Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

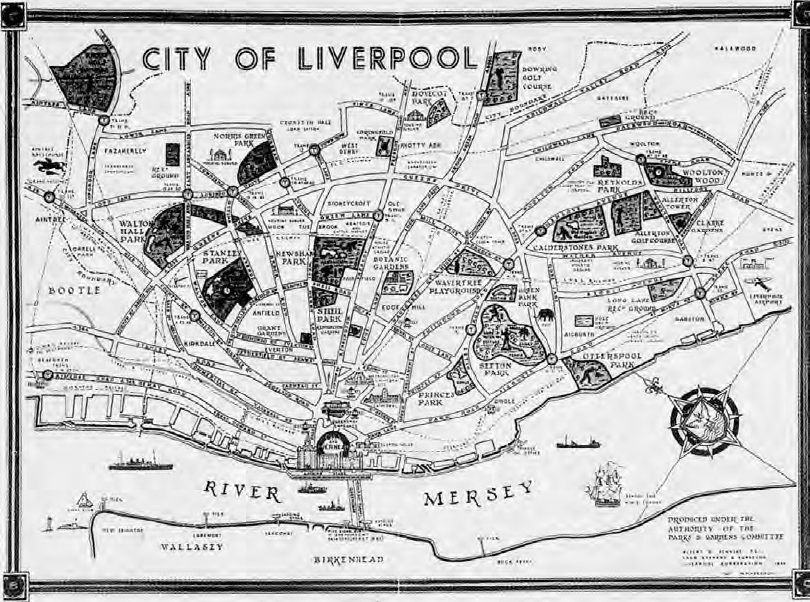

Map . Liverpool parks . The inner ring was formed –, the outer parks were added

later.

Source: Hazel Conway, People’s Parks:The Design and Development of Victorian Parks in Britain

(Cambridge, ).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

numerous strictly enforced rules, drawing a careful distinction between public

parks and unregulated commons ( just as public libraries distinguished between

the uncontrolled effusions of the market place in print and weightier tomes).

This contrast was emphasised in the case of Kennington Common (enclosed and

emparked in , four years after it hosted the last great Chartist demonstra-

tion) and Mousehold Heath in Norwich (regulated in ). Nevertheless, com-

mercial pleasure gardens also found it necessary to deploy policemen to ‘ensure

respectability and preserve order’: an uncivil minority needed restraint to max-

imise the majority’s enjoyment. And there is no doubt that parks were very

popular, partly because of the free entertainment provided from their band-

stands: one August Sunday in there were , visitors to Greenwich Park,

, to Regent’s Park and , to Victoria Park (while , visited

Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea, and , excursionists left London stations).

25

Cremorne was one of a number of competitors with Vauxhall Gardens for

which nineteenth-century urbanisation created new demand. Admittedly,

London’s Vauxhall closed in , but though less popular than the free public

parks most of the pleasure gardens attracted sufficient custom until the s and

s, by which time ground landlords were able to see more profit through

their redevelopment. As with fairs, however, the demise of central gardens pro-

moted the careers of some further out – like Riverside Gardens, North

Woolwich. Those which survived past - had diversified into sporting

facilities, and served regional and national rather than simply local publics –

principally the Crystal Palace’s Sydenham Gardens (), and Belle Vue

(founded in to compete with Manchester’s Vauxhall).

26

In big cities the distribution of public parks was usually skewed away from the

Playing and praying

25

Thomas Kelly, A History of Public Libraries in Great Britain, – (London, );

Cunningham, Leisure in the Industrial Revolution, pp. –, –; Neil McMaster, ‘The battle

for Mousehold Heath’, P&P, (), , –; Russell, ‘The pursuit of leisure’, p. ;

Reid, ‘Labour, leisure and politics’, p. ; ‘The London Sunday’, quoted from The Star in

Birmingham Daily Press, Aug. , cf. Hewitt, The Emergence of Stability in the Industrial City,

pp. –; Winter, London’s Teeming Streets, pp. –, –; Nan H. Dreher, ‘The virtuous and

the verminous: turn-of-the-century moral panics in London’s public parks’, Albion, (),

–. For discussion of non-bourgeois ‘rational recreation’ see Faucher, Manchester in ,

p. n. , Reid, ‘Labour, leisure and politics’, ch. ; and Martha Vicinus, The Industrial Muse

(London, ), pp. –, n. . A technologically sophisticated age should not underesti-

mate the impact of the penny reading, the diorama and the magic lantern.

26

J. Ewing Ritchie, The Night Side of London, nd edn, revised (London, ), pp. –, ,

–; A Guide to Belle Vue Gardens (Manchester, ); Kidd, Manchester, pp. –, –, ;

Taine, Notes on England, pp. –; R. D. Altick, The Shows of London (London, ), pp. –,

–, ; Reid, ‘Labour, leisure and politics’, pp. ‒, –; Warwick Wroth, The London

Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century (London, ; reprint), pp. –; Warwick

Wroth, Cremorne and the Later London Gardens (London, ); Mark Girouard, Victorian Pubs

(London, ), p. ; VCH, Hull, , p. ; Gregory Anderson and Barbara Ferguson, ‘James

Reilly. An artisan manufacturer in Victorian Manchester’, Manchester Region History Review,

(), ‒.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

most densely populous areas and towards the outskirts, where large blocks of land

remained. Admission figures to such parks in Birmingham in the s suggest

an annual average of ten visits per capita, which has been seen as low (yet this was

relatively early, and thirty-four visits per capita made to Birmingham’s many

cinemas in provide a different perspective). In the s realisation of the

problem of location led larger cities to provide local playgrounds for the areas of

densest population, though in London’s ‘central and most congested districts’ in

the s the street remained the popular and ‘often the only playground’ for the

younger children. Nevertheless, on Bank Holidays Londoners found compen-

sation on trips to Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest and other commons pre-

served after lengthy struggles.

27

There were other means of escape from the towns. For men an important way

was to join the Volunteer Force (a ‘dominantly urban’ movement), for their

annual camps offered subsidised fellowship and fresh air. Freer spirits went ram-

bling: Glasgow’s Saturday-afternooners in , Manchester’s YMCA and

Sheffield’s socialists, in later decades. Cycling was enormously popular in the

s, with clubs in London, perhaps mainly lower middle class. More time

and higher living standards in the interwar period increased involvement, and in

the s old ‘rambling’ became new youthful ‘hiking’ – fashionable along with

cycling, camping and other manifestations of ‘outdoor’ feeling: Hull had

- cycling club members in .

28

However, the unsung (largely male) working-class pastime of coarse fishing

facilitated the movement of far larger numbers from cities to rural settings under

the aegis of pub-based angling clubs. There were in London by , and

– more impressive in per capita terms – in Norwich in ; Sheffield’s had an

extraordinary , members by . In the interwar years the motor chara-

banc and motor bike and a new trend towards employer sponsorship allowed

Douglas A. Reid

27

Reid, ‘Labour, leisure and politics’, pp. –; Bramwell, ‘Public space’, pp. –; Browning

and Sorrell, ‘Cinemas and cinema-going’, ; Trainor, Black Country Elites,p.; Maver,

‘Glasgow’s public parks’, ; New Survey of London Life and Labour, , p. ; Conway, People’s

Parks, pp. –, ; Robert Hunter, ‘The movements for the inclosure and preservation of

open lands’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, (), –, ; Jones, Workers at Play,

pp. , ; Thompson, Hampstead, chs. –; D. Owen, The Government of Victorian London,

– (Cambridge, Mass., and London, ), pp. –, –, , ; Anthony Taylor,

‘“Commons-stealers”, “land-grabbers” and “jerry-builders”: space, popular radicalism and the

politics of public access in London, –’, International Review of Social History, (),

–.

28

Cunningham, The Volunteer Force, pp. , –; King, ‘Popular culture in Glasgow’, p. ;

Fraser, ‘Developments in leisure’, pp. –; David Prynn, ‘The Clarion Clubs, rambling and the

holiday associations in Britain since the s’, Journal of Contemporary History, (), –;

Ann Holt, ‘Hikers and ramblers: surviving a thirties’ fashion’, International Journal of the History of

Sport, (), –; David Rubinstein, ‘Cycling in the s’, Victorian Studies, (),

–, cf. –, , –; R. Holt, Sport and the British (Oxford, ), pp. –; Richard

Evans and Alison Boyd, The Use of Leisure in Hull (Hull, ), p. ; Jennings and Gill, Broadcasting

in Everyday Life,pp.‒, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

angling to maintain its position as one of the chief outdoor activities. The motor

charabanc also facilitated excursions to previously untouched beauty spots by a

rapidly notorious (because noisy and well-victualled) phenomenon – the

‘tripper’. Equally, the massed-ranked chalets of the new holiday camps were

rather reminiscent of cities by the sea.

29

(iii)

Drink, however, was ‘the shortest cut out of Manchester’, or ‘out of

Whitechapel’, or any city. Yet public houses constituted the chief nineteenth-

century leisure venue for many other reasons than seeking solace for a desperate

or humdrum existence. Alcohol performed numerous functions – commercial,

cultural, nutritional and recreational, as well as medical and psychological – and

because of this – and because they were free, warm, light and offered company

(predominantly but not wholly male before ) as well as invigoration and

refreshment – public houses were ubiquitous in towns, and their contribution to

popular leisure immense. They were centres of sport, news, games, entertain-

ment, debate and culture, for urban landlords were leisure entrepreneurs, as that

notable offshoot and ultimate competitor, the music hall, illustrates. Pubs –

selling beer and spirits – clustered particularly on transport routes, and on main

streets, whereas the , beerhouses created following the Beer Act were

concentrated in working-class suburbs. By the s in big cities, and even

smaller towns like Bolton, many pubs shouted their presence by plate-glass

windows, ‘flaring gas lights in frosted globes and brightly gilded spirit casks’.

Following a frenzy of competition among big brewers in the s and s

they reached a lavish climax of engraved glass, mahogany and mosaic as verita-

ble ‘palaces’ for drinking – feeding on the continuous flow of custom in the big

towns, and the free-spending population of the larger ports and resorts.

30

The architectural flashiness of the city-centre drinking palaces should not

blind us to the much more basic beerhouses and pubs – key centres of social life

Playing and praying

29

Lowerson, ‘Brothers of the angle’, p. ; Lowerson, ‘Angling’, pp. ‒; Hawkins, Norwich, p.

; C. E. M. Joad, ‘The people’s claim’, in Clough Williams-Ellis, Britain and the Beast (London,

), pp. –; Colin Ward and Dennis Hardy, Goodnight Campers: The History of the British

Holiday Camp (London, ).

30

Joad, ‘The people’s claim’, p. ; Durant, The Problem of Leisure, p. ; Harrison, Drink and the

Victorians, pp. –; B. Harrison, ‘Pubs’, in Dyos and Wolff, eds., The Victor ian City, , pp. –;

Rudolph Kenna and Anthony Mooney, People’s Palaces:Victorian and Edwardian Pubs of Scotland

(Edinburgh, ), pp. , ; Rowntree, Poverty, p. ; G. B. Wilson, Alcohol and the Nation

(London, ), pp. –; Poole, Popular Leisure and the Music Hall, p. ; ‘Shadow’ (Brown),

Midnight Scenes, pp. –; Girouard, Victorian Pubs, pp. , –, –, –, , , –,

–; Joseph Rowntree and Arthur Sherwell, Temperance Problem and Social Reform, th edn

(London, ), pp. –; Alan Crawford and Robert Thorne, Birmingham Pubs –

(Birmingham, ), [pp. –]; T. R. Gourvish and R. G. Wilson, The British Brewing Industry

– (Cambridge, ), pp. , –, –, –, –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

in working-class neighbourhoods and smaller towns. Charles Booth drew atten-

tion to ‘hundreds of respectable public-houses’ in London’s East End, where,

beneath the eye of ‘a decent middle-aged woman . . . the whole scene [was]

comfortable, quiet, and orderly’. In Edwardian Norwich the public house

remained the working man’s ‘centre of social intercourse’, particularly because

‘compared with larger cities the Norwich public-house . . . [was] smaller and

more home-like’. And in Middlesbrough, the ‘ever-present, ever-accessible

public-house’ was a place of ‘society, conviviality, amusement’. Booth believed

that pubs played ‘a larger part in the lives of the people than clubs or friendly

societies, churches or missions, or perhaps than all put together’, although after

the price rises and shortened hours imposed during – the working men’s

clubs became very much more important. Moreover, on the new interwar estates

few pubs were built; brewers offered massive ‘Olde English’ roadhouses instead.

31

To the migrant young, however, it was precisely the brilliant lights, the ‘buzz’

of large town life, which constituted one of its attractions (as well as shorter

working hours). In Llewellyn Smith’s formulation, London enticed its immi-

grants through ‘the contagion of numbers, the sense of something going on, the

theatres and music halls, the brightly-lighted streets and busy crowds – all, in

short, that makes the difference between the Mile End fair on a Saturday night,

and a dark and muddy country lane, with no glimmer of gas and with nothing

to do’. Leisure entrepreneurs knew the value of glitz. Pleasure gardens were

famous for their illuminated lanterns and brilliant pyrotechnics; pubs provided

dazzling spectacles from the s, as did handsomely appointed music halls from

the s; the Savoy Theatre became the first public building in the world lit by

electricity in ; Italian Renaissance and Baroque style-books were pillaged

to create opulent, exotic variety palaces in the decades before . London was

the ‘Great City of the Midnight Sun / Whose day begins when day is done’.

Even in Edwardian Middlesbrough pubs in ill-lit side streets threw out a vividly

welcoming ‘blaze of light’.

32

Douglas A. Reid

31

Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London, First Series: Poverty, , pp. –; Hawkins, Norwich,

p. ; [Florence] Bell, At the Works (London, ), p. ; Bill Bramwell, Pubs and Localised

Communities in Mid-Victorian Birmingham (Dept of Geography and Earth Science, Queen Mary

College, University of London, Occasional Paper no. , ); John Taylor, From Self-Help to

Glamour: The Workingman’s Club, – (Oxford, ); Phyllis Willmott, Growing up in a

London Village (London,), pp. –; Laurence Marlow, ‘A menace to sobriety? The drink

question and the working man’s club, c. –’, in Voss and Holthoon, eds., Working Class

and Popular Culture, pp. –; Terence Young, Becontree and Dagenham: A Report Made for the

Pilgrim Trust (London, ), pp. , , , , –, , ; Mass-Observation, The Pub and

the People, ; Crawford and Thorne, Birmingham Pubs, pp. [–] and plates and .

32

Llewellyn Smith cited in J. A. Banks, ‘The contagion of numbers’, in Dyos and Wolff, eds., The

Victorian City, , pp. ff; M. Loane, From Their Point of View (London, ), ch. (‘Why the

poor prefer town life’), specifically pp. , ; cf. Standish Meacham, A Life Apart: The English

Working Class – (London, ), pp. –; Bell, At the Works, pp. , ; Souvenir:

Empire Theatre, Birmingham, , p. ; John Earl, ‘Building the halls’, in P. Bailey, ed., Music Hall

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

As well as migrants the enticements of cities drew in thousands of visitors and

tourists. In the s Manchester Whit week closed with ‘gaping Saturday’ as so

many people travelled in from the neighbourhood and ‘urged by intense curi-

osity, insisted on seeing everything in the shop windows and visiting the

Exchange and College’. This pattern was repeated in other provincial cities, as

railway excursions, and regular services, conveyed people to exhibitions, fairs,

museums, music halls, shops, sporting fixtures and theatres. It is significant that

music halls emerged more or less contemporaneously in both London and major

provincial towns, for their growth was a function of the concentrated market for

entertainment presented by all major towns and of the intense competition

between beerhouses and other licensed houses following the Beer Act. The

prototype halls were the Grecian Saloon at the Eagle Tavern on London’s City

Road, and the Star Concert Room at Bolton’s Millstone Inn; by the s there

were ‘announcements of “Free and Easy”, and “Free Concert” . . . in every

direction’. Significantly, the chain of ‘Empire Palaces’ that dominated the indus-

try by was built by H. E. Moss of Greenock, Richard Thornton of South

Shields and Oswald Stoll of Liverpool.

33

Nevertheless, London, with a population of nearly million in and over

million by , undoubtedly took the palm for the concentration and variety

of its cultural and entertainment attractions – from the Abbey to the Zoo. Its

capacity to draw national audiences via the railway system was demonstrated in

at the Great Exhibition, when as many as a sixth of its million visitors trav-

elled from afar by rail. The Crystal Palace was important in both the metropoli-

tan and the national history of leisure. With its music, ornamental gardens and

firework displays it helped to erode the place of Vauxhall, and its numerous con-

tests, festivals and shows drew brass bandsmen, cage-bird fanciers, Co-operators,

football fans, Friendly Society members, Handel-lovers, jazz bandsmen,

Playing and praying

(Milton Keynes, ), pp. –; Roger Dixon and Stefan Muthesius, Victorian Architecture, nd

edn (London, ), pp. –; Victor Glasstone, Victorian and Edwardian Theatres (London, ),

pp. –, –, –; Charles D. Stuart and A. J. Park, The Variety Stage (London, ), pp.

–; Gavin Weightman, Bright Lights,Big City (London, ), pp. –; Audrey Field, Picture

Palace: A Social History of the Cinema (London, ), pp. , ; ‘Great City’, cited in Donald

Read, England –:The Age of Urban Democracy (London, ), p. .

33

Manchester Guardian, May , cited in Kenneth Allan, ‘The recreations and amusements of

the industrial working class in the second quarter of the nineteenth century with special refer-

ence to Lancashire’ (MA thesis, University of Manchester, ), p. ; Wilson, Alcohol and the

Nation, p. . Unlike circuses, theatrical booths or fairground rides, music halls were not regu-

larly translated to rural locations: Clive Barker, ‘The Chartists, theatre reform and research’,

Theatre Quarterly, (), –; Murfin, Lake Counties, pp. –; Stuart and Park, The Variety

Stage, pp. ‒; Girouard, Victorian Pubs, pp. –; Poole, Popular Leisure and the Music Hall,pp.

–, n. ; Birmingham Journal, Apr. ; Kathleen Barker, ‘The performing arts in

Newcastle upon Tyne’, in Walton and Walvin, eds., Leisure in Britain, p. ; Dagmar Kift, The

Victorian Music Hall (Cambridge, ), pp. –; Russell, ‘The pursuit of leisure’, pp. ‒;

G. J. Mellor, The Northern Music Hall (Newcastle, ), pp. –; Andrew Crowhurst, ‘Oswald

Stoll: a music hall pioneer’, Theatre Notebook, (), –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Salvationists, Sunday School pupils, Temperance workers, and others, right

through until the conflagration of devoured Paxton’s iron and glass master-

piece – although by this time some of its other functions had been usurped by

Olympia (), Earl’s Court () and Wembley ().

34

Tourists and provincial excursionists had also boosted theatre audiences in

, though few ventured east to the thriving theatres in Hoxton and

Shoreditch, which catered for local workers at one sitting, and later for return-

ing city clerks. Here, and in lesser popular theatres and ‘penny gaffs’ catering for

even the poorest, migrants and settlers found warmth, sociability, entertainment

and excitement. As in other cities they cheered Shakespearean ghosts and battles

and melodrama – including Boucicault’s much-adapted Poor of Paris, London,

Birmingham etc. However, population movements and the development of music

hall and cinema meant that East End theatre was a shadow of its former self by

. By contrast, suburban train services in the s and s and the cutting

of Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road in the s stimulated the

‘West End’, hosting the genial satires of Gilbert and Sullivan and a new drawing-

room drama for the train-borne middle classes. The West End boom resumed

after producing ninety theatres (Manchester had nine, Birmingham,

Glasgow and Liverpool six each, and Edinburgh, Leeds, Sheffield, Belfast,

Newcastle and Cardiff three apiece).

35

However, the glamorous ‘super-cinemas’of the s ossified theatrical devel-

opment. Moving pictures had first been seen in music halls (and fairs) in .

The cuckoo did not immediately take over the nest, but by - London had

ninety-four purpose-built cinemas, and altogether. Many were rudimentary

‘blood tubs’, a few were ‘picture palaces’ on Oxford Street catering for the ‘car-

riage trade’. Cinema received enormous impetus during – and by

Douglas A. Reid

34

Altick, The Shows of London, pp. , , , –, ; Simmons, Victorian Railway, p. ; K.

Baedeker, London and its Environs (London, ), pp. ‒; Chadwick, The Victorian Church, ,

pp. –; Michael Musgrave, The Musical Life of the Crystal Palace (Cambridge, ), pp. –,

–, ‒, –, –; Lawrence Magnanie, ‘An event in the culture of co-operation:

national co-operative festivals at Crystal Palace’, in S. Yeo, New Views of Co-operation (London,

), pp. –; Jones, Workers at Play,p.; New Survey of London Life and Labour, , pp. ,

–.

35

Clive Barker, ‘The audiences of the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton’, Theatre Quarterly, , no.

(), ‒; Jim Davis, ‘The East End’, in M. R. Booth and J. H. Kaplan, eds., The Edwardian

Theatre: Essays on Performance and the Stage (Cambridge, ), pp. –; F. Sheppard, London

(Oxford, ), p. ; New Survey of London Life and Labour, , pp. –; Michael R. Booth,

English Melodrama (London, ); D. A. Reid, ‘Popular theatre in Victorian Birmingham’, in

David Bradby, Louis James and Bernard Sharratt, eds., Performance and Politics in Popular Drama

(Cambridge, ), pp. –; Jeremy Crump, ‘The popular audience for Shakespeare in nine-

teenth century Leicester’, in Richard Foulkes, ed., Shakespeare and the Victorian Stage (Cambridge,

), pp. ‒; John Springhall, ‘Leisure and Victorian youth: the penny theatre in London

–’, in J. S. Hurt, ed., Childhood, Youth and Education in the Late Nineteenth Century

(Leicester, ); Allardyce Nicoll, English Drama – (Cambridge, ), pp. , ; A. A.

Jackson, The Middle Classes, – (Nairn, ), pp. –, –, –, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

outnumbered theatre and music hall seats in London by two to one. Continuous

strip neon lighting introduced in the s also contributed to the capital’s

attractions: to contemporaries it imparted a carnival-like air to Piccadilly.

Though blacked out in the war, by the later s London had resumed its mag-

netic role.

36

(iv)

Commercial entertainment exemplifies the point that all towns are markets,

centres of competition. However, they are also social arenas in which individu-

als and communities develop their sense of identity. How far was urban identity

affected by the development of leisure in nineteenth- and twentieth-century

towns and cities?

Take the music halls, whose repertoire consisted of singing, instrumental

music, comic patter, clowns, acrobats and dancing, evolving from earlier fare

available in streets (especially ballads), bohemian singing saloons, pleasure

gardens, circuses and theatres. By the s the first London ‘stars’ emerged in

the shape of the lion comiques like George Leybourne – whose regular provincial

tours helped to nationalise taste – with his evocation of the insouciant London

toff, ‘Champagne Charlie’, on ‘a spree’. The success of ‘swell songs’ can be seen

as an indication of how even the limited leisure time available to young urban

lower-class men could be used to construct a liberating alter ego – a fantasy

achieved through the surrogate means of wearing a tawdry version of the toff’s

garb, smoking cheap cigars and empathising with his music hall representation.

In fact the ‘counterfeit swell’ was a recognisable urban type even before the

s, as is indicated by a ballad anatomy of the crowds at Birmingham’s Vauxhall

on Sunday evenings, when entry was free to circumvent the law: they included

‘half of the Brummagem people’, including soldiers, ‘factory lasses’, ‘young

widows’, ‘old bachelors’, courting couples and old marrieds, ‘trades and

mechanics’, ‘snobs [cobblers] and tailors’, ‘naughty boys . . . strutting about . . .

smoking cigars’, and ‘young swells in Paletots white’, ‘reeling along / Singing

“I’m a gent”, or some such song’. Leisure was liberating – as a writer in the

Dublin University Magazine recognised in : ‘From being machines, fit only

for machine work, or inert quiescence, the masses . . . [were] given the liberty

of being men, gentlemen indeed’ by their leisure time: experiencing that

‘coveted attribute of gentility’ – ‘the power of being “at large”’. Leisure implied

freedom from the restrictions of work (and social obligations), freedom to

Playing and praying

36

Robert Graves and Alan Hodge, The Long Week-end: A Social History of Great Britain, –

(London, ), pp. –, ; J. Richards, The Age of the Dream Palace (London, ), pp.

–; Weightman, Bright Lights, Big City, pp. –; Rowson, ‘A statistical survey of the cinema

industry’, ; Seebohm Rowntree and G. R. Lavers, English Life and Leisure (London, ),

p. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

dispose of time at will and freedom to role play an alternative existence.

Furthermore, male impersonators Nellie Power and Vesta Tilley created ‘female

swells’, partly mocking, partly testifying to the popularity of the male type and

partly suggesting possibilities of female freedom. There was much more to the

music hall than swell songs, but this stream of urban popular culture enabled

the youthful component of the audience the pleasurable fantasy of escaping from

the confines of their everyday existence, of being men and women ‘of the

world’, even in unglamorous Carlisle.

37

By contrast, the group of talented comic performers from poor backgrounds

who emerged in the s – Marie Lloyd, Gus Elen, Dan Leno and others – can

be interpreted as representing social realism regarding the everyday realities of

the hard life lived in London’s East End – running the gamut from beer to wed-

dings, constituting a Cockney ‘culture of consolation’. However this is not

necessarily incompatible with the ‘swell’ hypothesis, provided that music hall

audiences are not perceived as monolithic. It is often assumed (invalidly, as we

have seen), that music hall was essentially a London creation, but adopting G.

Stedman Jones’ view that the truest representatives of East End culture were Dan

Leno and Charlie Chaplin, ‘little men, perpetually “put upon” . . . products of

city life’, whose fate depends on luck rather than their own efforts, there seems

no reason why such figures should not resonate equally in Liverpool or Glasgow.

Similarly, when Gus Elen sang with wry ironic realism that ‘You could see to

’Ackney Marshes / If it wasn’t for the ’ouses in between’ he gave expression to

a sense of the boundaries imposed by bricks and mortar which would be appre-

ciated in the inner districts of Hull or Manchester. On the other hand, towns

and cities inspired loyalty as well as a desire to escape. ‘I belong to Glasgae, dear

old Glasgae town’, sang Will Fyffe (in the s), and ‘on Saturday night Glasgae

belongs to me!’. At one level this was merely a comic comment on the numer-

ous Glaswegians who drank too much, but, at another, its chorus gave expres-

sion to a basic affection for the city which represented the framework for people’s

lives.

38

However, local sentiment regarding cities, and parts of cities, was more

Douglas A. Reid

37

P. Bailey, ‘Champagne Charlie: performance and ideology in the music hall swell song’, in

J. S. Bratton, ed., Music Hall (Milton Keynes, ), pp. – ( for Dublin quotation); see also

Jane Traies, ‘Jones and the working girl: class marginality in music-hall song, –’, in ibid.;

Morning Chronicle (London), Mar. , for Vauxhall; Peter Davison, Songs of the British Music

Hall (New York, ), pp. –; Martha Vicinus, The Industrial Muse (London, ), pp.

–; Russell, Popular Music in England, pp. –, ; J. R. Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight

(London and Chicago, ), pp. –; Kift, The Victorian Music Hall,pp.– esp. –;

Murfin, Lake Counties, p. .

38

G. Stedman Jones, ‘Working-class culture and working-class politics in London, –: notes

on the remaking of a working class’, Soc. Hist., (), –; Russell, Popular Music in England,

pp. –, ; Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight, pp. –; Davison, Songs,pp.–;

MacInnes, Sweet Saturday Night, pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

frequently given expression in the context of competitive sport, and especially

football (with its rugby variant particularly popular in certain localities, princi-

pally due to accidents of provenance rather than to any supposed link between

brawn and rugby in heavy-industrial areas). The emergence of mass spectator

sports on a national scale was one of the outstanding features of the period since

: they were relatively disciplined, time-limited and professionalised phe-

nomena, well suited to the new, ordered, time-constrained, competitive urban

environment (variously contrasting with ‘folk-football’, animal-baiting and

cricket, with their rural associations and origins).

39

A ‘football fever’ swept over Midland and northern towns in the s.

Despite the earlier suppression of set-piece street matches, football was like a

subterranean stream, reappearing whenever the crust of repression was weak-

ened – at Owenite galas in the s, on works’ trips and in the new parks in

the s. In the s and s, however, spontaneous popular enthusiasm was

channelled into the new codified games which emerged from the public schools:

spreading in the North – in Harrow’s ‘kicking’ version – from Sheffield FC and

industrial Turton, near Bolton; and – in Rugby’s ‘handling’ version – from

Manchester, Bradford and Leeds. Historians have asserted the missionary zeal of

amateur sportsmen to provide the working classes with disciplined, athletic,

‘rational recreation’ and much has been made of the church affiliations of many

clubs. However, hard evidence of footballing parsons is scarce (and even more

so of footballing ministers) – though there were certainly cricketing clerics, ‘fair

play’ and obedience to the umpire being considered analogous to Christian

ethics and social order. It seems therefore that many church football teams simply

represented Bible class and Sunday School friendships developed in sporting

directions, some as winter counterparts of cricket teams. Equally the smaller

number of work-based football clubs were more often employee rather than

employer sponsored. The majority of clubs actually took their provenance from

places: public houses, public parks, streets and neighbourhoods – such as

Blackburn’s Gibraltar Street Rovers, or ‘Ardwick’ and ‘Newton Heath’ (later

Manchester City and United). This suggests that though football is often con-

sidered a ‘mass leisure’ pursuit much of it reflected existing localised patterns of

urban sociability. Even in when professional clubs attracted nearly a

million spectators weekly, another , clubs involved half a million amateur

players.

40

Playing and praying

39

David Russell, ‘“Sporadic and curious”: the emergence of rugby and soccer zones in Yorkshire

and Lancashire, c. –’, International Journal of the History of Sport, (), esp. –.

40

H. F. Abell, ‘The football fever’, Macmillan’s Magazine, (), –; Reid, ‘Labour, leisure

and politics’, pp. , , –; Percy M. Young, A History of British Football (London, ),

pp. , –, –; Mason, Association Football, pp. –, –; Gareth Williams, ‘Rugby

Union’, in Mason, ed., Sport in Britain, pp. –; Russell, ‘“Sporadic and curious”’, esp.

–; Robert W. Lewis, ‘The genesis of professional football: Bolton-Blackburn-Darwen, the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008