadership and Power in Victorian

Industrial Towns, – (Manchester, ).

49

G. C. Baugh, ‘Government grants in aid of the rates in England and Wales, –’, Bull.

IHR, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008