Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

to promote democratic participation across class lines’ and ‘the constantly intru-

sive presence of the Company in the affairs and decision-making of the com-

munity cast a paternalistic pall over the enterprise’.

32

A comparable tension also emerged at Hampstead Garden Suburb and in

other communities built on the co-partnership model during this period.

33

The

planners’ rhetoric stressed the social value of mixed neighbourhoods, but a con-

ception of ‘equality’ was noticeably absent. Instead, the dominant sentiments

were ‘fraternity’, ‘community’ and ‘fellowship’.

34

The actual involvement of

tenants in the running of the estates varied widely and, in the cases of the flagship

Ealing and Hampstead Tenants’ Societies, was very quickly diminished. The

Ealing society, whose initial management committee consisted of eleven

members, seven of whom were tenants, ‘had inherited the Tenant Co-partners’

rule of one person one vote’. However, this policy was changed between

and : the new constitution allowed voting by proxy and, crucially, awarded

‘an additional vote for every set of ten shares held’.

35

Interestingly, both at Ealing

and at Hampstead Garden Suburb, associations of tenants were formed in the

aftermath of this change ‘to advocate the return to those principles of true co-

partnership in housing, the wilful or careless neglect of which has been the fruit-

ful cause of much discontent among the Hampstead Tenant Shareholders, and

others’.

36

Other societies maintained a degree of tenant involvement at the level

of the management committee beyond the First World War, but it is clear that

pressure from commercial interests strained the relationship between non-tenant

members and tenants at various points during their history.

37

At a time when the questions of landownership and taxation had become

highly politicised, co-partnership housing and site planning tended to be seen as

a less controversial substitute for more elemental reform. In a similar way, the

Housing and Town Planning Act, while it reflected the contemporary res-

onance of the garden city idea, clearly stopped short of the movement’s ideals.

Under its provisions, local authorities were permitted to prepare town planning

schemes for land which was about to be developed or which ‘appeared likely

to be used for building purposes’, giving them power to control standards of

layout and impose conditions of development.

38

Existing built-up areas were

unaffected. Moreover, the municipalities were not given powers to acquire land

compulsorily for future town extension as many reformers, such as J. S.

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

32

Meacham, ‘Raymond Unwin’, p. .

33

J. Birchall, ‘Co-partnership housing and the garden city movement’, Planning Perspectives,

(), –; K. J. Skilleter, ‘The role of public utility societies in early British town planning

and housing reform, –’, Planning Perspectives, (), –; M. Miller and A. Gray,

Hampstead Garden Suburb (Chichester, ).

34

Birchall, ‘Co-partnership housing’, .

35

Ibid., .

36

Quoted in Skilleter, ‘The role of public utility societies’, .

37

Birchall, ‘Co-partnership housing’, –.

38

S. M. Gaskell, ‘“The suburb salubrious”: town planning in practice’, in Sutcliffe, ed., British Town

Planning, pp. , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Nettlefold and T. C. Horsfall, had urged.

39

As a result, planning was limited in

practice to suburban extension, and not the novel development envisaged by

Ebenezer Howard, and ‘as time passed, most observers came to agree that the

intricacies of the Act, which were designed mainly to protect private property,

were a serious obstacle’ to imaginative and community-orientated town

planning.

40

However, the dilution of the garden city model and the concurrent dwindling

of the co-partnership housing movement did not dissolve the town planning

movement’s exploration of the connection between tenure and citizen empow-

erment, for many planners and politicians now transferred their hopes to the

local authority, as the locus of community democracy. Labour and Fabian social-

ist reformers, whose numbers were beginning to swell the borough councils of

London and some other large urban centres, particularly supported the elected

local authority as the prime medium for a democratic housing and planning

policy. Raymond Unwin, himself a Fabian socialist, was in the forefront of this

shift, diverting his energies into the development of council housing during and

after the First World War. Yet, the interwar local government framework brought

its own constraints upon the development of a wide public involvement in the

planning process, not least of which was the failure to develop a comprehensive

framework for compensation and betterment.

Since the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, the problems of local govern-

ment finance, and the rating system in particular, had developed into an issue of

huge political importance.

41

From this was exacerbated by the rising social

demands placed upon local authorities and, as the post-war boom disintegrated

into slump and cutbacks, many found it increasingly difficult to meet the

demands made upon them. While social reconstruction, and particularly

housing and unemployment relief, remained at the forefront of political debate,

ratepayers’ associations and pressure from conservative municipal reform group-

ings seemingly put a ceiling on the raising of revenue from the traditional rates.

42

The local execution of town planning schemes was severely limited by this pres-

sure. While decentralisation of the working population into garden cities had

retained the imagination of the planners, and had gained the support of the

Labour party, both at national and local levels, the structure of local government

The planners and the public

39

G. E. Cherry, Cities and Plans (London, ), p. ; Nettlefold, Housing Policy; T. C. Horsfall,

The Improvement of the Dwellings and Surroundings of the People: The Example of Germany

(Manchester, ).

40

A. Sutcliffe, Towards the Planned City (Oxford, ), pp. , –; Gaskell, ‘“The suburb salu-

brious”’, .

41

J. Harris, ‘The transition to high politics in English social policy, –’, in M. Bentley and

J. Stevenson, eds., High and Low Politics in Modern Britain (Oxford, ), pp. –; Offer, Property

and Politics.

42

J. E. Cronin, The Politics of State Expansion:War, State and Society in Twentieth Century Britain (New

York, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

finance acted as a strong barrier to its practical implementation. Locating indus-

trial and retail activity within the city centre was a profitable strategy for local

authorities in terms of the collection of rates for its coffers. Suburban housing

development had brought similar benefits but with the greater restrictions of the

Ribbon Development Act this was an increasingly closed option. By way

of contrast, the building of out-county housing estates or satellite town devel-

opments would diminish the authorities’ rateable value. For many local author-

ities, therefore, the development of an innovative plan for decentralisation was,

virtually, financial folly. The issue was further compounded by the failure of

planning legislation to address successfully the problem of compensation and

betterment. The act had skirted around this issue, largely under pressure

from property interests, and while the Town Planning Act included provi-

sions for the recovery of betterment from owners whose property increased in

value as a result of a town planning scheme, it lacked strength to ensure imple-

mentation and was rarely effective. The result, Lewis Silkin, Labour’s town plan-

ning spokesman, argued in , was ‘the prevention of really bold and

imaginative schemes’with local authorities tending ‘to take the line of least resis-

tance and to prepare schemes which involve the minimum risk of compensa-

tion, generally based on the existing uses of land’.

43

Yet, while elements of the intellectual and political climate inhibited the artic-

ulation and development of a broadly participatory town planning process

during the interwar years, town planning thought undoubtedly retained an

interest in the potential social value of community-oriented planning. Much

town planning literature, for instance, continued to be informed by a rhetoric

of social integration and cooperation which stressed the importance of a vigor-

ous and participatory community life. This approach to town planning and

housing policy, indeed, seemed even more imperative in the light of the per-

ceived social and economic trends of the period, and in response to the specific

experiences of building during these years. The New Survey of London Life and

Labour, produced by Herbert Llewellyn Smith and his team of researchers from

, for example, assembled evidence of the continued segregation of the social

classes in London. While the middle classes were increasingly located in the bur-

geoning suburbs, the whole of London’s inner east was conversely characterised

by a high concentration of working-class families.

44

It was, moreover, a situation

which found echoes in other major urban locations, particularly in the Distressed

Areas, such as the north-east conurbation. Concern for the implications of this

unbalanced social structure was one of the ways in which the question of com-

munity continued to be examined in the interwar period. The development of

large, out-of-town housing estates, built primarily to resettle the slum-bound

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

43

L. Silkin, The Nation’s Land (London, ), p. .

44

H. Llewellyn Smith, ed., New Survey of London Life and Labour (London, –); J. A. Yelling,

Slums and Redevelopment (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

working classes, occasioned widespread criticism. The huge Dagenham and

Becontree estate on the east London and Essex border, for example, became an

emblem among planners and sociologists, representing the problems that could

result from a social housing policy which, however well meaning, failed to con-

front the complexities of building for a new community.

45

Social integration, it

was quickly realised, required more than the building of new self-contained set-

tlements. Several points were highlighted.

One area of interwar town planning thought which addressed the question of

the relationship between the built environment and the developing community,

as noted above, focused on the social mix of the community. During this period,

indeed, a balanced mix between the social classes became, for many planners and

social commentators, the defining characteristic of good town planning. At the

centre of their criticism lay the policy of rehousing the working population in

out-county housing estates. Instead of building stable and integrated commu-

nities, local authorities had created new zones of exclusion. Looking back from

, L. E. White felt that the one-income estate had become ‘the true habitat

for a rootless generation’.

46

Yet, while this remained a popular view among plan-

ners and politicians, informing new towns and housing policy into the post-war

period, a number of commentators preferred to stress the advantages of social

homogeneity, often advocating the redevelopment of inner-city areas as an alter-

native policy.

47

This, they argued, was more in line with residents’ wishes. While

the physical infrastructure of many inner-city areas was admittedly deplorable, res-

idents found compensation in a positive social life and network. Mrs Bentwick’s

study of Bermondsey for the London County Council noted that although people

liked cottage homes in preference to flats, they nevertheless preferred flats in

Bermondsey to cottages elsewhere. ‘One reason for the happy atmosphere of the

Borough’, she argued, ‘is the fact that per cent of its population is working class.

It is the mixed boroughs like Kensington and Wandsworth which lack this extreme

civic pride and consciousness and sense of unity.’

48

At the heart of both view-

points lay a belief that good town planning required a positive interaction between

the planners and the public which they served. Yet, neither had developed a coher-

ent argument on how this might realistically be achieved.

A number of commentaries on town planning in the interwar years, however,

did stress the importance of understanding both the existing life and the future

hopes of incoming residents. For example, in their evaluation of the housing and

planning policy of the corporation of Bristol, Rosamund Jevons and John Madge

The planners and the public

45

For the development of Dagenham and Becontree, see A. Olechnowicz, Working-Class Housing

in England Between the Wars (Oxford, ).

46

L. E. White, Community or Chaos? (London, ), p. .

47

Yelling, Slums and Redevelopment, pp. –.

48

Greater London Record Office, AR/TP//. Report on Bermondsey, May , quoted in

Yelling, Slums and Redevelopment, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

noted the failure of many planners fully to ‘appreciate the implications of living

in central areas’ before building the new estates on the outskirts of the city:

A knowledge of the institutions upon which urban populations rely for amuse-

ments, for convenience and in time of need, is of primary importance as a guide

to the amenities required in new neighbourhoods. This knowledge gives an insight

into the nature of an environment which appeals to the tastes and imagination of

town people; it is up to the planners to retain the advantages of this environment

and at the same time to eliminate its faults. Prejudice against urbanism as such is

not an attitude calculated to lead to organic planning.

49

Nevertheless, while Jevons and Madge seem to have recognised the importance

of prior and on-going consultation between planners and residents, they, like

many other commentators, did not press this argument to its logical conclusion:

the best means to achieve such a confluence of aims in practice, for instance,

were barely articulated.

A more developed sense of the interaction between the emerging commu-

nity and the built environment perhaps surfaced in the continuing interest in the

social function of communal buildings and institutions. Throughout the s

the New Estates Community Committee of the voluntary organisation the

National Council of Social Services (NCSS) pressed the case for community

associations and community centres.

50

These local groups and buildings, it

argued, could play a crucial role in breaking down the barriers of isolation

which, it was felt, were an all too common feature of the new housing estates.

The lack of an established tradition of community activity within the new estates

was problematic, but also provided a positive opportunity and a challenge ‘to

those who live there to build up a community life that is something different

from the life of the old towns’. The absence of vested interests and competing

organisations, indeed, could be valuable, creating ‘greater opportunity for self-

development’ and providing ‘a clear field on which to plan what the citizens

themselves desire to realise’.

51

Yet, as Jevons and Madge noted, the resident pop-

ulation needed to develop its own sense of the value of these institutions and

buildings if a genuine sense of community was to develop. While the local

authority had responsibility for providing communal buildings, the balance of

evidence from Bristol, they suggested, was ‘against continued municipal

control’. Instead, the local community should be encouraged to take over their

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

49

R. Jevons and J. Madge, Housing Estates (Bristol, ), p. .

50

The New Estates Community Committee of the NCSS was established in . It was represen-

tative of the NCSS, the British Association of Residential Settlements and the Educational

Settlements’ Association. It was chaired by Ernest Barker, theorist and writer on English political

thought (and the first Professor of Political Science at Cambridge) and an active advocate of com-

munity regeneration. On the National Council of Social Service see M. Brasnett, Voluntary Social

Action:A History of the National Council of Social Service, – (London, ). See also R. Clarke,

ed., Enterprising Neighbours: The Development of the Community Association Movement in Britain

(London, ). On Barker, see J. Stapleton, Englishness and the Study of Politics (Cambridge, ).

51

Anon., ‘Community work in the new housing estates’, Social Service Review, (), .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

management as soon as possible: ‘People dislike to think that some paternal

outside authority is trying to teach them how to be pally when mutual help is a

virtue which they were practising generations before new estates were planned.

In the long run, inhabitants alone can build up their own community life.’

52

The

integrative role and democratic potential of community-run institutions contin-

ued to interest planners after the Second World War. Not only did the NCSS

maintain its sponsorship of the Community Association and Centre movement

into the post-war period, but neighbourhood plans, for both new and existing

towns, often incorporated designs for locally managed communal buildings and

projects, such as community, arts and health centres. The Second World War and

the need for large-scale reconstruction of the urban environment, indeed, forced

planners and politicians to address the nature of their relationship with the public

under whom they served more thoroughly than ever before.

The planners and the public

52

Jevons and Madge, Housing Estates, p. .

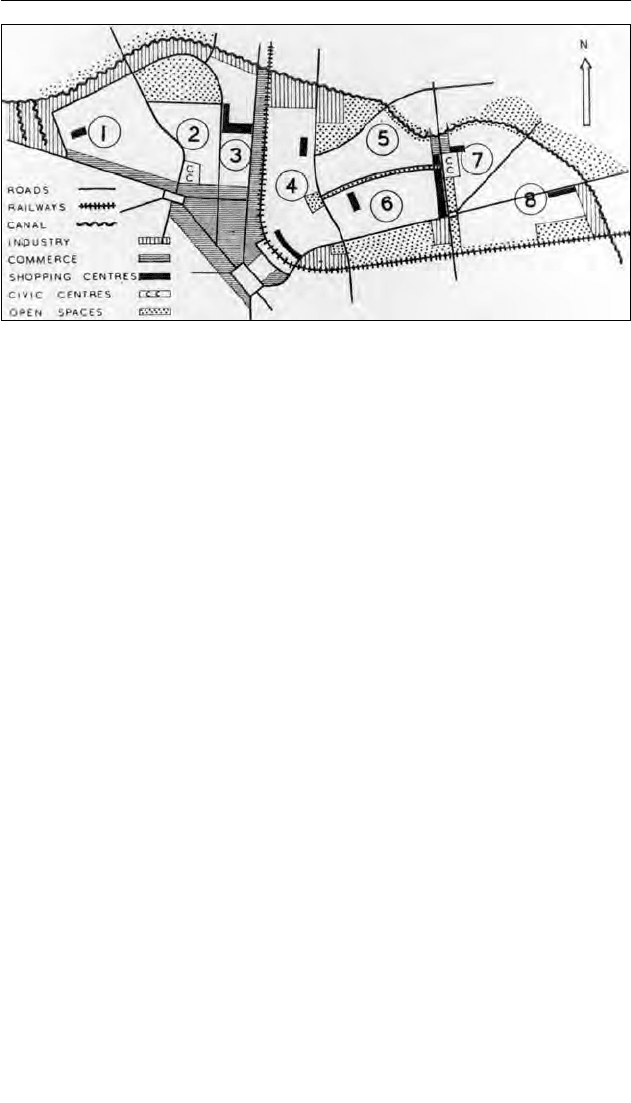

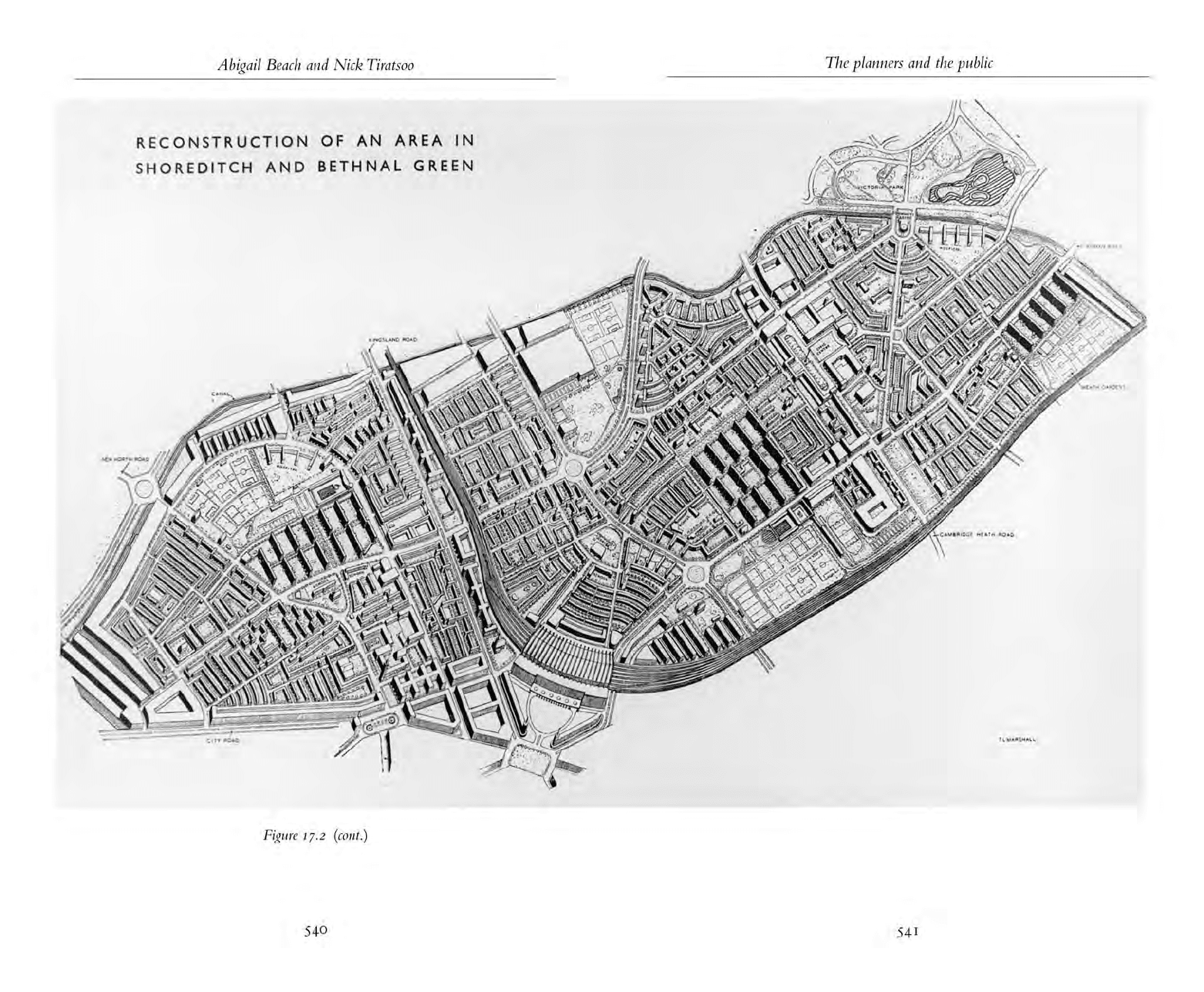

Figure . Suggested redevelopment of an area of acres in East London

‘As the key plan and axonometric view show, the area comprises the two

communities of Shoreditch and Bethnal Green, which are built up of three and

five neighbourhood units respectively; each unit has its own local shopping and

community centre. The populations of the units vary between , and

, and are housed at a net density of persons to the acre. New open

space is shown provided to bring the standard up to acres per , persons.

To achieve this layout, decentralisation of a proportion of the population

will be necessary. acres of new open space are shown in the scheme,

which, together with the existing acres and an allowance of acres of the

adjoining open spaces (Victoria Park and proposed new parks) give a total of

acres. The axonometric view shows the character of development at the

density and the proportion of flats and houses that it is possible to provide.

The proposals embody the character and vitality of a new East End.’

Source: County of London Plan, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

The planners and the public

RECONSTRUCTION

OF AN

AREA

IN

SHOREDITCH

AND BETHNAL GREEN

m

•

Figure

17.2 (writ.)

540

541

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Labour’s victory in the general election certainly promised a new dawn

for town planning. The party had long-standing links with the planning move-

ment and shared many of its broad goals. Labour believed that British cities were

technically dysfunctional. Many suffered from congestion and were poorly

zoned. Most, too, had failed their working-class populations, as the numerous

slum districts graphically demonstrated. More fundamentally, the pattern of

urban living seemed to discourage community and good fellowship, ideals that

were at the very heart of Labour’s socialism.

53

Aneurin Bevan, Minister of

Health in the new government, denounced the social segregation that was

apparent in cities and argued that people must be brought together. There was

great merit, he believed, in the old village pattern, where ‘the doctor could

reside benignly with his patient in the same street’.

54

In this view, there was no

better way of reintegrating citizens than involving them in decision making

about their own localities.

During the next few years, Labour did much to act upon such ideas. The

central piece of fresh legislation was the Town and Country Planning Act.

This rationalised the number of planning authorities, devolving responsibility on

to county boroughs or county councils, and instructed the new bodies to prepare

development plans for their localities. It also introduced complex procedures for

dealing with compensation and betterment, allowing national resources to be

used as necessary in the solution of local ownership problems.

This legislation clearly meant that civil servants, councillors and professional

planners would play new and enhanced roles, but it also allowed for a consider-

able measure of public input. Planning authorities were instructed to consult as

widely as possible when constructing their plans. Moreover, ordinary citizens

had the right to challenge the final recommendations, through an appeals pro-

cedure before an inspector at a public hearing. The objective was to strike a

balance between the requirement for technical expertise in planning and the

interests of the individual.

Other policies reinforced the drive towards community and participation.

Labour was formally committed to building new housing estates as neighbour-

hood units on the lines advocated by Sir Charles Reilly, Lever Professor of

Design at Liverpool University, since it was believed that these would promote

social intercourse and intelligent debate (in Reilly’s words, ‘the advantages of a

residential university’).

55

It also wanted to bridge the gap between those in town

halls and their constituents. A Consultative Committee on Publicity for Local

Government was created in to review procedures and make recommenda-

tions. The central overall aim, as the leader of Coventry’s authority explained at

the end of the war, was to perfect ‘a new democratic technique’ which would

Abigail Beach and Nick Tiratsoo

53

S. Fielding et al., ‘England Arise!’ The Labour Party and Popular Politics in s Britain (Manchester,

).

54

Quoted in Architects’ Journal, June .

55

Tribune, Feb. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

‘make the citizen conscious of the vital part, the living part he [sic] has to play

. . . in a real democracy’.

56

What did these various measures achieve? The act’s financial measures

remained controversial but its appeals procedure proved something of a success.

The Ministry responsible, it was noted, seemed to be making a real effort at

openness. An American academic visitor reported: ‘Inspectors . . . permit gra-

tuitous expressions of opinion. Objections to evidence on technical grounds are

rather unpopular. Letters and petitions are admitted without formal identifica-

tion and substantial latitude is permitted in cross-examination. Expenses of

hearing are nominal, making redress practically available to all.’

57

Furthermore,

it was obvious that complaints were receiving a fair hearing. As Table .

illustrates, successful appeals always made up at least per cent of the cases

adjudicated upon.

On the other hand, progress elsewhere was far less marked. Few councils were

able even to envisage building neighbourhood units because of the stringent

financial controls which were imposed on them by Whitehall, especially after

. Nor did the drive for local publicity gain any great momentum. Some

councils opened information offices, while others held planning or reconstruc-

tion exhibitions, but they were in a minority. Many felt nothing new was

required. One town clerk told the Consultative Committee ‘that news travelled

so fast in his area that there was little need of any channel of communication

with the public’.

58

Most worrying for Labour, finally, was the widely shared per-

ception that few members of the public were becoming in any way ‘planning

minded’. As the prominent London School of Economics (LSE) political scien-

tist W. A. Robson argued in , planning seemed to have become becalmed

The planners and the public

56

Coventry Evening Telegraph, June .

57

R. Vance Presthus, ‘British town and country planning: local participation’, American Political

Science Review, (), –.

58

H. J. Boyden, Councils and their Public (London, ), p. .

Table . Appeals under the Town and Country Planning Act –

Cases disposed of , , , ,

Appeals allowed , , , ,

Appeals dismissed , , , ,

Appeals withdrawn , , , ,

Source: Cmd , Ministry of Local Government and Planning, Town and Country

Planning – (April ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008