Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 2: Since 1500

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

remnants of the Mughal dynasty, which had supported the

mutiny; responsibility for governing the subcontinent was

then turned over to the cro wn.

Like the Sepoy Rebellion, traditional resistance

movements usually met with little success. Peasants armed

with pikes and spears were no match for Western armies

possessing the most terrifying weapons then known to

human society. In a few cases, such as the revolt of the

Mahdi at Khartoum, the natives were able to defeat the

invaders temporarily. But such successes were rare, and

the late nineteenth century witnessed the seemingly in-

exorable march of the Western powers, armed with the

Gatling gun (the first rapid-fire weapon and the precursor

of the modern machine gun), to mastery of the globe.

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

I

MPERIALISM:THE BALANCE SHEET

Few periods of history are as controversial

among scholars and casual observers as

the era of imperialism. To defenders of the

colonial enterprise like the poet Rudyard

Kipling, imperialism was the ‘‘white man’s burden,’’ a

disagreeable but necessary phase in the evolution of

human society, lifting up the toiling races from tradition

to modernity and bringing an end to poverty, famine,

and disease (see the box on p. 518).

Critics took exception to such views, portraying imperialism

as a tragedy of major proportions. The insatiable drive of

the advanced economic powers for access to raw materials

and markets created an exploitative environment that trans-

formed the vast majority of colonial peoples into a perma-

nent underclass, while restricting the benefits of modern

technology to a privileged few. Kipling’s ‘‘white man’s bur-

den’’ was dismissed as a hypocritical gesture to hoodwink

the naive and salve the guilty feelings of those who recog-

nized imperialism for what it was---a savage act of rape.

Defenders of the colonial experiment sometimes con-

cede that there were gross inequities in the colonial system

but point out that there was a positive side to the experi-

ence as well. The expansion of markets and the beginnings

of a modern transportation and communications network, while

bringing few immediate benefits to the colonial peoples, laid the

groundwork for future economic growth. At the same time, the in-

troduction of new ways of looking at human freedom, the relation-

ship between the individual and society, and democratic principles

set the stage for the adoption of such ideas after the restoration of

independence following World War II. Finally, the colonial experi-

ence offered a new approach to the traditional relationship between

men and women. Although colonial rule was by no means uni-

formly beneficial to the position of women in African and Asian so-

cieties, growing awareness of the struggle for equality by women in

the West offered their counterparts in the colonial territories a

weapon to fight against the long-standing barriers of custom and

legal discrimination.

How, then, are we to draw up a final balance sheet on the era

of Western imperialism? Both sides have good points to make, but

perhaps the critics have the best of the argument. Although the co-

lonial authorities sometimes did provide the beginnings of an infra-

structure that could eventually serve as the foundation of an

advanced industrial society, all too often they sought to prevent the

rise of industrial and commercial sectors in their colonies that

might provide competition to producers in the home country. So-

phisticated, age-old societies that could have been left to respond to

the technological revolution in their own way were thus squeezed

dry of precious national resources under the false guise of a ‘‘civiliz-

ing mission.’’ As the sociologist Clifford Geertz remarked in his

book Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in

Indonesia, the tragedy is not that the colonial peoples suffered

through the colonial era but that they suffered for nothing.

Q

Based on the information available to you, do you think

the imperialistic practices of the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries can be justified on moral or political grounds?

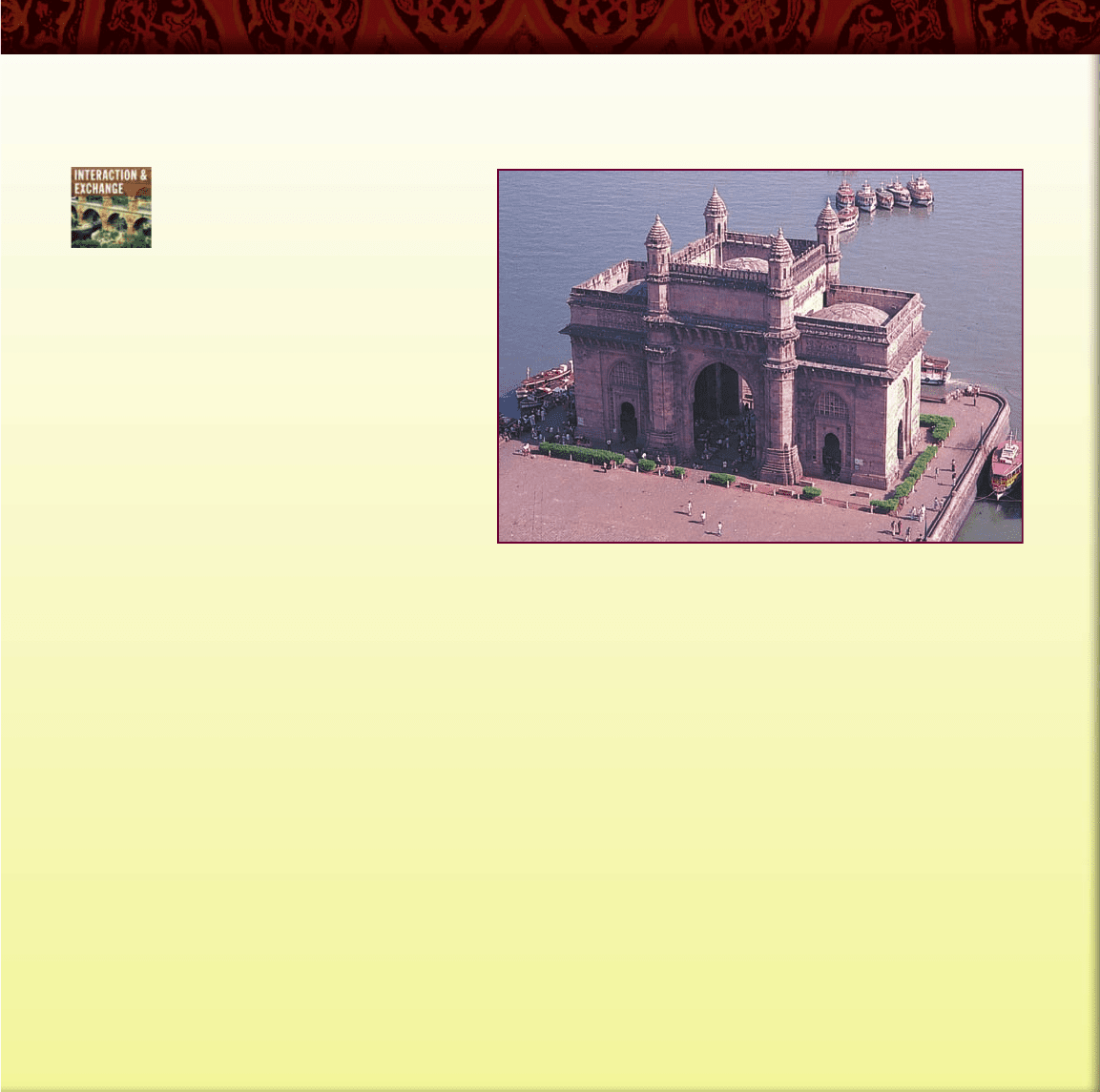

Gateway to India. Built in the Roman imperial style by the British to

commemorate the visit to India of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911, the

Gateway to India was erected at the water’s edge in the harbor of Bombay (now

Mumbai), India’s greatest port city. For thousands of British citizens arriving in

India, the Gateway to India was the first view of their new home and a symbol

of the power and majesty of the British raj.

c

William J. Duiker

536 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

TIMELINE

1800

1820 1840 1860 1880 1900

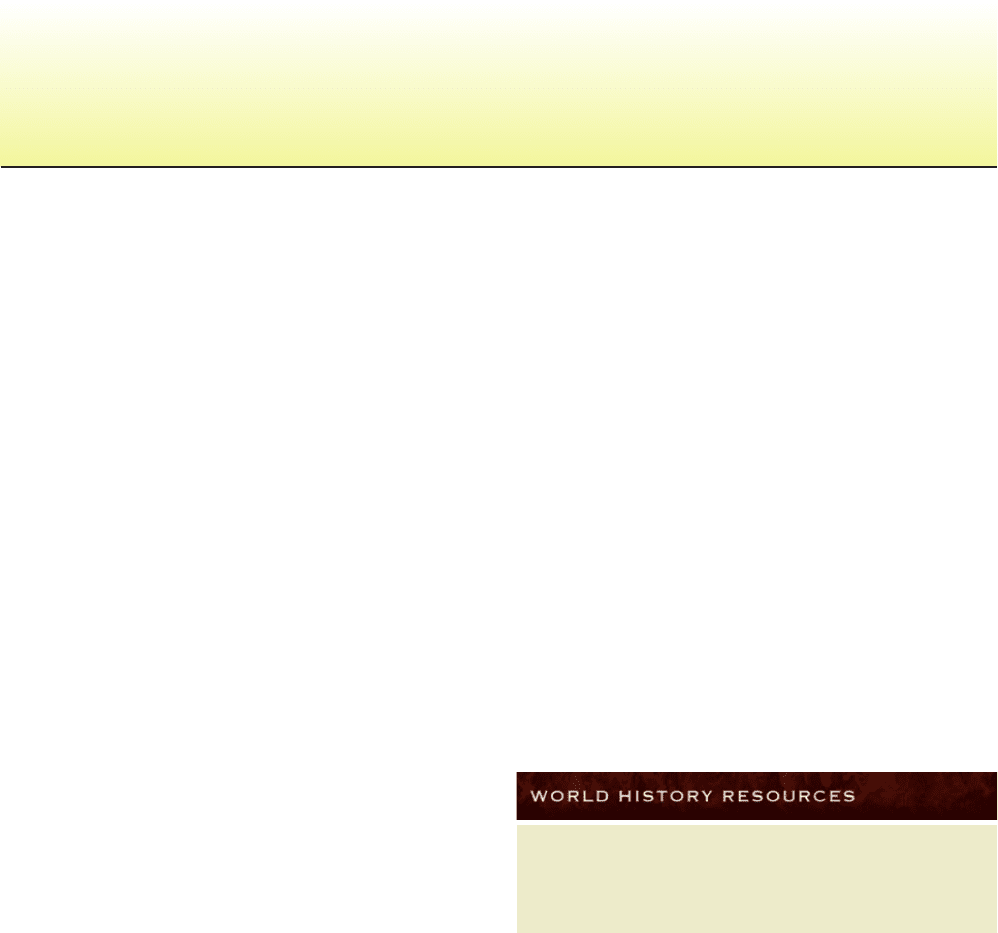

Africa

India

Southeast Asia

Slave trade declared

illegal in Great Britain

Sepoy Rebellion

Stamford Raffles

founds Singapore

First French attack

on Vietnam

Commodore Dewey defeats

Spanish fleet in Manila Bay

French and British agree

to neutralize Thailand

French protectorates

in Indochina

British rail network opened in northern India

French seize Algeria Boer War

Berlin Conference

on Africa

Opening of Suez Canal

CONCLUSION

BY THE FIRST QUARTER of the twentieth century, virtually

all of Africa and a good part of South and Southeast Asia were

under some form of colonial rule. With the advent of the age of

imperialism, a global economy was finally established, and the

domination of Western civilization over those of Africa and Asia

appeared to be complete.

Defenders of colonialism argue that the system was a necessary

if painful stage in the evolution of human societies. Critics,

however, charge that the Western colonial powers were driven by an

insatiable lust for profits (see the comparative essay ‘‘Imperialism:

The Balance Sheet’’ on p. 536). They dismiss the Western civilizing

mission as a fig leaf to cover naked greed and reject the notion that

imperialism played a salutary role in hastening the adjustment

of traditional societies to the demands of industrial civilization.

In the blunt words of two Western critics of imperialism: ‘‘Why is

Africa (or for that matter Latin America and much of Asia)

so poor? ...The answer is very brief: we have made it

poor.’’

10

Between these two irreconcilable views, where does the truth lie?

This chapter has contended that neither extreme position is justified.

Although colonialism did introduce the peoples of Asia and Africa to

new technology and the expanding economic marketplace, it was

unnecessarily brutal in its application and all too often failed to

realize the exalted claims and objectives of its promoters. Existing

economic networks---often potentially valuable as a foundation for

later economic development---were ruthlessly swept aside in the

interests of providing markets for Western manufactured goods.

Potential sources of native industrialization were nipped in the bud to

avoid competition for factories in Amsterdam, London, Pittsburgh,

or Manchester. Training in Western democratic ideals and practices

was ignored out of fear that the recipients might use them as

weapons against the ruling authorities.

The fundamental weakness of colonialism, then, was that it

was ultimately based on the self-interests of the citizens of the

colonial powers. Where those interests collided with the needs of

the colonial peoples, those of the former always triumphed.

CONCLUSION 537

SUGGESTED READING

Imperialism and Colonialism There are a number of good

works on the subject of imperialism and colonialism. For a study

that directly focuses on the question of whether colonialism was

beneficial to subject peoples, see D. K. Fieldhouse, The West and

the Third World: Trade, Colonialism, Dependence, and

Development (Oxford, 1999). Also see W. Baumgart, Imperialism:

The Idea and Reality of British and French Colonial Expansion,

1880--1914 (Oxford, 1982), and D. B. Abernathy, Global

Dominance: European Overseas Empires, 1415--1980 (New Haven,

Conn., 2000). On technology, see D. R. Headrick, The Tentacles

of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism,

1850--1940 (Oxford, 1988). For a defense of the British imperial

mission, see N. Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the

British World Order (New York, 2003).

Imperialist Age in Africa On the imperialist age in Africa,

above all see R. Robinson and J. Gallagher, Africa and the

Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism (London, 1961).

Also see B. Vandervoort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa,

1830--1914 (Bloomington, Ind., 1998), and two works by

T. Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa (New York, 1991) and The

Boer War (London, 1979). On southern Africa, see J. Guy, The

Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom (London, 1979), and D. Nenoon

and B. Nyeko, Southern Africa Since 1800 (London, 1984). Also

informative is R. O. Collins, ed., Historical Problems of Imperial

Africa (Princeton, N.J., 1994).

India For an overview of the British takeover and

administration of India, see S. Wolpert, A New History of India,

8th ed. (New York, 2008). C. A. Bayly, Indian Society and the

Making of the Br itish Empire (Cambridge, 1988), is a scholarly

analysis of the impact of British conquest on the Indian economy.

Also see A. Wild’s elegant East India Company: Trade and

Conquest from 1600 (New York, 2000). For a comparative

approach, see R. Murphey, The Outsiders: The Western Exper ience

in China and India (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1977). In a provocative

work, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford,

2000), D. Cannadine argues that it was class and not race that

motivated British policy in the subcontinent.

Colonial Age in Southeast Asia General studies of the

colonial period in Southeast Asia are rare because most authors

focus on specific areas. For some stimulating essays on a variety of

aspects of the topic, see Continuity and Change in Southeast Asia:

Collected Journal Articles of Harry J. Benda (New Haven, Conn.,

1972). For an overview by several authors, see N. Tarling, ed., The

Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, vol. 3 (Cambridge, 1992).

Women in Africa and Asia For an introduction to the effects

of colonialism on women in Africa and Asia, see S. Hughes and

B. Hughes, Women in World History, vol. 2 (Armonk, N.Y., 1997).

Also consult the classic by E. Boserup, Women’s Role in Economic

Development (London, 1970); J. Taylor, The Social World of

Batavia (Madison, Wis., 1983); and L. Ahmed, Women and

Gender in Islam (New Haven, Conn., 1992).

The ultimate result was to deprive the colonial peoples of the right

to make their own choices about their own destiny.

The continent of Africa and southern Asia were not the only

areas of the world that were buffeted by the winds of Western

expansionism in the late nineteenth century. The nations of eastern

Asia, and those of Latin America and the Middle East as well, were

also affected in significant ways. The consequences of Western

political, economic, and military penetration varied substantially

from one region to another, however, and therefore require separate

treatment. The experience of East Asia will be dealt with in the next

chapter. That of Latin America and the Middle East will be

discussed in Chapter 24.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Critical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

538 CHAPTER 21 THE HIGH TIDE OF IMPERIALISM

539

CHAPTER 22

SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC:

EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Decline of the Manchus

Q

Why did the Qing dynasty decline and ultimately

collapse, and what role did the Western powers play

in this process?

Chinese Society in Transition

Q

What political, economic, and social reforms were

instituted by the Qing dynasty during its final decades,

and why were they not more successful in reversing the

decline of Manchu rule?

A Rich Country and a Strong State:

The Rise of Modern Japan

Q

To what degree was the Meiji Restoration a ‘‘revolution,’’

and to what degree did it succeed in transforming

Japan?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

How did China and Japan each respond to Western

pressures in the nineteenth century, and what

implication did their different responses have for

each nation’s history?

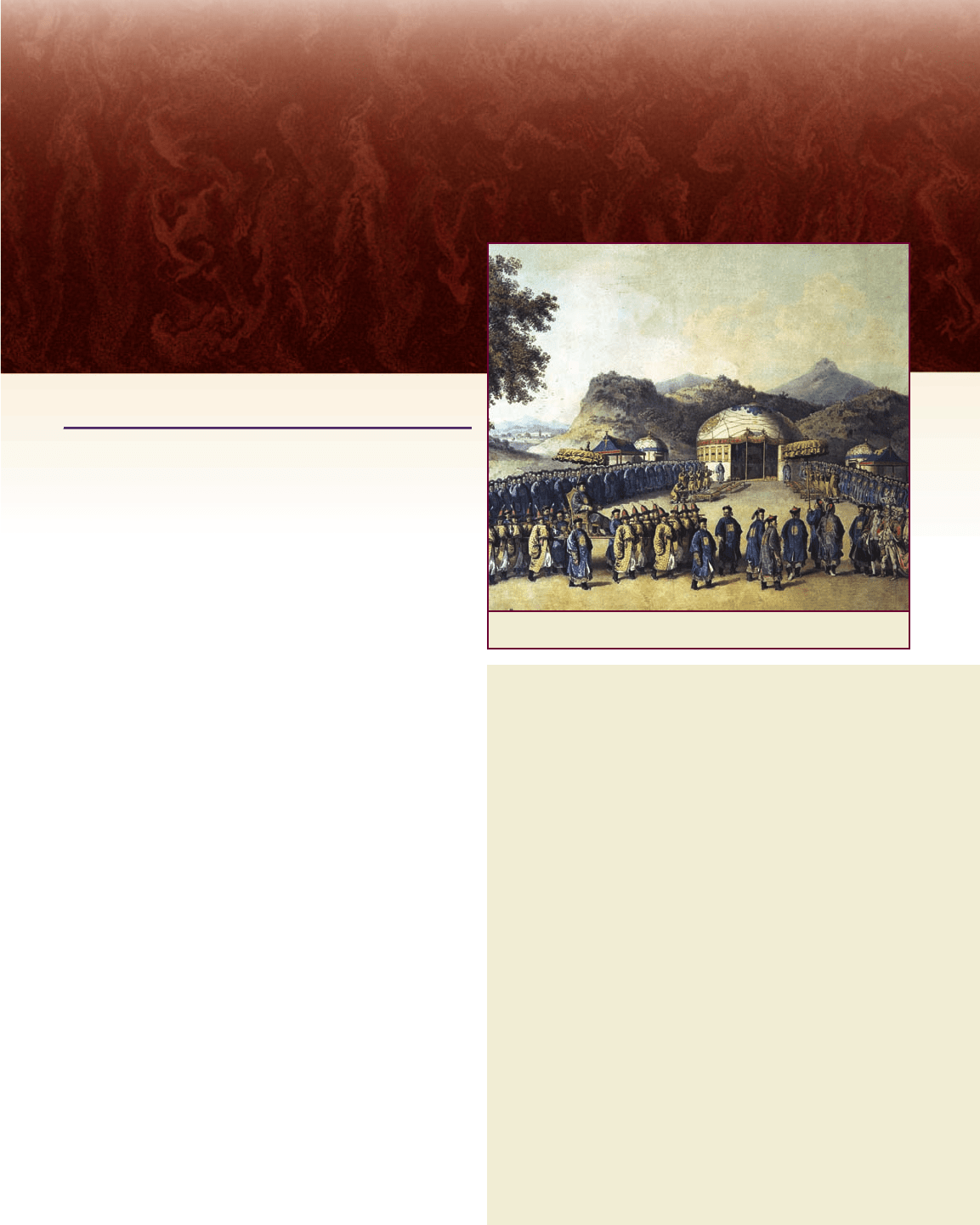

The Macartney mission to China, 1793

The Art Archive/Eileen Tweedy

540

THE BRITISH EMISSARY Lord Macartney had arrived in

Beijing in 1793 with a caravan loaded with six hundred cases of gifts

for the emperor. Flags and banners provided by the Chinese pro-

claimed in Chinese characters that the visitor was an ‘‘ambassador

bearing tribute from the country of England.’’ But the tribute was in

vain, for Macartney’s request for an increase in trade between the two

countries was flatly rejected, and he left Beijing in October with noth-

ing to show for his efforts. Not until half a century later would the

Qing dynasty---at the point of a gun---agree to the British demand for

an expansion of commercial ties.

In fact, the Chinese emperor Qianlong had responded to the

requests of his visitor with polite but poorly disguised condescension.

To Macartney’s proposal that a British ambassador be stationed in the

capital of Beijing, the emperor replied that such a request was ‘‘not in

harmony with the state system of our dynasty and will definitely not be

permitted.’’ As for the British envoy’s suggestion that regular trade rela-

tions be established between the two countries, that proposal was also

rejected. We receive all sorts of precious things, replied the Celestial

Emperor, as gifts from the myriad nations. ‘‘Consequently,’’ he added,

‘‘there is nothing we lack, as your principal envoy and others have

themselves observed. We have never set much store on strange or inge-

nious objects, nor do we need more of your country’s manufactures.’’

The Decline of the Manchus

Q

Focus Question: Why did the Qing dynasty decline

and ultimately collapse, and what role did the Western

powers play in this process?

In 1800, the Qing (Ch’ing) or Manchu dynasty was at the

height of its power. China had experienced a long period

of peace and prosperity under the rule of two great em-

perors, Kangxi and Qianlong. Its borders were secure, and

its culture and intellectual achievements were the envy of

the world. Its rulers, hidden behind the walls of the For-

bidden City in Beijing, had every reason to describe their

patrimony as the ‘‘Central Kingdom.’’ But a little over a

century later, humiliated and harassed by the black ships

and big guns of the Western powers, the Qing dynasty, the

last in a series that had endured for more than two

thousand years, collapsed in the dust (see Map 22.1).

Historians once assume d that the primary reason

for the rapid decline and fall of t he Manchu dyna sty was

the intense pressure applied to a proud but somewhat

complacent traditional society by the modern West.

Now, however, most hist orians believe that internal

changes played a major role in the dynasty’s collapse

andpointoutthatatleastsomeoftheproblemssuf-

fered by the Manchus during the nineteenth century

were self-inf licted.

Both explanations have some validity. Like so many

of its predecessors, after an extended period of growth,

the Qing dynasty began to suffer from the familiar dy-

nastic ills of official corruption, peasant unrest, and in-

competence at court. Such weaknesses were probably

exacerbated by the rapid growth in population. The long

era of peace and stability, the introduction of new crops

from the Americas, and the cultivation of new, fast-

ripening strains of rice enabled the Chinese population

to double between 1550 and 1800. The population

continued to grow, reaching the unprecedented level of

400 million by the end of the nineteenth century. Even

without the irritating presence of the Western powers, the

Manchus were probably destined to repeat the fate of

their imperial predecessors. The ships, guns, and ideas

of the foreigners simply highlighted the growing weakness

of the Manchu dynasty and likely hastened its demise. In

doing so, Western imperialism still exerted an indelible

impact on the history of modern China---but as a con-

tributing, not a causal, factor.

Opium and Rebellion

By 1800, Westerners had been in contact with China for

more than two hundred years, but after an initial period

of flourishing relations, Western traders had been limited

to a small commercial outlet at Canton. This arrangement

was not acceptable to the British, however. Not only did

they chafe at being restricted to a tiny enclave, but the

growing British appetite for Chinese tea created a severe

balance-of-payments problem. After the failure of the

Macartney mission in 1793, another mission, led by Lord

Amherst, arrived in China in 1816. But it too achieved

little except to worsen the already strained relations be-

tween the two countries. The British solution was opium.

A product more addictive than tea, opium was grown in

northeastern India and then shipped to China. Opium

had been grown in southwestern China for several hun-

dred years but had been used primarily for medicinal

purposes. Now, as imports increased, popular demand for

the product in southern China became insatiable despite

an official prohibition on its use. Soon bullion was

flowing out of the Chinese imperial treasury into the

pockets of British merchants.

The Chinese became concerned and tried to negoti-

ate. In 1839, Lin Zexu (Lin Tse-hsu; 1785--1850), a Chi-

nese official appointed by the court to curtail the opium

trade, appealed to Queen Victoria on both moral and

practical grounds and threatened to prohibit the sale of

rhubarb (widely used as a laxative in nineteenth-century

Europe) to Great Britain if she did not respond (see the

box on p. 543). But moral principles, then as now, paled

before the lure of commercial profits, and the British

continued to promote the opium trade, arguing that if the

Chinese did not want the opium, they did not have to buy

it. Lin Zexu attacked on three fronts, imposing penalties

on smokers, arresting dealers, and seizing supplies from

importers as they attempted to smuggle the drug into

China. The last tactic caused his downfall. When he

blockaded the foreign factory area in Canton to force

traders to hand over their remaining chests of opium, the

British government, claiming that it could not permit

British subjects ‘‘to be exposed to insult and injustice,’’

THE DECLINE OF THE MANCHUS 541

Historians have often viewed the failure of the Macartney

mission as a reflection of the disdain of Chinese rulers toward their

counterparts in other countries and their serene confidence in the

superiority of Chinese civilization in a world inhabited by barbar-

ians. If that was the case, Qianlong’s confidence was misplaced, for

as the eighteenth century came to an end, the country faced a grow-

ing challenge not only from the escalating power and ambitions of

the West, but from its own growing internal weakness as well. When

insistent British demands for the right to carry out trade and mis-

sionary activities in China were rejected, Britain resorted to force

and in the Opium War, which broke out in 1839, gave Manchu

troops a sound thrashing. A humiliated China was finally forced to

open its doors.

launched a naval expedition to punish the Manchus and

force the court to open China to foreign trade.

1

The Opium War The Opium War (1839--1842) lasted

three years and demonstrated the superiority of British

firepower and military tactics (including the use of a

shallow-draft steamboat that effectively harassed Chinese

coastal defenses). British warships destroyed Chinese

coastal and river forts and seized the offshore island of

Chusan, not far from the mouth of the Yangtze River.

When a British fleet sailed virtually unopposed up the

Yangtze to Nanjing and cut off the supply of ‘‘tribute

grain’’ from southern to northern China, the Qing finally

agreed to British terms. In the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842,

the Chinese agreed to open five coastal ports to British

trade, limit tariffs on imported British goods, grant ex-

traterritorial rights to British citizens in China, and pay a

substantial indemnity to cover the costs of the war. China

also agreed to cede the island of Hong Kong (dismissed

by a senior British official as a ‘‘barren rock’’) to Great

Britain. Nothing was said in the treaty about the opium

trade, which continued unabated until it was brought

under control through Chinese government efforts in the

early twentieth century.

Although the Opium War has traditionally been

considered the beginning of modern Chinese history, it is

unlikely that many Chinese at the time would have seen it

that way. This was not the first time that a ruling dynasty

had been forced to make concessions to foreigners, and

the opening of five coastal ports to the British hardly

Aral

Sea

Lake

Balkhash

Lake

Baikal

Bay of

Bengal

South

China

Sea

East

China

Sea

Sea of Japan

(East Sea)

Pacific

Ocean

G

a

n

g

e

s

R

.

I

n

d

u

s

R

.

M

e

k

o

n

g

R

.

Y

a

n

g

t

z

e

R

.

Y

e

l

l

o

w

R

.

Urumchi

H

i

m

a

l

a

y

a

M

t

s

.

A

l

t

a

i

M

t

s

.

P

a

m

i

r

M

t

s

.

SAKHALIN

(1853–1875)

(acquired by

Russia,

1858–1860)

KOREA

JAPAN

TAIWAN

(FORMOSA)

RYUKYU

IS.

INDIA

BURMA

THAILAND

VIETNAM

CAMBODIA

PHILIPPINE

ISLANDS

TIBET

MANCHURIA

RUSSIAN EMPIRE

(acquired 1600s–1800s)

XINJIANG

MONGOLIA

KAZAKHSTAN

HINDU

KUSH

LAOS

Nanjing

Hong Kong

(Br. 1842)

Macao

(Port.)

Beijing

Tianjin

Chefoo

Port Arthur

Dairen

Vladivostok

Mukden

Lanzhou

Changsha

Wuhan

Amoy

Taipei

Fuzhou

Gobi Desert

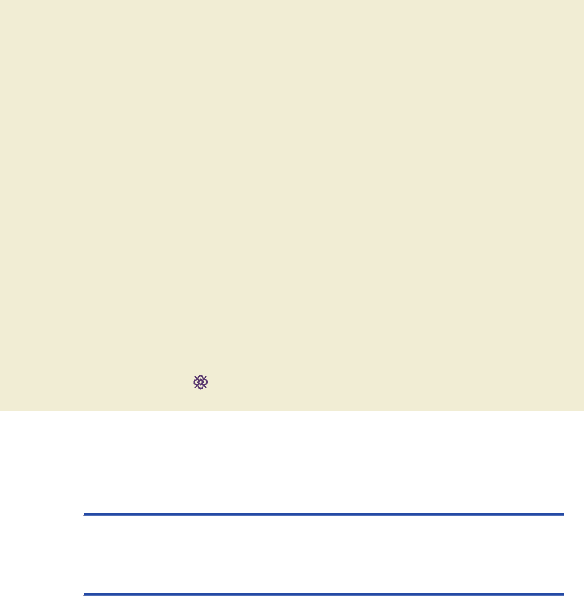

Chinese sphere of influence, 1775

Chinese Empire, 1911

Sometime tributary states to China

0 500 1,000 Miles

0 500 1,000 1,500 Kilometers

MAP 22.1 The Qing Empire. Shown here is the Qing Empire at the height of its power in the

late eighteenth century, together with its shrunken boundaries at the moment of dissolution in 1911.

Q

How do China ’s tributary states on this map differ from those in Map 17.2? W hich of

them fell under the influence of foreign powers during the nineteenth century?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.com /history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

542 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

ALETTER OF ADVICE TO THE QUEEN

Lin Zexu was the Chinese imperial commissioner

in Canton at the time of the Opium War. Prior to

the conflict, he attempted to use reason and the

threat of retaliation to persuade the British to

cease importing opium illegally into southern China. The follow-

ing excerpt is from a letter that he wrote to Queen Victoria.

In it, he appeals to her conscience while showing the conde-

scension that the Chinese traditionally displayed to the rulers

of other countries.

Lin Zexu, Letter to Queen Victoria

The kings of your honorable country by a tradition handed down

from generation to generation have always been noted for their po-

liteness and submissiveness. ... Privately we are delighted with the

way in which the honorable rulers of your country deeply under-

stand the grand principles and are grateful for the Celestial grace. ...

The profit from trade has been enjoyed by them continuously for

two hundred years. This is the source from which your country has

become known for its wealth.

But after a long period of commercial intercourse, there appear

among the crowd of barbarians both good persons and bad, un-

evenly. Consequently there are those who smuggle opium to seduce

the Chinese people and so cause the spread of the poison to all

provinces. ...

The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians. That is

to say, the great profit made by barbarians is all taken from the

rightful share of China. By what right do they then in return use

the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? ...Let us ask,

where is your conscience? I have heard that the smoking of opium

is very strictly forbidden by your country; that is because the harm

caused by opium is clearly understood. Since it is not permitted to

do harm to your own country, then even less should you let it be

passed on to the harm of other countries---how much less to China!

Of all that China exports to foreign countries, there is not a single

thing which is not beneficial to people. ... Is there a single article

from China which has done any harm to foreign countries? Take tea

and rhubarb, for example; the foreign countries cannot get along for

a single day without them. ... On the other hand, ar ticles coming

from the outside to China can only be used as toys. We can take

them or get along without them. Nevertheless our Celestial Court

lets tea, silk, and other goods be shipped without limit and circu-

lated everywhere without begrudging it in the slightest. This is for

no other reason but to share the benefit with the people of the

whole world. ...

May you, O King, check your wicked and sift your vicious

people before they come to China, in order to guarantee the peace

of your nation, to show further the sincerity of your politeness and

submissiveness, and to let the two countries enjoy together the bless-

ings of peace. ... After receiving this dispatch will you immediately

give us a prompt reply regarding the details and circumstances of

your cutting off the opium traffic. Be sure not to put this off.

Q

How did the imperial commissioner seek to persuade

Queen Victoria to prohibit the sale of opium in China?

To what degree are his arguments persuasive?

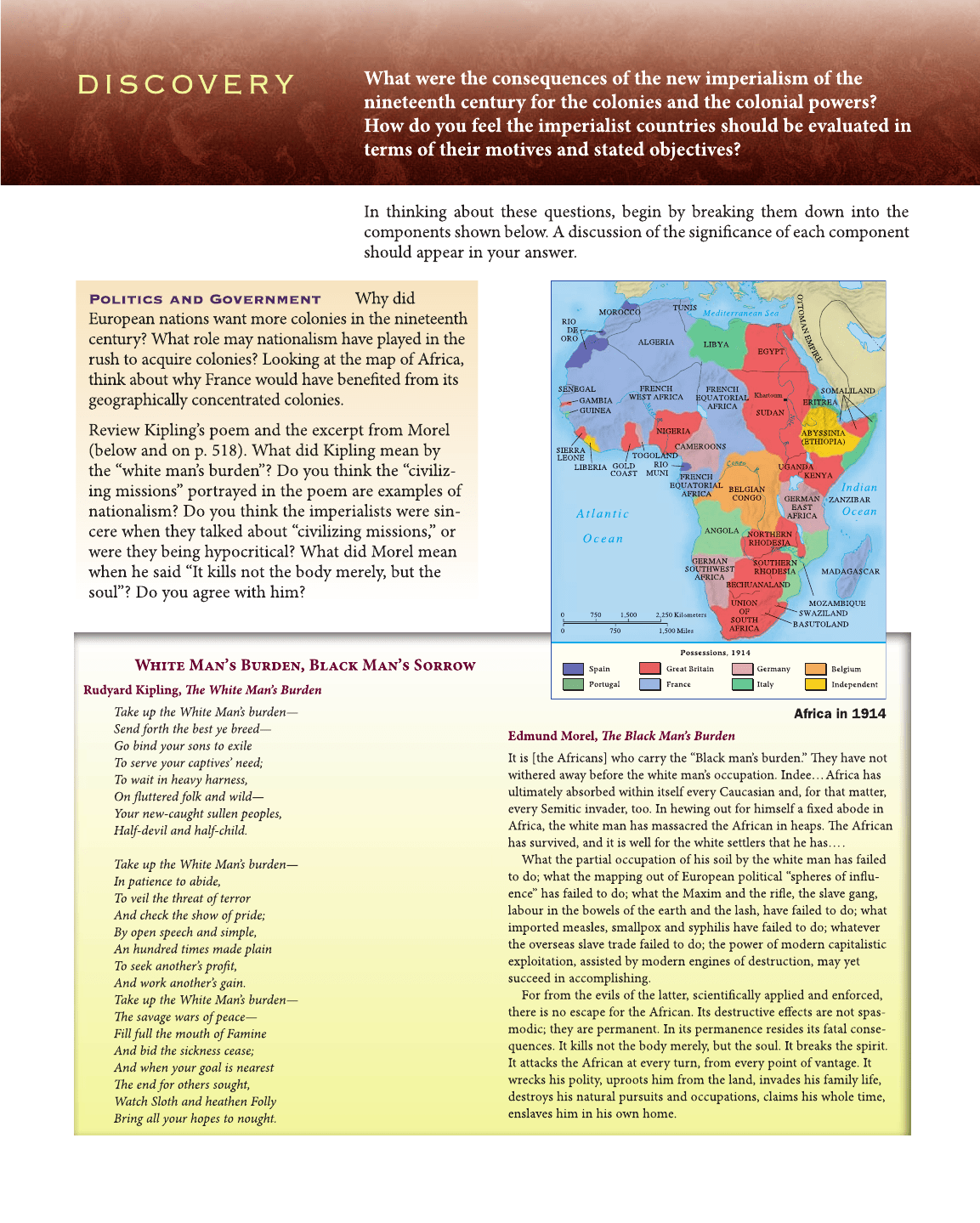

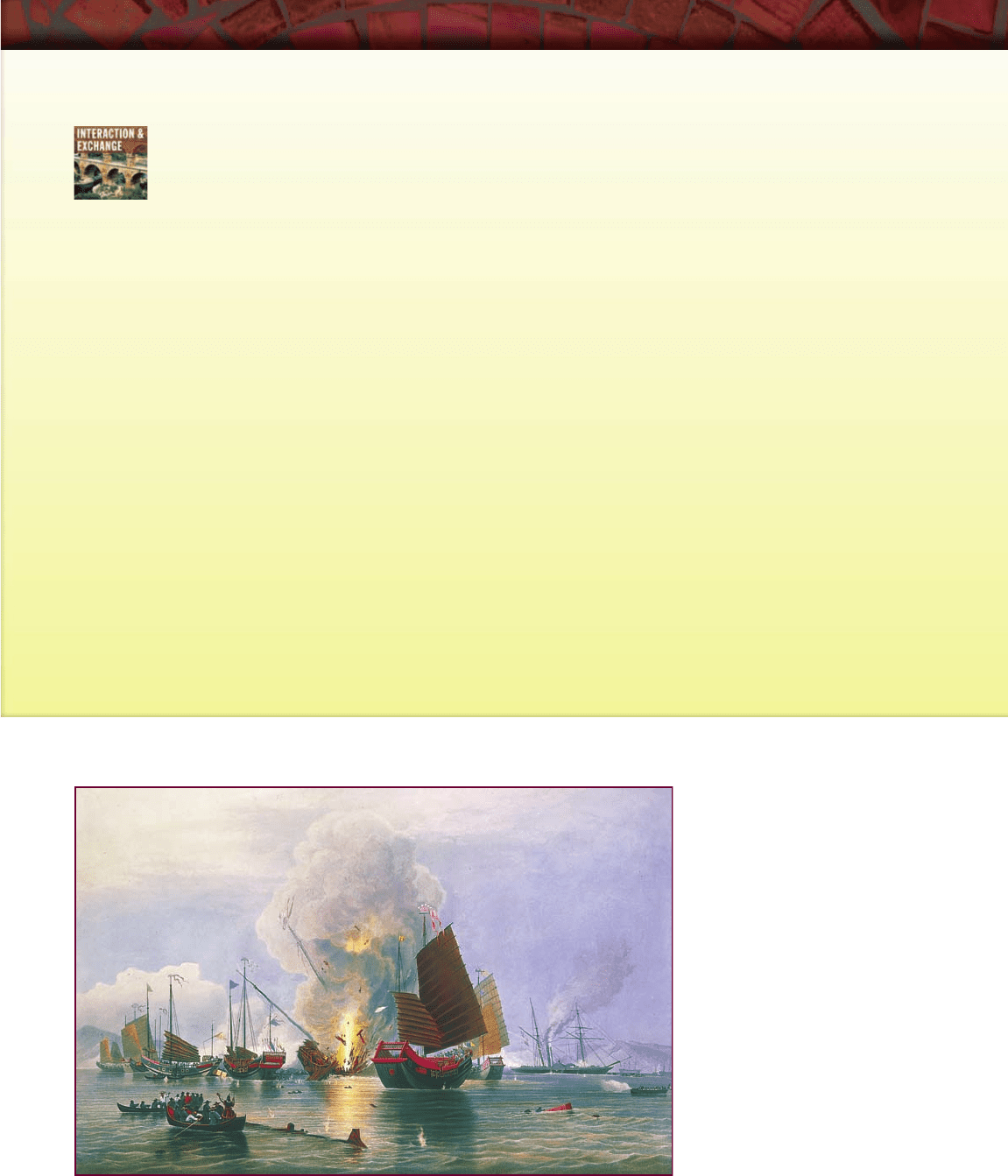

The Opium War. The Opium War,

waged between China and Great Britain

between 1839 and 1842, was China’s first

conflict with a European power. Lacking

modern military technology, the Chinese

suffered a humiliating defeat. In this

painting, heavily armed British steamships

destroy unwieldy Chinese junks along the

Chinese coast. China’s humiliation at sea

was a legacy of its rulers’ lack of interest in

maritime matters since the middle of the

fifteenth century, when Chinese junks were

among the most advanced sailing ships in

the world.

The Art Archives/Eileen Tweedy

THE DECLINE OF THE MANCHUS 543

constituted a serious threat to the

security of the empire. Although a

few concerned Chinese argued

that the court should learn more

about European civilization, oth-

ers contended that China had

nothing to learn from the barbar-

ians and that borrowing foreign

ways would undercut the purity of

Confucian civilization.

For the time being, the Man-

chus attempted to deal with the

problem in the traditional way of

playing the foreigners off against

each other. Concessions granted to

the British were offered to other

Western nations, including the

United States, and soon thriving

foreign concession areas were op-

erating in treaty ports along the

southern Chinese coast from

Canton to Shanghai.

The Taiping Rebellion In the

meantime, the Qing court’s failure

to deal with pressing internal

economic problems led to a major

peasant revolt that shook the

foundations of the empire. On the surface, the Taiping

(T’ai p’ing) Rebellion owed something to the Western

incursion; the leader of the uprising, Hong Xiuquan

(Hung Hsiu-ch’uan), a failed examination candidate, was

a Christian convert who viewed himself as a younger

brother of Jesus and hoped to establish what he referred

to as a ‘‘Heavenly Kingdom of Supreme Peace’’ in China.

But there were many local causes as well. The rapid in-

crease in population forced millions of peasants to eke

out a living as sharecroppers or landless laborers. Official

corruption and incompetence led to the

whipsaw of increased taxes and a de-

cline in government services; even the

Grand Canal was allowed to silt up,

hindering the shipment of grain. In

1853, the rebels seized the old Ming

capital of Nanjing, but that proved to

be the rebellion’s high-water mark.

Plagued by factionalism, the rebellion

gradually lost momentum until it was

finally suppressed in 1864.

One reason for the dynasty’s failure

to deal effectively with the internal

unrest was its continuing difficulties

with the Western imperialists. In 1856,

the British and the French, still smarting from trade re-

strictions and limitations on their missionary activities,

launched a new series of attacks against China and seized

Beijing in 1860. As punishment, British troops destroyed

the imperial summer palace just outside the city. In the

ensuing Treaty of Tianjin (Tientsin), the Qing agreed to

humiliating new concessions: the legalization of the

opium trade, the opening of additional ports to foreign

trade, and the cession of the peninsula of Kowloon (op-

posite the island of Hong Kong) to the British (see

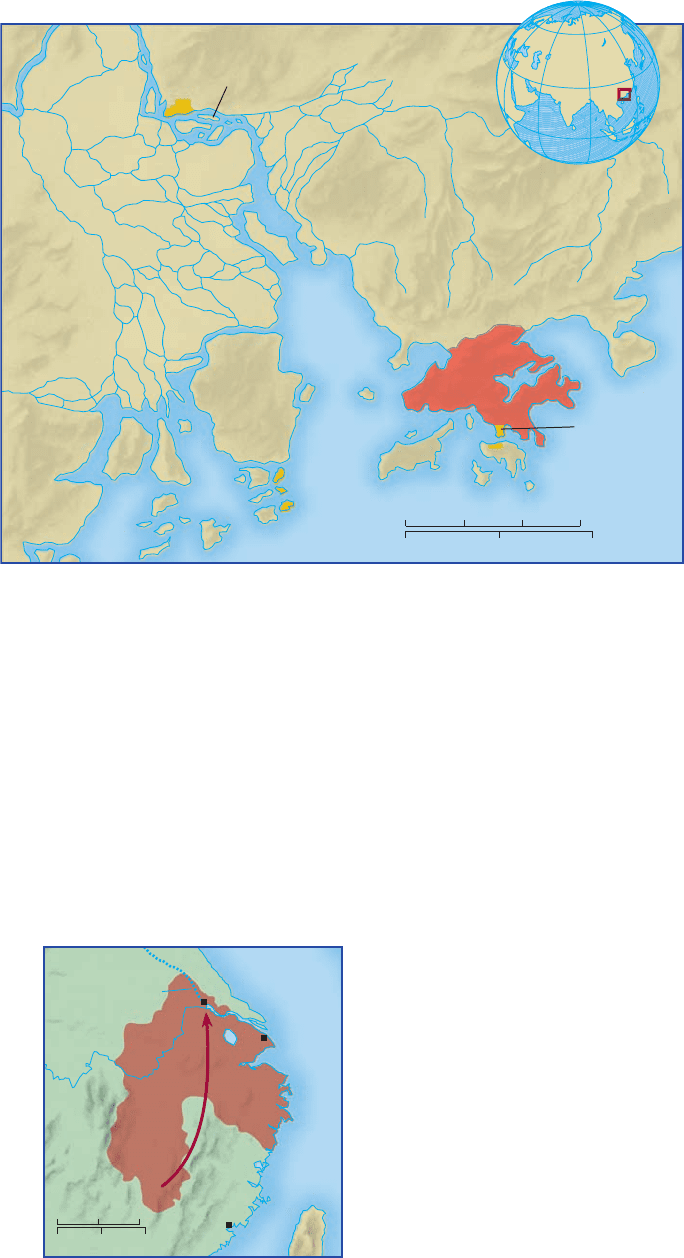

Map 22.2). Additional territories in

the north were ceded to Russia.

Efforts at Refor m

By the late 1870s, the old dynasty was

well on the road to internal disinte-

gration. In fending off the Taiping

Rebellion, the Manchus had been

compelled to rely for support on

armed forces under regional com-

mand. After quelling the revolt, many

of these regional commanders refused

to disband their units and, with the

support of the local gentry, continued

CANTON

MACAO

NEW

TERRITORIES

HONG

KONG

Victoria

Kowloon

Peninsula

Whampoa I.

P

e

a

r

l

R

.

0 20 40 Miles

0 20 40 60 Kilometers

MAP 22.2 Canton and Hong Kong . This map shows the estuary of the Pearl River in

southern China, an important area of early contact between China and Europe.

Q

What was the importance of Canton? What were the N ew Territories, and when

were they annex ed by the British?

CHINA

Taiwan

Nanjing

Xiamen

Shanghai

East

China

Sea

Grand Canal

Y

a

n

g

t

z

e

R

.

200 Miles

300 Kilometers0

0

The Taiping Rebell ion

544 CHAPTER 22 SHADOWS OVER THE PACIFIC: EAST ASIA UNDER CHALLENGE

to collect local taxes for their own use. The dreaded

pattern of imperial breakdown, so familiar in Chinese

history, was beginning to appear once again.

In its weakened state, the court finally began to listen

to the appeals of reform-minded officials, who called for a

new policy of ‘‘self-strengthening,’’ in which Western

technology would be adopted while Confucian principles

and institutions were maintained intact. This policy,

popularly known by its slogan ‘‘East for Essence, West for

Practical Use,’’ remained the guiding standard for Chinese

foreign and domestic policy for nearly a quarter of a

century. Some even called for reforms in education and in

China’s hallowed political institutions. Pointing to the

power and prosperity of Great Britain, the journalist

Wang Tao (Wang T’ao, 1828--1897) remarked, ‘‘The real

strength of England ... lies in the fact that there is a

sympathetic understanding between the governing and

the governed, a close relationship between the ruler and

the people. ... My observation is that the daily domestic

political life of England actually embodies the traditional

ideals of our ancient Golden Age.’’

2

Such democratic ideas

were too radical for most moderate reformers, however.

One of the leading court officials of the day, Zhang

Zhidong (Chang Chih-tung), countered:

The doctrine of people’s rights will bring us not a single

benefit but a hundred evils. Are we going to establish a

parliament? ...Even supposing the confused and clamorous

people are assembled in one house, for every one of them

who is clear-sighted, there will be a hundred others whose

vision is beclouded; they will converse at random and talk

as if in a dream---what use will it be?

3

The Climax of Imperialism For the time being, Zhang

Zhidong’s arguments won the day. During the last quarter

of the century, the Manchus attempted to modernize

their military establishment and build up an industrial

base without disturbing the essential elements of tradi-

tional Chinese civilization. Railroads, weapons arsenals,

and shipyards were built, but the value system remained

essentially unchanged.

In the end, the results spoke for themselves. During

the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the Eu-

ropean penetration of China, both political and military,

intensified. Rapacious imperialists began to bite off the

outer edges of the Qing Empire. The Gobi Desert north of

the Great Wall, Central Asia, and Tibet, all inhabited by

non-Chinese peoples and never fully assimilated into the

Chinese Empire, were gradually lost. In the north and

northwest, the main beneficiary was Russia, which took

advantage of the dynasty’s weakness to force the cession

of territories north of the Amur River in Siberia. In Tibet,

competition between Russia and Great Britain prevented

either power from seizing the territory outright but at the

same time enabled Tibetan authorities to revive local

autonomy never recognized by the Chinese. In the south,

British and French advances in mainland Southeast Asia

removed Burma and Vietnam from their traditional

vassal relationship to the Manchu court. Even more

ominous were the foreign spheres of influence in the

Chinese heartland, where local commanders were willing

to sell exclusive commercial, railroad-building, or mining

privileges.

The breakup of the Manchu dynasty accelerated at

the end of the nineteenth century. In 1894, the Qing went

to war with Japan over Japanese incursions into the

Korean peninsula, which threatened China’s long-held

suzerainty over the area (see ‘‘Joining the Imperialist

Club’’ later in this chapter). To the surprise of many

observers, the Chinese were roundly defeated, confirming

to some critics the devastating failure of the policy of self-

strengthening by halfway measures. The disintegration of

China accelerated in 1897, when Germany, a new entry in

the race for spoils in East Asia, used the pretext of the

murder of two German missionaries by Chinese rioters to

demand the cession of territories in the Shandong

(Shantung) peninsula. The imperial court approved the

demand, setting off a scramble for territory by other in-

terested powers (see Map 22.3). Russia now demanded

the Liaodong peninsula with its ice-free port at Port

Arthur, and Great Britain weighed in with a request for a

coaling station in northern China.

The government responded to the challenge with yet

another effort at reform. In the spring of 1898, an out-

spoken advocate of change, the progressive Confucian

scholar Kang Youwei (K’ang Yu-wei), won the support of

the young Guangxu (Kuang Hsu) emperor for a com-

prehensive reform program patterned after recent mea-

sures in Japan. Without change, Kang argued, China

would perish. During the next several weeks, the emperor

issued edicts calling for major political, administrative,

and educational reforms. Not surprisingly, Kang’s pro-

posals were opposed by many conservatives, who saw

little advantage and much risk in copying the West. More

important, the new program was opposed by the em-

peror’s aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi (Tz’u Hsi), the

real power at court (see the comparative illustration on

p. 547). Cixi had begun her political career as a concubine

to an earlier emperor. After his death, she became a

dominant force at court and in 1878 placed her infant

nephew, the future Guangxu emperor, on the throne. For

two decades, she ruled in his name as regent. With the aid

of conservatives in the army, she arrested and executed

several of the reformers and had the emperor incarcerated

in the palace. With Cixi’s palace coup, the so-called One

Hundred Days of reform came to an end.

THE DECLINE OF THE MANCHUS 545