Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean dumping

cluder devices (TEDs) on shrimp nets to help protect thou-

sands of endangered sea turtles. Turtles have also benefited

from the Ocean Conservatory’s research in artificial lighting.

The group convinced counties and cities throughout Florida

to control the use of artificial light on the state’s beaches

after proving that it prevents turtles from nesting and lures

baby turtles away from their natural habitat.

In 1988 the Ocean Conservatory established a database

on marine debris and, subsequently, the group created two

Marine Debris Information offices, one in Washington,

D.C. and one in San Francisco. These offices provide infor-

mation on marine debris, especially

plastics

, to scientists,

policy makers, teachers, students, and the general public.

While many of the Ocean Conservatory’s projects are exem-

plary, one has received so much attention that it has been

used as a model by other environmental groups, including the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA). The California

Marine Debris Action Plan, which went into effect in 1994,

is a comprehensive strategy for combating marine debris,

and a collaborative effort of the Ocean Conservatory and a

wide network of public and private organizations. In 2000

President Clinton enacted the Oceans Act which set up an

Oceans Commission to review and revise all policies dealing

with the protection of the ocean and the coast. The most

recent win for the Ocean Conservatory came in 2001, when

Tortugus (200 square nautical miles) was established as the

largest no-take marine reserve near Key West, Florida.

[Cathy M. Falk]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Ocean Conservancy, 1725 DeSales Street, Suite 600, Washington,

D.C. USA 20036 (202) 429-5609, Email: info@oceanconservancy.org,

<http://www.oceanconservancy.org>

Ocean dumping

Ocean dumping is internationally defined as “any deliberate

disposal at sea of wastes or other matter from vessels, aircraft,

platforms, or other man-made structures at sea, and any

deliberate disposal at sea of vessels, aircraft, platforms, or

other man-made structures at sea.” The

discharge

of sewage

and other effluents from a pipeline and the discharge of

waste incidental to, or derived from the normal operations

of, ships are not considered ocean dumping. Wastes have

been dumped into the ocean for thousands of years. Fish

and fish processing wastes, rubbish, industrial wastes, sewage

sludge

, dredged material,

radioactive waste

, pharmaceu-

tical wastes, drilling fluids, munitions,

coal

wastes, cryolite,

ocean

incineration

wastes, and wastes from ocean mining

have all been dumped at sea. Ocean dumping has historically

1007

been more economically attractive, when compared with

other land-based

waste management

options.

The 1972

Convention on the Prevention of Marine

Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter

, com-

monly called the London Convention, came into force in

1975 to control ocean dumping activities. The framework

of the London Convention includes a black list of materials

that may not be dumped at sea under any circumstances

(including radioactive and industrial wastes), a grey list of

materials considered less harmful that may be dumped after

a special permit is obtained, and criteria that countries must

consider before issuing an ocean dumping permit. These

criteria require the consideration of the effects dumping

activities can have on marine life, amenities, and other uses

of the ocean, and encompass factors related to disposal opera-

tions, waste characteristics, attributes of the site, and avail-

ability of land-based alternatives. Most ocean dumping per-

mits (90–85%) reported by parties to the London

Convention are for dredged material. Currently only three

parties to the London Convention dump sewage sludge at

sea. Other categories of wastes that are permitted for ocean

dumping include inert, geological materials, vessels, and fish

wastes. The International Maritime Organization is respon-

sible for administrative activities related to the London Con-

vention, and it facilitates cooperation among the countries

party to the Convention. As of 2001, 78 countries had rati-

fied the Convention.

In the early 1990s, the parties to the London Conven-

tion began a comprehensive review of the treaty. This re-

sulted in the adoption of the 1996 Protocol to the London

Convention. The purpose of the Protocol is similar to that

of the Convention, but the Protocol is more restrictive:

application of a “precautionary approach” is included as a

general obligation; a “reverse list” approach is adopted; incin-

eration of wastes at sea is prohibited; and export of wastes for

the purpose of dumping or incineration at sea is prohibited.

Under the reverse list approach, dumping is prohibited unless

explicitly permitted, and only seven categories of materials

may be considered for dumping: dredge material; sewage

sludge; fish waste; vessels and platforms; inert, inorganic

geological material; organic material of natural origin; and

bulky items of unharmful materials when produced at loca-

tions with no other disposal options. The Protocol will enter

into force after 26 states ratify it (15 of which are party to

the London Convention). So far, 16 countries have ratified

it (13 of which are party to the London Convention).

Ocean dumping has been used as a method for munici-

pal waste disposal in the United States for about 80 years,

and even longer for dredged material. The law to regulate

ocean dumping in the United States is the Marine Protec-

tion, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972. This Act, also

known as the Ocean Dumping Act, banned the disposal of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean dumping

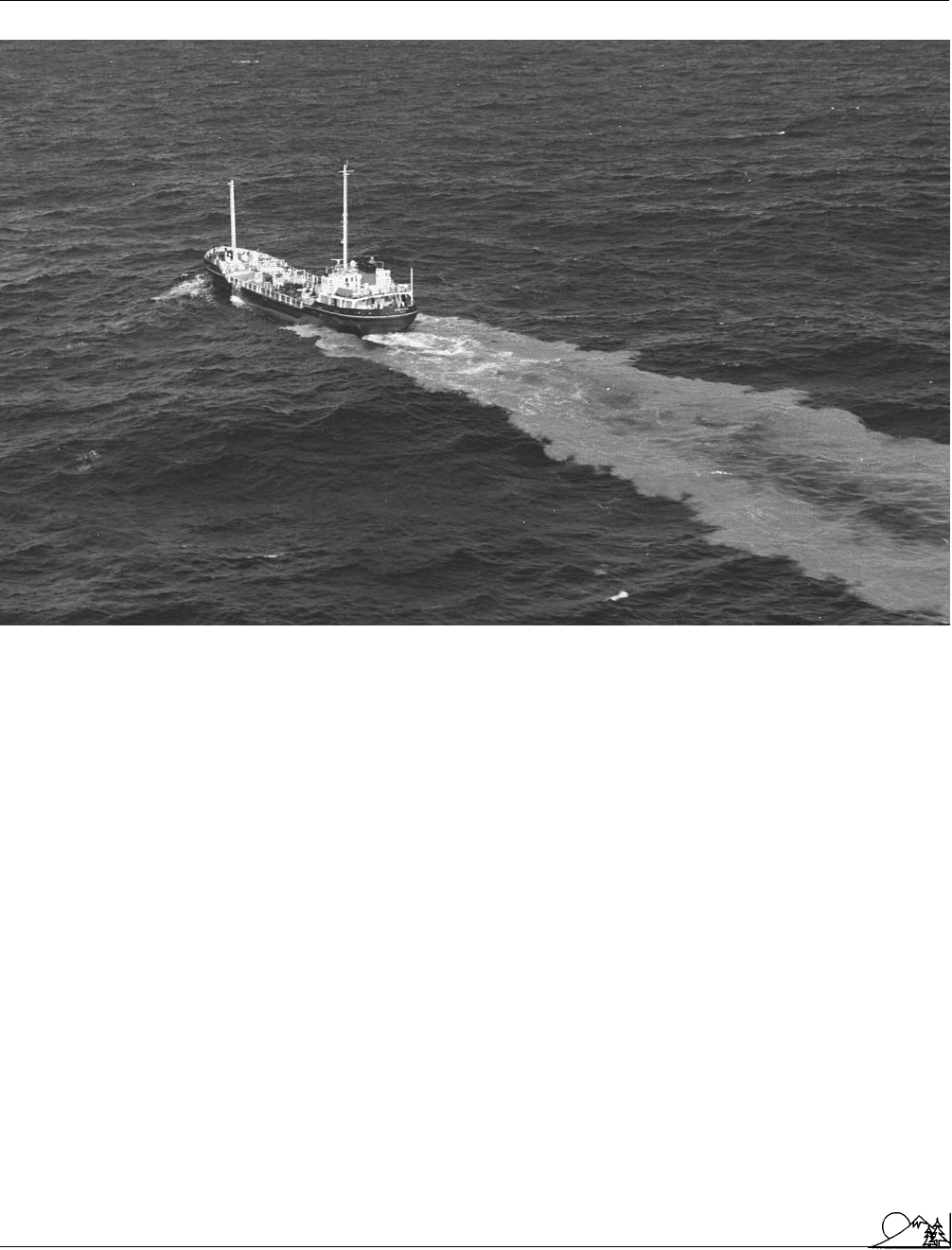

A ship dumping jarosite waste into the ocean off the Australia coast. (Photograph by Hewetson. Greenpeace. Reproduced

by permission.)

radiological, chemical, and biological warfare agents, high-

level radioactive waste, and medial waste. It requires a permit

for the ocean dumping of any other materials. Such a permit

can only be issued where it is determined that the dumping

will not unreasonably degrade or endanger human health,

welfare, or amenities, or the marine environment, ecological

systems, or economic potentialities. Furthermore, all permits

require notice and opportunity for public comment. EPA

was directed to establish criteria for reviewing and evaluating

ocean dumping permit applications that consider the effect

of, and need for, the dumping. The Ocean Dumping Act

has been revised by the United States Congress in the years

since its enactment. In 1974, Congress amended this Act

to conform with the London Convention. In 1977, the Act

was amended to incorporate a ban by 1982 on ocean dump-

ing of wastes that may unreasonably degrade the marine

environment

. As a result of this ban, approximately 150

permittees dumping sewage sludge and industrial waste

stopped ocean dumping of these materials. In 1983, the law

was amended to make any dumping of low-level radioactive

waste require specific approval by Congress. In 1988, the

1008

Ocean Dumping Ban Act

was passed to prohibit ocean

dumping of all sewage sludge and industrial waste by 1992.

Virtually all material ocean dumped in the United States

today is dredged material. Other materials include fish

wastes, human remains, and vessels.

Physical properties of wastes, such as density, and

its chemical composition affect the dispersal, and settling

of the wastes dumped at sea. Many contaminants such

as metals found in trace amounts in natural materials are

enriched in wastes. After material is dumped at sea, there

is usually initial, rapid dispersion of the waste. For example,

some wastes are dumped from a moving vessel, with

dilution rates of 1,000 to 100,000 from the ship’s wake.

As the wake subsides, naturally occurring turbulence and

currents further disperse wastes eventually to nondetectable

background levels in water in a matter of hours to days,

depending on the type of wastes and physical oceanic

processes. Dilution is greater if the material is released

slower and in smaller amounts, with dispersal rates decreas-

ing over time. Wastes, such as dredged material, that are

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean Dumping Ban Act (1988)

much denser than the surrounding seawater sink rapidly.

Less dense waste sinks more slowly, depending on the

type of waste and physical processes of the dumpsite. As

sinking waste particles reach seawater of equal density,

they begin to spread horizontally, with individual particles

slowly settling to the sea bottom. The accumulation of

the waste on the sea floor varies with the location and

characteristics of the dumpsite. Quiescent waters with little

tidal and wave action in enclosed shallow environments

have more waste accumulate on the bottom in the general

vicinity of the dumpsite. Wastes dumped in more open,

well-mixed ocean waters are transported away from the

dumpsite by currents and can disperse over a very large

area, as much as several hundred square kilometers.

The physical and chemical properties of wastes change

after the material has been dumped into the ocean. As wastes

mix with seawater, acid-base neutralization, dissolution or

precipitation of waste solids, particle

adsorption

and de-

sorption, volatilization at the sea surface, and changes in the

oxidation state may occur. For example, when acid-iron

waste is dumped at sea, the buffering capacity of seawater

rapidly neutralizes the waste. Hydrous iron oxide precipitates

are formed as the iron reacts with seawater and changes

from a dissolved to a solid form.

The fraction of the waste that settles to the bottom

is further changed as it undergoes geochemical and biological

processes. Some of the elements of the waste may be mobi-

lized in organic-rich

sediment

; however, if sulfide ions are

present, metals in waste may be immobilized by precipitation

of metal sulfides. Organisms living on the sea floor may

ingest waste particles, or mix waste deeper in the sediment by

burrowing activities.

Microorganisms

decompose

organic

waste

, potentially

recycling

elements from the waste before

it becomes part of the sea floor sediments. Generally sedi-

ment-related processes will act on waste particles over a

longer time scale than hydrologic processes in the water

column.

The effects of dumping on the ocean are difficult

to measure and depend on complex interactions of factors

including type, quantity, and physical and chemical proper-

ties of the wastes; method and rate of dumping; toxicity to

the

biotic community

; and numerous site-specific charac-

teristics, such as water depth, currents (turbulence), water

column density structure, and sediment type. Many studies

have found that the effects of ocean dumping on the water

column are usually temporary and that the ocean floor re-

ceives the most impact. Impacts from dumping dredged

material are usually limited to the dumpsite. Burial of some

benthic organisms (organisms living at or near the sea floor)

may occur; however, burrowing organisms may be able to

move vertically through the deposited material and fishes

typically leave the area. Seagrasses, coral reefs, and oyster

1009

beds may never recover after dredged material is dumped

on them. There also can be topographic changes to the sea

floor. See also Dredging

[Marci L. Bortman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

ArmyCorps of Engineers Ocean Disposal Database. [cited July 2002]. <http://

ered1.wes.army.mil/ODD>.

“EPA’s Ocean Dumping and Dredged Material Management.” EPA Web

Site. July 16, 2002 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/owow/oceans/

regulatory/dumpdredged/dumpdredged.html>.

London Convention. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.londonconventi-

on.org>.

Ocean dumping act

see

Marine Protection, Research and

Sanctuaries Act (1972)

Ocean Dumping Ban Act (1988)

The Ocean Dumping Ban Act of 1988 (Public Law 100-

688) marked an end to almost a century of sewage

sludge

and industrial waste dumping into the ocean. The law was

enacted amid negative publicity about beach closures from

high levels of pathogens and

floatable debris

washing up

along New York and New Jersey beaches and strong public

sentiment that ending ocean dumping may improve coastal

water quality

. The Ban Act prohibits sewage sludge and

industrial wastes from being dumped at sea after December

31, 1991. This law is an amendment to the Marine Protec-

tion, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (Public Law

92-532), which regulates the dumping of wastes into ocean

waters. These laws do not cover wastes that are discharged

from outfall pipes such as from

sewage treatment

plants

or industrial facilities or that are generated by vessels.

The Ocean Dumping Ban Act was not the first at-

tempt to prohibit dumping of sewage sludge and industrial

wastes at sea. An earlier ban was developed by the U. S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and later passed

by the U.S. Congress (Public Law 95-153) in 1977, amend-

ing the 1972 act. This 1977 law prohibits ocean dumping

that “may unreasonably degrade the marine environment”

by December 31, 1981. Approximately 150 entities dumping

sewage sludge and industrial waste sought alternative dis-

posal options. However, New York City, and eight munici-

palities in New York and New Jersey filed a lawsuit against

the EPA objecting to the order to end their ocean dumping

practices. A Federal district court granted judgment in their

favor, allowing them to continue ocean dumping under a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean farming

court order. The court held that the EPA must balance, on

a case-by-case basis, all relevant statutory criteria with the

economics of ocean dumping against land-based alternatives.

After 1981, the New York and New Jersey entities were the

only dumpers of sewage sludge, and there were only two

companies dumping industrial waste at sea.

In anticipation of the 1988 Ocean Dumping Ban Act,

one of the two industries stopped its dumping activities in

1987. The remaining industry, which was dumping hydro-

chloric

acid

waste, also ceased its activities before the 1988

Ban Act became law. The entities from New Jersey and

New York continued to dump a total of approximately eight

million wet metric tonnes of sewage sludge (half from New

York City) annually into the ocean.

From 1924 to 1987, sludge dumpers used a site approx-

imately 12 miles (19 km) off the coasts of New Jersey and

New York. The EPA, working with the

National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), determined

that ecological impacts such as shellfish bed closures, elevated

levels of metals in sediments, and introduction of human

pathogens into the marine

environment

were attributed

entirely or in part to sludge dumping at the 12 mile site. As

a result the EPA decided to phase out the use of this site

by December 31, 1987. The sewage sludge dumpers were

required to move their activities farther offshore to the 106-

mile (171-km) deep water dumpsite, located at the edge of

the continental shelf off southern New Jersey. Industries had

used this dumpsite from 1961 to 1987.

The Ocean Dumping Ban Act prohibits all dumping

of sewage sludge and industrial waste into the ocean, without

exception. The law also prohibits any new dumpers, and

required existing dumpers to obtain new permits that in-

cluded plans to phase-out sewage sludge dumping at sea.

The Ban Act also established ocean dumping fees and civil

fines for any dumpers that continue their activities after the

mandated end date. The fines were included in the law in

part because legislators assumed that some sludge dumpers

would not be able to meet the December 31, 1991 deadline.

The law required fees of $100 per dry ton of sewage sludge

or industrial waste in 1989, $150 per dry ton in 1990, and

$200 per dry ton in 1991. After the 1991 deadline penalties

rose to $600 per ton for any sludge dumped, and increased

incrementally in each subsequent year. Those ocean dumpers

that continue beyond December 31, 1991 are allowed to use

a portion of their penalties for developing and implementing

alternative sewage sludge management strategies. While the

amount of the penalty increased each year after 1991, the

amount that could be devoted to developing land-based

disposal alternatives decreased.

As part of the law, the EPA, in cooperation with

NOAA, is responsible for implementing an

environmental

monitoring

plan at the 12 mile site, the 106 mile site,

1010

and surrounding areas potentially influenced by dumping

activities to determine the effects of dumping on living ma-

rine resources. The Ban Act also includes provisions not

directly associated with dumping of sewage sludge or indus-

trial waste at sea. Massachusetts Bay-MA, Barataria Terreb-

onne Estuary Complex-LA, Indian River Lagoon-FL, and

Peconic Bay-NY were named as priority areas for consider-

ation to the

National Estuary Program

by EPA. The law

also includes a prohibition on the disposal of

medical waste

at sea by public vessels. Finally, the Ban Act requires vessels

transporting

solid waste

over the New York Harbor to the

Staten Island

Landfill

to use nets to secure the waste to

minimize the amount that may spill overboard.

The New Jersey dumpers ceased ocean dumping by

March 1991. The two New York counties stopped ocean

dumping by December 1991 and New York City, the last

entity to dump sewage sludge into the ocean, stopped zn

June 1992. Landfilling is currently used as an alternative

to ocean dumping and other sewage sludge management

strategies are under consideration including

incineration

(after the sludge is dewatered),

composting

, land applica-

tion, and pelletization. See also Convention on the Prevention

of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Waste and Other

Matter

[Marci L. Bortman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Kitsos, T. R., and J. M. Bondareff. “Congress and Waste Disposal at Sea.”

Oceanus 33 (Summer 1990): 23–28.

Millemann, B. “Wretched Refuse Off Our Shores.” Sierra 74 (January-

February 1989): 26–28.

“Ocean Dumping Ban Advances.” Journal of the Water Pollution Control

Federation 60 (August 1988): 1320+.

Weis, J. S. “Ocean Dumping Revisited.” BioScience 38 (December 1988):

749.

Ocean farming

Although oceans cover about 70% of the Earth’s surface,

most food is produced on land areas through agriculture

and animal husbandry. This is because 90% of the ocean is

unproductive. The productive areas are near shore, such as

continental shelfs,

upwellings

, coral reefs, mangrove

swamps (also known as mangal communities), and estuaries.

The primary reason why these near shore areas are more

productive than the open ocean is because of the supply of

nutrients which are needed for plant (primarily

phytoplank-

ton

) productivity, which fuels the

food chain/web

.

A worldwide plateau in harvesting of natural fish catch

was reached in about 1989, so commercial and sport fisheries

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean farming

in the oceans cannot be increased unless something is

changed. One possibility is to enhance production through

fertilization of the water. Another, more practical, possibility

is through

aquaculture

. As wild harvests decrease and per

capita seafood consumption increases, aquaculture should

have an important role. For example, the U.S. imports 60%

of its seafood, which contributes to its trade imbalance.

Aquaculture can help by providing jobs as well as food prod-

ucts for domestic consumption and for export.

Aquaculture done in seawater is known as

maricul-

ture

. Fish and shellfish are grown in improved conditions

to produce more and better food in environments with lower

predation and disease. There are several forms of aquacul-

ture: intensive, extensive, and open ocean. In extensive aqua-

culture, relatively little control is exerted by the mariculturist.

These typically occur near shore where organisms are grown

in several different ways: floating cages or pens; cordoned-

off bodies of water which can be fertilized for enhanced

production; or racks and other structures (to grow shellfish).

For example, oyster farmers in the

Chesapeake Bay

place

clean substrates in selected areas of the bottom mud each

summer to collect young oyster larvae (called “spat") as they

settle down from the

plankton

. These young oysters attach

and grow on the substrates, which are periodically transferred

to new locations to prevent them from being covered with

mud and

silt

. After several years, the oysters are large enough

to be marketed. Other culture methods for bivalves such as

oysters and clams utilize the stake method, which involves

the use of bamboo or other poles driven into the

sediment

and placed approximately 6 ft (2 m) apart. Nylon ropes

hanging from floats can also be used to collect larvae. Follow-

ing growout, the shellfish are collected and sold on the

market. Farmers in the Philippines are able to produce nearly

1.5 tons per acre (0.60 tons per ha) of mussels and 1.7

tons per acre (0.70 tons per ha) of oysters annually. These

techniques all have relatively low cost and maintenance.

Sometimes there are problems with

pollution

from domestic

and industrial waste, and periodic blooms of toxic dinoflagel-

lates (a type of phytoplankton), which create red tides. Red

tides can be unhealthy and even lethal to humans.

Intensive mariculture systems involve the production

of large quantities of marine animals in relatively small areas.

They are relatively expensive to build and maintain, so typi-

cally only highly-valued

species

are used, such as lobsters,

shrimp, halibut, and certain other fish. Intensive systems

can sometimes be located in tanks on land, using either

pumped salt water from the nearby ocean or recirculated

artificial seawater if the system is located farther away from

the ocean. Typically, however, nearshore or offshore floating

tanks or pens are used. The organisms are raised from eggs

to market size in these controlled environments.

Salmon

have been raised in sea pens (netted cages) for over 20 years

1011

along the Pacific coast of the United States and Canada

and along the Atlantic coasts of France, Scotland, and the

Scandinavian countries, especially Norway. This process typ-

ically involves the growth of salmon from fertilized eggs

through the fry stage in indoor fresh water hatcheries. This

is followed by the transfer of parr (the stage after the fry in

which the fish develop vertical lines along their sides) to

outdoor tanks or cages in salt water. The fish are fed either

commercial pellets or “trash” fish such as herring, capelin,

menhaden, and anchovies. The feeding process can be quite

labor-intensive, and thus translates into one of the highest

expenses for the salmon farmer. After one to two years, the

salmon go through a process called smoltification, which

involves a physiological change that allows them to live in

salt water. The smolt are then transferred to salt water cages

for another one to two years until they reach a market size

of about 4-12 lb (2-5 kg). Rainbow and sea trouts are handled

in a similar way, although they are usually larger when moved

into sea pens. As with the extensive method, problems can

arise through pollution and red tides.

Most mariculture industries use both nearshore and

offshore cages for raising the fish. The nearshore cages are

necessary for raising young fish, but the offshore cages are

better for raising fish to maturity because of enhanced grow-

ing conditions (cleaner water and lower

mortality

). Im-

provements are still needed, such as methods to remove dead

fish, make grading (sorting) of fish possible, make harvesting

easier and feeding possible (particularly during adverse

weather), and make fouling removal easier. It will also be

helpful to construct 24-hour living accommodations on some

of the larger offshore units.

A third form of mariculture is known as ocean ranch-

ing, or “enhancement aquaculture.” This can be compared

to cattle ranching on land. For example, salmon are raised

in hatcheries until they reach the smolt stage, and are then

released at a particular point along the shore where they

swim away until they reach reproductive maturity. Like other

anadromous fish, they return to that same area several years

later, where they are recaptured, processed, and sold on the

market. Salmon are ideal fish for this because they are “self-

herding.” However, normal returns range from only 1-20%,

depending upon the

water quality

of the return

environ-

ment

and the release size of the fish. For example, Coho

salmon fry that were around 0.5 oz (14 g) showed a 1-2%

return while those twice this size had a 7-8% return rate.

Recent research has shown that released salmon can be im-

printed to return to salt water sites, which has the added

advantages of lower cost (due to not needing more expensive

property located along streams that enter the ocean), and

better meat quality (which declines when salmon swim from

salt to fresh water). The Sea Run, Inc. salmon company of

Kennebunkport, Maine, rears Pacific pink and chum salmon

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean outfalls

from eggs to fingerlings in a hatchery located near the

dis-

charge

of an oil-fired power plant. The water has a charac-

teristic temperature and smell which attracts the salmon

back to the same area each year. They have also experimented

with the release of morpholine and phenyethyl alcohol (syn-

thetic organic compounds) to the water to aid in imprinting.

Similar ocean ranching techniques have been used in

other countries. For example, in Japan the natural catch of

Red Sea bream has declined for the last 24 years (more than

a 51% decrease) due to over-exploitation, so these fish have

been raised in tanks and cages since 1962. Other species

commonly raised in Japan include salmon, flounder, mack-

erel, bluefin tuna, shrimp, scallops, and abalone. Many of

these species have a high consumer demand and thus are

highly priced. Abalone can also be grown to a small size of

approximately 1 in (3 cm) and used to re-seed areas where

the natural population has declined. They can then be har-

vested as adults about three to five years later. However,

recapture rates are typically low (only 0.5–10%).

Ocean farming or ranching is becoming popular

worldwide. In Equador, Mazatlan Yellowtail fish are grown

to commercial size (2.7 lb; 1.2 kg) in six months with a 90%

survival rate. Other species raised in this country include

flounder, snook, red drum, and Pacific pompano. In

Austra-

lia

, oysters are commonly raised via sea ranching. Scallops

and salmon are now raised in Canada. Mussels, oysters,

clams, bream, turbot, and salmon are common mariculture

species in Spain, where the warm water allows these species

to be grown to market size in a shorter time.

Recent work has been done on algal turf mariculture

around some Caribbean islands in natural, unfertilized wa-

ters. Test plots have shown that they can raise up to 25

million tons (23 million metric tonnes) of dry algae per year

without harming the natural

ecosystem

. This product can

then be used for direct human ingestion or as food to raise

marine invertebrates (such as West Indian spider crabs,

conchs, and whelks) as well as some herbivorous fish. This

would be particularly helpful because conch are now an

endangered species

through over-harvesting in this area.

Ocean ranching, along with other forms of aquacul-

ture, is an exciting field that should be in greater demand

in the future. Our progeny may depend on it more for global

food production to feed the increasing human population.

[John Korstad]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Landau, M. Introduction to Aquaculture. New York: Wiley, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Adey, W. H. “Food Production in Low-Nutrient Seas.” BioScience 37

(1987): 340–8.

1012

Shelty, H. P. C., and G. P. Satyanarayana Rao. “Aquaculture in India.”

World Aquaculture 27 (1996): 20–24.

O

THER

Reinertsen, H., L.A. Dahle, L. Jørgensen, and K. Tvinnereim. Fish Farming

Technology. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Fish Farm-

ing Technology, Trondheim, Norway, August 9-12, 1993. Brookfield, VT:

Balkema Publishers, 1993.

Ocean outfalls

Pipelines extending into coastal and ocean waters that are

used by various industries and municipal

wastewater

treat-

ment facilities to

discharge

treated

effluent

. Some may be

simple pipes serving as conveyances from land-based facili-

ties; others include diffusers that help to rapidly dilute efflu-

ent or risers that ensure effluent is discharged at a certain

height above the ocean floor. The conveyances may extend

more than three miles (5 km) offshore, beyond coastal waters

into open ocean. Offshore oil and gas exploration, develop-

ment, and production rigs also possess ocean outfalls. Dis-

charges from these pipes must be permitted under the

Clean

Water Act national pollutant discharge elimination sys-

tem

. See also Sewage treatment

Ocean pollution

see

Marine pollution; Ocean dumping

Ocean thermal energy conversion

For many years, scientists have been aware of one enormous

reservoir

of energy on the earth’s surface: the oceans. As

sunlight falls on the oceans, its energy is absorbed by seawa-

ter. The oceans are in one sense, therefore, a huge “storage

tank” for

solar energy

. The practical problem is finding a

way to extract that energy and make it available for hu-

man use.

The mechanism suggested for capturing heat stored

in the ocean depends on a thermal gradient always present

in seawater. Upper levels of the ocean may be as much as

36°F (20°C) warmer than regions 0.6 mile (1 km) deeper.

The technology of ocean thermal energy conversion

(OTEC) takes advantage of this temperature gradient.

An OTEC plant would consist of a very large floating

platform with pipes at least 100 feet (30 m) in diameter

reaching to a depth of up to 0.6 mile (1 km). The “working

fluid” in such a plant would be ammonia, propane, or some

other liquid with a low boiling point.

Warm surface waters would be pumped into upper lev-

els of the plant, causing the working fluid to evaporate. As

the fluid evaporates, it will also exert increased pressure. That

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ocean thermal energy conversion

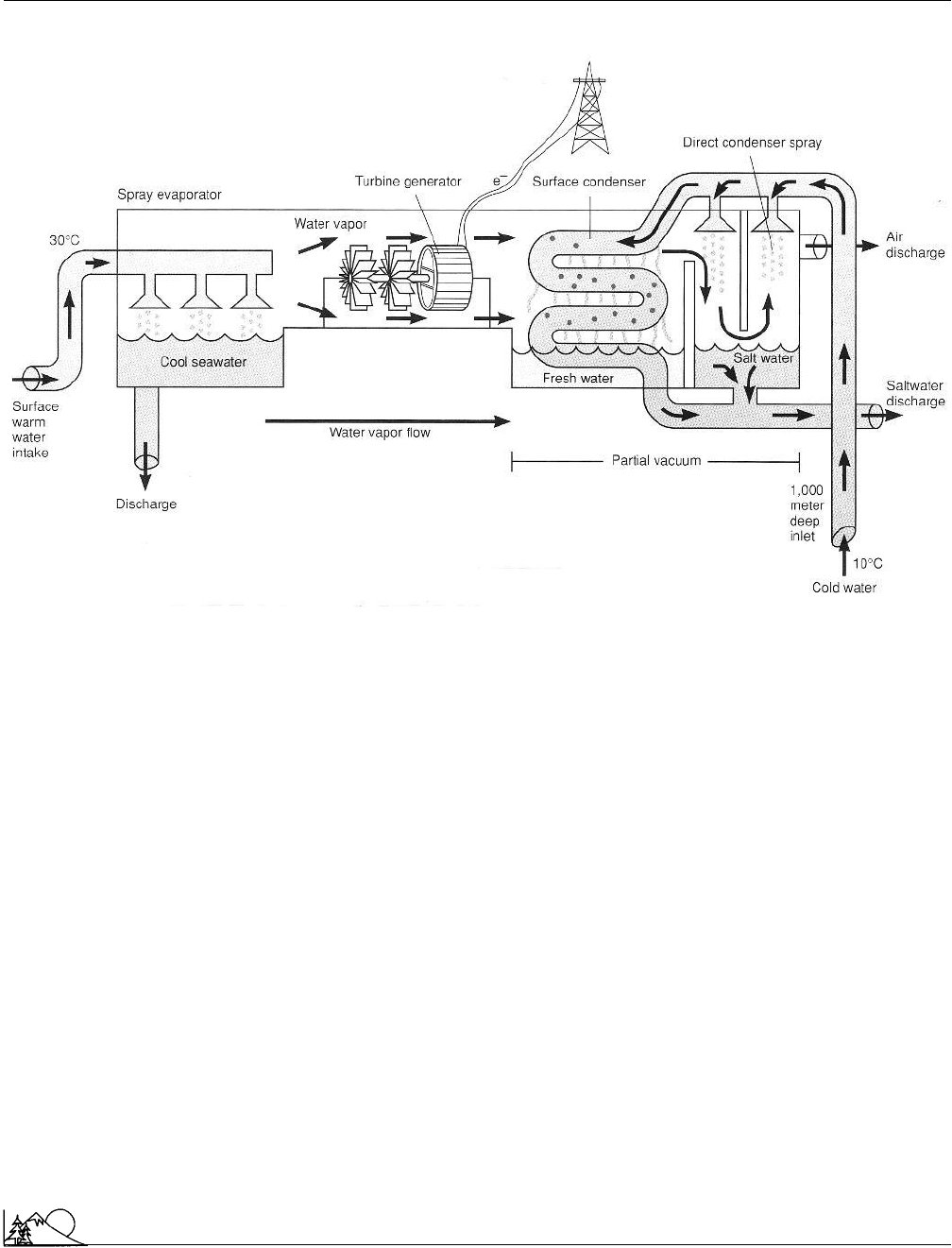

The Open Cycle Ocean Thermal Electric Generator requires a water temperature differential of at least 36°F

(20° C) to produce both fresh water and electricity. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

pressure can be used to drive a turbine that, in turn, generates

electricity. The electricity could be carried to shore along large

cables or used directly on the OTEC plant to desalinize water,

electrolyze water, or produce other chemical changes.

In the second stage of operation, cold water from deeper

levels of the ocean would be brought to the surface and used

to cool the working fluid. Once liquified, the working fluid

would be ready for a second turn of the generating cycle.

OTEC plants are attractive alterative energy sources

in regions near the equator, where surface temperatures may

reach 77°F (25°C) or more. These parts of the ocean are

often adjacent to

less developed countries

, where energy

needs are growing.

Wherever they are located, OTEC plants have a num-

ber of advantages. For one thing, oceans cover nearly 70

percent of the planet’s surface so that the raw material OTEC

plants need—seawater—is readily available. The original en-

ergy source—sunlight—is also plentiful and free. Such plants

are also environmentally attractive since they produce no

pollution

and cause no disruption of land resources. Planners

suggest that a by-product of OTEC plants might be nutri-

1013

ents brought up from deeper ocean levels and used to feed

“farms” of fish or shellfish.

Unfortunately, many disadvantages exist also. The

most important is the enormous cost of building and main-

taining the mammoth structures needed for an OTEC plant.

Also, the temperature differential available under even the

best of conditions means that an OTEC plant will not be

more than about 3% efficient.

Currently, the disadvantages of OTEC plants are so

great that none has even been built. Research continues in

a number of countries, but some experts believe that the low

efficiency of OTEC means that this technology will never

be able to compete economically with other alternative

sources of energy. See also Desalinization; Energy efficiency;

Power plant; Thermal stratification (water)

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Fisher, A. “Energy from the Sea.” Popular Science (June 1975): 78–83.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Octane rating

Haggin, J. “Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Experiment Slated for

Hawaii.” Chemical & Engineering News (February 10, 1986): 24–26.

Penney, T. R., and D. Bharathan, “Power from the Sea.” Scientific American

256 (January 1987): 86–92.

Walters, S. “Power in the Year 2001, Part 2—Thermal Sea Power.” Mechan-

ical Engineering (October 1971): 21–25.

Whitmore, W. “OTEC: Electricity from the Ocean.” Technology Review

(October 1978): 58–63.

OCRWM

see

Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste

Management

Octane rating

Octane rating is a method for describing antiknock proper-

ties of

gasoline

. Knocking is a pinging sound produced by

internal

combustion

engines when fuel ignites prematurely

during the engine’s compression cycle. Because knocking

can damage an engine and rob it of power, gasoline formula-

tions have been developed to minimize the problem. Gaso-

lines containing relatively large amounts of straight-chain

hydrocarbons

(such as n-heptane) have an increased ten-

dency to knock, whereas those containing branched-chain

forms (such as isooctane) burn more smoothly. In addition

to isooctane, other compounds also reduce engine knocking.

By using an index called octane number, it is possible to

compare the antiknock properties of gasoline mixtures. A

higher octane number indicates that a mixture has the equiv-

alent antiknock properties of a gasoline containing a higher

percentage of isooctane.

Although gasoline used as automotive fuel is now “de-

leaded,” gasoline used as aviation fuel still contains

tetra-

ethyl lead

as an octane enhancer and antiknock agent.

Svante Ode

´

n

Swedish agricultural scientist

One of the great environmental issues of the 1970s and

1980s was the problem of

acid

precipitation. Research stud-

ies suggested that rain, snow, and other forms of precipita-

tion in certain parts of the world had become increasingly

acidic over the preceding century. The southern parts of

Scandinavia and England, the Northeastern United States,

and Eastern Canada were four regions in which the phenom-

enon was particularly noticeable.

Evidence began to accumulate that the increasing level

of acidity might be associated with environmental damage,

such as the death of trees and aquatic life. Scientists began

to ask how extensive this damage might be and what sources

of acid precipitation could be identified.

1014

If any single person could be credited with raising

international awareness of this problem, it would probably

be the Swedish agricultural scientist Svante Ode

´

n. Ode

´

n

was certainly not the first person to recognize the existence,

effects, or origins of acid precipitation. That honor belongs

to an English chemist,

Robert Angus Smith

. As early as

1852, Smith hypothesized a connection between

air pollu-

tion

in Manchester and the high acidity of rains falling in

the area. He first used the term

acid rain

in a book he

published in 1872.

Smith’s research held relatively little interest to most

scientists, however. Those who did study acid rain ap-

proached their work with little concern about the

environ-

ment

and did so, as one of them later said, “with no environ-

mental consciousness,” but simply because “it was an

interesting situation.”

Ode

´

n’s attitude was quite different. He had been asked

by the Swedish government to prepare a report on his hy-

pothesis that acid rain falling on Swedish land and lakes

had its origins hundreds or thousands of miles away. In

preparing his report, he came to the conclusion that acid

rain might be responsible for widespread

fish kills

then

being reported by Swedish fishermen. Ode

´

n was shocked

by this discovery because, as he later said, it was the “first

real indication that acid precipitation had an impact on the

biosystem.”

Ode

´

n’s method of dealing with his discoveries was

unorthodox. In most cases, a researcher sends the report of

his or her work to a scientific journal, which has the report

reviewed by other scientists in the same field. If the research

is judged to have been well done, the report is published.

In this instance, however, Ode

´

n sent his report to a

Stockholm newspaper, Dagens Nyheter, where it was pub-

lished on October 24, 1967. Ode

´

n’s decision undoubtedly

disturbed some scientists, but it did have the effect of bring-

ing the issue of acid rain to the attention of the general

public.

A year later, Ode

´

n published a more formal report of

his research, “The

Acidification

of Air and Precipitation,

and Its Consequences,” in the Ecology Committee Bulletin.

The article was later translated into English. Ode

´

n carried

his message about acid precipitation to the United States in

person in 1971, when he presented a series of 14 lectures

on the topic at various institutions across the country. In his

presentations, he argued that acid rain was an international

phenomenon that, in Europe, originated especially in En-

gland and Germany and was spreading over thousands of

miles to other parts of the continent, especially Scandinavia.

His work also laid the foundation for Sweden’s case study

for the

United Nations Conference on the Human Envi-

ronment

“Air

Pollution

Across National Boundaries” pre-

sented at Stockholm in 1972. He further suggested that a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Eugene P. Odum

number of environmental effects, such as the death of trees

and fish and damage to buildings, could be traced to acid

precipitation. Ode

´

n’s passionate commitment to publicizing

his findings about acid precipitation was certainly a critical

factor in awakening the world’s awareness to the potential

problems of this environmental danger.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Boyle, R. H., and R. A. Boyle. Acid Rain. New York: Nick Lyons

Books, 1983.

Luoma, J. Troubled Skies, Troubled Waters. New York: Viking Press, 1984.

Park, C. Acid Rain: Rhetoric and Reality. London: Methuen, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

Cowling, E. B. “Acid Precipitation in Historical Perspective.” Environmen-

tal Science and Technology 16 (1982): 110A–123A.

Odor control

Refuse-handlers and many industries release unpleasant

odors into the air which can travel for miles. Odors inside

factories can also make it difficult for people to work, and

pollutants can impart a strong odor to water.

Odors can be released from

chemicals

, chemical reac-

tions, fires, or rotting material. The air carries odor-produc-

ing gas molecules, and they are detected by breathing or

sniffing. The molecules stimulate receptor cells in the nose,

which in turn send nerve impulses to the brain where they

are processed into information about the odor.

Research is being performed to quantify and character-

ize odors. Tests such as sniff

chromatography

,

emission

rate measurement, and hedonics are being used in an effort

to develop a better definition of what offensive odors are.

Scientists have found that the perception of odors is

highly subjective. What one person might not like, another

person might not be able to smell at all, and what people

define as an offensive odor depends on age and sex, as well

as other characteristics.

One method of controlling unpleasant smells is de-

odorizers. Deodorizers either disguise offensive odors with

an agreeable smell or destroy them. Some deodorizers do

this by chemically changing odor-producing particles while

others merely remove them from the air. Disinfectants, such

as formaldehyde, can kill bacteria,

fungi

or molds that create

odors. Odors can also be removed through ventilation sys-

tems. The air can be “scrubbed” by forcing it through liquid

or through

filters

containing such materials as charcoal,

methods which trap and remove odor-producing particles

from the air. Factories can also employ a process known as

1015

“re-odorization,” which works on the principle that there are

seven basic odor types: camphoraceous, mint, floral, musky,

ethereal, putrid, and pungent. The process is based on the

theory that different combinations of these odor types pro-

duce different smells, and re-odorization releases chemicals

into the air to combine with the regular factory odors and

generate a more pleasant smell.

Aeration

is one method of removing objectionable

odors from water. The surface of the water is mixed with

air and the oxygen oxidizes various materials that would

otherwise turn the water foul. Aeration can be accomplished

by running the water over steps or spraying the water through

nozzles. Trickling the water over trays of coke also helps

eliminate offensive odors, and adding activated charcoal can

have the same effect.

Even though science has shown that the perception

of odors is subjective, many people are offended by them.

It is often considered a quality-of-life issue, and politicians

have been strongly influenced by their constituencies. Nui-

sance regulations have been passed in many states and mu-

nicipalities, and though they often vary, their attempts to

distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable odors are

often vague and difficult to apply. Proving that odors inter-

fere with the quality of life is not only subjective but nearly

impossible. Refuse-handlers and factories are perhaps the

most adversely affected; they often receive heavy fines for

odors, although there is no proven method for eliminating

them. Many believe a more concrete system of regulations

is needed, but science has not been able to provide the basis

on which to build one. See also Noise pollution; Pollution

control

[Nikola Vrtis]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bowker, P. G. Odor and Corrosion Control in Sanitary Sewerage Systems and

Treatment Plants. New York: Hemisphere, 1989.

Hesketh, H. E. Odor Control Including Hazardous-Toxic Odors. Lancaster,

PA: Technomic, 1988.

Kreis, R. D. Control of Animal Production Odors: The State-of-the-Art. Ada,

OK: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1978.

P

ERIODICALS

Hunt, P., and K. Hauck. “Raising a Stink Over Composting Odors.”

American City and County 105 (December 1990): 64–65.

Dr. Eugene P. Odum (1913 – )

American ecologist

Eugene P. Odum has been called “the ecologist’s ecologist,”

meaning that he has been of special significance to his col-

leagues in the development of the discipline, and in formulat-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management

ing its content, outlines, and boundaries. He helped lay the

foundations for what might be called the “modern” study of

ecology

in the 1940s and 1950s by redirecting the field to

studies based on energetics, on the relatively new

ecosystem

concept, and on functional as well as structural analyses of

living communities. From early in his career, he has worked

to define general principles in ecology. His colleagues and

associates have recognized him by electing him president of

the

Ecological Society of America

, through election to the

National Academy of Sciences

, and through the awarding

of prestigious prizes, including the Tyler Award in 1977 and

the Crafoord Prize in 1987.

Odum was born in Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire,

to an academic family. His father, Howard W. Odum, was

a well-known sociologist, remembered today especially for

his work on regionalism. His brother, Howard T. Odum,

is a well-known systems ecologist. Eugene Odum received

his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology from the Uni-

versity of North Carolina, and his Ph.D. in ecology and

ornithology from the University of Illinois in 1939. He spent

brief stints as an instructor at Western Reserve University

and as a research biologist at the Edmund Niles Huck Pre-

serve in New York. In 1940, he accepted a teaching position

at the University of Georgia, spent the next four decades

there, and since his retirement in 1984, has been an emeritus

professor. During his tenure in Georgia, the university has

become a world center for the study of ecology, through

various departments but also through the Institute of Ecol-

ogy, which he helped initiate and of which he was the long-

time director.

Odum’s best-known work is his “landmark” general

text, Fundamentals of Ecology, first published in 1953, with

a third edition published in 1971. This text dominated the

market for two decades and is still a book to consult, includ-

ing an extensive and still useful reference list. Odum revised

the third edition “in light of the increasing importance of

the subject in human affairs.” That edition is organized

into three parts: basic ecological principles and concepts,

emphasizing energy and ecosystems; “the

habitat

approach,”

which discusses freshwater, marine, estuarine, and terrestrial

ecology; and applications and technology, which includes

chapters on resources,

pollution

and

environmental

health

, radiation ecology, remote sensing, and microbial

ecology. Since Odum is a well-known radiation ecologist,

that chapter especially is still timely.

Odum’s early work was on birds, an interest threaded

into his publications for many years. His research focused

for several years on various aspects of radiation ecology. He

turned early to an emphasis on energetics and on ecosystem

studies, becoming almost as well known for systems ecology

as his younger brother. A lot of his work has been on produc-

tivity in estuaries and marshes. And he is known for his

1016

work on old fields in the southern United States. That

research has, in many instances, been applied to problems

in environmental management, and to issues of human im-

pact and reciprocity.

In recent years, a considerable amount of his energy

has been devoted to human interactions with and impacts

on environmental systems. That last interest has turned

Odum into something of a philosopher, resulting in the

publication of several papers on values and ethics. One influ-

ence of his thinking that will be debated for a long time is

his repeated attempts to outline ecology as an integrative

discipline, and to locate ecologists as scientists interested in

every level of integration, from micro to macro. That work

has led him several times, with mixed success, to move away

from the classical reductionist approach in science and to

try an outline for a

holistic approach

in ecology.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Odum, E. P. Ecology: A Bridge Between Science and Society. Sunderland,

MA: Sinauer Associates, 1996.

———. Fundamentals of Ecology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders

Company, 1971.

P

ERIODICALS

Odum, E. P. “The Emergence of Ecology as a New Integrative Discipline.”

Science 195, no. 4284 (March 25, 1977).

———. “Great Ideas in Ecology for the 1990s.” BioScience 42, no. 7 (July

1992): 542–545.

Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste

Management

Humans have been using nuclear materials for nearly 50

years. Nuclear reactors and

nuclear weapons

account for

the largest volume of these materials, while industrial, medi-

cal, and research applications account for smaller volumes.

One of the largest single problems involved with the use of

nuclear materials is the volume of wastes resulting from

these applications. By one estimate, 8,000–9,000 metric tons

(8,816–9,918 tons) of high-level radioactive wastes alone are

produced in the United States every year. It is something

of a surprise, therefore, to learn that as late as 1982, the

United States had no plan for disposing of the radioactive

wastes produced by its commercial, industrial, research, and

defense operations.

In that year, the United States Congress passed the

Nuclear Waste Policy Act establishing national policy for

the disposal of

radioactive waste

. Responsibility for the

implementation of this policy was assigned to the

U.S. De-

partment of Energy

through the Office of Civilian

Radio-