Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

·

·

The planners and the public

I

current literature, it is often asserted that the planning system which

emerged in mid-twentieth-century Britain was remarkably and regrettably

undemocratic. Planners had long wished to impose their own idiosyncratic

ideas and now found themselves legally entitled to do so. Ordinary people’s

wishes were ignored, as common sense was jettisoned in favour of dogma. The

schemes that resulted won plaudits in professional competitions but were rarely

liked by the public. In the long term, some believe, this ‘reform from above’

actually exacerbated the urban decay and social deprivation it set out to allevi-

ate. Many would no doubt instinctively sympathise with Lady Thatcher’s robust

declaration at the Conservative Conference that planners were culpable:

they had ‘cut the heart out of our cities’.

1

In the following chapter, we scrutinise some of the basic historical compo-

nents of this pervasive view and show that they are far too simplistic. Town plan-

ners in Britain had always meditated on the question of public participation,

even if their solutions were sometimes vague or actually ambiguous. Moreover,

the planning system created by Labour after the Second World War was relatively

open and allowed – often encouraged – involvement from ordinary citizens.

Planners and planned, it is true, did not always coexist happily under the new

legislation, but this was not because the former simply ignored the latter. To

understand the problems that developed means, in our view, admitting into the

analysis factors that are frequently ignored, particularly the question of finance,

the local government milieu in which planning occurred and the precise

configuration of real (as opposed to assumed) popular thinking about the urban

environment at this time.

The town planning movement which coalesced in Britain at the end of the

nineteenth century was an eclectic mix of influences and interests. It contained

The authors would like to thank Martin Daunton, Steven Fielding, Junichi Hasegawa and Tatsuya

Tsubaki for help and advice in their research for this chapter.

1

M. Thatcher, Speeches to the Conservative Party Conference – (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

elements of the technical and professional disciplines of architecture, surveying

and sanitary inspection, and drew intellectual support from the developing aca-

demic fields of geography, geology, sociology and social psychology. It was

informed by the pragmatic experience of late Victorian and Edwardian environ-

mental reform and, simultaneously, by the philosophies of social conservatism,

liberal progressivism and utopian socialism.

2

It was the preserve of the visionary

and the technician and was both liberating and highly prescriptive. The precise

sources of inspiration and impetus are still unclear, and it is not the purpose of

this chapter to explore them in any depth. Nevertheless, it is important to note

the composite nature of the discipline during its formative years: an understand-

ing of the often contradictory messages informing the planning process may help

to explain the at times problematic relationship which emerged between the

practitioners of planning and the public.

During the first half of the twentieth century, public participation in the plan-

ning process was advocated by a number of social commentators, a few politi-

cians and, most consistently, by leading planning experts, but this professed ideal

was complicated by a concurrent emphasis on the edifying nature of good plan-

ning. Participatory citizens, supportive of cohesive and dynamic communities,

were sought but, it was widely felt, first required instruction and tangible exam-

ples. This prescriptive accent reflected both the nature of the developing town

planning movement and the intellectual environment into which it was received.

In the early twentieth century, a keen interest in the relationship between the

physical environment and social organisation developed among middle-class

professionals and policy makers. A language of social improvement emerged that

was an amalgam of Darwinian and Larmarckian theories of evolution, the social

philosophy of Herbert Spencer, the radical reformism of Robert Owen and John

Stuart Mill, and the pragmatic experience of half a century of public health

policy.

3

The notion of town planning was part of this rhetoric. Drawing support

and personnel from an assortment of progressive groups and from a preventive

health lobby which had long advocated the social importance of environmental

improvements, as well as financial backing from prominent politicians and busi-

nessmen with an affinity for the notion of regeneration (for national efficiency,

if not ethical or spiritual reasons), a town planning movement began to press the

case for housing and land-use reform.

4

At the centre of their advocacy lay the

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

2

P. Hall, Cities of Tomorrow (Oxford, ).

3

D. Porter, ‘“Enemies of the race”: biologism, environmentalism and public health in Edwardian

England’, Victorian Studies, (), –; J. Harris, Private Lives, Public Spirit: Britain, –

(Harmondsworth, edn), pp. –.

4

On ‘national efficiency’ see G. Searle, The Quest for National Efficiency:A Study in British Politics and

Political Thought, – (Oxford, ). The Birmingham housing reform advocate, J. S.

Nettlefold, part of Joseph Chamberlian’s network, cited national efficiency as one of the factors

motivating his call for housing reform. See J. S. Nettlefold, A Housing Policy (Birmingham, ),

and Practical Town Planning (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

relationship between the built environment and the community. Good town

planning, in conjunction with other ameliorative reforms, could favourably

influence not just the health but the spirit of the nation.

The beneficial, indeed edifying, influence of a good physical environment had

emerged as a strong theme in a number of late Victorian housing and social

reform experiments. Tangible examples of this pragmatic ‘idealism’, for instance,

were seen in the settlement house movement, and perhaps most notably in

Canon Samuel Barnett’s project at Toynbee Hall in the East End of London,

5

and in the housing refurbishment and management schemes of Octavia Hill

which had been supported (financially and morally) by John Ruskin from the

s.

6

Urban improvement, as espoused by Barnett and Hill, was a social as well

as a physical activity which, crucially, hinged on the development of positive

relationships between individual citizens and their environment. Hill’s housing

reform efforts, for example, focused on her tenants rather than on the actual

fabric of the buildings she took over. Through personal intervention and door-

to-door contact by Hill and her team of women housing workers, tenants were

encouraged, through a combination of incentives and penalties, to assume

responsibility for the maintenance and improvement of their own homes. As

Helen Meller has recently argued, for Hill, ‘urban renewal took place around a

healthy community’, the development of which was first and foremost ‘a matter

of personal caring’.

7

Canon Barnett’s work in Whitechapel, centred on the uni-

versity settlement at Toynbee Hall, similarly invested in personal relationships,

and the mutual learning which could arise from a closer interaction of wealthy

and poor, of the cultured and the unrefined.

8

Both projects were clearly

restricted by the numbers of people who could be reached in this way.

Nevertheless, significant elements of their message, if not their methods, were

taken up by the emerging town planning movement which, composed largely

of a mixture of idealist (often idiosyncratic) reformers and, from the s

onwards, technical experts eager to carve out a professional identity for them-

selves, contained a distinctly didactic message.

The work of Raymond Unwin, planner and architect, along with his cousin

Barry Parker, on the first Garden City at Letchworth between and

The planners and the public

5

H. O. Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life,Work and Friends (London, edn); A. Briggs and A.

Macartney, Toynbee Hall: The First Hundred Years (London, ).

6

O. Hill, Homes of the London Poor (London, ; repr. ); O. Hill, House Property and its

Management (London, ); O. Hill, ‘Management of homes for the poor’, in her Letters to my

Fellow Workers (published privately, –). See also A. Power, ‘The development of unpopular

housing estates and attempted remedies, –’(PhD thesis, University of London, ), pp.

–.

7

H. E. Meller, ‘Urban renewal and citizenship: the quality of life in British cities, –’, UH,

(), .

8

Ibid., –; Barnett, Canon Barnett; Briggs and Macartney, Toynbee Hall. See also S. A. and H. O.

Barnett, Towards Social Reform (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

(and also on much of Hampstead Garden Suburb, the co-partnership housing

development initiated by Henrietta Barnett, wife of Canon Barnett), illustrates

the ambiguities which this didacticism brought to the developing relationship

between the planner and the planned. Unwin’s work was deeply influenced by

his political views. He was a socialist in the mould of Edward Carpenter and

William Morris who believed that social progress was obtainable through the

substitution of the values of community and human dignity for class antago-

nism. Influenced by Morris and also by John Ruskin in his early years, Unwin

shared their conviction that beauty could be found in all aspects of daily life and

should be positively cultivated by, and for, all.

9

He also took from them, and

from the wider ‘Arts and Crafts’ fraternity, the belief that form should reflect

function.

10

Town and housing design offered him a medium through which to

explore these conjunctions between art, life and morality. In Unwin’s view, a

reciprocal and interactive relationship existed between the built environment

and the community. Social coherence, for instance, could be encouraged

through the visual coherence of a place, and a sense of community enhanced

by the ‘aesthetic control’of building materials, housing design and layout.

11

This

conception of town planning, however, contained an equivocal message about

the role of the ordinary citizen in the planning process. If a town’s design and

architecture was to reflect, and indeed shape, the spirit and the purpose of ‘the

individual lives lived within’ it, then who was to decide or interpret what that

spirit and purposes should be?

12

Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin both con-

sidered town planning (or ‘civic art’ as they had originally called it) a ‘demo-

cratic art’, believing that the public should participate in the plan-making

process. The role of the architect-planner was to give physical shape to the needs

and aspirations of a community.

13

This commitment to democratic planning,

however, was underwritten by a belief that ultimate responsibility must lie with

the architect. As the ‘disinterested mentors’ of the citizens of ‘England’s emerg-

ing democracy’, architects would teach the people, ‘through the experience of

living within healthy, liberating environments’, the ‘difference between good

architecture and bad’, helping them to develop ‘a worthy moral aesthetic of

their own’.

14

The inherent tension between these two aspects of Unwin and Parker’s plan-

ning philosophy can be seen in their rejection of the parlour in cottages designed

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

19

S. Meacham, ‘Raymond Unwin, –: designing for democracy in Edwardian England’,

in S. Pedersen and P. Mandler, eds., After the Victorians (London, ), pp. –.

10

C. F. A. Voysey, C. R. Ashbee, W. R. Lethaby, M. H. Baillie Scott and many other designers and

architects contemporary to them all carried references to Morris in their work.

11

R. Unwin and B. Parker, The Art of Building a Home (London, ), pp. –.

12

Meacham, ‘Raymond Unwin’, p. .

13

M.G. Day, ‘The contribution of Sir Raymond Unwin and R. Barry Parker to the development

of site planning theory and practice c. –’, in A. Sutcliffe, ed., British Town Planning

(Leicester, ), p. .

14

Meacham, ‘Raymond Unwin’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

for Letchworth Garden City. The separate parlour was, in their view, a waste of

valuable space in the crowded working-class home and a misguided ‘craving for

bourgeois respectability’ which should have no place in a modern democracy. A

single, large day-room, they suggested, better reflected the needs and living

arrangements of the worker’s family. Yet, to those with few resources to spare,

the parlour ‘though perhaps irrational, embodied, in an important, tangible form

a family’s ability to afford something beyond the minimum’.

15

As the first issue

of the Garden City journal put it, workmen and their wives ‘like the parlour and

they mean to have it’.

16

Unwin’s cottages may have been ‘good enough as

scenery’ but ‘they were not designed to suit the needs or prejudices of the

London workman’ who was coming to live and work there.

17

A comparable tension can be seen in the work of the Scottish planner, Patrick

Geddes.

18

Geddes was an idiosyncratic participant in the emerging field of town

planning, but his ideas on urban regeneration, or ‘civics’ as he termed it, simi-

larly inferred an ambiguous relationship between the planners and the planned.

His thinking on civics contained a vigorous conception of citizenship, extend-

ing beyond a shared knowledge of place, to entail a certain progressive dyna-

mism. As R. J. Halliday puts it, in Geddesian civics ‘the precondition of

citizenship was not just social awareness, but also the drastic and planned

improvement of both natural and urban environment’.

19

As a cog instrumental

in driving the whole machine, the citizen of Geddes’ prescription was to be an

active participant in the regenerative process. The citizens he saw in early twen-

tieth-century Edinburgh, however, displayed a marked apathy and a lack of care

or knowledge about their place. Nevertheless, Geddes was optimistic that this

could be reversed and, indeed, saw evidence of the beginnings of change in the

growing interest in civic societies and associations. Education, in his view, was

the key to unlocking this potential citizenship. A crucial part of the educational

experience would be the survey – to collect, marshal and exhibit data on all

aspects of life in the city and region. The sheer physical task of this work, it was

argued, would equip the citizens engaged on the project with a better under-

standing of the present and future needs of their place.

20

Children, in particular,

were targeted as the future citizens of the renascent town. Yet, education at a

higher level also had a role to play in Geddes’ scheme. The university, in partic-

ular, was regarded as an ideal focus for a regenerating city. In Edinburgh’s case,

the university, set in the midst of the old town, could help the city ‘become,

once again, an “Athens of the North”, as it had been in the late eighteenth

The planners and the public

15

Ibid., p. .

16

The Garden City, Oct. , not paginated, quoted in ibid., p. .

17

D. B. Cockerall, ‘A workshop in London and in Letchworth’, The City, Feb. , , quoted

in ibid., p. .

18

H. E. Meller, Patrick Geddes (London, ), p. , quoted in ibid.,p..

19

R. J. Halliday, ‘The sociological movement, the sociological society and the genesis of academic

sociology in Britain’, Sociological Review, new series, (), .

20

H. Meller, ed., The Ideal City (Leicester, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

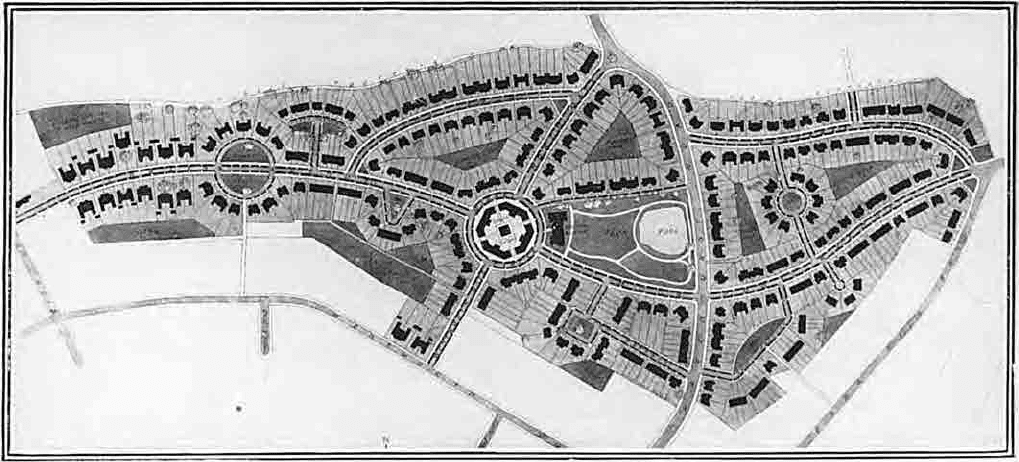

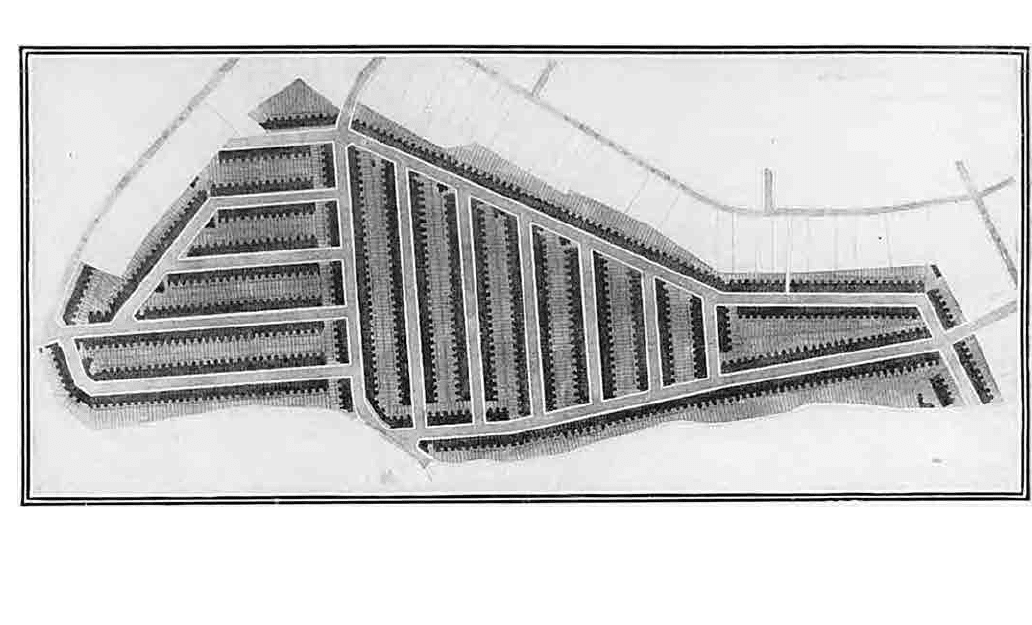

Figure . Plans comparing the layout of the estate built by Harborne Tenants Ltd in Birmingham at ten houses

per acre with hypothetical by-law layout at forty houses per acre

Site plan of Harborne tenants showing ten houses per acre

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Figure . (cont.) Ordinary type of site plan showing forty houses per acre

Source: L. P. Abercrombie, ‘Modern town planning in England: a comparative review of

“garden city” schemes in England, Part II’, Town Planning Review, (–), plate .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

century’.

21

Geddes’ project, therefore, exhibited a tension between the ideal of

the participatory citizen and direction from an elite body. He, typically, had a

term for this dualism, calling it ‘aristo-democracy’.

22

The problem with a latent

citizenship was that it required some precipitating factor; if this was to be edu-

cation, then who was to be the educator? Geddes spoke in terms of both self-

education by experience but also of the guiding light of the university and those,

like Geddes himself, who had already made the transition.

The tension between the aristocratic and the democratic was never fully

resolved by Geddes, nor, indeed, by Raymond Unwin.

23

Such dualism was not

uncommon in early twentieth-century social thought, and, in articulating it,

Geddes and Unwin were, as Standish Meacham has put it, ‘men of their time

and of their class, preaching along with other men and women to settlement

house audiences, in Fabian Society lectures, to University Extension and

Workers’ Educational Association students a particular brand of high-minded

culture which they believed would bring about the enlightenment of individu-

als and the creation of a right-minded democratic society’.

24

It was, moreover, a

durable legacy of the early planning movement. Later town planners, such as

Frederic Osborn, secretary of the Town and Country Planning Association

during the s, felt the potential contradiction just as keenly. Like Geddes

before him, Osborn seems to have been torn by his eagerness to involve the

public in town planning issues, and his awareness of the complexity and what he

regarded as the novelty of his subject. Frederic Osborn recognised that the public

had a right to express their preferences on the issue, and, indeed, welcomed this

form of decentralisation of initiative. For instance, he criticised the ‘Bloomsbury’

view of planning held by certain architects and aesthetes who dismissed the

Garden Cities of Letchworth and Welwyn, which Osborn saw as ‘the practical

exposition of the people’s wants’, as naive and gauche.

25

Yet, it is common to

find amongst Osborn’s correspondence an exasperation with the public. Writing

to Sir Montague Barlow on the proposals of the Uthwatt Committee on com-

pensation and betterment, he bemoaned the handicap imposed on the Town and

Country Planning Association ‘by the inability even of the select public to

understand the issues ...Itreally is too new a topic for the phase it has reached.

Gradually the powers are being built up, but it needs a much clearer and

stronger public opinion to get them used rightly.’

26

This knowledge gap between

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

21

Meller, ‘Urban renewal and citizenship’, .

22

P. Geddes, Dramatisations of History (Bombay, ), p. .

23

Meacham, ‘Raymond Unwin’, p. .

24

Ibid., pp. –.

25

Frederic Osborn Archive, Welwyn Garden City, B., letter from F. J. Osborn to C. B. Purdom,

June .

26

Frederic Osborn Archive, B., letter from F. J. Osborn to Sir Montague Barlow, July .

Ministry of Works and Planning, Interim and Final Reports of the Expert Committee on Compensation

and Betterment (Uthwatt), Cmds and (London, –).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

themselves, a highly trained minority, and the public, the bewildered lay major-

ity, continued to frustrate planners and architects into the post-war period.

If the intellectual basis of town planning in the early twentieth century implied

an ambivalent relationship between the planners and the public, the wider expe-

rience of town planning practice imposed further limitations on both the advo-

cacy and the achievement of a broad-based public involvement in the planning

process. From the very beginning the town planning movement was susceptible

to countervailing pressures, particularly from its financial and business backers.

Ebenezer Howard’s vision of a new ‘Garden City’, a self-contained entity

offering inhabitants a home, work and community amenities, was based on the

traditional symbol of community: the common entitlement to the land. Land

reform was, in Howard’s view, ‘the foundation on which all other reforms must

be built’.

27

Drawing heavily on the ideas of Henry George, an American advo-

cate of land reform whose criticism of landlordism was beginning to find favour

among British radical liberals, Howard envisaged his garden city as a vehicle for

returning to the community the ‘unearned increment’ in value which hitherto

fell to landlords in the form of rent.

28

As well as providing the financial basis for

the new city, this measure would, Howard argued, bring a qualitative social,

indeed, spiritual benefit, unifying the residents through a common interest.

29

Moreover, by giving residents a voice over land use, collective tenure was a mech-

anism of empowerment, offering protection from abuse by those with money.

30

This model for the ‘progressive reconstruction of capitalist society into an

infinity of co-operative commonwealths’ was to be given tangible form in the

first garden city at Letchworth. However, fundamental components of the plan

were frustrated by commercial realism and the need for pragmatism.

31

Howard’s

‘Georgite’ position on rent, for instance, was substantially altered in its transla-

tion into practice. The major objective of securing the increment in rent of

enhanced land value was not realised in Howard’s lifetime and only partially

afterwards. Commercial pragmatism diluted the ideal: leases of years carry-

ing only nominal ground rents had to be granted to industrialists in order to

induce them to bring their enterprises to the town, and rents of housing plots

could not be revised for years. Howard’s ideal of tenant self-government was

similarly compromised. This had been a key part of Raymond Unwin’s agenda

for the garden city – a part of his commitment to a diminution of ‘class’ distinc-

tions. Yet, as Meacham has noted, Letchworth’s governmental structure ‘did little

The planners and the public

27

R. Beevers, Garden Cities and New Towns (London, ), p. ; Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, p. .

See also E. Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrow (London, ).

28

For a discussion of the ideas of Henry George and the politics of the land question see A. Offer,

Property and Politics, – (Cambridge, ).

29

D. MacFadyen, ed., Sir Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City Movement (Manchester, ), p. .

30

E. Howard, ‘The land question at Letchworth, II’, The City, (), –.

31

Ibid., . See also E. Howard, ‘Our first Garden City’, St George’s Magazine ( July ), .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008