Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Old-growth forest

logical and regulatory purposes. The task was complicated

by the great diversity in forest types, as well as by different

views of the purpose and use of the definition. For example,

60 years of age might be considered old for one type, whereas

200 or 1,000 years might be more accurate for other types.

Moreover, forest attributes other than age are more impor-

tant for the wellbeing of certain

species

which are dependent

on forests commonly considered old growth, such as the

northern spotted owl

and marbled murrelet. Nonetheless,

some common attributes and criteria were developed.

Old-growth forests are now defined as those in a late

seral stage of ecological succession, based on their composi-

tion, structure, and function. Composition is the representa-

tion of plant species—trees, shrubs, forbs, and grasses—that

comprise the forest. (Often, in referring to an old-growth

stand foresters limit composition to the tree species present).

Structure includes the concentration, age, size, and arrange-

ment of living plants, standing dead trees (called “snags"),

fallen logs, forest-floor litter, and stream debris. Function

refers to the forest’s broad ecological roles, such as

habitat

for terrestrial and aquatic organisms, a repository for genetic

material, a component in the hydrologic and biogeochemical

cycles, and a climatic

buffer

. Each of these factors vary and

must be defined and evaluated for each forest type in the

various physiographic regions, while accounting for differ-

ences in disturbance history, such as wildfires, landslides,

hurricanes, and human activities. The problem of specifically

defining and determining use of these lands is exceedingly

complex, especially for managers of multiple-use public lands

who often are squeezed between the opposing pressures of

commercial interests, such as the timber industry, and envi-

ronmental preservation groups. The modern controversy

centers primarily around forests in the northwest of United

States and Canada—forests consisting of virgin

redwoods

,

Douglas firs, and mixed conifers.

As an example of old-growth characteristics, the

Douglas-fir forests are characterized by large, old, live trees,

many more than 150 feet (46 m) tall, 4 ft (1.2 m) in diameter,

and 200 years old. Interspersed among the trees are snags

of various sizes—skeletons of trees long dead, now home to

birds, small climbing mammals, and insects. Below the giants

are one or more layers of understory—subdominant and

lower growing trees of the same or perhaps different species,

and beneath them are shrubs, either in a thick tangle provid-

ing dense cover and blocking passage or separated and

allowing easy passage. The trees are not all healthy and

vigorous. Some are malformed, with broken tops or multiple

trunks, and infected by fungal rots whose conks protrude

through the bark. Eventually, these will fall, joining others

that fell decades or centuries ago, making a criss-cross pattern

of rotting logs on the forest floor. In places, high in the

trees, neighboring crowns touch all around, permanently

1027

shading the ground; elsewhere, gaps in the canopy allow

sunlight to reach the forest floor.

Proponents of harvesting mature trees in old-growth

forests assert that the forests cannot be preserved, that they

have reached the

carrying capacity

of the site and the stage

of decadence and declining productivity that ultimately will

result in loss of the forests as well as their high commercial

value which supports local lumber-based economies. They

feel that society would be better served by converting these

aged, slow-growing ecosystems to healthy, productive, man-

aged forests. Management proponents also argue that ade-

quate old-growth forests are permanently protected in desig-

nated wildernesses and national and state parks. Moreover,

they point out that even though most old-growth forests are

on

public land

, many forests are privately owned, and that

land owners not only pay taxes on the forests, but they also

have made an investment from which they are entitled a

reasonable profit. If the forests are to be preserved, land

owners and others suffering loss from the preservation should

be reimbursed.

Proponents of saving the large old trees and their

environments claim that the forests are dynamic, that al-

though the largest, oldest trees will die and rot, they also

will be returned to earth to support new growth, foster

biological diversity, and preserve genetic linkages. Moreover,

protection of the forests will help ensure survival of depen-

dent species, some of which are threatened or endangered.

Defenders claim that the trees will not be wasted; they simply

will have alternative value. They believe that their cause is

one of moral as well as biological imperative. More than 90%

of America’s old-growth forests have been logged, depriving

future generations

of the scientific, social, and psychic

benefits of these forests. As a vestige of North American

heritage, the remaining forests, they believe, should be ma-

nipulated only insofar as necessary to protect their integrity

and minimize threats of natural fire or disease from spreading

to surrounding lands. See also American Forestry Associa-

tion; Endangered species; National forest; National Forest

Management Act; Restoration ecology

[Ronald D. Taskey]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Arrandale, T. The Battle for Natural Resources. Washington, DC: Congres-

sional Quarterly, Inc., 1983.

Kaufmann, M. R., W. H. Moir, and R. L. Bassett. Old-Growth Forests in

the Southwest and Rocky Mountain Regions. Proceedings of a Workshop.

Washington, DC: U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range

Experiment Station, 1992.

O

THER

Spies, T. A., and J. F. Franklin. “The Structure of Natural Young, Mature,

and Old-Growth Douglas-Fir Forests in Oregon and Washington.” In

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Oligotrophic

Wildlife and Vegetation of Unmanaged Douglas-Fir Forests, edited by L. F.

Ruggiero, et al. Washington, DC: U. S. Forest Service, Pacific Northwest

Forest and Range Experiment Station, 1991.

Oligotrophic

The term oligotrophic is derived from the Greek term

meaning “poorly nourished” and refers to an aquatic system

that has low overall levels of primary production, principally

because of low concentrations of the nutrients that plants

require. The bottom waters of an oligotrophic lake do not

become depleted of oxygen in summer, when rates of

pri-

mary productivity

in surface waters of the lake are typically

at their highest. Oligotrophic bodies of water tend to have

a more diverse community of

zooplankton

than waters with

high levels of primary production. The term can also be used

to describe any organism that only needs a limited supply

of nutrients, or an insect that only utilizes a few plants as

habitat

.

[Marie H. Bundy]

Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. (1822 –

1903)

American landscape designer

The famous landscape designer of Central Park (on which

he collaborated with the architect Calvert Vaux), Frederick

Law Olmsted Sr. is widely known for that accomplishment

alone. Considering the impact of the park on city life in

New York, and on other designs around the world, that

would be accomplishment enough. But Olmsted other

achievements are so overshadowed by the Central Park proj-

ect, that he is still not as well known in environmental circles

as he should be.

Many people don’t know, or are confused by, the fact

that there were two Frederick Law Olmsteds: father and

son, F. L. O Sr., and F. L. O Jr. Both of them were landscape

architects, and F. L. O Jr. followed directly in his father’s

footsteps, assuming “leadership of the country’s largest and

most prestigious landscape architecture firm” after his fa-

ther’s death.

Olmsted Sr., was born in “the rural environs” of Hart-

ford, Connecticut, the oldest son of a well-to-do merchant,

from an old New England family. He was educated in a

series of boarding schools in the rural Connecticut area where

he grew up. More unorthodox educational benefits accrued

from his apprenticeships as civil engineer and farmer along

with his stint as a ship’s cabin boy on a trip to China.

Reportedly, Olmsted’s firm laid out some 1,000 parks

in 200 cities. He also designed university campuses (U.C.

1028

Berkeley, Harvard, Amherst, Yale, etc.), cemeteries, hospital

grounds (including the grounds for the hospital where he

died, unhappy—even while suffering a terminal illness—

that his plans for the hospital had not been followed carefully

enough). A source of unhappiness in general was the fact

that many of his plans were modified in ways he did not

agree with (e.g., Stanford University), or even suppressed,

as happened with his plan for

Yosemite National Park

.

The crown jewel of Olmsted’s creativity is, of course,

Central Park in New York City. As Bill Vogt describes it:

“the entire area was man-made, literally from the ground

up. It sprang from an 843-acre eyesore of stinking quagmire,

rubbish heaps, rocky outcroppings, and squatters shacks.”

An army of workers created a lake, shoveled in enormous

quantities of top

soil

to create natural-appearing meadows,

and planted whole forests to screen the park from the city.

Charles McLaughlin, the editor of Olmsted’s papers,

claimed that one of the reasons Olmsted was virtually forgot-

ten for so long was that his designs have an “always been

there” quality, resulting in landscapes that today “in their

maturity...appear so ’natural’ that one thinks of them as

something not put there by artifice but merely preserved by

happenstance.” What Olmsted and Vaux created stands to-

day as an oasis and respite from what Olmsted described as

the city’s “constantly repeated right angles, straight lines,

and flat surfaces.”

Among Olmsted’s lesser known accomplishments

were both his role in the Commission to establish Yosemite

Park (a task undertaken in 1864, long before

John Muir

first saw Yosemite Valley) and preserve Niagara Falls, a

movement which resulted in creation of the Niagara Falls

State Reservation in 1888. He also was a prominent partici-

pant in the campaign to preserve the Adirondack region in

upstate New York.

Even less well known are his writings not directly

associated with landscape architecture or ecological design.

Olmsted was quite an accomplished travel writer, producing

still readable books like a Saddle-trip on the Southwestern

Frontier of Texas, or his first book titled Walks and Talks of

an American Farmer in England. Olmsted’s travels in the

South were as a roving journalist for the New York [Daily]

Times; he was an acute observer and his travel books on the

south were also commentaries on the institution of slavery

(that he believed “to be both economically ruinous and mor-

ally indefensible.") Books from this period included The

Cotton Kingdom: A Traveler’s Observations on Cotton and

Slavery in the American Slave States, A Journey in the Seaboard

Slave States, and Slavery and the South, 1852–1857.Hewas

also a founder of the liberal journal of commentary, The

Nation. He never dissociated his design work from its social

context (believing, in his words, that his works should have “a

manifest civilizing effect"), and his biggest disappointments

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Open marsh water management

occurred when he was not allowed to incorporate his ideas

on social change into his various designs.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Beveridge, C. E., and P. Rocheleau. Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing the

American Landscape. New York: Rizzoli, 1995.

Fein, A. Frederick Law Olmsted and the American Environmental Tradition.

New York: George Braziller, 1972.

Hall, L. Olmsted’s America. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995.

Kalfus, M. Frederick Law Olmsted: The Passion of a Public Artist. New York:

New York University Press, 1990.

Olmsted, F. L. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Ed. C. C. McLaughlin.

Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

White, D. F. “Frederick Law Olmsted, Placemaker.” Two Centuries of

American Planning. Ed. Daniel Schaffer. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1988.

Onchocerciasis

see

River blindness

OPEC

see

Organization of Petroleum Exporting

Countries

Open marsh water management

Open Marsh Water Management (OMWM) refers to the

practice of controlling the mosquito population in salt

marshes by creating an appropriate

habitat

for the natural

enemies of the mosquitoes; and by reducing

flooding

in

areas that are not wet on an ordinary basis—thus reducing

an

environment

that would support mosquitoes but not

their predators. Without use of

chemicals

that might be

harmful to the

natural resources

surrounding the water

body, as well as harmful to

wildlife

and humans, OMWM

calls on nature’s own ecological balance in order to success-

fully alter the pest—mosquito. The techniques were eventu-

ally employed by individuals and municipalities in order to

control mosquitoes even in their own backyards, no matter

how far that might be from tidal

wetlands

.

Before this plan was developed, and first used in New

Jersey to control the mosquito problem in their tidal wetlands

and marshes, the normal practice utilized a network of

ditches. Under this method, which started around the time

of the Civil War, the shallow ponds and water pools, the

natural habitats of the birds and fish that fed on mosquitoes

were changed or destroyed through ditch digging to drain

the marshes and remove standing water. According to the

1029

Conservationist in an article published in June 1997, the

digging also created a problem because, “Spoil generated by

the ditch digging was often disposed of in marsh areas,

creating high areas. The high areas were soon invaded by

reeds and shrubs—vegetation of lesser value for marsh wild-

life. In addition

spoil

mounds restricted the ebb and flow

of tides, reducing flushing and creating habitat that actually

favored mosquitoes. Many marshes became cut off from

tidal flow, causing them to gradually become less saline

[salty]. This resulted in changes in the composition of

flora

and

fauna

, enabling such non-native plants as the common

reed (Phragmites) to invade the marsh. While somewhat

attractive and often collected for dry plant arrangments,

this plant has little wildlife value and displaces other more

valuable species.”

The key to OMWM is creating a habitat for one

particular mosquito predator, the mummichogs, or marsh

killfish. By restoring the body of water to its natural state,

marsh killfish are provided with a habitat for survival, as are

other fish and wildlife. The killfish are small but have appe-

tites for mosquito larvae that never subside. Natural habitats

are created by the tidal flow that go between being pools of

deep water and shallow ponds. Killfish thrive under these

conditions—laying their eggs when it is dry, and hatching

them when it floods. The mosquito produces a vast number

of larvae (all waiting to emerge as mosquitoes) as soon as

the marshes are once again full of water. Yet simply produc-

ing more killfish does not ensure that they will reach the

mosquitoes, and thus control the population. Again, the

Conservationist has pointed out that, “For a project to be

effective over a wide tidal range, the design of the tidal

channels must be carefully tailored to the specific conditions

of the marsh. Shallow access channels are constructed to

allow the fish access to all parts of the marsh surface. How-

ever, pool and ditch sections must provide enough water

and adequate depth to prevent excessive predation of the

fish by wading birds.”

Mosquito control in history

The state of New Jersey was the first place where

OMWM was used—and the reasons for that go as far back

as the early settlers. According to the New Jersey Mosquito

Homepage (NJMH) Yellow Fever, contracted from mosqui-

toes, was the known as the “American plague,” infecting the

Massachusetts colony as early as 1647. In 1793, Philadelphia

was hit and the city’s population was devastated. When an

army surgeon named

Walter Reed

finally traced the

virus

to the mosquito, Aedes aegypti, in 1900, the disease was

dealt a death blow like the one it once had wagered on its

victims. But the mosquito remained more than a simple

annoyance that even the window screen introduced in the

1880s could not totally erase. Humans could contract

East-

ern Equine Encephalitis

through mosquitoes, a disease of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Open marsh water management

epidemic proportions even into the middle half of the twenti-

eth century. Horses continue to be infected if they are not

inoculated against the disease. Mosquitoes can also transmit

heartworm disease to dogs. Even in modern-day America,

a variety of the

species

has been found to infect humans

with the deadly

West Nile Virus

causing illness and death

to wildlife and people from New York to Ohio, and down

the east coast, by 2002.

The NJMH elaborates further on the history of mos-

quito control as an early priority in that state, and others.

“Considerable public debate was given to the question

whether mosquitoes could ever be controlled. Mosquito con-

trol operations grew in some towns but not in all towns.

Newspaper battles raged when it was painfully noted that

mosquitoes ignored municipal and even state borders. Local

boards of health funded most of the extermination work.

Laws in 1906 required support for local efforts from the

state experiment station. Another law in 1912 directed the

creation of county mosquito extermination commissions to

assure full-time mosquito work With an increase in mosquito

control workers and their rapid progress, it became clear

than an organization was needed within which these workers

could discuss their problems and share their experiences.”

Following the first convention of county commission in

February 1914 in Atlantic City, the permanent organization

known as the

New Jersey Mosquito Extermination Asso-

ciation

was formed. In 1935, a regional organization was

formed with ten other states, the

Eastern Association of

Mosquito Control Workers

, from a meeting at Trenton;

it was re-named in 1944. The

American Mosquito Control

Association

remains the premier organization concerned

with mosquito control.

The common salt marsh mosquitoes include those

known as Aedes sollicitans; Aedes contator,; and, Aedes taenior-

hynchus. Adult females deposit their eggs on the marsh sur-

face, which dry for 24 hours. The egg-filled depressions fill

with water during the monthly high tides when the marsh

is flooded, causing the larvae to hatch quickly. In addition

to killfish acting as predators for the larvae, they can be

controlled through the OMWM technique of utilizing a

series of ditches to connect mosquito breeding depressions

to more permanent bodies of water. It eliminates standing

water, and also provides for predator fish to reach any mos-

quito larvae that is still there.

One example of a project to turn around the results

of the former ditch digging practice that had been used and

proven harmful(see History of to the natural environment

is a research project operating in 2000, and supervised by

the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

(USFWS), Region 5,

at the Rachel Carson

Wildlife Refuge

in Maine. The

U.S.

Department of the Interior

, U.S.

Geological Survey

in-

formation system project of the Patuxent Wildlife Research

1030

Center in Laurel, MD provided a history and description

of the project. “By the 1930s, most salt marshes throughout

the northeastern United States had been ditched for mos-

quito control purposes. Documented impacts of this exten-

sive network of ditching include

drainage

of marsh pools,

lowered

water table

levels, vegetation changes, an associ-

ated trophic [feeding ] responses. To restore the ecological

functions of ditched salt marshes, while maintaining effective

mosquito control, the USFWS (Region 5) is in the process

of plugging the salt marsh ditches and establishing marsh

pools. Ditch plugging is an adaptation of the mosquito con-

trol practice known as Open Marsh Water Management.

The purpose of this proposed study is to compare and evalu-

ate marshes that have been ditch plugged with unditched

and parallet ditched marshes. Physical (tidal

hydrology

,

water table level), chemical (

soil salinity

), and ecological

(vegetation,

nekton

, marsh invertebrates, waterbirds, mos-

quito production) factors will be evaluated.” Before data

could be collected, whatever the results, this study was ex-

pected to create an established pattern for long-term salt

marsh monitoring.

East coast states, as well as areas around the country,

have engaged in OMWM not merely for simple mosquito

control; but as a part of the restoration of

estuaries

and other

wildlife management

and restoration projects. OMWM

techniques were still being refined as of 2002 as part of a

return to an ecologically-balanced system that provides for

the survival of natural resources, and for the survival of

humans and wildlife.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

“Tidal Wetlands in New York State Diversity.” Conservationist 51, no. 6

(June 1997): 4.

O

THER

“Cape May County Mosquito Extermination Commission.” Cape May

County Web Page. 2001 [June 2002]. <http://www.capemaycountygov.net>.

“Coastal Mosquito Control in Your Neighborhood.” Norfolk County Mos-

quito Control Project. May 3, 2001 [June 2002]. <http://www.ultranet.com/

~ncmcp/>.

“Connecticut River Estuary and Tidal River Wetlands Complex.” State

of Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection. 2002 [July 2002].

<http://www.dep.state.ct.us>.

James-Pirri, Mary Jane. “Mosquito Beach Salt Marsh OMWM Restora-

tion.” Northeastern Mosquito Control Association. 2002 [July 2002]. <http://

www.nmca.org>.

Johnson, David. “Africana.” Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. July 25, 2000

[cited June 2002]. <http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/>.

“Mosquito Breeding Habitats.” Monmouth County, NJ Web Page. 1999 [June

2002]. <http://www.visitmonmouth.com>.

Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Research Project; Ecosystem response of

salt marshes to Open Marsh Water management (OMWM): Rachel Carson

National Wildlife Refuge (Maine). “Angolan deepwater fields emerge as

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Opportunistic organism

world’s most exciting oil frontier.” 2001. (June 2002). <http://www.internat-

ionalspecialreports.com/>

Purdue University/Forestry and Natural Resources. Did You Know? Healthy

Wetlands Devour Mosquitoes? [cited June 2002]. <http://www.agriculture.-

purdue.edu/fnr>.

Rutgers University/Entomology. “History of Mosquito Control in New

Jersey (Where it all Began).” New Jersey Mosquito Control Homepage. [cited

June 2002]. <http://www.-rci.rutgers.edu/~insects/>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.,

Washington, DC USA 20460 202-260-2090, <www.epa.gov>

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. USA , <www.fws.gov>

Open system

The relationship between any system and its surrounding

environment

can be described in one of three ways. In an

isolated system, neither matter nor energy is exchanged with

its environment. In a closed system, energy, but not matter,

is exchanged. In an open system, both matter and energy

are exchanged between the system and its surrounding envi-

ronment. Any

ecosystem

is an example of an open system.

Energy can enter the system in the form of sunlight, for

example, and leave in the form of heat. Matter can enter

the system in many ways. Rain falls upon it and leaves by

evaporation or streamflow, or animals migrate into the sys-

tem and leave in the form of decay products.

Opportunistic organism

Opportunistic organisms commonly refer to animals and

plants that tolerate variable environmental conditions and

food sources. Some opportunistic

species

can thrive on al-

most any available

nutrient

source: omnivorous rats, bears,

and raccoons are all opportunistic feeders. Many opportun-

ists flourish under varied environmental conditions: the com-

mon house sparrow (Passer domesticus) can survive both in

the warm, humid

climate

of Florida and in the cold, dry

conditions of a Midwestern winter. Aquatic opportunists,

often aggressive fish species, fast-spreading

plankton

, and

water plants, frequently tolerate fluctuations in water

salin-

ity

as well as temperature.

A secondary use of the term “opportunistic” signifies

species that can quickly take advantage of favorable condi-

tions when they arise. Such species can postpone reproduc-

tion, or even remain dormant, until appropriate tempera-

tures, moisture availability, or food sources make growth and

reproduction possible. Some springtime-breeding lizards in

Australian deserts, for example, can spend months or years

in a juvenile form, but when temperatures are right and a

rare rainfall makes food available, no matter what time of

year, they quickly mature and produce young while water is

1031

still available. More familiar opportunists are viruses and

bacteria that reside in the human body. Often such organisms

will remain undetected with a healthy host for a long time.

But when the host’s immune system becomes weak, resident

viruses and bacteria seize an opportunity to grow and spread.

Thus people suffering from malnutrition, exhaustion, or a

prolonged illness are especially vulnerable to common oppor-

tunistic diseases such as the common cold or pneumonia.

Adaptable and prolific reproductive strategies usually

characterize opportunistic organisms. While some plants can

reproduced only when pollinated by a specific, rare insect

and many animals can breed only in certain conditions and

at a precise time of year, opportunistic species often repro-

duce at any time of year or under almost any conditions.

House mice (Mus musculus) are extremely opportunistic

breeders: they can produce sizeable litters at any time of

year. Opportunistic feeding aids their ability to breed year

round; these mice can nourish their young with almost any

available vegetable matter, fresh or dry.

The common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) is also

an opportunistic breeder. Producing thousands of seeds per

plant from early spring through late fall, the dandelion can

reproduce despite

competition

from fast-growing grass, un-

der heavy applications of chemical herbicides, and even with

the violent weekly disturbance of a lawn mower. Once ma-

ture, dandelion seeds disperse rapidly and effectively, riding

on the wind or on the fur of passing rodents. The common

housefly (Musca domestica) is also an opportunistic feeder

and reproducer—it can both feed and lay eggs on almost

any organic material as long as it is fairly warm and moist.

Because of their adaptability, opportunistic organisms

commonly tolerate severe environmental disturbances. Fire,

floods,

drought

, and

pollution

disturb or even eliminate

plants and animals that require stable conditions and have

specialized nutrient sources. Fireweed (Epilobium angustifol-

ium), an opportunist that readily takes advantage of bare

ground and open sunlight, spreads quickly after land is

cleared by fire or by human disturbance. Because they toler-

ate, or even thrive, in disturbed environments, many oppor-

tunists flourish around human settlements, actively ex-

panding their ranges as human activity disrupts the

habitat

of more sensitive animals and plants. Opportunists are espe-

cially visible where chemical pollutants contaminate habitat.

In such conditions overall species diversity usually declines,

but the population of certain opportunistic species may in-

crease as competition from more sensitive or specialized

species is eliminated.

Because they are tolerant, prolific, and hardy, many

opportunistic organisms, including the house fly, the house

mouse, and the dandelion, are considered pests. Where they

occur naturally and have natural limits to their spread, how-

ever, opportunists play important environmental roles. By

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Orangutan

quickly colonizing bare ground, fireweed and opportunistic

grasses help prevent

erosion

. Cottonwood trees (Populus

spp.), highly opportunistic propagators, are among the few

trees able to spread into

arid

regions, providing shade and

nesting places along stream channels in deserts and dry

plains. Some opportunists that are highly tolerant of pollu-

tion are now considered indicators of otherwise undetected

chemical spills

. In such hard-to-observe environments as

the sea floor, sudden population explosions among certain

bottom-dwelling marine mollusks, plankton, and other in-

vertebrates have been used to identify

petrochemical

spills

around drilling platforms and shipping lanes. See also Adap-

tation; Contaminated soil; Environmental stress; Flooding;

Growth limiting factors; Indicator organism; Parasites; Re-

silience; Scavenger; Symbiosis

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Foster, H. D. Health, Disease and the Environment. Boca Raton: CRC

Press, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Alexander, S. P. “Oasis Under the Ice.” International Wildlife 18 (Novem-

ber-December 1988): 32–7.

Arcieri, D. T. “The Undesirable Alien—The House Sparrow.” The Conser-

vationist 46 (1992): 24–25.

Bradshaw, S. D., H. S. Giron, and F. J. Bradshaw. “Patterns of Breeding

in Two Species of Agamid Lizards in the Arid Subtropical Pilbara Region

of Western Australia.” General and Comparative Endocrinology 82 (1991):

407–24.

Moreno, J. M., and W. C. Oechel. “Fire Intensity Effects on Germination

of Shrubs and Herbs in Southern California Chaparral.” Ecology 72 (1991):

1993–2004.

Shafir, A. “Dynamics of a Fish Ectoparasite Population: Opportunistic

Parasitism in Argulus japonicus.” Crustaceana 62 (1992): 50–64.

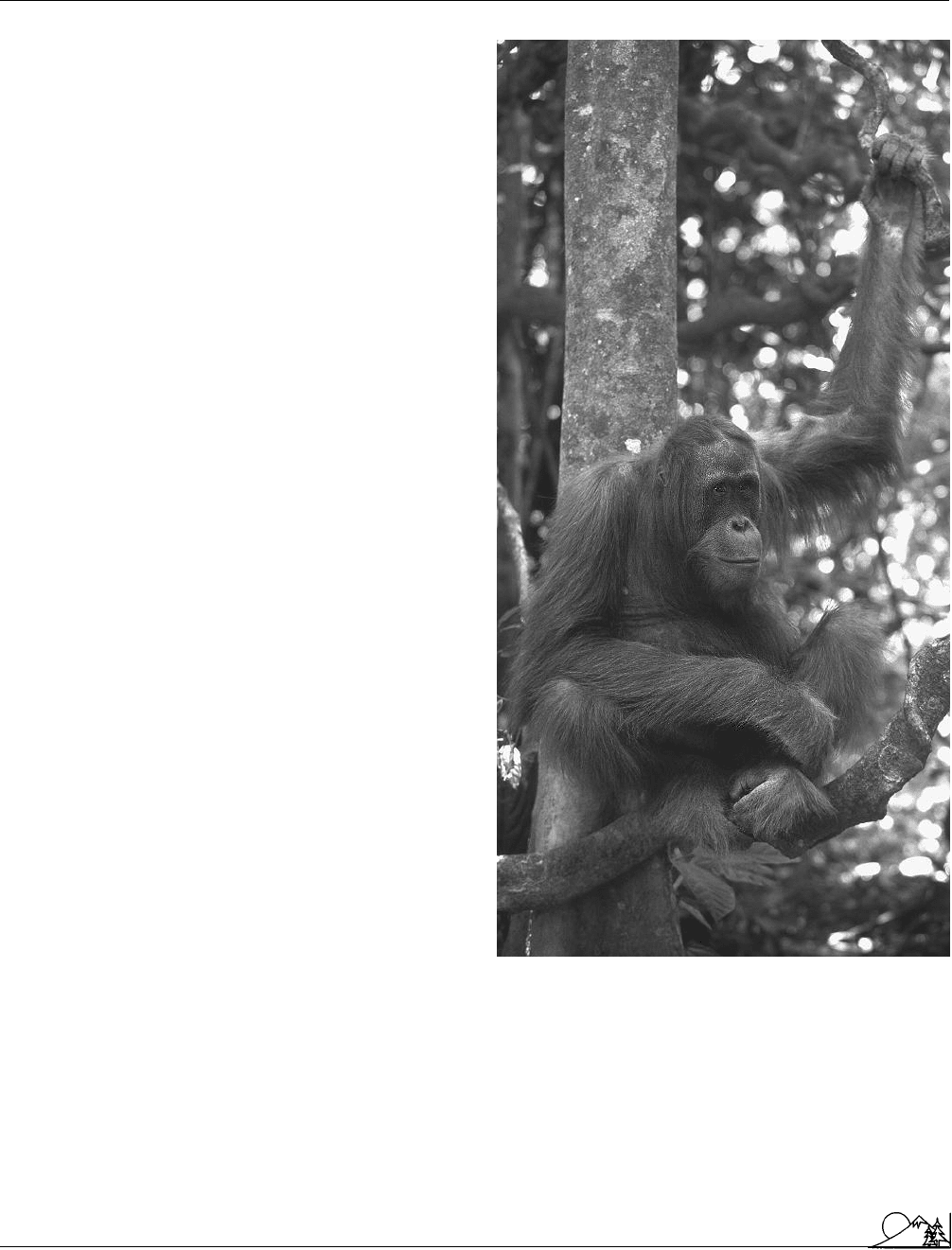

Orangutan

The orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), one of the Old World

great apes, has its population restricted to the rain forests

of the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo. The

orangutan is the largest living arboreal mammal, and it

spends most of the daylight hours moving slowly and deliber-

ately through the forest canopy in search of food. Sixty

percent of their diet consists of fruit, and the remainder is

composed of young leaves and shoots, tree bark, mineral-

rich

soil

, and insects. Orangutans are long-lived, with many

individuals reaching between 50 and 60 years of age in the

wild. These large, chestnut-colored, long-haired apes are

facing possible

extinction

from two different causes:

habitat

destruction and the wild animal trade.

1032

An orangutan. (Photograph by Tim Davis. Photo Re-

searchers Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

The

rain forest ecosystem

on the islands of Sumatra

and Borneo is rapidly disappearing. Sumatra loses 370 mi

2

(960 km

2

) of forest a year, or about 1.6%, faster than any

other Indonesian island. The rest of central Indonesia, of

which Borneo comprises a major part, loses about 2,700

square miles (7,000 km

2

) per year. Some experts believe this

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Oregon silverspot butterfly

estimate is too low, and they argue it could be closer to

4,600 mi

2

(12,000 km

2

) per year. Another devastating blow

was dealt Borneo’s rain forests just over a decade ago, when

more than 15,400 mi

2

(40,000 km

2

) of the island’s tropical

forest was destroyed by

drought

and fire between 1982 and

1983. The fire was set by farmers who claimed to be unaware

of the risks involved in burning off vegetation in a drought

stricken area. Even though Indonesia still has over 400,000

mi

2

(1,000,000 km

2

) of rain forest habitat remaining, the

rate of loss threatens the continued existence of the wild

orangutan population, which is now estimated at about

25,000 individuals.

Both the Indonesian government and the

Convention

on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild

Fauna and Flora

(CITES) have banned international trade

of orangutans, yet their population continues to be threat-

ened by the black market. In order to meet the demand for

these apes as pets around the world, poachers kill the mother

orangutan to secure the young ones, and the

mortality

rate

of these orphans is extremely high, with less than 20% of

those smuggled ever arriving alive at their final destination.

This high mortality rate is directly due to stress, both emo-

tional and physiological, on the young orangutans. The

transportation

scheme involved in smuggling these animals

out of Indonesia to major trade centers throughout the world

is intricate and time-consuming, and the way in which they

are concealed for shipping is inhumane. These are two more

reasons why only one out of five or six orangutan babies will

survive the ordeal.

Some hope for the

species

rests in a global effort to

manage a captive propagation program in zoos. A potentially

self-sustaining captive population of more than 850 orang-

utans has been established. An elaborate system of net-

working and recording of all legally held individuals may also

aid in the recognition and recapture of smuggled animals.

Researchers have also developed methods of determining

whether smuggled orangutans are of Bornean or Sumatran

origin, thus providing a means of maintaining genetic integ-

rity for those that can be bred in captivity or relocated.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Galdikas, M. F. Birute

´

, and Nancy Brigs. Orangutan Odyssey. New York:

Harry N. Abrams, 1999.

Russon, Anne. Orangutans: Wizards of the Rain Forest. Buffalo: Firefly

Books, 2000.

O

THER

Orangutan Sanctuary. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.yorku.ca/arusson>.

Orang-outang. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.orang-outang.com>.

1033

Order of magnitude

A mathematical term used loosely to indicate tenfold differ-

ences between values. This concept is crucial to interpreting

logarithmic scales such as

pH

or

earthquake

magnitude,

where each number differs by a factor of 10, and two numbers

differ by a factor of 100 (10 times 10). For example, a pH

of 4 is 100 times as acidic as a pH of 6 because they differ

by two orders of magnitude. Scientists often generalize with

this term; for example “our ability to measure pollutants

has improved by several orders of magnitude” means that

whereas before we were able to measure

parts per million

(ppm), we can now measure

parts per billion

(ppb).

Oregon silverspot butterfly

The Oregon silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene hippolyta)is

a medium-sized butterfly, predominantly orange and brown

with black veins and spots on its hindwings and bright silver

spots on its forewings. The length of its forewings is about

1.1 in (2.9 cm). The female is usually slightly larger than

the male. This butterfly is listed as threatened by the U. S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

and has been protected under

the

Endangered Species Act

since 1980.

Inhabiting a very restricted range, the Oregon sil-

verspot occurs only in salt spray meadows along the Pacific

coast in Oregon and Washington. This

habitat

is character-

ized by heavy rainfall, fog, and mild temperatures. The most

critical feature of this habitat, however, is the presence of

the western blue violet (Viola adunca), the host plant of the

butterfly’s larva. For two months each spring, larval Oregon

silverspots feed on violet leaves before entering the pupa

stage of development. This butterfly was historically present

at 17 locations along the coasts of Oregon and Washington,

but now only five populations in Oregon are known to exist

with certainty.

Housing developments and recreational uses of the

coast that destroy or degrade butterfly habitat are the major

threats to this subspecies’s survival. Natural fire patterns in

its meadow habitat have been suppressed, allowing non-

native vegetation to mix with native plants and changing

the habitat’s character. An area of Lane County, Oregon

with a healthy population of Oregon silverspots has been

designated

critical habitat

for this subspecies. Expansion

of the population of western blue violets in this area will be

encouraged by the control of saplings and other invading

plants. Transplantation of western blue violets to other sites

with suitable meadow habitat may also be attempted. A

recovery plan was put into effect in 1999 and monitored

through 2000. It was headed by Lewis and Clark College,

the Oregon Zoo in Portland, and the Woodland Park Zoo

in Seattle and consisted of rearing the larvae in captivity,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Organic gardening and farming

Oregon silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene

hippolyta). (Photograph by Paul A. Opler. Reproduced

by permission.)

then returning the butterflies to the wild. Although the

Oregon silverspot butterfly is not in immediate danger of

extinction

, its specific habitat requirements and the vulnera-

bility of that habitat to degradation and destruction, makes

intervention necessary to ensure the long-term survival of

this subspecies.

[Christine B. Jeryan]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Howe, W. H. The Butterflies of North America. Garden City, NY: Double-

day, 1975.

O

THER

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Revised Recovery Plan Published for the

Oregon Silverspot Butterfly. November 29, 2001 [cited May 2002]. <http://

news.fws.gov/NewsReleases/R1/C71501ED-5742-4E26-

965408A77BC0875F.html>.

Organic gardening and farming

Agriculture has changed dramatically since the end of World

War II. As a result of new technologies, mechanization, in-

creased chemical use, specialization, and government policies,

food and fiber productivity has soared. While some of these

changes have ledto positive effects, there have been significant

costs:

topsoil

depletion,

groundwater

contamination,

harmful

pesticide residue

, the decline of family farms, and

increasing costs of production.To counterbalance these costs,

there is a growing movement to grow plants organically.

On a local level, suburban homeowners and city dwell-

ers are finding ways to plant their own food for personal

consumption in plots that are not sprayed with

chemicals

1034

or treated with synthetic fertilizers. City dwellers may team

up to work a collective, organic garden on a vacant lot.

Homeowners have the option to create

mulch

piles—a mix-

ture of leaves and organic materials, vegetable leavings, egg

shells, coffee grounds, etc.—that eventually become a rich

soil

, thanks to the breakdown of these elements by tiny

organisms. This enriched soil becomes a fertile, clean foun-

dation for a bountiful garden. The inevitable weeds that

grow can be picked by hand.

On a larger level, emerging as an answer to some of

these farming problems is a movement called “sustainable

agriculture.” Sustainability rests on the principle that we

must meet the needs of the present without compromising

the ability of

future generations

to meet their own needs.

Organic farming is part of this movement. Most sig-

nificantly, organic foods are grown without synthetic fertiliz-

ers, pesticides, or herbicides. Organic farming and gardening

is the result of the belief that the best food crops come from

soil that is nurtured rather than treated. Organic farmers

take great care to give the soil nutrients to keep it healthy,

just as a person works to keep his or her body healthy with

certain nutrients. Thus, organic farmers prefer to provide

those essential soil builders in natural ways: using cover crops

instead of chemical fertilizers, releasing predator insects

rather than spraying pests with pesticides and hand weeding

rather than applying herbicides.

Organic production practices involve a variety of farm-

ing applications. Specific strategies must take into account

topography

, soil characteristics,

climate

, pests, local avail-

ability of inputs, and the individual grower’s goals. Despite

the site-specific and individual nature of this approach, sev-

eral general principles can be applied to help growers select

appropriate management practices. Growers must:

1. Select

species

and varieties of crops that are well

suited to the site and to the conditions of the farm.

2. Diversify the crops, including livestock and cultural

practices, to enhance the biological and economic

stability

of the farm.

3. Manage the soil to enhance and protect its quality.

Making the transition to

sustainable agriculture

is

a process. For farmers, the transition normally requires a

series of small, realistic steps. For example in California,

where there has been a water shortage, steps are being taken

to develop drought-resistant farming systems, even in normal

years. Farmers are encouraged to improve

water conserva-

tion

and storage measures, provide incentives for selecting

specific crops that are drought-tolerant, reduce the volume

of

irrigation

systems, and manage crops to reduce water loss.

In order to stop soil

erosion

, farmers are encouraged

to reduce or eliminate tillage, manage irrigation to reduce

runoff

, and keep the soil covered with plants or mulch.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Organic gardening and farming

Farmers are also encouraged to diversify, since diversi-

fied farms are usually more economically and ecologically

resilient. By growing a diversity of crops, farmers spread

economic risk and the crops are less susceptible to the infesta-

tion of certain predators that feed off one crop. Diversity can

buffer a farm biologically. For example, in annual cropping

systems, crop rotation can be used to suppress weeds, patho-

gens, and insect pests.

Cover crops can have a stabilizing effect on the agro-

ecosystem

. Cover crops hold soil and nutrients in place,

conserve soil moisture with mowed or standing dead

mulches, and increase the water

infiltration

rate and soil

water holding capacity. Cover crops in orchards and vine-

yards can buffer the system against

pest

infestations by

increasing beneficial arthropod populations and can there-

fore reduce the need for chemicals. Using a variety of cover

crops is also important in order to protect against the failure

of a particular species to grow and to attract and sustain a

wide range of beneficial arthropods.

Optimum diversity may be obtained by integrating

both crops and livestock in the same farming operation. This

was the common practice for centuries until the mid-1900s,

when technology, government policy, and economics com-

pelled farms to become more specialized. Mixed crop and

livestock operations have several advantages. First, growing

row crops only on more level land and pasture or forages

on steeper slopes will reduce soil erosion. Second, pasture

and forage crops in rotation enhance soil quality and reduce

erosion; livestock manure in turn contributes to soil fertility.

Third, livestock can buffer the negative impacts of low rain-

fall periods by consuming crop residue that in “plant only”

systems would have been considered failures. Finally, feeding

and marketing are more flexible in animal production sys-

tems. This can help cushion farmers against trade and price

fluctuations and, in conjunction with cropping operations,

make more efficient farm labor.

Animal production practices are also sustainable or

organic. In the midwestern and northeastern United States,

many farmers are integrating crop and animal systems, either

on dairy farms or with range cattle, sheep, and hog opera-

tions. Many of the principles outlined in the crop production

section apply to both groups. The actual management prac-

tices will, of course, be quite different.

Animal health is crucial, since unhealthy stock waste

feed and require additional labor. A herd health program is

critical to sustainable livestock production. Animal nutrition

is another major issue. While most feed may come from

other enterprises on the ranch, some purchased feed is usually

imported. If the animals feed from the outside, this feed

should be as free of chemicals as possible.

A major goal of organic farming is a healthy soil.

Healthy soil will produce healthy crops and plants that have

1035

optimum vigor and less susceptibility to pests. In organic or

sustainable systems, the soil is viewed as a fragile and living

medium that must be protected and nurtured to ensure its

long-term productivity and stability. Fertilizers and other

inputs may be needed, but they are minimized as the farmer

relies on natural, renewable, and on-farm inputs.

While many crops have key pests that attack even

the healthiest of plants, proper soil, water, and

nutrient

management can help prevent some pest problems brought

on by crop stress or nutrient imbalance. Additionally, crop

management systems that impair soil quality often result in

greater inputs of water, nutrients, pesticides, and/or energy

for tillage to maintain yields.

Sustainable approaches are those that are the least

toxic and least energy intensive and yet maintain productivity

and profitability. Farmers are encouraged to use preventive

strategies and other alternatives before using chemical inputs

from any source. However, there may be situations where

the use of synthetic chemicals would be more “sustainable”

than a strictly nonchemical approach or an approach using

toxic “organic” chemicals. For example, one grape grower

in California switched from tillage to a few applications of

a broad spectrum contact

herbicide

in his vine row. This

approach may use less energy and may compact the soil less

than numerous passes with a cultivator or mower.

Coalitions have been created to address the growing

organic movement concerns on a local, regional, and national

level. The Organic Food Production Association of North

America is the trade and marketing arm of the organic

industry in the United States and Canada. The Farm Bill

of 1990—Organic Foods Production Act—addressed the

growing organic farming movement. Title 21 of the bill is

the section that will be dealing with the regulations regarding

organic certification. The

U.S. Department of Agriculture

,

with the guidance of an advisory committee or National

Organic Standards Board, is in the process of establishing

the federal regulations that will standardize the rules for the

entire organic industry in the United States, from growing

and manufacturing to distribution. Presently, the organic

movement includes growers, retailers, distributors, traders,

urban and individual consumers, processors, and various

nonprofit organizations nationwide.

Until the regulations are in place, the standards estab-

lished by individual states vary, or in some states do not

exist at all. The 1990 law requires that organic farmers wait

for three years before they are officially certified—to ensure

most of the chemicals have been eliminated. With proper

documentation, on-site inspectors are then able to certify

the farm. Organic groups admit that no organic program

can claim absolutely it is residue free. The issue here is a

process—of farming and producing product in as chemically

free and healthy an

environment

as is possible.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Organic waste

The international community is joining the organic

movement. Europe—the European Common Market—

Australia, Argentina, and many countries in South America

are establishing their own organic standards and have joined

together under the organization called International Federa-

tion of Organic Agricultural Movements.

In addition to the upcoming United States federal

standardization of organic farming, more policies are needed

to promote simultaneously

environmental health

and eco-

nomic profitability.

For example, commodity and price support programs

could be restructured to allow farmers to realize the full

benefits of the productivity gains made possible through

alternative practices. Tax and credit policies could be modi-

fied to encourage a diverse and decentralized system of family

farms rather than corporate concentration and absentee own-

ership. Government and land grant university research could

be modified to emphasize the development of sustainable

alternatives. Congress can become more rigorous in pre-

venting the application of certain pesticides, especially those

that have been shown to be carcinogenic. Marketing orders

and cosmetic standards (i.e. color and uniformity of product,

etc.) could be amended to encourage reduced

pesticide

use.

Consumers play a key role. Through their purchases,

they send strong messages to producers, retailers, and others

in the system about what they think is important. Food

cost and nutritional quality have always influenced consumer

choices. The challenge now is to find strategies that broaden

consumer perspectives so that environmental quality and

resource use are also considered in shopping decisions. Coali-

tions organized around improving the food system are one

specific method of systemizing growing and delivery for the

producers, retailers, and consumers.

“Clean” meat, vegetables, fruits, beans, and grains are

available, as are products such as organically grown cotton.

As consumer demands increase, growers will respond. See

also Biodiversity; Monoculture

[Liane Clorfene Casten]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Conford, P., ed. Organic Tradition: An Anthology of Writings on Organic

Farming, 1900–1950. Cincinnati, OH: Seven Hills Book Distributors,

1991.

Dudley, N. G is for EcoGarden: An A to Z Guide to a More Organically

Healthy Garden. New York: Avon, 1992.

Erickson, J. Gardening for a Greener Planet: A Chemical-Free Approach. Blue

Ridge Summit, PA: TAB Books, 1992.

National Research Council. Alternative Agriculture. Washington, DC: Na-

tional Academy Press, 1989.

Rodale, R. Regenerative Farming Systems. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press, 1985.

1036

P

ERIODICALS

Krueger, S. “Green Acres: Farmers Are Hoping Chemical-Free Crops Will

Help Get Them Out of the Red.” Nature Canada 21 (Spring 1992): 42–48.

Organic waste

Organic wastes contain materials which originated from liv-

ing organisms. There are many types of organic wastes and

they can be found in

municipal solid waste

, industrial

solid waste

, agricultural waste, and wastewaters. Organic

wastes are often disposed of with other wastes in landfills

or incinerators, but since they are

biodegradable

, some

organic wastes are suitable for

composting

and land appli-

cation.

Organic materials found in municipal solid waste in-

clude food, paper, wood, sewage

sludge

, and

yard waste

.

Because of recent shortages in

landfill

capacity, the number

of municipal composting sites for yard wastes is increasing

across the country, as is the number of citizens who compost

yard wastes in their backyards. On a more limited basis,

some mixed municipal waste composting is also taking place.

In these systems, attempts to remove inorganic materials are

made prior to composting.

Some of the organic materials in municipal solid waste

are separated before disposal for purposes other than com-

posting. For example, paper and cardboard are commonly

removed for

recycling

.

Food waste

from restaurants and

grocery stores is typically disposed of through

garbage

dis-

posals, therefore, it becomes a component of

wastewater

and sewage sludge.

A large percentage of sewage sludge is landfilled and

incinerated, but it is increasingly being applied to land as a

fertilizer

. Sewage sludge may be used as an agricultural

fertilizer or as an aid in reclaiming land devastated by

strip

mining

,

deforestation

, and over-application of inorganic

fertilizers. It may also be applied to land solely as a means

of disposal, without the intention of improving the

soil

.

The organic fraction of industrial waste covers a wide

spectrum including most of the components of municipal

organic waste, as well as countless other materials. A few

examples of industrial organic wastes are papermill sludge,

meat processing waste, brewery wastes, and textile mill fibers.

Since a large variety and volume of industrial organic wastes

are generated, there is a lot of potential to recycle and com-

post these materials. Waste managers are continually experi-

menting with different “recipes” for composting industrial

organic wastes into soil conditioners and soil amendments.

Some treated industrial wastewaters and sludges contain

large amounts of organic materials and they too can be used

as soil fertilizers and amendments.