Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

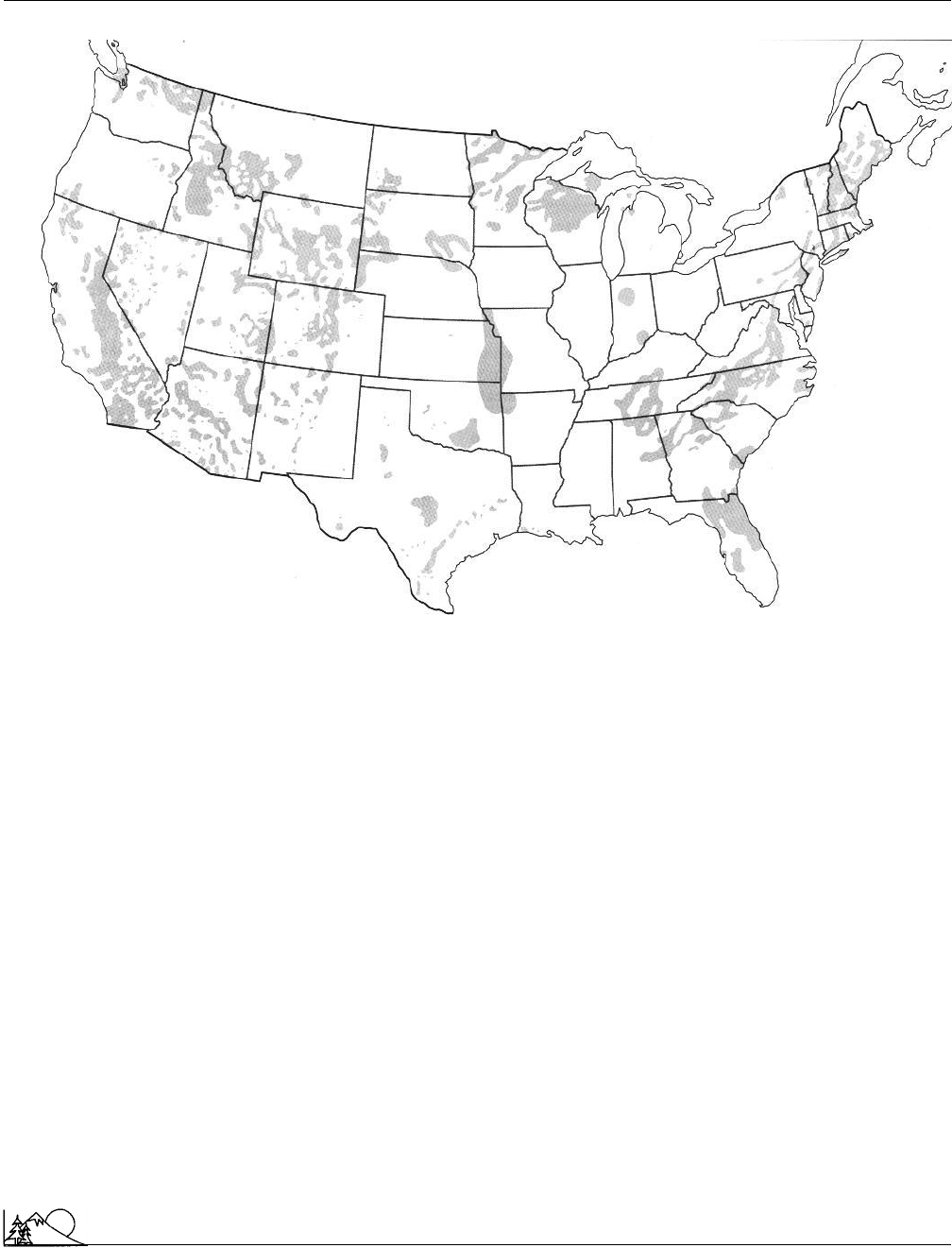

The shaded areas on the map have potentially high levels of uranium in the soil and rocks. Radon levels may

be high in these areas. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

dying the problem. See also Radiation exposure; Radioactive

decay; Radioactive pollution; Radioactivity

[Usha Vedagiri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brenner, D. J. Radon: Risk and Remedy. Salt Lake City: W. H. Free-

man, 1989.

Cohen, B. Radon: A Homeowner’s Guide to Detection and Control. Mt.

Vernon, NY: Consumer Report Books, 1988.

Kay, J. G., et al. Indoor Air Pollution: Radon, Bioaerosols, and VOCs. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1991.

Lafavore, M. Radon: The Invisible Threat. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press, 1987.

Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

In 1985, the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, a non-profit orga-

nization, was established to convert abandoned railroad cor-

ridors into open spaces for public use. During the nineteenth

century, the railroad industry in the United States boomed

1167

as rail companies rushed to acquire land and assemble the

largest rail system in the world. By 1916, over 250,000

mi (402,000) of track had been laid across the country,

connecting even the most remote towns to the rest of the

nation. However, during the next few decades, the

automo-

bile

drastically changed the way Americans live and travel.

With Henry Ford’s introduction of mass production

techniques, the automobile became affordable for nearly ev-

eryone, and industry shifted to trucking for much of its

overland

transportation

. The invention and widespread use

of airplanes had a significant impact on the railroad industry

as well, and people began abandoning railroad transpor-

tation.

As a result of these developments, thousands of miles

of rail corridors fell into disuse. Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

estimates that over 3,000 mi (4,828 km) of track are aban-

doned each year. Since much of the track is in the public

domain, Rails-to-Trails strives to find uses for the land that

will benefit the public. Thus Rails-to-Trails works with

citizen groups, public agencies, railroads, and other con-

cerned parties to, according to the organization, “build a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rain forest

transcontinental trailway network that will preserve for the

future our nation’s spectacular railroad corridor system.”

Some of the rails have been converted to trails for

hiking, biking, and cross-country skiing as well as

wildlife

habitats. By providing people with information about up-

coming abandonments, assisting public and private agencies

in the effort to gain control of those lands, sponsoring short-

term land purchases, and working with Congress and other

federal and state agencies to simplify the acquisition of aban-

doned railways, Rails-to-Trails has mobilized a powerful

grassroots movement across the country. Today there are

over 11,500 mi (18,506 km) of converted rails-to-trails.

Rails-to-Trails also sponsors an annual conference and

other special meetings and publishes materials related to

railway

conservation

. Its quarterly newsletter, Trailblazer,

is sent to members and keeps them aware of rails-to-trails

issues. Many books and pamphlets are available through the

group, as are studies such as How to Get Involved with the

Rails-to-Trails Movement and The Economic Benefits of Rails-

to-Trails Conversions to Local Economies. In addition, the

Rails-to-Trails Conservancy provides legal support and ad-

vice to local groups seeking to convert rails to trails.

[Linda M. Ross]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. 1100 17th Street, 10th Floor, NW,

Washington, D.C. USA 20036. (202) 331-9696, Email:

railtrails@transact.org, <http://www.railtrails.org>.

Rain forest

The world’s rain forests are the richest ecosystems on Earth,

containing an incredible variety of plant and animal life.

These forests play an important role in maintaining the

health and

biodiversity

of the planet. But rain forests

throughout the world are rapidly being destroyed, threaten-

ing the survival of millions of

species

of plants and animals

and disrupting

climate

and weather patterns. The rain for-

ests of greatest concern are those located in tropical regions,

particularly those found in Central and South America, and

the ancient temperate rain forests along the northeastern

coast of North America.

Tropical rain forests (TRFs) are amazingly rich and

diverse biologically and may contain one-half to two-thirds

of all species of plants and animals, though these forests

cover only about 5–7% of the world’s land surface. Tropical

rain forests are found near the equatorial regions of Central

and South America, Africa, Asia, and on Pacific Islands,

with the largest remaining forest being the Amazon rain

forest, which covers a third of South America.

1168

TRFs remain warm, green, and humid throughout the

year and receive at least 150 in (4 m) of rain annually, up

to half of which may come from trees giving off water

through the pores of their leaves in a process called

transpi-

ration

. The tall, lush trees of the forest form a two- to

three-layer closed canopy, allowing very little light to reach

the ground. Although tropical forests are known for their

lush, green vegetation, the

soil

stores very few nutrients.

Dead and decomposing animals, trees, and leaves are quickly

taken up by forest organisms, and very little is absorbed into

the ground.

In 1989 World Resources Institute predicted that “be-

tween 1990 and 2020, species extinctions caused primarily

by tropical

deforestation

may eliminate somewhere be-

tween 5–15% of the world’s species...This would amount to

a potential loss of 15,000 to 50,000 species per year, or 50

to 150 species per day.” It is estimated that 30–80 million

species of insects alone may exist in TRFs, at least 97% of

which have never been identified or even discovered.

Tropical forests also provide essential winter

habitat

for many birds that breed and spend the rest of the year in

the United States. Some 250 species found in the United

States and Canada spend the winter in the tropics, but their

population levels are decreasing alarmingly due to forest

depletion.

Tropical rain forests have unique resources, many of

which have yet to be utilized. Food, industrial products, and

medicinal supplies are common examples. Among the many

fruits, nuts, and vegetables that we use on a regular basis

and which originated in tropical forests are citrus fruits,

coffee, yams, nuts, chocolate, peppers, and cola. A variety

of oils, lubricants, resins, dyes, and steroids are also products

of the forests. Natural

rubber

, the fourth biggest agricultural

export of southeast Asian nations, brings in over $3 billion

a year to developing countries. The forests could also yield

a sustainable supply of woods like teak, mahogany, bamboo,

and others. Although only about 1% of known tropical plants

have been studied for medicinal or pharmaceutical applica-

tions, these have produced 25–40% of all prescription drugs

used in the United States. Some 2,000 tropical plants now

being studied have shown potential as cancer-fighting

agents.

Scientists studying ways to commercially utilize these

forests in a sustainable, non-destructive way have determined

that two to three times more money could be made from

the long-term collection of such products as nuts, rubber,

medicines, and food, as from cutting the trees for

logging

or cattle ranching. Perhaps the greatest value of tropical rain

forests is the essential role they play in the earth’s climate. By

absorbing

carbon dioxide

and producing oxygen through

photosynthesis

, the forests help prevent global warming

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rain forest

(the

greenhouse effect

) and are important in generating

oxygen for the planet. The forests help prevent droughts and

flooding

, soil

erosion

and stream

sedimentation

, maintain

the

hydrologic cycle

, and keep streams and rivers flowing

by absorbing rainfall and releasing moisture into the air.

Despite the worldwide outcry over deforestation, de-

struction is actually increasing. A 1990 study by the United

Nations Food and Agriculture Organization found that trop-

ical forests were disappearing at a rate exceeding 40 million

acres (16.2 million ha) a year—an area the size of Washing-

ton state. This rate is almost twice that of the previous

decade.

Timber companies in the United States and western

Europe are responsible for most of this destruction, mainly

through farming, cattle ranching, logging, and huge develop-

ment projects. Japan, the world’s largest hardwood importer,

buys 40% of the timber produced, with the United States a

close second. Ironically, much of the destruction of forests

worldwide has been paid for by American taxpayers through

such government-funded international lending and develop-

ment agencies as the

World Bank

, the International Mone-

tary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank,

along with the United States Agency for International De-

velopment.

The release of the World Bank’s new Operational

Policy on Forests has been delayed since October 2001, and

had not been released as of the first week in July 2002. The

release has been delayed by a World Bank dispute over

whether its new Forest Policy would apply to the World

Bank’s growing area of lending, which directly or indirectly

finances logging activities. There has been widespread de-

mand that the Forest Policy must apply to all World Bank

operations that might have an impact on forests. It remains

to be seen how the Operational Policy on Forests will handle

this important question.

American, European, and Latin American demand

for beef has contributed heavily to the conversion of rain

forest to pasture land. It is estimated that one-fourth of all

tropical forests destroyed each year are cut and cleared for

cattle ranching. Between 1950 and 1980, two-thirds of Cen-

tral America’s primary forests were cut, mostly to supply the

United States with beef for fast food outlets and pet food.

In Brazil and other parts of the

Amazon Basin

, cattle

ranchers, plantation owners, and small landowners clear the

forest by setting it on fire, which causes an estimated 23–

43% increase in

carbon

dioxide levels worldwide and spreads

smoke

over millions of square miles, which interferes with

air travel and causes respiratory difficulties.

Unfortunately, cleared forest that is turned into pasture

land provides very poor quality soil, which can only be

ranched for a few years before the land becomes infertile

and has to be abandoned. Eventually

desertification

sets

1169

in, causing cattle ranchers to move on to new areas of the

forest.

While huge timber and multi-national corporations

have justifiably received much of the blame for the destruc-

tion of TRFs, local people also play a major role. Populations

of the

Third World

gather wood for heating and cooking,

and the demand brought about by their growing numbers

has resulted in many deforested areas. The proliferation

of coca farms, producing cocaine mainly for the American

market, has also caused significant deforestation and

pollu-

tion

, as has gold prospecting in the Amazon.

The destruction of TRFs has already had devastating

effects on

indigenous peoples

in tropical regions. Entire

tribes, societies, and cultures have been displaced by environ-

mental damage caused by deforestation. In Brazil fewer than

200,000 Indians remain, compared to a population of some

six million about 400 years ago. Sometimes they are killed

outright when they come into contact with settlers, loggers,

or prospectors, either by disease or because they are shot.

And those who are not killed are often herded into miserable

reservations or become landless peasants working for slave

labor wages.

Today, less than 5% of the world’s remaining TRFs

have some type of protective status, and there is often little

or no enforcement of prohibitions against logging,

hunting

,

and other destructive activities.

The ancient rain forests of North America are also

important ecosystems, composed in large part of trees that

are hundreds and even thousands of years old. Temperate

rain forests (or evergreen forests) are usually composed of

conifers (needle-leafed, cone-bearing plants) or broadleaf

evergreen trees. They thrive in cool coastal climates with

mild winters and heavy rainfall and are found along the

coasts of the Pacific Northwest area of North America,

southern Chile, western New Zealand, and southeast

Aus-

tralia

, as well as on the lower mountain slopes of western

North America, Europe, and Asia.

The rain forest of the Pacific Northwest, the largest

coniferous forest

in the world, stretches over 112,000 mi

2

(129,000 km

2

) of coast from Alaska to northern California,

and parts extend east into mountain valleys. The forests of

the Pacific Northwest consist of several species of coniferous

trees, including varieties of spruce, cedar, pine, Douglas fir,

Hemlock, and Pacific yew. Broadleaf trees, such as Oregon

oak, tanoak, and madrone, are also found there. Redwood

tree growth extends to central California. Further south are

the giant sequoias, the largest living organisms on earth,

some of which are over 3,000 years old.

In some ways, the temperate rain forests of the Pacific

Northwest may be the most biologically rich in the world.

Although TRFs contain many more species, temperate rain

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rain forest

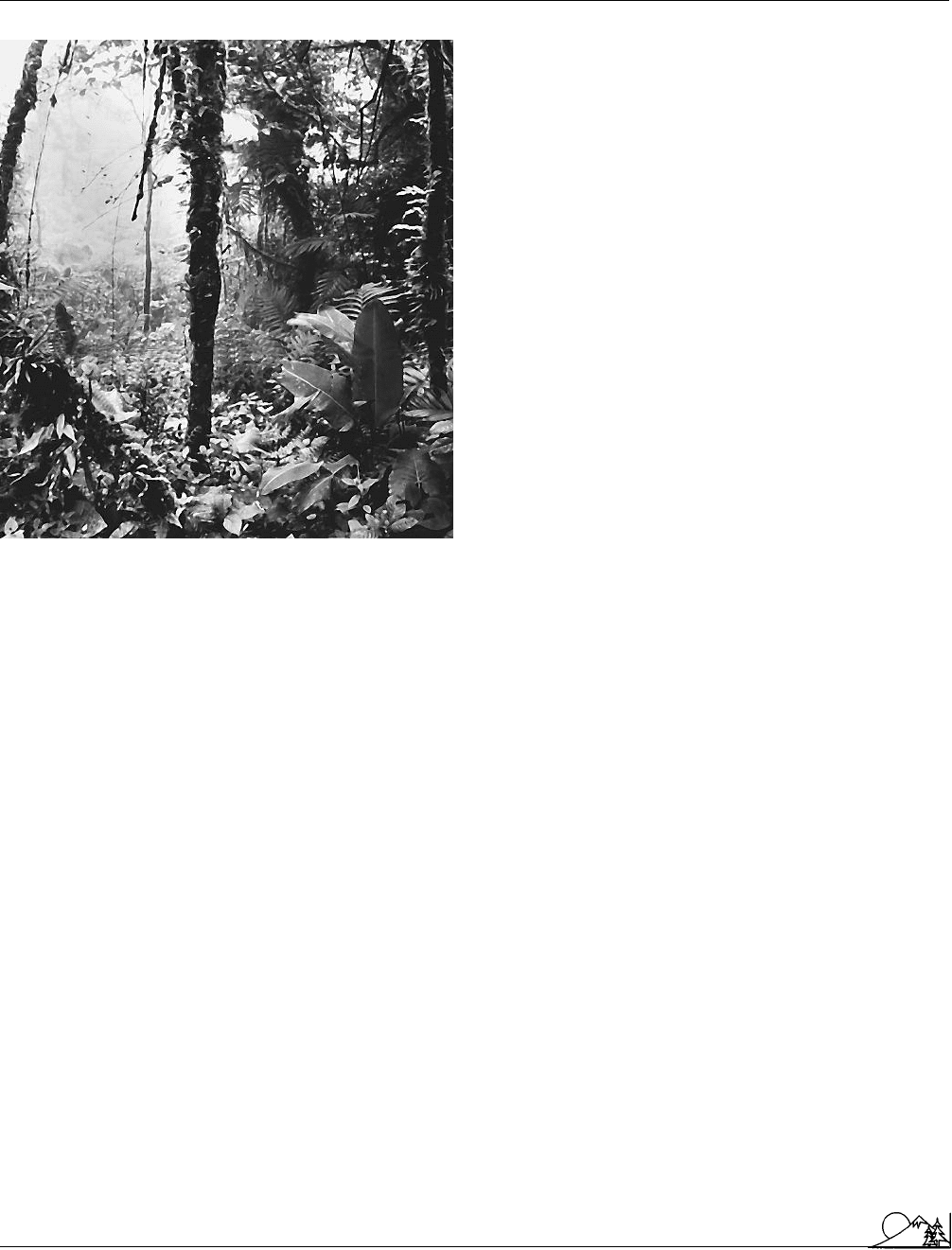

Rain forest. (Photograph by David Julian. Phototake

NYC. Reproduced by permission.)

forests have far more plant matter per acre and contain the

tallest and oldest trees on Earth. Over 210 species of fish

and

wildlife

live in ancient forests, and a single tree can

support over 100 different species of plants. One tree found

in cool, moist forests is the slow-growing Pacific yew, whose

bark and needles contain taxol, considered one of the most

powerful anti-cancer drugs ever discovered.

Unfortunately, the

clear-cutting

of most of the an-

cient forests and their yew trees has caused a serious shortage

of taxol. Some yew trees are unavailable for harvesting be-

cause they grow in forests protected as habitat for the endan-

gered

northern spotted owl

. The logging of federal land

under the jurisdiction of the

Bureau of Land Management

(BLM) and the U.S.

Forest Service

(USFS) has eliminated

some of the last and best habitats for the Pacific yew.

The remaining ancient forest, almost all of which is

now on BLM and USFS land, is being cut at a rate of

200,000 acres (81,000 ha) a year, as of 1992. At this rate it

will be destroyed within less than two decades. The conse-

quences of this destruction will include the disappearance

of

rare species

dependent on this habitat, the silting of

waterways and erosion of soil, and the decimation of

salmon

populations, which provide the world’s richest salmon fish-

ery, worth billions of dollars annually.

1170

Although the timber industry claims that logging

maintains jobs in the Pacific Northwest, logging

national

forest

often makes no economic sense. Because of the ex-

pense of building logging roads, surveying the area to be

cut, and the low price it charges for trees, the USFS often

loses money on its timber sales. As a result of such “deficit”

or “below cost” timber sales between 1989 and 1992, the

USFS lost an average of almost $300 million a year by selling

timber from national forests.

Several private

conservation

groups, such as the

Wil-

derness Society

and the

Sierra Club

, are working to pre-

serve the remaining ancient forests on BLM and USFS land

through federal legislation, lawsuits, and other actions. In

April 1993, President Bill Clinton attended a “timber sum-

mit” in Portland, Oregon, to discuss the ancient forests,

endangered species

, and timber jobs. But the cutting of old

growth forests and “below cost” timber sales have continued

much as before. The Bush administration has not supported

environmental issues. In 2001, President Bush triggered in-

ternational outrage when he refused to agree to the Kyoto

Protocol, a United Nations approved plan to preserve the

environment

.

Two of the largest remaining temperate rainforests are

Alaska’s 16.9 million-acre (6.8 million ha) Tongass National

Forest and the Russian

Taiga

. Tongass is the last large,

relatively undisturbed, temperate rain forest in the United

States, stretching over 600 mi (966 km) of coast along the

Alaska Panhandle. It has the highest concentration of bald

eagles and grizzly bears anywhere on Earth. In addition to

reducing habitat for wildlife and salmon hatching, scenic

areas are being destroyed, reducing tourism and

recreation

in the area.

The huge forests in the Russian Far East and Siberia

are called the Taiga. The Siberian portion is the world’s

largest forest. Comprising some two million mi

2

(5.1 million

km

2

), the Taiga is much larger than the Brazilian Amazon

and would cover the entire American lower 48 states. With

Russia becoming more market-oriented and in desperate

need of money, some have discussed selling the logging

rights to some of these forests to American, Japanese, and

Korean logging companies.

Pressure from environmentalists and increasing public

concern for rain forests has encouraged world leaders to

consider more environmental laws. In June 1992, at the

United Nations Earth Summit

conference in Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil, a set of voluntary principles to conserve the world’s

threatened forests were agreed upon. The document affirms

the right of countries to economically exploit forests but

states that this should be done “on a sustainable basis,”

recognizing the value of forests in absorbing carbon dioxide

and slowing climate change. Initial hope that the agreement

on principles might eventually be turned into a binding

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rainforest Action Network

international convention has evaporated, and throughout the

world, forests continue to be destroyed. Some of the last

remaining untouched forests are being opened up to

poach-

ing

, logging, and other exploitation, such as the one million

acre (405,000 ha) virgin Ndoke rainforest of the northern

Congo Republic, a wildlife paradise full of thousand-year-

old trees, along with

elephants

, leopards, gorillas, and other

endangered species.

There is a small but positive sign of a much-needed

change. In October 2001 Brazil suspended all trade in ma-

hogany. The government’s decision followed a two-year in-

vestigation by

Greenpeace

using ground, air, and satellite

surveillance to document rampant illegal logging on Indian

reservations and other protected wildlife areas. In addition,

a report released in June 2002 showed that the rate of forest

destruction of Brazil’s Amazon jungle fell 13.4% from a five-

year peak in 2000. However, the rate of destruction still

deeply troubles environmentalists. See also Compaction; De-

ciduous forest; Decomposition; Migration; Old-growth

forest

[Bill Asenjo Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Caufield, C. In the Rainforest: Report From a Strange, Beautiful, Imperiled

World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Mitchell, G. J. World on Fire: Saving an Endangered Earth. New York:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1991.

Myers, N. The Sinking Ark: A New Look at Disappearing Species. Oxford:

Pergamon Press, 1979.

Porritt, J. Save the Earth. Atlanta: Turner Publishing, 1991.

Raven, P. H. “The Cause and Impact of Deforestation.” In Earth 88:

Changing Geographic Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Geographic

Society, 1988.

Repetto, R. The Forest for the Trees? Government Policies and the Misuse of

Resources. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 1988.

Zuckerman, S. Saving Our Ancient Forest. Los Angeles: Living Planet

Press, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

Bugge, A. “Brazil’s Amazon Destruction Down but Still Alarming.” Reuters

June 12, 2002.

Jordan, M. “Brazilian Mahogany: Too Much In Demand—Illegal Logging,

Exports Are Lucrative for Criminals, Disastrous for Rain Forest.” Wall

Street Journal, November 14, 2001.

“United States Government Report Blames Humans for Global Warming.”

Reuters [cited July 2002]. <http://www.enn.com/news/wirestories/2002/06/

06042002>.

“World Bank Forest Policy.” World Rainforest Movement Bulletin 55 [cited

February 2002]. <http://www.wrm.org.uy>.

1171

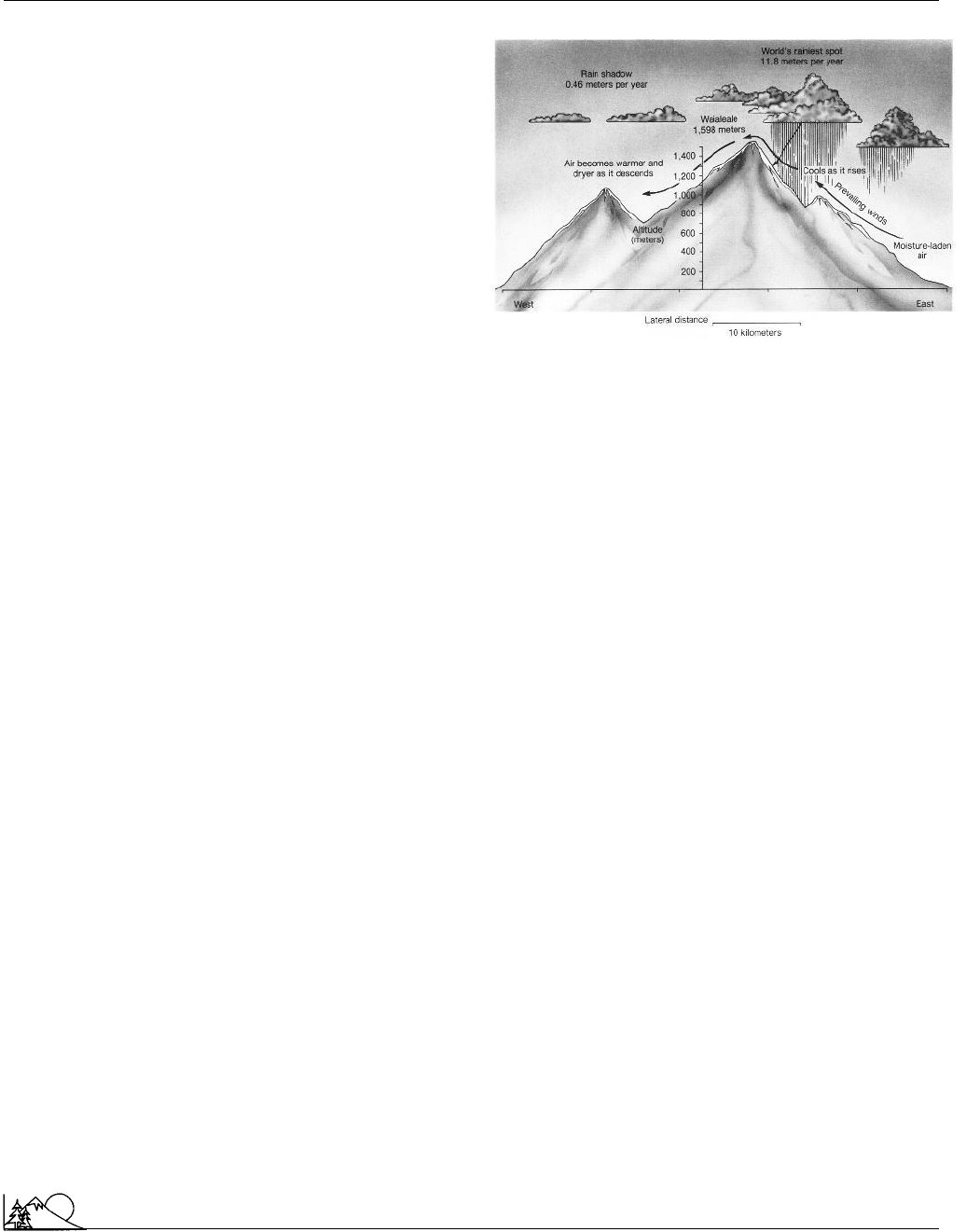

A rain shadow in Hawaii on the eastern side

of Mount Waialeale. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced

by permission.)

Rain shadow

A region of relative dryness found on the downwind side of

a mountain range or other upland area. As an air mass rises

over the upwind side of a mountain range, pressure drops

and temperature falls. This causes the relative humidity of

the air mass to rise. Eventually the moisture in the air con-

denses and precipitation occurs. An air mass that is now

cooler and drier passes over the top of the mountain range.

As it descends on the downwind side of the range, it warms

again and its relative humidity is further reduced. This reduc-

tion in relative humidity not only prevents further rainfall,

but also causes the air mass to absorb moisture from other

sources, drying the

climate

on the downwind side. The

ultimate result is lush forest on the windward side of a

mountain separated by the summit from an

arid environ-

ment

on the downwind side. Examples of rain shadows

include the arid areas on the eastern sides of the mountain

ranges of western North America, and the Atacama

Desert

in Chile on the downwind side of the Andes Mountains.

Rainforest Action Network

Rainforest Action Network (RAN), founded in 1985, is an

activist group that works to protect rain forests and their

inhabitants worldwide. Its strategy includes imposing public

pressure on those corporations, agencies, nations, and politi-

cians whom the group believes are responsible for the de-

struction of the world’s rain forests by organizing letter-

writing campaigns and consumer boycotts. In addition to

mobilizing consumer and environmental groups in the

United States, RAN organizes and supports conservationists

committed to

rain forest

protection around the world.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rangelands

RAN’s first direct action campaign was the boycott of

Burger King. The fast-food restaurant chain was importing

much of its beef from Central and South America, where

large areas of forests have been turned into pastureland for

cattle. RAN contends that “after sales dropped 12% during

the boycott in 1987, Burger King canceled $35 million worth

of beef contracts in Central America and announced that it

had stopped importing rainforest beef...The formation of

Rainforest Action Groups (RAGs) that staged demonstra-

tions and held letter-writing parties in U.S. cities helped

make the boycott and other campaigns a success.” RAN

states that there are now over 150 RAGs in North

America alone.

RAN also works with human rights groups around

the world, attempting to protect and save the cultures of

indigenous peoples

dependent on rain forests. The group

helps support ecologically sustainable ways to use the rain

forest, such as

rubber

tapping and the harvesting of such

foods as nuts and fruits.

RAN urges the public to avoid buying tropical wood,

such as rosewood and mahogany, and plywood made from

rain forest

timber. The group also recommends that people

not buy rainforest beef, which is often found in fast-food

hamburgers and processed beef products.

RAN is strongly pushing its boycott of the Japanese

conglomerate Mitsubishi, which makes televisions, VCRs,

fax machines, and stereos. RAN points out that “Mitsubishi

has big

logging

operations in Malaysia, Borneo, Philippines,

Indonesia, Chile, Canada, and Brazil...It is the world’s num-

ber one importer of tropical timber.” Other corporations

that RAN has criticized for damaging rain forests include

ARCO, Scott Paper, Coca-Cola, Texaco, and CONOCO,

as well as such international agencies as the

World Bank

and

the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO).

RAN operates an extensive media campaign targeted

at companies and decision-makers who create policy on

rainforests by running full-page advertisements in such major

newspapers as The New York Times and the Wall Street

Journal, RAN’s publications include its quarterly World

Rainforest Report; its monthly Action Alerts; The Rainforest

Action Guide; and The Rainforest Catalogue, offering books,

videos, bumper stickers, T-shirts, and other products pro-

moting rainforest protection, as well as cosmetics and food

made from rain forest plants.

Among the victories achieved by or with the help of

RAN are the halting of a plan to cut down the one-million-

acre (404,687-ha) La Mosquito Forest in Honduras—made

famous by the movie The Mosquito Coast—which is essential

to the cultures and livelihoods of some 35,000 indigenous

people; forcing the World Bank to stop making loans to

nations that destroy their rain forests; stopping

oil drilling

in the Ecuadorian Amazon by CONOCO and Du Pont;

1172

preventing the opening of a major road to take timber out

of the Amazon to the Pacific Coast; and persuading Coca-

Cola to donate land in Belize for a

nature

preserve.

Nevertheless, the destruction of the world’s rain forests

continues on an enormous scale. As RAN’s director Randall

Hayes points out: “Over 50 percent of the world’s tropical

rainforests are gone forever. Two-thirds of the southeast

Asia forests have disappeared, mostly for hardwood shipped

to Japan, Europe, and the U.S. And this destruction contin-

ues at a rate of 150 acres per minute, or a football field per

second.”

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Rainforest Action Network. 221 Pine Street, Suite 500, San Francisco,

CA USA 94104 (415) 398-4404, Fax: (415) 398-2732, Email:

rainforest@ran.org, <http://www.ran.org>

Ramsar Convention

see

Convention on Wetlands of

International Importance (1971)

Rangelands

Concentrated in 16 western states, rangelands comprise 770

million acres (311.6 million ha) and over one-third of the

land base in the United States. Rangelands are vegetated

predominately by shrubs, and they include

grasslands

,

tun-

dra

, marsh, meadow,

savanna

,

desert

, and alpine commu-

nities. They are fragile ecosystems that depend on a complex

interaction of plant and animal

species

with limited re-

sources, and many range areas have been severely damaged

by

overgrazing

. Currently over 300 million acres (121 mil-

lion ha) within the United States alone are classified as

being in need of

conservation

treatment and management.

Effective range-management techniques include

soil con-

servation

, preservation of

wildlife habitat

, and protection

of watersheds.

Raphus cucullatus

see

Dodo

Raprenox (nitrogen scrubbing)

A recently-developed technique for removing

nitrogen ox-

ides

from waste gases makes use of a common, nontoxic

organic compound known as cyanuric

acid

,C

3

H

3

N

3

O

3

.

When heated to temperatures of about 660°F (345°C), cya-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Reclamation

nuric acid decomposes to form isocyanic acid. The acid, in

turn, reacts with oxides of

nitrogen

to form

carbon diox-

ide

,

carbon monoxide

, nitrogen, and water. The process

has been given the name of raprenox, which comes from the

expression rapid removal of nitrogen oxides. In tests so far,

the method has worked very well with internal

combustion

engines, removing up to 99% of all nitrogen oxides from

exhaust gases. Its efficiency with gases released from smoke-

stacks has not yet been determined. See also Scrubbers

Rare species

A

species

that is uncommon, few in number, or not abun-

dant. A species can be rare and not necessarily be endangered

or threatened, for example, an organism found only on an

island or one that is naturally low in numbers because of a

restricted range. Such species are, however, usually vulnera-

ble to any exploitation, interference, or disturbance of their

habitats. Species may also be common in some areas but

rare in others, such as at the edge of its natural range.

“Rare” is also a designation that the IUCN—The

World Conservation Union gives to certain species “with

small world populations that are not at present ‘endangered’

or ‘vulnerable’ but are at risk. These species are usually local-

ized within restricted geographical areas or habitats or are

thinly scattered over a more extensive range.” Some Ameri-

can states have also employed this category in protective

legislation.

RDFs

see

Refuse-derived fuels

Recharge zone

The area in which water enters an

aquifer

. In a recharge

zone surface water or precipitation percolate through rela-

tively porous, unconsolidated, or fractured materials, such

as sand, moraine deposits, or cracked basalt, that lie over a

water bearing, or aquifer, formation. In some cases recharge

occurs where the water bearing formation itself encounters

the ground surface and precipitation or surface water seeps

directly into the aquifer. Recharge zones most often lie in

topographically elevated areas where the

water table

lies

at some depth. Aquifer recharge can also occur locally where

streams or lakes, especially temporary ponds, are fed by

precipitation and lie above an aquifer. Karst

sinkholes

also

frequently serve as recharge conduits. A recharge zone can

extend hundreds of square miles, or it can occupy only a

small area, depending upon geology, rainfall, and surface

topography

over the aquifer. Recharge rates in an aquifer

1173

depend upon the amount of local precipitation, the ability

of surface deposits to allow water to filter through, and the

rate at which water moves through the aquifer. Water moves

through the porous rock of an aquifer sometimes a few

centimeters a day and sometimes, as in karst limestone re-

gions, many kilometers in a day. Surface water can enter an

aquifer only as fast as water within the aquifer moves away

from the recharge zone.

Because recharge zones are the water intake for exten-

sive underground reservoirs, they can easily be a source of

groundwater

contamination. Agricultural pesticides and

fertilizers are especially common groundwater pollutants.

Applied year after year and washed downward by rainfall

and

irrigation

water,

agricultural chemicals

frequently

percolate into aquifers and then spread through the local

groundwater system. Equally serious are contaminants

leaching

from

solid waste

dumps. Rainwater percolating

through

household waste

picks up dozens of different

organic and inorganic compounds, and contamination ap-

pears to continue a long time: pollutants have recently been

found leaching from waste dumps left by the Romans almost

2,000 years ago. Perhaps most serious are

petroleum

prod-

ucts, including

automobile

oil, which Americans dump or

bury in their back yards at the rate of 240 million gal (910

million l) per year, or 4.5 million gal (18 million l) each

week. On a more industrial scale, inadequately sealed toxic

waste and radioactive materials contaminate extensive areas

of groundwater when they are deposited near recharge zones.

Because recharge occurs in a vast range of geologic condi-

tions, all these contamination sources present real threats to

groundwater quality. See also Hazardous waste; Radioac-

tive waste

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Fetter, C. W. Applied Hydrology. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill, 1980.

Freeze, R. A., and J. A. Cherry. Groundwater. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 1979.

Reclamation

This term has been used environmentally in two distinct

ways. The more historic use refers to making land productive

for agriculture. The current usage refers mostly to the resto-

ration of disturbed land to an ecologically stable condition.

The main application for agricultural purposes is the

development of

irrigation

. That was the mission given in

1902 to the federal

Bureau of Reclamation

under the

U.S.

Department of Agriculture

. This agency has built a total

of 180 water projects in 17 western states, including the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Reclamation

Hoover and Glen Canyon

Dams

in Arizona, and supplies

10 trillion gal (37.8 trillion l) of water to 31 million people

every year. However, this type of reclamation has led to

much environmental damage and now scientists are trying

to figure out how to reverse this damage. The term reclama-

tion has also been used to describe the system of dikes and

pumps in the Netherlands to allow farming of lands below

sea level.

The main thrust of reclamation today is the restoration

of land damaged by human activity, especially by

strip min-

ing

for

coal

. Surface or strip mining represented a third of

coal production in 1963, increasing to 60% in 1973. This

increase in production led to more damage to the land and

once the environmental impact was realized, the reclamation

movement began. Since 1970, over two million acres

(800,000 ha) of mined lands have been restored, plus 100,000

acres (40,500 ha) of abandoned mines.

However, it wasn’t until 1977 that Congress finally

passed the landmark legislation, the

Surface Mining Control

and Reclamation Act

. Earlier attempts had failed because

of the perceived threat to jobs. This act applies only to coal

mining and restricts mining in prime western farmlands or

where owners of surface rights object. The act requires mine

operators to 1) demonstrate reclamation proficiency; 2) re-

store the shape of the land to the original contour and

revegetate it if requested by the landowner; 3) minimize

impacts on the local

watershed

and

groundwater

and

prevent

acid

contamination; and 4) pay a fee on each ton

of coal mined into a $4.1 billion fund to reclaim orphaned

lands left by earlier mining.

Since the act was passed, it has come under fire by

both industry and environmentalists, resulting in more than

50 amendments. During the Carter administration, excessive

litigation caused many delays to implementing and enforcing

the regulations. When Reagan was in office, 60% of the

regulations were reviewed or eliminated. The

Office of Sur-

face Mining

Reclamation and Enforcement came under

attack during the first Bush administration because of its

lack of performance in enforcing the legislation. During this

time 6,000 mines were abandoned without reclamation and

there were many exemptions from regulations.

In 1995, several amendments were proposed to mini-

mize the duplication of state and federal regulations. A 1997

report by the Public Employees for Environmental Respon-

sibility claimed that continued lack of enforcement led to

less than one percent of the 120,000 acres (48,500 ha) strip

mined in Colorado and not one acre of over 90,000 acres

(36,000 ha) of stripped Indian lands being reclaimed as of

1996. During the second Bush administration, new regula-

tions governing mining on federal lands were established in

2001, which environmentalists claimed would reinstate

1174

dated reclamation standards that led to

pollution

of land

and water.

Another type of strip mining, mountaintop removal,

has recently come under attack for violating the reclamation

legislation. This method involves using machinery to cut off

entire mountaintops, as much as 400 ft (122 m), to reach

the coal underneath. The rock and earth removed from these

mountaintops are dumped into nearby streams in waste piles

called valley fills. Environmentalists believe many streams

are being destroyed; in West Virginia alone over 1,000 mi

(1600 km) of streams have been buried. These mines violate

the conditions for

buffer

zone variances (no mining activities

can take place within a 100-ft (30-m) buffer zone near

streams, unless environmental conditions are satisfied.) An-

other federal court ruling in 1999 said that valley fills also

violated the

Clean Water Act

. For some mine operators

who claim their sites will be used for grazing or

wildlife

habitat

, improper reclamation methods prevent the sites

from being used for this purpose.

Reclamation clearly adds to the cost of coal. For Appa-

lachian coal this reaches 15% of the cost per

Btu

(British

Thermal Unit). The 1977 act created a level playing field

where all compete under the same rules. Costs easily involve

$1,000–$5,000 per acre, but this is small compared to royal-

ties paid the landowner. In Germany, where coal seams are

very thick and land values are at a premium because of heavy

population pressure, great efforts are made to reclaim the

land, even up to $10,000 per acre. In terms of productive

farm, grazing, or timber lands, restoration after a one-time

extraction of coal allows a return to

sustainable agriculture

or forestry.

Strip mining creates four landforms which the recla-

mation process must address: rows of

spoil

banks, final cut

canyons, high walls adjacent to the final cut, and coal-haul

roads. The first two are relatively easy, but the latter two

require special treatment. Reshaping the land to the original

contour and keeping the

soil

in place are major challenges

in hilly terrain. Operators usually find it necessary to cut

into the unmined hillside to make it grade into the mined

land below.

Subsidence

of

overburden

could conceivably

create a cliff face along the headwall if not adequately com-

pacted. Minimizing grading during the mining process is

one way to minimize the amount of land excavation and

alteration.

When possible, natural looking slopes can be achieved

during the mining process by mining to the prescribed safety

angles, or by the cut and fill method. This is generally

the most inexpensive means of reclamation. Before mining,

topography

maps should be made of existing slopes and

contours so that mining can match these as close as possible.

Besides physically reshaping the land, for reclamation

to succeed the essential needs of

erosion

control,

topsoil

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Reclamation

replacement, and nurturing and protecting young vegetation

until it can survive on its own must be met. These needs

are interdependent. Vegetation is crucial for erosion control,

especially as the slope gradient increases; however vegetation

struggles without topsoil, critical nutrients, and protection

from wildlife and livestock. One additional problem,

acid

mine drainage

, is eliminated by good reclamation, as the

oxidizing materials which produce the acid are buried.

Coal-haul roads are very dense from the heavy vehicles

traversing them. They must be ripped up and plowed for

even minimal revegetation success or, less desirable, be bur-

ied under overburden. Such access roads can cause the big-

gest disturbance to sites since they must be designed to meet

roadway standards. These roads should thus be designed to

minimize grading and require careful planning.

The one most crucial element, and most expensive, is

topsoil replacement. Earthwork (backfilling and grading)

accounts for up to 90% of reclamation costs. Original soils

provide five major benefits: 1) a seedbed with the physical

properties needed for survival; 2) a

reservoir

for needed

nutrients; 3) a superior medium for water

absorption

and

retention; 4) a source of native seeds and plants; and 5) an

ecosystem

where the decomposer and aerator-mixer organ-

isms can thrive. The absence of even one of these categories

often dooms reclamation efforts.

The more one studies this problem, the more impor-

tant the topsoil becomes; truly it is one of the earth’s most

vital resources. Loose overburden is sometimes so coarse and

lacking in nutrients that it can support little plant cover. A

quick buildup of

biomass

is critical for erosion control, but

without the topsoil to sustain both plant productivity and

the

microorganisms

needed to decompose the dead bio-

mass, any ground cover is soon lost, exposing the soil to

increasingly higher erosion rates.

Some areas, such as flat lowlands, can revegetate with

or without human aid. But for many lands, especially those

with large fractures of rock and air voids, reclamation is

practically an all or nothing venture, with little tolerance for

halfway measures. Indeed, in conditions where most of the

negative impacts are retained within the site, reclamation

may easily worsen conditions by removing the barriers to

runoff

and

sediment

.

Stabilization of the site may also be needed to complete

the mining and reclamation process. Methods include exten-

sive grading, slope alteration, hazard removal, and soil stabi-

lization. The latter method increases the load

carrying ca-

pacity

of soils and can be achieved by using reinforced earth

or a chemical treatment. The ability to handle runoff and

precipitation is improved. Runoff can also be reduced by

planting vegetation on top of the slope or cut.

Much of what is needed for effective reclamation is

known. What has been missing has been the will to do it

1175

and the legal clout for enforcement. A new approach holds

promise to increase this willingness to reclaim the land,

which is based on the emerging field of eco-asset manage-

ment. Ecological resources such as forests and

wetlands

are developed and treated as financial assets to their owner.

This market-based approach results in higher quality recla-

mation, an increase in the number of sites reclaimed, and

economic benefits to property owners and other participants.

Hopefully, such an approach will help persuade the mining

industry that reclamation is an investment in the future. See

also Mine spoil waste; Restoration ecology

[Laurel M. Sheppard]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bradshaw, A. D., and M. J. Chadwick. The Restoration of Land: The Ecology

and Reclamation of Derelict and Degraded Land. Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1980.

Law, D. L. Mined-Land Rehabilitation. New York: Van Nostrand Rein-

hold, 1984.

Meleen, N. H. Geomorphological Perspectives on Land Disturbance and Recla-

mation. Oxford Polytechnic Discussion Papers in Geography, No. 22. Ox-

ford, England: Oxford Polytechnic, 1986.

Powell, J. W. “The Reclamation Idea.” In American Environmentalism:

Readings in Conservation History, edited by R. F. Nash. 3rd ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1990.

The Practical Guide to Reclamation in Utah. Division of Oil, Gas & Mining,

State of Utah, Department of Natural Resources, 2001.

Williams, R. D., and G. E. Schuman, eds. Reclaiming Mine Soils and

Overburden in the Western United States: Analytic Parameters and Procedures.

Ankeny, IA: Soil Conservation Society of America, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

Barnard, J. “Has the Bureau of Reclamation Met the Needs of the Changing

West?” Associated Press, June 18, 2002.

“Hardrock Mining on Federal Lands.” The National Academy Press, 2000.

Kenworthy, T. “New Mining Rules Reverse Provisions.” USA Today, Octo-

ber 25, 2001.

“Mountain Top Removal Mining Called Illegal.” Environmental News Net-

work 1998 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.enn.com>.

Ward Jr., K. “Lawmaker Offers Mixed Reaction to Strip Mining Ruling.”

Knight-Ridder/Tribune Business News, May 15, 2002.

O

THER

Citizens Coal Council. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.citizencoalscoun-

cil.org>.

Empty Promise. Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, 1997.

Green, E., et al. The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation At of 1977:

New Era of Federal-State Cooperation or Prologue to Future Controversy? 16

E. Min. L. Inst., Chapter 11, 1997.

Narten, P. F., et al. Reclamation of Mined Lands in the Western Coal Region.

U.S. Geological Survey Circular 872. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Geological

Survey, 1983.

Natural Strategies. October 2001 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.naturalstra-

tegies.com/nsn-10-01.htm>.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Record of Decision

Record of Decision

A Record of Decision (ROD) is a public document that

explains which remedial alternatives will be used to clean

up a Superfund site. A Superfund site is a site listed on the

National Priorities List

(NPL), which identifies sites in the

United States that pose the greatest long term threat to

human health and the

environment

. Placement on the NPL

means that clean up of the site must follow the requirements

of the

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Com-

pensation, and Liability Act

, which outlines the process

for completing site clean up.

The first step in the process is to conduct a Remedial

Investigation and Feasibility Study (RI/FS). During the RI,

data are collected to characterize site conditions, determine

the nature of the wastes, assess risk to human health and

the environment, and conduct treatability studies to evaluate

the potential performance and cost of treatment technologies

being considered. The FS is the mechanism used to develop,

screen and evaluate alternative remedial actions. A result of

the RI/FS is the development of the Proposed Plan, which is

the identification of a recommended remedy. The preferred

remedy is one that will be effective over both the short

and long-term, reduce toxicity, mobility and/or volume of

contamination, be technically and economically feasible to

implement, and be acceptable to the state and the commu-

nity. After a period for public comment on the RI/FS and

the Proposed Plan, the ROD is prepared. The ROD has

three basic components: (1) the Declaration, which is an

abstract and data certification sheet for the key information

in the ROD and is the formal authorizing signature page;

(2) the Decision Summary, which provides an overview of

site characteristics, alternatives evaluated, and the analysis

of those options; it also identifies the selected remedy and

explains how the remedy fulfills statutory and regulatory

requirements; and (3) the Responsiveness Summary, which

presents stakeholder concerns that were obtained during

the public comment period about the site and preferences

regarding the remedial alternatives. The Summary also ex-

plains how those concerns were addressed and how the pref-

erences were factored into the remedy selection process.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. A Guide to Preparing Superfund

Proposed Plans, Records of Decision, and other Remedy Selection Decision

Documents. EPA 540-R-98-031. Washington, DC: Office of Solid Waste

and Emergency Response, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1999.

1176

O

THER

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Superfund Cleanup Process. March

28, 2001 [cited June 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/superfund/action/pro-

cess/sfproces.htm>.

Recreation

The term recreation comes from the Latin word recreatio,

referring to refreshment, restoration, or recovery. The mod-

ern notion of recreation is complex, and many definitions

have been suggested to capture its meaning. In general, the

term recreation carries the idea of purpose, usually restora-

tion of the body, mind, or spirit. Modern definitions of

recreation often include the following elements: 1) it is an

activity rather than idleness or rest, 2) the choice of activity

or involvement is voluntary, 3) recreation is prompted by

internal motivation to achieve personal satisfaction, and 4)

whether an activity is recreation is dependent on the individ-

ual’s feelings or attitudes about the activity.

The terms “leisure” and “play” are often confused with

recreation. Recreation is one kind of leisure, but only part

of the expressive activity is leisure. Leisure may also include

non-recreational pursuits such as religion, education, or

community service. Although play and recreation overlap,

play is not so much an activity as a form of behavior, charac-

terized by make-believe,

competition

, or exploration. More-

over, whereas recreation is usually thought of as a purposeful

and constructive activity, play may not be goal-oriented and

in some cases may be negative and self-destructive.

The benefits of recreation include producing feelings

of relaxation or excitement and enhancing self-reliance,

mental health, and life-satisfaction. Societal benefits also

result from recreation. Recreation can contribute to im-

proved public health, increased community involvement,

civic pride, and social unity. It may strengthen family struc-

tures, decrease crime, and enhance

rehabilitation

of individ-

uals. Outdoor recreation promotes interest in protecting our

environment

and has played an important educational role.

However, recreational activities have also damaged the envi-

ronment. Edward Abbey, among others, have decried the

tendency of industrial tourism to destroy wild areas and ani-

mal habitats. For example, some cite the damming of wild

rivers to create lakes for boating and skiing or defacing

mountain sides for ski runs and ski lifts as putting human

recreation over environment.

Recreation is big business, creating jobs and economic

vitality. In 2001 American consumers spent $100 billion on

recreation and leisure activities. Much of these expenditures

are for wildlife-related recreation. In 2001, more than 80

million Americans age 16 or older enjoyed some sort of

recreation related to

wildlife

like fishing,

hunting

, bird-

watching, or wildlife photography. More than 13 million