Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of avoiding both the solely structural, and the solely cultural, approaches to the

vexed but crucial subject of class.

4

Yet this chapter cannot be a straightforward survey. For a start, rather than

assume the impact of the middle class on urban Britain, it is necessary to dem-

onstrate how far and how this influence was sustained – in relation both to the

surprisingly influential aristocracy and to the increasingly well-organised

working class.

5

This demands particular care because historical research on the

middle class has concentrated on the period prior to , after which significant

changes occurred – notably accelerating suburbanisation – in the structure and

nature of urbanisation. Moreover, the chapter must deal not only with issues of

social structure, broadly defined, but also with the roles played by middle-class

individuals and groups in the broader economic, social and political life of urban

Britain.

6

To a significant extent, therefore, this must be a study of elites as well

as of class.

7

Before going further it is appropriate to define ‘class’ in general and ‘middle

class’ in particular. In this study, a class is a group which shares a similar economic

situation, level of prestige and eligibility for key positions: it is not assumed that

such a group thinks alike or acts coherently.

8

This chapter approaches the middle

class broadly, including all employers, all non-manual employees and all (apart

from the landed aristocracy and gentry) people supported by independent

income. As this middle class encompassed very considerable contrasts in

resources, the study often subdivides the group into upper, middle and lower

strata; this tripartite division – similar to that adopted in the s by R. D.

Baxter and echoed by many other contemporary commentators – avoids the

inordinately diverse lower stratum of twofold division schemes.

9

Other sorts of

subdivision – by occupational group, and by religious and political affiliation, for

example – are also adopted. In our own time, admittedly, ‘middle class’ has

Richard Trainor

4

M. Savage, ‘Urban history and social class: two paradigms’, UH, (), , . For a measured

defence of class analysis see Kidd and Nicholls, Making, introduction, pp. xvi–xxiii.

5

Savage, ‘Urban history’, pp. –; M. Savage, The Dynamics of Working-Class Politics (Cambridge,

); D. Cannadine, Lords and Landlords (Leicester, ).

6

However, there is less coverage here of economic and cultural issues because of the chapters in this

volume by Reeder and Rodger, and by Morris, respectively.

7

To avoid repetition with the chapter on urban government the emphasis here falls on middle-class

elites as a whole and, more particularly, on their involvements in secular and religious voluntary

societies. Elites are primarily defined as those who held leadership positions in the major institu-

tions. For an explanation of this approach – which does not take for granted either the agendas of

these institutions or the influence of their leaders – see Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –.

8

For a detailed explanation of this approach see ibid., pp. –. Cf. John Scott, Stratification and

Power: Structures of Class, Status and Command (Cambridge, ).

9

R. D. Baxter, National Income:The UK (London, ), p. , who identifies the divisions with

income ranges: up to £, £–£, and (subdivided at £,) £,+. For a multidi-

mensional approach adapted to regional variations, see Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

become a rather vague and contested term.

10

Also, in the Victorian period as

now, such a term was at least as much a cultural construct as a neutral tool of

social classification. Yet in the early nineteenth century, ‘contemporaries were

quite clear . . . what it meant . . . to speak of working-class and middle class’.

11

The term broadened during the Victorian period to cover the range of occupa-

tions intended here. During the first half of the twentieth century and beyond,

its meaning – both in popular and in scholarly discourse – remained stable and,

for most observers, unproblematical.

12

In dealing with the urban middle class since the mid-nineteenth century the

chapter has to cope with the conflicting views of historians, many of whom –

with important exceptions relating to the early Victorian decades and, through-

out the period, to London – have tended during the last twenty-five years to

emphasise division and weakness rather than coherence and strength. There is

general agreement that, between the late eighteenth century and about , the

middle class developed rapidly within, and exercised considerable influence over,

British towns, especially in provincial industrial areas. This was the middle class

which played important roles in the repeal of the corn laws, the reform of

municipal corporations and the rise of a network of thriving urban institutions

with prominent roles for prosperous businessmen.

13

Yet some historians believe

that, even in this part of the period and in the local arena, the influence of

middle-class leaders was limited by internal divisions, the impact of landed elites

and the intractability of the working class.

14

From this point of view, on the

national stage middle-class impact was even more constrained – not only by the

persisting power of traditional governing elites but also by a deep division

between the provincial urban middle class, on the one hand, and its relatively

larger, better-off equivalent in London and environs, on the other.

15

There is

The middle class

10

For a scholarly attempt to unravel these complexities, see T. Butler and M. Savage, eds., Social

Change and the Middle Classes (London, ).

11

E. Royle, Modern Britain: A Social History – (London, ), p. . For the process by

which the term ‘middle class’ was constructed see D. Wahrman, Imagining the Middle Class:The

Political Representation of Class in Britain, c. – (Cambridge, ).

12

Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –. Cf. R. Lewis and A. Maude, The English Middle Classes

(London, ); I. Bradley, The English Middle Classes are Alive and Kicking (London, ).

13

See, for example, the works cited in n. above; D. Fraser, Urban Politics in Victorian England

(Leicester, ); D. Fraser, ed., Municipal Reform and the Industrial City (Leicester, ).

14

See in particular J. A. Garrard, Leadership and Power in Victorian Industrial Towns –

(Manchester, ); F. M. L. Thompson, ‘Social control in Victorian Britain’, Ec.HR, nd series,

(), –.

15

The most influential works are those of W. D. Rubinstein, particularly: ‘The Victorian middle

classes: wealth, occupation, and geography’, Ec.HR, nd series, (), –; ‘Wealth, elites

and the class structure of modern Britain’, P&P, (), –; Men of Property (London,

); Elites and the Wealthy in Modern British History (Brighton, ). Cf. also M. J. Wiener,

English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

even more support from historians for the view that, from the late nineteenth

century, urban provincial middle-class elites (within which participation by the

wealthy was already falling) faced increasing incursions in the local arena from

central government and an insurgent working class. Moreover, during the same

period the national position of the provincial urban middle class – more depen-

dent on industry and less closely tied to finance, commerce, land and the pro-

fessions than was its metropolitan equivalent

16

– may have declined even more

rapidly. Especially after , as British industry lost momentum (especially in

the North and in Scotland), and as London and its dynamic suburbs appeared

increasingly dominant in the nation’s political, economic, social and cultural life,

provincial towns and cities evidently lost many of their middle-class inhabitants,

especially from the upper strata. In many localities, it would seem, lower-middle-

class worthies and the representatives of organised labour subsequently battled

for the scraps of a once vibrant urban culture. By the s, apparently, with the

partial exception of London, Britain’s towns and cities were bereft of effective

middle-class influence, except in narrowly economic terms.

17

Some studies have cast doubt, for the pre- period, on the proposition that

a professionally, financially and commercially focused middle class centred in the

South-East of England overshadowed an industrially centred middle class based

in the Midlands, the North and Scotland.

18

But this is still contested terrain.

19

Given the attention devoted to these issues during the last quarter century, there

is need for an analysis of the middle class between the mid-nineteenth and the

Richard Trainor

16

See, for example, C. H. Lee, ‘The service sector, regional specialisation and economic growth in

the Victorian economy’, Journal of Historical Geography, (), –; G. Ingham, Capitalism

Divided? (Basingstoke, ). On persisting divisions between professionals and others in the

middle class, see M. Savage et al., Property, Bureaucracy and Culture (London, ), pp. – and

passim.

17

For these arguments see, for example, H. J. Dyos, ‘Greater and Greater London: notes on metrop-

olis and provinces in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’, in J. S. Bromley and E. H. Kossman,

eds., Britain and the Netherlands, vol. : Metropolis, Dominion and Province (The Hague, ),

pp. –; A. A. Jackson, The Middle Classes, – (Nairn, ), pp. , , –, ;

P. L. Garside, ‘London and the Home Counties’, in F. M. L. Thompson, ed., The Cambridge Social

History of Britain, –, vol. , Regions and Communities, pp. , –, , –; B.

Robson, ‘Coming full circle: London versus the rest, –’, in G. Gordon, ed., Regional

Cities in the UK, – (London, ), pp. –; W. D. Rubinstein, ‘Britain’s elites in the

interwar period, –’, in Kidd and Nicholls, eds., Making, pp. –.

18

See, for example, Berghoff, ‘Regional variations in provincial business biography: the case of

Birmingham, Bristol and Manchester, –’, Business History, (), –; M. J.

Daunton, ‘Gentlemanly capitalism and British industry –’, P&P, (), –; S.

Gunn, ‘The failure of the Victorian middle class: a critique’, in J. Woolf and J. Seed, eds., The

Culture of Capital (Manchester, ), pp. –; R. H. Trainor, ‘Urban elites in Victorian

Britain’, UHY (), –; R. H. Trainor, ‘The elite’ (hereafter referred to as ‘Glasgow’s elite’),

in Fraser and Maver, eds., Glasgow

, , pp. –.

19

For a sophisticated restatement of the ‘overshadowing’ thesis see F. M. L. Thompson, ‘Town and

city’, in Thompson, ed., Cambridge Social History, , –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

mid-twentieth centuries which analyses the differences – and similarities –

between the roles it played in various types of towns and cities.

20

(ii) ,

The first stage in this process is to examine the relative size, the occupational

structure and the internal stratification of the urban middle class, paying partic-

ular attention to variations between the urban provinces and the urban South-

East. Analysis of occupational patterns significantly and increasingly qualifies,

though it does not eliminate, the impression of London’s superior position

within the later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century middle class. More pos-

itively, in combination with various types of qualitative evidence the occupa-

tional data demonstrate the existence of a diverse and increasingly numerous

middle class in the urban provinces, especially but not only in key regional

centres such as Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and Glasgow.

While occupation is an imperfect proxy for class it provides the single best clue

to overall social position, not least because it is closely associated with prestige.

21

Thus, significant differences in average earnings correspond to the various ‘occu-

pational classes’ based on the census. Also, by the s a town’s occupationally

derived social class composition correlated closely with many of its other social

characteristics.

22

Still, it is difficult to infer social stratification from occupational

groups in the published census. The socially heterogeneous categories changed

between censuses, and only from did they even attempt to map social

inequality. Similarly, only in the twentieth century do the figures for the propor-

tion of females employed in middle-class occupations become at all meaningful.

There is also a distortion caused by the fact that the census groups which are very

largely middle class tend to be white collar, thereby excluding owners of work-

shops and small factories.

23

None the less, these problems do not have a consis-

tent bias, with regard either to the overall size of the middle class or to its regional

distribution. Also, when used cautiously – for example, by restricting intercen-

sal comparisons to periods when there was much consistency of classification

24

The middle class

20

In doing so the chapter will pay less attention to country and market towns, and to London,

because of the chapters in this volume devoted to these subjects.

21

W. A. Armstrong, ‘The use of information about occupation’, in E. A. Wrigley, ed., Nineteenth-

Century Society (Cambridge, ), pp. – and passim.

22

G. Routh, Occupation and Pay in Great Britain – (Cambridge, ), pp. –; C. A. Moser

and W. Scott, British Towns (Edinburgh, ), pp. , –, –.

23

D. C. Marsh, The Changing Social Structure of England and Wales – (London, edn), pp.

, ; R. Lawton, ‘Census data for urban areas’, in R. Lawton, ed., The Census and Social

Structure (London, ), pp. –. Cf. E. Higgs, A Clearer Sense of the Census (London, c. ).

24

Cf. Marsh, Social Structure, p. ; Armstrong, ‘Use of information’, p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

– such information can provide useful albeit rough indicators of social structure.

These measures are especially helpful for the twentieth century, for which more

socially precise information derived from the manuscript census is, with rare

exceptions, not yet available.

It is appropriate to examine first the occupation orders – i.e. the simple aggre-

gations of occupational groups – keeping in mind the consensus that the middle-

class proportion of the total population expanded gradually but steadily during

the period –, especially in lower-middle-class occupations, rising from

perhaps a sixth to about a quarter.

25

We should also be aware that estimates based

on the proportion of the adult male population possessing the borough parlia-

mentary franchise between and suggest that the middle class consti-

tuted a significant minority in all types of town but that the proportion varied

widely, from as low as per cent in industrial areas to more than per cent in

cathedral and county towns.

26

In – using the four categories most likely to contain middle-class indi-

viduals

27

– London led all the boroughs (except Portsmouth) in England and

Wales with . per cent of its occupied males. At the other extreme, predict-

ably, were industrial towns such as Oldham (. per cent) and Merthyr Tydfil

(. per cent). Yet relatively high results, while found in south-eastern citadels

such as Cambridge (. per cent) and Chichester (. per cent), were not

confined to that region, as the cathedral city examples of Exeter (. per cent),

Lincoln (. per cent), and Durham (. per cent) indicate. More surprisingly,

given the bias of these measures against areas with large amounts of industrial

enterprise, there were significant figures for Liverpool (. per cent),

Manchester and Salford (. per cent), Newcastle-upon-Tyne (. per cent),

Nottingham (. per cent) and Birmingham (. per cent). Similar interurban

patterns emerge from another early Victorian measure: the number of income

taxpayers (at a time when vulnerability to income tax roughly coincided with

middle-class status) in . Even allowing for likely biases toward the metrop-

olis in the collection of income tax (see below, p. ), London’s figure of .

per cent confirms its position as the mid-nineteenth century urban locality with

Richard Trainor

25

G. Best, Mid-Victorian Britain –, rev. edn (St Albans, ), pp. –; A. L. Bowley, Wages

and Income in the United Kingdom since (Cambridge, ), pp. –; C. Erickson, British

Industrialists (Cambridge, ), pp. –; Royle, Modern Britain, pp. –, drawing on J. A.

Banks, ‘The social structure of nineteenth century England as seen through the census’, in

Lawton, ed., Census, pp. , ; J. Burnett, A Social History of Housing, –, nd edn

(London, ), p. .

26

Morris, ‘The middle class and British towns and cities’, pp. –. Cf. Trainor, Black Country

Elites, p. .

27

I = General and Local Government; III = Learned Professions (and their immediate subordinates);

IV=Literature, Fine Arts and the Sciences; VII = Buyers, Lenders etc. of Money, Houses and

Goods. Even taken together, these categories significantly understate middle-class numbers by

missing, for example, managers and clerks employed in industry.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

the greatest proportion of middle-class males. However, while cathedral, county

and market towns come next in the pecking order – Gloucester has . per

cent, Buckingham . per cent and Banbury . per cent, for example –

major provincial cities such as Bristol (. per cent), Liverpool (. per

cent), Manchester (. per cent) and Birmingham (. per cent) also have

substantial proportions. As in the census, it is the overwhelmingly industrial

towns (Blackburn at . per cent and Leicester at . per cent, for example),

which come last – and even there a far from negligible proportion and number

of middle-class individuals are indicated.

28

Similar results emerge from analyses of occupation orders I (Government), III

(Professions and their Subordinates) and V (Commercial and Clerical) from the

censuses of to inclusive. Many south-eastern towns had clear leads

over their counterparts drawn from other regions. Thus London and Croydon

(. per cent and . per cent in , respectively) – joined by Middlesex

(at . per cent) in – had the largest proportions, and industrial towns

such as Burnley and Walsall (both at . per cent in ; . per cent and

. per cent respectively in ) had among the lowest. Yet each of these lists

also shows the major provincial English cities to have had substantial proportions

of their male workforces in these key middle-class categories. Manchester and

Liverpool, for example, already at per cent in , moved up in to .

per cent, to the range – per cent in and to – per cent in .

These results, reflecting the very considerable white-collar presence in the indus-

tries as well as the commercial trades of these cities, indicate that in the prov-

inces significant middle-class percentages were not confined either to the more

genteel cities like Bristol (. per cent in , . per cent in ) and

Norwich (. per cent in , . per cent in ) or to county towns such

as Bath and York (. per cent and . per cent respectively in ). It is

also worth noting the high ratings for Midland and northern towns like

Birkenhead and Southport (. per cent and . per cent respectively in

) which had substantial middle-class suburban populations. Scottish towns,

too, scored well on such measures.

29

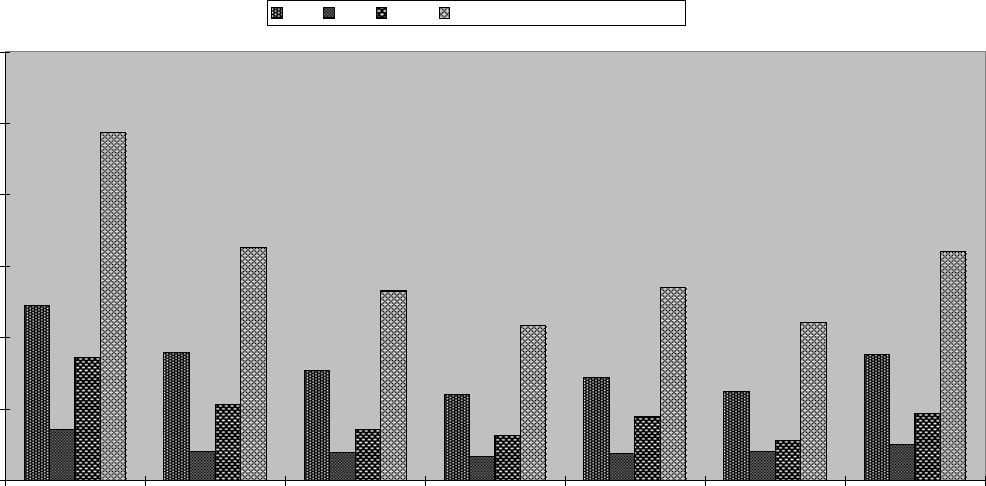

Occupation orders, analysed by conurbation, from the and cen-

suses, produce similar conclusions. In , for example, Greater London easily

led the male figures for commercial, professional and clerical occupations (Figure

.). Yet in none of the key provincial urban areas were the individual or com-

bined totals for these categories less than substantial. The results for are

The middle class

28

See W. D. Rubinstein, ‘The size and distribution of the English middle classes in ’, HR,

(), –, with conclusions differing in emphasis to the interpretation offered here.

29

Morgan and Trainor, ‘Dominant classes’, pp. –, give even higher figures for Scotland, having

taken detailed middle-class dealing and industrial occupations out of other orders. A number of

cities absorbed previously separate middle-class areas in the thirty years prior to , as

Birmingham did Handsworth and Glasgow did Hillhead.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

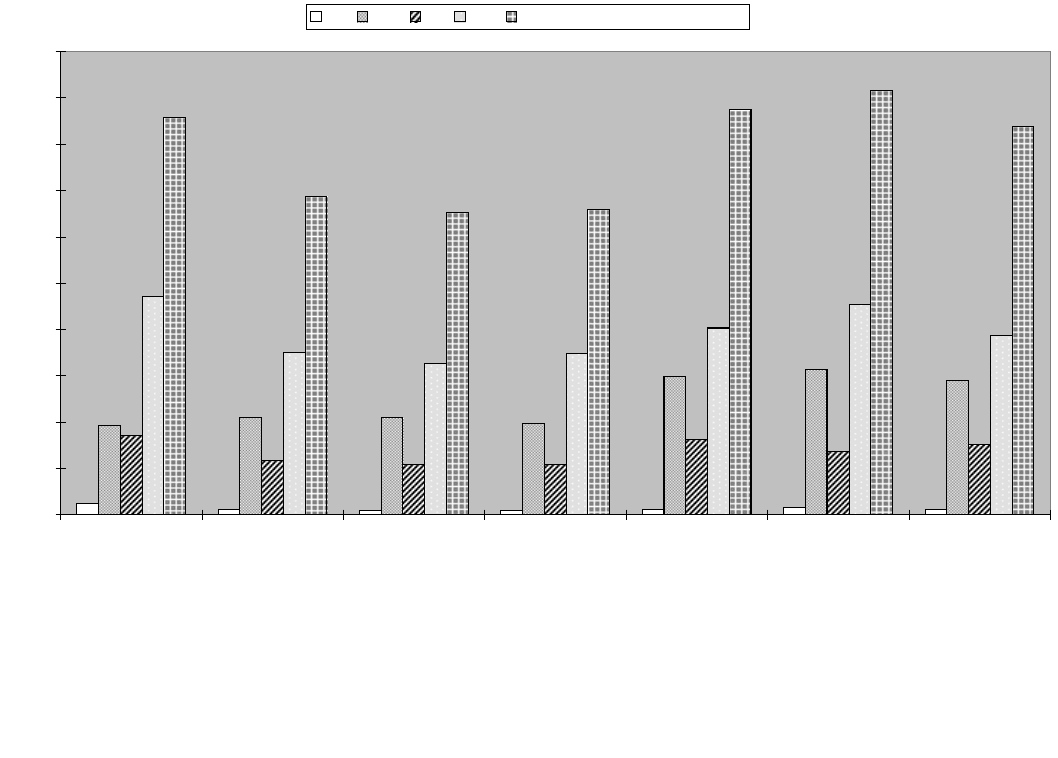

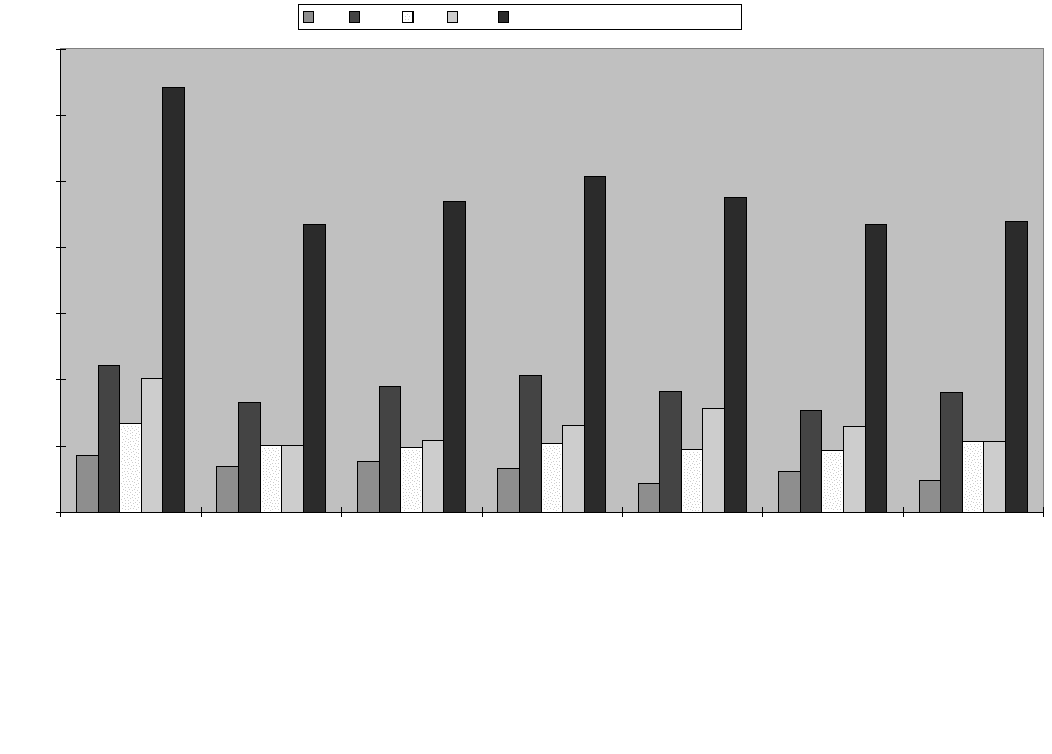

comparable, though Figure . shows little London advantage in female middle-

class employment, and Figure . suggests some contraction of London’s male

middle-class advantage compared to thirty years before – perhaps because in an

increasingly white-collar and professional society older occupational contrasts

between the Metropolis and the provinces had begun to fade.

Even greater parity between London and provincial cities emerges when the

focus shifts (in Figure .) to the socio-economic groups of the census, a

measure of households rather than of individual salary earners, and one which

includes many of the managers, employers and shopkeepers missed by the occu-

pation orders’emphasis on white-collar groups. London’s lead remained substan-

tial, but the major English provincial conurbations, and Central Clydeside,

showed significant middle-class proportions as well. An even flatter set of overall

comparisons emerges in Figure . which depicts the Registrar General’s

troublesome five-class scheme. This measure supports the case for the significant

size of the provincial middle class but to a misleadingly great degree due to the

notoriously bloated class III, which includes a significant proportion of manual

workers.

30

More indicative are statistics (not given here) concerning the propor-

tions of the occupied workforce in middle-class status aggregates such as employ-

ers and managers: these too indicate less of a lead for London than do the

pre- figures for occupation orders.

What these various measures suggest, then, is that significant and rising pro-

portions of the workforces, and thus of the total populations, of major provin-

cial urban areas – and even of many individual provincial towns – were middle

class. Also, the gap between the relative sizes of the provincial and metropolitan

middle classes, which may have been diminishing as early as the turn of the

century, was contracting by the early s.

Given London’s huge size compared to other British cities, in terms of abso-

lute numbers of middle-class inhabitants the capital was even more firmly in the

lead. But in this respect, too, provincial strength was considerable. Thus Glasgow,

for example, had over , men and women in commercial occupations in

. Manchester had more than , and Birmingham more than ,

accountants in , when Glasgow and Edinburgh combined had just short of

a thousand physicians, surgeons and general practitioners and more than ,

clerks. By the provincial numbers in such occupations were much greater.

South-east Lancashire then boasted more than , clerks and typists, while

Bristol had more than ,.

31

Provincial cities and towns shared in the rise in

Richard Trainor

30

See Armstrong, ‘Use of information’, p. ; and A. M. Carr-Saunders et al., Survey of Social

Conditions in England and Wales . . . (Oxford, ), pp. –. Concentrating on the propor-

tions of classes I and II shows a significant, but not massive, lead for London – a conclusion sup-

ported, for the South-East as a whole, by Moser and Scott’s analysis of English and Welsh towns

with at least , inhabitants (British Towns, Map ).

31

Published census; Morgan and Trainor, ‘Dominant classes’, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0.00

5.00

10.00

15.00

20.00

25.00

30.00

Greater

London

Lancashire Yorkshire, West

Riding and

city of York

North-East

coast

Birmingham

and district

South

Wales

ENGLAND

and WALES

XXIII XXV

XXVIII TOTAL OF XXIII, XXV and XXVIII

Figure . Occupation Orders XXIII, XXV and XXVIII, males aged twelve and over, as percentage of total occupied, in six

mainly urban areas of England and Wales, plus England and Wales as a whole,

XXIII⫽ commerce, finance and insurance (excluding clerks)

XXV⫽ professional occupations (excluding clerks)

XXVIII⫽ clerks, typists, etc.

Source: census for .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0.00

5.00

10.00

15.00

20.00

25.00

30.00

35.00

40.00

45.00

50.00

XVI XVIII XIX XXIII Total of XVI, XVIII, XIX and XXIII

Greater

London

West

Midlands

West

Yorkshire

South-east

Lancashire

Merseyside Tyneside

Central

Clydeside

Figure . Occupation Orders XVI, XVIII, XIX and XXIII, females aged fifteen and over, as percentage of total occupied, in

conurbations,

XVI⫽ administrators, directors, managers (not elsewhere specified)

XVIII⫽ commercial, finance and insurance occupations (excluding clerical staff )

XIX⫽ professional and technical occupations (excluding clerical staff )

XXIII⫽ clerks, typists, etc.

Source: census for .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0.00

5.00

10.00

15.00

20.00

25.00

30.00

35.00

XVI XVIII XIX XXIII Total of XVI, XVIII, XIX and XXIII

Greater

London

West

Midlands

West

Yorkshire

South-east

Lancashire

Merseyside Tyneside

Central

Clydeside

Figure . Occupation Orders XVI, XVIII, XIX and XXIII, males aged fifteen and over, as percentage of total occupied, in

conurbations,

XVI⫽ administrators, directors, managers (not elsewhere specified)

XVIII⫽ commercial, finance and insurance occupations (excluding clerical staff )

XIX⫽ professional and technical occupations (excluding clerical staff )

XXIII⫽ clerks, typists, etc.

Source: census for .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008