Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

per farm, accounting for some 80 percent of total

sown area in agriculture. After World War II a pro-

gram of amalgamation and also of conversion to

state farms was implemented along with a contin-

uing program of agroindustrial integration. As a

result, the number of collective farms declined to

approximately 27,000 by 1988, with an average

size of 22,000 acres, together accounting for 44

percent of sown area. By the end of the 1980s, the

differences between kolkhozes and sovkhozes were

minimal.

During the transition era of the 1990s, change

in Russian agriculture has been very slow. Collec-

tive farms have for the most part been converted

to a corporate structure, but operational changes

have been few, and a significant land market re-

mains to be achieved.

See also: AGRICULTURE; COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICUL-

TURE; PEASANT ECONOMY; SOVKHOZ

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, R. W. (1980). The Soviet Collective Farm, 1929-

1930. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stuart, R. C. (1972). The Collective Farm in Soviet Agricul-

ture. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITY

Collective or mutual responsibility (krugovaia

poruka), often reinforced through legal guarantees

or surety bonds.

It is first documented in the medieval period in

an expanded version of the Russkaya Pravda that

mandated that certain communities would be col-

lectively responsible for apprehending murderers or

paying fines to the prince. In the Muscovite period

collective responsibility was frequently invoked to

make communities collectively responsible for the

actions and financial obligations of their members.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, state of-

ficials shifted much of the responsibility for appre-

hending criminals and preempting misdeeds to

groups that could monitor and discipline their

members. Surety in the form of financial and legal

accountability was frequently demanded by the

state from groups to insure that their individual

members would not shirk legal obligations or re-

sponsibilities such as appearing in court, perform-

ing services for the state, or meeting the terms of

contracts. Although the state moved away from

the pervasive application of the principle of collec-

tive responsibility in the eighteenth century, it was

still used in certain situations such as military con-

scription and collection of delinquent taxes. Even

after the Great Reforms, local police officials re-

tained the right to hold large peasant communes

collectively responsible for major tax arrears as a

measure of last resort. Although theoretically state

officials could inventory and sell individual hold-

ings to cover communal arrears, in practice this oc-

curred infrequently. In Soviet legal procedures

collectives could be called upon to monitor and

vouch for their members, and individuals accused

of committing minor legal infractions could be

handed over to a collective for corrective measures

as an alternative to incarceration.

See also: GREAT REFORMS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dewey, Horace W., and Kleimola, Ann M. (1970). “Sure-

tyship and Collective Responsibility in Pre-Petrine

Russia.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 18:

337–354.

B

RIAN

B

OECK

COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE

The introduction of the collective farm (kolkhoz)

into the Soviet countryside began in the late 1920s

and was substantially completed by the mid-

1930s. The collectivization of Soviet agriculture,

along with the introduction of state ownership (na-

tionalization) and national economic planning (re-

placing markets as a mechanism of resource

allocation), formed the dominant framework of the

Soviet economic system, a set of institutions and

related policies that remained in place until the col-

lapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917,

Lenin attempted to introduce change in the Soviet

agricultural sector, and especially to exert state

control, through methods such as the extraction of

grain from the rural economy by force (the pro-

drazverstka). This was the first attempt under Soviet

rule to change both the institutional arrangements

governing interaction between the agrarian and in-

dustrial sectors (the market) and the terms of trade

between the state and the rural economy. The im-

pact of these arrangements resulted in a significant

COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE

283

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

decline in agricultural output during the period of

war communism.

Following the collapse of war communism, the

peasant economy predominated during the New

Economic Policy (NEP). The relationship between

the rural economy and the urban industrial econ-

omy was characterized by alliance (smytchka), al-

though the issue of the rural economy and its role

in socialist industrialization remained controver-

sial. Events such as the Scissors Crisis brought these

issues to the fore. In addition, the potential contri-

bution of agriculture to the process of economic

development was a major issue in the great indus-

trialization debate.

In 1929 Josef Stalin initiated the process of col-

lectivization, arguing that a “grain crisis” (peasant

withholding of grain) could effectively limit the

pace of Soviet industrialization. Collectivization

was intended to introduce socialist organizational

arrangements into the countryside, and to change

fundamentally the nature of the relationship be-

tween the rural and urban (industrial) sectors of

the Soviet economy. Markets were to be eliminated,

and state control was to prevail.

The organizational arrangements in the coun-

tryside were fundamentally changed, the relations

between the state and the rural economy were al-

tered, and the socialist ideology served as the frame-

work for the decision to collectivize. The process

and outcome of collectivization remain controver-

sial to the present time.

Why has collectivization been so controversial?

First, the process of collectivization was forcible and

violent, resulting in substantial destruction of phys-

ical capital (e.g., animal herds) and the reduction of

peasant morale, as peasants resisted the state–driven

creation of collective farms. Second, the kolkhoz as

an organization incorporated socialist elements into

the rural economy. It was also viewed as a mecha-

nism through which state and party power could

be used to change the terms of trade in favor of the

city, to eliminate markets, and, specifically, to ex-

tract grain from the countryside on terms favorable

to the state. The collective farm was, in theory, a

cooperative form of organization through which

the state could extract grain, leaving a residual for

peasant consumption. The mechanism of payment

for labor, the labor day (trudoden), facilitated this

process. Third, peasant resistance to the creation of

the collective farms was cast largely within an ide-

ological framework. Thus resistance to collectiviza-

tion, in whatever form, was blamed largely upon

the wealthy peasants (kulaks). Fourth, the institu-

tions and policies resulting from the collectivization

process, even with significant modifications over

time, have been blamed for the poor record of agri-

cultural performance in the Soviet Union. In addi-

tion to the costs associated with the initial means of

implementation, the collective farms lacked suffi-

cient means of finance and were unable to provide

appropriate incentives to stimulate the necessary

growth of agricultural productivity.

Thus collectivization replaced markets with

state controls and, in so doing, used a process and

instituted a set of organizational arrangements ul-

timately deemed to be detrimental to the long–term

growth of the agricultural economy in the Soviet

Union.

See also: AGRICULTURE; COLLECTIVE FARM; ECONOMIC

GROWTH, SOVIET; PEASANT ECONOMY; SOVKHOZ

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, R. W. (1980). The Socialist Offensive: The Collec-

tivisation of Soviet Agriculture, 1929-1930. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lewin, Moshe. (1968). Russian Peasants and Soviet Power:

A Study of Collectivization. London: Allen & Unwin.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

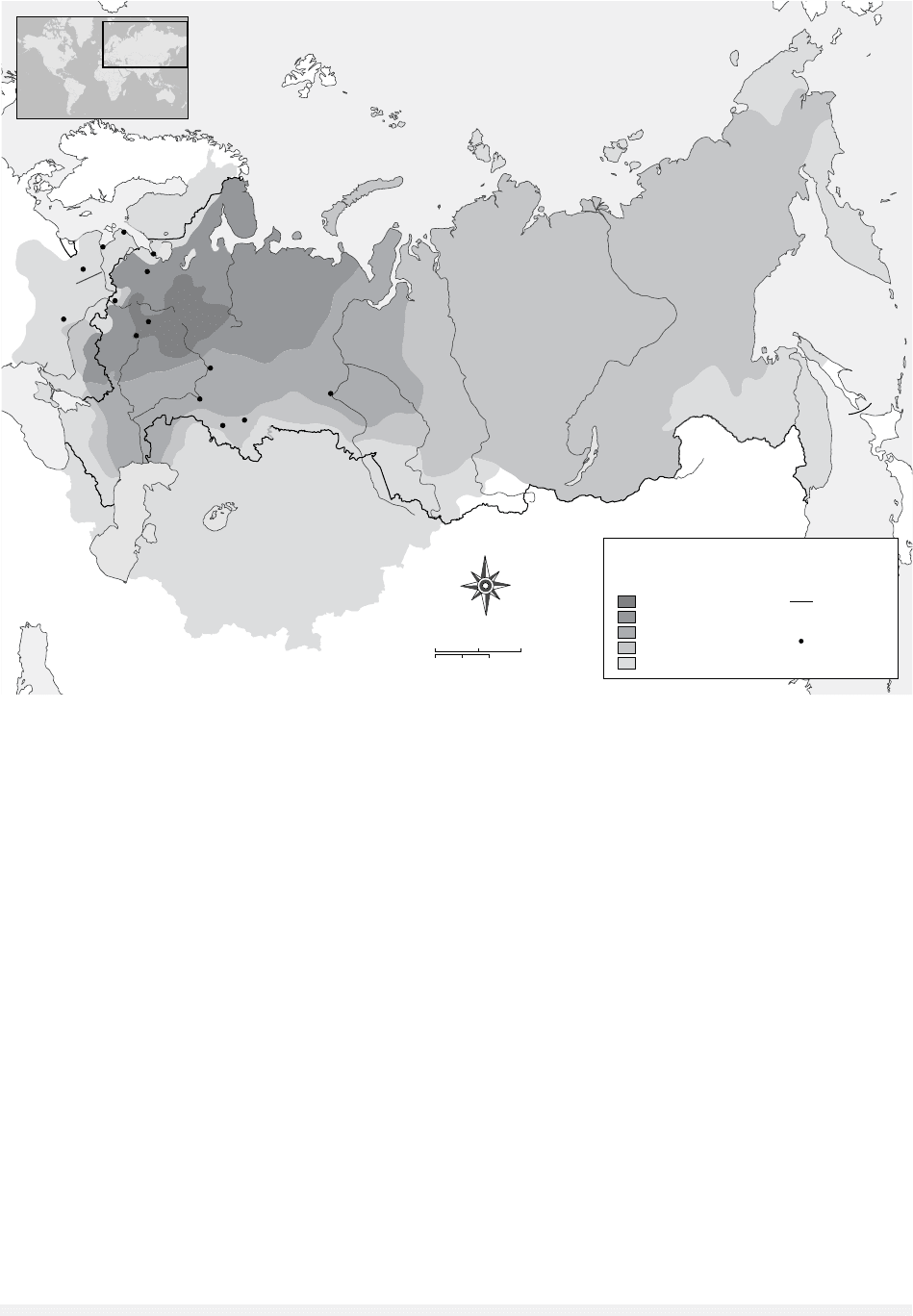

COLONIAL EXPANSION

In 1300 Moscow was the capital of a very small,

undistinguished principality whose destiny was al-

most certainly beyond anyone’s imaginings at the

time: by 1991, it would control more than one-

sixth of the earth’s landed surface. This expansion

was achieved by many means, ranging from mar-

ital alliances and purchase to military conquest and

signed treaties.

Moscow was already in control of a multira-

cial, multiethnic region in 1300. The primordial in-

habitants were Finnic. Much later Balts moved in,

and then around 1100 Slavs migrated to the re-

gion, some from the south (from Kievan Rus), per-

haps the majority from the west, the area of

Bohemia. In 1328 the Russian Orthodox Church

established its headquarters in Moscow, giving sta-

bility to the Moscow principality at crucial junc-

tures and helping legitimize its annexation of other,

primarily Eastern Slavic, principalities. Much of the

Muscovite expansion was nearly bloodless, as elites

COLONIAL EXPANSION

284

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in other principalities chose to join the elite in Mos-

cow over liquidation or marginalization in small

principalities. After 1450 Moscow’s rivals became

more formidable, especially the Republic of Nov-

gorod in the northwest, with its vast lands in the

Russian North (annexed as the result of military

campaigns in 1471 and 1478); the eastern entre-

pot of the Hansa League, at the time perhaps the

major fur supplier to much of Eurasia; and Lithua-

nia, the largest state in Europe in the mid-fifteenth

century. Moscow unleashed its army against

Lithuania and by 1514 had annexed much of its

territory (sometimes known as “West Russia”).

In the mid-sixteenth century Muscovy pursued

colonial expansion full force. In 1552 the Tatar

Khanate of Kazan was annexed, and in 1556, after

a dash down the Volga, the Tatar Khanate of As-

trakhan was conquered. Although Muscovy con-

trolled numerous regions from 1300 onward, the

annexations of the 1550s converted Muscovy into

a truly multinational empire. Both moves were

made for security concerns, only marginally (at

best) for economic reasons.

The conquests of Kazan and Astrakhan made

it possible for the Russians to move farther east,

first into the Urals, then into Siberia. There the

Muscovite expansion began to take on hues re-

sembling Western European colonial expansion

into the New World and Asia. A pivotal figure was

Ermak Timofeyev syn (i.e., son of the commoner

Timofei; had Ermak’s father been of noble origin,

then his patronymic would have been Timofee-

vich), a cossack ataman who at the end of the

1570s or the beginning of the 1580s (the precise

date is unknown) campaigned into Siberia and ini-

tiated the destruction of the Tatar Siberian Khanate.

Once the Siberian Khanate was annexed, the path

was open through Siberia to the Pacific. The Rus-

sians garrisoned strategic points and began to col-

lect tribute (primarily in furs, especially sables)

from the Siberian natives. Colonial expansion in

many parts of the world was not profitable, be-

cause administrative costs ate up whatever gains

from trade there may have been. In Siberia, how-

ever, the opposite has been true for more than four

centuries. The conquest, pacification, and continu-

ing administrative costs were low there, while the

remittances to Moscow and St. Petersburg in the

form of furs, gold and other precious metals, dia-

monds, timber, and, more recently, oil and gas were

all profitable. If one includes the Urals, developed

between the reign of Peter the Great and 1800, the

trans-Volga push was very profitable for Russia.

The colonists who settled Eurasia between the

Urals and the Pacific were certainly among the

most motley ever assembled. Leading the pack were

cossacks and other adventurers. They were fol-

lowed by fur traders and perhaps trappers. Gov-

ernment officials and garrison troops were next.

They were followed by peasants fleeing serfdom,

then by exiles from the center. Even as late as the

last years of the Soviet Union, permanent residents

of Siberia volunteered aloud their disgust over the

fact that Moscow used their land as a dumping

ground for criminal and political exiles. In the

eighteenth century landlords claimed huge tracts in

Siberia and moved all of their peasants from Old

Russia to the new lands. Probably the last wave

were Soviet professionals who responded to

quadruple wages to settle in mineral-rich but cli-

matically unfriendly regions of Siberia.

Moscow’s push south of the Oka into the

steppe was at least initially a defensive measure.

The Crimean Tatars sacked Moscow in 1571 and

its suburbs in 1591, and they regularly “harvested”

tens of thousands of Slavs into captivity for sale

into the world slave trade out of Kefe across the

Black Sea. To put a stop to these continuous depre-

dations, the Muscovites paid annual tributes to the

Crimeans that were never sufficient, mounted pa-

trols along the southern frontier, and began the

process of walling it off from the steppe to keep

the nomads from penetrating Eastern Slavdom. A

series of fortified lines were built in the steppe, un-

til the Crimean Khanate was surrounded and then

finally annexed in 1783. What began as a security

measure turned into a great economic boon for

Russia. Most of the area annexed was chernozem

soil, prairie soil a yard thick that proved to be the

richest soil in Europe. The western part of this area

had been Ukraine, which was annexed in 1654. The

eastern part of the steppe was uninhabited because

of continuous Tatar depredations. Once it was se-

cure, it was settled primarily by Russian farmers

hoping to improve on their yields from the pitiful

podzol soils north of the Oka. This colonization

gave the Russians access to the sixty-thousand-

square-kilometer Donbass, one of late Russia’s and

the USSR’s major fuel and metallurgical regions.

The homeland of the Great Russians, the Volga-

Oka mesopotamia, is almost totally lacking in use-

ful minerals and suitable soil and weather for

productive agriculture—all of which were supplied

by the colonization of Ukraine and Siberia.

One of Russia’s good fortunes was that gener-

ally it was able to pick its colonization-annexation

COLONIAL EXPANSION

285

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

targets one at a time. Peter the Great in 1703 an-

nexed the Neva delta, which became the site of the

future capital, St. Petersburg, and gave Russia di-

rect access to Baltic and Atlantic seaports of tremen-

dous value during the next three centuries. The next

target to the west was Poland, which was divided

into three partitions (among Russia, Austria, and

Prussia). The first partition, in 1772, involved pri-

marily lands that once had been East Slavic, but the

second (1793) and third (1795) engorged West

Slavic territories, including the capital of Poland it-

self, Warsaw. This strategic move netted Russia

more intimate access to the rest of Europe, but oth-

erwise gave the Russians nothing but trouble: the

enduring hatred of the Poles, rebellions by Poles

against Russian hegemony, and dissent by Russians

who opposed the annexation of Poland.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Russian Empire

moved against the Caucasus. This move led to the

horror of the Caucasian War, which dragged on

from 1817 to 1864. Control over the Caucasus had

been contested for centuries among the Persians,

the Byzantines, the Ottomans, and the Russians.

There, Christianity and Islam met head to head. The

Islamic Chechens were among the first peoples at-

tacked in 1817, an event that reverberates to this

day. The Armenian and Georgian Christians looked

to the Russians to save them from Islamic conquest.

The Russians ultimately won, but at tremendous

cost and for little real gain.

In 1864 Russia turned its attention to Central

Asia. Between then and 1895 it defeated and an-

nexed to the Russian Empire the weak khanates of

Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khiva. Central Asia was

inhabited by primarily Turkic nomads. Silk was the

main product manufactured there that the Russians

wanted, as well as access via commercial trans-

portation to Balkh, Afghanistan, and India further

south. In Soviet times Uzbekistan was foolishly

converted into the cotton basket of the USSR at the

cost of drying up the Syr Daria and Amu Daria

rivers and the Aral Sea, leaching the soil, and con-

verting the region into a toxic dust bowl.

Russia was successful in its colonial empire

building efforts because of the weakness and dis-

organization of its opponents. Areas such as

Poland, the Caucasus, and Central Asia benefited

Russia little, whereas St. Petersburg, Siberia, and

left-bank Ukraine were profit centers for Russia and

for the USSR.

See also: DEMOGRAPHY; EMPIRE, USSR AS; MILITARY, IM-

PERIAL ERA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, Brian. (1983). “The Role of the Town Governors

in the Defense and Military Colonization of Muscovy’s

Southern Frontier: The Case of Kozlov, 1635–1638.”

2 vols. Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

Davies, Norman. (1982). God’s Playground: A History of

Poland. 2 vols. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (2002). “Migration in Early Modern Rus-

sia, 1480s–1780s.” In Coerced and Free Migration:

Global Perspectives, ed. David Eltis. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

Khodarkovsky, Michael. (2002). Russia’s Steppe Frontier:

The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1550–1800. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

COLONIALISM

Colonialism is a type of imperial domination of the

non-Russian peoples who inhabited the southern

and eastern borderlands of the Russian Empire and

who subsequently fell under the control of the So-

viet Union. It refers specifically to policies to spread

Western civilization (a “civilizing mission”) among

peoples in those territories, and to integrate them

into the imperial state and economy. It extends as

well to the colonization by Russian and Ukrainian

peasant settlers of lands inhabited by pastoral no-

madic tribes.

COLONIZATION

The Russian Empire’s southern and eastern

borderlands became its colonial territories. Russian

expansion onto the plains of Eurasia had by the

middle of the eighteenth century brought within

the boundaries of the empire all the lands south to

the Caucasus Mountains and to the deserts of

Turkestan, and east to the Pacific Ocean. Much of

the area consisted of vast plains (the “steppe”) once

dominated by confederations of nomadic tribes,

who became the subjects of imperial rule and the

empire’s first colonized peoples. The grasslands

where they grazed their flocks along the lower

Volga River and in southern Russia (the Ukraine)

attracted peasants from European Russia seeking

new farmland.

The imperial government encouraged this

southward movement of the Russian population

(most of whom were serfs owned by noble land-

lords). Occasionally nomadic tribes fought to re-

COLONIALISM

286

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tain their lands. Prolonged resistance came first

from the Bashkirs, Turkic peoples whose tribes oc-

cupied lands east of the Volga and along the Ural

Mountains. During the eighteenth century many

clans joined in raids on the intruders and battled

against Russian troops. They joined in the massive

Pugachev uprising of 1772 to 1774 alongside Cos-

sacks and rebellious Russians. But in the end Rus-

sian armed forces invariably defeated the rebels.

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth

century, Russia’s borders of the empire shifted fur-

ther southeastward into Eurasian lands, bringing

an increasingly diverse population into the empire.

Peoples in these borderlands spoke many different

languages, mostly of Turkic origin; practiced a

wide variety of religions, with the Islamic faith the

most widespread; and followed their own time-

honored customs and social practices. Russia was

becoming a multiethnic, multireligious empire.

THE IMPERIAL CIVILIZING MISSION

In the reign of Empress Catherine II (r. 1762–1796),

the empire’s leadership began to experiment with

new approaches to govern these peoples. These poli-

cies drew upon Enlightenment concepts of govern-

ment that redefined the object of colonial conquests.

They became the basis of Russian colonialism. Pre-

viously, the Russian state had extended to the

princes and nobles of newly conquered eastern ter-

ritories the chance to collaborate in imperial rule.

It had required their conversion to Orthodox Chris-

tianity, and had periodically encouraged Orthodox

missionaries to conduct campaigns of mass con-

version, if necessary by force. Before Catherine II’s

time, the state had made no concerted effort to al-

ter the social, economic, and cultural practices of

the peoples on its southern and eastern borderlands.

This authoritarian method of borderland rule de-

manded only obedience from the native popula-

tions.

COLONIALISM

287

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

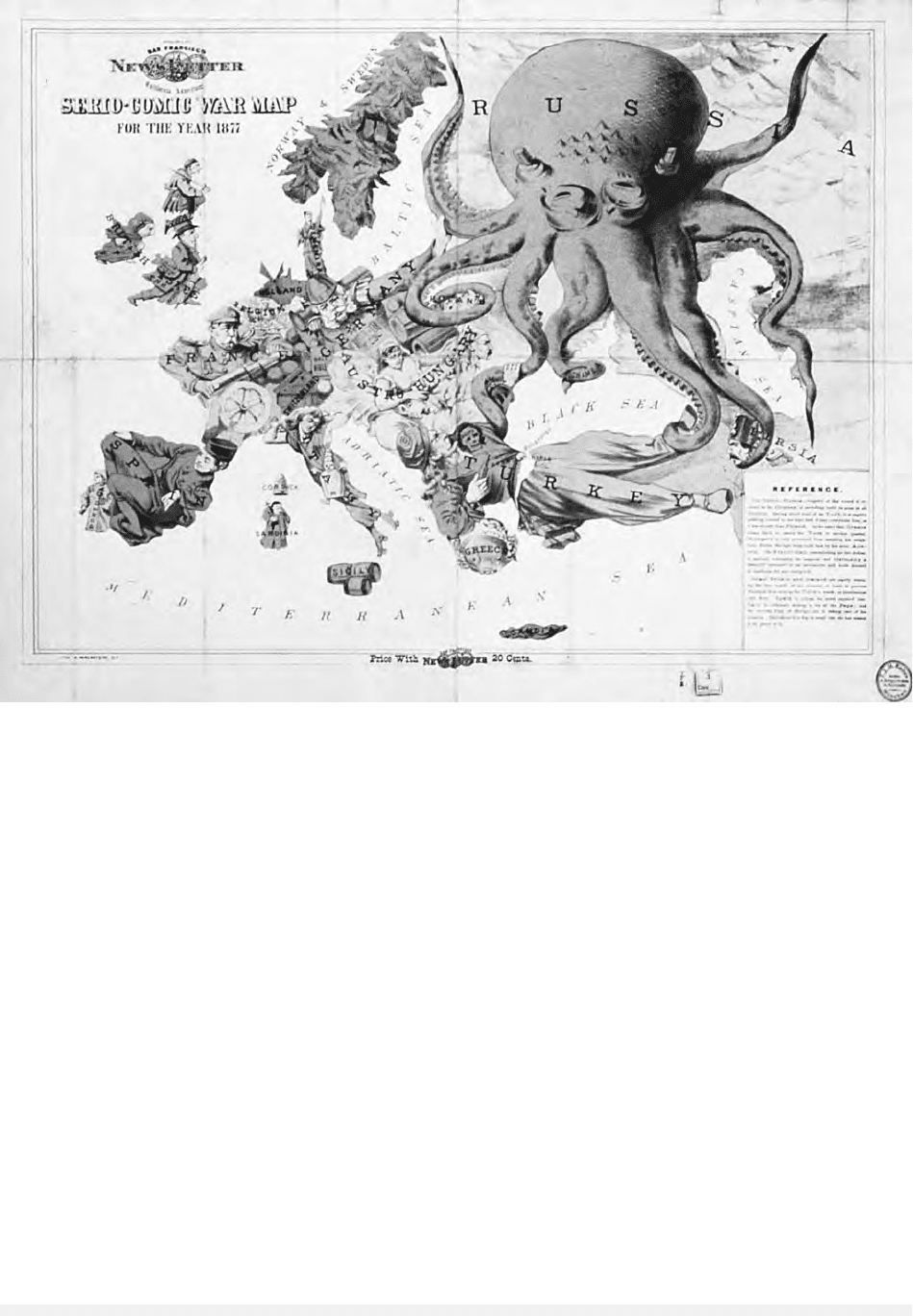

A greedy octopus represents Russia’s expanding influence in 1877. © CORBIS

In the late eighteenth century, some educated

Russians began to argue that their empire, which

they believed a civilized Western land, had the duty

to spread civilization, as they understood it, to its

backward peoples. They had two principal objec-

tives. By spreading Russian culture, legal practices,

and opportunities for economic enrichment, the

empire could hope to recruit a progressive group

from these peoples who would become willing col-

laborators in Russian domination. Equally impor-

tant was their belief that Russia’s own historical

development made the spread of its newly acquired

Western culture among “savage” peoples a moral

obligation.

Catherine II herself traveled among the empire’s

eastern peoples at the beginning of her reign. Im-

pressed by what she described as the “differences of

peoples, customs, and even ideas” in Asian land,

she looked for new ways to win the loyalty of the

population. Encouragement of trade, education,

and religious toleration appeared to her desirable

and useful tools to strengthen the bonds between

these colonial peoples and their imperial rulers.

These goals suggested practical guidelines by which

she and her advisers could build their empire on

modern political foundations. These also confirmed

in their eyes the legitimacy of their imperial dom-

ination of backward peoples.

Catherine II shared the Enlightenment convic-

tion that reason, not religious faith, lay at the core

of enlightened government. She did not abandon

the policy of maintaining Orthodox Christianity as

the state religion of the empire, but ended forced

conversion of Muslim peoples to Christianity. In

1773, she formally accorded religious toleration to

Islam. Her successors on the imperial throne main-

tained this fundamental right, which proved a

valuable means of maintaining peaceful relations

with the empire’s growing Muslim population.

They encouraged the conversion to Christianity of

peoples holding to animist beliefs, for they believed

that their duty was to favor the spread of Chris-

tianity. They also promoted the commercial ex-

ploitation of colonial resources and the increased

sale of Russian manufactured goods in their colo-

nial territories. The Western colonialists’ slogan of

“Commerce and Christianity” described one impor-

tant aspect to Russia’s civilizing mission. Self-in-

terest as well as the belief in spreading the benefits

of Western civilization provided the ideological ba-

sis for Russian colonialism. This new policy never

fully supplanted the old practices of authoritarian

rule and discrimination against non-Russians,

which had strong defenders among army officers

on the borderlands. But it, too, enjoyed powerful

backing in the highest government circles. In the

nineteenth century, their vision of an imperial civ-

ilizing mission brought Russia into the ranks of

great Western empires.

COMMERCE AND CHRISTIANITY

IN COLONIAL ALASKA

Alaska was the first area where Russian colonial-

ism guided imperial rule. In the late eighteenth cen-

tury Russian trappers had appeared there, having

crossed the Pacific Ocean along the Aleutian Islands

from Siberia in their hunt for fur-bearing sea

mammals. The sea otter, whose fur was so highly

prized that it was called “soft gold,” was their cho-

sen prey. They forced native peoples skilled at the

dangerous craft of hunting at sea (mainly Aleut-

ian tribesmen) to trap the animals, whose range

extended from the Aleutians along the Alaskan

coast and down to California. In 1800, the Russian

government created a special colonial administra-

tion, the Russian-American Company, to take

charge of “the Russian colonies in America.” Its

main tasks were to expand the commercially prof-

itable fur-gathering activities, and to spread Or-

thodox Christianity and Russian culture among the

subject peoples of this vast territory.

“Commerce and Christianity” defined the Rus-

sian Empire’s objectives there. It operated in a man-

ner somewhat similar to that of the British

Hudson’s Bay Company, also established in colo-

nial North America. And like other overseas colonies

of European empires, the Russians exploited Alaska’s

valuable resources (killing off almost all the sea

otters), in the process confronting periodic revolts

from their subject peoples. Faced with these diffi-

culties, the Russian government finally abandoned

its distant colony, too expensive and too distant to

retain. In 1867, it sold the entire territory to the

United States.

COLONIAL TURKESTAN AND

IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP

In seeking to create a unified, modern state, the

Russian Empire moved toward establishing a com-

mon citizenship for the peoples in its multiethnic,

multireligious borderlands in the late nineteenth

century. It began this effort in 1860s and 1870s,

at the time when it freed its peasant serf popula-

tion from conditions of virtual slavery to its no-

bility. Reformers in the government conceived of

an empire founded on a sort of imperial citizen-

COLONIALISM

288

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ship, extended to former serfs and to native peo-

ples.

That was the period of the empire’s last ma-

jor colonial expansion, when its military forces

conquered a large part of Central Asia. The settled

and nomadic populations of Turkestan (as the area

was then called) spoke Turkic languages and were

faithful Muslims who looked to the Ottoman Em-

pire, not Russia, for cultural and religious leader-

ship. The Russian colonial administration was

deeply divided on the proper treatment of their un-

willing new subjects. Some preferred to rely on the

old policies of authoritarian rule, restrictions of the

Muslim religion, and the encouragement of Rus-

sian colonization. Others took their inspiration

from Catherine II’s colonialist policies. The latter

argued for progressive colonial policies including

religious toleration of Islam, respect for the ethnic

customs and moral practices of Turkestan’s peo-

ples, and the development of new crops (especially

cotton) and commercial trade with Russia. They

hoped that, as the powerful Minister of Finance

Sergei Witte argued in 1900, full equality of rights

with other subjects, freedom in the conduct of their

religious needs, and non-intervention in their pri-

vate lives, would ensure the unification of the

Russian state.

This progressive colonialist program was no-

table by according (in theory) “equality of rights”

to these imperial subjects. Colonial officials of this

persuasion believed that they could extend, within

their autocratic state, a sort of imperial citizenship

to all the colonial peoples. They withheld, however,

the full implementation of this reform until these

peoples were “ready,” that is, proved themselves

loyal, patriotic subjects of the emperor-tsar. Op-

position to their policy came from influential civil-

ian leaders who judged that the state’s need to

support Russian peasants colonizing Turkestan ter-

ritories had to come first. Their reckless decision led

to the seizure from nomadic tribes of vast regions

of Turkestan given to the peasant pioneers. Colo-

nization meant violating the right of these subjects

to the use of their land, which led directly to the

Turkestan uprising of 1916. Coming before the

1917 revolution, this rebellion revealed that the

empire’s colonialist policies had failed to unify its

peoples.

ORIENTALISM IN THE

CAUCASUS REGION

To the end of the empire’s existence, colonialism

rested on the assumption of Russian cultural su-

periority and often expressed itself in disdain for

colonial peoples. Yet not all of these subject groups

were treated with equal disregard. In the territories

of the Caucasus Mountains (between the Black and

Caspian Seas), imperial rule won the support of

some peoples, but faced repeated revolts from oth-

ers. Resistance came especially from Muslim moun-

tain tribes, who bitterly opposed domination by

this Christian state. They sustained a half-century

war until their defeat in the 1860s, when many

were forced into exile or emigrated willingly to

the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of the region

produced an abundance of heroic tales of exotic ad-

ventures pitting valorous Russians against bar-

baric, cruel, and courageous enemies. These tales

created enduring images of “oriental” peoples,

sometimes admired for their “noble savagery” but

usually disparaged for their alleged moral and cul-

tural decadence.

Russian colonialism had a powerful impact on

the population there. The Christian peoples (Geor-

gians and Armenians) of the region found partic-

ular benefits from the empire’s economic and

cultural policies. Armenians created profitable com-

mercial enterprises in the growing towns and cities

of the Caucasus region, and were joined by large

numbers of Armenian migrants from surrounding

Muslim states. Some Georgians used the empire’s

cultural window on modern Western culture to

create their own national literature and history.

These quickly became tools in the Georgians’ na-

tionalist oppositional movement. In the Muslim

lands along the Caspian Sea where Azeri Turks

lived, investors from Russia and Europe developed

the rich oil deposits into one of the first major

sources of petroleum for the European economy, a

source of immense profit to them. The port of Baku

became a boomtown, where unskilled Azeri labor-

ers worked in the dangerous oil fields. They formed

a colonial proletariat living among Russian officials

and capitalists, and Armenian merchants and

traders. The new colonial cities such as Baku were

deeply divided both socially and ethnically, and be-

came places in the early twentieth century of riots

and bloodshed provoked by the hostility among

these peoples. Nationalist opposition to empire and

ethnic conflict among its peoples were both prod-

ucts of Russian colonialism.

COLONIALISM IN THE SOVIET UNION

The fall of the empire in 1917 ended Russian

colonialism as a publicly defended ideal and pol-

icy. The triumph of the communist revolutionary

COLONIALISM

289

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

movement in most of the lands once a part of the

empire put in place a new political order, called the

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The commu-

nist leaders of the new Soviet state preached the

Marxist-Leninist program for human progress.

They persecuted all religious movements, and de-

nounced imperialism and colonialism, in Russia as

elsewhere in the Western world. Their promise was

liberation of all colonial peoples. But they did not

permit their own peoples, previously in the em-

pire’s colonial lands, to escape their domination.

Their idea of “colonial liberation” consisted of or-

ganizing these peoples into discreet ethno-territo-

rial units by drawing territorial borders for every

distinct people. The biggest of these received their

own national republics. Each of these nations of

the Soviet Union had its own political leaders and

its own language and culture, but the “union” to

which they belonged remained under the domina-

tion of the Communist Party, itself controlled from

party headquarters in the Kremlin in Moscow.

The empire’s eastern peoples experienced a new,

communist civilizing mission, which proclaimed the

greatest good for backward peoples to be working-

class liberation, national culture, and rapid economic

development under state control. Colonization reap-

peared as well when, in the 1950s and 1960s, mil-

lions of settlers from European areas moved into

Siberia and regions of Central Asia to cultivate, in

enormous state-run farms, most of the remaining

lands of the nomadic peoples. Colonialism within the

lands of the former Russian Empire did not disap-

pear until the Soviet Union in its turn collapsed in

1991.

See also: CATHERINE II; CAUCASUS; CHRISTIANITY, COLO-

NIAL EXPANSION; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF THE;

COLONIALISM

290

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A

R

C

T

I

C

O

C

E

A

N

Sea of

Okhotsk

Sea of

Japan

Bering

Sea

Barents

Sea

Kara

Sea

Laptev

Sea

Chukchi

Sea

East

Siberian

Sea

B

l

a

c

k

S

e

a

C

a

s

p

i

a

n

S

e

a

Crimea

L

e

n

a

R

.

I

r

t

y

s

h

R

.

O

b

R

.

V

o

l

g

a

R

.

N

.

D

v

i

n

a

R

.

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

R

.

D

o

n

R

.

Y

e

n

i

s

e

y

R

.

Western

Dvina R.

A

m

u

r

R

.

Ukraine

Kiev

Ufa

Orenburg

Vilnius

Tallinn

Riga

Smolensk

Kazan’

Samara

Tobol’sk

Moscow

Moscow

Tula

Moscow

Tula

St. Petersburg

Novgorod

C

A

UC

AS

US

S

I

B

E

R

I

A

U

R

A

L

M

O

U

N

T

A

I

N

S

N

0 250 500 mi.

0 250 500 km

Russian Imperial

Expansion, 1552–1800

Present-day

boundary

of Russia

City

Moscow, 1462

Expansion 1462–1533

Expansion 1533–1584

Expansion 1584–1689

Expansion 1689–1914

By 1914, the Russian Empire controlled more than one-sixth of the Earth’s landed surface. XNR P

RODUCTIONS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

OF THE

G

ALE

G

ROUP

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brower, Daniel. (2003). Turkestan and the Fate of the Rus-

sian Empire. London: Routledge/Curzon.

Brower, Daniel, and Lazzerini, Edward, eds. (1997).

Russia’s Orient: Imperial Borderlands and Peoples,

1700–1917. Bloomington: University of Indiana

Press.

Jersild, Austin. (2002). Orientalism and Empire: The North

Caucasus Mountain Peoples and the Georgian Frontier,

1845–1917. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University

Press.

Khodarkovsky, Michael. (2002). Russia’s Steppe Frontier:

The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800. Bloom-

ington: University of Indiana Press.

Layton, Susan. (1994). Russian Literature and Empire:

Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Slezkine, Yuri. (1994). Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small

Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Suny, Ronald Grigor, and Martin, Terry, eds. A State of

Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin

and Stalin. New York: Oxford University Press.

D

ANIEL

B

ROWER

COMINFORM See COMMUNIST INFORMATION BU-

REAU.

COMINTERN See COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL.

COMMAND ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY

The term command administrative economy, or often

administrative command economic system, was

adopted in the late 1980s as a descriptive category

for the Soviet type of economic system. Through-

out its history, the Soviet Union had a mobiliza-

tion economy, focused on rapid industrial

expansion and growth and the development of eco-

nomic and military power, under the direction of

the Communist Party and its leadership. This com-

mand administrative economy evolved from the

experiences of earlier Soviet attempts to develop a

viable socialist alternative to the capitalist market

system that prevailed in the developed Western

world. Thus it was built on the lessons of the non-

monetized pure “command economy” of Leninist

War Communism (1918–1921), Lenin’s experi-

ment with markets under the New Economic

Policy (NEP, 1921–1927), Josef Stalin’s “great So-

cialist Offensive” (1928–1941), war mobilization

(1941–1945) and recovery (1946–1955), and the

Khrushchevian experiment with regional decen-

tralization of economic planning and administra-

tion (1957–1962). This economic system reached

its maturity in the period of Brezhnev’s rule

(1965–1982), following the rollback of the Kosy-

gin reforms of 1967–1972. It provides a concise

summary of the nature of the economic system of

“Developed Socialism” under Brezhnev, against

which the radical economic reforms of perestroika

under Mikhail Gorbachev were directed.

The concept of the command administrative

economy is an elaboration of the analysis of the

command economy, introduced to the study of the

Soviet Union by Gregory Grossman in his seminal

(1963) article, “Notes for a Theory of the Com-

mand Economy.” The term became common in the

economic reform debates of the late Soviet period,

even in the Soviet Union itself, particularly after its

use by the General Secretary of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, at

the reform Party Plenums of January and June

1987, in his critique of the functioning of the So-

viet economic system. The term highlights the fact

that in such an economic system, most economic

activity involves the administrative elaboration and

implementation of commands from superior au-

thorities in an administrative hierarchy, with

unauthorized initiative subject to punishment.

The defining feature of such an economic sys-

tem is the subordination of virtually all economic

activity to state authority. That authority was rep-

resented in the Soviet Union by the sole legitimate

political body, the Communist Party of the Soviet

Union, which necessarily then assumed a leading,

indeed determining, role in all legitimate economic

activity. This authority was realized through a vast

administrative hierarchy responsible for turning

the general objectives and wishes of the Party and

its leadership into operational plans and detailed

implementing instructions, and then overseeing

and enforcing their implementation to the extent

possible. This involved centralized planning that

produced five-year developmental framework plans

and one-year operational directive plans containing

detailed commands mandatory for implementation

COMMAND ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY

291

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

by all subordinate organizations. These plans were

elaborated in increasing detail as they were allo-

cated down the hierarchy, eventually becoming di-

rect specific commands to individual firms, farms,

stores, and other economic organizations.

The task of directive-based centralized planning

in this system was made feasible by aggregation at

higher levels and by the delegation of elaboration

of details of the plan to subordinate levels in the

administrative hierarchy. Thus administrative or-

gans at each level of the hierarchy (central, repub-

lic, regional, local, and operational [e.g., firm, farm,

etc.]) were responsible for planning, supervision,

and enforcement, and engaged in active bargaining

with other levels in the hierarchy to develop an

agreed plan of activity that in general met the needs

and desires of the highest authorities. The result of

this administrative process bore the force of law

and was not subject to legitimate alteration or de-

viation by subordinate units, although higher au-

thorities did have the power to alter or reallocate

the assignments of their subordinates.

To work properly, this system of administra-

tively enforced implementation of commands re-

quires limiting the discretion and alternatives

available to subordinates. Thus the system, within

the areas of activity directly controlled by the state,

was essentially demonetized. Although money was

used as a unit of account and measure of activity,

it ceased to be a legitimate bearer of options in the

state sectors; it failed to possess that fundamental

and defining characteristic of “moneyness”—a uni-

versal command over goods and services. Rather it

played a passive role of aggregating and measur-

ing the flow of economic activity, while plans and

their subsequent allocation documents determined

the ability to acquire goods and services within the

state sector. Similarly, prices in the command ad-

ministrative economy failed to reflect marginal val-

uations, but rather became aggregation weights for

the planning and enforcement of the production

and distribution of heterogeneous products in a

given planned category of activity. Thus in the logic

of the command administrative economy, money

and prices become mere accounting tools, allowing

the administrative hierarchy to monitor, verify, and

enforce commanded performance.

The command administrative system in the So-

viet Union controlled the overwhelming share of

all productive activity. But the experience of war

communism, and the repeated attempts to mobi-

lize and inspire workers and intellectuals to work

toward the objectives of the Soviet Party and State,

showed that the detailed planning and administra-

tion of commands were rather ineffective in deal-

ing with the consumption, career, and work-choice

decisions of individuals and households. The vari-

ety and variability of needs and desires proved too

vast to be effectively managed by directive central

planning and administrative enforcement, except in

extreme (wartime) circumstances. Thus money

was used to provide individual incentives and re-

wards, realizable through markets for consumer

goods and services and the choice of job and pro-

fession, subject to qualification constraints. But

prices and wages were still extensively controlled,

and the cash money allowed in these markets was

strictly segmented from, and nonconvertible with,

the accounting funds used for measuring transac-

tions in the state production and distribution

sectors. This created serious microeconomic dise-

quilibria in these markets, stimulating the devel-

opment of active underground economies that

extended the influence of money into the state sec-

tor and reallocated product from intended planned

purposes to those of agents with control over cash.

The command administrative economy proved

quite effective at forcing rapid industrialization and

urbanization in the Soviet Union. It was effective

at mobilizing human and material resources in the

pursuit of large-scale, quantifiable goals. The build-

ing of large industrial objects, the opening of vast

and inhospitable resource areas to economic ex-

ploitation, and the building and maintenance of

military forces second to none were all facilitated

by the system’s ability to mobilize resources and

focus them on achieving desired objects regardless

of the cost. Moreover, the system proved quite

adept at copying and adapting new technologies

and even industries from the Western market

economies. Yet these very abilities, and the absence

of any valuation feedback through markets and

prices, rendered the operation of the system ex-

tremely costly and wasteful of resources, both hu-

man and material.

Without the ability to make fine trade-offs, to

innovate and to adjust to changing details and cir-

cumstances largely unobservable to those with the

authority in the system to act, the command ad-

ministrative economy grew increasingly inefficient

and wasteful of resources as the economy and its

complexity grew. This became more obvious, even

to the rulers of the system, as microeconomic dis-

equilibria, unfinished construction, unusable in-

ventories, and disruptions of the “sellers’ market,”

COMMAND ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY

292

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY