Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sanitation

stomach upsets, there is a risk of life-threatening diseases

such as

cholera

, dysentery, and hepatitis. Ssos are a major

cause of beach closures. In 2000, an Sso discharged an esti-

mated 72 million gal (273 million l) of raw sewage into the

Indian River, causing drinking-water advisories and beach

closures throughout much of Florida. Sewage contamination

can rob water of oxygen and result in floating debris and

harmful blooms of algae. Sewage from Ssos can destroy

habitat

and harm plants and animals.

Ssos often occur when excess rainfall or snowmelt in

the ground enters leaky sanitary sewers that were not built

to hold rainfall or which do not drain properly. Excess water

also can enter sewers from roof drains that are connected to

sewers, through broken pipes, or through poorly connected

service lines. In some cities, as many as 60% of Ssos originate

at service connections to buildings. Sometimes new subdivi-

sions or commercial buildings are connected to systems that

are too small. Ssos also can occur when pipes crack, break,

or become blocked by tree roots or debris.

Sediment

, debris,

oil, and grease can build up in pipes, causing them to break

or collapse. Sometimes pipes settle or shift so that the joints

no longer match. Pump or power failures also can cause

Ssos. Many sewer systems in the United States are 30–100

years old and the EPA estimates that about 75% of all

systems have deteriorated to where they carry only 50% or

less of their original capacity. Ssos are also caused by im-

proper installation or maintenance of the system and by

operational errors. Some municipalities have had to spend

as much as a billion dollars correcting sewer problems or

have halted new development until the system is fixed or its

capacity increased.

Most Ssos are avoidable. Cleaning, maintenance, and

repair of systems, enlarging or upgrading sewers, pump sta-

tions, or treatment plants, building wet-weather storage and

treatment facilities, or improving operational procedures may

be necessary to prevent Ssos. In some cases backup facilities

may be required. Many municipalities are developing flow-

equalization basins to retain excessive wet-weather flow until

the system can handle it. The EPA estimates that an addi-

tional 12 billion dollars will be required annually until 2020,

if the nation’s sewer systems are to be repaired.

In 1995 representatives from states, municipalities,

health agencies, and environmental groups formed the Sso

Federal Advisory Subcommittee to advise the EPA on Sso

regulations. In May 1999 President Bill Clinton ordered

stronger measures to prevent Ssos that close beaches and

adversely affect

water quality

and public health. Each EPA

region is now required to inventory Sso violations and to

address Ssos in priority sewer systems. In January 2001 the

EPA’s Office of

Wastewater

Management proposed a new

SSO Rule that will expand the Clean Water Act permit

requirements for 19,000 municipal sanitary sewer collection

1247

systems to reduce Ssos. Furthermore, some 4,800 additional

municipal collection systems will be required to obtain per-

mits from the EPA. Both the public and health and commu-

nity officials will have to be notified immediately of raw

sewage overflows that endanger public health.

[Margaret Alic Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Office of Water. Benefits of Protecting Your Community from Sanitary Sewer

Overflows. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Bell Jr., Robert E., and Maggie L. Powell. “Pending SSO Regulations.”

Water Engineering & Management 148, no. 4 (April 2001): 30–37.

Hobbs, David V., Eva V. Tor, and Robert D. Shelton. “Equalizing Wet

Weather Flows.” Civil Engineering 69, no. 1 (January 1999): 56–9.

Whitman, David. “The Sickening Sewer Crisis: Aging Systems Across the

Country are Causing Nasty—and Costly —Problems.” U.S. News & World

Report (June 12, 2000): 16–18.

O

THER

Beach Watch. Frequently Asked Questions. Office of Water, U.S. Environ-

mental Protection Agency. April 16, 1999 [cited May 31, 2002]. <http://

www.epa.gov/ost/beaches/faq.html>.

Liquid Assets 2000: Today’s Challenges. U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency. May 31, 2002 [cited May 31, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/cgi-

bin/epaprintonly.cgi>.

Office of Wastewater Management. Sanitary Sewer Overflows. U.S. Envi-

ronmental Protection Agency. March 14, 2001 [cited May 31, 2002].

<http://www.cfpub.epa.gov/npdes/home.cfm?program_id=4>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

American Public Works Association, 2345 Grand Blvd., Suite 500, Kansas

City, MO USA 64108-2641, (816) 472-6100, <http://www.pubworks.org>

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Wastewater Management,

Mail Code 4201, 401 M Street, SW, Washington, DC, USA 20460

(202) 260-7786, Fax: (202) 260-6257, <http://www.epa.gov/owm/sso>

Sanitation

Sanitation can be defined as the measures, methods, and

activities that prevent the transmission of diseases and ensure

public health. Specifically, “sanitation” refers to the hygienic

principles and practices relating to the safe collection, re-

moval and disposal of human excreta, refuse, and

waste-

water

.

For a household, sanitation refers to the provision and

ongoing operation and maintenance of a safe and easily

accessible means of disposing of human excreta,

garbage

,

and wastewater, and providing an effective barrier against

excreta-related diseases.

The problems that result from inadequate sanitation

can be illustrated by the following events in history:

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sanitation

1700

B.C.

: Ahead of his time by a few thousand years,

King Minos of Crete had running water in his bathrooms

in his palace at Knossos. Although there is evidence of

plumbing and sewerage systems at several ancient sites, in-

cluding the cloaca maxima (or great sewer) of ancient Rome,

their use did not become widespread until modern times.

1817: A major epidemic of

cholera

hit Calcutta, India,

after a national festival. There is no record of exactly how

many people were affected, but there were 10,000 fatalities

among British troops alone. The epidemic then spread to

other countries and arrived in the United States and Canada

in 1832. The governor of New York quarantined the Cana-

dian border in a vain attempt to stop the epidemic. When

cholera reached New York City, people were so frightened,

they either fled or stayed inside, leaving the city streets

deserted.

1854: A London physician, Dr. John Snow, demon-

strated that cholera deaths in an area of the city could all

be traced to a common public drinking water pump that was

contaminated with sewage from a nearby house. Although he

could not identify the exact cause, he did convince authorities

to close the pump.

1859: The British Parliament was suspended during

the summer because of the stench coming from the Thames.

As was the case in many cities at this time, storm sewers

carried a combination of sewage, street debris, and other

wastes, and storm water to the nearest body of water. Ac-

cording to one account, the river began to “seethe and fer-

ment under a burning sun.”

1892: The comma-shaped bacteria that causes cholera

was identified by German scientist, Robert Loch, during an

epidemic in Hamburg. His discovery proved the relationship

between contaminated water and the disease.

1939: Sixty people died in an outbreak of typhoid fever

at Manteno State Hospital in Illinois. The cause was traced

to a sewer line passing too close to the hospital’s water

supply.

1940: A valve that was accidentally opened caused

polluted water from the Genesee River to be pumped into

the Rochester, New York, public water supply system. About

35,000 cases of gastroenteritis and six cases of typhoid fever

were reported.

1955: Water containing a large amount of sewage was

blamed for overwhelming a

water treatment

plant and

causing an epidemic of hepatitis in Delhi, India. An esti-

mated one million people were infected.

1961: A worldwide epidemic of cholera began in Indo-

nesia and spread to eastern Asia and India by 1964; Russia,

Iran, and Iraq by 1966; Africa by 1970; and Latin America

by 1991.

1248

1968: A four-year epidemic of dysentery began in

Central America resulting in more than 500,000 cases and

at least 20,000 deaths. Epidemic dysentery is currently a

problem in many African nations.

1993: An outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in Milwaukee,

Wisconsin, claimed 104 lives and infected more than

400,000 people, making it the largest recorded outbreak of

waterborne disease in the United States.

The problem of sanitation in developed countries, who

have the luxury of adequate financial and technical resources

is more concerned with the consequences arising from inade-

quate commercial food preparation and the results of bacteria

becoming resistant to disinfection techniques and antibiot-

ics. Flush

toilets

and high quality drinking water supplies

have all but eliminated cholera and epidemic diarrheal dis-

eases. However, in many developing countries, such as the

Pacific islands, inadequate sanitation is still the cause of life

or death struggles.

In 1992, the South Pacific Regional Environment Pro-

gramme (SPREP) and a Land-Based Pollutants Inventory

stated that “[t]he disposal of solid and liquid wastes (particu-

larly of human excrement and household garbage in urban

areas), which have long plagued the Pacific, emerge now as

perhaps the foremost regional environmental problem of the

decade.”

High levels of fecal

coliform bacteria

have been found

in surface and coastal waters. The SPREP Land-Based

Sources of

Marine Pollution

Inventory describes the Feder-

ated States of Micronesia’s sewage

pollution

problems in

striking terms: The prevalence of water-related diseases and

water quality

monitoring data indicate that the sewage

pollutant

loading

to the environment is very high. A recent

waste quality monitoring study (as part of a workshop) was

unable to find a clean, uncontaminated site in the Kolonia,

Pohnpei, area.

Many central wastewater treatment plants constructed

with funds from United States

Environmental Protection

Agency

in Pohnpei and in Chuuk States have failed due to

lack of trained personnel and funding for maintenance.

In addition, septic systems used in some rural areas

are said to be of poor design and construction, while pour-

flush toilets and latrines—which frequently overflow in

heavy rains—are more common. Over-the-water latrines are

found in many coastal areas, as well.

In the Marshall Islands, signs of eutrophication—ex-

cess water plant growth due to too much nutrients—resulting

from sewage disposal are evident next to settlements, particu-

larly urban centers. According to a draft by the Marshall

Islands NEMS, “one-gallon blooms occur along the coast-

line in Majuro and Ebeye, and are especially apparent on the

lagoon

side adjacent to households lacking toilet facilities.”

Stagnation of lagoon waters, reef degradation, and

fish kills

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Santa Barbara oil spill

resulting from the low levels of oxygen have been well docu-

mented over the years. Additionally, red tides

plague

the

lagoon waters adjacent to Majuro.

There is significant

groundwater pollution

in the

Marshall Islands as well. The Marshall Island EPA estimates

that more than 75% of the rural

wells

tested are contami-

nated with fecal coliform and other bacteria. Cholera, ty-

phoid and various diarrheal disorders occur.

With very little industry present, most of these prob-

lems are blamed on domestic sewage, with the greatest con-

tamination problems believed to be from pit latrines, septic

tanks, and the complete lack of sanitation facilities for 60%

of rural households. As is often the case, poor design and

inappropriate placement of these systems are often identified

as the cause of contamination problems. In fact, even the

best of these systems in the most favorable

soil

conditions

allow significant amounts of nutrients and pathogens into

the surrounding environment, and the soil characteristics

and high

water table

typically found on atolls significantly

inhibit treatment. In addition, the lack of proper mainte-

nance, due to a lack of equipment to pump out septic tanks,

is likely to have degraded the performance of these systems

even further.

Forty percent of the population in the Republic of

Palau is served by a secondary

sewage treatment

plant in

the state of Koror, which is generally thought to provide

adequate treatment. However, the Koror State government

has expressed concern over the possible contamination of

Malakal Harbor, into which the plant discharges. Also, some

low-lying areas served by the system experience periodic

back-flows of sewage which run into mangrove areas, due

to mechanical failures with pumps and electrical power out-

ages. In other low-lying areas not covered by the sewer

system, septic tanks and latrines are used, which also over-

flow, affecting marine water quality.

Rural areas primarily rely on latrines, causing localized

marine contamination in some areas. Though there have

been an increasing number of septic systems installed as part

of a rural sanitation program funded by the United States,

there is anecdotal evidence that they may not be very effec-

tive. Many of the

septic tank

leach fields may not be of

adequate size. In addition, a number of the systems are not

used at all, as some families prefer instead to use latrines

since the actual toilets and enclosures are not provided with

the septic tanks as part of the program.

Wastewater problems also result from agriculture. Ac-

cording to the EPA, pig waste is considered to be a more

significant problem than human sewage in many areas.

Because sanitation has become a social responsibility,

national, state and local governments have adopted regula-

tions that, when followed, should provide adequate sanita-

tion for the governed society. However, the very technologies

1249

and practices that were instituted to provide better health

and sanitation now have been found to be contaminating

ground and surface waters. For example, placing

chlorine

in drinking water and waste water to provide disinfection,

has now been found to produce carcinogenic compounds

called

trihalomethanes

and

dioxin

. Collecting sanitary

waste and transporting them along with industrial waste to

inadequate treatment plants costing billions of dollars has

failed to provide adequate protection for public health and

environmental security.

Increasingly, the solution seems to be found in meth-

ods and practices that borrow from the stable ecosystems

model of

waste management

. That is, there are no wastes,

only resources that need to be connected to the appropriate

organism that requires the residuals from one organism as

the nutritional requirement of another. New waterless

com-

posting

toilets that destroy human fecal organisms while

they produce

fertilizer

, are now the technology of choice

in the developing world and have also found a growing

niche

in the developed world. Wash water, rather than being

disposed of into ground and surface waters, is now being

utilized for

irrigation

. The combination of these two ecolog-

ically engineered technologies provides economical sanita-

tion, eliminates pollution, and creates valuable fertilizers and

plants, while reducing the use of potable water for irrigation

and toilets.

Simple hand washing is now re-emerging as the most

important measure in preventing disease transmission. Han-

dwashing breaks the primary connection between surfaces

contaminated with fecal organisms and the introduction of

these pathogens into the human body. The use of basic soap

and water, not exotic disinfectants, when practiced before

eating and after defecating may save more lives than all of

the modern methodologies and technologies combined.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Salvato, J. Environmental Engineering and Sanitation. 4th ed. 1992.

“Sanitation Problems in Micronesia.” A report. Concord, MA: Sustainable

Strategies, 1997.

P

ERIODICALS

Fair, G., J. Geyer, and A. Okun. Water and Wastewater Engineering 1 (1992).

Santa Barbara oil spill

On January 28, 1969, a Union Oil Company

oil drilling

platform 6 mi (10 km) off the coast of Santa Barbara, Califor-

nia, suffered a blowout, leading to a tremendous ecological

disaster. Before it could be stopped, 3 million gal (11.4

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Santa Barbara oil spill

million l) of crude oil gushed into the Pacific Ocean, killing

thousands of birds, fish,

sea lions

, and other marine life. For

weeks after the spill, the nightly television news programs

showed footage of the effects of the giant black slick, includ-

ing oil–soaked birds on the shore dead or dying.

Many people viewed the disaster as an event that gave

the modern environmental movement—which began with

the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in

1962—a new impetus in the United States. “The blowout

was the spark that brought the environmental issue to the

nation’s attention,” Arent Schuyler, an environmental studies

lecturer at the University of California at Santa Barbara

(UCSB), said in a 1989 interview with the Los Angeles Times.

“People could see very vividly that their communities could

bear the brunt of industrial accidents. They began forming

environmental groups to protect their communities and

started fighting for legislation to protect the environment,”

Schuyler explained.

The background

The spill began when oil platform workers were pulling

a drilling tube out of one of the

wells

to replace a drill bit.

The pressure differential created by removing the tube was

not adequately compensated for by pumping mud back down

into the 3,500-ft-deep well (about 1,067 m). This action

caused a drastic buildup of pressure, resulting in a blowout;

natural gas

, oil, and mud shot up the well and into the

ocean. The pressure also caused breaks in the ocean floor

surrounding the well, from which more gas and oil escaped.

Cleanup and environmental impact

It took workers 11 days to cap the well with cement.

Several weeks later, a leak in the well occurred, and for

months, the well continued to spew more oil. On the surface

of the ocean, an 800-mi

2

-long (about 1,278 km

2

) oil slick

formed. Incoming tides carried the thick tar-like oil onto

35 mi (56 km) of scenic California beaches—from Rincon

Point to Goleta. The spill also reached the off-shore islands

of Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel.

The Santa Barbara area is known to have some “natu-

ral”

petroleum

seepages, thus allowing for some degree of

adaptability in the local marine plants and animals. However,

the impact of the oil spill on sea life was disastrous. Dozens

of sea lions and

dolphins

were believed killed, and many

were washed ashore. The oil clogged the blowholes of the

dolphins, causing massive bleeding in the lungs, and suffoca-

tion. It has been estimated that approximately 9,000 birds

died as the oil stripped their feathers of the natural water-

proofing that kept them afloat. Multitudes of fish are be-

lieved to have been killed, and many others fled the area,

causing economic harm to the region’s fishermen. A great

number of

whales

migrating from the Gulf of Alaska to

Baja, Mexico, were forced to take a sweeping detour around

the polluted water.

1250

Although hundred of volunteers, many of them UCSB

students, worked on-shore catching and cleaning birds and

mammals, an army of workers used skimmers to scoop up

oil from the ocean surface. Airplanes were used to drop

detergents

on the oil slick to try to break it up. The cleanup

effort took months to complete and cost millions of dollars.

It also had a detrimental effect on tourism in the Santa

Barbara area for many months. The excessively toxic disper-

sants and detergents used in these sensitive habitats also

caused great ecological damage to the area. In later years,

chemicals

used to control petroleum spills were far less toxic.

Legal impact

Environmentalists claimed the spill could have been

prevented and blamed both Union Oil and the U.S.

Geolog-

ical Survey

(USGS). By approving the drilling permit,

USGS officials were waiving current federal safety regula-

tions for the oil company’s benefit. Federal and state investi-

gations also determined that if additional steel-pipe sheeting

had been placed inside the drilling hole, the blowout would

have been prevented. This type of sheeting was required

under the regulations waived by the USGS.

In the years following the oil spill, the state and federal

governments enacted many environmental protection laws,

including the California Environmental Quality Act and the

National Environmental Policy Act

of 1969. The state also

banned offshore oil drilling for 16 years, established the

federal

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and the

California Coastal Commission, and created the nation’first

environmental studies program at UCSB.

[Ken R. Wells]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Jurcik, Liz. Black Tide: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill and Its Consequences.

New York: Delacorte Press, 1972.

P

ERIODICALS

Corwin, Miles. “The Oil Spill Heard ’Round the Country!” Los Angeles

Times (January 28, 1989): A1.

Cowan, Edward. “Mankind’s Fouled Nest.” The Nation (March 10,

1969): 304.

“Grotesque Beauty of a Sea Shimmering With Oil.” Life (February 21,

1969): 58–62.

“Runaway Oil Well: Will It Mean New Rules in Offshore Drilling?” U.S.

News & World Report (February 17, 1969): 14.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue,

NW, Washington, DC USA 20460 (202) 260-2090, Email: public-

access@epa.gov, <http://www.epa.gov>

Santa Barbara Wildlife Care Network, P.O. Box 6594, Santa Barbara, CA

USA 93160 (805) 966-9005, Email: sbwcn@juno.com, <http://

www.silcom.com/~sbwcn/spill.htm>

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Savanna

Saprophyte

A saprophyte is an organism that survives by consuming

nutrients from dead and decaying plant and animal material,

that is, organic matter. Saprophytes include

fungi

, molds,

most bacteria, actinomycetes, and a few plants and animals.

Saprophytes contain no chlorophyll and are, therefore, un-

able to produce food through

photosynthesis

, the conver-

sion of chemical compounds into energy when light is pres-

ent. Organisms that do not produce their own food,

heterotrophs, obtain nutrients from surrounding sources,

living or dead. For saprophytes, the source is non-living

organic matter. Saprophytes are known as

decomposers

.

They absorb nutrients from forest floor material, reducing

complex compounds in organic material into components

useful to themselves, plants, and other

microorganisms

.

For example, lignin, one of three major materials found in

plant cell walls, is not digestible by plant-eating animals

or useable by plants unless broken down into its various

components, mainly complex sugars. Certain saprophytic

fungi are able to reduce lignin into useful compounds. Sapro-

phytes thrive in moist, temperate to tropical environments.

Most require oxygen to live. North American plant sapro-

phytes include truffles, Indian Pipe (Monotropa uniflora),

pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea), and snow orchid (Cepha-

lanthera austinae), all of which feed on forest floor litter in

the northeast forests.

[Monica Anderson]

SARA

see

Superfund Amendments and

Reauthorization Act (1986)

Savanna

A savanna is a dry grassland with scattered trees. Most

ecologists agree that a characteristic savanna has an open or

sparse canopy with 10–25% tree cover, a dominant ground

cover of annual and perennial grasses, and less than 20 in

(50 cm) of rainfall per year. Greatly varied environments,

from open deciduous forests and parklands, to dry, thorny

scrub, to nearly pure

grasslands

, can be considered savan-

nas. At their margins these communities merge, more or

less gradually, with drier prairies or with denser, taller forests.

Savannas occur at both tropical and temperate latitudes and

on all continents except

Antarctica

. Most often savannas

occupy relatively level, or sometimes rolling, terrain. Charac-

teristic savanna soils are dry, well-developed ultisols, oxisols,

and alfisols, usually basic and sometimes lateritic. These soils

develop under savannas’ strongly seasonal rainfall regimes,

1251

with extended dry periods that can last up to 10 months.

Under natural conditions an abundance of insect, bird, rep-

tile, and mammal

species

populate the land.

Savanna shrubs and trees have leathery, sometimes

thorny, and often small leaves that resist

drought

, heat,

and intense sunshine normally found in this

environment

.

Savanna grasses are likewise thin and tough, frequently

growing in clumps, with seasonal stalks rising from longer-

lived underground roots. Many of these plants have oily or

resinous leaves that burn intensely and quickly in a fire.

Extensive root systems allow most savanna plants to exploit

moisture and nutrients in a large volume of

soil

. Most sa-

vanna trees stand less than 32 ft (10 m) tall; some have a

wide spreading canopy while others have a narrower, more

vertical shape. Characteristic trees of African and South

American savannas include acacias and miombo

(Brachystegia spp.). Australian savannas share the African

baobab, but are dominated by eucalyptus species. Oaks char-

acterize many European savannas, while in North America

oaks, pines, and aspens are common savanna trees.

Because of their extensive and often nutritious grass

cover, savannas support extensive populations of large herbi-

vores. Giraffes,

zebras

, impalas, kudus, and other charis-

matic residents of African savannas are especially well-

known. Savanna herbivores in other regions include North

American

bison

and elk and Australian kangaroos and wal-

labies. Carnivores—lions, cheetahs, and jackals in Africa,

tigers

in Asia,

wolves

and pumas in the Americas—histori-

cally preyed upon these huge herds of grazers. Large running

birds, such as the African ostrich and the Australian emu,

inhabit savanna environments, as do a plethora of smaller

animal species. In the past century or two many of the

world’s native savanna species, especially the large carnivores,

have disappeared with the expansion of human settlement.

Today ranchers and their livestock take the place of many

native grazers and carnivores.

Savannas owe their existence to a great variety of con-

vergent environmental conditions, including temperature

and precipitation regimes, soil conditions, fire frequency,

and

fauna

. Grazing and browsing activity can influence the

balance of trees to grasses. Fires, common and useful for

some savannas but rare and harmful in others, are an influen-

tial factor in these dry environments. Precipitation must be

sufficient to allow some tree growth, but where rainfall is

high some other factors, such as grazing, fire, or soil

drain-

age

needs to limit tree growth. Human activity also influ-

ences the occurrence of these lightly-treed grasslands. In

some regions recent expansion of ranches, villages, or agricul-

ture have visibly extended savanna conditions. Elsewhere

centuries or millennia of human occupation make natural

and

anthropogenic

conditions difficult to distinguish. Be-

cause savannas are well suited to human needs, people have

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Savannah River Site

occupied some savannas for tens of thousands of years. In

such cases people appear to be an environmental factor, along

with

climate

, soils, and grazing animals, that help savannas

persist. See also Deforestation

[Mary Ann Cunningham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Cole, M. M. The Savannas: Biogeography and Geobotany. London: Academic

Press, 1986.

Danserreau, P. Biogeography: An Ecological Perspective. New York: Ronald

Press Company, 1957.

de Laubenfels, D. J. Mapping the World’s Vegetation. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse

University Press, 1975.

White, R. O. Grasslands of the Monsoon. New York: Praeger, 1968.

Savannah River Site

From the 1950s to the 1990s, the manufacture of

nuclear

weapons

was a high priority item in the United States. The

nation depended heavily on an adequate supply of atomic

and

hydrogen

bombs as its ultimate defense against enemy

attack. As a result, the government had established 17 major

plants in 12 states to produce the materials needed for nuclear

weapons.

Five of these plants were built along the Savannah

River near Aiken, South Carolina. The Savannah River Site

(SRS) is about 20 mi (32 km) southeast of Augusta, Georgia,

and 150 mi (242 km) upstream from the Atlantic Ocean.

The five reactors sit on a 310 mi

2

(803 km

2

) site that also

holds 34 million gal (129 million l) of high-level radioactive

wastes.

The SRS reactors were originally used to produce

plu-

tonium

fuel used in nuclear weapons. In recent years, they

have been converted to the production of tritium gas, an

important component of fusion (hydrogen) bombs.

For more than a decade, environmentalists have been

concerned about the safety of the SRS reactors. The reactors

were aging; one of the original SRS reactors, for instance,

had been closed in the late 1970s because of cracks in the

reactor vessel.

The severity of safety issues became more obvious,

however, in the late 1980s. In September 1987, the

U.S.

Department of Energy

(DOE) released a memorandum

summarizing 30 “incidents” that had occurred at SRS be-

tween 1975 and 1985. Among these were a number of unex-

plained power surges that nearly went out of control. In

addition, the meltdown of a radioactive fuel element in

November 1970 took 900 people three months to clean up.

E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, operator of

the SRS facility, claimed that all “incidents” had been prop-

1252

erly reported and that the reactors presented no serious risk

to the area. Worried about maintaining a dependable supply

of tritium, DOE officials accepted du Pont’s explanation

and allowed the site to continue operating.

In 1988, however, the problems at SRS began to snow-

ball. By that time, two of the original five reactors had been

shut down permanently and two, temporarily. Then, in Au-

gust of 1988 an unexplained power surge caused officials to

temporarily close down the fifth, “K,” reactor. Investigations

by federal officials found that the accident was a result of hu-

man errors. Operators were poorly trained and improperly su-

pervised. In addition, they were working with inefficient,

aging equipment that lacked adequate safety precautions.

Still concerned about its tritium supply, the DOE

spent more than $1 billion to upgrade and repair the K

reactor and to retrain staff at SRS. On December 13, 1991,

Energy Secretary James D. Watkins announced that the

reactor was to be re-started again, operating at 30% capacity.

During final tests prior to re-starting, however, 150

gal (569 l) of cooling water containing radioactive tritium

leaked into the Savannah River. A South Carolina water

utility company and two food processing companies in Sa-

vannah, Georgia, had to discontinue using river water in

their operations.

The ill-fated reactor experienced yet another set-back

only five months later. During another effort at re-starting

the K reactor in May 1992, radioactive tritium once again

escaped into the surrounding

environment

and, once again,

start-up was postponed.

By the fall of 1992, changes in the balance of world

power would cast additional doubt on the future of SRS.

The Soviet Union had collapsed and neither Russia nor its

former satellite states were regarded as an immediate threat

to U.S. security, as former Soviet military might was now

spread among a number of nations with urgent economic

priorities. American president George Bush and Russian

leader Boris Yeltsin had agreed to sharp cut-backs in the

number of nuclear warheads held by both sides. In addition,

experts determined that the existing supply of tritium would

be sufficient for U.S. defense needs until at least 2012.

In 2000, the K reactor was turned into a materials

storage facility. The site will soon be put back into action

after the delivery of 6 tons of plutonium in June of 2002.

The plutonium will be held at the site until it is converted

into nuclear reactor fluid by 2017. If the plutonium has not

been converted, it will be transferred to an other location.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Applebome, P. “Anger Lingers After Leak at Atomic Site.” New York

Times (January 13, 1992): A7.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Save-the-Redwoods League

Schneider, K. “U.S. Dropping Plan to Build Reactor.” New York Times

(September 12, 1992): 5.

Sharp, Deborah. “Six Tons of Plutonium begin Journey to S.C.” USA Today

June 24, 2002 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/

2002/06/25/plutonium-usat.htm>.

Sweet, W. “Severe Accident Scenarios at Issue in DOE Plan to Restart

Reactor.” Physics Today (November 1991): 78–81.

Wald, M. L. “How an Old Government Reactor Managed to Outlive the

Cold War.” New York Times (December 22, 1991): E2.

Save the Whales

Save the Whales is a non-profit, grassroots organization that

was founded and incorporated in 1977. It was conceived by

14-year-old Maris Sidenstecker II when she learned that

whales

were being cruelly slaughtered. She designed a T-

shirt with a logo that read “Save the Whales” and designated

the proceeds to help save whales. Her mother, Maris Sidens-

tecker I, helped co-found the organization and still serves

as its executive director.

Unlike some environmental groups,

Greenpeace

for

example, Save the Whales is involved in very few direct

action protests and activities. Its primary focus is education.

The group’s educational staff is comprised of marine biolo-

gists, environmental educators, and researchers. They speak

to school groups, senior citizen organizations, clubs, and

numerous other organizations. Save the Whales is opposed

to commercial

whaling

and works to save all whale

species

from

extinction

. The group also sends a representative to

the annual International Whaling Commission conference.

WOW!, Whales On Wheels, is an innovative program

developed by Save the Whales. WOW! travels throughout

California educating thousands of children and adults about

marine mammals and their

environment

. WOW! features

live presenters and incorporates audio and video into the

program along with hands-on exhibits and marine mammal

activity projects. In 1992 alone, Maris Sidenstecker II gave

presentations to over 7,000 school children.

Save the Whales has also developed a regional Marine

Mammal Beach Program for school aged children. It consists

of an abbreviated WOW! lecture after which the participants

assist in cleaning up a beach. Save the Whales has adopted

Venice Beach in California and cleans it several times a year.

A five-minute educational video entitled “One Person

Makes A Difference” has been produced by Save the Whales.

It combines footage of the humpback whales, orcas, and

gray whales in the wild which is followed by shots of the

slaughter of pilot whales in the Faroe Islands. The video

ends with brief interviews that advocate whale

conservation

and describe the ways in which one person can make a

difference. Save the Whales is currently involved in raising

funds to produce a 30-minute documentary film entitled

“Barometers of The Ocean.” This video will explore chemi-

1253

cal

pollution

in the oceans and how it is affecting whale

populations.

The organization also supports marine mammal re-

search. It helps finance research on

seals and sea lions

in

Puget Sound (Washington), and makes financial contribu-

tions to SCAMP (Southern California

Migration

Project)

to support studies of gray whale migration. Save the Whales

publishes a quarterly newsletter that is free with membership,

and the organization currently has 2,000 members

worldwide.

[Debra Glidden]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Save The Whales, P.O. Box 2397, Venice, CA USA 90291 Email:

maris@savethewhales.org, <http://www.savethewhales.org>

Save-the-Redwoods League

The Save-the-Redwoods League was founded in 1918 to

protect California’s redwood forests for

future generations

to enjoy. Prominent individuals involved in the formation

of the League included Stephen T. Mather, first Director

of the

National Park Service

; Congressman William Kent,

author of the bill creating the

National Park

Service; New-

ton Drury, Director of the National Park Service from 1940–

1951; and John Merriam, paleontologist and later president

of the Carnegie Institute. The impetus for forming the orga-

nization was a trip taken in 1917 by several of these men

and others during which they witnessed widespread destruc-

tion of the forests by loggers. They were appalled to learn

that not one tree was protected by either the state or the

federal government. Upon their return, they wrote an article

for National Geographic detailing the devastation. Shortly

thereafter they formed the Save-the-Redwoods League. One

of the League’s first actions was to recommend to Congress

that a

Redwoods

National Park be established.

The specific stated objectives of the organization are:

O

“to rescue from destruction representative areas of our pri-

meval forests,

O

to cooperate with the California State Park Commission,

the National Park Service, and other agencies, in establish-

ing redwood parks, and other parks and reservations,

O

to purchase redwood groves by private subscription,

O

to foster and encourage a better and more general under-

standing of the value of the primeval redwood or sequoia

and other forests of America as natural objects of extraordi-

nary interest to present and future generations,

O

to support reforestation and

conservation

of our forest

areas.”

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Scarcity

This non-profit organization uses donations to pur-

chase redwood lands from willing sellers at fair market value.

All contributions, except those specified for research or refor-

estation, are used for land acquisition.

The League’s members and donors have given more

than $70 million in private contributions since the formation

of the organization. These monies have been used to purchase

and protect more than 130,000 acres (52,609 ha) of redwood

park land. The establishment of the Redwoods National Park

in 1968, and the park’s subsequent expansion in 1978, repre-

sented milestones for the Save-the-Redwoods League which

had fought for such a national park for 60 years.

Mere acquisition of the redwood groves does not en-

sure the long-term survival of the redwoods

ecosystem

.

Based on almost 70 years of study by park planners and

ecologists, a major goal of the Save-the-Redwoods League is

to complete each of the existing redwoods parks as ecological

units along logical

watershed

boundary lines. The acquisi-

tion of these watershed lands are necessary to act as a buffer

around the groves to protect them from effects of adjacent

logging

and development.

[Ted T. Cable]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Save-the-Redwoods League, 114 Sansome Street, Room 1200, San

Francisco, CA USA 94104-3823 (415) 362-2352, Fax: (415) 362-7017,

Email: info@savetheredwoods.org, <http://www.savetheredwoods.org>

Scarcity

As most commonly used, the term scarcity refers to a limited

supply of some material. With the rise of environmental

consciousness in the 1960s, scarcity of

natural resources

became an important issue. Critics saw that the United States

and other developed nations were using natural resources

at a frightening pace. How long, they asked, could non-

renewable resources such as

coal

, oil,

natural gas

, and

metals last at the rate they were being consumed?

A number of studies produced some frightening pre-

dictions. The world’s oil reserves could be totally depleted

in less than a century, according to some experts, and scarce

metals such as silver,

mercury

, zinc, and

cadmium

might

be used up even faster at then-current rates of use.

One of the most famous studies of this issue was that

of the

Club of Rome

, conducted in the early 1970s. The

Club of Rome was an international group of men and women

from 25 nations concerned about the ultimate environmental

impact of continued

population growth

and unlimited de-

velopment. The Club commissioned a complex computer

study of this issue to be conducted by a group of scholars

1254

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The result of

that study was the now famous book The Limits to Growth.

Limits presented a depressing view of the Earth’s future

if population and technological development were to con-

tinue at then-current rates. With regard to non-renewable

resources such as metals and

fossil fuels

, the study concluded

that the great majority of those resources would become

“extremely costly 100 years from now.” Unchecked popula-

tion growth and development would, therefore, lead to wide-

spread scarcity of many critical resources.

The Limits argument appears to make sense. There is

only a specific limited supply of coal, oil, chromium, and

other natural resources on Earth. As population grows and

societies become more advanced technologically, those re-

sources are used up more rapidly. A time must come, there-

fore, when the supply of those resources becomes more and

more limited, that is, they become more and more scarce.

Yet, as with many environmental issues, the obvious re-

ality is not necessarily true. The reason is that there is a second

way to define scarcity, an economic definition. To an econo-

mist, a resource is scarce if people pay more money for it. Re-

sources that are bought and sold cheaply are not scarce.

One measure of the Limits argument, then is to follow

the price of various resources over time, to see if they are

becoming more scarce in an economic sense. When that

study is conducted, an interesting result is obtained. Suppos-

edly “scarce” resources such as coal, oil, and various metals

have actually become less costly since 1970 and must be

considered, therefore, to be less scarce than they were two

decades ago.

How this can happen has been explained by economist

Julian Simon, a prominent critic of the Limits message. As

the supply of a resource diminishes, Simon says, humans

become more imaginative and more creative in finding and

using the resource. For example, gold mines that were once

regarded as exhausted have been re-opened because im-

proved technology makes it possible to recover less concen-

trated reserves of the metal. Industries also become more

efficient in the way they use resources, wasting less and

making what they have go further.

In one sense, this debate is a long-term versus short-

term argument. One can hardly argue that the Earth’s supply

of oil, for example, will last forever. However, given Simon’s

argument, that supply may last much longer than the authors

of Limits could have imagined twenty years ago.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Meadows, D. H., et al. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe

Books, 1972.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher

Ophuls, W., and A. S. Boyan Jr. Ecology and the Politics of Scarcity Revisited.

San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1992.

Simon, J. L. and H. Kahn, eds. The Resourceful Earth. Oxford: Basil Black-

well, 1984.

———. The Ultimate Resource. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press, 1981.

Scavenger

Any substance or organism that cleans a setting by removing

dirt, decaying matter, or some other unwanted material.

Vultures are typical biological scavengers because they feed

on the carcasses of dead animals. Certain

chemicals

can act

as scavengers in chemical reactions. Lithium and magnesium

are used in the metal industry as scavengers since these

metals react with and remove small amounts of oxygen and

nitrogen

from molten metals. Even rain and snow can be

regarded as scavengers because they wash pollutants out of

the

atmosphere

.

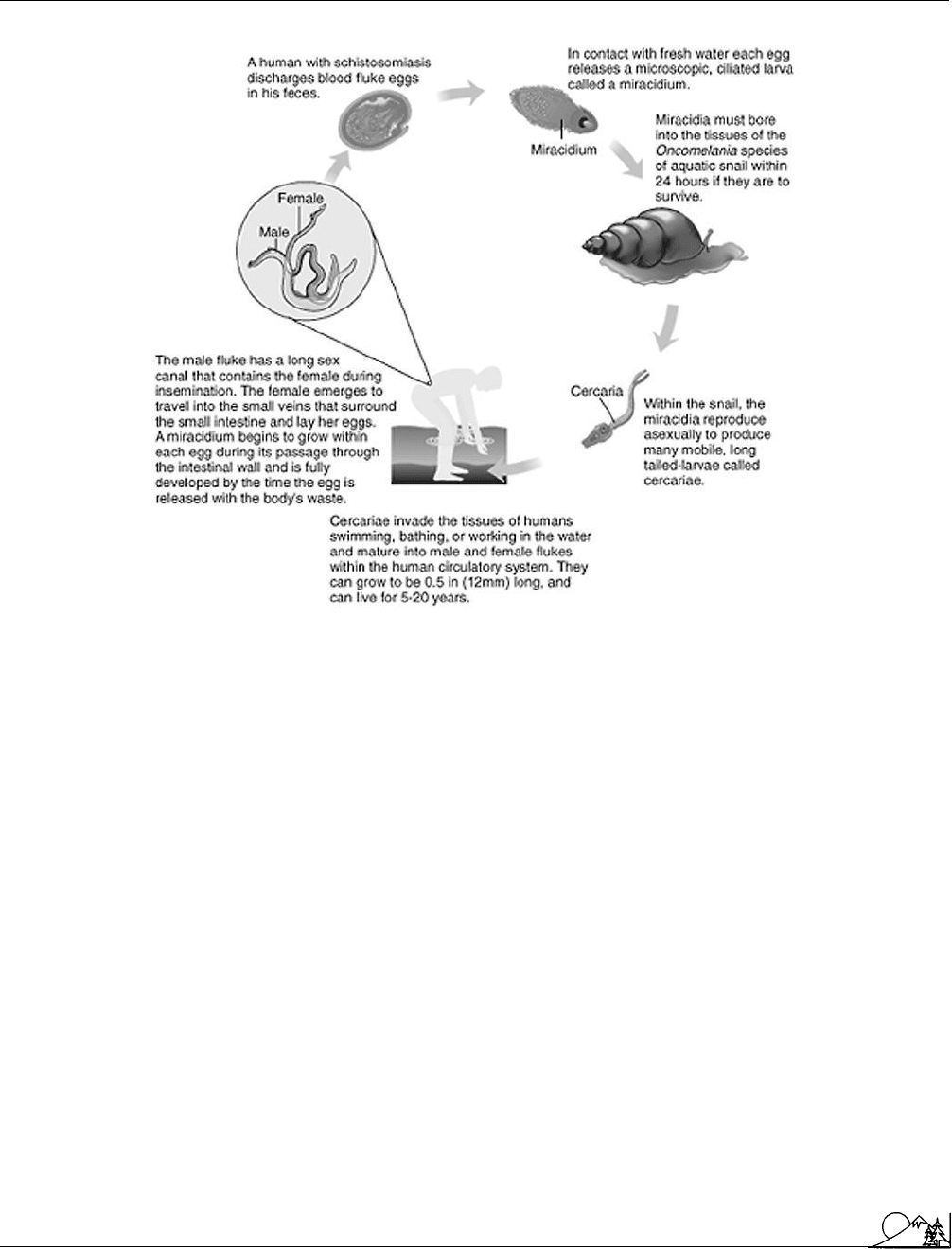

Schistosomiasis

Human blood fluke disease, also called schistosomiasis or

bilharziasis, is a major parasitic disease affecting over 200

million people worldwide, mostly those in the tropics. Al-

though sometimes fatal, schistosomiasis more commonly

results in chronic ill-health and low energy levels. The disease

is caused by small parasitic flatworms of the genus Schisto-

soma. Of the three

species

, two (S. haematobium and S.

mansoni) are found in Africa and the Middle East, the third

(S. japonicum) in the Orient. Schistosoma haematobium lives

in the blood vessels of the urinary bladder and is responsible

for over 100 million human cases of the disease a year.

Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum reside in the

intestine; the former species infect 75 million people a year

and the latter 25 million.

Schistosomiasis is spread when infected people urinate

or defecate into open waterways and introduce parasite eggs

that hatch in the water. Each egg liberates a microscopic

free-living larva called the miracidium which bores into the

tissues of a water snail of the genus Biomphalaria, Bulinus,

or Onchomelania, the intermediate host. Inside the snail the

parasite multiplies in sporocyst sacs to produce masses of

larger, mobile, long-tailed larvae known as cercariae. The

cercariae emerge from the snail into the water, actively seek

out a human host, and bore deep into the skin. Larvae that

reach the blood vessels are carried to the liver where they

develop into adult egg-producing worms that settle in the

vessels of the urinary bladder or intestine. Adult Schistosoma

live entwined in mating couples inside the small veins of

their host. Fertilized females release small eggs (0.2 mm

1255

long), at the rate of 3,500 per day, which are carried out of

the body with the urine or the feces.

The symptoms of schistosomiasis correlate with the

progress of the disease. Immediately after infection migrat-

ing cercariae cause itching skin. Subsequent establishment

of larvae in the liver damages this organ. Later, egg release

causes blood in the stool (dysentery), damage to the intestinal

wall, or blood in the urine (hematuria), and damage to the

urinary bladder.

Schistosomiasis is increasing in developing countries

due in part to rapidly increasing human populations. In rural

areas, attempts to increase food production that include more

irrigation

and more

dams

also increase the

habitat

for

water snails. In urban areas the combination of crowding and

lack of

sanitation

ensures that increasingly large numbers of

people become exposed to the parasite.

Most control strategies for schistosomiasis target the

snail hosts. One strategy kills snails directly by adding snail

poisons (molluscicides) to the water. Another strategy either

kills or removes vegetation upon which snails feed. Biological

methods of snail control include the introduction of fish

that feed on snails, of snails that kill schistosome snail hosts,

of insect larvae that prey on snails, and of flukes that kill

schistosomes inside the snail. Some countries, such as Egypt,

have attempted to eliminate the parasite in humans through

mass treatment with curative drugs including ambilar, niri-

dazole, nicolifan, and praziquantel. Total eradication pro-

grams for schistosomiasis focus both on avoiding contact

with the parasite through education, better sanitation, and

on breaking its life cycle through snail control and human

treatment.

[Neil Cumberlidge Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Basch, P. F. Schistosomes: Development, Reproduction, and Host Relations.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Bullock, W. L. People, Parasites, and Pestilence: An Introduction to the Natural

History of Infectious Disease. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company,

1982.

Malek, E. A. Snail-Transmitted Parasitic Diseases. Boca Raton: CRC

Press, 1980.

Markell, E. K., M. Voge, and D. T. John. Medical Parasitology. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Saunders, 1992.

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher (1911 –

1977)

German/English economist

E. F. Schumacher combined his background in economics

with an extensive background in theology to create a unique

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher

The life cycle of the blood fluke. This parasite causes the disease schistosomiasis in humans. (Illustration by Hans &

Cassidy.)

strategy for reforming the world’s socioeconomic systems,

and by the early 1970s he had risen nearly to folk hero status.

Schumacher was born in Bonn, Germany. He attended

a number of educational institutions, including the universi-

ties of Bonn and Berlin, as well as Columbia University

in the United States. He eventually received a diploma in

economics from Oxford University, and emigrated to En-

gland in 1937. During World War II, Schumacher was

forced to work as a farm laborer in an internment camp. By

1946, however, he had become a naturalized British citizen,

and in that same year he accepted a position with the British

section of the Control Commission of West Germany. In

1953 he was appointed to Great Britain’s National Coal

Board as an economic advisor, and in 1963 he became direc-

tor of

statistics

there. He stayed with the National Coal

Board until 1970.

Schumacher recognized the contemporary indifference

to the course of world development, as well as its implica-

tions. He began to seek alternative plans for

sustainable

development

, and his interest in this issue led him to found

the Intermediate Technology Development Group in 1966.

1256

Today, this organization continues to provide information

and other assistance to

less developed countries

. Schu-

macher believed that in order to build a global community

that would last, development could not exploit the

environ-

ment

and must take into account the sensitive links between

the environment and human health. He promoted research

in these areas during the 1970s as president of the Soil

Association, an organization that advocates

organic farm-

ing

worldwide.

Schumacher also combined his studies of Buddhist

and Roman Catholic theology into a philosophy of life. In

his highly regarded book, Small is Beautiful: Economics as if

People Mattered (1973), he stresses the importance of self-

reliance and promotes the virtues of working with

nature

rather than against it. He argues that continuous economic

growth is more destructive than productive, maintaining that

growth should be directly proportionate to human need.

People in society, he continues, should apply the ideals of

conservation

(durable-goods production,

solar energy

,

recycling

) and appropriate technology in their lives when-

ever possible.