Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment

In his A Guide For the Perplexed (1977), published in

1977, Schumacher is even more philosophical. He attempts

to provide personal rather than global guidance, encouraging

self-awareness and urging individuals to embrace what he

termed a “new age” ethic based on Judeo-Christian princi-

ples. He also wrote various pamphlets, including: Clean Air

and Future Energy, Think About Land, and Education for the

Future.

Schumacher died in 1977 while traveling in Switzer-

land from Lausanne to Zurich.

[Kimberley A. Peterson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Schumacher, E. F. A Guide for the Perplexed. New York: Harper &

Row, 1977.

———. Small is Beautiful: Economics As If People Mattered. London: Blond

and Briggs, 1973.

P

ERIODICALS

Fraker, S., and G. C. Lubenow. “Mr. Small.” Newsweek (March 28,

1977): 18.

“Why It Is Important to Think Small.” International Management (August

1977): 18–20.

Albert Schweitzer (1875 – 1965)

German theologian, musicologist, philosopher, and phy-

sician

Albert Schweitzer was an individual of remarkable depth

and diversity. He was born in the Upper Alsace region of

what is now Germany. His parents, Louis (an Evangelical

Lutheran pastor and musician) and Adele cultivated his in-

quisitive mind and passion for music. He developed a strong

theological background and, under his father’s tutelage, stud-

ied piano, eventually acting as substitute musician at the

church.

As a young adult, Schweitzer pursued extensive studies

in philosophy and theology at the University of Strasbourg,

where he received doctorate degrees in both fields (1899

and 1900 respectively). He continued to further his interests

in music. While on a fellowship in Paris (researching Kant),

he also studied organ at the Sorbonne. He began a career

as an organist in 1893 and was eventually renowned as expert

in the area of organ construction and as one of the finest

interpreters and scholars of Johann Sebastian Bach. His

multitudinous published works include the respected J. S.

Bach: the Musician Poet (1908).

In 1905, after years of pursuing various careers—in-

cluding minister, musician, and teacher—he determined to

dedicate his work to the benefit of others. In 1913 he and his

wife, Helene, traveled to Lambarene in French Equatorial

1257

Africa (now Gabon), where they built a hospital on the

Ogowe River. At the outbreak of World War I, they were

allowed to continue working at the hospital for a time but

were then sent to France as prisoners of war (both were

German citizens). They were held in an internment camp

until 1918. After their release, the Schweitzers remained in

France and Albert returned to the pulpit. He also gave organ

concerts and lectures. During this time in France he wrote

“Philosophy of Civilization” (1923), an essay in which he

described his philosophy of “reverence for life.” Schweitzer

felt that it was the responsibility of all people to “sacrifice

a portion of their own lives for others.” The Schweitzers

returned to Africa in 1924, only to find their hospital over-

grown with jungle vegetation. With the assistance of volun-

teers, the facility was rebuilt, using typical African villages

as models.

Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, Schweitzer

used $33,000 of the Prize money to establish a leper colony

near the hospital in Africa. It was not until late 1954 that

he gave his Nobel lecture in Oslo. He took advantage of

the opportunity to object to war as “a crime of inhumanity.”

Three more years passed before Schweitzer sent out an im-

passioned plea to the world in his “Declaration of Con-

science,” which he read over Oslo radio. He called for citizens

to demand a ban of

nuclear weapons

testing by their

governments. His words ignited a series of arms control talks

among the superpowers that began in 1958 and, five years

later, resulted in a limited but formal test-ban treaty.

Schweitzer received numerous awards and degrees.

Among his long list of published works are The Quest of the

Historical Jesus (1906), The Mysticism of Paul the Apostle

(1931), Out of My Life and Thought (1933, autobiography),

and The Light Within Us (1959). He died at the age of 90

at Lambarene.

[Kimberley A. Peterson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bentley, J. Albert Schweitzer: The Enigma. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

Miller, D. C. Relevance of Albert Schweitzer at the Dawn of the Twenty-

First Century. Lanham: University Press of America, 1992.

Schweitzer, A. Out of My Life and Thought. New York: Henry Holt, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Negri, M. “The Humanism of Albert Schweitzer.” Humanist 53 (March–

April 1993): 26–31.

Scientific Committee on Problems of

the Environment

The Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Scientists’ Institute for Public Information

(SCOPE) is a worldwide group of 22 international science

unions and 40 national committees that work together on

issues pertaining to the environment. SCOPE was founded

in 1969 and today is headquartered in Paris, France. SCOPE

stands as a permanent committee of the International Coun-

cil for Science.

SCOPE describes its organization as “an interdisci-

plinary body of natural and social science expertise focused

on global environmental issues, operating at the interface

between scientific and decision-making instances” and “a

worldwide network of scientists and scientific institutions

developing syntheses and reviews of scientific knowledge on

current or potential environmental issues.” The committee

aims to determine not only how human activities impact the

environment, but also how environmental changes impact

people’s health and welfare.

With its broad international nature, SCOPE acts as

an independent source of information for governments and

nongovernmental entities around the world by offering re-

search and consulting expertise on environmental topics. In

past years, the committee has gathered scientists to produce

reports including possible effects of nuclear war,

biosphere

programs to keep the earth inhabitable, and

radioactive

waste

.

SCOPE’s scientific program focuses on three main

areas: managing societal and

natural resources

,

ecosystem

processes and

biodiversity

, and health and the environment.

Managing societal and natural resources involves those proj-

ects that are founded on scientific research but that can be

applied in a practical manner to help sustain the biosphere.

In other words, the committee wants to ensure that Earth

can continue to produce the fuel, food, and other natural

resources needed to support the population. As of early 2002,

nearly a dozen projects involving biosphere development,

urban

waste management

, agriculture,

conservation

, and

others fell under the spectrum of this SCOPE task.

Ecosystem processes and biodiversity projects focus

on how ecosystems interact with human activities. These

projects look at how activities such as mining and movement

of substances such as

nitrogen

in rivers will affect the earth’s

land and water. Projects also look at changes in Earth’s

climate

and the impact that those changes may have on

future

ecology

.

The committee’s health and environment projects de-

velop methods to assess chemical risks of various activities

to humans, plants, animals, and habitats. For example, the

committee is working on a project involving the study of

effects of

mercury

, particularly in aquatic environments.

Another major project studies

radioactivity

at nuclear sites.

Called RADSITE, the project aims to review radioactive

wastes generated in development of

nuclear weapons

.

1258

In addition to its own work and affiliation with the

International Council for Science, SCOPE works in partner-

ship with several international bodies including the United

Nations Education, Social and Culture Organization (UN-

ESCO), and the International Human Dimensions Program

on Global Environmental Change (IHDP). SCOPE is a

unique organization in its international scientific approach

to, and cooperation on, environmental issues.

[Teresa G. Norris]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

O’Riordan, T. “A New Science for a New Age; New Scientist 133 (January

25, 1992): 14.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE), %1,

blvd. De Montmorency F-75016, Paris, France 33-1-45250498, Fax: 33-

1-42881466, Email: secretariat@icsu-scope-org, <http://www.icsu-

scope.org>

Scientists’ Institute for Public

Information

Working to bridge a gap they perceive between scientists

and the media, the Scientists’ Institute for Public Informa-

tion (SIPI) was established in 1963 to disseminate expert

information on science and technology to journalists through

a variety of means.

SIPI’s best-known program is the Media Resource

Service (MRS), which was founded in 1980. The MRS

serves as a referral service for journalists seeking information

from scientists, engineers, physicians, and policymakers. The

MRS maintains a database listing more than 30,000 experts

who are available for and willing to comment on a variety

of topics. The service is free to any media outlet. The honor-

ary chair of the MRS advisory committee is the highly

regarded newscaster Walter Cronkite. The MRS is funded

by such noteworthy news organizations as CBS Inc., the

Scripps Howard Foundation, Time Warner, The Washing-

ton Post Company, the Associated Press, the National

Broadcasting Company, and The New York Times Com-

pany Foundation.

In addition to the MRS, SIPI operates the Videotape

Referral Service (VRS), another free resource service which

aids broadcast journalists in finding videotapes to accompany

science- and technology-related stories. The VRS also pro-

vides a list of videotapes for an annual SIPI conference called

“TV News: The Cutting Edge,” a meeting of scientists,

television news directors, and science reporters. The VRS

also publishes a monthly newsletter featuring topical listings

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Scrubbers

of story ideas and a current catalogue of available videotapes

on science-related issues.

An outgrowth of the MRS, SIPI also operates the

International Hot Line in connection with its Global

Change program. The hotline provides assistance to journal-

ists worldwide by referring them to scientists and environ-

mental experts. The Global Change program holds briefings

to update the media on current international scientific and

environmental issues as well.

SIPI also organizes roundtable discussions, seminars,

and symposia for scientists and national journalists. These

programs have focused on such issues as nuclear waste dis-

posal, military technology and budget priorities, and human

gene therapy. SIPI has also developed smaller-scale versions

of these programs for state and regional press associations

and journalism schools.

In addition, SIPI sponsors the Defense Writers

Group. This group is made up of members of the Pentagon

press corps who gather to discuss views with defense experts.

In addition, SIPI publishes a newsletter addressing current

issues in science policy and featuring reviews of media cover-

age of science and technology.

[Kristin Palm]

SCOPE

see

Scientists’ Committee on Problems of

the Environment

Scotch broom

Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) is a member of the pea

family that is native to southern Europe and northern Africa.

It can grow up to 10 ft (3 m) in height. Scotch broom’s

yellow flowers are shaped like peas, and its leaves each have

three leaflets.

During the 1800s, Scotch broom was introduced into

the United States as an ornamental plant. In addition, people

used the plant for sweeping and make beer and tea with the

seeds. During the mid-1800s, Scotch broom was planted in

the western United States to stabilize roads and prevent

soil

erosion

. By the end of the twentieth century, the nonnative

plant was classified as an invasive weed in the Pacific North-

west and in parts of the northeastern United States and

southeastern Canada.

Scotch broom is a hearty plant that grows quickly. Its

seeds can last 80 years. Thick fields of Scotch broom can

crowd out vegetation that is native to an area. Spread of the

plant can reduce the amount of grazing

habitat

for animals.

Broom can block pathways used by

wildlife

. In addition,

broom can be a fire hazard.

1259

Methods of controlling the spread of Scotch broom

include removing the plant by its roots, spraying

herbicide

,

and controlled burning to destroy seeds.

[Liz Swain]

Scrubbers

Scrubbers are

air pollution control

devices that help cleanse

the emissions coming out of an incinerator’s

smoke

stack.

Hot exhaust gas comes out of the incinerator duct and

scrubbers help to wash the

particulate

matter (dust) re-

sulting from the

combustion

out of the gas. High efficiency

scrubbers literally scrub the smoke by mixing dust particles

and droplets of water (as fine as mist) together at a very

high speed. Scrubbers force the dust to move like a bullet

fired at high velocity into the water droplet. The process is

similar to the way that rain washes the air.

Scrubbers can also be used as absorbers.

Absorption

dissolves material into a liquid, much as sugar is absorbed

into coffee. From an

air pollution

standpoint, absorption

is a useful method of reducing or eliminating the

discharge

of air contaminants into the

atmosphere

. The gaseous air

contaminants most commonly controlled by absorption in-

clude

sulfur dioxide

,

hydrogen

sulfide, hydrogen chloride,

chlorine

, ammonia,

nitrogen oxides

, and light

hydro-

carbons

.

Gas absorption equipment is designed to provide thor-

ough contact between the gas and liquid solvent in order to

permit interphase diffusion and solution of the materials.

This contact between gas and liquid can be accomplished

by dispersing gas in liquid and visa versa. Scrubbers help

wash out polluting

chemicals

from the exhaust gas by facili-

tating the mixture of liquid (solvent) and gas together.

A number of engineering designs serve to disperse

liquid. These include a packed tower, a spray tower or spray

chamber, venturi absorbers, and a bubble tray tower.

The most appropriate design for

incineration

facilities

is the packed tower—a tower filled with one of many avail-

able packing materials. The packing material should provide

a large surface area and, for good fluid flow, should be shaped

to give large void space when packed. It should also be

chemically inert and inexpensive. It must be designed so as

to expose a large surface area and be made of materials, such

as stainless steel, ceramic or certain forms of plastic.

Packing materials come in various manufactured

shapes. They may look like a saddle, a thick tube, a many-

faceted star, a scouring pad, or a cylinder with a number of

holes carved in it. Packing may be dumped into the column

at random or stacked in some kind of order. Randomly

dumped packing has a higher gas pressure drop across the

bed. The stacked packings have an advantage of lower pres-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sea level change

sure and higher possible liquid throughout, but the installa-

tion cost is much higher because they are packed by hand.

Rock and gravel have also been used as packing materi-

als but are usually considered too heavy. They also have

small surface areas, give poor fluid flow and at times are not

chemically inert.

The liquid is introduced at the top of the tower and

trickles down through to the bottom. Since the effectiveness

of a packed tower depends on the availability of a large,

exposed liquid film, poor liquid distribution that prevents a

portion of the packing from being irrigated renders that

portion of the tower ineffective. Poor distribution can result

from improper introduction of the liquid at the top of the

tower or using the wrong rate of liquid flow. The liquid rate

must be sufficient to wet the packing but not flood the

tower. A liquid rate of at least 800 pounds of liquid per

hour per square foot of tower cross-section is typical.

While the liquid introduced at the top of the tower

trickles down through the packing, the gas is introduced at

the bottom and passes upward through the packing. This

process results in the highest possible efficiency. Where the

gas stream and solvent enter at the top of the column, there

is initially a very high rate of absorption that constantly

decreases until the gas and liquid exit in equilibrium.

Scrubbers are used in

coal

burning industries that

generate electricity. They can be used in high sulfur coal

emissions because high sulfur coal emits high levels of sulfur

dioxide. Scrubbers are also utilized in industrial chemical

manufacturing as an important operation in the production

of a chemical compound. For example, one step in the manu-

facture of hydrochloric

acid

involves the absorption of hy-

drochloric acid gas in water. Scrubbers are used as a method

of recovering valuable products from gas streams—as in

petroleum

production where natural

gasoline

is removed

from gas streams by absorption in a special hydrocarbon oil.

See also Air pollution; Flue-gas scrubbing; Tall stacks

[Liane Clorfene Casten]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Schiffner, K. C. Wet Scrubbers. Chelsea, MI: Lewis, 1986.

P

ERIODICALS

“Fume Scrubbers Benefit Environment and Manufacturing.” Design News

48 (August 24, 1992): 28–9.

“Scrubbing Emissions.” Environment 31 (March 1989): 22.

Sea cows

see

Manatees

1260

Sea level change

For at least tens of thousands of years, changes in sea level

seem to be a natural part of the earth’s

environment

.Up

until a few hundred years ago, these changes, both up and

down, occurred due to land movement, ice melting from

glaciers, and an increase or decrease in the amount of water

trapped in the polar ice caps. In most cases, the changes

were very gradual in human terms. But in the past several

decades, many scientists have become alarmed at the rapid

increase in ocean levels.

The reason is because the earth is heating up, which

causes sea water to expand in volume and ice caps to melt.

Over the past 100 years, scientists have measured a mean

sea level rise of about 4 in (10 cm). They blame it on

an average increase of 1.8°F (1°C) in world-wide surface

temperatures of the planet. With the advent of satellites and

other technology in the last half of the twentieth century,

scientists have been able to more precisely measure the ocean

levels. They have found that sea levels are rising at a rate of

about 0.4–1.2 in (1–2 cm) per year. A 1-ft (30-cm) rise in

sea level would place at least 100 ft (30 m) of beach width

underwater.

Why the earth is heating up is the subject of much

discussion and disagreement among scientists. Some believe

it is due to the heavy burning of

fossil fuels

, such as

coal

and oil, which causes increases the amounts of certain gases,

particularly

carbon dioxide

,inthe

atmosphere

. Other

scientists believe the current global warming is mostly a

natural phenomenon and a part of the normal cycle of the

planet’s environment.

Scientists are studying the ice cap on

Antarctica

to

determine if, in fact, the earth’s

climate

is warming due to

the burning of fossil fuels. The global warming hypothesis is

based on the atmospheric process known as the

greenhouse

effect

, in which

pollution

prevents the heat energy of the

earth from escaping into the outer atmosphere. Global

warming could cause some of the ice caps to melt, raising

the sea level and

flooding

many of the world’s largest cities,

including New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and London, and

other lowland areas. Nearly half of the world’s population

live in coastal areas. Because the polar regions are the engines

that drive the world’s weather system, this research is essen-

tial to identify the effect of human activity on these regions.

Many scientists are concerned about the increasing

levels of

carbon

dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. With more

carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, they say, more heat will

be trapped. Earth’s annual average temperature will begin to

rise. Some estimates suggest that a doubling of atmospheric

carbon dioxide will result in an increase of 4.5°F (2.5°C) in

the planet’s annual average temperature.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sea otter

While that number may seem small, it could have

disastrous effects on the world’s economies. One result might

be the melting of Earth’s ice caps at the North and South

poles, with a resulting increase in the volume of the ocean’s

water. Were that to happen, many of the world’s largest

cities, those located along the edge of the oceans, might be

flooded. Some experts predict dramatic changes in climate

that could turn currently productive croplands into deserts,

and deserts into productive agricultural regions.

As with many environmental issues, experts tend to

disagree about one or more aspects of anticipated climate

change. Some authorities are not convinced that the addition

of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere will have any significant

long-term effects on Earth’s average annual temperature.

Others concede that Earth’s temperature may increase, but

that the changes predicted are unlikely to occur. They point

out that other factors, such as the formation of clouds, might

counteract the presence of additional carbon dioxide in the

atmosphere. They warn that nations should not act too

quickly to reduce the

combustion

of fossil fuels since that

will cause serious economic problems in many parts of the

world. They suggest it would be prudent to wait for a while

to see if greenhouse factors really are beginning to change.

[Ken R. Wells]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Douglas, B. C. ed, et al. Sea Level Rise: History and Consequences. San

Diego: Academic Press, 2000.

P

ERIODICALS

Laber, Emily. “Meltdown.” The Sciences (July 1999): 6.

Middleton, Nick. “The Heat is On.” Geographical (January 2000): 44.

Moore, Curtis A. “Awash in a Rising Sea.”International Wildlife (January–

February 2002).

Spalding, Mark. “Danger on the High Seas.” Geographical (February 2002):

15–16.

Foley, Grover. “The Threat of Rising Seas.” The Ecologist (March–April

1999): 76–79.

O

RGANIZATIONS

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 14th St. and

Constitution Ave. NW, Room 6013, Washington, DC USA 20230

(202)482-6090, Fax: (202)482-3154, Email: answers@noaa.gov, <http://

www.noaa.gov>

Sea lions

see

Seals and sea lions

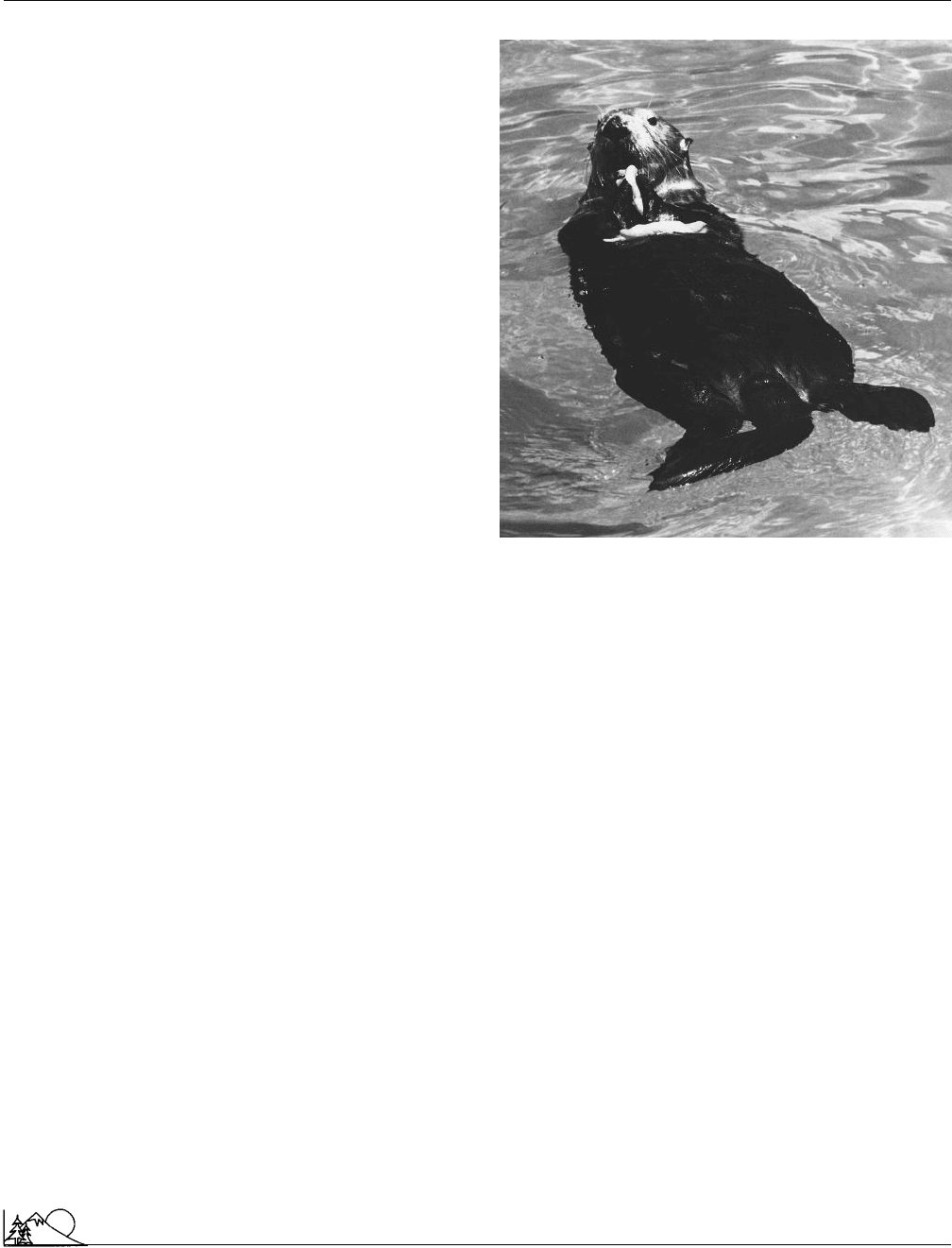

Sea otter

The sea otter (Enhydra lutris) is found in coastal marine

waters of the northeastern Pacific Ocean, ranging from Cali-

1261

A female sea otter eating squid. (Photograph by

Karl W. Kenyon, National Audubon Society Collection.

Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

fornia to as far north as the Aleutian Islands. Sea otters

spend their entire lives in the ocean and even give birth

while floating among the kelp beds. Their ability to use

tools, often “favorite” rocks, to open clam shells and sea

urchins is well-known and fascinating since few other ani-

mals are known to exhibit this behavior. Their playful, curi-

ous nature makes them the subjects of many

wildlife

pho-

tographers but also has aided in their demise. Many are

injured or killed by ship propellers or in fishing nets.

Some sea otters are killed for their highly valued fur.

Their thick hair traps air, insulating the otter from the cold

water in which it lives. Before they were placed under inter-

national protection in 1924, 800,000 to one million sea otters

were slaughtered for their pelts, eliminating them from large

portions of their original range. Despite

poaching

, which

remains a problem, they are slowly returning through reloca-

tion efforts and natural

migration

. Their proximity to hu-

man settlement, however, still poses a problem for their

continued survival.

Pollution

, especially from

oil spills

, is deadly to the

sea otter. The insulating and water-repellant properties of

their fur are inhibited when oil causes the fine hairs to stick

together, and otters die from hypothermia. Ingestion of oil

during grooming does extensive, often fatal, internal damage.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

In 1965, an oil spill near Great Sitkin Island, Alaska, reduced

the island’s otter population from 600 to six. In 1989, the

oil tanker

Exxon Valdez

spilled over 11 million gal (40

million l) of crude oil into

Prince William Sound

, Alaska,

leading to the nearly complete elimination of the Sound’s

once thriving sea otter population. In California, fears that

a similar incident could destroy the sea otter population

there have led to relocation efforts.

Sea otters have few natural enemies, but they were

extensively hunted by Aleuts and later by Europeans. Sea

otters were hunted to

extinction

around several islands in

Alaska, an event that led to studies on the importance of

sea otters in maintaining marine communities. Attu Island,

one of the islands that has lost its otter population, has high

sea urchin populations that have, through their grazing,

transformed a kelp forest into a “bare” hard ground of

coralline and green algae. Few fish or abalone are present

in these waters anymore. On nearby Amchitka Island, otters

are present in densities of 7.7–11.6 per mi

2

(20–30 per km

2

)

and forage at depths up to 22 yd (20 m). In this area, few

sea urchins persist and dense kelp forests harbor healthy fish

and abalone populations. These in turn support higher-order

predators such as

seals

and bald eagles.

Effects of sea otter foraging have also been docu-

mented in soft-bottom communities, where they reduce den-

sities of sea urchins and clams. In addition, disturbance of

the bottom

sediment

leads to increased predation of small

bivalves by sea stars. Otters’ voracious appetite for inverte-

brates also brings them into conflict with people. Fishermen

in northern California blame sea otters for the decline of the

abalone industry. Farther south, residents of Pismo Beach, an

area noted for its clam industry, are exerting pressure to

remove otters. Sea urchin and crab fishermen have also come

into conflict with these competitors. It remains a challenge

for fishermen, environmentalists, and regulators to arrive

at a mutually agreeable management policy that will allow

successful coexistence with sea otters. The sea otter census

of 2001 counted only 2,161 otters in California, less than

6,000 in Alaska, 2,500 in Canada, 555 in Washington, and

about 15,000 in Russia. They are considered endangered by

the IUCN.

[William G. Ambrose Jr. and Paul E. Renaud]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Sumick, J. L. An Introduction to the Biology of Marine Life. 5th ed. Dubuque,

IA: W. C. Brown, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Brazil, Eric. “Annual Census Begins in State for Nearly Extinct Sea Mam-

mal. San Francisco Chronicle (May 18, 2001): A3.

Kvitek, R. G., et al. “Changes in the Alaskan Soft-Bottom Prey Communi-

ties Along a Gradient of Sea Otter Predation.” Ecology 73 (1992): 413–28.

1262

“Northern Sea Otters may be Declared Endangered.” The Grand Rapids

Press (November 12, 2000): A3.

Raloff, J. “An Otter Tragedy.” Science News 143 (1993): 200–202.

O

THER

Help Save the Sea Otters. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.saveseaotters.org>.

Friends of the Sea Otter. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.seaotters.org>.

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society was founded in

1977 by Paul Watson, one of the founding members of

Greenpeace

, as an aggressive direct action organization

dedicated to the international conservation and protection

of marine

wildlife

in general and marine mammals in partic-

ular. The society seeks to combat exploitative practices

through education, confrontation, and the enforcement of

existing laws, statutes, treaties, and regulations. It maintains

offices in the United States, Great Britain, and Canada, and

has an international membership of about 15,000.

Sea Shepherd regards itself virtually as a police force

dedicated to ocean and marine life conservation. Most of

its attention over the years has been devoted to the enforce-

ment of the regulations of the International Whaling Com-

mission (IWC), which makes policies for signatory states

on

whaling

practices but does not itself have powers of

enforcement. The stated objective of the society has been

to harass, interfere with, and ultimately shut down all contin-

uing illegal whaling activities.

Called a “samurai conservation organization” by the

Japanese media, Sea Shepherd often walks a thin line be-

tween legal and illegal tactics. The society operates two

research ships, the Sea Shepherd and the Edward Abbey, and

has been known to ram illegal or pirate whaling ships and

to sabotage whale processing operations. All crew members

are trained in techniques of “creative non-violence:” They

are forbidden to carry weapons or explosives or to endanger

human life and are enjoined to accept all moral responsibility

and legal consequences for their actions.

Crew members also pledge never to compromise on

the lives of the marine mammals they protect. The Society

has documented on film illegal whaling operations in the

former Soviet Union and presented this evidence to the

IWC, despite being chased back to United States waters by

a Soviet frigate and helicopter gunships. Moreover, members

are not at all squeamish about the destruction of weapons,

ships, and other property used in the slaughter of marine

wildlife. In 1979, Sea Shepherd hunted down and rammed

the pirate whaler Sierra, eventually putting it out of business.

Publicity over the Sierra operation motivated the arrest of

two other pirate whalers in South Africa. The next year Sea

Shepherd was involved in the sinking of two Spanish whalers

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sea turtles

that had flagrantly exceeded whale quotas set by the IWC.

In 1986, Sea Shepherd was involved in the sinking of two

Icelandic whalers (half the Icelandic whaling fleet) in Reyk-

javik harbor and also managed to damage the nearby whale-

processing plant. Seeking publicity, crew members de-

manded to be arrested for their actions, but Iceland refused

to charge them. Indeed, Sea Shepherd claims that in all of

its operations it has never caused nor suffered an injury, nor

have any of its crew members been convicted in criminal

proceedings.

Typically, Sea Shepherd invites members of the news

media along to document and publicize the destructive and

exploitative practices it opposes. Such documentary footage

has been shown on major television networks in the United

States, Britain, Canada,

Australia

, and Western Europe.

This publicity played an important role in increasing public

awareness of marine conservation issues and in mobilizing

public opinion against the slaughter of marine mammals.

Sea Shepherd helped to bring about the end of commercial

seal-killing in Canada and in the Orkney Islands, Scotland.

Highly successful in its efforts against outlaw whalers,

Sea Shepherd continues to conduct research on conservation

and

pollution

issues and to monitor national and interna-

tional law on marine conservation issues. Its members are

working to establish a wildlife sanctuary in the Orkney

Islands. Its present campaign is focused primarily against drift

netfishing in the NorthPacific, in support ofa United Nations

call for a complete international ban on drift-net fishing.

[Lawrence J. Biskowski]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, 22774 Pacific Coast Hwy., Malibu,

CA USA 90265 (310) 456-1141, Toll Free: (310) 456-2488, <http://

www.seashepherd.com>

Sea turtles

Sea turtle populations have dramatically declined in numbers

over the past half century. Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas),

hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata), Kemp’s Ridleys (Lepido-

chelys kempii), loggerheads (Caretta caretta), and leatherbacks

(Dermochelys coriacea) have all had their numbers decimated

by human activity. The decline has been caused by several

factors, including the development of a highly industrialized

fishery to meet the demand for seafood on a worldwide

basis. The most economical fishing method involves pulling

multiple nets underwater for extended periods of time, and

any air-breathing animals, such as sea turtles, which get

caught in the net are usually drowned before they are hoisted

on board.

1263

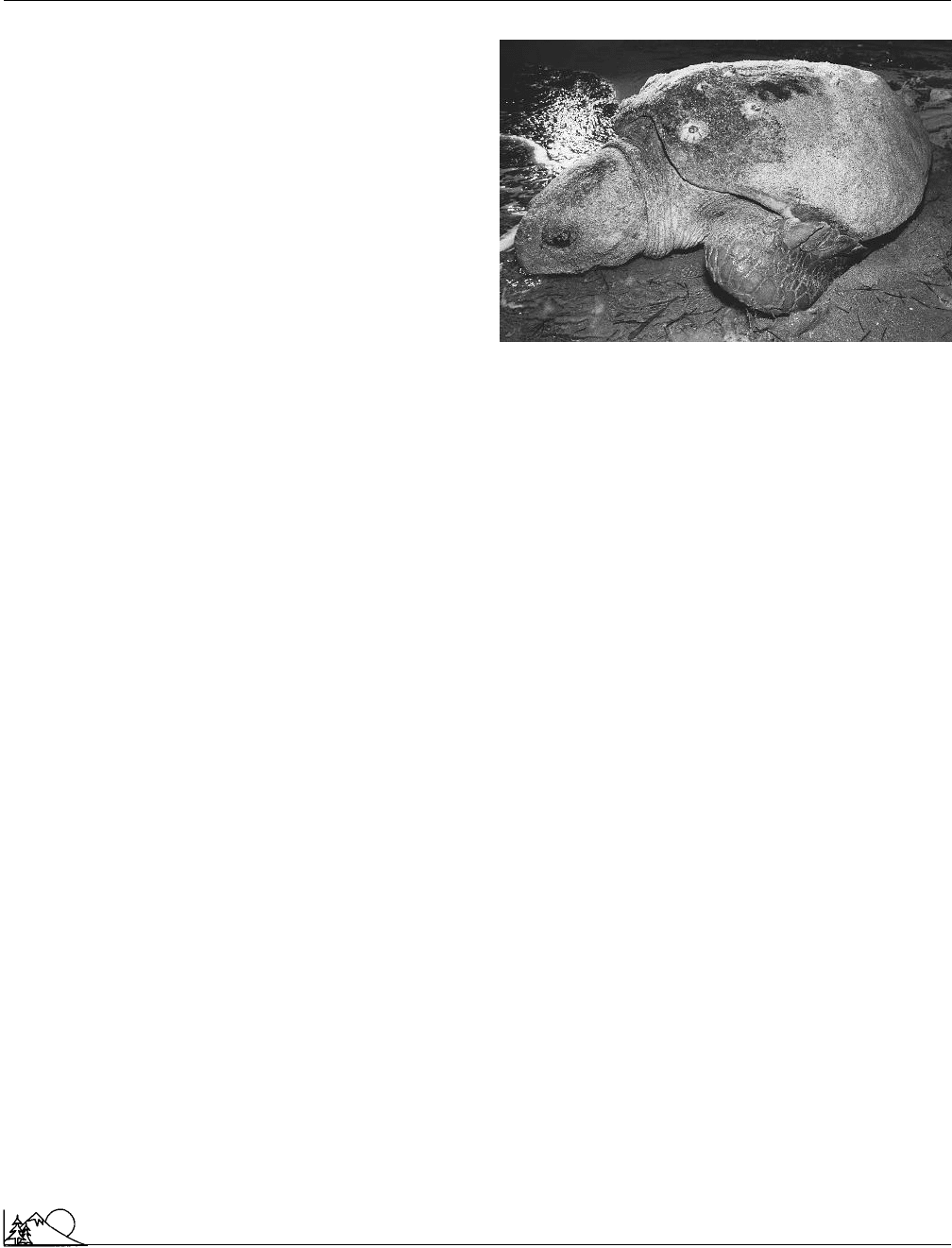

Loggerhead sea turtle returns to sea after lay-

ing eggs on a Florida beach. (Corbis-Bettmann. Re-

produced by permission.)

In the United States, this problem has led to the

introduction of the

turtle excluder device

(TED), which

must be placed on each tow net used by commercial shrimp-

ers and fishermen. These cage-like devices have a slanted

section of bars which allow fish and shellfish into the net

but deflect turtles. These highly controversial devices have

been mandatory for less than a decade, but there are some

indications that they are saving thousands of turtles per year.

As significant as the impact of

commercial fishing

may seem, it does little to sea turtle populations compared

to losses incurred at the earliest stages of the turtles’ life

history. In the late 1940s, along an isolated beach near

Tamaulipas, Mexico, an extremely dense assemblage of sea

turtles were observed digging out nests and laying eggs at

the beach. So many females were present that they were

seen crawling over one another and digging out the nests

of others in order to lay their own eggs. At this location

alone, the sea turtle population was estimated in the millions.

In the early 1960s, scientists realized that the turtles found

at Tamaulipas were a distinct

species

, Kemp’s Ridley, and

that they nested nowhere else in the world; but by that time

the population had declined to only a few hundred turtles.

Threats to the survival of newly hatched sea turtles

have always been enormous; crows, gulls, and other predators

attack them as they scurry seaward, and they are prey for

waiting barracudas and jacks as they reach water. Other

animals raid their nests for the eggs, and humans are among

these nest predators, collecting the eggs for food. Sea turtles

concentrate their numbers in small nesting locations such

as Tamaulipas in order to greatly outnumber their natural

predators, thus allowing for the survival of at least a few

individuals to perpetuate the species. However, this congre-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Seabed disposal

A green sea turtle. (Photograph by Dr. Paula A. Zahl.

Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

gating behavior has contributed to their demise, because it

has made human predation easier and more profitable.

Adult turtles are harvested as a protein source in many

Third World

countries, and many turtles are also subjected

to increasing levels of

marine pollution

. Both of these fac-

tors have contributed to the sharp decline in their population.

Public awareness and

conservation

efforts may keep sea

turtles from

extinction

, but it is not clear whether species

will be capable of rebounding from the decimation that has

already taken place.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bjorndal, K. A., ed. Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles. Washington,

D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981.

Carr, Archie. So Excellent a Fish: Tales of Sea Turtles. New York: Scribn-

ers, 1984.

National Research Council. Decline of the Sea Turtles: Causes and Prevention.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Ezell, C. “Turtle Recovery Could Take Many Decades.” Science News 142

(August 22, 1992): 118.

“Sea Turtle Nesting Begins Soon.” The Florida Times Union (April 13,

2002): L–13.

1264

Stolzenburg, W. “Requiem for the Ancient Mariner.” Sea Frontiers 39

(March–April 1993): 16–18.

O

THER

National Marine Fisheries Service. [cited May 2002]. <http://

www.nmfs.noaa.gov>.

Seabed disposal

Over 70% of the earth’s surface is covered by water. The

coastal zone—the boundary between the ocean and land—

is under the primary influence of humans, while the rest of

the ocean remains fairly remote from human activity. This

remoteness has in part led scientists and policy makers to

examine the deep ocean, particularly the seabed, as a poten-

tial location for waste disposal.

Much of the deep ocean seabed consists of abyssal

hills and vast plains that are geologically stable and have

sparse numbers of bottom-dwelling organisms. These areas

have been characterized as oozes, hundreds of meters thick,

that are in effect “deserts” in the sea. Other attributes of the

deep ocean seabed that have led scientists and policy makers

to consider the sea bottom as a repository for waste include

the immobility of the interstitial pore water within the

sedi-

ment

, and the tendency for ions to adsorb or stick to the

sediment, which limits movement of elements within the

waste. Another important factor has been the lack of known

commercial resources such as

hydrocarbons

, minerals, or

fisheries.

The deep seabed has been studied as a potential dis-

posal option specifically for the placement of

high-level

radioactive waste

. Investigations on the feasibility of dis-

posing radioactive wastes in the seabed were carried out for

over a decade by a host of scientists from around the world.

In 1976, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development (OECD) and the Nuclear Energy Agency

coordinated research at the international level and formed

the Seabed Working Group. Members of the group included

Belgium, Canada, France, the Federal Republic of Germany,

Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, United Kingdom,

United States, and the Commission of European Communi-

ties. The Seabed Working Group focused its investigation

on two sites in the Atlantic Ocean, Great Meteor East and

the Southern Nares Abyssal Plain, and one site in the Pacific

Ocean, known as E2. The Great Meteor East site lies be-

tween 30.5°N and 32.5°N, 23°W and 26°W, approximately

1,865 mi (3,000 km) southwest of Britain. The Southern

Nares Abyssal Plain site lies between 22.58°N and 23.17°N,

63.25°W and 63.67°W, approximately 375 mi (600 km)

north of Puerto Rico. Site E2 in the Pacific Ocean lies

between 31.3°N and 32.67°N, 163.42°E and 165°E, and is

approximately 1,240 mi (2,000 km) east of Japan.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Seabed disposal

This working group pursued a multidisciplinary ap-

proach to studying the deep-ocean sediments as a potential

disposal option for high-level

radioactive waste

. High-

level radioactive waste consists of spent nuclear fuel or by-

products from the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel. It also

includes transuranic wastes, a byproduct of fuel assembly,

weapons fabrications, and reprocessing operations, and

ura-

nium

mill

tailings

, a byproduct of mining operations.

Low-

level radioactive waste

is legally defined as all types of

waste that do not fall into the high-level radioactive waste

category. They are made up primarily of byproducts of nu-

clear reactor operations and products that have been in con-

tact with the use of radioisotopes. Low-level radioactive

wastes are characterized as having small amounts of

radioac-

tivity

that do not usually require shielding or heat-removing

equipment.

One proposal to dispose of high-level radioactive waste

in the deep seabed involved the enclosure of the waste in

an insoluble solid with metal sheathing or projectile-shaped

canisters. When dropped overboard from a ship, the canisters

would fall freely to the ocean bottom and bury themselves

33–44 yd (30–40 m) into the soft sediments of the seabed.

Other proposals recommend drilling holes in the seabed and

mechanically inserting the canisters. After emplacement of

the canisters, the holes would then be plugged with inert

material.

The 1972 international

Convention on the Preven-

tion of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Waste and Other

Matter

, commonly called the London Dumping Conven-

tion, prohibits the disposal of high-level radioactive wastes.

In the United States, the

Marine Protection, Research and

Sanctuaries Act

of 1972 also bans the ocean disposal of

high-level radioactive waste. However, Britain has recently

considered using the continental shelf seabed for disposal of

low- and intermediate-level radioactive waste. The Euro-

pean countries discontinued

ocean dumping

of low-level

radioactive waste in 1982. In the United States, the ocean

disposal of low-level radioactive waste ceased in the 1970s.

Between 1951 and 1967, approximately 34,000 containers

of low-level radioactive waste were dumped in the Atlantic

Ocean by the United States.

Another important aspect in the debate about seabed

disposal is the risk to humans, not only because of the

potential for direct contact with wastes but also because of

the possibility of accidents during transport to the disposal

location and contamination of fishery resources. When com-

paring seabed disposal of high-level radioactive waste to

land disposal, for example, the

transportation

risks may be

higher because travel to a site at sea would likely be longer

than travel to a location on land. Increased handling by

personnel substantially increases the risk. Also, there is a

statistically greater risk of accidents at sea than on land

1265

when transporting anything, especially radioactive wastes,

although such an accident at sea would probably pose less

risk to humans.

It is also a concern that the seabed

environment

may

be more inhospitable than a land site to the metal canisters

containing the radioactive waste, because corrosion is more

rapid due to the salts in marine systems. In addition, it is

uncertain how fast

radionuclides

will be transported away

from the site. The heat associated with the decay of high-

level radioactive waste may cause convection in the sediment

pore waters, resulting in the possibility that the dissolved

radioactive material will diffuse to the sediment-water inter-

face. Predictions from calculations, however, indicate that

convection may not be significant. According to laboratory

experiments that simulate subseabed conditions, it would

take roughly 1,000 years for radioactive waste buried at a

depth of 33 yd (30 m) to reach the sediment-water interface.

Other technical considerations adding to the uncertainty of

the ultimate fate of buried radioactive waste in the seabed

involve possible

sorption

of the radionuclide cations to clay

particles in the sediment, and possible uptake of radionu-

clides by bottom dwelling organisms.

The Seabed Working Group concluded from their

investigation that seabed disposal of high-level radioactive

waste is safe. Compared to land disposal sites, the predicted

doses of possible

radiation exposure

are lower than pub-

lished radiological assessments. However, there are political

concerns over deep-ocean seabed disposal of wastes. Deep-

ocean disposal sites would likely be in international waters.

Therefore, international agreements would have to be

reached, which may be very difficult with countries without

a

nuclear power

industry, particularly for disposal of radio-

active waste.

In 1991, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

held a workshop to discuss the research required to assess

the potential of the abyssal ocean as an option for disposal

of sewage

sludge

, incinerator ash, and other high volume

benign wastes. The disposal technology considered at this

workshop entailed employing an enclosed elevator from a

ship to emplace the waste at or close to the seabed. One

issue raised at the workshop was the need to investigate the

incidence of benthic storms that may occur along the deep

ocean seabed. These benthic storms, also called turbidity

flows, are currents with high concentrations of sediment that

can stir up the sea bottom, erode the seabed, and redistribute

sediment further downstream.

Woods Hole held a follow-up workshop in 1992. In-

cluded were a broader array of scientists and representatives

from environmental organizations, and these two groups

disagreed over the use of the ocean floor as a waste-disposal

option. The researchers supported the consideration and

study of the seabed and the ocean in general as sites for

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Seabrook Nuclear Reactor

disposal of wastes. The environmentalists did not support

ocean disposal of wastes. The environmentalists’ view is

consistent with the law passed in 1988, the

Ocean Dumping

Ban Act

, which prohibits the dumping of sewage sludge and

industrial waste in the marine environment. In 1993, a ban

on the dumping of any radioactive materials into the sea

was put into effect at the London Convention and will be

enforced until 2018. See also Convention on the Law of the

Sea; Dredging; Hazardous waste siting; Marine pollution;

Ocean dumping; Radioactive pollution

[Marci L. Bortman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Chapman, N. A., and I. G. McKinley. The Geological Disposal of Nuclear

Waste. New York: Wiley, 1987.

Freeman, T. J., ed. Advances in Underwater Technology, Ocean Science and

Offshore Engineering. Vol. 18, Disposal of Radioactive Waste in Seabed Sedi-

ments. Boston: Graham & Trotman, 1989.

Krauskopf, K. B. Radioactive Waste Disposal and Geology. New York: Chap-

man and Hall, 1988.

Murray, R. L. Understanding Radioactive Waste. Ed. Judith A. Powell.

Columbus, OH: Battelle Press, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Spencer, D. W. “The Ocean and Waste Management.” Oceanus 33 (Summer

1990): 7–23.

Seabrook Nuclear Reactor

Americans once looked to nuclear energy as the nation’s

great hope for power generation in the twenty-first century.

Today, nuclear

power plants

are regarded with suspicion

and distrust, and new proposals to construct them are met

with opposition. Perhaps the best transition in the perception

of

nuclear power

is the debate that surrounded the con-

struction of the Seabrook Nuclear Reactor in Seabrook, New

Hampshire.

The plant was first proposed in 1969 by the Public

Service Company of New Hampshire (PSC), an agency then

responsible for providing 90% of all electrical power used in

that state. The PSC planned to construct a pair of atomic

reactors in marshlands near Seabrook in order to ensure an

adequate supply of electricity in the future.

Residents were not enthusiastic about the plan. The

marshlands and beaches around Seabrook have long been a

source of pride to the community, and in March of 1976,

the town voted to oppose the plant. Townspeople soon

received a great deal of support. Seabrook is only a few

miles north of the Massachusetts border, and residents and

1266

government officials from that state joined the opposition

against the proposed plant. In addition, an umbrella organi-

zation of 15 anti-nuclear groups called the Clamshell Alli-

ance was formed to fight the PSC plan.

The next 12 years were characterized by almost non-

stop confrontation between the PSC and its supporters and

Clamshell Alliance and other groups opposed to the proposal.

Hardly a month passed during the 1970s and 80s without

news of another demonstration or the arrest of someone pro-

testing construction. The issues became more complex as eco-

nomic and technical considerations changed during this time.

The demand for electricity, for example, began to drop instead

of increasing, as the PSC had predicted, and at least three

other utilities that had agreed to work with PSC on construc-

tion of the plant withdrew from the program. The total cost

of construction also continued to rise. When first designed,

construction costs were estimated at $973 million for both

reactors. Only one reactor was ever built, and by the time that

it was finally licensed in 1990, total expenditures for it alone

had reached nearly $6.5 billion.

The decision to build at Seabrook eventually proved

to be a disaster financially and from a public relations stance

for PSC. The company’s economic woes peaked in 1979

when the courts ruled that PSC could not pass along addi-

tional construction costs at Seabrook to its customers. Over

the next decade, the company fell into even more difficult

financial straits, and on January 28, 1988, it filed for bank-

ruptcy protection. The company promised that its action

was not the end for the Seabrook reactor and maintained

that the plant would eventually be licensed.

A little more than two years later, the

Nuclear Regu-

latory Commission

(NRC) granted a full-power operating

license to the Seabrook plant. The decision was received

enthusiastically by the utility companies in the New England

Power Pool, who believed that Seabrook’s additional capacity

would reduce the number of power shortages experienced

by consumers in the six-state region.

Private citizens and government officials were not as

enthusiastic. Consumers faced the prospect of higher electri-

cal bills to pay for Seabrook’s operating costs, and many

observers continued to worry about potential safety prob-

lems. Massachusetts attorney general, James Shannon, for

example, was quoted as saying that Seabrook received “the

most legally vulnerable license the NRC has ever issued.”

As of July 2002, Seabrook was operating at 100%

power and providing electricity for over one million homes.

See also Electric utilities; Energy policy; Nuclear fission;

Radioactive waste management; Three Mile Island Nuclear

Reactor

[David E. Newton]