Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Privatization movement

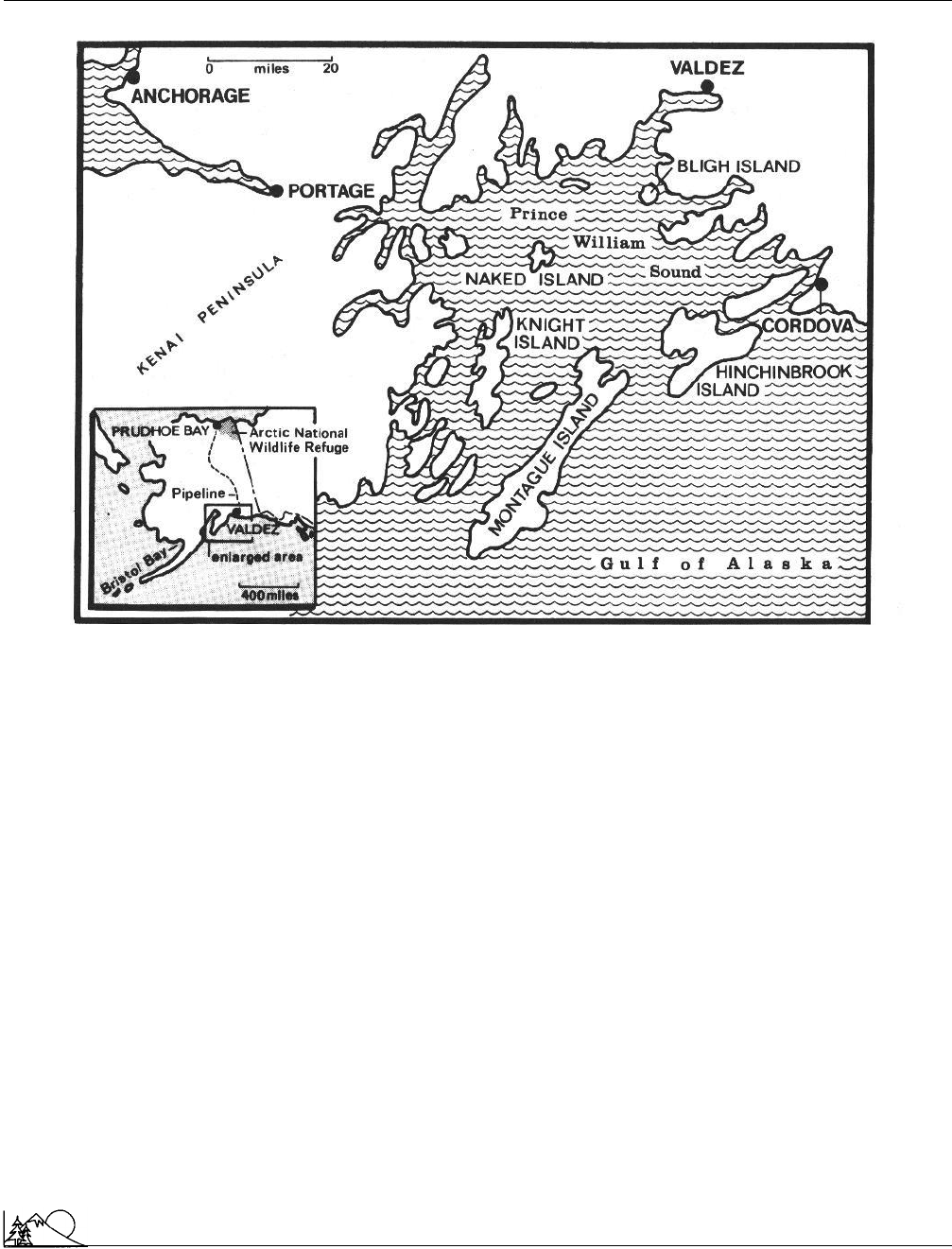

A map of Prince William Sound, Alaska. (The Conservation Fund. Reproduced by permission.)

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lethcoe, N., ed. Prince William Sound Environmental Reader, 1989: Exxon

Valdez Oil Spill. Valdez, AK: Prince William Sound Books, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Dold, C. A., et al. “Just the Facts: Prince William Sound.” Audubon 91

(1989): 80.

Heacox, K. “Sound of Silence.” Buzzworm 5 (January–February 1993): 52.

Steiner, R. “Probing an Oil-Stained Legacy.” National Wildlife 31 (April–

May 1993): 4–11.

Priority pollutant

Under the 1977 amendments to the

Clean Water Act

, the

Environmental Protection Agency

is required to compile a

list of priority toxic pollutants and to establish toxic pollutant

effluent

standards. A list of 126 key water pollutants was

produced by EPA in 1981, and is updated regularly, with

the updates appearing in the Code of Federal Regulations.

This list, consisting of metals and organic compounds and

known as the Priority Toxic Pollutant list, also prescribes

1137

numerical

water quality standards

for each compound.

State

water quality

programs must use these standards or

develop their own standards of at least equal stringency.

Privatization movement

This movement, initiated and supported primarily by econo-

mists, peaked in the early 1980s. Public ownership of land

was inefficient because the administration of the lands was

removed from the incentives and discipline of the free mar-

ket. The case for the transfer of these lands to the private

sector was made most strongly for lands managed for com-

modities (e.g., grazing lands, mineral lands, timber lands),

but some also advocated transferring

wilderness

lands to

the private sector, where it, too, would be more efficiently

managed. Many of the economists who supported the pro-

gram were a part of a movement referred to as the New

Resource Economics (NRE), which advocated an increased

reliance on private property rights and the free market for

managing

natural resources

. Such an approach meshed

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Probability

well with the Reagan Administration’s philosophy of free

market economics.

The privatization idea moved from theory to practice

in February 1982 at a Cabinet Council on Economic Affairs

meeting with the creation of the Asset Management Pro-

gram. This program was designed to identify federal property

for disposal, to develop legislation needed to dispose the

land, and to oversee the sale of the land. The program was

formalized by President Reagan in February 1982. The Fiscal

Year (FY) 1983 budget proposal called for the sale of 5

percent of the nation’s land (excluding Alaska), approxi-

mately 35 million acres, over five years. The revenues pro-

jected from the program were $17 billion from FY 1983

through FY 1987, the bulk of which was to come from

sales of

Bureau of Land Management

(BLM) and

Forest

Service

lands.

The BLM began to develop a program for land dis-

posal, but in July 1983, Secretary of the Interior James Watt

removed Interior Department lands from the Asset Manage-

ment Program. He thought that the program was a mistake

and was undermining the President’s support in the West

that had developed through the good neighbor program

(which had defused the

Sagebrush Rebellion

).

In the summer of 1982, the Forest Service began to

identify possible lands for disposal and announced that it

would seek legislative authority to dispose the land. In March

1983, the agency announced that it would seek legislative

authority to dispose of up to 6 million acres of land managed

by the Forest Service (3.2% of the lands in the system). At

this time, they indicated the specific amounts of land under

consideration for disposal in each state, with high figures of

872,054 acres in Montana and 36 percent of its land in Ohio.

Opposition to the Asset Management Program was

immediate and intense. The chief opponents were environ-

mentalists, but they were also joined by the forestry profes-

sion and many western politicians. This already strong oppo-

sition to the program intensified once the specific areas for

disposal were identified. In the face of this intense opposi-

tion, the Forest Service never presented legislation to Con-

gress to allow the sale of these lands. The attempt to put

privatization into practice was aborted by early 1984.

[Christopher McGrory Klyza]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Short, C. B. Ronald Reagan and the Public Lands: America’s Conservation

Debate, 1979–1984. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press,

1989.

Truluck, P. N., ed. Private Rights and Public Lands. Washington, DC:

Heritage Foundation, 1983.

1138

Probability

Probability is a quantity that describes the likelihood that

an event will occur. If an event is almost certain to occur,

the probability of the event is high. If the event is unlikely

to occur, the probability is low. Probability is represented

in

statistics

as a number between one and zero, and is

derived from the ratio of the number of potential outcomes

of interest to the number of all potential outcomes. For

example, if there are 52 cards in a deck and a card player is

equally likely to draw any card, then the probability of draw-

ing hearts is 1/4 or 0.25%. The probability of drawing a

king is 4/52 or 0.0769%. An event that has a probability of

one will always occur and an event that has a probability of

zero will never occur.

[Marie H. Bundy]

Project Eco-School

Project Eco-School (PES) is a nonprofit resource center

designed to promote

environmental education

by serving

as a link between schools and a vast library of environmental

information. PES was founded in 1989 by Jayni Chase and

her husband, comic-actor Chevy Chase, who were deter-

mined to foster greater environmental awareness by educat-

ing children.

Since its inception, PES has worked most closely with

schools and children in California. In Inglewood, for in-

stance, PES provided Worthington Elementary School with

an environmental library. The organization has also been

instrumental in developing consumer responsibility among

students. It promoted the Zero Waste Lunch, in which

students were encouraged to use reusable containers and

avoid using the more wasteful, disposable, and prepackaged

single-serving containers. The PES flyer “Guidelines for

Packing a Zero Waste Lunch” provided tips on

recycling

and stressed the importance of our actions and choices on

the

environment

.

Among PES’s notable publications isBlueprint for a

Green School, a reference book geared toward educating

young people about a host of environmental issues, including

recycling,

waste reduction

, and consumer alternatives. In

addition,Blueprint for a Green School provides instruction on

developing letter-writing campaigns and organizing a range

of schoolchildren’s activities such as field trips, community

services, and fund raising.

The newsletterGrapevine is an important element in

PES’s endeavor to promote environmental awareness. A typ-

ical issue provides coverage of events and environmental

activism in various schools throughout the country and re-

ports on

environmental policy

affecting the nation and the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Propellants

world. The newsletter also functions as a valuable networking

tool by providing readers with coverage of recent develop-

ments in environmental laws and publications. An “Eco-

Stars” segment details events relating to recently created

organizations, especially those directed to students.

[Les Stone]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Project Eco-School, 881 Alma Real Drive, Suite 301, Pacific Palisades,

CA USA 90272

Propellants

Propellants are used to disperse aerosols, powders and other

materials in a wide variety of applications. Consumers are

familiar with products such as cleaners, waxes, and spray

paints that are packaged in “aerosol spray cans” that use

propellants. In addition, many medical, commercial and in-

dustrial products use propellants. These products include

adhesives; document preservation sprays; portable fire extin-

guishing equipment; insecticides; sterilants; animal repel-

lants; medical devices such as anti-asthma inhalers and topi-

cal anesthetic applicators; lubricants, coatings and cleaning

fluids used in the electrical, electronic, and aerospace indus-

tries; and blowing agents and mold release agents used in

the production of foams, plastic and elastomeric materials.

In many cases, the propellant pressurizes, atomizes and deliv-

ers the product as an

aerosol

spray. In other cases, the

propellant itself is the sole or major “active ingredient” of

the product, usually for solvent and/or cleaning applications.

Aerosol sprays and other dispersions made possible

using propellants can form very small and uniform droplets

with controllable properties. These characteristics are desir-

able or necessary in critical applications where a very thin

layer or coating must be applied to a surface, e.g., as a

lubricant coating in an aerospace application. Additionally,

the small aerosols can be inhaled deeply into the lung and

the droplet itself may evaporate quickly, depending on the

product. Such characteristics help optimize the delivery of

drugs using medical inhalers.

The ideal propellant should generate sufficient volume

and pressure of vapor or gas for a particular application,

should be safe to humans and the

environment

, inert with

respect to reactions with other materials, miscible or highly

soluble in the product, easy to handle, and inexpensive. Each

chemical has its own physical and chemical properties that

affect the selection of a propellant for a given product and

application. Important properties are solvency, performance,

cost, and environmental considerations. Many of these prop-

erties are well characterized. For example, the solvency of a

1139

propellant can be measured as its solubility in water or other

chemicals

. Performance properties include the amount and

pressure of vapor generated from the liquid, measured as

vapor pressure, the volume of vapor generated per mass or

volume of the liquid, and the ratio of the volume of gas to

the volume of liquid. Performance also includes the range of

temperatures where the propellant will function adequately,

measured as the boiling and freezing points of the propellant,

and as the vapor generation rates at different temperatures.

The flammability of the propellant is another often critical

property, measured as the flammability limits in air and the

flash point. Additional properties that may be important

include the density of the liquid and gas, the critical tempera-

ture and pressure, the specific heat of gas and liquid, the

heat of vaporization, the viscosity of the liquid propellant,

the coefficient of liquid expansion, and the surface tension.

Environmental characteristics of propellants include the tox-

icity (often measured as

cancer

causing potency), the

ozone

depleting potential, the greenhouse warming potential, and

the reactivity (in terms of forming ground level ozone).

It is the environmental considerations that have brought

propellants forward in the last 20+ years as an national

and international environmental issue.

Restrictions on the Use of Propellants

Prior to the late 1970s, aerosol propellants were fre-

quently chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) propellants, and this use

constituted over 50% of total U.S. CFC consumption. At the

time, the most widely used CFCs were CFC-11 and CFC-

12. (These chemicals were also used in refrigeration, foam

blowing, and sterilization). Following concerns raised in 1974

regarding possible stratospheric ozone depletion resulting

from CFCs, the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and the

Foodand DrugAdministration

(FDA) acted

on March 17, 1978, to ban the use of CFCs as aerosol propel-

lants in all but essential applications. This reduced aerosol use

of CFCs by approximately 95% and achieved nearly a 50%

reduction in the U.S. consumption of CFCs. This reduction

was largely accomplished without economic penalty as con-

sumers voluntarily responded to advertising for “ozone safe”

substitutes. Also in the late 1970s, Canada and a few Nordic

nations banned or restricted aerosol propellant uses, also re-

sulting in a sharp drop in their total CFC use. Later in the

1980s, however, increases in other uses of CFCs, largely as

solvents, offset the earlier decreases.

The 1978 ban specifically exempted certain products

based on a determination of essentiality. Also excluded were

products where the CFC itself was the active ingredient or

sole ingredient in an aerosol or pressurized dispenser prod-

ucts, as this did not fit the ban’s narrow definition of an

“aerosol” propellant. These restrictions remained in effect

until 1990. Title VI of the 1990

Clean Air Act

Amendments

(CAAA) included provisions relevant to use of ozone deplet-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Propellants

ing chemicals used as propellants and expanded restrictions

for propellants. EPA’s response is the “Significant New Al-

ternatives Policy” (SNAP) Program which includes the eval-

uation of alternatives to ozone-depleting substances, includ-

ing an assessment of their

ozone layer depletion

potential,

global warming potential, toxicity, flammability, and expo-

sure potential (section 612 of the CAAA; 59 FR 13044).

In general, ozone-depleting substances are divided into

two classes with different product bans (section 610 in the

CAAA): Class I comprises CFCs,

halons

,

carbon

tetra-

chloride, methyl chloroform (MCF), hydrobromofluorocar-

bons and methyl bromide; and Class II comprises solely of

hydrochlorofluorocarbons

(HCFCs). EPA is to prohibit

the sale or distribution of certain “nonessential” products

(as determined by Congress and EPA) that release class I

substances, mandate the phaseout of class I and class II

substances (sections 604 and 605), review substitutes (section

612), and prohibit the sale of certain nonessential products

made with class I and class II substances (section 610). After

its review, EPA issued regulations on January 15, 1993 (58

FR 4767) which banned CFC propellants in aerosols and

other pressurized dispensers (and also in some other products

such as flexible and packaging foam). Exceptions were made

for a number of products, including certain medical devices;

lubricants for pharmaceutical and tablet manufacture; gauze

bandage adhesives and adhesive removers; topical anesthetic

and vapocoolant products; lubricants, coatings and cleaning

fluids for electrical and electronic equipment and aircraft

maintenance that contain CFC-11, CFC-12 or CFC-113;

release agents for molds used to produce plastic or elasto-

meric materials that contain CFC-11 or CFC-113; spinner-

ette lubricant/cleaning sprays used to produce synthetic fi-

bers that contain CFC-114; CFCs used as halogen

ion

sources in

plasma

etching; document preservation sprays

that contain CFC-113; and red pepper bear repellant sprays

that contain CFC-113. However, these products are not

exempted from the phase-out requirements for CFCs.

HCFCs can make excellent propellants, but their use

has been limited due to their cost and restrictions regarding

the class II ozone-depleting substances. In 1993, as a result

of increased taxation and CFC phase-out, HCFCs were

temporarily economically viable in applications where flam-

mability is a concern and cheaper alternatives (

hydrocar-

bons

) could not be used. However, section 610(d) of the

CAAA prohibits the sale or distribution of aerosol or foam

products that contain or are manufactured with class II sub-

stances after January 1, 1994. Again, exceptions and exclu-

sions from this ban have been made for “essential uses,” i.e.,

if necessary due to flammability or worker safety issues and

if the only available alternative is the use of a class I substance.

On December 30, 1993, EPA published a final rule (58 FR

69637) which exempted medical devices, lubricants, coatings

1140

or cleaning fluids for electrical, electronic equipment, and

aircraft maintenance, mold release agents used in the produc-

tion of plastic and elastomeric materials and synthetic fibers,

document preservation sprays containing HCFC-141b or

HCFC-22, portable fire extinguishing equipment sold to

commercial users, owners of boats, noncommercial aircraft,

and wasp and hornet sprays for use near high-tension power

lines. However, no other exceptions for class II propellants

were made since substitutes are available.

Propellant Alternatives and Substitutes

Due to the restrictions on propellants use, a large

number of propellant alternatives and substitutes have been

investigated. Both EPA and industry have been active in

this area.

Many products can be effectively packaged, distributed

and used without employing a propellant. For example, some

products are now sold for direct application as liquids or use

manually operated finger and trigger pumps, two-compart-

ment aerosol mechanism, mechanical pressure dispenser sys-

tems, and nonspray dispensers (e.g., solid stick dispensers).

The elimination of propellants altogether can be viable op-

tion for some products and applications. In other cases,

however, this may not provide proper dispersal or accurate

application of the product. Also, persons using manual

pumps or sprays may become fatigued with the constant

pumping motion and thus produce poor product perform-

ance. Because propellants are considered essential in a variety

of uses, there remains a need to find propellants that are

not environmentally damaging. Unfortunately, no propellant

exists which has all favorable properties. For example, some

CFC propellant substitutes, e.g., ammonia, butane and pen-

tane, have problems with toxicity and flammability. There

may be some essential applications for CFCs propellants for

which no practical substitutes exist, and the use of CFC

propellants in anti-asthma inhalers is a frequently cited ex-

ample.

A variety of propellants are being considered or are

being used as alternative propellants for class I and II con-

trolled substances. Each alternative propellant has its own

physical and chemical characteristics that influence its suit-

ability for a given application. The primary substitutes for

aerosol propellant uses of CFC-11, HCFC-22 and HCFC-

142b are saturated hydrocarbons (C3-C6); dimethyl ether;

compressed gases; and HFCs. A few EPA-approved alterna-

tive propellants are discussed below.

Of the hydrocarbons, butane, isobutane and propane

may be used singly or in mixtures. All have low boiling

points, are relatively nontoxic, inexpensive and readily avail-

able. (As with essentially any propellant, very high concen-

trations may result in asphyxiation because of the lack of

oxygen.) However, these propellants are flammable and, for

example, should not be used around electrical equipment if

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Public interest group

sparks could ignite the hydrocarbon propellant. To reduce

product flammability, hydrocarbons can be used with water-

based formulations. In the United States, nearly 50% of

aerosol propellants were using hydrocarbon propellants prior

to 1978, and nearly 90% in 1979 as a result of the CFC

ban. Propane/butane propellants have been used since 1987

in the Scandinavian market.

Dimethyl ether (DME) is a medium pressure, flamma-

ble, liquefied propellant generally used in combination with

other propellants. Its properties are similar to the hydro-

carbons.

Compressed gases, including

carbon dioxide

,

nitro-

gen

, air, and

nitrous oxide

, are used in applications where

a nonflammable propellant is necessary. These gases are

inexpensive, readily available, nonflammable (although cer-

tain temperatures and pressures of nitrous oxide may create

a moderate explosion risk), relatively nontoxic, and industrial

practices for using these substitutes are well established.

Since these gases are under significantly greater pressure

than CFCs and HCFCs, containers holding these gases

must be larger and bulkier, and safety precautions are neces-

sary during filling operations. Often, modifications must be

made to use compressed gases as they require new dispensing

mechanisms and stronger containers due to the greater pres-

sure; their low molecular weights restrict certain applications;

high pressure compressed gases dispel material faster which

may waste product; compressed gases cool upon expansion;

and finally, they are not well suited for applications that

require a fine and even dispersion. At present, about 7-9%

of the aerosol products use compressed gases, and their use

is expected to grow.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) such as HFC-134a,

HFC-125 and HFC-152a are partially fluorinated hydrocar-

bons, developed relatively recently and currently priced sig-

nificantly higher than HCFC-22. HFCs are less dense than

HCFC-22, but can provide good performance in applica-

tions (but not products such as noise horns, which require

a more dense gas). HFC-134a and HFC-125 are nonflam-

mable and have very low toxicity. HFC-152a is slightly

flammable. All three HFCs have zero ozone depletion po-

tential, but are potential

greenhouse gases

although their

atmospheric residence times are short. Additionally, these

HFCs are chemically reactive and they contribute to the

formation of tropospheric ozone. In ozone nonattainment

areas, state and local controls on VOCs may restrict the use

of these products. HFCs may be combined with flammable

propellants to reduce the flammability of the mixtures.

HFC-134a and HFC-227a are possible alternative propel-

lants in medical applications (currently using CFC-12 and

CFC-114). Approvals from both FDA and EPA are needed

for these applications.

[Stuart Batterman]

1141

Public Health Service

The United States Public Health Service is the health com-

ponent of the

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services

. It originated in 1798 with the organization of the

Marine Hospital Service, out of concern for the health of

the nation’s seafarers who brought diseases back to this

country. As immigrants came to America, they brought with

them

cholera

, smallpox, and yellow fever; the Public Health

Service was charged with protecting the nation from infec-

tious diseases.

Today the Service helps city and state health depart-

ments with health problems. Its responsibilities include con-

trolling infectious diseases, immunizing children, controlling

sexually transmitted diseases, preventing the spread of tuber-

culosis, and operating a quarantine program.

The Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia,

is the Public Health Service agency responsible for promot-

ing health and preventing disease.

Public interest group

Public interest groups may be defined as those groups pursu-

ing goals the achievement of which ostensibly will provide

benefits to the public at large, or at least to a broader popula-

tion than the group’s own membership. Thus, for example,

if a public interest group concerned with

air quality

is

successful in its various strategies and activities, the achieved

benefit--cleaner air--is available to the public at large, not

merely to the group’s members. The competition of interest

groups, each pursuing either its own good or its conception

of the public good, has been an increasingly prominent fea-

ture of American politics in the latter half of the twentieth

century.

There is no single, universally applicable definition or

test of the public good, and thus there is often a great deal

of disagreement about what happens to be in the public

interest, with different public interest groups taking quite

different positions on various issues. In any particular politi-

cal controversy, moreover, there may be several quite differ-

ent public interests at stake. For example, the question of

whether to build a nuclear-powered generator plant may

involve competing public interests in the protection of the

environment

from

radioactive waste

and other dangers,

the maintenance of public safety, and the promotion of

economic growth, among others.

Similarly, the question of who benefits from the activi-

ties of a public interest group can also be quite complicated.

Some benefits that are generally available to the public may

not be equally available or accessible to everyone. If

wilder-

ness

preservation groups are successful, for example, in hav-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Public land

ing land set aside in, say, Maine, that land is in principle

available to potential recreational users from all over the

country. But people from New England will find that benefit

much more accessible than people from another region.

The membership, resources, and number of active

public interest groups in the United States have all increased

dramatically in the previous twenty-five years. There are

now well over 2,500 national organizations promoting the

public interest, as determined from almost every conceivable

viewpoint, in a wide variety of issue areas. Over 40 million

individual members support these groups with membership

fees and other contributions totalling more than $4 billion

every year. Many groups find additional support from various

corporations, private foundations, and governmental

agencies.

This growth in the public interest sector has been

more than matched by, and partly was a response to, a similar

explosion in the number and activities of organized interest

groups and other politically active organizations pursuing

benefits available only or primarily to their own members.

Public interest groups often provide an effective counter-

weight to the activities of these more narrowly-oriented

associations.

The growth of interest group politics has not been

without its negative consequences. Some critics argue that

every interest group, including “public interest groups,” ulti-

mately pursues relatively narrow goals important mainly to

fairly limited constituencies. A politics based on the competi-

tion of these groups may be one in which well-organized

narrow interests prevail over less well-organized broader in-

terests. It may also produce decreased governmental per-

formance and economic inefficiencies of various types. Public

interest groups, moreover, seem to draw most of their sup-

port and membership from the middle and upper economic

strata, whose interests and concerns are then disproportion-

ately influential.

[Lawrence J. Biskowski]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Berry, J. M. The Interest Group Society. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

Cigler, A. J., and B. A. Loomis, eds. Interest Group Politics. Washington,

DC: CQ Press, 1991.

McFarland, A. S. Public Interest Lobbies. Washington, DC: The American

Enterprise Institute, 1976.

Schlozman, K. L., and J. T. Tierney. Organized Interests and American

Democracy. New York: Harper and Row, 1986.

Public Interest Research Group

see

U.S. Public Interest Research Group

1142

Public land

Public land refers to land owned by the government. Most

frequently, it is used to refer to land owned and managed

by the United States government, although it is sometimes

used to refer to lands owned by state governments. The U.S.

government owns 262 million acres, about one eighth of the

land in the country, the bulk of which is located in the

western states, including Alaska. The lands are managed

primarily by the

Bureau of Land Management

, the De-

partment of Defense, the

Fish and Wildlife Service

, the

Forest Service

, and the

National Park Service

.

Public Lands Council

An important environmental debate is currently focused on

the use of public lands by livestock owners, particularly own-

ers of cattle and sheep. Historically, the federal government

has sold leases and permits for grazing on

public land

to

these individuals at very low prices, often a few cents per acre.

In recent years, many environmentalists have argued

that cattle are responsible for the destruction of large tracts of

rangeland in the western states. They believe the government

should either greatly increase the rates they charge for the

use of western lands or prohibit grazing entirely on large

parts of it. In response, livestock owners have claimed that

they practice good-land management techniques and that

in many cases the land is in better condition than it was

before they began using it.

The Public Lands Council (PLC) is one of the primary

groups representing those who use public lands for grazing.

It is a nonprofit corporation that represents approximately

31,000 individuals and groups who hold permits and leases

allowing them to use federal lands in 14 western states for

the grazing of livestock. Twenty-six state groups belong to

the council, and in addition, the council coordinates the

public lands policies of three other organizations, the Na-

tional Cattlemen’s Association, the American Sheep Indus-

try Association, and the Association of National

Grass-

lands

.

The PLC also represents the interests of public land

ranchers before the United States Congress. It lobbies and

monitors Congress and various federal agencies responsible

for grazing, water use,

wilderness

,

wildlife

, and other fed-

eral land management policies that are of concern to the

livestock industry.

The council was founded in 1968 for the purpose of

promoting principles of sound management of federal lands

for grazing and other purposes. The council obtains its funds

from dues collected by state organizations and by contribu-

tions from other organizations it represents. It has two classes

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task Force

of membership. General members are those who belong to

a state organization that contributes to the PLC or those

who make individual contributions. Voting members are

elected by the general membership of each state, which may

have a maximum of four voting members. Voting members

meet at least once each year to establish PLC policy.

The PLC maintains a 500-volume library at its offices

in Washington, D.C. It also publishes a quarterly newsletter,

as well as news releases on specific issues, and regular col-

umns in various western livestock publications. The council

has also sponsored workshops and seminars on issues of

importance to users of federal lands.

The American Lands and Resources Foundation has

been established as an arm of the council for the purpose

of receiving charitable and tax-deductible contributions to

be used for the education of the general public about the

benefits of using federal lands for livestock grazing.

[David E. Newton]

Public trust

The public trust doctrine is a legal doctrine dealing with the

protection of certain uses and resources for public purposes,

regardless of ownership. These uses or resources must be

made available to the public, regardless of whether they are

under public or private control. That is, they are held in

trust for the public.

The modern public trust doctrine can be traced back

at least as far as Roman civil law. It was further developed

in English law as “things common to all.” This public trust

was applied mostly to navigation: the Crown possessed the

ocean, the rivers, and the lands underlying these bodies of

water (referred to as jus publicum). These were to be con-

trolled in order to guarantee the public benefit of free navi-

gation.

In the United States, the public trust doctrine is rooted

in Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois (1892). In this case,

the Supreme Court ruled that a grant held by the Illinois

Central Railroad of the Chicago waterfront was void because

it violated the state’s public trust responsibilities to protect

the rights of its citizens to navigate and fish in these waters.

In making this decision, the court relied on English common

law and served to underscore the existence of the public

trust doctrine in the United States.

As a trustee, the government (federal or state) faces

certain restrictions in protecting the public trust. These in-

clude using the trust property for common purpose and

making it available for use by the public; not selling the trust

property; and maintaining the trust property for particular

types of uses. If any of these responsibilities are violated,

1143

the government can be sued by its citizens for neglecting its

trust responsibilities.

With the rise of the environmental movement, the

public trust doctrine has been applied with greater frequency

and to a broader array of subjects. In addition to navigable

waters, the doctrine has been applied to

wetlands

, state

and national parks, and fossil beds. This expanded use of

the doctrine has led to increased conflict. On the ground,

there has been growing conflict over the limitations of private

property. Landholders who find their actions limited argue

that the public trust doctrine is a way to mask indirect

takings

and argue that they deserve just compensation in

return for the restrictions. Among legal scholars, there is

concern that the public trust doctrine is not firmly grounded

in the law and simply reflects the opinions of judges in

various cases. Proponents of the public trust doctrine, how-

ever, argue that it is a useful vehicle to temper unrestricted

private property rights in the United States. Indeed, it has

been argued that if public trust rights exist in private prop-

erty, then no takings can occur since the regulation is merely

recognizing the pre-existing limitation in the property.

[Christopher McGrory Klyza]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Plater, Z. J. B., R. H. Abrams, and W. Goldfarb, eds. Environmental Law

and Policy: Nature, Law, and Society. New York: West Publishing, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Brady, T. P. “’But Most of It Belongs to Those Yet to be Born:’ The

Public Trust Doctrine, NEPA, and the Stewardship Ethic.” Boston College

Environmental Law Review 17 (1990): 621–46.

Kagan, D. G. “Property Rights and the Public Trust: Opposing Lakeshore

Funnel Development.” Boston College Environmental Law Review 15

(1987): 105–34.

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin

International Task Force

The Puget Sound/Georgia Basin

ecosystem

consists of

three shallow marine basins: the Strait of Georgia to the

north, Puget Sound to the south, and the Strait of Juan de

Fuca that connects this inland sea to the Pacific Ocean.

In addition to open water, the ecosystem includes islands,

shorelines,

wetlands

, and the watersheds of several moun-

tain ranges whose freshwater rivers dilute the salt water.

This rich and diverse ecosystem spans the United States-

Canadian border and is threatened by

population growth

,

urbanization, agriculture, and industry. In addition to Pacific

salmon

, valuable ground fish, and marine mammals includ-

ing orca

whales

, Puget Sound/Georgia Basin has three

of North America’s busiest ports—Seattle, Tacoma, and

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task Force

Vancouver, British Columbia (B.C.). Already an estimated

58% of the coastal wetlands of Puget Sound and 18% of the

Strait of Georgia wetlands, which provide vital

habitat

to

fish and birds, have been lost to development.

The Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task

Force was created 1992 by the B.C./Washington Environ-

mental Cooperation Council to coordinate priority environ-

mental efforts between the state of Washington and the

Canadian province of British Columbia. The task force in-

cludes representatives from the U.S.

Environmental Protec-

tion Agency

(EPA), the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

,

the Northwest Fisheries Science Center, the Department of

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

, and the Department of

Environment Canada

. State and provincial representation

include the Washington Departments of Ecology, Natural

Resources, and Fish and Wildlife and the B.C. Ministries

of Water, Land and Air Protection and Sustainable Resource

Management (formerly combined under the B.C. Ministry

of Environment, Lands and Parks). The task force also

includes representatives from the Puget Sound

Water Qual-

ity

Action Team, the Northwest Straits Commission, the

Coast Salish Sea Council, and the Northwest Indian Fisher-

ies Commission. The task force is charged with addressing

marine, near-shore, and shoreline environmental issues for

the entire Puget Sound/Georgia Basin shared ecosystem, as

well as identifying and responding to new issues that may

affect the shared waters.

The task force pursues project funding and promotes

communication and cooperation among federal, state, pro-

vincial, local, and tribal/aboriginal governments and groups.

In 1994, a Marine Science Panel (MSP), made up of Wash-

ington and B.C. scientists, identified priority environmental

issues to be addressed by the task force’s working groups.

The task force cooperates with government agencies on im-

plementation of the working groups’ proposals.

The MSP recommended that fish and

wildlife man-

agement

shift its goal from maximum sustainable harvest

to

species

protection. To this end, the task force’s highest

priority issues are protecting marine life, establishing

marine

protected areas

(MPAs), and preventing near-shore and

wetland habitat loss and the introduction of exotic or non-

indigenous species (NIS). The Task Force Work Group on

Marine Protected Areas has conducted an assessment of

Puget Sound MPAs. The B.C. Nearshore Habitat Loss

Work Group has devised a plan for preventing coastal habitat

loss in the Georgia Basin. The Washington Aquatic Nui-

sance Species Coordination Committee and the B.C. Work-

ing Group on Non-Indigenous Species have worked to de-

velop nuisance species legislation and proposals for

regulating ballast water release from ships, a major source

of NIS introduction. In collaboration with various agencies,

the task force has launched a public NIS education program.

1144

The medium priority recommendations of the MSP

included the control of toxic waste discharges and the pre-

vention of large

oil spills

and major diversions of freshwater

for

dams

and other projects. The Washington and B.C.

toxic chemical work groups have undertaken research, inven-

toried contaminated sites, and assessed the movement of

toxic

chemicals

through the shared waters.

On May 15, 2002 the Transboundary Georgia Basin-

Puget Sound Environmental Indicators Working Group re-

leased their ecosystem indicators report, concluding that

population growth constitutes the primary threat to the re-

gion. During the 1990s, the region’s population grew by

about 20% to seven million people. It is projected to grow

another 32% by 2020. Whereas most of the growth during

the 1990s was in urban areas, new growth is expected to occur

in more rural areas. The report found that

air pollution

from

inhalable particles has declined since 1994; the amount of

waste produced per person has remained about the same;

and

recycling

has increased, particularly in B.C. However

the loss of stream and shoreline habitats to development is

endangering the region’s plants and animals. In the Georgia

Basin almost 35% of the freshwater fish and 12% of the

reptiles are in danger of

extinction

, as are 18% of Puget

Sound’s freshwater fish and 25% of its reptiles. The harbor

seals

of Puget Sound are much more heavily contaminated

with

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs) than the Strait

of Georgia seals. PCB contamination levels have remained

constant for more than 14 years, despite major cleanup ef-

forts. The harbor seals also are contaminated with other

persistent organic pollutants

including dioxins and

fu-

rans

. The report found that most of the ecosystem’s pro-

tected land is in the mountains: only 1% of land below 3,000

ft (914 m) is protected.

[Margaret Alic Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Mills, Mary Lou. Strategy and Recommended Action List for Protection and

Restoration of Marine Life in the Inland Waters of Washington State. Seattle:

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task Force, 1999.

O

THER

The British Columbia Nearshore Habitat Loss Work Group. A Strategy

to Prevent Coastal Habitat Loss and Degradation in the Georgia Basin. June

2001 [May 2002]. <www.wa.gov/pswqat/shared/pdfs/Coastal_main.pdf>.

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task Force. Pathways to Our

Optimal Future: A Five-Year Review of the Activities of the International

Task Force. Puget Sound-Georgia Basin Environmental Initiative. [May

2002]. <http://www.wa.gov/puget_sound/shared/pdfs/_December_1_f.

al_in_sequenc.pdf>.

“Shared Waters, Puget Sound On-Line.” Puget Sound/Georgia Basin Inter-

national Task Force. [May 2002]. <www.wa.gov/pswqat/shared/

backgrnd.html>.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Pulp and paper mills

Transboundary Georgia Basin-Puget Sound Environmental Indicators

Working Group. Georgia Basin-Puget Sound Ecosystem Indicators Report.

May 15, 2002 [June 2002]. <wlapwww.gov.bc.ca/cppl/gbpsei/index.html>.

Washington Sea Grant Program. Shared Waters: The Vulnerable Inland Sea

of British Columbia and Washington. Shared Waters, Puget Sound On-

Line. [May 2002]. <www.wa.gov/pswqat/shared/bcwaswl.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, PO Box 9360 Stn Prov Govt,

Victoria, BCCanada V8W 9M2 (250) 387-9422, Fax: (250) 356-6464,

<http://www.gov.bc.ca/wlap>

Puget Sound/Georgia Basin International Task Force, Email:

jdohrmann@psat.wa.gov, <http://www.wa.gov/puget_sound/shared/

shared.html>

Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team, PO Box 40900, Olympia, WA

USA 98504-0900 (360) 407-7300, Toll Free: (800) 54-SOUND, <http://

www.wa.gov/puget_sound>

Pulp and paper mills

Pulp and paper mills take wood and transform the raw

product into paper. Hardwood logs (beech, birch, and maple)

and softwoods (pine, spruce, and fir) are harvested from

managed forestlands or purchased from local farms and tim-

berlands across the world and are transported to mills for

processing. Hardwoods are more dense, shorter fibered, and

slower growing. Softwoods are less dense, longer fibered,

and faster growing.

Today, the process is mainly done with high tech,

sophisticated machinery. Wood products, which consist of

lignin (30 percent), fiber (50 percent), and other materials--

carbohydrates, proteins, fats, turpentine, resins, etc., (20 per-

cent) are transformed into paper consisting of fiber, and

additives--clay, titanium dioxide, calcium carbonate, water,

rosin, alum, starches, gums, dyes, synthetic polymers, and

pigments. Wood is about 50 percent cellulose fiber. The

structure of paper is a tightly bonded web of cellulose fibers.

About 80 percent of a typical printing paper by weight is

cellulose fiber. First in the process, the standard eight-foot

(2.4-m) logs are debarked by tumbling them in a giant

barking drum and then chipped by a machine that reduces

them to half-inch chips. The chips are cooked, after being

screened and steamed, in a digester using sodium bisulfite

cooking liquor to remove most of the lignin, the sticky matter

in a tree that bonds the cellulose fibers together. This is the

pulping process.

Then the chips are washed, refined, and cleaned to

separate the cellulose fibers and create the watery suspension

called pulp. The pulp is bleached in a two-stage process

with a number of possible

chemicals

. Those companies that

choose to avoid

chlorine

bleach will use

hydrogen

peroxide

and sodium hydrosulfite which yields a northern high-yield

hardwood sulfite pulp. This pulp is blended with additional

softwood kraft pulp after refining as part of the stock prepara-

tion process, which involves adding such materials as dyes,

1145

pigments, clay fillers, internal sizing, additional brighteners,

and opacifiers.

Late in the process, the stock is further refined to

adjust fiber length and

drainage

characteristics for good

formation and bonding strength. The consistency of the

stock is reduced by adding more water and the stock is

cleaned again to remove foreign particles. The product is

then pumped to the paper machine headbox.

From here, the dilute stock (99.5 percent water) flows

out in a uniformly thin slice onto a Fourdrinier wire--an

endless moving screen that drains water from the stock to

form a self-supporting web of paper. The web moves off

the wire into the press section which squeezes out more

water between two press felts, then into the first drier section

where more moisture is removed by evaporation as the paper

web winds forward around an array of steam-heated drums.

At the size press, a water-resistant surface sizing is added

in an immersion bath.

From there the sheet enters a second drier section

where the sheet is redried to the final desired moisture level

before passing through the computer scanner. The scanner is

part of a system for automatically monitoring and regulating

basis weight and moisture. The paper enters the calendar

stack, where massive steel polishing rolls give the sheet its

final machine finish and bulking properties.

The web of paper is then wound up in a single long

reel, which is cut and moved off the paper machine to a

slitter/winder machine which slices the reel into rolls of the

desired width and rewinds them onto the appropriate cores.

The rolls are then conveyed to the finishing room where

they are weighed, wrapped, labeled, and shipped.

In practice, all papers, even newsprint, are pulp blends,

but they are placed in one of two categories for convenient

description: groundwood and free sheet. And in practice,

other pulp varieties enter into the picture. They may be

reclaimed pulps such as de-inked or post-consumer waste;

recycled pulps which included scraps, trim, and unprinted

waste; cotton fiber pulps; synthetic fibers; and pulps from

plants other than trees: bagasse, esparto, bamboo, hemp,

water hyacinth

; and banana, or rice. But the dominant raw

material remains wood pulp. Paper makers choose and blend

from the spectrum of pulps according to the demands on

their grades for strength, cleanliness, brightness, opacity,

printing, and converting requirements, aesthetics, and mar-

ket price.

From cotton fiber-based sheets to the less expensive

papers made from groundwood, to recycled grades manufac-

tured with various percentages of wastepaper content, pa-

permakers have consistently responded to the need of the

marketplace. In today’s increasingly environmentally con-

scious marketplace, papermakers are being called on to pro-

duce pulp that is environmentally friendly. Eliminating chlo-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Purple loosestrife

rine from the bleaching process is a major step in eliminating

unwanted

toxins

. The changeover costs money and is the

source of controversy here in the United States.

However, the chlorine-free trend has taken a firm hold

in Europe. All of Sweden requires its printing and writing

paper mills to be chlorine-free by the year 2010. France,

Germany, and several other countries have several mills that

are reported to be chlorine-free and the trend is moving

across Canada.

While there are growing exceptions, most North

American mills still use a chlorine bleaching process to create

a bright, white pulp. Why the need to eliminate the

chemical?

In the bleaching process, chlorine, chlorine dioxide,

and other chlorine compounds create toxic byproducts.

These byproducts consist of over 1,000 chemicals, some of

which are the most toxic known to man. The list includes:

dioxin

and other organochlorines compounds such as PCBs,

DDT,

chlordane

, aldrin, dieldrin,

toxaphene

, chloroform,

heptachlor and

furans

. These are formed by the reaction

of lignin in the pulp with chlorine or chlorine-based com-

pounds used in the bleaching sequence of all kraft pulps.

These unwanted chemicals byproducts must be dis-

charged and end up in the

effluent

. The effluent is released

into our rivers, lakes and streams and is threatening the

groundwater

and our drinking water, as well as the food

chain through fish and birds. Epidemic health effects among

thirteen

species

of fish and

wildlife

near the top of the

Great Lakes

food web have been identified. Not only are

these toxic chemicals causing

cancer

and birth deformities

in humans and wildlife, but they are very persistent, building

up in our waterways and eventually into our bodies.

Dioxin traces have been found in papers and even in

coffee from chlorine-bleached coffee

filters

and milk from

chlorine-bleached milk cartons, as well as in women’s hy-

giene products. Most of the paper being sold in the United

States today as “dioxin free” is actually “dioxin undetectable.”

That is because dioxin can be measured in

parts per trillion

or parts per quintillion, but beyond that level, there are no

scientific measurements sophisticated enough. Or if measur-

able, the process becomes very expensive. (If exposed often

enough, even these minuscule quantities build up in the

environment

and in humans.) To be truly dioxin free, the

paper must be made from pulps that have been bleached

without chlorine or chlorine-based compounds.

The newer trend is to eliminate chlorine from the

bleaching process completely. Some North American mills

are turning to hydrogen peroxide, oxygen brightening, or

ozone

brightening. These compounds do not produce di-

oxin or other organochlorine compounds and are considered

“environmentally-sound.” The United States pulp and paper

1146

industry has sharply reduced its use of the chemical and

plans to curtail use further during the next few years.

In part, this reduction can be traced to the increased

sophistication of pulp and paper plants during the past de-

cade. The cooking and bleaching operations have been fine-

tuned. Wood chips are cooked more before they go to the

bleach plant, so less bleaching is required. Also, in some

plants, industry is trying chlorine dioxide as a substitute; it

produces less dioxin, but still contains chlorine.

The result of these changes means an 80 percent reduc-

tion in the amount of dioxin associated with bleaching.

Between 1988-1989, a total of 2.5 lb (11.1 kg) of dioxin

was produced. As of 1993, that number fell below 8 ounces

(22.7 g) per year. Eight ounces sound like a small amount,

but scientists measure dioxin in

parts per million

, billion,

trillion and quintillion, so eight ounces is still too high.

A number of lawsuits have been filed by residents

living near or downstream of dioxin-contaminated pulp mills

because of the health threats. The more the plaintiffs win,

the sooner will the use of chlorine be eliminated completely.

It is estimated that the amount of chlorine used in pulp and

paper bleaching will fall from 1.4 million tons in 1990 to

920,000 tons by 1995.The eventual goal is

zero discharge

.

[Liane Clorfene Casten]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ferguson, K. Environmental Solutions for the Pulp and Paper Industry. San

Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

Jenish, D. “Cleaning Up a Chemical Soup.” Maclean’s 103 (29 January

1990): 32–4.

Purple loosestrife

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is an aggressive wetland

plant

species

first introduced into the United States from

Europe. It is a showy, attractive plant that grows up to 4

feet (1.2 m) in height with pink and purple flowers arranged

on a spike, and it is common in shallow marshes and lake-

shores all across the northern half of the United States.

Loosestrife is a perennial plant species that spreads

rapidly because of the high quantity of seeds it produces

(sometimes up to 300,000 seeds per plant) and the efficient

dispersal of seeds by wind and water. The plant has a well-

developed root system and is able to tolerate a variety of

soil

moisture conditions. This has made it an effective colo-

nizer of disturbed ground as well as areas with fluctuating