Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

built during the late Muromachi and Momoyama

periods. For security, builders developed walls of

enormous boulders that often had smooth surfaces

that would be difficult to scale. Moats (hori) also pro-

vided a means to deter an attacking force.

The castle was not only a means of defense, but

also served as the hub of administration and com-

merce in the domain. Castles housed the domain

lord and chief retainers. Towns developed around

the structures, called “towns beneath the castle”

(jokamachi) since the castle was often elevated, and

both literally and figuratively overshadowed all

other buildings nearby. Merchants and artisans

became an important aspect of life in these castle

communities, as daimyo and their retainers had

more time and disposable income than in the past.

Further, the rise of fashion and interest in display (in

the sense of decoration and adornment) that arose in

the cosmopolitan Edo period made it necessary for

members of the warrior class to keep up appear-

ances, and this led to healthy economic growth even

in provincial castle towns. Castle construction is sur-

veyed in detail in chapter 10: Art and Architecture.

WARRIOR RANKS AND

HIERARCHY

Military Structure

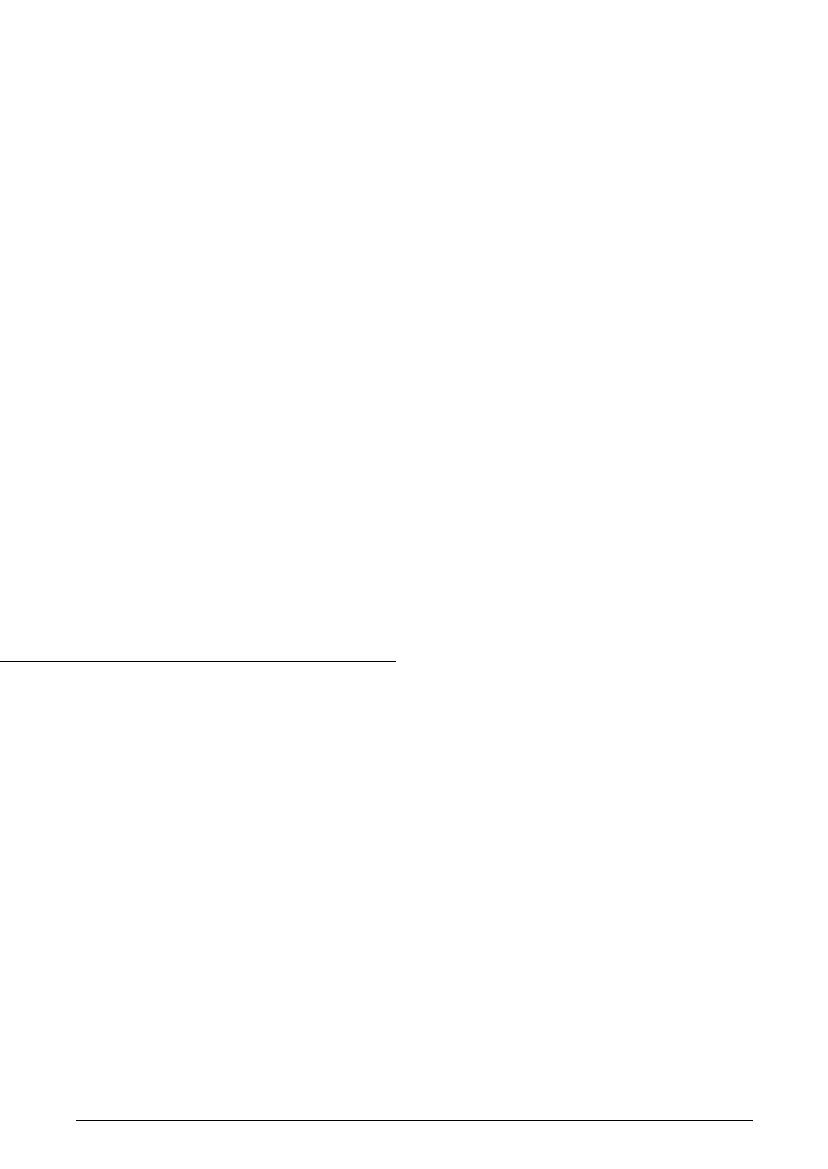

From the late Muromachi era, army organization

changed significantly. One positive outcome of the

long era of internecine battles was a more clearly

defined military order. While the shogun still func-

tioned as the head of the military government as

well as the supreme general, military structure

emerged as the basis for the socioeconomic hierar-

chy and also for the organization of armed forces. As

in the ritsuryo system of conscripted military first

instituted in the Nara period, the leaders of warrior

bands still usually came from aristocratic back-

grounds. Also as in the previous system, warriors of

status were mounted, as equestrian soldiers had

higher status than infantry. Increasingly, however,

figures of more humble social rank began to ascend

to military positions previously reserved for aristo-

crats, especially as the country approached unifica-

tion under the charismatic leaders Oda Nobunaga

and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, both of whom initially

held ashigaru (foot soldier) ranks. Thus, military

organization began to reflect the new ethos of war-

rior culture, in which martial ability could confer

status that had previously been inherited.

Some daimyo administrated armies with a basic

structure. For example, in the Muromachi period,

Hojo Ujiyasu separated his bodyguards into 48

squads and placed a captain in command of each

squad. These squads were then divided into seven

companies. Six companies were composed of seven

squads in total, and one company had six. Finally,

each squad numbered 20 men. Tokugawa Ieyasu also

favored dividing warriors into companies. Initially,

his elite oban (great guard) force was separated into

three companies. With the advent of the Korean

invasion, the army numbered five companies, and by

1623, Ieyasu’s force consisted of 12 companies. The

companies were headed by a single captain, four

lieutenants, and 50 guards.

There was extensive variation in the ways troops

were structured for battle and the hierarchy of com-

mand that directed the troops. See the chart on page

175 for a typical configuration.

It should be noted that horse-mounted troops

were also sometimes deployed, but from the late

medieval period onward this practice became more

and more infrequent.

Warrior Service

Requirements

In medieval times, daimyo raising an army calcu-

lated warrior wealth in order to determine the

amount of service, including numbers of mounted

and foot soldiers, each vassal would provide. From

the Momoyama period, warrior service was mea-

sured in koku, a unit of measure that was based upon

the amount of unpolished rice normally required

annually for sustenance—approximately 5.12 U.S.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

174

W ARRIORS AND W ARFARE

175

bushels or 180.39 liters. This figure was then used to

assess average annual yields of a rice field within a

system of four grades: 1.5, 1.3, 1.2, or 1.1 koku annu-

ally for each 10th of a hectare (or quarter-acre). The

koku quantity, known as kokudaka, or assessed tax

base measured in koku, replaced an earlier system

used in the Kamakura and Muromachi periods that

calculated annual tax in terms of monetary value.

In 1649, for instance, samurai of hatamoto rank

with assets of 300 koku would be required to provide

one spearman, an armor-bearer, a groom, a sandal

bearer, and a hasami-biko bearer as well as one bag-

gage carrier to his lord whenever called upon for

service. While hatamoto was a relatively humble

rank, providing service to the shogunate was a pri-

mary measure of loyalty among the warrior classes,

and thus a critical cost of allegiance. Prior to the

Edo period, there was little standardization of the

service requirements incurred by a vassal, although

certainly some vassals were taxed more heavily than

others. The most unfortunate among the military

ranks were obligated to fulfill the multiple demands

of temples, shrines, and aristocratic owners of

provincial estates (shoen).

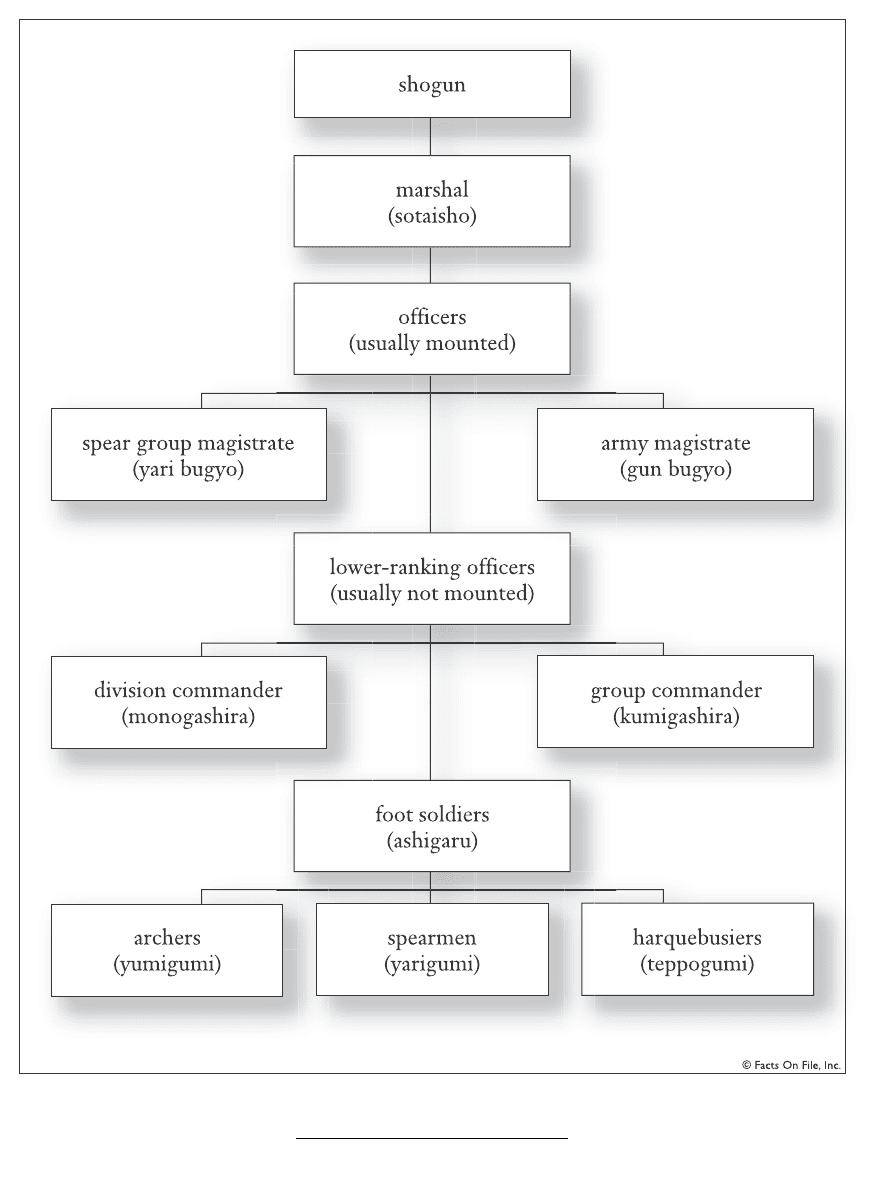

Warrior-Monks (Sohei)

Armed forces known as sohei (warrior-monks)

mounted a potent challenge to aristocrats and war-

riors throughout the feudal era. The term akuso,

meaning evil monks, found in diaries of Heian-

period courtiers, summarizes the general view of

these soldiers that represented powerful temples.

While warriors and aristocrats struggled for control

of feudal Japan, from the sidelines the sohei fought to

unseat both of these forces and instead obtain both

land and wealth for the benefit of powerful religious

institutions.

The origins of the bands of warrior-monks and

the language used to identify these figures can be con-

fusing. For example, the title warrior-monk (the more

common English translation of the term sohei) carries

varied connotations in different periods, and sohei

were not always part of the monastic order at the tem-

ples they served. Further, sohei were well armed and

skilled in the use of weapons, despite Buddhist pre-

cepts prohibiting monks from engaging in such pur-

suits. In addition, civil codes that limited weapons

possession among priests, acolytes, and other clerics

had little effect on the many sohei who functioned in

institutions not subject to such restrictions. Another

common misconception about warrior-monks also

relates to terminology. Some scholars have conflated

the roles of sohei and yamabushi (mountain ascetics),

since both of these religious figures dwelt in moun-

tains and are sometimes identified in medieval

sources as similar figures. Despite the apparent simi-

larity to the word bushi, which is also used to desig-

nate samurai, the “bushi” in yamabushi is written with

a different character than the “bushi” for warrior. The

term yamabushi distinguishes ascetics who engaged in

mountain pilgrimages and sustained meditation as

part of their spiritual practice. However, many pow-

erful temples were located on mountains, and while

yamabushi also occupied such territory, they were usu-

ally benign figures devoted to solitary religious prac-

tice. At the same time, the legions of warrior-monks

enlisted by religious institutions were only occasion-

ally referred to as yamabushi in contemporary sources,

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

176

5.9 Buddhist warrior-monk (sohei) (Illustration

Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken kojitsu, mid-19th century)

simply because the temples they served were in

mountainous locations.

Temples and other religious institutions were

motivated to deploy units of warrior-monks to

defend land acquired during the redistributions and

lapses in administration practices on provincial

estates that occurred in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Young warriors employed by private estates as militi-

amen confused matters by shaving their heads and

were often mistaken for sohei in practice and in his-

torical accounts. In some cases, the warrior-monks

(including those private soldiers who appeared to be

monks, but often were not) became so powerful that

they posed a threat to the imperial court and the

shogunate. Warrior monks serving Enryakuji, Kofu-

kuji, and Miidera, all temples located near Kyoto or

the old capital, Nara, were particularly notorious.

With the burning of Enryakuji by Oda Nobu-

naga in 1571, the power of the sohei diminished sig-

nificantly. Efforts mounted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi

and the weapons prohibitions instituted in the late

Momoyama and early Edo periods finalized the sup-

pression of these warriors.

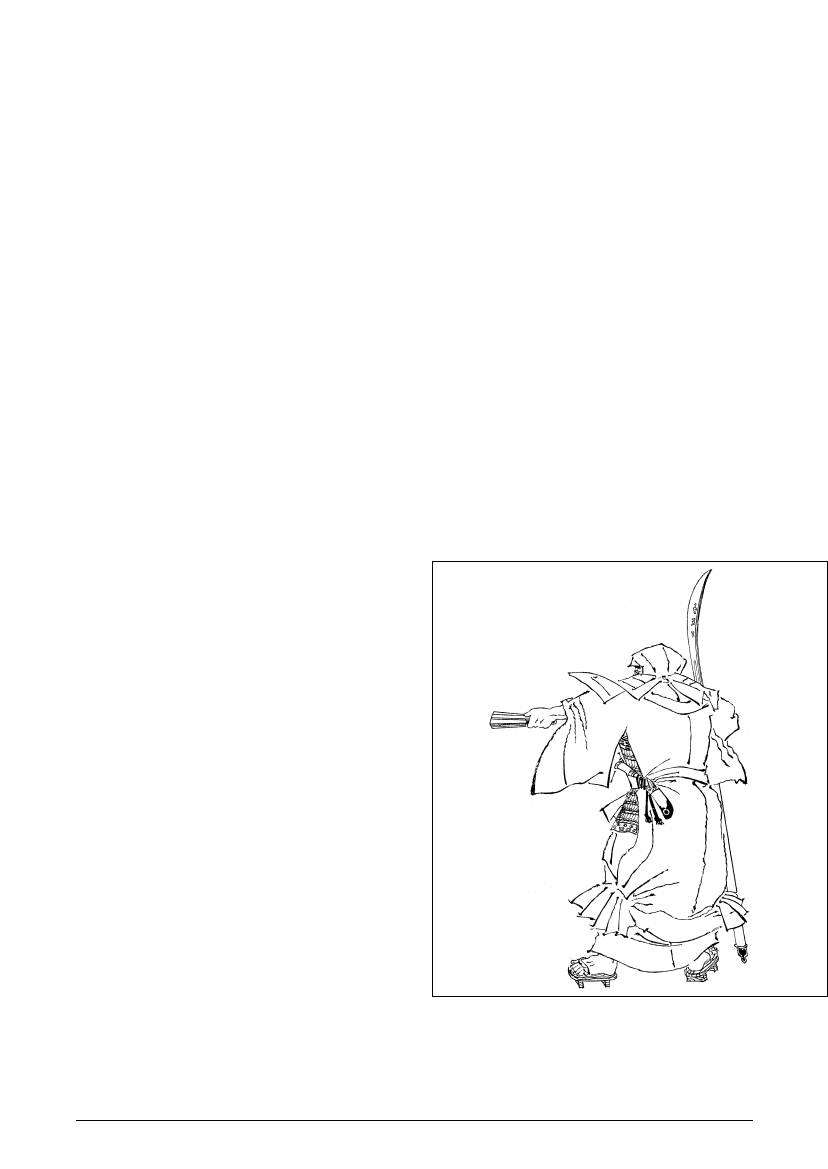

Foot Soldiers (Ashigaru)

The term ashigaru (literally, “light of foot”) was used

for foot soldiers, or infantry, from the Muromachi

through Edo periods. These soldiers first attained a

reputation during the Onin War (1467–77) when,

along with nobushi (armed peasants) and akuto (ban-

dits), they laid waste to the capital city, Kyoto. Foot

soldiers were inexpensive to outfit, and because

these warriors had little equipment, such as armor,

they could move rapidly. Subsequently, as constant

warfare ensued during the Warring States period,

they came to be more prominent in daimyo armies,

and were outfitted more completely.

From the start, ashigaru weapons consisted of

bow and arrow or pole-mounted arms (naginata, and

later, yari). Once firearms were introduced in 1543,

ashigaru played an increasingly prominent role in

warfare and were often organized into musketeer

units (teppo ashigaru or teppogumi ashigaru). By the

beginning of the Edo period, ashigaru were granted

positions as the humblest samurai, certainly an

improvement upon their initial social rank.

Attendants (Yoriki

and Doshin)

Even samurai of comparatively low social status

were accompanied by attendants who furnished

armor and supplies, tended to weaponry and horses,

and provided protection. Figures who performed

these assistant functions were called yoriki (literally,

“strength that is offered”) and doshin (literally, “like-

minded” or “shared hearts”). These figures were

usually considered members of the warrior class in

the sense that they were also professional soldiers.

In the early medieval period, when their services

were not needed in battle, attendants were likely to

be engaged in farming activities. By the Muromachi

W ARRIORS AND W ARFARE

177

5.10 Kamakura-period foot soldier (Illustration Kikuchi

Yosai from Zenken kojitsu, mid-19th century)

period, yoriki was a term used for samurai who

served warrior-commanders of higher rank—proof

of the social mobility possible in the warrior class

during feudal times. From the 16th century, yoriki

were usually mounted samurai in command of other

samurai or ashigaru. Under Tokugawa rule, yoriki

managed patrol and guard units composed of doshin.

Considered members of the gokenin category of vas-

sals, both yoriki and doshin were ranked above ordi-

nary peasants, but yoriki claimed higher hereditary

status and accordingly merited larger family

stipends. Therefore they were entrusted with more

important military duties than doshin. In the Edo

period, doshin (along with meakashi, military agents)

were members of police forces in both the capital

and smaller castle towns.

Masterless Samurai (Ronin)

The term ronin (literally, “floating men”) is most

commonly used to designate masterless samurai of

the Edo period. A samurai became masterless for a

variety of reasons including the death of the master—

whether of natural causes or in battle—or because he

abandoned his master as a samurai. However, as early

as the Muromachi period, the word ronin was used to

refer to warriors who became separated from their

commanders and/or warrior stipends.

One of the most dramatic events for many ronin

was the Battle of Sekigahara (1600) after which as

many as 400,000 warriors became “floating men” due

to the defeat or demise of many daimyo and other

chieftains. Another effect of the events at Sekigahara

was redistribution of lands held by samurai, leaving

many warriors with no residence, no livelihood, and

no supporting forces. Estimates indicate that some

100,000 disgruntled ronin joined the forces of Toy-

otomi Hideyoshi’s heir, Hideyori, at Osaka Castle and

fought during the siege of 1614–15. However, many

masterless samurai also joined the ranks of Tokugawa

Ieyasu, and some were rewarded with government

positions and stipends when Ieyasu prevailed at

Osaka. Other former samurai left behind their mili-

tary vocation and sought work in provincial castle

towns or adopted new professions in the rapidly

growing cities of the Edo period.

Figures who remained ronin presented a chal-

lenge to the Tokugawa shogunate. As marginalized

former military men, their dissatisfaction with their

position led to uprisings, such as the Keian Incident

in 1651. Some former samurai turned their attention

to instruction in martial arts, or theorized about the

philosophy of the warrior. In some cases, the Toku-

gawa shogunate attempted to stimulate employment

of such figures. Eventually many samurai without

masters abandoned their status or simply left no

heirs. A small number of ronin earned their marginal

role through criminal activities. In 1703, the 47

Ronin Incident caused further disorder in the Toku-

gawa government as a group of masterless samurai

mounted an act of revenge in response to the per-

ceived unjust death of their lord and were punished

by the shogunate for this murderous act. The 47

ronin were then ordered to commit seppuku. See

“Model Warrior Values—Values Expressed in Life—

Loyalty” (pp. 145–146) for additional information.

BATTLE TACTICS

A wide range of battle tactics was used by samurai over

nearly 700 years of medieval and early modern history.

Warrior strategies in battle were determined in part by

the weapons used and the topography of the battle site

or domain where the campaign was conducted. In

most geographical locations feasible for battle, such as

open plains, cavalry were quite effective. However,

Japanese topography includes inhospitable areas

where archers on foot—and later, firearm units—were

better suited to battles in these mountainous, heavily

forested, or rocky terrains. Further, the size and

degree of specialization of troops affected the military

techniques employed by officers, and these factors also

varied as the warriors of Japan encountered changing

political and economic circumstances.

Training

By definition, a samurai was a professional soldier

and devoted hours to preparing for warfare. Battle

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

178

preparations encompassed a range of activities,

including mental as well as physical exercises. War-

riors were encouraged to formulate a philosophy

regarding death, and most retainers incorporated

aspects of contemporary Buddhist and Confucian

thought into their disciplined attitude toward life,

danger, and death. The legendary samurai integrity

essential to the code of behavior known as Bushido

(literally, “the way of the warrior”—for additional

information on Bushido see above) derived in part

from the powerful sense of personal responsibility

assumed by self-reliant medieval warriors. In

medieval times, retainers first drew upon their own

resources to outfit and train military units, and later

became dependent upon daimyo or other higher-

ranking lords for support. Samurai training thus

reflected the investment of a warrior’s patron or lord

as well as the individual samurai’s dedication to self-

improvement. Generally, during the nearly 700

years of medieval and early modern Japanese history

dominated by warrior culture, samurai trained in

various applied skills using the tools and principles

of warfare, from basic battle maneuvers to martial

strategy, and also investigated the ethical founda-

tions of warfare.

Medieval warriors were able to train with

instructor-opponents only if they had aristocratic

rank or high social standing. Before the Edo peace,

large numbers of peasants joined the ranks of the

military in the Warring States period during the

15th and 16th centuries with little or no military

background. These foot soldiers, or ashigaru,

required schooling in traditional samurai mental dis-

cipline as well as intensive instruction in military

maneuvers. In addition to individual exercises, foot

soldiers participated in regiment drills, which

endeavored to transform individual soldiers into a

well-coordinated unit that operated in unison on the

battlefield. In the latter part of the Muromachi and

into the Azuchi-Momoyama period, foot soldiers

were required to practice by following a mounted

general through battle formations and attack-retreat

sequences before they were permitted to pick up

their weapons to fight. In the Edo period, wealthy

and elite samurai participated in martial arts drills

focusing on stances and motions both with and with-

out weapons. Retainers from the warrior class alone

were entitled to pursue the martial arts during the

Edo period. However, such activities became more a

form of sport inspired by pride in military spirit

rather than true combat training, as there was no

arena for combat under Tokugawa rule.

Shield Deployment/

Formations

In encounters staged on open ground or slightly

mountainous terrain, warriors used temporary forti-

fications like those discussed above. However, such

building projects required significant resources, and

rapid solutions were more likely to bring favorable

results. In preparing for some battles, samurai

armies arranged connected shields in a formation

called kaidate designed for mobility. Linked wooden

shields were an effective impediment to the progress

of an oncoming opponent, much like temporary for-

tifications such as the stacked brush barriers called

sakamogi, especially when conflicts took place on

W ARRIORS AND W ARFARE

179

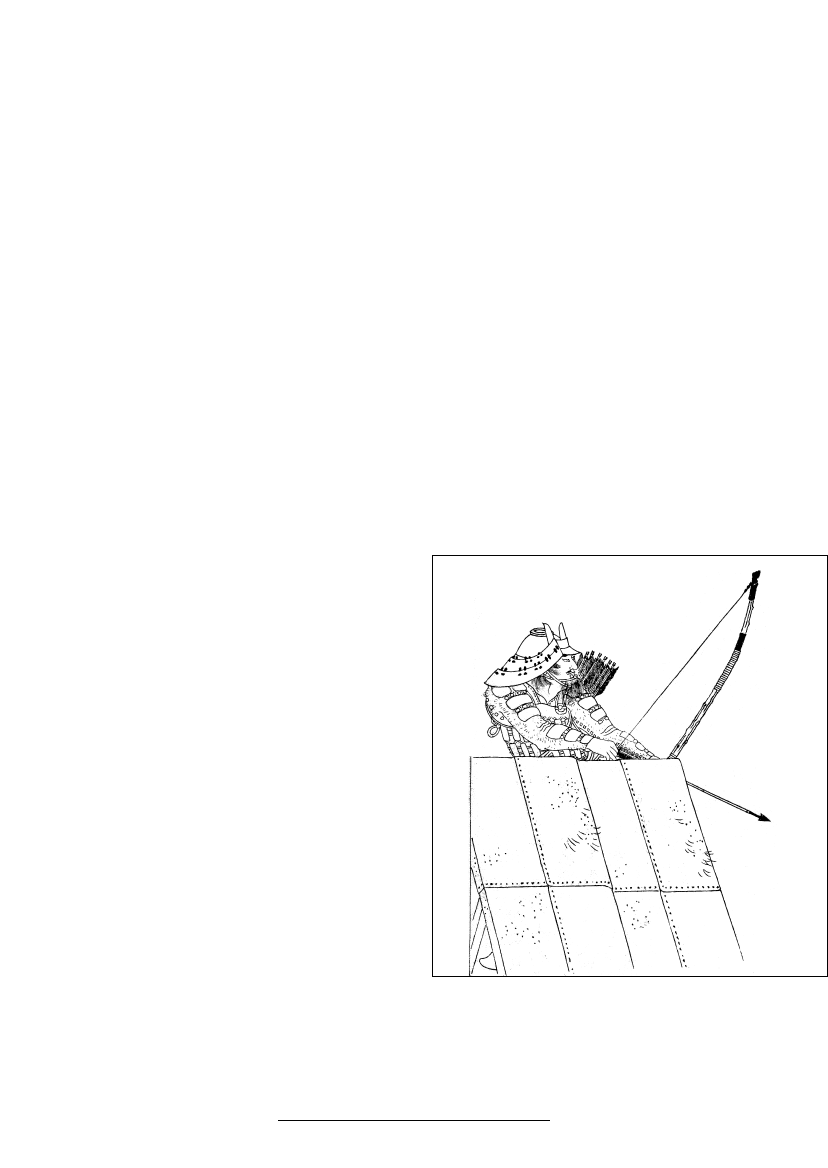

5.11 Warrior shooting arrows from a fixed shield defen-

sive position

(Illustration Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken

kojitsu, mid-19th century)

fields or open plateaus. Large-scale shields were more

easily deployed than brush barriers, which required

significant human labor and large-scale construction,

and shields could be removed to another location

after use. Nonetheless, both shield walls and sakamogi

were vulnerable if confronted with fire, a weapon

favored by early medieval warriors.

Archery/Cavalry Strategy

Since oyoroi armor was heavy enough to slow progress

and freedom of movement, and the bows used in the

early medieval period were weak, Japanese archers

were forced to shoot at close range. With 10 meters

or less between the archer and the target, bowmen

had to carefully identify and target weaknesses in the

opponent’s armor. Further, early medieval samurai

horses had little endurance, especially at high speeds

and while bearing heavy loads, so armies utilized light

cavalry formations in which mounted archers were

surrounded by small groups of infantry circling and

regrouping in a manner that historian Karl F. Friday

has compared to aviators in a dogfight.

Signals and Identification

As armies increased in size, especially during the

Warring States period, opponents often had trouble

identifying each other and commanders could not

recognize important samurai amid the crush of bod-

ies. Signals became an effective means of controlling

troops from a distance during battles, since only

coordinated efforts could be successful. Strategies

included the use of items such as flags, drums, and

conch shells, as well as deployment of fire signals

and messengers. For instance, many samurai and

ashigaru affixed a sashimono, or personal banner, on

the back of their armor. The family crest (mon) of

the army commander was usually painted on the

field of the sashimono, which later developed into the

more visible vertical banner called a nobori carried by

standard bearers into battle. Similarly, recognizing

the potential of messengers, daimyo invested in

preparing elite corps of messengers. A commander

relied upon his messaging system to convey orders

to other generals and ensure timely compliance with

directives. These messengers were specially identi-

fied by cloaks or distinctive sashimono. For example,

Toyotomi Hideyoshi had 29 messengers, all of

whom were fitted with a golden sashimono. Nobu-

naga provided his messengers with a horo, a fabric

bag similar to a cloak attached to the back of the

armor, in either red or black.

During the Warring States period, as the military

became more professionalized and battles were plen-

tiful, specialized signaling and other means of identi-

fying entire companies as well as specific figures were

instituted. To ensure quick identification of opposing

forces at a distance or ready identification of a mili-

tary leader in poor weather, high-ranking figures had

elaborate helmets and other distinguishing charac-

teristics that made them readily recognizable. At the

dawning of this era of many feuding daimyo, the tra-

dition of affixing a sashimono was abandoned, perhaps

because such devices could hinder the progress of an

elite warrior. Regardless, high-ranking samurai had

attendants (standard-bearers) who were charged with

carrying the large vertical flag known as a nobori

identifying the entire company or unit.

Personalized armor or helmet elements func-

tioned like a crest which might be etched into or

painted on European armor to indicate one’s alle-

giance to a particular ruler. However, overall, Japan-

ese use of banners and flags contrasted with

European styles. Apparently, free-flying banners, as

commonly seen in recreations of European battles,

were not favored in Japan. The most typical banner

style of the 15th century and after, the nobori, was a

long, vertical piece of fabric that hung from the arm

of a pole, which could be easily seen from both sides.

Essentially these were larger versions of sashimono

made more visible as well as less personal, a change

that underscores the increasing grandeur of well-

orchestrated combat at the end of the Warring

States period.

Other types of flags and banners served diverse

purposes. Signal flags (as well as fires) could be

employed in directing unit movements. Another

banner used for identification was the uma-jirushi, or

horse insignia, which was worn by the standard-

bearer of a daimyo and used to determine whether a

leading figure had lost his mount.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

180

In peacetime, banners and flags served to distin-

guish rank and status of samurai in service to the

Tokugawa shogunate. Under the reorganization of

the feudal system, samurai rank was equated with

banner size. For example, samurai with an income of

1,300 koku were entitled to bear a small flag, while

those possessing more than 6,000 koku of annual

income could display a large flag. Thus, an

entourage approaching the Tokugawa castle in Edo

could be identified from a distance. Such banners

required three soldiers to serve as bearers, more

than the single figure that had accompanied the

sashimono of high-ranking retainers in the medieval

period. However, due to the dearth of battles, such

flags were displayed primarily during processions of

daimyo to and from the capital, and represented no

hindrance to the typically slow and ceremonious

progress of such entourages.

Battle Formations

Battle formations were predetermined, though once

a battle began there was no requirement or expecta-

tion that the formation would be maintained. Some

formations were specific to interaction among types

of warriors. For example, Japanese cavalry units

included both soldiers on foot and mounted samu-

rai. In this configuration, the figures on foot served

as attendants to the mounted warriors. This had a

strong effect on the maneuverability of the cavalry

W ARRIORS AND W ARFARE

181

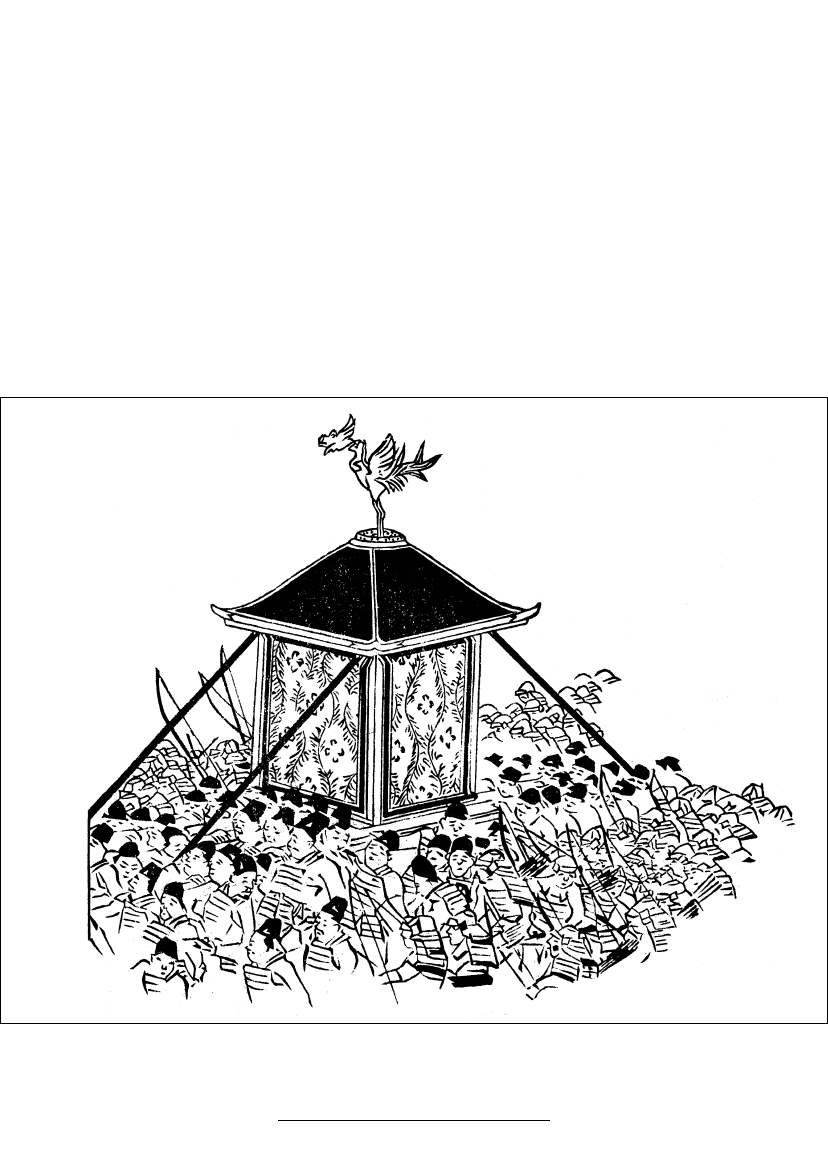

5.12 Warrior procession (Illustration Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken kojitsu, mid-19th century)

unit, as well as the necessary charge distance the unit

required.

There were numerous battle formations utilized

for different strategic moments in a battle. Among

the battle situations for which a specific configura-

tion of troops might be used were formations for the

initial battle charge and for subsequent charges, for-

mations used for surrounding enemy forces, or

when the two armies were of equal strength or when

one army was outnumbered, various defensive for-

mations used to maneuver against the enemy, forma-

tions used under specific terrain conditions,

formations that placed a particular part of one’s

army—for instance, cavalry or foot soldiers—at the

front of the battle, formations for withdrawal, and

formations used for a final stand against an oncom-

ing army.

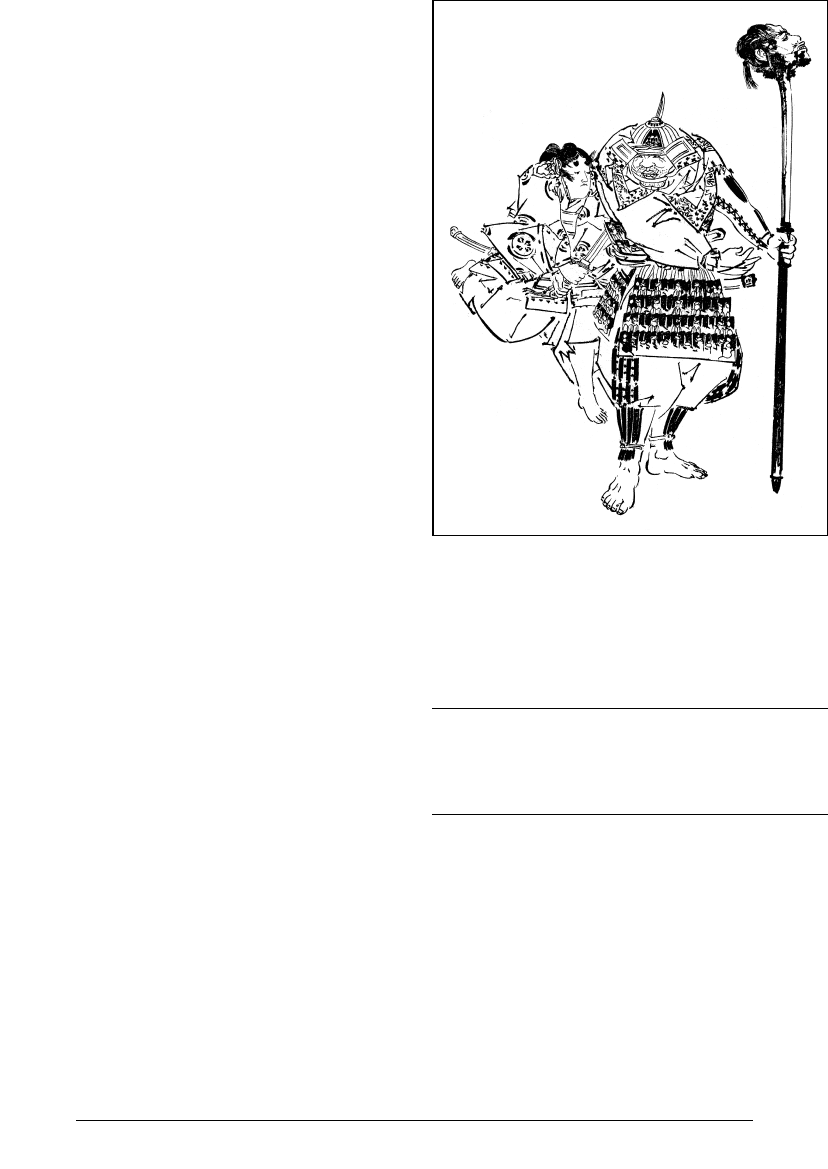

Battle Rituals

The culture of battle in the medieval and early mod-

ern periods was highly ritualized. There were, for

instance, specific ceremonies enacted before going

into battle and specific rituals conducted to celebrate

victory. Before going into battle, it was not uncom-

mon for prayers to be offered to the Shinto gods—

such as to the war deity Hachiman—asking for

divine help in securing victory. Also common was a

ceremonial meal prepared prior to battle in which

sake was drunk and foods with names suggesting vic-

tory were consumed, such as kachi guri, or dried

chestnuts. The term kachi can also mean victory;

hence, the association of “victory chestnuts” with

this food. Finally, the commander would start his

troops marching to battle by uttering a ritual phrase

(“for glory”) while a Shinto priest said additional

prayers for victory. Victory celebrations included rit-

uals such as bathing in a hot spring both as a means

of treating wounds and for purification, the presen-

tation of letters of commendation for bravery or

other heroics, and a “head inspection” in which the

severed heads of the enemy taken during the battle

were presented for review and particular honors

were given to the warrior who had taken the first

head.

WARS AND BATTLES

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF

SIGNIFICANT WARS AND BATTLES

1180–85 Gempei War (also called Taira-

Minamoto War)

Battle of Dannoura

1189 Battle of Hiraizumi

1221 Jokyu Upheaval

1274 First Mongol Invasion (Hakata Bay)

1281 Second Mongol Invasion (Hakata

Bay)

1324 Shochu Upheaval

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

182

5.13 Triumphant warrior with the head of his defeated

enemy

(Illustration Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken kojitsu,

mid-19th century)

W ARRIORS AND W ARFARE

183

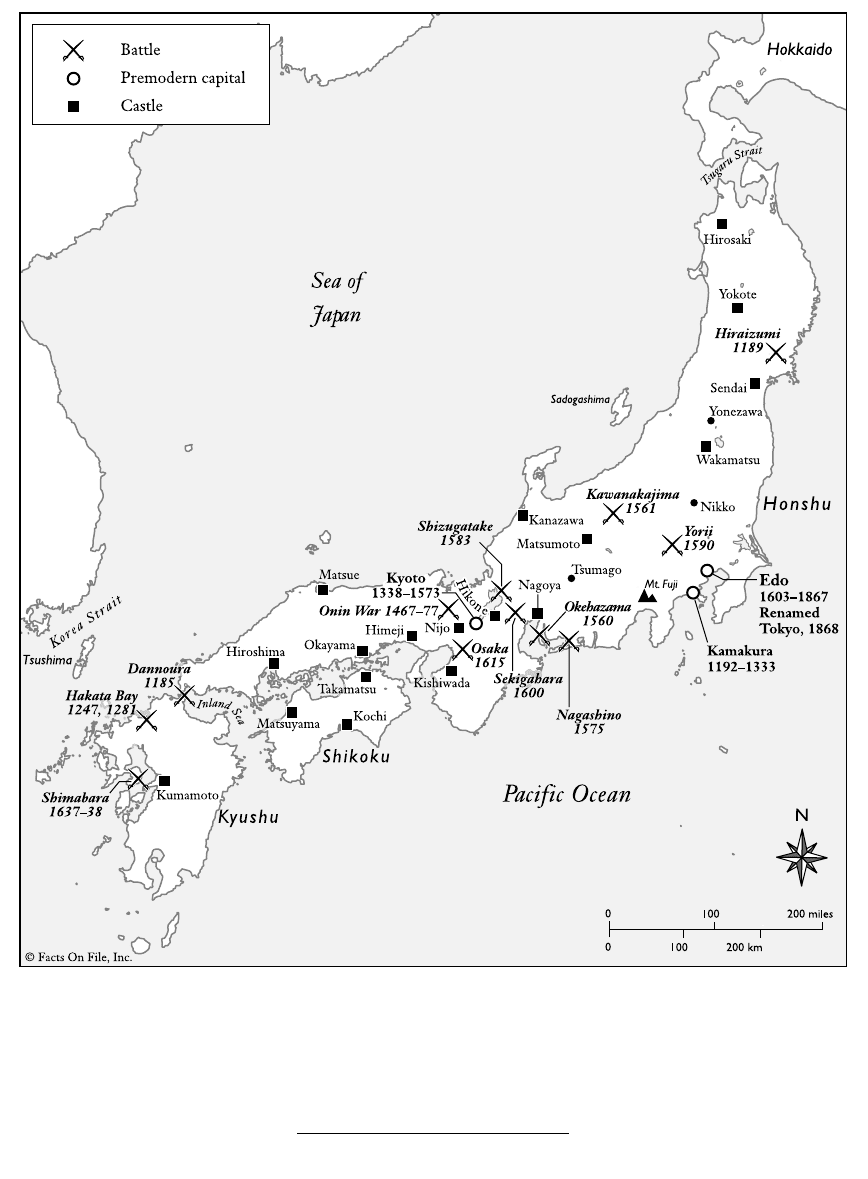

Map 4. Major Battles in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods