Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN)

Permaculture emphasizes reactive homes, sheltered

from cold winds with windbreak planting. Such homes are

oriented on an east-west axis facing the sun, usually with a

greenhouse, and are well-sealed. They should use few re-

sources not found on site. Shelters can be built into the

earth, with living turf roofs. Sometimes, living trees and

plants are used to create shelters.

Permaculture offers an

environmental design

prac-

tice for making better use of resources in a variety of growing

settings. What started as a method for cultivating

desert

land has grown into a system that integrates living systems,

fostering greater consciousness of ecosystems and helping

to ensure economic and ecological sustainability for its prac-

titioners. Contact: Permaculture Resources, 56 Farmersville

Rd., Califon, N.J. 07830; phone: 800-832-6285.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Barnes, L. “The Permaculture Connections.” In Southeastern Permaculture

Network News.

Mollison, B. Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, Permaculture One and Per-

maculture Two. Australia: Tagari, 1979.

Permafrost

Permafrost is any ground, either of rock or

soil

, which is

perennially frozen. Continuous permafrost refers to areas

which have a continuous layer of permafrost. Discontinuous

permafrost occurs in patches. It is believed that continuous

permafrost covers approximately 4% of the earth’s surface

and can be as deep as 3,281 ft (1,000 m), though normally

it is much less. Permafrost tends to occur when the mean

annual air temperature is less than the freezing point of

water. Permafrost regions are characterized by a seasonal

thawing and freezing of a surface layer known as the active

layer which is typically 3–10 ft (1–3 m) thick.

Permanent retrievable storage

Permanent retrievable storage is a method for handling

highly toxic hazardous wastes on a long-term basis. At one

time, it was widely believed that the best way of dealing

with such wastes was to seal them in containers and either

bury them underground or dump them into the oceans.

However, these containers tended to leak, releasing these

highly dangerous materials into the

environment

.

The current method is to store such wastes in a quasi-

permanent manner in salt domes, rock caverns, or secure

buildings. This is done in the expectation that scientists will

1067

eventually find effective and efficient methods for converting

these wastes into less hazardous states, in which they can

then be disposed of by conventional means. One chemical

for which permanent retrievable storage has been used so

far is the group of compounds known as polychlorinated

biphenyl (PCB)s.

Permanent retrievable storage has its disadvantages.

Hazardous wastes so stored must be continuously guarded

and monitored in order to detect breaks in containers or

leakage into the surrounding environment. In comparison

with other disposal methods now available for highly toxic

materials, however, permanent retrievable storage is still the

preferred alternative means of disposal. See also Hazardous

waste site remediation; Hazardous waste siting; NIMBY;

Toxic use reduction legislation

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Makhijani, A. High-Level Dollars, Low-Level Sense: A Critique of Present

Policy for the Management of Long-Lived Radioactive Wastes and Discussion

of an Alternative Approach. New York: Apex Press, 1992.

Schumacher, A. A Guide to Hazardous Materials Management. New York:

Quorum Books, 1988.

P

ERIODICALS

Flynn, J., et al. “Time to Rethink Nuclear Waste Storage.” Issues in Science

and Technology 8 (Summer 1992): 42–46.

Kliewer, G. “The 10,000-Year Warning.” The Futurist 26 (September-

October 1992): 17–19.

Permeable

In

soil

science, permeable is a qualitative description for the

ease with which water or some other fluid can pass through

soil. Permeability in this context is a function not only of

the total pore volume but also of the size and distribution

of the pores. In geology, particularly with reference to

groundwater

, permeability is the ability of water to move

through any water-bearing formation, rock, or unconsoli-

dated material. This condition can be measured in the labo-

ratory by measuring the volume of water that flows through

a sample over a certain period of time. See also Aquifer;

Recharge zone; Soil profile; Vadose zone; Zone of saturation

Peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN)

The best known member of a class of photochemical oxidiz-

ing agents known as the peroxyacyl

nitrates

. The peroxyacyl

nitrates are formed when

ozone

reacts with

hydrocarbons

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Persian Gulf War

such as those found in unburned

petroleum

. They are com-

monly found in

photochemical smog

. The peroyxacyl ni-

trates attack plants, causing spotting and discoloration of

leaves, destruction of flowers, reduction in fruit production

and seed formation, and death of the plant. They also cause

red, itchy, runny eyes and irritated throats in humans. Car-

diac and respiratory conditions, such as

emphysema

and

chronic

bronchitis

, may result from long-term exposure to

the peroxyacyl nitrates. See also Air pollution; Los Angeles

Basin

Persian Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War in 1991 had a variety of environmental

consequences for the Middle East. The most devastating of

these effects were from the

oil spills

and oil fires deliberately

committed by the Iraqi army. There were extensive press

coverage of these events at the time, and the United States

accused the Iraqis of “environmental terrorism.” These accu-

sations were seen by some as propaganda effort, and there

was almost certainly some political motivation to both how

the damage was estimated and how it was characterized

during the war. But it is clear now that the note of outrage

often struck by the Allies was not out of place. The devasta-

tion, though not as extensive as originally supposed, was still

substantial.

The Iraqis began discharging oil into the Persian Gulf

from the Sea Island Terminal and other supertanker termi-

nals off the coast of Kuwait on January 23, 1991. Allied

bombers tried to limit the damage by striking at pipelines

carrying oil to these locations, but the flow continued

throughout the war. Estimates of the size of the spill have

varied widely and the controversy still continues, with a

number of diplomatic and political pressures preventing

many government agencies from committing themselves to

specific figures. But it now seems likely that this was the

worst oil spill in history, probably 20 times larger than the

Exxon Valdez

spill in

Prince William Sound

, Alaska, and

twice the size of the 1979 spill from the blowout of Ixtoc I

well in the Gulf of Mexico.

Whatever the actual size of the spill, it occurred in an

area that was already one of the most polluted in the world.

Oil spills and oil dumping are common in the Persian Gulf;

it has been estimated that as many as two million barrels of

oil are spilled in these waters every year. Some ecologists

believe that the

ecosystem

in the area has a certain amount

of

resistance

to the effects of

pollution

. Other scientists

have maintained that the high level of

salinity

in the Gulf

will prevent the oil from having many long-term effects and

that the warm water will increase the speed at which the oil

1068

Two men cleaning a bird soaked in oil that was

spilled into the Persian Gulf by Iraq during the

Persian Gulf War. (Photograph by Wesley Bocxe, Na-

tional Audubon Society Collection. Photo Researchers Inc.

Reproduced by permission.)

degrades. But the Gulf has a slow circulation system and

large areas are very shallow; many scientists and environmen-

talists have predicted that it will be many years before the

water can clear itself.

The spill killed thousands of birds within months after

it began, and it had an immediate and drastic effect on

commercial fishing

in the region. Oil soaked miles of coast-

line; coral reefs and

wetlands

were damaged, and the sea-

grass beds of the Gulf were considered particularly vulnera-

ble. Mangrove swamps, migrant birds, and

endangered

species

such as green turtles and the dugong, or sea cow,

are still threatened by the effects of the spill. The Saudi

Arabian government has protected the water they draw from

the Gulf for

desalinization

, but little has been done to

limit or alleviate the environmental damage. This has been

the result, at least in part, of a shortage of resources during

and after the war, as well as obstacles such as floating mines

and shallow waters which restricted access for boats carrying

cleanup equipment.

At the end of the war, the retreating Iraqi army

set over 600 Kuwaiti oil

wells

on fire. When the last

burning well was extinguished on November 6, 1991, these

fires had been spewing oil

smoke

into the

atmosphere

for

months, creating a cloud which spread over the countries

around the Gulf and into parts of Asia. It was thought

at the time that the cloud of oil smoke would rise high

enough to cause global climatic changes. Carl Sagan and

other scientists, who had first proposed the possibility of

a

nuclear winter

as one of the consequences of a nuclear

war, believed that rain patterns in Asia and parts of

Europe would be affected by the oil fires, and they

predicted failed harvests and widespread starvation as a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Persistent compound

result. Though there was some localized cooling in the

Middle East, these kinds of global predictions did not

occur, but the smoke from the fire has still been an

environmental disaster for the region.

Air quality

levels

have caused extensive health problems, and

acid rain

and

acid deposition

have damaged millions of acres of forests

in Iran.

The oil fires and oil spills were not the only environ-

mental consequences of the Persian Gulf War. The move-

ment of troops and military machinery, especially tanks,

damaged the fragile

desert

soils and increased wind

erosion

.

Wells sabotaged by the Iraqis released large amounts of oil

that was never ignited, and lakes of oil as large as half a

mile wide formed in the desert. These lakes continue to

pose a hazard for animals and birds, and tests have shown

that the oil is seeping deeper into the ground, causing long-

term contamination and perhaps, eventually,

leaching

into

the Gulf. See also Gulf War syndrome

[Douglas Smith]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Peck, L. “The Spoils of War.” The Amicus Journal 3 (Spring 1991): 6–9.

Zimmer, C. “Ecowar.” Discover 13 (January 1992): 37–39.

Persistent compound

A persistent compound is slow to degrade in the

environ-

ment

, which often results in its accumulation and deleterious

effects on human and

environmental health

if the com-

pound is toxic. Toxic metals such as

lead

and

cadmium

,

organochlorides such as

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs), and

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

(PAHs)

are persistent compounds.

Persistent molecules are termed recalcitrant if they fail

to degrade, metabolize, or mineralize at significant rates.

Their compounds can be transported through the environ-

ment over long periods of time and over long distances,

resulting in long-term exposure and possible changes in

organisms and ecosystems. However, organisms and ecosys-

tems may adapt to the compounds, and deleterious effects

may weaken or even disappear.

Compounds may be persistent for several reasons. A

compound can be persistent due to its chemical structure.

For example, in a molecule, the number and arrangement

of

chlorine

ions or hydroxyl groups can make a compound

recalcitrant. It can also persist due to unfavorable environ-

mental conditions such as

pH

, temperature, ionic strength,

1069

potential for

oxidation reduction reactions

, unavailability

of nutrients, and absence of organisms that can degrade the

compound.

The period of persistence can be expressed as the time

required for half of the compound to be lost, the

half-life

.

It is also often expressed as the time for detectable levels of

the compound to disappear entirely. Compounds are classi-

fied for environmental persistence in the following catego-

ries:(1) Not degradable, compound half-life of several centu-

ries; (2) Strong persistence, compound half-life of several

years; (3) Medium persistence, compound half-life of several

months; and (4) Low persistence, compound half-life less

than several months.

Non-degradable compounds include metals and many

radioisotopes, while semi-degradable compounds (of me-

dium to strong persistence) include PAHs and chlorinated

compounds. Compounds with low persistence include most

organic compounds based on

nitrogen

, sulfur, and

phos-

phorus

.

In general, the greater the persistence of a compound,

the more it will accumulate in the environment and the

food chain/web

. Non-degradable and strongly persistent

compounds will accumulate in the environment and/or

organisms. For example, because of

bioaccumulation

through the food chain, dieldrin can reduce populations of

birds of prey. Compounds with intermediate persistence

may or may not accumulate, while non-persistent pollutants

generally do not accumulate. However, even compounds

with low persistence can have long-term deleterious effects

on the environment.

2,4-D

and

2,4,5-T

can cause

defolia-

tion

, which may result in

soil erosion

and long-term effects

on the

ecosystem

.

Chemical properties of a compound can be used to

assess persistence in the environment. Important properties

include: (1) rate of biodegradation (both

aerobic

and

anaer-

obic

); (2) rate of hydrolysis; (3) rate of oxidation or reduction;

and (4) rate of photolysis in air, soil, and water. In addition,

the effects of key parameters, such as temperature, concen-

tration, and pH, on the rate constants and the identity and

persistence of transformation products should also be investi-

gated. However, measured values for these properties for

many persistent compounds are not available, since there

are thousands of

chemicals

, and the time and resources

required to measure the desired properties for all the chemi-

cals is unrealistic. In addition, the data that are available are

often of variable quality.

Persistence of a compound in the environment is de-

pendent on many interacting environmental and compound-

specific factors, which makes understanding the causes of

persistence of a specific compound complex and in many

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Persistent organic pollutants

cases incomplete. See also Chronic effects; Heavy metals and

heavy metal poisoning; Toxic substance

[Judith Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ayres, R. U., F. C. McMichael, and S. R. Rod. “Measuring Toxic Chemicals

in the Environment: A Materials Balance Approach.” In Toxic Chemicals,

Health, and the Environment, edited by L. B. Lave and A. C. Upton.

Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Govers, H., J. H. F. Hegeman, and H. Aiking. “Long-Term Environmental

and Health Effects of PMPs.” In Persistent Pollutants: Economics and Policy,

edited by H. Opschoor and D. Pearce. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer

Academic Publishers, 1991.

Lyman, W. J. “Estimation of Physical Properties.” In Environmental Expo-

sure from Chemicals. Vol. 1. Edited by W. B. Neely and G. E. Blau. Boca

Raton: CRC Press, 1985.

Persistent organic pollutants

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are man-made organic

compounds that persist in the natural

environment

for long

periods of time. Because of their long-lasting presence in

air, water, and

soil

, they accumulate in the bodies of fish,

animals, and humans over time. Exposure to POPs can

create serious health disorders throughout the tiers of the

food web. In human beings, POPs can cause

cancer

, auto-

immune deficiencies, kidney disorders,

birth defects

, and

other reproductive problems.

Because these

chemicals

are derived from manufac-

turing industries,

pesticide

applications, waste disposal sites,

spills, and

combustion

processes, POPs are a global prob-

lem. Many POPs are carried long distances through the

atmosphere

. They tend to move from warmer climates to

colder ones, which is why even remote regions such as the

Arctic contain significant levels of these contaminants. Be-

cause of the global creation and transmission of POPs, no

country can protect itself against POPs without assistance.

An international commitment is essential for eradication of

this problem.

In the early 1990s the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD),

United Nations

Environment Programme

(UNEP), World Health Orga-

nization (WHO), and other groups began to assess the im-

pacts of hundreds of chemicals, including POPs. In 1998

36 countries participated in the POPs Protocol, sponsored

by the

Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air

Pollution

. The purpose was to build an international effort

toward controlling POPs in the environment.

In 2001, led by the UNEP, over 100 countries partici-

pated in the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic

Pollutants. The proposal will become a legally binding

1070

agreement upon its ratification by 50 or more countries.

It is considered by many to be a landmark human-health

document of international proportions. Research will address

the most effective ways to reduce or eliminate POP produc-

tion, various import/export issues, disposal procedures, and

the development of safe, effective, alternative chemical com-

pounds.

The screening criteria for POP designation are: the

potential for long-range atmospheric transport, persistence

in the environment, bioaccumlation in the tissues of living

organisms, and toxicity. Many chemicals volatilize, which

increases the concentrations of these chemicals in the air.

Longevity is measured by a chemical’s

half-life

, or how

much time passes before half of the original amount of a

chemical

discharge

or

emission

breaks down naturally and

dissipates from the environment. The minimum half-life for

a POP in water is two months; for soil or

sediment

it is

about six months. Several POPs have half-lives as long as

12 years. Animals accumulate POPs in their fatty tissue

(

bioaccumulation

); these POPs are then consumed and

reconcentrated by higher-order animals in the food chain

(

biomagnification

). In some

species

, biomagnification can

result in concentrations up to one million times greater than

the background value of the POP. Most humans are exposed

through consumption of food products (especially meat, fish,

and dairy products) that contain small amounts of these

chemicals.

The Stockholm Convention calls for the immediate

ban on production and use of 12 POPs (known as the

“dirty dozen"): aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, DDT,

chlordane

,

heptachlor,

mirex

,

toxaphene

, hexachlorobenzene (HCB),

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs), polychlorinated diox-

ins, and

furans

. The convention did acknowledge, however,

certain health-related use exemptions until effective, envi-

ronmentally friendly substitutes can be found. For example,

DDT can still be applied to control malarial mosquitoes

subject to WHO guidelines. Electrical transformers that

contain PCBs can also be used until 2025, at which point

any old transformers that are still active must be replaced

with PCB-free equipment.

A brief description of the 12 banned POPs is shown

below:

O

Aldrin was a commonly used pesticide for the control of

termites, corn rootworm, grasshoppers, and other insects.

It has been proven to cause serious health problems in

birds, fish, and humans. Aldrin biodegrades in the natural

environment to form dieldrin, another POP

O

Dieldrin was applied extensively to control insects, espe-

cially termites. Its half-life in soil is about five years. Diel-

drin is especially toxic to birds and fish.

O

Endrin, another insecticide, is used to control insects

and certain rodent populations. It can be metabolized in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Persistent organic pollutants

animals, however, which reduces the risk of bioaccumula-

tion. It has a half-life of about 12 years.

O

DDT, also known as dichlorodiphenyl trichloroethane, was

applied during World War II to protect soldiers against

insect-borne diseases. In the 1960s and 1970s its use on

crops resulted in dramatic decreases in bird populations,

including the

bald eagle

. DDT is still being manufactured

today and is a chemical intermediate in the manufacture

of dicofol. Regions that want to continue using DDT for

public-health purposes include Africa, China, and India

(mosquitoes, however, are becoming resistant to DDT in

these areas).

O

Chlordane is a broad-spectrum insecticide used in termite

control. Its half-life is about one year. Chlordane is easily

transported through the air and suspected of causing im-

mune system problems in humans.

O

Heptachlor was applied to control

fire ants

, termites, and

mosquitoes and has been used in closed industrial electrical

junction boxes. Its production has been eliminated in most

countries.

O

Mirex was used as an insecticide to control fire ants and

termites. It is also a fire-retardant component in

rubber

,

plastics

, and electrical goods. It is a very stable POP with

a half-life of up to 10 years.

O

Toxaphene is an insecticide that was widely used in the

United States in the 1970s to protect cereal grains, cotton

crops, and vegetables. Toxaphene has a half-life of 12 years.

Aquatic life is especially vulnerable to toxaphene toxicity.

O

Hexachlorobenzene, also called HCB, was introduced in

the 1940s to treat seeds and kill

fungi

that damaged crops.

It can also be produced as a by-product of chemical manu-

facturing. It is suspected of causing reproductive problems

in humans.

O

Polychlorinated biphenyls, commonly referred to as PCBs,

were used extensively in the electrical industry as a heat

exchange fluid in transformers and capacitors. They were

also used as an additive in plastics and paints. PCBs are

no longer produced but are still in use in many existing

electrical systems. Thirteen varieties of PCBs create dioxin-

like toxicity. Studies have shown PCBs are responsible for

immune system suppression, developmental neurotoxicity,

and reproductive problems.

O

Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, usually shortened to

the term “dioxins,” are chemical by-products of incomplete

combustion or chemical manufacturing. Common sources

of dioxins are municipal and

medical waste

incinerators,

backyard burning of trash, and past emissions from elemen-

tal

chlorine

bleach pulp and paper manufacturing. A diox-

in’s half-life is typically 10–12 years. Related health prob-

lems can include birth defects, reproductive problems,

immune and

enzyme

disorders, and increased cancer risk.

1071

O

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans, usually shortened to “fu-

rans” or “PCDFs,” are structurally similar to dioxins and

by-products of the same processes as for dioxins. The health

impacts of dibenzofuran toxicity are considered to be simi-

lar to those of dioxins. Over 135 types of PCDFs are

known to exist.

The UNEP and other world organizations are contin-

uing to look for safer and more economically viable alterna-

tives to POPs. Manufacturing facilities are being upgraded

with cleaner technologies that will reduce or eliminate emis-

sions. Focus is also being placed on regulating the interna-

tional trade of hazardous substances. Disposal is also an

issue; poorer countries don’t have the money or proper tech-

nological resources to dispose of the growing accumulations

of obsolete toxic chemicals. The UNEP is working creatively

with countries to secure financing to introduce alternative

products, technology, methods enforcement, and critical in-

frastructure. Research sponsored by UNEP studies the

chemical characteristics of current POPs so that chemical

companies will be less likely to create new POPs.

The Convention on Long-range Transboundary

Air

Pollution

has been extended by eight protocols, including

the 1998 protocol on POPs. The third meeting of an ad-

hoc group of experts on POPs was held in 2002. These

scientists continue to research other chemicals that may qual-

ify in the future as POPs.

Current technical review activities focus on the follow-

ing chemicals:

O

Ugilec, which was used in capacitors, transformers, and as

a hydraulic fluid in underground mining. It was originally

thought to be a safe replacement for PCBs.

O

Hexachlorobutadiene (HCBD) was used to recover chlo-

rine-bearing gas from chlorine plants. It is very toxic to

aquatic life. HCBD is on national priority lists for some

countries, such as Canada.

O

Pentabromodiphenyl ether (PentaBDE) is sold as a bromi-

nated flame retardant. Its use has doubled in the last 10–

15 years. This compound volatilizes easily and enters the

air long after the disposal of treated products.

O

Pentachlorobenzene (PeCB) was used as a

fungicide

,

flame retardant, and as a component in dielectric fluids.

Although it is no longer being produced, there is still an

abundance of PeCB in the environment. It is probably

released through

landfill

leaching/degassing or inciner-

ation.

O

Polychlorinated naphthalenes (PCNs) are structurally sim-

ilar to PCBs. In the 1980s PCNs were a component of

products called Halowax, Nibren Wax, and Seekay Wax.

Uses included wood preservation, electroplating, dye carri-

ers, and wire insulation. Major points of release are old

electrical equipment or incineration.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pest

O

Short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCP) are still being

used today in the rubber, leather, and metal-working indus-

tries, especially in China. No suitable substitutes have been

developed yet.

O

Polychlorinated terphenyls (PCTs) are very similar in

structure and chemical behavior to PCBs. Over 8,000 dif-

ferent varieties of PCTs theoretically exist. PCTs have not

been commercially produced since the 1980s, but are still

part of aging electrical capacitors and transformers.

[Mark J. Crawford]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

Draft Summaries for Discussion by the Expert Group on POPs, Protocol on

POPs. Summary documents. United Nations Economic Commission for

Europe, Environmental and Human Settlements Division, June 2002.

The Foundation for Global Action on Persistent Organic Pollutants: A United

States Perspective. External review draft. U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency, November 2001.

New Protocol on Persistent Organic Pollutants Negotiated. News release. U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pesticide Programs, 1998.

Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Global Issue, a Global Response. Brochure.

Document EPA 160-F-02-001. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,

Office of Internal Affairs, 2002.

Stockholm Convention on POPs. Pamphlet. United Nations Environment

Programme, June 2001

O

RGANIZATIONS

United Nations Environment Programme, Chemicals Division, 11-13

chemin des Anemones, 1219 Chatelaine, Geneva, Switzerland (41) (22)

917-8191, Fax: (41) (22) 797-3460

U.S Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW,

Washington, DC USA 20460 (202)260-2090

Pest

A pest is any organism that humans consider destructive or

unwanted. Whether or not an organism is considered a pest

can vary with time, geographical location, and individual

attitude. For example, some people like pigeons, while others

regard them as pests. Some pests are merely an inconve-

nience. In the United States, mosquitoes are thought of as

pests because they are an annoyance, not because they are

dangerous. The most dangerous pests are those that carry

disease or destroy crops. One direct way of controlling pests

is by

poisoning

them with toxic

chemicals

(pesticides). A

more environmentally sensitive approach is to find natural

predators that can be used against them (biological controls).

See also Bacillus thuringiensis; Integrated pest management;

Population biology

1072

Pesticide

Pesticides are

chemicals

that are used to kill insects, weeds,

and other organisms to protect humans, crops, and livestock.

There have been many substantial benefits of the use of

pesticides. The most important of these have been: (1) an

increased production of food and fibre because of the protec-

tion of crop plants from pathogens,

competition

from

weeds,

defoliation

by insects, and parasitism by nematodes;

(2) the prevention of spoilage of harvested, stored foods;

and (3) the prevention of debilitating illnesses and the saving

of human lives by the control of certain diseases.

Unfortunately, the considerable benefits of the use of

pesticides are partly offset by some serious environmental

damages. There have been rare but spectacular incidents of

toxicity to humans, as occurred in 1984 at

Bhopal, India

,

where more than 2,800 people were killed and more than

20,000 seriously injured by a large

emission

of poisonous

methyl isocyanate vapor, a chemical used in the production

of an agricultural insecticide.

A more pervasive problem is the widespread environ-

mental contamination by persistent pesticides, including the

presence of chemical residues in

wildlife

, in well water,

in produce, and even in humans. Ecological damages have

included the

poisoning

of wildlife and the disruption of

ecological processes such as productivity and

nutrient

cy-

cling. Many of the worst cases of environmental damage

were associated with the use of relatively persistent chemicals

such as DDT. Most modern pesticide use involves less-

persistent chemicals.

Pesticides can be classified according to their intended

pest

target:

O

fungicides protect crop plants and animals from fungal

pathogens;

O

herbicides kill weedy plants, decreasing the competition

for desired crop plants;

O

insecticides kill insect defoliators and vectors of deadly

human diseases such as

malaria

, yellow fever,

plague

,

and typhus;

O

acaricides kill mites, which are pests in agriculture, and

ticks, which can carry encephalitis of humans and domestic

animals;

O

molluscicides destroy snails and slugs, which can be pests of

agriculture or, in waterbodies, the vector of human diseases

such as schistosomiasis;

O

nematicides kill nematodes, which can be

parasites

of the

roots of crop plants;

O

rodenticides control rats, mice, gophers, and other rodent

pests of human habitation and agriculture;

O

avicides kill birds, which can depredate agricultural fields;

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pesticide

O

antibiotics treat bacterial infections of humans and domes-

tic animals.

The most important use-categories of pesticides are

in human health, agriculture, and forestry:

Human Health

In various parts of the world,

species

of insects and

ticks play a critical role as vectors in the transmission of

disease-causing pathogens of humans. The most important

of these diseases and their vectors are: (1) malaria, caused

by the protozoan Plasmodium and spread to humans by an

Anopheles-mosquito vector; (2) yellow fever and related viral

diseases such as encephalitis, also spread by mosquitoes; (3)

trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness, caused by the protozo-

ans Trypanosoma spp. and spread by the tsetse fly Glossina

spp.; (4) plague or black death, caused by the bacterium

Pasteurella pestis and transmitted to people by the flea Xenop-

sylla cheops, a parasite of rats; and (5) typhoid fever, caused

by the bacterium Rickettsia prowazeki and transmitted to

humans by the body louse Pediculus humanus.

The incidence of all of these diseases can be reduced

by the judicious use of pesticides to control the abundance

of their vectors. For example, there are many cases where

the local abundance of mosquito vectors has been reduced

by the application of insecticide to their aquatic breeding

habitat

, or by the application of a persistent insecticide to

walls and ceilings of houses, which serve as a resting place

for these insects. The use of insecticides to reduce the abun-

dance of the mosquito vectors of malaria has been especially

successful, although in many areas this disease is now re-

emerging because of the

evolution

of tolerance by mosqui-

toes to insecticides.

Agriculture

Modern, technological agriculture employs pesticides

for the control of weeds, arthropods, and plant diseases, all

of which cause large losses of crops. In agriculture, arthropod

pests are regarded as competitors with humans for a common

food resource. Sometimes, defoliation can result in a total

loss of the economically harvestable agricultural yield, as in

the case of acute infestations of locusts. More commonly,

defoliation causes a reduction in crop yields. In some cases,

insects may cause only trivial damage in terms of the quantity

of

biomass

that they consume, but by causing cosmetic

damage they can greatly reduce the economic value of the

crop. For example, codling moth (Carpocapsa pomonella) lar-

vae do not consume much of the apple that they infest, but

they cause great esthetic damage by their presence and can

render produce unsalable.

In agriculture, weeds are considered to be any plants

that interfere with the productivity of crop plants by compet-

ing for light, water, and nutrients. To reduce the effects of

weeds on agricultural productivity, fields may be sprayed

with a

herbicide

that is toxic to the weeds but not to the

1073

crop plant. Because there are several herbicides that are toxic

to dicotyledonous weeds but not to members of the grass

family, fields of maize, wheat, barley, rice, and other grass-

crops are often treated with those herbicides to reduce weed

populations.

There are also many diseases of agricultural plants that

can be controlled by the use of pesticides. Examples of

important fungal diseases of crop plants that can be managed

with appropriate fungicides include: (1) late blight of potato,

(2) apple scab, and (3) Pythium-caused seed-rot, damping-

off, and root-rot of many agricultural species.

Forestry

In forestry, the most important uses of pesticides are

for the control of defoliation by epidemic insects and the

reduction of weeds. If left uncontrolled, these pest problems

could result in large decreases in the yield of merchantable

timber. In the case of some insect infestations, particularly

spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) and

gypsy

moth

(Lymantria dispar), repeated defoliation can cause the

death of trees over a large area of forest. Most herbicide use

in forestry is for the release of desired conifer species from

the effects of competition with angiosperm herbs and shrubs.

In most places, the quantity of pesticide used in forestry is

much smaller than that used in agriculture.

Pesticides can also be classified according to their simi-

larity of chemical structure. The most important of these are:

O

Inorganic pesticides, including compounds of

arsenic

,

copper

,

lead

, and

mercury

. Some prominent inorganic

pesticides include Bordeaux mixture, a complex pesticide

with several copper-based active ingredients, used as a

fun-

gicide

for fruit and vegetable crops; and various arsenicals

used as non-selective herbicides and

soil

sterilants and

sometimes as insecticides.

O

Organic pesticides, which are a chemically diverse group

of chemicals. Some are produced naturally by certain plants,

but the great majority of organic pesticides have been syn-

thesized by chemists. Some prominent classes of organic

pesticides are:

O

Biological pesticides are bacteria,

fungi

, or viruses that are

toxic to pests. One of the most widely used biological

insecticide is a preparation manufactured from spores of

the bacterium

Bacillus thuringiensis

, or B.t. Because this

insecticide has a relatively specific activity against leaf-

eating lepidopteran pests and a few other insects such as

blackflies and mosquitoes, its non-target effects are small.

The intended ecological effect of a pesticide applica-

tion is to control a pest species, usually by reducing its

abundance to an economically acceptable level. In a few

situations, this objective can be attained without important

non-target damage. However, whenever a pesticide is broad-

cast-sprayed over a field or forest, a wide variety of on-site,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pesticide Action Network

non-target organisms are affected. In addition, some of the

sprayed pesticide invariably drifts away from the intended

site of deposition, and it deposits onto non-target organisms

and ecosystems. The ecological importance of any damage

caused to non-target, pesticide-sensitive organisms partly

depends on their role in maintaining the integrity of their

ecosystem

. From human perspective, however, the impor-

tance of a non-target pesticide effect is also influenced by

specific economic and esthetic considerations.

Some of the best known examples of ecological damage

caused by pesticide use concern effects of DDT and other

chlorinated hydrocarbons

on predatory birds, marine

mammals, and other wildlife. These chemicals accumulate

to large concentrations in predatory birds, affecting their

reproduction and sometimes killing adults. There have been

high-profile, local and/or regional collapses of populations of

peregrine falcon

(Falco peregrinus),

bald eagle

(Haliaeetus

leucocephalus), and other raptors, along with

brown pelican

(Pelecanus occidentalis), western grebe (Aechmorphorus occiden-

talis), and other waterbirds. It was the detrimental effects

on birds and other wildlife, coupled with the discovery of a

pervasive presence of various chlorinated

hydrocarbons

in

human tissues, that led to the banning of DDT in most

industrialized countries in the early 1970s. These same

chemicals are, however, still manufactured and used in some

tropical countries.

Some of the pesticides that replaced DDT and its

relatives also cause damage to wildlife. For example, the

commonly used agricultural insecticide carbofuran has killed

thousands of waterfowl and other birds that feed in treated

fields. Similarly, broadcast-spraying of the insecticides phos-

phamidon and fenitrothion to kill spruce budworm in in-

fested forests in New Brunswick, Canada, has killed untold

numbers of birds of many species.

These and other environmental effects of pesticide

use are highly regrettable consequences of the broadcast-

spraying of these toxic chemicals in order to cope with pest

management problems. So far, similarly effective alternatives

to most uses of pesticides have not been discovered, although

this is a vigorously active field of research. Researchers are

in the process of discovering pest-specific methods of control

that cause little non-target damage and in developing meth-

ods of

integrated pest management

. So far, however, not

all pest problems can be dealt with in these ways, and there

will be continued reliance on pesticides to prevent human

and domestic-animal diseases and to protect agricultural and

forestry crops from weeds, diseases, and depredations caused

by economically important pests. See also Agent Orange;

Agricultural chemicals; Agricultural pollution; Algicide;

Chlordane; Cholinesterase inhibitor; Diazinon; Environ-

mental health; Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenti-

cide Act (1947); Kepone; Methylmercury seed dressings;

1074

National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides; Organ-

ochloride; Persistent compound; Pesticide Action Network;

Pesticide residue; 2,4-D; 2,4,5-T

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Baker, S., and C. Wilkinson, eds. The Effect of Pesticides on Human Health.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton Scientific Publishing, 1990.

Freedman, B. Environmental Ecology. 2nd edition, San Diego: Academic

Press, 1995.

Hayes, W. J., and E. R. Laws, eds. Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology. San

Diego: Academic Press, 1991.

McEwen, F. L., and G. R. Stephenson. The Use and Significance of Pesticides

in the Environment. New York: Wiley, 1979.

Pesticide Action Network

The

Pesticide

Action Network is an international coalition

of more than 300 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)

that works to stop both pesticide misuse and the proliferation

of pesticide use worldwide. The Pesticide Action Network

North America Regional Center (PANNA) is the North

American member.

The Pesticide Action Network serves as a clearing-

house to disseminate information to pesticide action groups

and individuals in this country and abroad. It promotes

research on and implementation of alternatives to pesticide

use in agriculture, such as

integrated pest management

programs. With a library of 6,000 books, reports, articles,

slides, and other materials, it sponsors a pesticide issues

referral and information service.

Formerly called the Pesticide Education Action Proj-

ect, which was founded in 1982, PANNA conducts the

Dirty Dozen Campaign to “replace the most notorious pesti-

cides with sustainable, ecologically sound alternatives.” Vari-

ous materials published by PANNA include brochures, pam-

phlets and books on United States pesticide problems and

on global pesticide use. It publishes a quarterly newsletter,

Global Pesticide Campaigner, and a bimonthly publication,

PANNA Outlook.

The organization also publishes a number of books

dealing with pesticides and

pest

control including Problem

Pesticides, Pesticide Problems: A Citizen’s Action Guide to the

UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) International

Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides; FAO

Code: Missing Ingredients; and Breaking the Pesticide Habit:

Alternatives to 12 Hazardous Pesticides. While PANNA is

not a membership organization for individuals outside of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pesticide residue

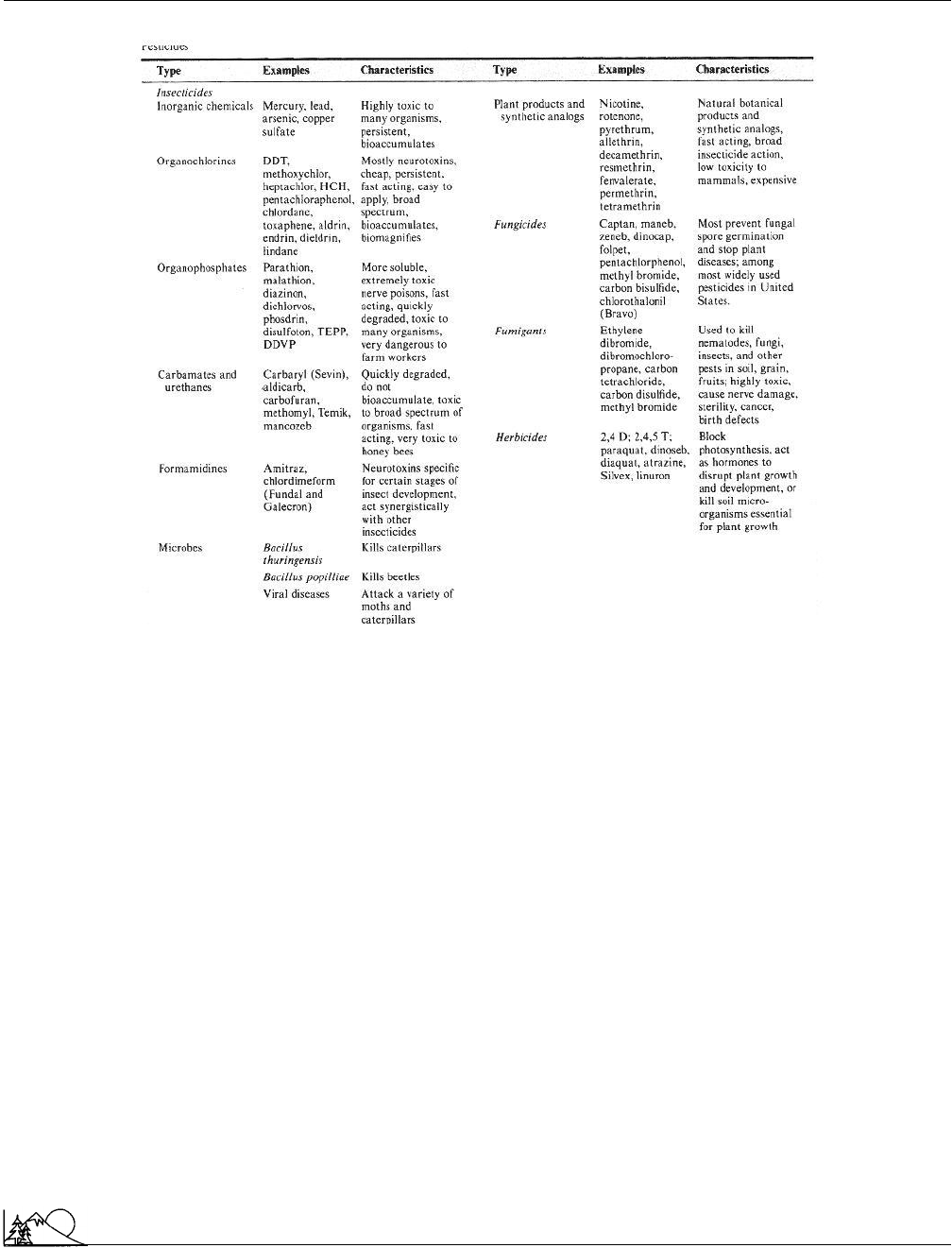

Different types of pesticides. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

the member NGOs, it does offer subscriptions to its quarterly

newsletter.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Pesticide Action Network North America, 49 Powell St., Suite 500, San

Francisco , CA USA 94102 (415) 981-1771 , Fax: (415) 981-1991 , Email:

panna@panna.org, <http://www.panna.org>

Pesticide residue

Chemical substances—pesticides and herbicides—that are

used as weed and insect control on crops and animal feed

always leave some kind of residue either on the surface or

within the crop itself after treatment. The amounts of residue

vary, but they do remain on the crop when ready for harvest

and consumption.

While these

chemicals

are generally registered for use

on food crops, it does not necessarily mean they are “safe.”

As part of its program to regulate the use of pesticides,

1075

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) sets “tolerances”

which are the maximum amount of pesticides that may

remain in or on food and animal feed. Tolerances are set at

levels that are supposed to ensure that the public (including

infants and children) is protected from unreasonable health

risks posed by eating foods that have been treated.

Tolerances are initially calculated by measuring the

amount of

pesticide

that remains in or on a crop after it is

treated with the pesticide at the proposed maximum allow-

able level. The EPA then calculates the possible risk posed

by that proposed tolerance to determine if it is acceptable.

In calculating risk, the EPA estimates exposure based

on the “theoretical maximum residue concentration”

(TMRC) normally assuming three factors: that all of the

crop is treated, that residues on the crop are all at the maxi-

mum level, and that all consumers eat a certain fixed percent

of the commodity in their diet. This exposure calculation is

then compared to an “allowable daily intake” (ADI) and

calculated on the basis of the pesticide’s inherent toxicity.

The ADI represents the level of exposure in animal

tests at which there appears to be no significant toxicological

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pesticide residue

effects. If the residue level for that crop—the TMRC—

exceeds the allowable daily intake, then the tolerance will

not be granted as the residue level of the pesticide on that

crop is presumed unsafe. On the other hand, if the residue

level is lower than the ADI, then the tolerance would nor-

mally be approved. Exposure rates are based on assumptions

regarding the amount of treated commodities that an “aver-

age” adult person, weighing 132 lb (60 kg), eating an “aver-

age” diet would consume.

To set tolerances that are protective of human health,

the needs information about the anticipated amount of pesti-

cide residues found on food, the toxic effects of these resi-

dues, and estimates of the types and amounts of foods that

make up our diet. The

burden of proof

is on the manufac-

turer who has a vested interest in getting EPA approval. A

pesticide manufacturer begins the tolerance-setting process

by proposing a

tolerance level

, which is based on field trials

reflecting the maximum residue that may occur as a result

of the proposed use of the pesticide. The petitioner must

provide food residue and toxicity studies to show that the

proposed tolerance would not pose an unreasonable health

risk.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA)

requires that the manufacturer of any substances apply to

the EPA for a tolerance or maximum residue level to be

allowed in or on food. Because of the way pesticide residues

are defined and incorporated into the food additive provi-

sions of the FFDCA, there are actually several kinds of

tolerances, each subject to different decisional criteria. A

given pesticide can thus have many tolerances, both for use

on different crops and for any one crop. For example, for

each crop for which it is registered, a pesticide may need a

raw tolerance, a food additive tolerance, and an animal feed

tolerance, each of which will be subject to particular deci-

sional criteria.

The EPA sets tolerances on the basis of data the

manufacturer is required to submit on the nature, level, and

toxicity of a substance’s residue. According to the EPA,

one requirement is for the product chemistry data, which is

information about the content of the pesticide products,

including the concentration of the ingredients and any impu-

rities. The EPA also requires information about how plants

and animals metabolize (break down) pesticides to which

they are exposed and whether residues of the metabolized

pesticides are detectable in food or feed. Any products of

pesticide

metabolism

, or “metabolites,” that may be signifi-

cantly toxic are considered along with the pesticide itself in

setting tolerances.

The EPA also requires field experiments for pesticides

and their metabolites for each crop or crop group for which

a tolerance is requested. This includes each type of raw food

derived from the crop. Manufacturers must also provide

1076

information on residues found in many processed foods (such

as raisins), and in animal products if animals are exposed to

pesticides directly through their feed.

A pesticide’s potential for causing adverse health ef-

fects, such as

cancer

,

birth defects

, and other reproductive

disorders, and adverse effects on the nervous system or other

organs, is identified through a battery of tests. Tests are

conducted for both short-term or “acute” toxicity and long-

term or “chronic” toxicity. In several series of tests, laboratory

animals are exposed to different doses of a pesticide and

EPA scientists evaluate the tests to find the highest level of

exposure that did not cause any effect. This level is called

the “No Observed Effect Level” or NOEL.

Then, according to the EPA, the next step in the

process is to estimate the amount of the pesticide to which

the public may be exposed through the food supply. The

EPA uses the Dietary Risk Evaluation System (DRES) to

estimate the amount of the pesticide in the daily diet, which

is based upon a national food consumption survey conducted

by the

U.S. Department of Agriculture

. The USDA survey

provides information about the diets of the overall American

population and any number of subgroups, including several

different ethnic groups, regional populations, and age groups

such as infants and children.

Finally, for non-cancer risks, the EPA compares the

estimated amount of pesticide in the daily diet to the Refer-

ence Dose. If the DRES analysis indicates that the dose

consumed in the diet by the general public or key subgroups

exceeds the Reference Dose, then generally the EPA will

not approve the tolerance. For potential carcinogens, the

EPA ordinarily will not approve the tolerance if the dietary

analysis indicates that exposure will cause more than a negli-

gible risk of cancer.

There have been serious problems in carrying out the

law. Although the law requires a thorough tolerance review

for chemical pesticides prior to registration for health and

environmental impacts, the majority of pesticides currently

on the market and in use today were registered before mod-

ern testing requirements were established. “Thus,” according

to a 1987 report published by the

National Research Coun-

cil

Board on Agriculture, “many older pesticides do not

have an adequate data base, as judged by current standards,

particularly data about potential chronic health effects.”

The 1972 amendments to the

Federal Insecticide,

Fungicide and Rodenticide Act

(FIFRA) required a re-

view—or registration—of all then-registered products ac-

cording to contemporary standards. Originally, the EPA was

to complete the review of all registered products within three

years, but this process broke down completely. In 1978,

amendments were added to FIFRA that authorized the EPA

to group together individual substances by active ingredients

for an initial “generic” review of similar chemicals in order