Daunton M. The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3: 1840-1950

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

sociable entertaining pastime’ after the First World War, with over , amateur

groups in Britain by the s (by no means all middle class). However, the most

distinctive innovations in middle-class leisure were sporting, especially tennis and

golf. Before the s cricket was the most sophisticated suburban sport, pro-

viding young commercial and professional men with pleasant summer exercise,

and, by association, affirming gentlemanly aspirations. There was little for

women but croquet until young suburbans took up the newly invented lawn

tennis in the s. It spread rapidly through the medium of the club: one was

founded in the very first year of Bedford Park garden suburb, Ealing, in ,

and Nottingham’s exclusive Park estate had virtually no social facilities but tennis

courts. Badminton and table tennis also became popular, but lawn tennis took

the palm, with affiliated clubs multiplying tenfold by . Tennis appealed to

the energetic young; their marriage-broking, status-conscious mothers valued

tennis pavilion teas and dances. Golf had some democratic credentials when

played on Scottish seaside links, but in club form was a very different phenom-

enon. Male suburbanites took to the game with alacrity – seeking moderate

exercise (especially in middle age) in an associational form which protected or

enhanced social status. Thus Glasgow had twenty private golf courses for busi-

ness types by , compared with two public courses. In England, there were

, courses by , some of them in small country towns and seaside resorts.

Stanmore, Middlesex, was typical of the suburban type in requiring two propos-

ers for new members, granting ‘Ladies’ and some ‘artisans’ inferior status, and

excluding Jews. In industrial towns like Blackburn, with no extensive middle-

class suburbs, the golf club (), served the whole town, kept exclusive by a

limit of seventy members and a guinea annual subscription. Golf and tennis

contributed to the liberalisation of the middle-class Sunday; nearly half England’s

courses were open by , and nearly all by the s (although Calvinist

Scotland and nonconformist Wales resisted far longer). Cycling, boating and

motoring also played their part.

60

Douglas A. Reid

60

Jackson, Middle Classes, pp. –, –, –, , ; J. L. Garvin, The Life of Joseph

Chamberlain, vols. (London, –), pp. –, –; Newspaper Cuttings, Birmingham

Drama, vols. (Birmingham Reference Library, –); A. L. Matthison, Ladies Long Loved

and Other Essays (London, ), pp. , –; Cannadine, Lords and Landlords, p. ; Murfin,

Lake Counties, pp. ‒; G. W. Bishop, ed., The Amateur Dramatic Year Book and Community

Theatre Handbook (London, ), vol. , pp. –; New Survey of London Life and Labour, ,

pp. –; Nicholl, English Drama, pp. –; cf. Jones, Workers at Play,pp.–, and Norman

Dennis, F. M. Henriques and C. Slaughter, Coal is Our Life (London, ), p. ; John

Lowerson, Sport and the English Middle Classes, – (Manchester, ), pp. , , –,

–, ; Fraser, ‘Developments in leisure’, p. ; Helen Walker, ‘Lawn tennis’, in Mason, ed.,

Sport in Britain, pp. ‒; Dixon and Muthesius, Victorian Architecture, p. ; K. C. Edwards,

‘The Park Estate, Nottingham’, in Simpson and Lloyd, Middle Class Housing in Britain, pp. –;

James Kenward, The Suburban Child (Cambridge, ), pp. –; Jackson, The Middle Classes,

pp. (plate ), ; Rubinstein, ‘Cycling in the s’, –, cf. –, ; Graves and Hodge,

The Long Week-End, p. ; John Lowerson, ‘Golf and the making of myths’, in Grant Jarvie and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

London’s suburbs were the most enormous and socially differentiated, but

their very size and prosperity encouraged an impressive range of activities.

Moreover, leisure activities were integral to their interwar extension, as many

plots of land were reserved for tennis courts, and even golf courses were con-

structed, as developers’ inducements to house purchasers. Finally, however, as

they grew larger it became hard to say exactly when suburbs ceased to function

as suburbs and more as towns within the conurbation increasingly attracting

commercial leisure facilities: roller skating in the s, theatres and music halls

in the s, cinemas in the early s, palais de danse in the s, and ice-

skating in the thirties. Although the middle-classes included some of the most

serious critics of mass leisure, their young were among its enthusiastic

aficionados.

61

(vi)

We turn now from the indirect impact of religious sentiment on urban leisure to

the much-debated impact of industrial urbanism upon religious practice. An

early and significant religious response to the development of industrial popula-

tions may be seen in the voluntary Sunday Schools movement which com-

menced in Gloucester in and quickly spread to Manchester and other

northern and Midland industrial towns. The schools’ aims of teaching factory

children to read the Scriptures, and to withdraw them from the temptations of

the streets, were buttressed after by those ‘steam engines of the moral

world’, the religious day schools. The second major response – commencing

during the post-Napoleonic War unrest – was ‘Church extension’. Parliament

acted to remedy the discrepancies between population and Anglican places of

worship which were believed to facilitate the flourishing both of Methodism and

irreligious popular radicalism. For several decades after the pillars, spires,

towers and high-windowed gables of hundreds of new churches rose into sooty

town air, summoning their urban denizens to worship. A similar process

occurred in Scotland. Thirdly, and concurrently, there was an attempt to apply

Playing and praying

Graham Walker, eds., Scottish Sport and the Making of the Nation: Ninety Minute Patriots? (Leicester,

), esp. pp. –; R. H. Trainor, ‘The elite’, in Fraser and Maver, eds., Glasgow, , p. ;

John Guest, The Best of Betjeman (Harmondsworth, ), pp. –; Lowerson, ‘Golf ’, pp. ,

–; Richard Holt, ‘Golf and the English suburb: class and gender in a London club,

c. –c. ’, Sports Historian, (), –; Beattie, Blackburn, pp. –, , ; Wigley,

Rise and Fall of the Victorian Sunday, p. ; Mandler, Rise and Fall of the Stately Home, pp. , ,

–, , .

61

Besant, London in the Nineteenth Century, pp. , , –; Bailey, Leisure and Class, p. ; Penny

Summerfield, ‘Patriotism and empire. Music-hall entertainment –’, in John M.

Mackenzie, ed., Imperialism and Popular Culture (Manchester, ), p. ; Richardson, The Social

Dances, p. ; Jackson, Middle Classes,pp.–, ; A. A. Jackson, Semi-Detached London

(London, ), pp. –, –; John Bale, Sport and Place: A Geography of Sport in England,

Scotland and Wales (London, ), pp. , ; Graves and Hodge, The Long Week-End,p..

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

in towns the essentially rural model of pastoral ministry. The most influential

theorist of this movement was the Presbyterian Church of Scotland minister, Dr

Thomas Chalmers. Whereas the church in the countryside buttressed the social

order – using patronage and charity to invoke deference – Chalmers observed in

‘every large manufacturing city ...amighty unfilled space between the high and

the low’. This, he avowed, should be filled with systematic ‘ties of kindliness’ –

district visiting by elders and Sunday School teachers – transferring some of the

evangelical energy for foreign missions to heathens in the city of Glasgow itself.

Essentially, Chalmers sought to recreate in the manufacturing towns the ‘moral

regimen’ which he felt characterised rural society (and, indeed, smaller provin-

cial towns). Impressed by Chalmers, the evangelical John Bird Sumner (–)

set on foot a programme of lay visitations, home instruction and further school-

ing in Chester diocese (incorporating rapidly urbanising Lancashire), to over-

come ‘the general state...oftotal apathy’and ‘religious destitution’. Conversely,

one of the best-known exemplars of a vigorous urban ministry on the rural

model was the high churchman, W. F. Hook, of Coventry (-) and Leeds

(–), promoting education, sick-dispensing, and self-help institutions,

preaching the Gospel, and supporting the Ten Hour movement.

62

The subdivision of huge parishes was a necessary, though insufficient, step in

Douglas A. Reid

62

A. P. Wadsworth, ‘The first Manchester Sunday schools’, in M. W. Flinn and T. C. Smout, eds.,

Essays in Social History (Oxford, ), pp. –, –; T. W. Laqueur, Religion and Respectability:

Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture – (New Haven, ); K. D. M. Snell, ‘The

Sunday School movement in England and Wales’, P&P, (), –, esp. ; John Hurt,

Education in Evolution: Church, State, Society and Popular Education – (London, ), ch.

; Michael Sanderson, Education, Economic Change and Society in England –, nd edn

(Basingstoke, ), pp. –, –; M. H. Port, Six Hundred New Churches: A Study of the

Church Building Commission, –, and its Church-Building Activities (London, ), pp. ,

‒; A. D. Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England (London, ), p. ; Dixon and

Muthesius, Victorian Architecture, ch. ; Chris Brooks and Andrew Saint, eds., The Victorian Church:

Architecture and Society (Manchester, ), chs. , and ; Brown, Social History of Religion in

Scotland, pp. –, –; E. P. Hennock, ‘The Anglo-Catholics and church extension in

Victorian Brighton’, in M. J. Kitch, ed., Studies in Sussex Church History (London, ), pp.

–; David E. H. Mole, ‘The Victorian town parish: rural vision and urban mission’, in D.

Baker, ed., The Church in Town and Countryside (Oxford, ), pp. –; Inglis, Churches and

the Working Classes,pp.–; Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England, p. ; T. Chalmers,

The Christian and Civic Economy of Large Towns (Glasgow, –), cited in B. I. Coleman, The Idea

of the City in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London, ), pp. , –; Stewart J. Brown, Thomas

Chalmers and the Godly Commonwealth in Scotland (Oxford, ), pp. –, esp. –; Boyd

Hilton, The Age of Atonement:The Influence of Evangelicalism on Social and Economic Thought,–

(Oxford, ), pp. –; H. D. Rack, ‘Domestic visitation: a chapter in early nineteenth

century evangelism’, JEcc.Hist., (), ; Robin Gill, The Myth of the Empty Church

(London, ), p. ; M. Smith, Religion in Industrial Society (Oxford, ), pp. , ‒ff.;

H. W. Dalton, ‘Walter Farquhar Hook, Vicar of Leeds: his work for the Church and the town,

‒’, Publications of the Thoresby Society.Miscellany, (), –; Sheridan Gilley, ‘Walter

Farquhar Hook, vicar of Leeds’, in Alastair Mason, ed., Religion in Leeds (Stroud, ), pp. –;

David E. H. Mole ‘Challenge to the Church. Birmingham, –’, in Dyos and Wolff, eds.,

The Victorian City, , pp. –, , .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

this process of Anglican revitalisation. Thus evangelicals also initiated societies

of volunteer lay workers, such as the Religious Tract Society, or District

Provident Societies. In in Glasgow, and more generally from , extra-

parochial, inter-denominational City Missions were established systematically to

encourage Bible reading, and conversion. Thrift, providence, hygiene and self-

improvement were taught as necessary preconditions for living a Christian life.

The realisation of the depth of popular alienation in the s and s lent

urgency to this work, resulting in the employment of professional workers, and

attacks on pleasure fairs and Owenite ‘Infidels’.

63

The participation of nonconformists in City Missions illustrates the mitiga-

tion but not the elimination of the fierce rivalries between the establishment and

dissent. Some Congregationalists and Unitarians developed their own impres-

sive auxiliaries, doing the kind of mission and charity work which characterised

the Anglican parochial ideal, as at Carr’s Lane in Birmingham. They also

addressed the general education of their members through ‘mutual improvement

societies’, and, portentously, in the s the more rationalist denominations like

the Unitarians established explicitly recreational offshoots, planting seeds which

were to flourish dramatically in the second half of the century. The way had

been shown by the Sunday Schools through their Whit Walks, anniversary fes-

tivals and railway excursions (from the very inception of the Liverpool to

Manchester line in ). But it was in the s that chess, singing classes,

musical entertainments, tea parties, excursions, even dances, were developed for

adult members, to meet a desire for social fellowship and as a counterforce to

commercial entertainment, and to ‘moralise’ the working people it was hoped

to evangelise. A readiness to embrace recreation for religious purposes was

limited at this stage by the continuing influence of puritanism, but it was also

reflected in the foundation of Bands of Hope, providing rational recreation for

children as a prophylaxis against intemperance, and the YMCA, directed at the

salvation of young shopworkers. The specialised nature of both organisations

reflected the increasing complexity of urban society.

64

How effective were these decades’ work in dealing with religious ‘destitu-

tion’? The unique official census of religious attendance in offered little

Playing and praying

63

Lewis, Lighten their Darkness, pp. , –, , , –, –; E. R. Wickham, Church and

People in an Industrial City (London, ), p. ; Geoffrey Robson, ‘The failures of success:

working class evangelists in early Victorian Birmingham’, in D. Baker, ed., Religious Motivation

(Studies in Church History, , Oxford, ), pp. –; Brown, Social History of Religion in

Scotland, pp. , , –, ; Edward Royle, The Victorian Church in York (York, ), pp. ‒.

64

VCH, Warwickshire, ; W. B. Stephens, ed., The City of Birmingham (London, ), p. ; cf.

Cox, The English Churches in a Secular Society, pp. –; Reid, ‘Labour, leisure and politics’, pp.

–; Barry Haynes, Working Class Life in Victorian Leicester (Leicester, ); D. A. Reid,

‘Religion, recreation and the working class: Birmingham –’, Bulletin of the Society for the

Study of Labour History, (), ; Lilian L. Shiman, ‘The Band of Hope movement: respect-

able recreation for working-class children’, Victorian Studies, (), –; C. J. Binfield,

George Williams and the YMCA (London, ), chs. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

encouragement. Depending on interpretation, it suggests that between and

per cent of the British population were in church on census Sunday. Today

this would be remarkable, but most agreed with census commissioner Horace

Mann that it signified an ‘alarming’and ‘sadly formidable’proportion of the pop-

ulation were ‘habitual neglecters’ of public worship. As the middle classes were

‘distinguished’ by their devotions, and the upper classes ranked regular church

attendance as ‘amongst the recognized proprieties of life’, most of the missing,

Mann opined, belonged to ‘the labouring myriads’ or ‘artizans’, who comprised

an ‘absolutely insignificant’ portion of the congregation, ‘especially in cities and

large towns’. What were the causes? ‘Social distinctions’, as manifested particu-

larly in pew rents, made it difficult to overcome the already profound gulf sep-

arating ‘the workman from his master’. Similarly, differences in social ‘station and

pursuits’ led to cynicism regarding the clergy. Even more profoundly, the ‘social

burdens’of ‘the poor’, particularly ‘the vice and filth which riot in their crowded

dwellings’, denied opportunities for religious reflection: ‘the masses of our

working population . . . the skilled and unskilled labourer alike . . . hosts of minor

shopkeepers and Sunday traders . . . and . . . miserable denizens of courts and

crowded alleys’ were ‘engrossed by the demands, the trials or the pleasures of the

passing hour, and ignorant or careless of a future’. However, although this led to

‘a genuine repugnance to religion itself ’, there remained ‘that vague sense of

some tremendous want, and aspirings after some indefinite advancement’ which

offered an opportunity to a more ‘aggressive’missionary activity by the churches.

Mann cited the ‘zeal and perseverance’ of Methodists and Mormons and street

preaching. Hence there were solutions which went beyond the obvious one of

removing pew rents. ‘Ragged Churches’ and mission halls could be built where

there would be ‘a total absence of all class distinctions’, lay preachers could be

used to confound suspicion of clergy motives, the religious contribution to

charity could be more overt and, above all, measures taken to improve housing.

All these would be more sensible than construction work, for, already, ‘teeming

populations often . . . surround[ed] half empty churches’.

65

How valid was Mann’s characterisation of the cities as black holes for the

churches? Post-war scholars were in no doubt. E. R. Wickham’s study of

Sheffield claimed that alienation of the urban working-class population from the

Douglas A. Reid

65

W. S. F. Pickering, ‘The census – a useless experiment?’, British Journal of Sociology, (),

, ; David M. Thompson, ‘The religious census of ’, in Richard Lawton, ed., The

Census and Social Structure: An Interpretative Guide to Nineteenth Century Censuses for England and

Wales (London, ), p. ; Michael R. Watts, ed., Religion in Victorian Nottinghamshire: The

Religious Census of , vols. (Nottingham, ), vol. , p. xiv; for the most recent guide to the

literature on see Clive D. Field, ‘The religious census of Great Britain: a bibliograph-

ical guide for local and regional historians’, The Local Historian, (), –; PP –

, Census , Religious Worship [England & Wales], pp. clviii–clxii. For recent ques-

tioning of the effectiveness of home missions see M. Hewitt, ‘The travails of domestic visiting:

Manchester, –’, HR, (), –, .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

churches existed ‘from the time of their very emergence in the new towns’. The

‘index of attendance’ devised by K. S. Inglis stood at for small towns and rural

areas as compared with only for ‘large towns’, and Inglis followed Mann in

arguing that ‘the absent millions lived in large . . . industrial towns’.

Subsequently, Harold Perkin concluded that ‘the larger the town the smaller the

proportion of the population attending any place of worship; and . . . the larger

the town, with the exception of London, the smaller the proportion of Anglican

to all attenders’. Like Chalmers, Perkin related working-class indifference to the

decline of social dependency in towns, and he believed migrants drifted from

rural Anglicanism to nonconformity in small towns, and to indifference in cities.

This historiographical trend was reinforced by A. D. Gilbert’s work which

emphasised a deep link between urbanisation and ‘institutional secularisation’.

66

However, this consensus was challenged in the s, and much subsequent

work has followed a revisionist line, doubting whether the influence of urban-

isation on religion was so sweeping as had been assumed. Hugh McLeod util-

ised the and subsequent unofficial newspaper censuses from the s to

argue the primacy of regional and status-system distinctions over simple

rural/urban distinctions. Scepticism about urbanisation’s effects was stated most

trenchantly by Callum Brown in , who utilised regression analysis to suggest

that there was ‘no statistically significant relationship between churchgoing rate

and population size or growth for towns or cities’ in England and Wales in .

Nor, he argued, was population size of statistical significance for Scottish atten-

dance. Similarly, K. D. M. Snell’s investigation of the North Midland figures for

found only small, rather unconvincing, correlations between urbanisation,

industrialisation and low overall religious attendance.

67

Yet, in , Steve Bruce fundamentally questioned the statistical validity of

Brown’s case – explaining that the divergence of his regressions from Brown’s

was a consequence of the application of more reliable procedures and, particu-

larly, of Brown’s failure to allow for the distortion caused by the unique case of

London. Bruce argues that his results essentially reaffirm the message given by

the work of Wickham and Inglis. Thus, Brown’s statistical case must currently

be regarded as ‘not proven’. However, this critique of the statistical basis of

Playing and praying

66

Wickham, Church and People in an Industrial City,pp., –, –; Inglis, Churches and the

Working Classes, pp. –ff; Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society, –

(London, ), pp. , ; Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England, pp. viii, ; see

also K. S. Inglis, ‘Patterns of religious worship in ’, JEcc.Hist., (), ; Pickering, ‘The

census – a useless experiment?’, –; Chadwick, The Victorian Church, , p. ; R. B.

Currie, A. D. Gilbert, and Lee Horsley, Churches and Church-Goers: Patterns of Church Growth in

the British Isles since (Oxford, ), pp. ff.

67

H. McLeod, ‘Class, community and region: the religious geography of nineteenth-century

England’ in M. Hill, ed., A Sociological Yearbook of Religion in Britain (London, ), pp. , –,

–, n. ; C. G. Brown, ‘Did urbanisation secularise Britain?’, UHY (), –; K. D. M.

Snell, Church and Chapel in the North Midlands (Leicester, ), pp. , –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

revisionism has yet to be widely appreciated. Partly, no doubt, this is because

work on regional sources has continued to show support for the revisionist case.

Thus Robin Gill used Episcopal Visitation Returns to show that churchgoing

in twelve large towns – including seven cotton factory towns – even grew during

-, the fastest period of urban growth. And Mark Smith’s study of the

classic industrialising district of Oldham and Saddleworth showed that the efforts

of a vigorous evangelical clergy bore fruit in an impressive per cent of the eli-

gible population attending church in .

68

All in all it is too sweeping to characterise cities and large towns as essentially

hostile to religion; regional and class analysis offers a more convincing explana-

tion of the relationship between urbanisation and churchgoing in Britain in the

nineteenth century. In , attendances were highest in England south of the

line from the Severn to the Wash, which were also the areas of greatest Anglican

strength, where squire and parson joined hand in hand to try to dominate the

mental, as well as the material, universe of the farm labourer. Within these areas,

with the important exception of London, towns and cities generally had higher

rates than the average for all cities: some were high-status cathedral cities, health

resorts and county towns like Bath, Gloucester and Hastings (with many inhab-

itants concerned about the ‘proprieties of life’) but they also included Plymouth

and Bristol. This once again suggests the importance of continuities between

country and city. Deriving initially from the high proportion of immigrants who

made up burgeoning urban populations, such continuities are also illustrated by

urban superstitions and rituals matching those found in the countryside, and

important to some popular religiosity in London even in the s. Conversely,

church attendance was generally weakest in the numerous industrial towns and

townships situated in the large upland parishes of the Midlands and North, and

lacking the social compulsions associated with southern landed estates. Thus the

towns of lowest attendance were low-status industrial towns such as Birming-

ham, the Potteries and Sheffield; and most towns in Lancashire, the West Riding

and the mining towns of the North-East were well below their regional aver-

ages. Nevertheless, some, like the Black Country towns and the Welsh industrial

towns of Wrexham and Llanelli stood well above them – local factors, such as

evangelistic blitzes on the exploited workforces of the Black Country, could

affect regional patterns.

69

Douglas A. Reid

68

Steve Bruce, ‘Pluralism and religious vitality’, in S. Bruce, ed., Religion and Modernisation (Oxford,

), pp. –; Gill, The Myth of the Empty Church,pp., –, , ; Smith, Religion in

Industrial Society, pp. ‒, .

69

McLeod, ‘Class, community and region’, pp. –; cf. John D. Gay, The Geography of Religion in

England (London, ), pp. –; Paul S. Ell and T. R. Slater, ‘The religious census of : a

computer-mapped survey of the Church of England’, Journal of Historical Geography, (),

–; C. G. Brown, ‘The mechanism of religious growth in urban societies. British cities since

the eighteenth century’, in H. McLeod, ed., European Religion in the Age of Great Cities (London,

), pp. –; Sarah Williams, ‘Urban popular religion and the rites of passage’, in McLeod,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Nonconformity had been the most popular religious tradition in towns in

, and was even more so by the s, when nearly six in ten attenders were

chapelgoers; only Bath and Hastings had more than half of their congregations

in Anglican churches. Nevertheless, the Church of England remained the largest

single denomination in most other towns and cities, reflecting its historical

centrality. The major nonconformist groups (Wesleyan Methodists, Baptists

and Congregationalists) outstripped the Anglicans in Leicester, Burnley and

Bradford, but groups with humbler adherents, like the Primitive Methodists,

were relatively weak in urban areas, except in Hull (the missionary headquarters

of its joint-founder, William Clowes), and Scarborough (its outpost up the

coast). Roman Catholicism was strongest in Liverpool (where it was the largest

denomination) and in other areas in the West Midlands and North-West most

subject to Irish immigration like Warrington, the Potteries and Barrow-in-

Furness.

70

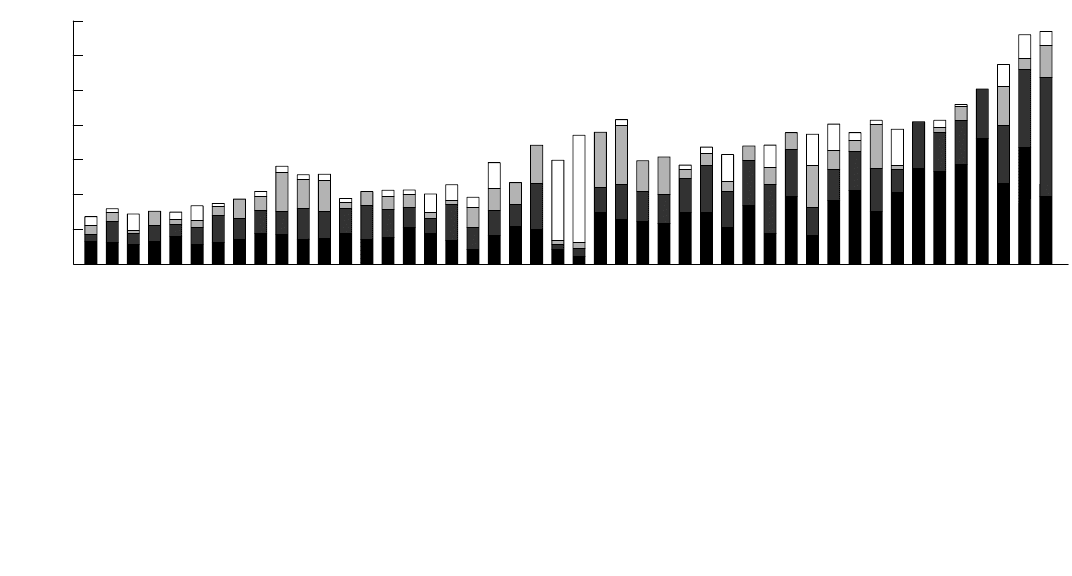

If there was no simple relationship between religious attendance and the size

of towns, marked contrasts within urban areas firmly support the notion of a clear

relationship between religion and class. Towns were not undifferentiated wholes.

Hence, as McLeod pointed out, in the s’ newspaper censuses low-status dis-

tricts within cities had much lower church attendances than their high-status

counterparts. Thus, elegant Edgbaston and insalubrious Saltley were very

different within the overall ‘Anglican’ city of Birmingham, which had very low

attendance rates (like the region of which it was part). Classy Clifton and ‘poor

and populous’ St Philip and St Jacob, had contrasting, though high, rates, like

their city, Bristol, and its region (compare numbers , , and on Figure

.). For similar reasons there were also important correspondences as regards

denominational allegiances between high- and low-status areas of different

towns. As Figure . suggests, attendance in high-status districts, wherever they

were, tended disproportionally towards the established church (above all, in the

examples given, in Birmingham’s Moseley district, and in Hampstead), and

towards the major nonconformist churches (in East Leicester particularly). By

contrast, in low-status (working-class) areas Anglicanism was noticeably less

Playing and praying

ed., European Religion,pp., –; Sarah C. Williams, Religious Belief and Popular Culture in

Southwark, c. – (Oxford, ); Geoffrey Robson, ‘Between town and countryside:

contrasting patterns of church-going in the early Victorian Black Country’, in Baker, ed., The

Church in Town and Countryside, pp. –.

70

Inglis, ‘Patterns of religious worship in ’, ‒; McLeod, ‘Class, community and region’, pp.

‒; Gill, The Myth of the Empty Church, p. ; Hugh McLeod, Religion and Society in England

– (London, ), p. ; Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England, pp. –; H. B.

Kendall, The Origin and History of the Primitive Methodist Church (London, ), vol. , pp.

–, , pp. –, –, –; Stubley, A House Divided, pp. –, ; Clive Field, ‘The

social structure of English Methodism, eighteenth-twentieth-centuries’, British Journal of Sociology,

(), ‒; David Hempton, The Religion of the People (London, ), p. ; McLeod,

‘New perspectives on Victorian working-class religion’, –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

B’ham: St Bart., St Mary, St Stephen 1

B’ham: Duddesdon, Nechells, Saltley 2

Sheffield North 3

Sheffield: Park 4

London: St George’s in the East 5

London: Shoreditch 6

Bradford: North, South & Bradford Moor 7

Bradford: East & West Bowling 8

Nottingham: North-East 9

Leicester: North & Middle St Margaret’s 10

Sheffield: Brightside 11

Sheffield: Attercliffe 12

B’ham: Aston Manor 13

B’ham: Bordesley & Balsall Heath 14

London: Poplar 15

London: Battersea 16

Liverpool: West Derby 17

Liverpool: Kirkdale 18

The Potteries: Hanley 19

The Potteries: Longton 20

Portsmouth: Kingston 21

Nottingham: Basford & Bulwell 22

Liverpool: Scotland 23

Liverpool: Exchange & Vauxhall 24

Bristol: Bedminster 25

Bristol: St Philip & Jacob 26

Sheffield: Eccleshall 27

Sheffield: Nether Hallam 28

London: Lambeth 29

London: Hackney 30

Liverpool: Toxteth 31

B’ham: Handsworth 32

Bradford: Little & Gt Horton 33

Bradford: Manningham 34

The Potteries: Burslem 35

The Potteries: Stoke 36

Portsmouth: Gosport 37

Nottingham: North-West 38

B‘ham: Edgbaston & Harbome 39

B‘ham: Moseley & King’s Heath 40

London: Hampstead 41

London: Lewisham 42

Portsmouth: Southsea 43

Liverpool: Abercromby 44

Bristol: Clifton & Westbury 45

Leicester East St Mary & East St Margaret 46

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Percentages

Figure . Urban religious differentiation: attendance rates in selected areas

–⫽ low-status areas

–⫽ mainly working-class areas

–⫽socially mixed areas

–⫽ high-status areas

Source: drawn from data in H. McLeod, ‘Class, community and region; the religious geography of nineteenth-

century England’, in M. Hill, ed., A Sociological Yearbook of Religion in Britain (London, ), pp. –.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

popular, and minor nonconformity was correspondingly stronger. Thus, major

differences within urban areas certainly vindicate Mann with regards to the

importance of class, and such findings are borne out by other detailed local

studies of different parts of London. However, it is worth noticing that the

strength of Roman Catholicism also implies the importance of religion as a

symbol of national or sectarian rather than class identity – a factor which may

also help to explain some of the social reach of Protestantism in Lancashire, and

the vitality of separate Protestant and Catholic Whit Walks.

71

(vii)

If class was the main factor conditioning non-churchgoing, how effective were

the proposed solutions? Pew rents were both the immediate cause and symptom

of the deeper social distinctions, argued Mann. There was much to this analy-

sis, particularly in relation to the poorest, but the problem was not straightfor-

ward. Some form of income generation was an economic necessity (especially

for the non-established churches lacking endowments), and pew rents were hal-

lowed by time, and legitimate within the framework of an unequal society of

ranks. Thus in Oldham and Saddleworth rents could be very low (a farthing per

quarter in Saddleworth before ), were sometimes not rigidly enforced, and

those who rented the cheaper pews felt that they were establishing their place in

the parish. From this perspective it was not so shocking that per cent of seats

in English churches in were pew rented. However, rents were heavily crit-

icised from the s, by both evangelicals and Tractarians, as an ‘intrusion of

human pride’ into God’s House, and a reform campaign resulted, with early suc-

cesses in Chesterfield, Pimlico and Clerkenwell. These criticisms represented a

realisation – hastened by Chartist demonstrations early in the decade – that many

had come to resent deeply such overt markers of their inferiority. The effect of

class society was exemplified graphically by the case of the Glasgow ‘city

churches’ of the Church of Scotland where pew-renting arrangements moved

from being socially inclusive to exclusive in the first decades of the century.

Middle-class demand pushed up the average rent to half-a-guinea for six months

by – – a trend reinforced by greater middle-class sensitivity to personal

hygiene – and cheap seats were abandoned. It is easy to see how pew renting

could alienate, though there was self- as well as enforced exclusion. Thus, even

where new free seats were provided in other Glasgow churches poor parishion-

ers rejected them – especially those who had known better times, and who

Playing and praying

71

McLeod, ‘Class, community and region’, pp. ‒; The Churchgoer, Being a Series of Sunday Visits

to the Various Churches of Bristol (Bristol, edn), pp. –; cf. Thompson, ‘The religious census

of ’, pp. –; Cox, The English Churches in a Secular Society, pp. –; Joyce, Work, Society

and Politics, pp. –; Neville Kirk, The Growth of Working Class Reformism in Mid-Victorian

England (London, ), ch. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008