Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

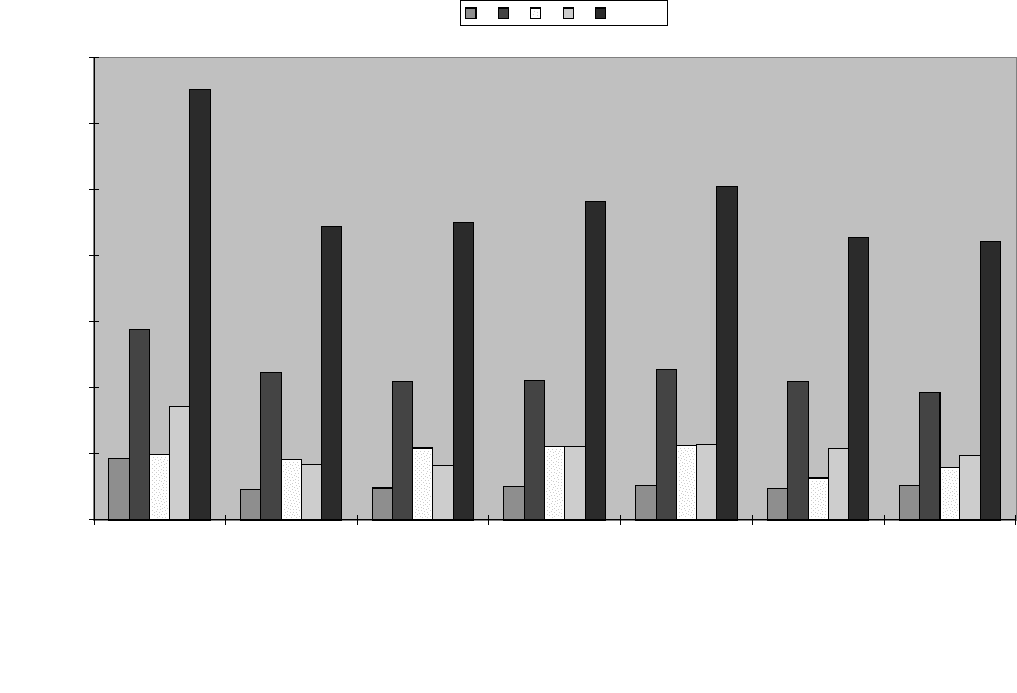

0.00

5.00

10.00

15.00

20.00

25.00

30.00

35.00

3

4

5

6 3 to 6

Greater

London

West

Midlands

West

Yorkshire

South-east

Lancashire

Merseyside Tyneside

Central

Clydeside

Figure . Percentage of private households in selected socio-economic groups, in conurbations,

⫽ higher administrative, professional and managerial (including large employers)

⫽ intermediate administrative, professional and managerial (including teachers and salaried staff)

⫽ shopkeepers and other small employers

⫽ clerical workers

Source: census for .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

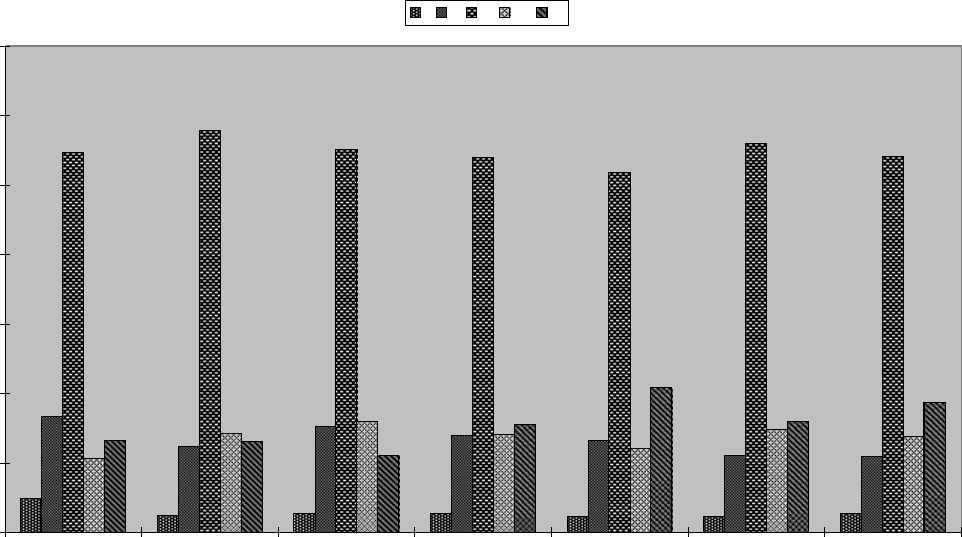

0.00

10.00

20.00

30.00

40.00

50.00

60.00

70.00

Greater

London

West

Midlands

West

Yorkshire

South-east

Lancashire

Merseyside Tyneside

Central

Clydeside

I

II

III

IV

V

Figure . Percentage of males in each Registrar General social class, in conurbations,

Class I⫽ professional and analogous occupations

Class II⫽ intermediate occupations (e.g. many shopkeepers)

Class III⫽ skilled occupations (including foremen and most clerks)

Class IV⫽ partly skilled occupations

Class V⫽ unskilled occupations

Source: census for .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

clerical employment – evident from the late nineteenth century, and accelerat-

ing from the First World War – which (along with a corresponding decline in

the number of employers) was the most striking change in the internal occupa-

tional composition of the middle class. Thus the provincial urban middle class

was numerous and was drawn from a variety of occupations outside as well as

within industry, just as the London (and broader south-eastern) urban middle

class included many members who drew their livings from industry as well as

from commerce and dealing.

This judgement is confirmed by a variety of impressionistic information, for

the twentieth as for the nineteenth century. Thus from the s all provincial

cities – and, by the s, all substantial provincial towns – participated

significantly in middle-class suburbanisation, often initially within city boundar-

ies.

32

Also, while nothing elsewhere could rival Oxford Street’s shops, provincial

cities boasted the substantial department stores which depended to a significant

degree on middle-class customers, especially women.

33

Clearly the proportion of the population which was middle class affected the

social atmosphere of a town or city. Arguably, the social relations of towns with

relatively small middle classes might have been especially stark, featuring a ‘naked

battle between capital and labour, with the proviso that labour often genuinely

deferred to capital’.

34

Yet the existence of a middle class even of per cent of

the population of a later nineteenth-century industrial town could mean a much

more complex pattern of social relations – especially if that middle class included

a series of gradations between the very rich and those not much better-off than

the skilled working class – than in those early industrial localities where large

industrialists faced a large working population with few intermediaries.

35

The internal stratification of the middle class, therefore, shaped the lives of

middle-class urban dwellers and influenced the impact that the middle class had

on Britain’s towns and cities more generally. There were enormous differences

in resources – and in life style (see pp. – below) – between: the upper middle

class of large industrialists and other leading business and professional people; the

middle middle class of middling manufacturers, managers and substantial dealers

and professionals; and the lower middle class of white-collar employees and small

(but employing) retailers and craftsmen. In the Black Country, for example, the

middle class stretched from the Bilston steelmaster Sir Alfred Hickman (who left

£ million at his death in ) through solid professional people like the West

Bromwich surveyor Thomas Rollason (£, in ) to individuals of

modest means such as the Dudley grocer Robert Preece (£, in ).

36

The

Richard Trainor

32

See, for instance, F. M. L. Thompson, ed., The Rise of Suburbia (Leicester, ), ‘Introduction’,

p. .

33

Jackson, Middle Classes, pp. , .

34

Rubinstein, ‘English middle classes in ’, p. .

35

Cf. Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –, –; D. C. Howell and C. Baber, ‘Wales’, in

Thompson, ed., Cambridge Social History, , p. .

36

Somerset House, printed probate calendars.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

urban, like the national, middle class was shaped like a pyramid: the lower

middle class was always by far the most numerous of the three categories; this

predominance probably increased as the numbers of white-collar employees

swelled from faster than numbers declined within the petite bourgeoisie of

small masters and dealers.

37

Yet, even with adverse changes in income tax from

, the upper middle class stayed well off – and numerous in absolute terms

– right down to .

38

Meanwhile, the situation of the lower middle class

remained perilous: even in the interwar years ordinary doctors’ bills threatened

family solvency in the household of the future historian J. F. C. Harrison, for

example.

39

Such vast differences in wealth and income contributed to feelings of super-

iority and resentment among the various strata of the middle class. Hence, for

example, the ‘ratepayers’ movements’ of the early and mid-Victorian years in

which the lower middle class (often in alliance with working-class ratepayers

who, like themselves, bore disproportionate rate burdens) often opposed the

improvements backed by the ‘solid’ middle class, that is its upper and middle

strata.

40

Likewise, even a young man from a comfortable middle-class home, the

future historian Richard Cobb, resented deeply the condescension of his better-

off cousins from Sevenoaks.

41

These contrasts in resources and attitudes among

social strata partly coincided with differences among the major occupational

groups within the urban middle class. Retailers, craftsmen and all but the top

white-collar employees were especially suspect, while there were hints of ten-

sions between industrialists, on the one hand, and professionals and the com-

mercial/financial sector, on the other.

42

Thus, with regard to occupational

groups as well as social strata, the urban middle class would appear, in F. M. L.

Thompson’s words, fragmented into ‘layer upon layer of subclasses, keenly aware

of their subtle grades of distinction’.

43

Yet, other resource-related factors bound together the three major social

strata, and the various occupational groups, of the urban middle class. All but its

lowest fringe had advantages over the majority of the population both in overall

material resources and in terms of mortality and morbidity. The great bulk of

the group also had significant stakes in the middle-class version of ‘respectabil-

ity’ and participated in the middle-class income and property cycles linked to

The middle class

37

For the survival of the latter see G. J. Crossick and H.-G. Haupt, The Petite Bourgeoisie in Europe

– (London, ), pp. , –.

38

Rubinstein, ‘Britain’s elites in the interwar period’, pp. –.

39

J. F. C. Harrison, Scholarship Boy:A Personal History of the Mid-Twentieth Century (London, ),

p. .

40

On these movements see E. P. Hennock, ‘Finance and politics in urban local government in

England, –’, HJ, (), –; Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –.

41

R. Cobb, Still Life: Sketches from a Tunbridge Wells Childhood (London, ), pp. –.

42

Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –; H. J. Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society –

(London, ), ch. .

43

F. M. L. Thompson, The Rise of Respectable Society (London, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

stages of life.

44

In addition, few middle-class people were complacent regarding

these advantages. Rising standards of prestigious consumption strained family

budgets. Also, while economic vulnerability was most typical of the lower middle

class, fear of downward mobility affected most of the group, notably during and

immediately after nineteenth-century slumps and in the s.

45

As working-

class organisations such as trades unions and trades councils began to make a

significant impact on urban as on national life from the late nineteenth century,

resource patterns encouraged greater identification with the broader middle class

even amongst the especially marginal petite bourgeoisie. Likewise, with regard to

occupational distinctions, as the period progressed the more substantial shop-

keepers, craftsmen and white-collar workers increasingly saw themselves, and

were regarded, as members of the ‘solid’ middle class. Thus at the start of the

twentieth century a prosperous Bolton wholesale and retail ironmonger and

general dealer lived near some mill owners and socialised both with doctors and

solicitors.

46

With respect to tensions between industrialists and professionals,

these were not typical of provincial cities and towns such as Leeds, Salford or West

Bromwich, in part because there was no sense of ‘pan-professional identity’, in

part because the working lives of many urban professionals and businessmen were

closely intertwined.

47

With regard to industrialists and the commercial/financial

sector, while in London the externally orientated City elite had limited dealings

with manufacturers, in provincial cities the two sectors were tightly linked. As a

manufacturer from the Chamberlain/Kenrick clan commented, there was no

condescension to manufacturers in Birmingham.

48

Even in London, residence

and social mixing correlated more with social stratum than with occupation.

49

There remains the possibility that the pattern of social stratification within the

Richard Trainor

44

R. J. Morris, ‘The middle class and the property cycle during the Industrial Revolution’, in

T. C. Smout, ed., The Search for Wealth and Stability (London, ), pp. –; Burnett, Housing,

pp. –; V. Berridge, ‘Health and medicine’, in F. M. L. Thompson, ed., The Cambridge Social

History of Britain, –, vol. : Social Agencies and Institutions (Cambridge, ), p. .

45

J. Banks and O. Banks, Prosperity and Parenthood (London, ); Nenadic, ‘Victorian middle

classes’, passim.

46

G. Crossick, ‘Urban society and the petty bourgeoisie in nineteenth-century Britain’, in Fraser

and Sutcliffe, eds., Pursuit, pp. –; Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –; father of Bernard

Thornley, ESRC Qualidata Centre, University of Essex: Family Life and Work Archive,

QD/FLWE/ (hereafter cited as QD etc.).

47

J. Garrard and V. Parrott, ‘Craft, professional and middle-class identity: solicitors and gas engi-

neers, c. –’, in Kidd and Nicholls, eds., Making, pp. –; Morris, Class, Sect and Party,

p. ; Trainor, Black Country Elites, p. . For a partial exception see D. Smith, Conflict and

Compromise (London, ), pp. , . Relations may have become more difficult during the

twentieth century as the relative standing of managers rose (cf. P. Thompson, The Edwardians

(London, ), p. ; H. J. Perkin, The Rise of Professional Society: England since (London,

)).

48

Michael Hope, QD/FLWE/MUC/ C//–; Berghoff, ‘Regional variations’, p. .

49

This is implicit in the analysis of upper-class, upper-middle-class and lower-middle-class districts

of London in H. McLeod, Class and Religion in the Late Victorian City (London, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

middle class differed radically between London and the provinces, making the

two groups almost incomparable, with implications for the ability of the provin-

cial middle class to function not only outside their regions but perhaps inside

them as well. Evidence from the size of fortunes left at death and from income

tax assessments suggests that London enjoyed disproportionate shares of top for-

tunes and incomes.

50

It seems natural that so large and long-established a metrop-

olis, which was also the capital, should contain large numbers – perhaps the

majority – of the most important members of Britain’s professional, commer-

cial and (with the shift to London of company headquarters after the First World

War) even industrial communities.

Yet possible biases in favour of London in probate and income tax material

suggest caution. Also, a study of the wealth left at death by key businessmen

throughout England and Wales suggests that neither London, nor the non-

industrial occupational groups clustered there, were especially likely to generate

wealth.

51

Likewise, analysis of a key taxation return from in terms of

amounts assessed per capita suggests that provincial cities were comparable to

London as a whole (though not to the City in isolation), albeit industrial towns,

like some county towns and ports, lagged well behind both (see Table .).

Moreover, data for the Victorian period on Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester,

the Black Country, Glasgow and other Scottish cities indicate significant

numbers both of large fortunes and of high incomes. The middle classes of these

urban places, therefore, included individuals able to deal on terms of equality

with London’s wealthy elite and with great potential for influence within their

own towns and cities.

52

Differential economic development in favour of the

South-East in the first half of the twentieth century may have increased the

advantages of the metropolis with respect to its absolute number, and propor-

tion, of the upper middle and middle middle classes.

53

But even in the depths of

the Depression of the s J. B. Priestley noted many comfortable homes,

hotels and clubs in the cities and suburbs of the North.

54

Also, the fact that in

The middle class

50

W. D. Rubinstein, ‘British millionaires, –’, Bull. IHR, (), –; Rubinstein,

‘Victorian middle classes’; Rubinstein, ‘Wealth, elites and the class structure’; Rubinstein, Elites

and the Wealthy.

51

T. Nicholas, ‘Wealthmaking in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain; industry v. com-

merce and finance’, Business History, (), –. On sources see, for example, M. Jubb,

‘Income, class and the taxman: a note on the distribution of wealth in nineteenth century Britain’,

HR, (), –; M. S. Moss, ‘William Todd Lithgow: founder of a fortune’, SHR,

(), –; Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –, .

52

Trainor, Black Country Elites, pp. –; Berghoff, ‘Businessmen’.

53

Thus Rubinstein finds (Elites and the Wealthy, pp. –) that, while provincial counties such as

Yorkshire and Lancashire increased their total tax yields in relation to London and the Home

Counties during the mid-nineteenth century, thereafter (until the disappearance, from the inter-

war period, of regionally based tax statistics) the South-East increased its significant residual lead.

Cf. Jackson, Middle Classes, ch. , passim.

54

See, for example, J. B. Priestley, English Journey (London, ), pp. , , , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Richard Trainor

Table . Amounts assessed to income tax, in pounds per head of population, for

selected parliamentary boroughs

City of London . Norwich .

Derby . Leeds .

Westminster . Hull .

London with City . Leicester .

Manchester . Coventry .

Edinburgh . Northampton .

Liverpool . Oxford .

Darlington . Bath .

Glasgow . Sheffield .

Cardiff. Stoke-on-Trent .

Inverness . Ipswich .

London without City . Bedford .

Newcastle-upon-Tyne . Wolverhampton .

Reading . Bolton .

Salisbury . Winchester .

Bristol . Colchester .

Lincoln . Berwick-upon-Tweed .

Wa ke field . Stockport .

Worcester . Preston .

Bradford . Cheltenham .

Nottingham . Dudley .

Birmingham . Plymouth .

Middlesbrough . Oldham .

Halifax . Salford .

Aberdeen . Walsall .

Greenock . Portsmouth .

Brighton . Wednesbury .

Southampton . Blackburn .

Chester . Port Glasgow .

Exeter . Merthyr Tydfil .

Huddersfield . South Shields .

Dundee .

London with city =Chelsea, Finsbury, Greenwich, Hackney, Lambeth, London (City),

Marylebone, Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Westminster.

Population figures are for .

Assessment is for schedule D.

Source: PP ().

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

London’s advantage (see Figure .) in socio-economic group – the

higher administrative, professional and managerial category – was not especially

large in comparison to the provinces suggests that major provincial urban areas

contained many members both of the upper middle class and of the middle

middle class. This impression is further confirmed by returning (in Figure .)

to the five-class data, in which the capital and other parts of the South-east had

only moderate leads in class I. Thus, while outnumbered by their south-eastern

counterparts, the better-off provincial members of the middle class formed a

substantial proportion both of the provincial middle class as a whole and of the

upper ranks of the British middle class more generally.

(iii)

What was the social environment of this socially, occupationally and geograph-

ically diverse urban middle class? During working hours, there were consider-

able differences between the activities of a substantial businessman, a professional

person, a shopkeeper and a white-collar employee. Industrialists and merchants

had considerable autonomy: in the s the father of the Glaswegian J. J. Bell,

for example, worked hard in his city-centre office but on a pattern of his own

choosing before returning to his suburban home for dinner.

55

Professionals

might be more driven by clients but also had significant control over their

working conditions and hours. By contrast, even those retailers and publicans

who employed staff were under pressure to remain at their shops for many of the

long hours during which they opened, especially prior to .

56

White-collar

workers usually had considerably less control than any of these ‘independent’

groups over either the structure or the pace of the working day. Thus the

Glasgow clerk Robert Ferguson, who entered the workforce in a printing firm

just before the First World War, had to heed the office manager, ‘a pretty tough

guy, you had to be on your toes all the time’. Similarly, clerks had to take much

more care of their appearance than did skilled workers who sometimes earned

as much or even more. Ferguson differed from his siblings in manual occupa-

tions because ‘I was very conceited . . . with dress, I had to be. I had to shave

every morning of life, before I went to work.’ He had to give up boxing because

‘If you get marked – it looks terrible the next day.’ Yet Ferguson profited from

other distinctions from manual workers. During fifty-two years of work with

The middle class

55

J. J. Bell, I Remember (Edinburgh, ), pp. –. For a general discussion of hours of work see

H. Cunningham, ‘Leisure and culture’, in F. M. L. Thompson, ed., The Cambridge Social History

of Britain, –, vol. : People and their Environment (Cambridge, ), pp. –.

56

Yet resulting strains on family life might be eased if the employer lived either ‘over the shop’ or

(in small or medium-sized towns) close enough so that, as with Arnold Bennett’s ‘Edwin

Clayhanger’ in the Potteries, it was possible to return home for meals even after a separate resi-

dence had been acquired – Clayhanger (Harmondsworth, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

the same firm, he ‘never started before nine o’clock’ and enjoyed clean working

conditions, security and fringe benefits: ‘I’m the staff you see. And I go about

with my bowler hat on from morning ’til stopping time. My pay was . . . very

regular. Holidays were paid . . . too . . . [for ] staff . . . But [not] the workers.’

57

As white-collar workers began to constitute a larger proportion of the middle

class, Ferguson’s work experience became increasingly typical, as much in its

highly structured, often limited career pattern as in its separation from manual

workers.

58

In terms of housing, as of work, the various strata of the middle class differed

significantly; a highly varied supply of urban dwellings catered to their contrast-

ing demands.

59

In England before the typical lower-middle-class family

lived in a terrace house, while its middle-middle-class counterpart usually had a

‘semi’. Upper-middle-class families favoured detached houses.

60

The latter were

often located in the suburbs which the upper stratum had pioneered, either in

an urban enclave such as Birmingham’s Edgbaston or in a cosy area outside the

city boundary such as Glasgow’s Bearsden. There was a huge contrast between

the modest house of the famous fictional clerk ‘Mr Pooter’ with his single

servant, and the huge, well-staffed piles inhabited by the Chamberlains and

Kenricks.

61

Also, while the distances involved were smaller in provincial cities

than in London, in large towns there was considerable residential segregation

within the middle class by the late nineteenth century. Thus, ‘If London had its

Dulwich, Richmond and Edgware, the same single class exclusiveness was to be

found in Bristol’s Clifton, Cotham and Redland, Nottingham’s Wollaton, West

Richard Trainor

57

QD/FLWE/, pp. , , , –.

58

For the general pattern, which as in Ferguson’s case often persisted well into the post- period,

see D. Lockwood, The Blackcoated Worker (London, ). For the increasing limitations to the

prospects of urban clerks, see G. L. Anderson, Victorian Clerks (Manchester, ); and G. L.

Anderson, ‘The social economy of late Victorian clerks’, in G. Crossick, ed., The Lower Middle

Class in Britain, – (London, ), pp. –. On career patterns, see K. Stovel, M.

Savage and P. Bearman, ‘Ascription into achievement: models of career systems at Lloyds Bank,

–’, American Journal of Sociology, (), –; M. Savage, ‘Discipline, surveillance

and the “career”: employment on the Great Western Railway, –’, in A. McKinlay and

K. Starkey, eds., Foucault, Management and Organization Theory (London, ), pp. –. For the

complex way in which social mobility affected the urban middle class see A. Miles, Social Mobility

in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century England (Basingstoke, ).

59

M. A. Simpson and T. H. Lloyd, eds., Middle Class Housing in Britain (Newton Abbot, ),

‘Introduction’, p. .

60

Thompson, Rise of Respectable Society, p. . There were, of course, significant regional varia-

tions (M. J. Daunton, ‘Housing’, in Thompson, ed., Cambridge Social History, , p. ), not least

with regard to Scotland, where many middle-class families lived in tenement flats, some of which

were large and opulent.

61

G. Grossmith and W. Grossmith, Diary of a Nobody (Bristol, ); Cannadine, Lords and Landlords.

For the early process of suburbanisation see Thompson, Rise of Suburbia, p. ; for the significance

of servant-keeping to the nineteenth-century middle class, see L. Davidoff, ‘The family in

Britain’, in Thompson, ed., Cambridge Social History, , p. ; and Thompson, Rise of Respectable

Society, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Bridgeford [sic] and Mapperley Park, or Manchester’s Alderley Edge and

Wilmslow.’

62

Variations in housing, then, not only ‘mirrored’ social distinctions

within the middle class but also ‘helped to define and reinforce them’.

63

None the less, aspects of urban middle-class housing also drew the strata

together, albeit in ways which differed from region to region. Throughout the

middle class, by the beginning of our period, there was a strong desire for domes-

ticity, comfort and privacy. Within the home this meant – allowing for huge

contrasts in scale and quality – elaborate decoration and furnishings. As the

American visitor Ralph Waldo Emerson noticed, ‘If [an Englishman] . . . is in

[the] middle condition, he spares no expense on his house . . . it is wainscoted,

carved, curtained, hung with pictures and filled with good furniture.’

64

Middle-

class homes also emphasised clear categorisation of rooms, isolating families from

their servants.

65

In terms of location, the middle class favoured distinct separa-

tion from working-class houses, significant distancing from their own place of

work and (money permitting) a low-density neighbourhood. Thus, aided by

transport innovations, even the lower middle class increasingly suburbanised,

especially from the s.

66

In terms of location, if not scale, of housing they

then resembled the vast majority of their middle-class betters: even in

Lancashire, Yorkshire and the Home Counties only a small minority of the

upper middle class ventured farther into the countryside than the urban fringe.

67

The residential changes which affected the urban middle class during the

period – – increased ownership, the diffusion of the ‘semi’ and acceler-

ated suburbanisation – reinforced these common features. In contrast to the

pre- tradition of middle-class renting, between the world wars ‘owner-

occupation developed as the typical middle-class tenure’, covering just over half

the group by . The proportion was especially high in those towns, largely

found in the South-East, with especially large middle-class populations.

68

As a

result, ‘much of the middle middle and some of the lower middle class’ could

become property owners.

69

Builders catered for this swollen demand particularly

through ‘semis’. Well-adapted to the modest means of the new owners, these

houses represented a ‘change of both lifestyle and status’ for families like the

The middle class

62

Burnett, Housing, p. , pp. – (quote); Thompson, Rise of Suburbia, p. . Cf. R. Dennis,

English Industrial Cities of the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, ), chs. , and ; C. Pooley,

‘Residential differentiation in Victorian cities: a reassessment’, Transactions of the Institute of British

Geographers, new series, (), –.

63

Thompson, Rise of Respectable Society, p. .

64

R. W. Emerson, English Traits (London, ), p. , quoted by Burnett, Housing, p. .

65

Daunton, ‘Housing’, p. ; Burnett, Housing, p. ; R. G. Rodger, Housing in Urban Britain

– (Cambridge, ), p. .

66

Thompson, Rise of Suburbia, pp. , .

67

R. H. Trainor, ‘The gentrification of Victorian and Edwardian industrialists’, in A. L. Beier, D.

Cannadine and J. M. Rosenheim, eds., The First Modern Society (Cambridge, ), pp. –.

68

Daunton, ‘Housing’, p. ; M. Swenarton and S. Taylor, ‘The scale and nature of the growth of

owner-occupation in Britain between the wars’, Ec.HR, nd series, (), –; Burnett,

Housing, p. .

69

R. McKibbin, Classes and Cultures (Oxford, ), p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008