Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

residential environments of the garden cities attractive. The garden city concept

inspired the development of other planned communities, with industry zoned

on estates, by the Corporations of Manchester and Liverpool, and influenced

similar, smaller-scale, projects by private developers such as John Laing & Sons

and the Thames Land Co.

84

Following the end of the First World War a large number of modern single-

storey factories built for the war effort became available for civilian use. Some of

these, typically on the edges of the London conurbation in areas such as Park

Royal, Slough and Hendon, stimulated the development of further factories,

often available for renting, forming the nuclei of industrial estates. At a time

when finance for growing industrial enterprises in the new industries was not

readily provided by the City, renting factories on industrial estates, which avoided

sinking capital in factory premises and might thus reduce total start-up costs for

a small manufacturer by per cent or more, appeared extremely attractive. By

there were at least sixty-five industrial estates in Britain, employing around

, people.

85

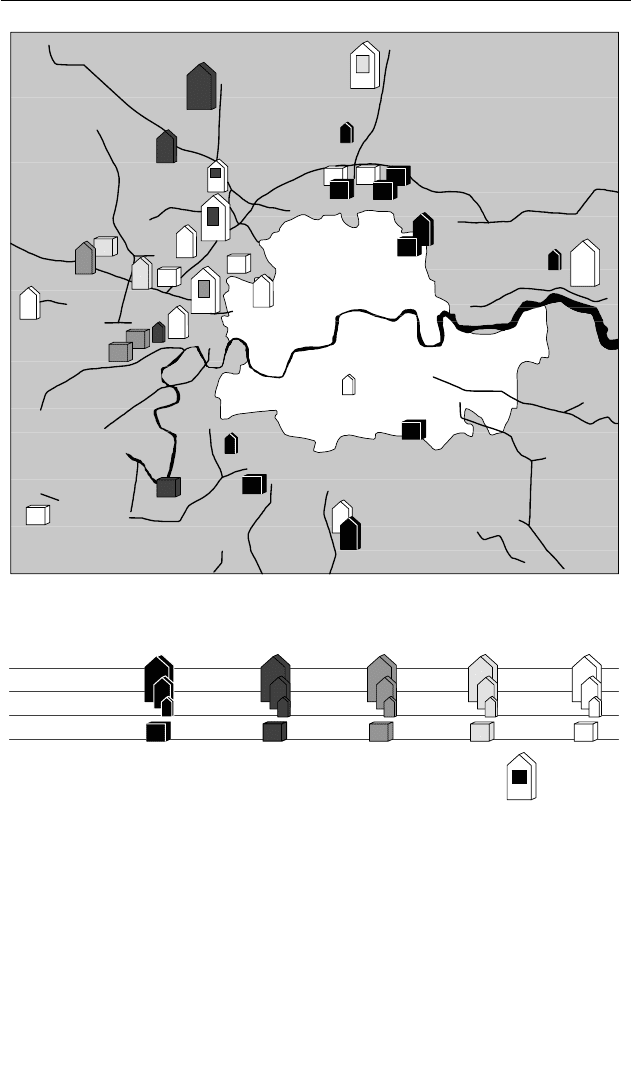

About per cent of workers on industrial estates were located

in the South-East, many in estates along London’s arterial roads, illustrated in

Figure .. Estate occupants were typically inner-London firms which had

decentralised in order to obtain larger, more modern premises, that were better

situated (particularly with regard to road transport). A similar trend of outward

industrial migration occurred in the Birmingham conurbation, though this was

almost entirely based around ribbon development rather than industrial estates.

86

A lack of modern factory premises, built for renting, compounded the prob-

lems that Britain’s traditional industrial areas faced in attracting new industry as

a result of their relatively poor road transport networks, depressed local econo-

mies and remoteness from Britain’s largest and most prosperous centre, London.

Declining textile areas benefited from vacant factory space; for example twenty-

six of the twenty-eight new firms established in Long Eaton between and

occupied former lace mills.

87

However, industrial areas dominated by steel,

coal or shipbuilding could offer no such facilities, while former textile factories

proved less attractive than modern factory premises. The government was even-

tually persuaded, reluctantly, to remedy the lack of appropriate factory infra-

structure in the depressed areas via a very limited programme of

government-financed industrial estate development (together with other meas-

ures of assistance) during the mid-late s, as discussed in Chapter .

Peter Scott

84

P. Scott, ‘Planning for profit: the Garden City concept and private sector industrial estate devel-

opment during the inter-war years,’ Planning History, (), –.

85

P. Scott, ‘Industrial estates and British industrial development: –’, Business History,

(forthcoming).

86

Nuffield College, Oxford, Archive, Nuffield College Social Reconstruction Survey Papers, C/,

‘West Midlands Regional Report (Part A)’ (October ). See also below, pp. ‒.

87

J. M. Hunter, ‘Factors affecting the location and growth of industry in Greater Nottinghamshire’,

East Midland Geographer, (), .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The evolution of Britain’s urban built environment

Developer Commercial

Structures Ltd

John Laing

& Son Ltd

Allnatt

Ltd

Percy Bilton

Ltd

Others

>100 acres

20–100 acres

<20 acres

Unknown acreage

Estates involving more than one developer are indicated by a combined

symbol e.g.: Commercial Structures Ltd with others

Figure . Industrial estates and arterial roads in Greater London c.

Note: this map omits one estate for which insufficient information is available

regarding location and uses one symbol for directly contiguous estates.

Source: P. Scott, ‘Industrial estates and British industrial development,

–’, Business History, (forthcoming).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

(iv)

The onset of the Second World War led to a virtual halt in property market activ-

ity and a severe fall in commercial property values, particularly in London.

Property speculators and developers were only saved from widespread bankrupt-

cies by a voluntary moratorium on loans on the part of insurance companies,

building societies and other lenders, though in a few cases insurance companies

did foreclose on mortgages. However, despite extreme political and economic

uncertainty, together with the physical danger to property from bomb damage,

a number of far-sighted entrepreneurs began to purchase property during the

war. The rationale behind such investment was simple; if the Allies were vic-

torious property values would appreciate substantially, while if the Germans

invaded Britain it would be of little importance where they had invested their

money.

88

Speculators and developers also invested in bomb-damaged sites;

bombing cleared large central areas which, if consolidated into single plots,

might eventually be used to develop substantial buildings.

Following Labour’s election victory the property sector, like many other

areas of the economy, experienced a level of government intervention that was

unprecedented in peacetime. Building licences severely restricted the volume of

commercial property development, in order to direct scarce building materials to

priority sectors. The Town and Country Planning Act provided the frame-

work for more permanent post-war town planning controls, bringing almost all

development under government control by making it subject to planning per-

mission. Development rights and the development value of land were effectively

nationalised by the act, leaving landowners with their existing () use rights

and land values.

89

Compensation for the loss of development rights was to be paid

from a national fund, while developers had to pay a levy amounting to per

cent of any increase in land values resulting from new development.

The imposition of a per cent tax on property development removed any

incentive to develop property. A system of building licences, capital issues con-

trols and other regulations, together with an acute shortage of building materi-

als, placed further obstacles in the path of the developer, with the result that there

was little development of new commercial property during – outside a

few narrow areas. Most commercial property development that did occur was

permitted by government according to one of three criteria. Properties which

might collapse, or otherwise endanger the public, if they did not receive atten-

tion were given top priority. ‘Dangerous structure notices’ were issued, enabling

the owner to obtain a building licence.

90

Firms which were involved in eco-

Peter Scott

88

Marriott, Property Boom, p. .

89

Cullingworth, Town and Country, p. .

90

J. Rose, The Dynamics of Urban Property Development (London, ), p. . There is evidence

that this legislation was often abused in practice, via the granting of licences for structurally sound

buildings.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

nomic activity considered essential to Britain’s post-war recovery, such as man-

ufacturers producing goods for export, were also given high priority for essen-

tial redevelopment work. Finally, there was a considerable demand for new

property for the government’s own use. Developers built offices for government

occupation under ‘lessor schemes’, licences being granted in return for the

developer’s agreement to let the building to the government at a pre-determined

rent.

Meanwhile, the supply of commercial property had been substantially

reduced by the war; bombing had damaged or destroyed , shops, ,

commercial properties and , factories.

91

This damage was concentrated in

London and a number of ports and important industrial centres, such as Bristol,

Hull, Portsmouth and Coventry. Within London the worst hit area was the City,

with a third of buildings totally destroyed. Furthermore, requisitioning led to

many commercial enterprises losing the use of their premises for some time after

the war. Given the shortage of commercial premises arising from these condi-

tions, property values inevitably soared, stimulating an investment boom on the

part of institutional and private investors. There was also a boom in corporate

property investment; many of Britain’s largest property companies, such as Land

Securities, MEPC and Hammersons, were founded during the years –.

Rising property values also played an important part in the hostile takeover

boom of the early–mid-s. Corporate raiders such as Charles Clore, Isaac

Wolfson and Hugh Fraser found that they could use the sale and leaseback mech-

anism to acquire entire companies in property-rich sectors such as property,

retailing and hotels, with undervalued property assets (their balance sheet values

typically being based on purchase costs minus depreciation). In an era when high

corporate taxation depressed dividends (and, therefore, share values) it was often

possible to acquire such companies for less money than could subsequently be

raised from the sale of their properties to an insurance company, simultaneously

leasing them back for years to preserve the company’s value as a going

concern.

The election of a Conservative government in led to a substantial water-

ing-down of Labour’s town planning legislation. The Town and Country

Planning Act of removed the per cent development levy introduced

by the act and in November the other major impediment to property

development, building licences, was abolished, following several years of their

gradual relaxation. Meanwhile, building materials shortages, which would have

restricted development even in the absence of controls, had substantially eased.

The newly deregulated commercial property sector faced very buoyant

demand. In addition to pent-up demand arising from the lack of new develop-

ment during the previous fifteen years, the service sector was experiencing rapid

The evolution of Britain’s urban built environment

91

B. P. Whitehouse, Partners in Property (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

expansion, growing by . per cent in terms of real GDP from to .

The result was an unprecedented development boom. During to the

value of commercial construction averaged £, million in real () prices,

compared to an average of only £ million during the previous nine years.

92

During the s property development was probably the most prosperous

sector of the British economy. Marriott estimated that no fewer than people

became millionaires between and as a result of their activities in this

sector, most of whom started their careers without any capital ‘beyond the odd

hundred pounds’.

93

These included many of the most prominent entrepreneurs

of the era, such as Charles Clore, Jack Cotton and Harold Samuel. Conversely,

there were very few examples of business failures in the property sector during

this period, in contrast to its experience during the s and s.

The boom was based on institutional finance and individual talent; as the

property entrepreneurs usually had little initial capital they relied on the financial

institutions to fund their operations. The property boom years saw a substantial

rise in the level of both direct institutional investment in property and the pro-

vision of development finance.

94

A very substantial volume of institutional funds

was also channelled to the property company sector via mortgage finance and

institutional purchases of property company shares. By the mid-s some

astute institutional investors were reacting to accelerating inflation by searching

for ways to conduct property investment and development finance so as to obtain

a share of the future capital appreciation of the assets in which they invested.

This led to a number of innovations, the most important of which was the rent

review.

Rent review clauses, introduced around , provided for upward only revi-

sions in rents to market levels, at regular intervals specified within leases. Reviews

were first introduced only at relatively long intervals, typically every thirty-three

years, leaving the property developer with most of the ‘equity’ of the property

assets concerned. Over the years – rents for vacant city offices increased

at an average compound rate of approximately per cent per annum,

95

while, as

a result of rents being fixed for long periods within leases, the capital return on

investment property averaged only . per cent.

96

However, a gradual reduction

in the interval between rent reviews over the following decades was to transform

property from a fixed-interest security to an equity investment. A similar trans-

formation occurred in the property development finance market; from the late

s a substantial number of institutional investors abandoned their previous

policy of providing fixed interest mortgage finance in favour of packages which

Peter Scott

92

Sources: –, M.C. Fleming, ‘Construction and the related professions’, in W. F. Maunder,

ed., Reviews of United Kingdom Statistical Sources, vol. (Oxford, ); –, CSO, Annual

Abstract of Statistics (various issues). As the figures for and are based on different (govern-

ment) sources there may be some degree of distortion, though this is not likely to be great.

93

Marriott, Property Boom, p. .

94

Scott, Property Masters, pp. –.

95

Rose, Dynamics, p. .

96

Scott, Property Masters, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

offered them an equity stake in the property companies whose activities they

funded.

While the property boom massively increased the scale and prosperity of the

British property development industry it did little to enhance the developer’s

public image. Property developers regularly exploited various flaws and loop-

holes in the post-war planning controls, undertaking development which was

against the spirit, but not the letter, of the legislation. Another source of bad

publicity concerned the demolition of historic buildings to make way for new

office blocks. The s saw a substantial increase in public concern regarding

the loss of Britain’s building heritage, a large number of notable buildings being

replaced by what were widely regarded as some of the ugliest buildings ever seen

in Britain’s cities. The developer’s image was also tarnished by a small number

of cases of straightforward corruption, though scandals involving prominent

figures in the industry were relatively few, certainly far fewer than were produced

by the financial services boom of the s.

The s property boom, like all development booms, contained the seeds

of its own destruction. By the early s City office floor space was expanding

at such a rate that significant oversupply was inevitable within a few years, reduc-

ing rents and leading to a downturn in development activity. In the event this

was not allowed to take place, due to the introduction of the Brown Ban

97

on

office development in and around London, by the Labour government.

This marked the end of the ‘golden age’ of the British property development

industry, subsequent booms (in the early s and mid-late s) being fol-

lowed by severe crashes within a few years.

The s was a period of unprecedented prosperity for the building indus-

try, demonstrated by both rising employment (,, in , compared with

, in ), and increased industrial concentration. Firms employing over

ten people accounted for . per cent of building employment in com-

pared to . per cent in ; the respective figures for firms employing or

more were . per cent and . per cent.

98

Full employment contributed to

rising building costs, but also served to stimulate innovation and efficiency

improvements, since it was no longer possible to hire labour on a casual basis and

lay it off during breaks in the work schedule.

99

The post-war years saw substantial further growth of the office sector; office

work expanded from per cent of total employment before the war to per

cent in , reflecting the growth of government, the tertiary sector and

administrative jobs within manufacturing.

100

Following the lifting of building

licence controls in November the City, and other major office centres,

entered a phase of unprecedented growth. In addition to the office requirements

The evolution of Britain’s urban built environment

197

‘Full stop for London offices’, Economist, ( Nov. ), pp. –.

198

Bowley, British Building Industry, pp. –.

99

Ibid., pp. –.

100

D. Cadman and A. Catalano, Property Development in the UK (Reading, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

of the City’s traditional business occupants, many of the country’s largest indus-

trial companies sought prestige headquarters at the heart of Britain’s capital,

divorcing their administrative centres from their factory premises.

The City’s attractions as a headquarters location included its large number of

business and financial service firms, enabling companies to buy in these services

rather than providing them internally. The growing internationalisation of

British industry was a further factor leading to the concentration of head offices

in London, due to the greater need for international connections and associated

services. The post-war merger movement also increased the number of head

offices in London, given the strong relationship between company size and the

geographical separation of head office and manufacturing activities. Despite fears

of congestion in the City, decentralisation had already begun during the s

(largely in response to soaring City office costs), becoming apparent by the end

of the decade. However, decentralisation did not progress far beyond the edges

of the conurbation, building in the London region accounting for an estimated

per cent of all new office floor space in England and Wales over –.

101

Skyscapers of over twelve floors were still exceptional during the s. Offices

in smaller towns were generally of one to five storeys, while even in larger urban

centres office blocks were generally only five to twelve storeys high. Offices were

generally designed along functional lines, to minimise costs and maximise floor

space within ‘plot ratio’and other planning restrictions. They were produced eco-

nomically (by the standards of the contemporary construction industry), but were

generally lacking both in aesthetic appeal and in such practical considerations as

quality, durability and amenities. As Jack Rose, one of the most active office devel-

opers during this period, recalled, ‘In essence, the standard of building conformed

to the sellers’ market.’

102

There were, however, a few more prestigious and inno-

vative developments. For example, Fountain House in Fenchurch Street, built

during –, introduced the New York style of setting a tower at one end of a

low-built podium and was also one of the first British offices to use curtain walls.

This construction technique – which was later to become associated with lower-

quality developments – involved hanging external walls (usually made predomi-

nantly from glass) from the concrete floors like curtains.

During the immediate post-war years austerity, tight government controls and

restrictions on new property development had drastically limited competition

and change in the retail sector. However, by the s the rising volume of retail

trade was producing pressure for further change; by the end of the value of

GDP accounted for by the distributive trades had increased by more than one

third, in real terms, compared to . Further pressure for retail development

arose from the trend towards self-service retailing. This was pioneered by the

Peter Scott

101

S. Taylor, ‘A study of post-war office developments’, Journal of the Town Planning Institute,

(), .

102

Rose, Dynamics, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Co-operative movement, which opened Britain’s first self-service grocery store,

in Portsmouth, in .

103

During the late s the Ministry of Food had taken steps to encourage self-

service retailing, offering a hundred special building licences to retailers prepared

to experiment with self-service conversion and share their experiences with

other interested parties.

104

However, despite a positive response to this initiative

it was not until the mid-s that the removal of building restrictions allowed

the number of self-service stores to become substantial. By the middle of

there were at least supermarkets in Britain; five and a half years later their

numbers had increased more than tenfold to about ,.

105

Serving a popula-

tion that was still not largely car-borne, early supermarkets were generally

restricted to units of under , sq. ft ( sq. m), in central locations.

Nevertheless, their development called for a substantial increase in average store

floor space, while many non-food multiples also wished to develop significantly

larger premises. The demand for major shopping centre developments was there-

fore considerable; by seventy large-scale central area shopping schemes

were awaiting ministerial approval.

106

Major s shopping developments were often based on fully or partly

pedestrianised precincts, pioneered in American suburban centres prior to the

Second World War. However, by the end of the decade the first schemes for

covered shopping centres (also inspired by American developments) were being

considered, such as the Elephant and Castle Centre in London, and Birming-

ham’s Bull Ring Centre. By , therefore, the stage was set for further sub-

stantial changes in both the scale and form of central area shopping development.

During the s and s factory design remained broadly along s

lines, though materials shortages led to the demise of the elaborate façades which

fronted many interwar factories. Factory location was subject to unprecedented

control, via location of industry legislation designed to direct industry towards

the regionally assisted Development Areas. Building licences, supplemented in

by Industrial Development Certificates, prevented industrialists from build-

ing or extending factory premises of over , sq. ft ( sq. m) without

government approval. Meanwhile, the government undertook extensive factory

building in the Development Areas during the immediate post-war period,

much of which was located on industrial estates developed (or converted from

wartime Royal Ordnance Factories) by government-financed companies.

The Conservative government drastically reduced the volume of

government factory construction in the Development Areas and permitted more

industrial development in the prosperous Midlands and South-East (trends

The evolution of Britain’s urban built environment

103

H. Mason, ‘The twentieth-century economy’, in B. Stapleton and J. H. Thomas, eds., The

Portsmouth Region (London, ), p. .

104

Williams, Best Butter, pp. –.

105

W. G. McClelland, Studies in Retailing (Oxford, ), p. .

106

Cadman and Catalano, Property Development, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

which were already visible during Labour’s final years in office). Low unemploy-

ment in Britain’s formerly depressed regions reduced political pressures for an

active regional policy, while government intervention in the location of indus-

try was seen as being in conflict with the government’s national economic policy

framework and its non-interventionist economic philosophy.

107

This downgrad-

ing of regional policy was partially reversed at the end of the decade, due to a

renewed rise in regional unemployment which was to prove a long-term feature

of the British economy.

Substantial government-sponsored factory development did occur during the

s under another initiative, New Town development. The Labour govern-

ment had initiated fourteen New Towns between and as part of its

comprehensive town planning framework; eight were located on the fringes of

the London region, to decentralise the metropolis’s population, together with

six provincial New Towns. While the provincial New Towns were mainly con-

nected with existing or planned industry, the London New Towns required the

creation of an almost entirely new industrial base. Little development took place

during Labour’s time in office, due to legal problems and materials shortages.

However, the Conservatives substantially accelerated the New Towns pro-

gramme, as New Town housing development constituted a convenient means of

fulfilling part of their pledge to build , new homes. During the s

London New Town factory construction (undertaken by the government-

financed New Town Development Corporations on one or more industrial

estates within each town) substantially exceeded government-sponsored factory

development in Britain’s declining regions.

108

Meanwhile, the development of private sector industrial estates was largely

suppressed by the continuing need for Industrial Development Certificates,

which prevented the speculative development of factory premises. By failing

actively to plan industrial development so as to protect Britain’s declining

regions, or abolish Industrial Development Certificates and leave firms to locate

where they chose, government location of industry policy during the s

achieved neither the potential benefits of planning nor laissez-faire. Furthermore,

the London New Towns programme directed the lion’s share of government-

sponsored industrial development to the already prosperous London region.

(v)

By the s retailing and office functions had become concentrated in partic-

ular districts within central urban areas, while manufacturing had moved out to

Peter Scott

107

P. Scott, ‘The worst of both worlds: British regional policy, –’, Business History,

(), –.

108

P. Scott, ‘Dispersion versus decentralisation: British location of industry policies and regional

development –’, Economy and Society, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

zones on the fringes of towns and cities. Economic and technological develop-

ments had exerted a powerful impetus to the process of functional and geograph-

ical concentration of non-residential property, town planning legislation (which

was largely ineffective in its zoning powers prior to ) merely formalising

trends towards geographical specialisation which had been gathering pace for

many decades. This geographical and functional specialisation reached its zenith

during the s and s. Thereafter, it has been increasingly reversed by eco-

nomic, social and technological developments which have led to the decentral-

isation of some office and retailing activities to edge-of-town and out-of-town

locations, while more recently the information technology revolution has raised

the possibility of the home once again becoming a significant location for some

of the activities currently undertaken in specialist commercial buildings.

The evolution of Britain’s urban built environment

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008