Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sharks

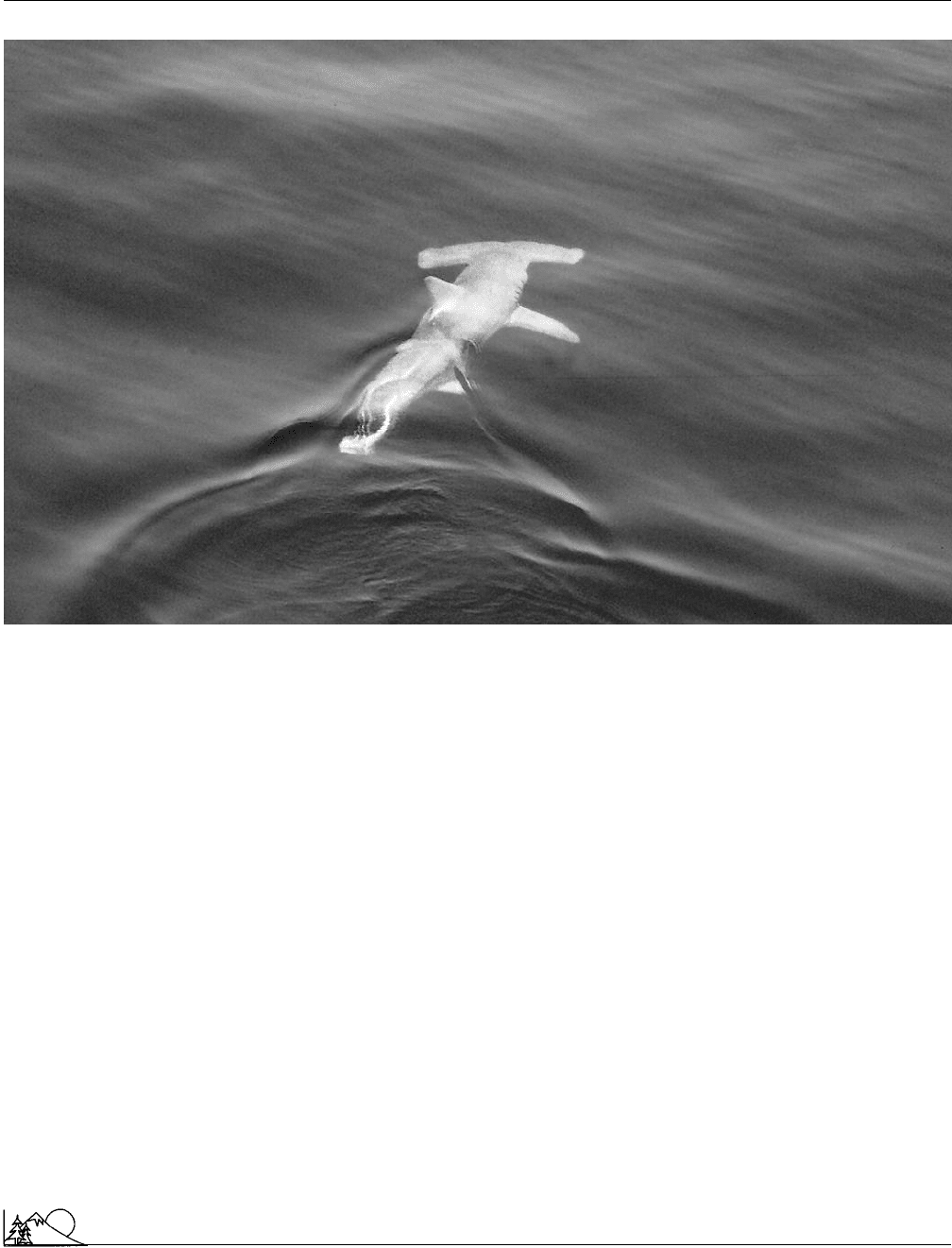

A hammerhead shark swimming just below the water surface. (Photograph by John Bortniak, NOAA Corp. National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

is a potential danger to swimming or surfing humans. The

species most often linked with attacks on people are the great

white shark, the tiger shark, and the bull shark (Carcharhinus

leucas). These are all widely distributed species that are

adapted to feeding on

seals

or

sea turtles

, but may also

opportunistically attack humans.

According to data compiled by the International Shark

Attack File, in the year 2001 there were about 76 unprovoked

shark attacks on humans world-wide. This included 54 at-

tacks in U.S. waters, mostly occurring off beaches in Florida.

(This tally does not include “provoked” attacks, as might

happen when a fisher is attempting to remove an entangled

shark from a net or hook, or scavenging damage done to an

already-drowned human.) Only five of those unprovoked

attacks, however, resulted in fatalities (three were in the

United States). This relatively low, 7% fatality rate is thought

to occur because, from the perspective of the shark, an attack

on a human is usually a “mistake” that happens when a

swimmer or surfer is confused with a more usual prey animal,

1287

such as a seal. In such cases, the shark usually breaks off the

attack before lethal damage.

Although there is always a risk of being attacked by

a large shark while swimming or surfing in waters that they

frequent, the actual

probability

of this happening is ex-

tremely small. In the United States, for example, many more

human fatalities are caused by bee and wasp stings and by

venomous snakebites. Even lightning strikes cause about 30

times as many deaths per year as do shark attacks. In fact,

it is much more dangerous to drive to and from a beach in

the United States, compared to the risk of a shark attack

while swimming there.

Although it is a fact that very few humans are hurt

by sharks each year, the reverse is definitely not true. Sharks

are extremely vulnerable to fishing pressure because of their

slow growth rate, length maturation period, and low birth

rate. Consequently,

commercial fishing

practices are devas-

tating populations of many species of sharks throughout the

oceans of the world. In waters of the United States, for

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Paul Howe Sheppard

example, fishing

mortality

of sharks in recent years has been

equivalent to about 18-thousand tons (20-thousand tonnes)

per year. This is much more than the maximum sustainable

yield calculated by fishery scientists, which is equivalent to

about 9–11-thousand tons (10–15-thousand tonnes) per

year. Because of this intense

overfishing

, there has been a

catastrophic decline in the numbers of sharks in U.S. territo-

rial waters, by as much as 80% since the 1970s and 1980s.

A similar decrease is also occurring in many other regions

of the world, and for the same reasons.

The excessive killing of sharks is occurring for several

reasons. Some species of sharks, such as the spiny dogfish,

are commercial species caught for their meat. Larger species

of sharks may be caught in large numbers solely for their

fins, which are cut off and sold as a delicacy in certain Asian

markets, particularly in China. Shark “finning” is a widely

illegal but common practice. It is also extremely wasteful as

the de-finned sharks are thrown back into the sea, either as

dead carcasses or as live fish doomed to starve to death

because they are incapable of swimming properly. As many

as 30–100 million sharks may be subjected to this finning

practice each year. There are also economically significant

recreational fisheries for sharks, involving sportsmen catch-

ing them as trophies.

In addition to sharks being targets of commercial and

recreational fisheries, immense numbers are also incidentally

caught as so-called “bycatch” in fisheries targeted for other

species of fish. This is especially the case in long-line fisheries

for large tuna and

swordfish

. This open-ocean fishing

method, mostly practiced by boats fishing for Japan, Korea,

and Taiwan, involves setting tens of miles of line containing

thousands of baited hooks. This is a highly non-selective

practice that kills enormous numbers of species that are not

the intended target of the fishery, including many sharks.

Some fishery biologists believe that the

bycatch

mortality

of sharks, about 12-million animals per year, may be at least

half the size of the commercial fishery of these animals. This

excessive bycatch of sharks, almost all of which is discarded

at sea as “waste,” is further contributing to the devastation

of their populations. The World Conservation Union

(IUCN) lists numerous species of sharks as being at risk of

endangerment or

extinction

.

In a few places, sharks are contributing to the local

economy in ways that do not require the destruction of these

marvelous animals. This is happening through

ecotourism

involving recreational diving with sharks in non-threatening

situations. For instance, waters off Cocos Island, Costa Rica,

sustain large numbers of whitetip reef sharks (Triaenodon

obesus), hammerheads (Sphyrna zygaena), and whale sharks

(Rhincodon typus), and this is a local attraction for scuba-

diving tourists.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

1288

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Compagno, L. J. V. Sharks of the World. New York: UN Food and Agricul-

tural Organization and UN Development Programme, 1984.

Springer, V. G., and J. P. Gold. Sharks in Question: The Smithsonian Answer

Book. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Stevens, J. D., ed. Sharks. New York: Facts on File Publications, 1987.

O

THER

Public Broadcasting Service. The World of Sharks. [cited July 2002]. <http://

www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sharks/world>.

Shark Specialist Group. [cited July 2002].<http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/

Organizations/SSG/SSGDefault.html>.

The Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.pela-

gic.org>.

The University of Florida. The International Shark Attack File. [cited July

2002]. <http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Sharks/ISAF/ISAF.htm>.

Sheet erosion

see

Erosion

Paul Howe Sheppard (1925 – 1996)

American environmental theorist

A scientist, teacher, and environmental theorist, Shepard

moved beyond the factual realm of biological science to

expand upon the nature of human behavior and its roots in

the natural world. He was a prolific writer who have had a

profound influence on a variety of contemporary thinkers.

In his introduction to The Subversive Science: Essays

Toward an Ecology of Man, edited with Daniel McKinley,

Shepard discussed the reluctance of modern (as opposed to

primitive) people to view humanity as one element of the

whole of creation. Instead, humanity is wrongly seen as

the singular focus or the intended culmination of creation,

thereby denying the role played by all other life forms in

the

evolution

of humankind. Shepard suggested this need

to dominate has led to physical and mental separation from

the whole, resulting in innumerable problems for hu-

mankind, among them

environmental degradation

.He

believed that people should simultaneously appreciate the

integrity of every being as well as the relatedness of all things,

acquiring a world view that is inclusive and holistic rather

than exclusive and superficially hierarchical: “Without losing

our sense of a great human destiny and without intellectual

surrender, we must affirm that the world is a being, a part

of our own body.”

Shepard continued to assess and emphasize the rela-

tionships between other living things and human develop-

ment, particularly the role played by animals. In The Others:

How Animals Made Us Human, he discusses the paradox of

people who both love and kill or hunt animals, and contrasts

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Shoreline armoring

them with those who would protect the “others” of the

natural world from humans in the name of “animal rights:”

“In the perspective of the enormous history of life and the

role of animals in human evolution for a million years, I feel

only disconnected by the precept of untouchability...Great

naturalists and primal peoples were motivated not by the

ideal of untouchability but by a cautious willingness to con-

sume and be consumed, both literally and in a mythic sense.”

Shepard was born on July 12, 1925, in Kansas City,

Missouri; his father was a horticulturist. During World War

II he served in the U.S. Army from 1943–46, in the Euro-

pean theater. He received his B.A. from the University of

Missouri (1949) and his M.S. in

conservation

(1952). His

Ph.D. from Yale (1954) was based on an interdisciplinary

study of

ecology

, landscape architecture, and art history.

Shepard was a Fulbright senior research scholar in New

Zealand in 1961, and later received both a Guggenheim

fellowship to research the cultures of hunting-gathering peo-

ples (1968–69) and a Rockefeller fellowship in the humani-

ties (1979).

For 21 years Shepard taught concurrently at Pitzer

College and Claremont Graduate School (both in Clare-

mont, California), serving as the Avery Professor of Natural

Philosophy and

Human Ecology

at Claremont from 1973

until his retirement in 1994. Earlier he had taught at other

schools, including Knox College, Dartmouth College, and

Smith College. He published numerous books, was a regular

contributor to Landscape and North American Review, and

also wrote for BioScience, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine,

and School Science and Mathematics.

[Ellen Link]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Contemporary Authors. Vol. 10. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983.

Shepard, Paul. Environmental: Essays on the Planet as a Home. Boston:

Houghton, 1971.

———. Man in the Landscape: A Historic View of the Esthetics of Nature.

New York: Knopf, 1967.

———. Nature and Madness. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1982.

———. The Others: How Animals Made Us Human. Washington, D.C.:

Island Press, 1996.

———. The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game. New York:

Scribner, 1973.

———. Thinking Animals: Animals and the Development of Human Intelli-

gence. New York: Viking Press, 1978.

———, and B. Sanders. The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth and

Literature. New York: Viking Press, 1983.

———, and D. McKinley, eds. The Subversive Science: Essays Toward an

Ecology of Man. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969.

———, ed. The Only World We’ve Got: A Paul Shepard Reader. San Fran-

cisco: Sierra Club Books, 1996.

Oelschlaeger, M., ed. The Company of Others: Essays in Celebration of Paul

Shepard. Durango, Co: Kivaki Press, 1995.

1289

P

ERIODICALS

Pace, E. “Paul Shepard, Professor and Author, 71.” New York Times, July

22, 96: A15(L).

Shifting cultivation

Shifting cultivation refers to a practice whereby a tract of

land is alternately used for crop production and then allowed

to return to native vegetation for a period of years. Typically,

the land is cleared of vegetation, crops are grown for two

or three years, and then the land abandoned for a period of

10 or more years. To facilitate land clearing prior to cultiva-

tion, the vegetation is cut and the debris burned. The practice

is also called slash-and-burn agriculture or swidden agri-

culture.

Shifting cultivation is most common in the tropics

where farming techniques are less technologically advanced.

The soils are usually low in plant nutrients. For two or three

years following land clearing, the nutrients brought to, or

near, the

soil

surface by deep rooting trees, shrubs, and other

plants support cultivated crops. With native management,

the available nutrients are removed by the cultivated crops

or leached so that after a few years the soil will support only

minimal plant growth. It is then allowed to return to native

vegetation which slowly concentrates the nutrients in the

surface soil again. After a period of years the cycle repeats.

Erosion

is often severe on sloping land during the cultivated

phase. On some soils, particularly in the tropics, the soil

structure becomes massive and hard. See also Leaching; Soil

compaction; Soil organic matter

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ramakrishnan, P. S. Shifting Agriculture and Sustainable Development: An

Interdisciplinary Study from North-Eastern India. Park Ridge, NJ: Parthenon

Publishing Group, 1992.

Vasey, D. E. An Ecological History of Agriculture. Ames, IA: Iowa State

University Press, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Monastersky, R. “Legacy of Fire: The Soil Strikes Back.” Science News 133

(April 9, 1988): 231.

Shoreline armoring

Shoreline armoring is the construction of barriers or struc-

tures for the purpose of preventing coastal

erosion

and/or

manipulating ocean currents. Although they may prevent

the deterioration of the immediate shoreline, these man-

made structures almost always exacerbate erosion problems

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sick Building Syndrome

at nearby, downstream beaches by changing wave patterns

and water flow.

Armoring may also promote the loss of shoreline vege-

tation, which in turn can degrade the

ecosystem

that sea-

birds and other beach and sea-dwelling life depend upon. By

altering water flow and erosion and deposition and creating

physical barriers, some types of shoreline armoring prevent

sea turtles

from reaching their nesting sites on shore. Fi-

nally, shoreline structures can block sunlight imperative to

aquatic plants such as

eelgrass

, a prime

habitat

for herring

and other marine life.

Shoreline erosion is a natural process determined by

a complex array of environmental causes. Weather changes,

tidal currents, and sea level adjustments all impact erosion

over time. Catastrophic weather events such as hurricanes,

tsunamis

, and tropical storms can completely change the

shape and nature of the coast in one fell swoop. Beach

location, currents, and other conditions may also create de-

positional shorelines, where sand and

sediment

collect

rather than erode. Armoring is a human attempt to minimize

the impact of these natural forces on an isolated section of

coastal shoreline. Because the coastal ecosystem is extensive

and interconnected, these attempts ultimately affect other

nearby, unprotected locations.

Common types of shoreline armoring include

O

Groins. Long barriers that run perpendicular from the

shoreline and are designed to trap sand and deposit it on

the adjacent beach.

O

Jetties. Similar to groins, jetties are rock structures that are

built out from the shoreline. They are often erected for

the purpose of keeping ship or boating channels clear of

sediment build up by directing currents appropriately.

O

Seawalls. These concrete or rock walls act as a barrier

between beach and ocean; but increase neighboring beach

erosion by deflecting normal wave patterns.

O

Bulkheads. Like a seawall, a bulkhead is designed to separate

the also promotes erosion further downstream.

O

Revetments. A small seawall barrier, often constructed from

rocks or boulders.

O

Breakwaters. Breakwaters are offshore structures that ab-

sorb much of the force of waves before they reach the

shoreline. They sometimes serve a dual purpose as naviga-

tional aids in boating channels.

O

Rip Rap. Rip rap is a rock armoring sometimes used on

river beds as well as coastal slopes to deter erosion.

O

Docks. Although they are not built for the purpose of pre-

venting coastal erosion, boat dock structures do impact

marine life by blocking sunlight crucial for vegetation. Pil-

ings, or posts, for docks can also disrupt sea-floor sedi-

ments. Depending on their size, structure, and location,

they can also influence natural water flow patterns.

1290

Alternatives to shoreline armoring include main-

taining or planting native coastal shrubs, trees, and other

plants that have an established root system to help prevent

erosion.

Beach renourishment

, the process of replacing

eroded beach with dredged offshore sand, is also used for

erosion management. However, renourishment is cost-pro-

hibitive in many cases, and may have a negative impact on

marine

flora

and

fauna

. It also requires ongoing mainte-

nance, as erosion is a perpetual process. Finally, the reloca-

tion of structures placed at risk by severe erosion, sometimes

referred to as a retreat strategy, allows the natural processes of

shoreline

evolution

to continue while preserving the public

interest.

Shoreline armoring is becoming more widely recog-

nized as an environmental hazard rather than a help. In

South Carolina, state legislation entitled the 1988

Beachfront Management Act established a retreat rather

than armor strategy for dealing with shoreline changes. The

Act states that “[t]he use of armoring in the form of hard

erosion control devices such as seawalls, bulkheads, and rip

rap to protect erosion-threatened structures adjacent to the

beach has not proven effective. These armoring devices have

given a false sense of security to beachfront property owners.

In reality, these hard structures, in many instances, have

increased the vulnerability of beachfront property to damage

from wind and waves while contributing to the deterioration

and loss of the dry sand beach which is so important to

the tourism industry.” South Carolina no longer allows the

construction of shoreline armoring within its coastal set-

back area, nor the rebuilding of existing armoring that is

more than two-thirds damaged.

[Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dean, Cornelia. Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s Beaches. New

York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Dunn, Steve, et al. “Coastal Erosion: Evaluating the Risk.” Environment

42, no. 7 (September 2000): 36 (10).

O

THER

South Carolina General Assembly. Beachfront Management Act of 1988.

S.C. Code of Regulations. Chapter 30, Section 48-39-320(B). 1998 [cited

June 6, 2002]. <http://www.lpitr.state.sc.us/coderegs/c030.htm#30-21>.

Sick Building Syndrome

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) is a term applied to a building

that makes its occupants sick because of indoor air pollutants.

Indoor air quality

(IAQ) problems fall into three categories:

SBS, building-related illnesses, and

multiple chemical sen-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sierra Club

sitivity

. Of the three, SBS accounts for 75% of all IAQ

complaints.

Indoor air is a health hazard in 30% of all buildings,

according to the World Health Organization. The

Environ-

mental Protection Agency

(EPA) lists IAQ fourth among

top

environmental health

threats. The problem of SBS is

of increasing concern to employees and occupational health

specialists, as well as landlords and corporations who fear

the financial consequences of illnesses among tenants and

employees.

Respiratory diseases

attributed to SBS account

for about 150 million lost work days each year, $59 billion

in indirect costs, and $15 billion in medical costs.

Sick building syndrome was first recognized in the

1970s around the time of the energy crisis and the move

toward

conservation

. Because heating and air conditioning

systems accounted for a major portion of energy consump-

tion in the United States, buildings were sealed for

energy

efficiency

. Occupants depend on mechanical systems rather

than open windows for outside air and ventilation. A tight

building, however, can seal in and create contaminants.

Common complaints of SBS include headaches, fatigue,

cough, sneezing, nausea, difficulty concentrating, bleary eyes,

and nose and throat irritations. Symptoms are caused by a

range of contaminants, including volatile organic compounds

(VOC), which are

chemicals

that turn to gas at room tem-

perature and are given off by paints, adhesives, caulking,

vinyl, telephone cable, printed documents, furniture, and

solvents. Most common VOCs are

benzene

and chloro-

form, both of which may be carcinogens. Formaldehyde in

building materials also is a culprit.

Biological agents such as viruses, bacteria, fungal

spores, algae, pollen, mold, and dust mites add to the prob-

lems. These are produced by water-damaged carpet and

furnishing or standing water in ventilation systems, humidi-

fiers, and flush

toilets

.

Carbon dioxide

levels increase as the number of peo-

ple in a room increases, and too much can cause occupants

to suffer hyperventilation, headaches, dizziness, shortness of

breath, and drowsiness, as does

carbon monoxide

and the

other

toxins

from

cigarette smoke

.

Schoolchildren are considered more vulnerable to SBS

because schools typically have more people per room breath-

ing the same stale air. Their size, childhood allergies, and

asthmas add to their vulnerability.

Sick buildings can be treated by updating and cleaning

ventilation systems regularly and using air cleaners and

filtra-

tion

devices. Also, plants spaced every 100 ft

2

(9.3 m

2

)in

offices, homes, and schools have been shown to filter out

pollutants in recycled air.

A simple survey of the indoor

environment

can detect

many SBS problems. Check each room for an air source; if

windows cannot be opened, every room should have a supply

1291

vent and exhaust vent. Clean the vents. Check to see if air

is circulating by placing a strip of tissue at each vent opening.

The tissue should blow out at a supply vent and blow in at

an exhaust vent. Move partitions, file cabinets, and boxes

away from vents. Supply and exhaust vents should be more

than a few feet apart. Dead spaces where air stagnates and

pollutants build up should be renovated. Move printing and

copying machines away from people and give those machines

adequate exhaust. Check that the ventilation system operates

fully in every season and whenever people are in the building.

The EPA enforces tough laws on outdoor

air pollu-

tion

, but not for indoor air except for some smoking bans.

Yet almost every pollutant, according to the EPA, is at higher

levels indoors than out. Help in detecting and correcting sick

building syndrome is available from the

National Institute

of Occupational Safety and Health

, the federal agency

responsible for conducting research and making recommen-

dations for safe and healthy work standards. See also Occupa-

tional Safety and Health Administration (OSHA); Occupa-

tional Health and Safety Act

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Kay, J. G., et al. Indoor Air Pollution: Radon, Bioaerosols, and VOCs. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1991.

Samet, J. M., and J. D. Spangler. Indoor Air Pollution: A Health Perspective.

Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

Soviero, M. M. “Can Your House Make You Sick?” Popular Science (July

1992): 80.

Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is one of the nation’s foremost

conserva-

tion

organizations and has worked for over 100 years to

preserve “the wild places of the earth.” Founded in 1892 by

author and

wilderness

explorer

John Muir

, who helped

lead the fight to establish

Yosemite National Park

, the

group’s first goal was to preserve the Sierra Nevada mountain

chain. Since then, the club has worked to protect dozens of

other national treasures.

The preserve of Mount Rainier was one of the Sierra

Club’s earliest achievements, and in 1899 Congress made

that area into a

national park

. The group also helped to

establish Glacier National Park in 1910. The Sierra Club

supported the creation of the

National Park Service

in

1916, and in 1919 began a campaign to halt the indiscrimi-

nate cutting of redwood trees.

The club has helped secure many conservation victo-

ries. They worked to create such national parks as Kings

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Silt

Canyon, Olympic, and Redwood, national seashores such

as Point Reyes in California and Padre Island in Texas, as

well as the Jackson Hole National Monument. The club

also campaigned to expand Sequoia and Grand Teton na-

tional parks. In the 1960s, the Sierra Club helped to secure

such legislative victories as the

Wilderness Act

in 1964,

the establishment of the National Wilderness Preservation

System, and the expansion of the Land and

Water Conser-

vation

Fund in 1968.

By 1970, the Sierra Club had 100,000 members, with

chapters in every state, and the group took advantage of

growing public support for the

environment

to accelerate

progress towards conserving America’s natural heritage. The

National Environmental Policy Act

was passed by Con-

gress that year, and the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) was created. Later, the club helped defeat a proposal

to build a fleet of polluting Supersonic Transports, and they

organized the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund. In 1976,

the club’s lobbying efforts sped passage of the

Bureau of

Land Management

(BLM) Organic Act, which increased

governmental protection for an additional 459 million acres

(185 ha).

One of the most important victories for the Sierra

Club came in 1980, when a year-long campaign culminated

in passage of the Alaska National Interest Conservation Act,

establishing 103 million acres (41.6 million ha) as either

national parks, monuments, refuges, or wilderness areas.

Superfund legislation was also enacted to clean up the na-

tion’s abandoned toxic waste sites.

The decade of the 1980s, however, was a difficult

one for conservationists. With James Watt as Secretary of

Interior under President Ronald Reagan, and Ann Gorsuch

Burford as EPA administrator, the Sierra Club was placed

in a defensive position. The group focused mainly on pre-

venting environmentally destructive projects and legisla-

tion—for example, blocking the MX missile complex in the

Great Basin (1981), preventing weakening of the

Clean Air

Act

, and stopping BLM from dropping 1.5 million acres

(607,030 ha) from its wilderness inventory in 1983. Despite

government interference, pressure from the public and from

Congress helped the club continue its record of positive

accomplishments, including the designation of 6.8 million

acres (2.7 million ha) of wilderness in 18 states (1984),

new wilderness designations in Alabama, Oklahoma, and

Washington, and the addition of 40 rivers to the National

Wild and Scenic River System.

In 1990, after years of grassroots lobbying, a compro-

mise Clean Air Act was reauthorized, strengthening safe-

guards against

acid rain

and

air pollution

. Current projects

include protecting the last remaining ancient forests of the

Pacific Northwest; preventing oil and gas drilling in the 1.5-

million-acre (607,030-ha) Arctic

National Wildlife Refuge

1292

in Alaska; securing wilderness and park areas in California,

Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina,

South Dakota, New Mexico, and Utah; and combating

global warming and the depletion of the world’s protective

ozone

layer.

In 2001, the Sierra Club began its hundred and tenth

year of work to protect the environment. By 2002, it had

grown to 700,000 members and had 58 chapters across the

United States, with an annual budget of $38 million. Having

become so large and influential, the Sierra Club is now

considered one of the “big ten” American conservation orga-

nizations. An extensive professional staff is required to oper-

ate this complex organization, and members tend to have

little influence over club policy at the national level. Some

radical activists have criticized mainline organizations of this

kind for being too conservative, too comfortable in their

relationship to established powers, and too willing to com-

promise basic principles in order to maintain power and

prestige. Supporters of the club argue that a spectrum of

environmental organizations is desirable and that different

organizations can play useful roles.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Sierra Club, 85 Second St., Second Floor, San Francisco, CA USA

94105-3441 (415) 977-5500, Fax: (415) 977-5799, Email:

information@sierraclub.org, <http://www.sierraclub.org>

Silent Spring

see

Carson, Rachel

Silt

A

soil

separate consisting of particles of a certain equivalent

diameter. The most commonly used size for silt is from 0.05

to 0.002 mm equivalent diameter. This is the size used by the

Soil Science Society of America and the

U.S. Department of

Agriculture

, but others recognize slightly different equiva-

lent diameters. As compared to clay (less than 0.002 mm),

the silt fraction is less reactive and has a low cation exchange

capacity. Because of its size, which is intermediate between

clay and sand, silt contributes to formation of desirable pore

sizes, and the

weathering

of silt minerals provides available

plant nutrients. Wind-blown silt deposits are referred to

as “loess.” See also Soil conservation; Soil consistency; Soil

profile

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Peter Alfred David Singer

Siltation

The process or action of depositing

sediment

. Sediment is

composed of solid material, mineral or organic, and can be

of any texture. The material has been moved from its site

of origin by the forces of air, water, gravity, or ice and has

come to rest on the earth’s surface. The term siltation does

not imply the deposition of

silt

separates, although the sedi-

ment deposited from

erosion

of agricultural land is often

high in silt because of the sorting action into

soil

separates

during the erosion process.

Silver Bay

Silver Bay, on the Minnesota shore of Lake Superior, be-

came the center of

pollution control

lawsuits in the 1970s

when cancer-causing asbestos-type fibers, released into the

lake by a Silver Bay factory, turned up in the drinking water

of numerous Lake Superior cities. While

pollution

lawsuits

have become common, Silver Bay was a landmark case in

which a polluter was held liable for probable, but not proven,

environmental health

risks.

Asbestos

, a fibrous silicate

mineral that occurs naturally in rock formations across the

United States and Canada, entered Lake Superior in the

waste material produced by Silver Bay’s

Reserve Mining

Corporation

. This company processed taconite, a low-grade

form of iron ore, for shipment across the

Great Lakes

to

steel-producing regions. Fibrous asbestos crystals removed

from the purified ore composed a portion of the plant’s waste

tailings

. These tailings were disposed of in the lake, an

inexpensive and expedient disposal method. For almost 25

years the processing plant discharged wastes at a rate of

67,000 tons per day into the lake.

Generally clean, Lake Superior provides drinking

water to most of its shoreline communities. However, water

samples from Duluth, Minnesota, 50 mi (80.5 km) south-

west of Silver Bay, showed trace amounts of asbestos-like

fibers as early as 1939. While the term “asbestos” properly

signifies a specific long, thin crystal shape that appears in

many mineral types, both the long fibers and shorter ones,

known as “asbestos-like” or “asbestiform,” have been linked

to

cancer

in humans.

Early incidences of asbestos-like fibers in drinking

water probably resulted from nearby mining activities, but

fiber concentrations suddenly increased in the late 1950s

when Reserve Mining began its tailing

discharge

into the

lake. By 1965 asbestiform fiber concentrations had climbed

significantly, and municipal water samples in the 1970s were

showing twice the acceptable levels defined by the federal

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

(OSHA). Lawsuits filed against Reserve Mining charged

1293

that the company’s activity endangered the lives of the re-

gion’s residents.

Although industrial discharge often endangers com-

munities, the Silver Bay case was a pivotal one because it

was an early test of scientific uncertainty in cases of legal

responsibility. Cancer that results from exposure to asbestos

fibers appears decades after exposure, and in a large popula-

tion an individual’s

probability

of death may be relatively

small. Asbestos concentrations in Lake Superior water also

varied, depending largely upon weather patterns and city

filtration

systems. Finally, it was not entirely proven that

the particular type of fibers released by Reserve Mining were

as carcinogenic as similar fibers found elsewhere. In such

circumstances it is difficult to place clear blame on the agency

producing the pollutants. The 200,000 people living along

the lake’s western arm were clearly at some risk, but the

question of how much risk must be proven to close company

operations was difficult to answer. Furthermore, the Reserve

plant employed nearly all the breadwinners from nearby

towns. Plant closure essentially spelled death for Silver Bay.

In 1980 a federal judge ordered the plant closed until

an on-land disposal site could be built. Reserve Mining did

construct on-shore tailings ponds, which served the company

for several years until economic losses finally closed the plant

in the late 1980s.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Carter, L. J. “Pollution and Public Health: Taconite Case Poses Major

Test.” Science 186 (October 4, 1974): 31–6.

Sigurdson, E. E. “Observations of Cancer Incidence Surveillance in Duluth,

Minnesota.” Environmental Health Perspectives 53 (1983): 61–7.

Peter Alfred David Singer (1946 – )

Australian philosopher and animal rights activist

Philosopher and leading advocate of the animal liberation

movement, Singer was born in Melbourne,

Australia

. While

teaching at Oxford University in England, Singer encoun-

tered a group of people who were vegetarians not because

of any personal distaste for meat, but because they felt, as

Singer later wrote, that “there was no way in which [mal-

treatment of animals by humans] could be justified ethically.”

Impressed by their argument, Singer soon joined their ranks.

Out of his growing concern for the rights of animals came

the book Animal Liberation, a study of the suffering we inflict

upon animals in the name of scientific experimentation and

food production. Animal Liberation caused a sensation when

it was published in 1972 and soon became a major manifesto

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sinkholes

of the growing animal liberation movement in North

America, Australia, England, and elsewhere.

As a utilitarian, Singer—like his nineteenth-century

forebear and founder of

utilitarianism

, the English philoso-

pher Jeremy Bentham—believes that morality requires that

the total amount of happiness be maximized and pain mini-

mized. Or, as the point is sometimes put, we are morally

obligated to perform actions and promote policies and prac-

tices that produce “the greatest happiness of the greatest

number.” But, Singer says, the creatures to be counted within

this number should include all sentient creatures, animals

as well as humans.

To promote only the happiness of humans and to

disregard the pains of animals Singer calls speciesism—the

view that one

species

, Homo sapiens, is privileged above all

others. Singer likens

speciesism

to sexism and racism. The

idea that one sex or race is innately superior to another

has been discredited. The next step, Singer believes, is to

recognize that all sentient creatures—human and nonhuman

alike—deserve moral recognition and respect. Just as we do

not eat the flesh or use the skin of our fellow humans, so,

Singer argues, should we not eat meat or wear fur from

animals. Nor is it morally permissible for humans to kill

animals, to confine them, or to subject them to lethal labora-

tory experiments.

Although Singer’s conclusions are congruent with

those of

Tom Regan

and other defenders of

animal rights

,

the route by which he reaches them is quite different. As a

utilitarian, Singer emphasizes sentience, or the ability to

experience pleasure and pain. Regan, by contrast, emphasizes

the

intrinsic value

or inherent moral worth of all living

creatures. Despite their differences, both have come under

attack from the fur industry, defenders of “factory farming,”

and advocates of animal experimentation. Singer remains a

key figure at the center of this continuing storm.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ball, T., and R. Dagger. “Liberation Ideologies.” In Political Ideologies and

the Democratic Ideal. New York: Harper-Collins, 1991.

Singer, Peter. A Darwinian Left: Politics, Evolution, and Cooperation. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

———. Animal Liberation. 2nd ed. New York: Random House, 1990.

———. Ethics into Action: Henry Spim and the Animal Rights Movement.

Latham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998.

———. Practical Ethics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

———. Writings on an Ethical Life. New York: Ecco Press, 2000.

———, and Helga Kuhse, eds. Bioethics: An Anthology. Malden, MA:

Blackwell Publishers, 1999.

———, and T. Regan, eds. Animal Rights and Human Obligations. Engle-

wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976.

1294

Sinkholes

Sinkholes are one of the main landforms in karst

topogra-

phy

, so named for the region in Yugoslavia where solution

features such as caves, caverns, disappearing streams and

hummocky terrain predominate. Karst features occur pri-

marily in limestone but may also occur in dolomite, chert,

or even gypsum (Alabaster Caverns in Oklahoma).

As the name implies, sinkholes are depressions formed

by solution enlargement or the

subsidence

of a cavern roof.

Subsidence may occur slowly, as the cavern roof is gradually

weakened by solution, or rapidly as the roof collapses. Several

of the latter occurrences have gained widespread coverage

because of the size and amount of property damage involved.

An often-described sinkhole formed during May 1981

in Winter Park, Florida, swallowing a three-bedroom house,

half a swimming pool, and six Porsches in a dealer’s lot. The

massive “December Giant” occurred near Montevallo, Ala-

bama, and measured 400 ft (122 m) wide by 50 ft (15 m) deep.

A nearby resident reported hearing a roaring noise and break-

ing timbers, as well as feeling earth tremors under his house.

Cenotes is the Spanish name for sinkholes. One sacred

cenote at the Mayan city of Chichen Itza in Yucatan, Mex-

ico, was known as “the Well of Sacrifice.” Archaeologists

postulate that, to appease the gods during a

drought

, human

sacrifices were cast into the water 80 ft (24 m) below, fol-

lowed by a showering of precious possessions from onlookers.

Since most of the gold and silver objects from the New

World were melted down, these sacrifices are now highly

prized artifacts from pre-Columbian civilizations.

Although occurring naturally, sinkhole formation can

be intensified by human activity. These sinkholes offer an

easy pathway for injection of contaminated

runoff

and sew-

age from septic systems into the

groundwater

. Because

karst landscapes have extensive underground channels, the

polluted water often travels considerable distances with little

filtration

or chemical modification from the relatively inert

limestone. Therefore, the most serious hazard posed by sink-

holes is the access they provide for turbid, polluted surface

waters. This allows bacteria to thrive, so testing of spring

water that emerges within or below karst regions is vital.

Sinkholes also pose special problems for construction

of highways, reservoirs, and other massive objects. Fluctuat-

ing water levels weaken the overlying rock when the

water

table

is high, but remove support when water levels are low.

Thornbury (1954) described the problems resulting from

efforts by Bloomington, Indiana, to build a water supply

reservoir

on top of karst topography. Much valuable water

escaped through channels in the limestone beneath the dam.

This structure eventually was abandoned and a new reservoir

constructed in a region composed of relatively impervious

siltstone below the limestone.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Slash and burn agriculture

Anthropogenic

(human-caused) sinkholes form as a

result of mine subsidence, often catastrophically. Collapsing

mine tunnels within the 1,000-mi (1,600-km) labyrinth in

the historic Tri-State Mines of Kansas, Missouri, and Okla-

homa have created scenarios very similar to the Winter Park,

Florida, example. Subsidence of the strata overlying under-

ground

coal

mines is another rich source of these anthropo-

genic sinkholes.

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Coates, D. R., ed. Environmental Geomorphology. Binghampton, NY: State

University of New York, 1971.

Keller, E. A. Environmental Geology. 4th ed. Columbus, OH: Charles E.

Merrill Publishing Co., 1985.

Thornbury, W. D. Principles of Geomorphology. New York: John Wiley &

Sons, 1954.

P

ERIODICALS

“Into the Well of Sacrifice,” National Geographic Magazine (October 1961):

540–561.

Site index

A means of evaluating a forest’s potential to produce trees

for timber. Site refers to a defined area, including all of

its environmental features, that supports or is capable of

supporting a stand of trees. Site index is an indicator used

to predict timber yield based on the height of dominant and

co-dominant trees in a stand at a given index age, usually

50 or 100 years. Normally, site index curves are prepared by

graphically plotting projected tree height as a function of

age. See also Forest management

Site remediation

see

Hazardous waste site remediation

Skidding

A technique in forest harvesting by which logs or whole

trees are dragged over the ground, as opposed to being lifted

in the air, to a landing, where they are loaded on trucks for

transport to a mill. The logs may be dragged by mechanical

means, such as a crawler tractor or rubber-tired skidder, or

by draft animals. Skidding normally disturbs the ground

surface and forms “skid trails” which may be used once or

reused in subsequent harvests.

Soil

in skid trails, especially

on steep land, may channel water flow during rainfall and

snow melt and be susceptible to

erosion

.

1295

SLAP suits

see

Strategic lawsuits to intimidate public

advocates

Slash

The waste material, consisting of limbs, branches, twigs,

leaves, or needles, left after forest harvesting.

Logging

slash

left on the ground can protect the

soil

from raindrop impacts

and

erosion

, and it can decompose to make

humus

and

recycle nutrients. Unusually large amounts of slash, which

may present a fire hazard or provide favorable

habitat

for

harmful insects or disease organisms, usually must be reduced

by burning or mechanical chopping.

Slash and burn agriculture

Also known as swidden cultivation or

shifting cultivation

,

slash-and-burn agriculture is a primitive agricultural system

in which sections of forest are repeatedly cleared, cultivated,

and allowed to regenerate over a period of many years. This

kind of cultivation was used in Europe during the Neolithic

period, and it is still widely used by

indigenous peoples

and

landless peasants in the tropical rain forests of South America.

The plots used in slash-and-burn agriculture are small,

typically 1–1.5 acres (0.4–0.6 hectare). They are also poly-

cultural and polyvarietal; farmers plant more than one crop

on them at a time, and each of these crops may be grown

in several varieties. This helps control populations of agricul-

tural pests. The cutting and burning involved in clearing the

site releases nutrients which the cultivated crops can utilize,

and the fallow period, which usually lasts at least as long

as 15 years, allows these nutrients to accumulate again. In

addition to restoring fertility, re-growth protects the

soil

from

erosion

.

Families and other small groups practicing slash-and-

burn agriculture generally clear one or two new plots a year,

working a number of areas at various stages of cultivation

at a time. These plots can be close to each other, even

interconnected, or spread out at a distance through the forest,

designed to take advantage of particularly fertile soils or to

meet different needs of the group. As the nutrients are

exhausted and productivity declines, the areas cleared for

slash-and-burn agriculture are rarely simply abandoned; the

fallow period begins gradually, and

species

such as fruit

trees are still cultivated as the forest begins to reclaim the

open spaces. The forest may contain originally cultivated

species that still yield a harvest many years after the plot has

been overgrown.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sludge

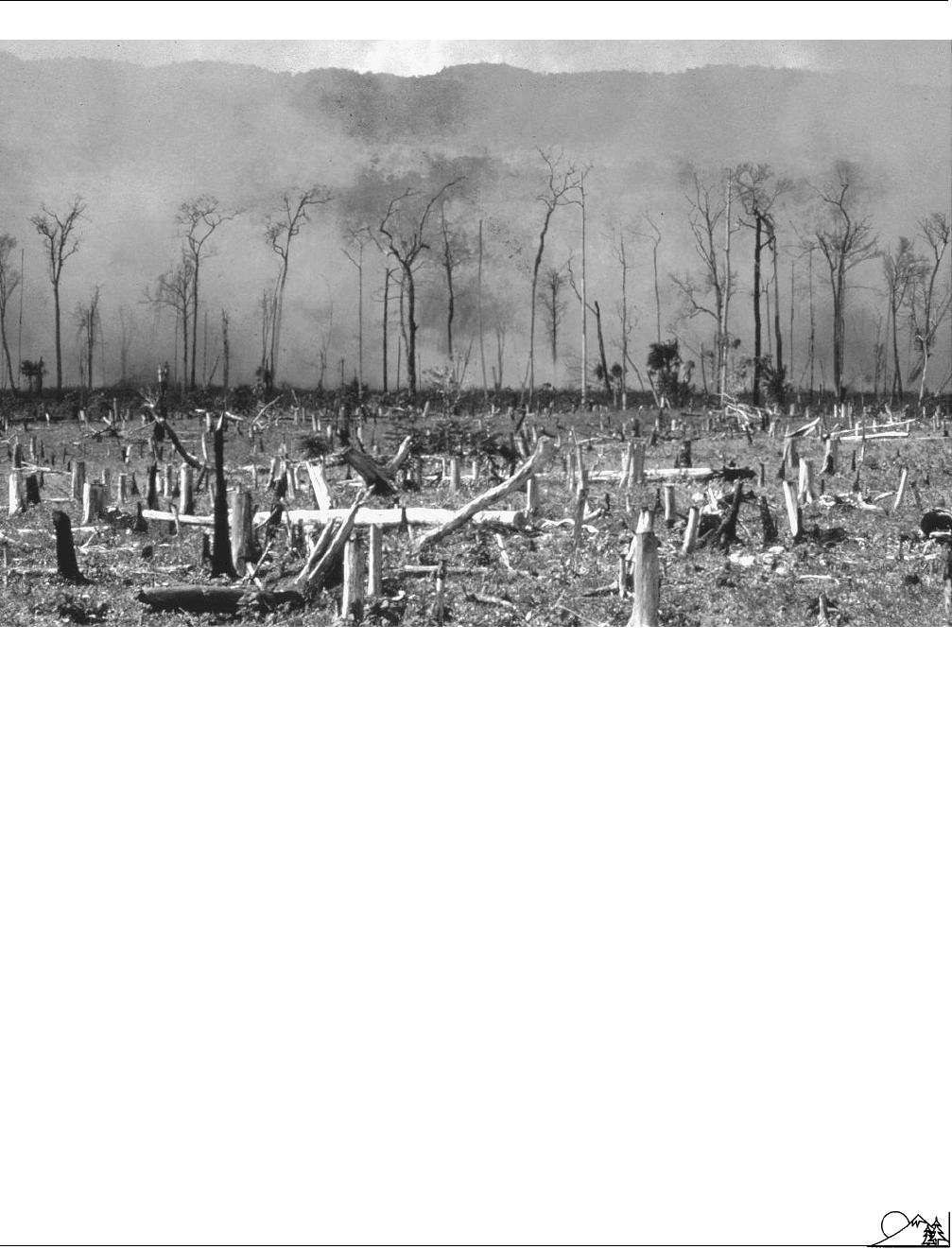

Jungle in Guatemala is burned to clear land for raising corn and cattle. (Photograph by George Holton. Photo Researchers

Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

Although this system of agriculture was practiced for

thousands of years with relatively modest effects on the

environment

, the pressures of a rapidly growing population

in South America have made it considerably less benign.

Population growth

has greatly increased the number of

peasants who do not own their own land; they have been

forced to migrate into the rain forests, where they subsist

practicing slash-and-burn agriculture. In Brazil, the number

of farmers employing this system of agriculture has increased

by more than 15% a year since 1975. A recently released

report by the United Nations Population Fund has empha-

sized the destruction this system can cause when practiced

on such a large scale and identified it as a threat to species

diversity. See also Agricultural revolution; Agricultural tech-

nology; Agroecology

[Douglas Smith]

Sludge

A suspension of solids in liquid, usually in the form of a liquid

or a

slurry

. It is the residue that results from

wastewater

1296

treatment operations, and typical concentrations range from

0.25 to 12% solids by weight. An estimated 8.5 million dry

tons of municipal sludge is produced in the United States

each year.

The volume of sludge produced is small compared

with the volume of wastewater treated. The cost of sludge

treatment, however, is estimated to be from 25 to 40% of

the total cost of operating a wastewater-treatment plant. In

the design of

sludge treatment and disposal

facilities,

the term sludge refers to primary, biological, and chemical

sludges, and excludes grit and screenings. Primary sludge

results from primary

sedimentation

, while the sources of

biological and chemical sludges are secondary biological and

chemical settling and the processes used for thickening, di-

gesting, conditioning, and dewatering the sludge from the

primary and secondary settling operations.

Primary sludge is usually gray to dark gray in color

and has a strong offensive odor. Fresh biological sludge—

activated sludge, for example—is brownish and has a musty

or earthy odor. Chemical sludge can vary in color depending

on composition and may have objectionable odor. There are