Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Soil profile

P

ERIODICALS

Helms, D. “Conserving the Plains: The Soil Conservation Service in the

Great Plains.” Agricultural History 64 (Spring 1990): 58–73+.

Soil consistency

The manifestations of the forces of cohesion and adhesion

acting within the

soil

at various water contents, as expressed

by the relative ease with which a soil can be deformed or

ruptured. Consistency states are described by terms such as

friable, soft, hard, or very hard. These states are assessed

by thumb and thumbnail penetrability and indentability, or

more quantitatively, by Atterberg limits, which consist of

liquid limit, plastic limit, and plasticity number. Atterberg

limits are usually determined in the laboratory and are ex-

pressed numerically. See also Soil compaction; Soil conserva-

tion; Soil texture

Soil, contaminated

see

Contaminated soil

Soil eluviation

When water moves through the

soil

, it also moves small

colloidal-sized materials. This movement or

leaching

of

materials like clay, iron, or calcium carbonate is called eluvia-

tion. The area where the materials have been removed is

the zone of eluviation and is called the E

horizon

. Zones

of eluviation contain fewer nutrients for plant growth. E

horizons are often found in forested soils.

Soil illuviation

When water moves through the

soil

, it moves small colloi-

dal-sized particles with it. These particles of clay, iron,

hu-

mus

, and calcium carbonate will be deposited in zones below

the surface or in the

subsoil

. The zones are called illuvial

zones and the process is referred to as illuviation. Illuvial

zones are most often referred to as B horizons, and the

subscript with the B designates the kind of material translo-

cated (i.e., B

t

= clay accumulation).

Soil liner

One of the requirements of modern sanitary landfills is that

a

soil

liner be placed on top of the existing soil. Liners are

needed to prevent the penetration of

landfill

leachate into

the soil. Without a liner, leachate could move through the

1317

soil and contaminate the

groundwater

. Soil liners can be

made of clay, plastic,

rubber

, blacktop, or concrete.

Soil loss tolerance

Soil

loss tolerance is the maximum average annual soil re-

moval by

erosion

that will allow continuous cropping and

maintain soil productivity (T). It is occasionally defined as

the maximum amount of soil erosion offset by the maximum

amount of soil development while maintaining an equilib-

rium between soil losses and gains. T is usually expressed

in terms of tons per acre or tons per hectare. Because T

values are difficult to quantify, they are usually inferred by

human judgment rather than scientific analysis. In determin-

ing T values, the depth of the soil to consolidated material

or depth to an unfavorable

subsoil

is considered. T values

are an expression of concern for plant growth but may not

adequately reflect environmental concerns.

Soil organic matter

Additions of plant debris to soils will initiate the build up

of organisms that will decompose the plant debris. After

decomposition

the organic material will be called organic

matter or

soil humus

. This decomposed plant debris will

be in the form of very small particles and will coat the sand,

silt

, and clay particles making up the mineral soil particles,

thus making the soil black. The more organic matter accu-

mulating in a soil, the darker the soil will become. Continued

additions of organic matter are important to create a soft,

tillable soil that is conducive to plant growth. Organic matter

is important in soils because it will add nutrients, store

nitrogen

and other positive cations, and create a stronger

soil aggregate that will withstand the impact of raindrops

and thus prevent water

erosion

.

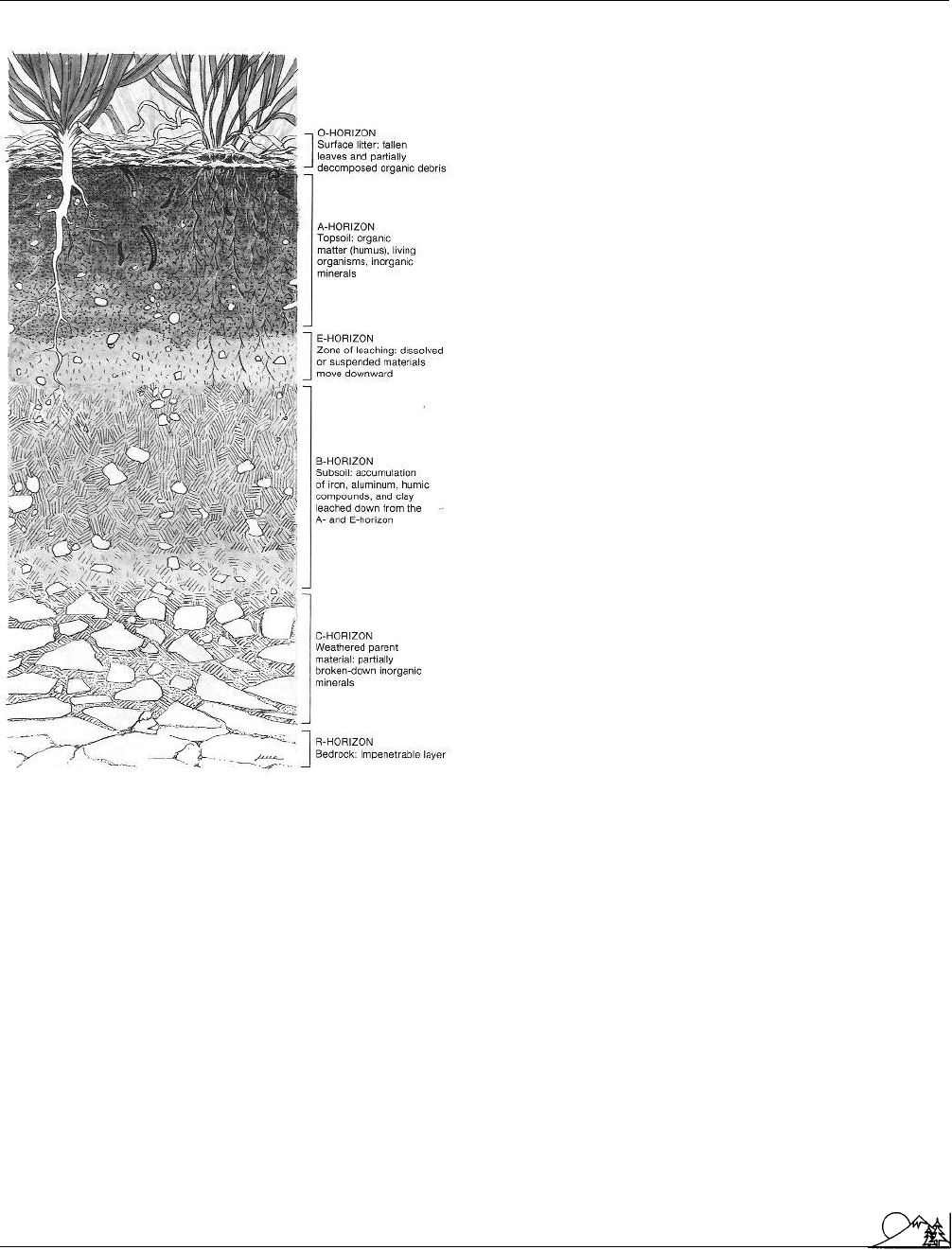

Soil profile

The layers in the

soil

from the surface to the

subsoil

. The

soil profile is the collection of soil

horizons

. Soil profiles

will vary from location to location because of the five soil-

forming factors:

climate

, vegetation,

topography

, soil par-

ent material, and the length of time the soil has been

weath-

ering

. By looking at a soil’s profile many interpretations can

be made about

land use

and the suitability of the soil for

a specific use.

Soil, saline

see

Saline soil

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Soil survey

A soil profile showing the horizons in a cross-

section of soil. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

Soil survey

A

soil

survey is a combination of field and laboratory activi-

ties intended to identify the basic physical and chemical

properties of soils, establish the distribution of those soils

at specific map scales, and interpret the information for a

variety of uses.

There are two kinds of soil surveys, general purpose

and specific use. General purpose surveys collect and

display data on a wide range of soil properties which can

be used to evaluate the suitability of the soil or area for

a variety of purposes. Specific use soil surveys evaluate

the suitability of the land for one specific use. Only

1318

physical and chemical data related to that particular use

are collected, and map units are designed to convey that

specific suitability.

A soil survey consists of three major activities: research,

mapping, and interpretation. The research phase involves

investigations that relate to the distribution and performance

of soil; during the mapping phase, the land is actually walked

and the soil distribution is noted on a map base which is

reproducible. Interpretation involves the evaluation of the

soil distribution and performance data to provide assess-

ments of soil suitability for different kinds of

land use

.

During the research phase of the survey, soil scientists

first establish which soil properties are important for that

type of survey. They then establish field relationships be-

tween soil properties and landscape features and determine

the types of soils to be mapped, preparing a map legend.

In this phase, scientists also evaluate land productivity and

recommend management practices as they relate to the map-

ping units proposed in the map legend.

Mapping is perhaps the most widely recognized phase

of a soil survey. It is conducted by evaluating and delineating

the soils in the field at a specified map intensity or scale.

Soil profile

observations are made at three levels of detail.

Representative profiles are taken from soil pits, generally

with laboratory corroboration of the observations made by

soil scientists. Intermediate profiles are taken from soil pits,

roadside excavations, pipelines or other chance exposures,

and some sampling and description does occur at this level.

Soil-type identifications are taken from auger holes or small

pits, and only brief descriptions are made without laboratory

confirmation.

With information gathered from sampling, as well

as from the earlier research phase, soil scientists draw soil

boundaries on an aerial photograph. These delineations or

map units are systematically checked by field transects—

straight-line traverses across the landscape with samples

taken at specified intervals to confirm the map-unit compo-

sition.

Field research and the process of mapping produce a

range of information that requires interpretation. Interpreta-

tions can include discussions of land use potential, manage-

ment practices, avoidance of hazards, and economic evalua-

tions of soil data. The interpretation of the information

gained during a soil survey is based on crop yield estimates

and soil response to specific management. Crop yields are

estimated in the following ways: by comparison with data

from experimental sites on identified soil types; by field

experiments conducted within the survey area; from farm

records, demonstration plots or other farm system studies;

and by comparison of known crop requirements with the

physical and chemical properties of soils. Soil response in-

volves the evaluation of how the soils will respond to changes

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solar constant cycle

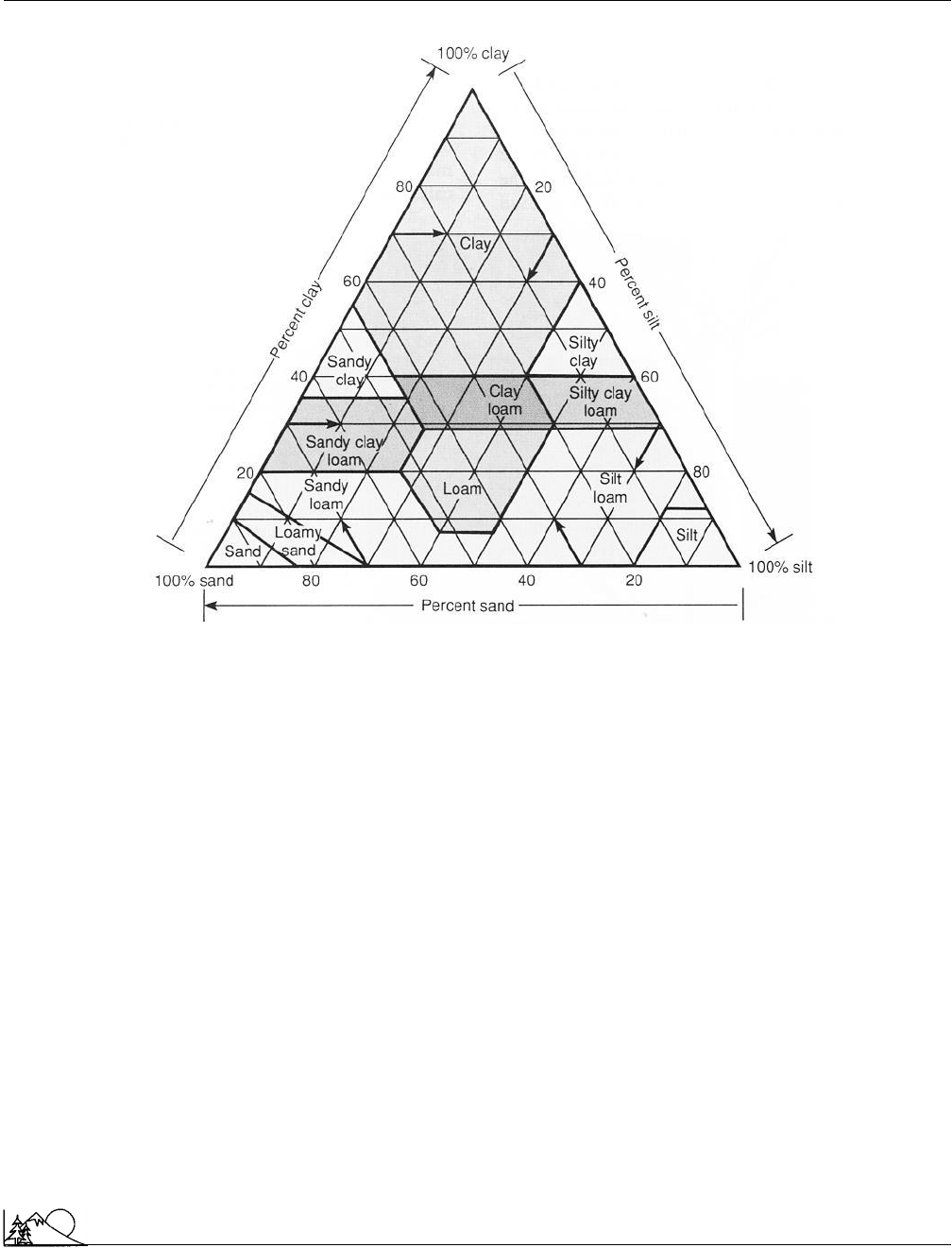

Soil texture depends on the relative proportions of sand, silt and clay in a soil, as represented in this diagram.

(McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

in use or management, such as

irrigation

,

drainage

, and

land

reclamation

. Part of this evaluation includes an assess-

ment of hazards that may result from changes such as

ero-

sion

or

salinization

.

In general purpose surveys, which are the kind

conducted in the United States, soils are mapped according

to their properties on the hypothesis that soils which look

and feel alike will behave the same, while those that do

not will respond differently. A soil survey attempts to

delineate areas that behave differently or will respond

differently to some specified management, and the mapping

units provide the basis for locating and predicting these

differences. See also Contaminated soil; Soil conservation;

Soil Conservation Service; Soil texture; U. S. Department

of Agriculture

[James L. Anderson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dent, D., and A. Young. Soil Survey and Land Evaluation. Boston: Allen

and Unwin, 1981.

1319

Soil texture

The relative proportion of the mineral particles that make

up a

soil

or the percent of sand,

silt

, and clay found in a

soil. Texture is an important soil characteristic because it

influences water

infiltration

, water storage, amount of

aera-

tion

, ease of tilling the soil, ability to withstand a load, and

soil fertility. Textural names are given to soil based on the

percentage of sand, silt, and clay. For example, loam is a

soil with equal proportions of sand, silt, and clay. It is best

for growing most crops.

Solar cell

see

Photovoltaic cell

Solar constant cycle

The solar constant is a measure of the amount of radiant

energy reaching the earth’s outer

atmosphere

from the sun.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solar detoxification

More precisely, it is equal to the rate at which solar radiation

falls on a unit area of a plane surface at the top of the

atmosphere and oriented at a perpendicular distance of 9.277

x10

7

mi (1.496 X 10

8

km) from the sun. That distance is

the average (mean) distance between earth and sun during

the course of a single year.

Measuring the solar constant has historically been a

difficult challenge since there were few good methods for

measuring energy levels at the top of the atmosphere. A

solution to this problem was made possible in 1980 with

the launching of the Solar Maximum (Solar Max) Mission

spacecraft. After repair by the Challenger astronauts in 1984,

Solar Max remained in orbit, taking measurements of solar

phenomena until 1989. As a result of the data provided by

Solar Max, the solar constant has now been determined to

be 1.96 calories per 0.3 in

2

(2 cm

2

) per minute, or 1,367

watts per 3.3 ft (1 m). This result confirms the value of 2.0

calories per cm

2

per minute long used by scientists.

In addition to obtaining a good value for the solar

constant, however, Solar Max made another interesting dis-

covery. The solar constant is not, after all, really constant.

It varies on a daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly basis, and

probably much longer. The variations in the solar constant

are not large, averaging at a few tenths of a percent.

Scientists have determined the cause of some variabil-

ity in the solar constant and are hypothesizing others. For

example, the presence of sunspots results in a decrease in

the solar constant of a few tenths of a percent. Sunspots are

regions on the sun’s surface where temperatures are signifi-

cantly lower than surrounding areas. Since the sun presents

a somewhat cooler face to the earth when sunspots are pres-

ent, a decrease in the solar constant is not surprising.

Other surface features on the sun also affect the solar

constant. Solar flares, for example, are outbursts or explo-

sions of energy on the surface that may last for many weeks.

Correlations have been made between the presence of solar

flares and the solar constant over the twenty-seven-day pe-

riod of the sun’s rotation.

A longer-lasting effect is caused by the eleven-year

sunspot cycle. As the number of sunspots increase during

the cycle, so does the solar constant. For some unknown

reason, this long-term effect is just the opposite of that

observed for single sunspots.

Scientists believe that historical studies of the solar

constant may provide some clues about changes in the earth’s

climate

. The nineteenth-century British astronomer E.

Walter Maunder pointed out that sunspots were essentially

absent during the period of 1645 to 1715, a period now called

the Maunder minimum. The earth’s climate experienced a

dramatic change at about the same time, with temperatures

dropping to record lows. These changes are now known as

the Little

Ice Age

. It seems possible that further study of

1320

the solar constant cycle may explain the connection between

these two phenomena.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Chorlton, Windsor, and the editors of Time-Life Books. Ice Ages. Alexan-

dria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983.

Hudson, Hugh S. “Solar Constant.” In McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Sci-

ence & Technology. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992.

Solar detoxification

Solar energy

is being investigated as a potential means to

destroy environmental contaminants. In solar

detoxifica-

tion

, photons in sunlight are used to break down contami-

nants into harmless or more easily treatable products. Solar

detoxification is a “destructive” technology—it destroys con-

taminants as opposed to “transfer-of-phase” technologies

such as activated

carbon

or air stripping, which are more

commonly used to remove contaminants from the

envi-

ronment

.

In a typical photocatalytic process, water or

soil

con-

taining organic contaminants is exposed to sunlight in the

presence of a catalyst such as titanium dioxide or humic and

fulvic acids. The catalyst absorbs the high energy photons,

and oxygen collects on the catalyst surface, resulting in the

formation of reactive

chemicals

referred to as hydroxyl free-

radicals and atomic oxygen (singlet oxygen). These reactive

chemicals transform the organic contaminants into degrada-

tion products, such as

carbon dioxide

and water. Solar

detoxification can be accomplished using natural sunlight or

by using inside solar simulators or outside solar concentra-

tors, both of which can concentrate light 20 times or more.

The effectiveness of solar detoxification in both water and

soil is affected by

sorption

of the toxic compounds on sedi-

ments or soil and the depth of light penetration. Solar detoxi-

fication of volatilized toxic compounds may also occur natu-

rally in the

atmosphere

.

For solar detoxification to be successfully accom-

plished, toxic chemicals should be converted to thermody-

namically stable, non-toxic end products. For example, chlo-

rinated compounds should be transformed to carbon dioxide,

water, and hydrochloric

acid

through the general sequence:

organic pollutants → aldehydes → carboxylic acids →

carbon dioxide

Photocatalytic degradation such as this usually results

in complete mineralization only after prolonged irradiation.

If intermediates formed in the degradation pathway are non-

toxic, however, the reaction does not have to be driven

completely to carbon dioxide and water for acceptable detox-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solar energy

ification to have occurred. In the solar detoxification of

pentachlorophenol

(PCP) and 2,4-dichlorophenol, for ex-

ample, toxic intermediates were detected; however, with ex-

tended exposure to sunlight, the compounds were rendered

completely nontoxic, as measured by

respiration

rate mea-

surements in

activated sludge

.

Many applications of solar detoxification implemented

at ambient temperatures have only 90–99% efficiency and

do not completely mineralize the compounds. The rate of

some photolytic reactions can be increased by raising the

temperature of the reaction system, but the production of

stable reaction intermediates (some of which may be toxic)

is reduced. The changes in reaction rate have been attributed

to a combination of a thermally induced increase in the

photon-absorption rate, an increase in the quantum yield of

the primary photoreaction, and the initiation of photoin-

duced radical-chain reactions.

Research conducted at the Solar Energy Research In-

stitute (SERI), a laboratory funded by the

U.S. Department

of Energy

, has demonstrated that

chlorinated hydrocar-

bons

, such as trichloroethylene (TCE), trichloroethane

(TCA), and

vinyl chloride

, are vulnerable to photocatalytic

treatment. Other toxic chemicals shown to be degraded by

solar detoxification include a textile dye (Direct Red No.

79), pinkwater, a munitions production waste, and many

types of pesticides, including chlorinated cyclodiene insecti-

cides, triazines, ureas, and dinitroaniline herbicides. In con-

junction with

ozone

and

hydrogen

peroxide, both of which

are strong oxidants, ultraviolet light has been shown to be

effective in oxidizing some refractory chemicals such as

methyl ethyl ketone, a degreaser, and

polychlorinated bi-

phenyls

(PCBs). See also Oxidizing agent

[Judith Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Mill, T., and W. Mabey. “Photodegradation in Water.” In Environmental

Exposure from Chemicals, edited by W. B. Neely and G. E. Blau. CRC

Press, Boca Raton, FL: 1985.

P

ERIODICALS

Al-Ekabi, H., et al. “Advanced Technology for Water Purification by

Heterogenous Photocatalysis.” International Journal of Environment and

Pollution 1, nos. 1–2 (1991): 125–136.

Manilai, V. B., et al. “Photocatalytic Treatment of Toxic Organics in

Wastewater: Toxicity of Photodegradation Products.” Water Research 26,

no. 8 (1992): 1035–1038.

Stephenson, F. A. “Chemical Oxidizers Treat Wastewater.” Environmental

Protection 3, no. 10 (1992): 23–27.

O

THER

Solar Energy Research Institute, Development and Communications Of-

fice. Solar Treatment of Contaminated Water. SERI/SP-220-3517. Goldon,

CO: Solar Heat Research Division, Solar Energy Research Institute, 1989.

1321

Solar energy

The sun is a powerful fusion reactor, where

hydrogen

atoms

fuse to form helium and give off a tremendous amount of

energy. The surface of the sun, also known as the photo-

sphere, has a temperature of 6,000 K (10,000°F [5,538°C]).

The temperature at the core, the region of

nuclear fusion

,

is 36,000,000°F (20,000,000°C). A ball of

coal

the size of

the sun would burn up completely in 3,000 years, yet the

sun has already been burning for three billion years and is

expected to burn for another four billion. The power emitted

by the sun is 3.9 x 10

26

watts.

Only a very small fraction of the sun’s radiant energy,

or insolation, reaches the earth’s

atmosphere

, and only

about half of that reaches the surface of the earth. The other

half is either reflected back into space by clouds and ice or

is absorbed or scattered by molecules within the atmosphere.

The sun’s energy travels 93,000,000 mi (149,667,000 km)

to reach the earth’s surface. It arrives about 8.5 minutes after

leaving the photosphere in various forms of radiant energy

with different wave lengths, known as the electromagnetic

spectrum.

Solar radiation, also known as solar flux, is measured

in Langleys per minute. One Langley equals one calorie

of radiant energy per square centimeter. It is possible to

appreciate the magnitude of the energy produced by the sun

by comparing it to the total energy produced on earth each

year by all sources. The annual energy output of the entire

world is equivalent to the amount the sun produces in about

five billionths of a second. Solar radiation over the United

States each year is equal to 500 times its energy consumption.

The solar energy that reaches the surface of the earth

and enters the biological cycle through

photosynthesis

is

responsible for all forms of life, as well as all deposits of

fossil fuel. All energy on earth comes from the sun, and it

can be utilized directly or indirectly. Direct uses include

passive solar systems such as greenhouses and atriums, as

well as windmills, hydropower, and the burning of

biomass

.

Indirect uses of solar energy include photovoltaic cells, in

which semiconductor crystals convert sunlight into electrical

power, and a process that produces methyl alcohol from

plants.

Wind results from the uneven heating of the earth’s

atmosphere. About 2% of the solar energy which reaches

the earth is used to move air masses, and at any one time

the kinetic energy in the wind is equivalent to 20 times the

current electricity use. Due to mechanical losses and other

factors, windmills cannot extract all this power. The power

produced by a windmill depends on the speed of the wind

and the effective surface areas of the blades, and the maxi-

mum extractable power is about 60%.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solar energy

A solar furnace in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

(Photograph by Mark Antman. Phototake. Reproduced by

permission.)

The use of the water wheel preceded windmills, and

it may be the most ancient technology for utilizing solar

energy. The sun causes water to evaporate, clouds form

upon cooling, and the subsequent precipitation can be stored

behind

dams

. This water is of high potential energy, and

1322

it is used to run water wheels or turbines. Modern turbines

that run electric generators are approximately 90% efficient,

and in 1998 hydroelectric energy produced about 4% of the

primary energy used in the United States.

A passive solar heating system absorbs the radiation

of the sun directly, without moving parts such as pumps.

This kind of low-temperature heat is used for space heating.

Solar radiation may be collected by the use of south-facing

windows in the Northern Hemisphere. Glass is transparent

to visible light, allowing long-wave visible rays to enter, and

it hinders the escape of long-wave heat, therefore raising

the temperature of a building or a greenhouse.

A thermal mass such as rocks, brine, or a concrete floor

stores the collected solar energy as heat and then releases it

slowly when the surrounding temperature drops. In addition

to collecting and storing solar energy as heat, passive systems

must be designed to reduce both heat loss in cold weather

and heat gain in hot weather. Reductions in heat transfer

can be accomplished by heavy insulation, by the use of double

glazed windows, and by the construction of an earth brim

around the building. In hot summer weather, passive cooling

can be provided by building extended overhangs or by plant-

ing deciduous trees. In dry areas such as in the southwestern

United States or the Mediterranean, solar-driven fans or

evaporative coolers can remove a great deal of interior heat.

Examples of passive solar heating include roof-mounted hot-

water heaters, solarian glass-walled rooms or patios, and

earth-sheltered houses with windows facing south.

A simple and innovative technology in passive systems

is a design based on the fact that at depth of 15 ft (4.6 m)

the temperature of the earth remains at about 55°F (13°C)

all year in a cold northern

climate

and about 67°F (19°C)

in warm a southern climate. By constructing air intake tubes

at depths of 15 ft, the air can be either cooled or heated

to reach the earth’s temperature, proving an efficient air

conditioning system.

Active solar systems differ from passive systems in that

they include machinery, such as pumps or electric fans, which

lowers the net energy yield. The most common type of active

systems are photovoltaic cells, which convert sunlight into

direct current electricity. The thin cells are made from semi-

conductor material, mainly silicon, with small amounts of

gallium arsenide or

cadmium

sulfide added so that the cell

emits electrons when exposed to sunlight. Solar cells are

connected in a series and framed on a rigid background.

These modules are used to charge storage batteries aboard

boats, operate lighthouses, and supply power for emergency

telephones on highways. They are also used in remote areas

not connected to a power supply grid for pumping water

either for cattle or

irrigation

.

Both passive and active solar systems can be installed

without much technical knowledge. Neither produces

air

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solid waste

pollution

, and both have a very low environmental impact.

But a well-designed passive system is cheaper than active

one and does not require as much operative maintenance. See

also Alternative energy sources; Energy and the environment;

Energy policy; Passive solar design

[Douglas Smith]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Balcomb, J. D. Passive Solar Building. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992.

Hedger, J. Solar Energy–The Sleeping Giant: Basics of Solar Energy. Deming:

Akela West Publishers, 1993.

P

ERIODICALS

Brown, L. R., et al. “A World Fit to Live In.” UNESCO Courier (November

1991): 28–31.

Peck, L. “Here Comes the Sun.” Amicus Journal 12 (Spring 1990): 27–32.

Solar Energy Research, Development

and Demonstration Act (1974)

Following the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli war in 1973,

Arab oil-producing states imposed an embargo on oil exports

to the United States. The embargo lasted from October

1973 to March 1974, and the long gas lines it caused high-

lighted the United States’ dependence on foreign

petro-

leum

. Congress responded by enacting the

Solar Energy

Research, Development and Demonstration Act of 1974.

The act stated that it was henceforth the policy of the

federal government to “pursue a vigorous and viable program

of research and resource assessment of solar energy as a

major source of energy for our national needs.” The act’s

scope embraced all energy sources which are renewable by

the sun—including solar thermal energy, photovoltaic en-

ergy, and energy derived from wind, sea thermal gradients,

and

photosynthesis

. To achieve its goals, the act established

two programs: the Solar Energy Coordination and Manage-

ment Project and the Solar Energy Research Institute.

The Solar Energy Coordination and Management

Project consisted of six members, five of whom were drawn

from other federal agencies, including the National Science

Foundation, the Department of Housing and Urban Devel-

opment, the

Federal Power Commission

, NASA, and the

Atomic Energy Commission

. Congress intended that the

project would coordinate national solar energy research, de-

velopment, and demonstration projects, and would survey

resources and technologies available for solar energy produc-

tion. This information was to be placed in a Solar Energy

Information Data Bank and made available to those involved

in solar energy development.

1323

Over the decade following the passage of the act in

1974, the United States government spent $4 billion on

research in solar and other

renewable energy

technologies.

During the same period, the government spent an additional

$2 billion on tax incentives to promote these alternatives.

According to a

U.S. Department of Energy

report issued

in 1985, these efforts displaced petroleum worth an esti-

mated $36 billion.

Despite the promise of solar energy in the 1970s and

the fear of reliance on foreign petroleum, spending on renew-

able energy sources in the United States declined dramati-

cally during the 1980s. Several factors combined during that

decade to weaken the federal government’s commitment to

solar power, including the availability of inexpensive petro-

leum and the skeptical attitudes of the Reagan and Bush

administrations, which were distrustful of government-

sponsored initiatives and concerned about government

spending.

To carry out the research and development initiatives

of the Solar Energy Coordination and Management Project,

the act also established the Solar Energy Research Institute,

located in Golden, Colorado. In 1991, the Solar Energy

Research Institute was renamed the National Renewable

Energy Laboratory and made a part of the national laboratory

system. The laboratory continues to conduct research in the

production of solar energy and energy from other renewable

sources. In addition, the laboratory studies applications of

solar energy. For example, it has worked on a project using

solar energy to detoxify

soil

contaminated with hazardous

wastes.

[L. Carol Ritchie]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

“Federal R&D Funding for Solar Technologies.” Solar Industry Journal

(First Quarter 1992).

“Photovoltaics.” Solar Industry Journal (First Quarter 1992).

O

THER

Solar Energy Research, Development, and Demonstration Act of 1974,

Pub. L. No. 93-473, 88 Stat. 1431 (1974), codified at 42 U.S.C. 5551, et

seq. (1988).

Solid waste

Solid waste is composed of a broad array of materials dis-

carded by households, businesses, industries, and agriculture.

The United States generates more than 11 billion tons (10

billion metric tons) of solid waste each year. The waste is

composed of 7.6 billion tons (6.9 billion metric) of industrial

nonhazardous waste, 2–3 billion tons (1.8–2.7 billion metric)

of oil and gas waste, over 1.4 billion tons (1.3 billion metric)

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solid waste

of mining waste, and 195 million tons (177 billion metric)

of

municipal solid waste

.

Not all solid waste is actually solid. Some semi-solid,

liquid, and gaseous wastes are included in the definition of

solid waste. The

Resource Conservation and Recovery

Act

(RCRA) defines solid waste to include

garbage

, refuse,

sludge

from municipal

sewage treatment

plants, ash from

solid waste incinerators, mining waste, waste from construc-

tion and demolition, and some hazardous wastes. Since the

definition is so broad, it is worth considering what the act

excludes from regulations concerning solid waste: untreated

sewage, industrial

wastewater

regulated by the

Clean

Water Act

,

irrigation

return flows, nuclear materials and

by-products, and hazardous wastes in large quantities.

RCRA defines and establishes regulatory authority for

hazardous waste

and solid waste. According to the act,

some hazardous waste may be disposed of in solid waste

facilities. These include hazardous wastes discarded from

households, such as paint, cleaning solvents, and batteries,

and small quantities of hazardous materials discarded by

business and industry. Some states have their own definitions

of solid waste which may vary somewhat from the federal

definition. Federal oversight of solid-waste management is

the responsibility of the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA).

Facilities for the disposal of solid waste include munic-

ipal and industrial landfills, industrial surface im-

poundments, and incinerators. Incinerators that recover en-

ergy as a by-product of waste

combustion

are called

resource recovery

or waste-to-energy facilities. Sewage

sludge and agricultural waste may be applied to land surfaces

as fertilizers or

soil

conditioners. Other types of

waste

management

practices include

composting

, most com-

monly of separated organic wastes, and

recycling

. Some

solid waste ends up in illegal open dumps.

Three quarters of industrial nonhazardous waste comes

from four industries: iron and steel manufacturers,

electric

utilities

, companies making industrial inorganic

chemicals

,

and firms producing

plastics

and resins. About one-third

of industrial nonhazardous waste is managed on the site

where it is generated, and the rest is transported to off-site

municipal or industrial waste facilities. Although surveys

conducted by some states are beginning to fill in the gaps,

there is still not enough landfills and surface impoundments

for industrial solid wastes. Available data suggest there is

limited use of environmental controls at those facilities, but

there is insufficient information to determine the extent of

pollution

they may have caused.

The materials in municipal solid waste (MSW) are

discarded from residential, commercial, institutional, and

industrial sources. The materials include plastics, paper,

glass, metals, wood, food, and

yard waste

; the amount of

1324

each material is evaluated by weight or volume. The distinc-

tion between weight and volume is important when consid-

ering such factors as

landfill

capacity. For example, plastics

account for only about 8% of MSW by weight, but more

than 21% by volume. Conversely, glass represents about 7%

of the weight and only 2% of the volume of MSW.

MSW has recently been the focus of much attention

in the United States. Americans generated 4.5 lb (2 kg) per

day of MSW in 2000, an increase from 4.3 lb (1.95 kg) per

day 1990, 4.0 lb (1.8 kg) per day in 1980, and 2.7 lb (1.2

kg) per day in 1960. This increase has been accompanied

by tightening federal regulations concerning the use and

construction of landfills. The expense of constructing new

landfills to meet these regulations, as well as frequently

strong public opposition to new sites for them, have sharply

limited the number of disposal options available, and the

result is what many consider to be a solid waste disposal

crisis. The much-publicized “garbage barge” from Islip, New

York, which roamed the oceans from port to port during

1987 looking for a place to unload, has become a symbol of

this crisis.

The disposal of MSW is only the most visible aspect

of the waste disposal crisis; there are increasingly limited

disposal options for all the solid waste generated in America.

In response to this crisis, the EPA introduced a waste man-

agement hierarchy in 1989. The hierarchy places source

reduction and recycling above

incineration

and landfilling

as the preferred options for managing solid waste.

Recycling diverts waste already created away from in-

cinerators and landfills. Source reduction, in contrast, de-

creases the amount of waste created. It is considered the

best waste management option, and the EPA defines it as

reducing the quantity and toxicity of waste through the

design, manufacture, and use of products. Source reduction

measures include reducing packaging in products, reusing

materials instead of throwing them away, and designing

products to be long lasting. Individuals can practice

waste

reduction

by the goods they choose to buy and how they

use these products once they bring them home. Many busi-

nesses and industries have established procedures for waste

reduction, and some have reduced waste toxicity by using

less toxic materials in products and packaging. Source reduc-

tion can be part of an overall industrial pollution prevention

and waste minimization strategy, including recapturing pro-

cess wastes for

reuse

rather than disposal.

Some solid wastes are potentially threatening to the

environment

if thrown away but can be valuable resources

if reused or recycled. Used motor oil is one example. It

contains

heavy metals

and other hazardous substances that

can contaminate

groundwater

, surface water, and soils.

One gallon (3.8 L) of used oil can contaminate 1 million

gal (3.8 million L) of water, but these problems can be

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solid waste incineration

avoided and energy saved if used oil is rerefined into motor

oil or reprocessed for use as industrial fuel. Much progress

remains to be made in this area: of the 200 million gal (757

million L) of used oil generated annually by people who

change their own oil, only 10% is recycled.

Another solid waste with recycling potential are used

tires, which take up a large amount of space in landfills

and cause uneven settling. Tire stockpiles and open dumps

can be breeding grounds for mosquitoes, and are hazardous

if ignited, emitting noxious fumes that are difficult to

extinguish. Instead of being thrown away, tires can be

shredded and recycled into objects such as hoses and

doormats; they can also be mixed in road-paving materials

or used as fuel in suitable facilities. Whole tires can be

retreaded and reused on automobiles, or simply used for

such purposes as artificial reef construction. Other solid

wastes with potential for increased recycling include con-

struction and demolition wastes (building materials), house-

hold appliances, and waste wood.

The EPA recommends implementation of this waste

management hierarchy through integrated waste manage-

ment. The agency has encouraged businesses and commu-

nities to develop systems where components in the hierar-

chy complement each other. For example, removing

recyclables

before burning waste for

energy recovery

not only provides all the benefits of recycling, but it

reduces the amount of residual ash. Removing recyclable

materials that are difficult to burn, such as glass, increases

the

Btu

value of waste, thereby improving the efficiency

of energy recovery.

Some state and local governments have chosen to

conserve landfill space or reduce the toxicity of waste by

instituting bans on the burial or burning of certain materi-

als. The most commonly banned materials are automotive

batteries, tires, motor oil, yard waste, and appliances.

Where such bans exist, there is usually a complementary

system in place for either recycling the banned materials

or reusing them in some way. Programs such as these

usually compost yard waste and institute separate collections

for hazardous waste.

Perhaps because of the solid waste disposal crisis, there

have been recent changes in solid waste management prac-

tices. About 55.3% of MSW was buried in landfills in 2000,

down from 67% in 1990 and 81% in 1980. Recovery of

materials for recycling and composting also increased, with

64 million tons of material diverted away from landfills and

incinerators in 1999, up from 34 million tons in 1990. See

also Refuse-derived fuel; Sludge treatment and disposal;

Solid waste incineration; Solid waste landfilling; Solid waste

recycling and recovery; Solid waste volume reduction; Source

separation

[Teresa C. Donkin and Douglas Smith]

1325

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Blumberg, L., and R. Grottleib. War on Waste—Can America Win Its Battle

With Garbage? Covelo, CA: Island Press, 1988.

Neal, H. A., and J. R. Schubel. Solid Waste Management and the Environ-

ment: The Mounting Garbage and Trash Crisis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pren-

tice-Hall, 1987.

Robinson, W. D., ed. The Solid Waste Handbook. New York: Wiley, 1986.

Underwood, J. D., and A. Hershkowitz. Facts About U. S. Garbage Manage-

ment: Problems and Practices. New York: INFORM, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Glenn, J. “The State of Garbage in America.” Biocycle (May 1992).

O

THER

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Characterization of Municipal Solid

Waste in the United States: 1992 Update (Executive Summary). Washington,

DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, July 1992.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Solid Waste Disposal in the United

States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989.

Solid waste incineration

Incineration

is the burning of waste in a specially designed

combustion

chamber. The idea of burning

garbage

is not

new, but with the increase in knowledge about toxic

chemi-

cals

known to be released during burning, and with the

increase in the amount of garbage to be burned, incineration

now is done under controlled conditions. It has become the

method of choice of many

waste management

companies

and municipalities.

According to the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA), there are 135 operational waste combustion facilities

in the United States. About 120 of them recover energy,

and in all, the facilities process about 14.5% of the nation’s

232 million tons (210.5 million metric tons) of

municipal

solid waste

produced each year.

There are several types of combustion facilities in oper-

ation. At incinerators, mixed trash goes in one end unsorted,

and it is all burned together. The resulting ash is typically

placed in a

landfill

.

At

mass burn

incinerators, also known as mass burn

combustors, the heat generated from the burning material

is turned into useable electricity. Mixed garbage burns in a

special chamber where temperatures reach at least 2000°F

(1093 °C). The byproducts are ash, which is landfilled, and

combustion gases. As the hot gases rise from the burning

waste, they heat water held in special tubes around the

combustion chamber. The boiling water generates steam

and/or electricity. The gases are filtered for contaminants

before being released into the air.

Modular combustion systems typically have two com-

bustion chambers: one to burn mixed trash and another to

heat gases. Energy is recovered with a heat recovery steam

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Solid waste incineration

generator. Refuse-derived fuel combustors burn presorted

waste and convert the resulting heat into energy. In all,

incinerators in this country in 1992 typically consumed

80,100 tons (72,730 metric tons) of waste each day, and

generated the annual equivalent of 16.4 million megawatts

of usable power, equal to roughly 30 million barrels of oil.

One major problem with incineration is

air pollution

.

Even when equipped with

scrubbers

, many substances,

some of them toxic, are released into the

atmosphere

.In

the United States, emissions from incinerators are among

targets of the

Clean Air Act

, and research continues on ways

to improve the efficiency of incinerators. For now, however,

many environmentalists protest the use of incinerators.

Incinerators burning municipal solid waste produce

the pollutants

carbon monoxide

,

sulfur dioxide

, and par-

ticulates containing

heavy metals

. The generation of pol-

lutants can be controlled by proper operation and by the

proper use of air

emission

control devices, including dry

scrubbers, electrostatic precipitators, fabric

filters

, and

proper stack height.

Dry scrubbers wash

particulate

matter and gases from

the air by passing them through a liquid. The scrubber

removes

acid

gases by injecting a lime

slurry

into a reaction

tower through which the gases flow. A salt powder is pro-

duced and collected along with the

fly ash

. The lime also

causes small particles to stick together, forming larger parti-

cles that are more easily removed.

Electrostatic precipitators use high voltage to nega-

tively charge dust particles, then the charged particulates are

collected on positively charged plates. This device has been

documented as removing 98% of particulates, including

heavy metals; nearly 43% of all existing facilities use this

method to control air

pollution

.

Fabric filters or

baghouses

consist of hundreds of

long fabric bags made of heat-resistant material suspended

in an enclosed housing which filters particles from the gas

stream. Fabric filters are able to trap fine, inhalable particles,

up to 99% of the particulates in the gas flow coming out of

the scrubber, including condensed toxic organic and heavy

metal compounds. Stack height is an extra precaution taken

to assure that any remaining pollutants will not reach the

ground in a concentrated area.

Using the

Best Available Control Technology

(BAT), the National Solid Wastes Management Association

states more than 95% of gases and fly ash are captured and

removed. However, such state-of-the-art facilities are more

the exception than the rule. In a study of 15 mass burn and

refuse-derived fuel plants of varying age, size, design, and

control systems, the environmental research group

INFORM

found that only one of the 15 achieved the emission levels

set by the group for six primary air pollutants (dioxins and

furans

, particulates,

carbon

monoxide, sulfur dioxide,

hy-

1326

drogen

chloride, and

nitrogen oxides

). Six plants did not

meet any. Only two employed the safest ash management

techniques, and the EPA is still trying to define standards

for air emissions from municipal incinerators.

Ash is the solid material left over after combustion in

the incinerator. It is composed of noncombustible inorganic

materials that are present in cans, bottles, rocks and stones,

and complex organic materials formed primarily from carbon

atoms that escape combustion. Municipal solid waste ash

also can contain

lead

and

cadmium

from such sources as

old appliances and car batteries.

Bottom ash, the unburned and unburnable matter left

over, comprises 75–90% of all ash produced in incineration.

Fly ash is a powdery material suspended in the

flue gas

stream and is collected in the

air pollution control

equip-

ment. Fly ash tends to have higher concentrations of certain

metals and organic materials, and comprises 10–25% of total

ash generated.

The greatest concern with ash is proper disposal and

the potential for harmful substances to be released into the

groundwater

. Federal regulations governing ash are in

transition because it is not known whether ash should be

regulated as a hazardous or nonhazardous waste as specified

in the

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

(RCRA)

of 1976.

EPA draft guidelines for handling ash include: ash

containers and transport vehicles must be leak-tight;

groundwater monitoring

must be performed at disposal

sites; and liners must be used at all ash disposal landfills.

While waste-to-energy plants can decrease the volume

of solid waste by 60–90% and at the same time recover

energy from discarded products, the cost of building such

facilities is too high for most municipalities. The $400 mil-

lion price tag for a large plant is prohibitive, even if the

revenue from the sale of energy helps offset the cost. But

without a strong market for produced energy, the plant may

not be economically feasible for many areas.

The Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA),

enacted in 1979, helps to ensure that small power generators,

including waste-to-energy facilities, will have a market for

produced energy. PURPA requires utilities to purchase such

energy from qualifying facilities at avoided costs, that is, the

cost avoided by not generating the energy themselves. Some

waste-to-energy plants are developing markets themselves

for steam produced. Some facilities supply steam to industrial

plants or district heating systems.

Another concern over the use of incinerators to solve

the garbage dilemma in the United States is that materials

incinerated are resources lost—resources that must be recre-

ated with a considerable effort, high expense, and potential

environmental damage. From this point of view, incineration

represents a failure of waste disposal policy. Waste disposal,