Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

The Global 2000 Report

and kidney tumors in male rats, it is considered to be a

potential human

carcinogen

.

Exposure to high concentrations of tetrachloroethy-

lene, especially in poorly ventilated areas, can cause nose and

throat irritation and dizziness, headache, sleepiness, confu-

sion, nausea, difficulty in speaking and walking, uncon-

sciousness, and death. Severe skin irritation may result from

repeated or extended skin contact with tetrachloroethylene.

The

Occupational Safety and Health Administra-

tion

(OSHA) has set a limit of 100 ppm for an eight-hour

workday over a 40-hour workweek. The

National Institute

for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH) recom-

mends that because tetrachloroethylene is a potential carcin-

ogen, levels in the workplace should be kept as low as possi-

ble. Since tetrachloroethylene is considered a hazardous air

pollutant under the U.S.

Clean Air Act

, a federal rule went

into effect in 1996 for dry cleaning establishments that regu-

lates operating procedures and equipment type and use, with

the goal of reducing tetrachloroethylene emissions from

those facilities. However, tetrachloroethylene does not con-

tribute to stratospheric

ozone

depletion and has been ap-

proved by the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) for use as a replacement for ozone-depleting solvents.

Tetrachloroethylene can be released into air and water

through dry cleaning and industrial metal cleaning or finish-

ing activities.

Water pollution

can result from tetrachloro-

ethylene

leaching

from vinyl pipe liners. Tetrachloroethy-

lene released into

soil

will readily evaporate or may leach

slowly to groundwater, for it biodegrades slowly in soil.

When released into water bodies, tetrachloroethylene will

primarily evaporate and has little potential for accumulating

in aquatic life.

The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL), which is

an enforceable standard for tetrachloroethylene in drinking

water, has been set at 5

parts per billion

(ppb) by the EPA.

This is the lowest level of tetrachloroethylene, given present

technologies and resources, that a

water treatment

system

can be expected to achieve. In contrast to the enforceable

level of tetrachloroethylene is the desired level in drinking

water, which is referred to as the Maximum Contaminant

Level Goal (MCLG). This been set at zero because of possi-

ble health risks. If levels of tetrachloroethylene are too high

in a drinking water source, it can be removed through the

use of granular activated

carbon filters

and packed tower

aeration

, which is a way to remove chemicals from ground

water by increasing the surface area of the contaminated

water that is exposed to air. Tetrachloroethylene wastes are

classified as hazardous under the

Resource Conservation

and Recovery Act

(RCRA) and must be stored, transported,

and disposed of according to RCRA requirements.

[Judith L. Sims]

1387

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Leeds, Michelle S. Perchloroethylene (Carbon Dichloride, Tetrachloroethylene,

Drycleaner, Fumigant): Effects on Health and Work. Washington, DC: Abbe

Publishing Association, 1995.

O

THER

Halogenated Solvents Industry Alliance. Perchloroethylene: White Paper. No-

vember 1999 [cited June 22, 2002]. <http://www.hsia.org/white_papers/

perc.htm>.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Consumer Factsheet on: Tetrachloro-

ethylene. May 22, 2002 [cited June 22, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/safew-

ater/dwh/c-voc/tetrachl.html>.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Rule and Implementation Informa-

tion for Perchloroethylene Dry Cleaning Facilities. June 10, 2002 [cited June

23, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/ttn/atw/dryperc/dryclpg.html>.

Tetraethyl lead

Tetraethyl

lead

is an organometallic compound with the

chemical formula (C

2

H

5

)

4

Pb. In 1922, automotive engineers

found that the addition of a small amount of this compound

to

gasoline

improves engine performance and reduces

knocking. Knocking is a physical phenomenon that results

when low-octane gasoline is burned in an internal

combus-

tion

engine. Until 1975, tetraethyl lead was the most com-

mon additive used to reduce knocking in motor fuels. This

additive presents an environmental hazard, however, since

lead is expelled into the

environment

during operation of

automobile

engines using leaded fuels. Given the growing

concern about the health effects of lead, the compound has

now been banned for use in gasolines in the United States.

See also Air pollution; Air pollution index; Emission;

Gasohol

The Coastal Society

see

Coastal Society, The

The Cousteau Society

see

Cousteau Society, The

The Global 2000 Report

Released in July 1980, this landmark study warned of grave

consequences for humanity if changes were not made in

environmental policy

around the globe. Prepared over a

three year period by the President’s

Council on Environmen-

tal Quality

(CEQ) in cooperation with the U.S. Department

of State and other federal agencies, this was the first compre-

hensive and integrated report by the United States or any

other government projecting long-term environmental, re-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Thermal plume

source, and population trends. It was the subject of extensive

publicity, attention, and debate, influencing political leaders

and policy makers the world over.

In announcing release of the report, CEQ warned that

“U.S. Government projections show that unless the nations

of the world act quickly and decisively to change current

policies, life for most of the world’s people will be more

difficult and more precarious in the year 2000.”

Specifically, the study states that “If present trends

continue, the world in 2000 will be more crowded, more

polluted, less stable ecologically, and more vulnerable to

disruption than the world we live in now...For hundreds of

millions of the desperately poor, the outlook for food and

other necessities of life will be no better. For many, it will

be worse.”

Among the report’s findings and conclusions were the

following:

O

The world will add almost 100 million people a year to its

population, which will grow from 4.5 billion in 1980 to 6

billion in 2000;

O

Billions of tons and millions of acres of cropland are being

lost each year to

erosion

and development, and

desertifi-

cation

is claiming an area the size of Maine each year;

O

The planet’s genetic resource base is being severely de-

pleted, and between 500,000 and 2 million plant and animal

species--15 to 20 percent of all

species

on the earth--

could be extinguished by the year 2000;

O

Periodic and severe water shortages will be accompanied

by a doubling of the demand for water from 1971 levels;

increased burning of

coal

and other

fossil fuels

will cause

acid

rain-induced damage to lakes, crops, forests, and

buildings, and could lead to catastrophic

climate

change

(global warming) “that could have highly disruptive effects

on world agriculture.”

O

Depletion of the stratospheric

ozone

layer by industrial

chemicals

(

chlorofluorocarbons

) could cause serious

damage to food crops and human health.

The report noted the ongoing worldwide efforts to

protect and replant forests, conserve energy, promote

family

planning

and birth control programs, prevent

soil

erosion

and desertification, and find alternatives to the present reli-

ance on toxic pesticides and nonrenewable, polluting energy

sources such as

petroleum

and coal. But the study empha-

sized that “Encouraging as these developments are, they are

far from adequate to meet the global challenges projected in

this study. Vigorous, determined new initiatives are needed if

worsening poverty and human suffering,

environmental

degradation

, and international tension and conflicts are to

be prevented.”

Some skeptics criticized the report’s pessimistic tone

and dire warnings as exaggerated and overblown, and its

1388

recommendations later were largely ignored by the Reagan

and Bush administrations. However, it is now apparent that

its major points were not only well founded but may turn out

to be far too conservative, rather than radical and alarmist. See

also Deforestation; Drought; Energy conservation; Environ-

mental policy; Gene pool; Greenhouse effect; Ozone layer

depletion; Pollution control; Population growth; Sustainable

agriculture; Water allocation

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Council on Environmental Quality. The Global 2000 Report to the President.

3 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1980.

The Nature Conservancy

see

Nature Conservancy, The

The Ocean Conservatory

see

Ocean Conservatory, The

Thermal plume

Water used for cooling by

power plants

and factories is

commonly returned to its original source at a temperature

greater than its original temperature. This heated warm

water leaves an outlet pipe in a stream-like flow known as

a thermal

plume

. The water within the plume is significantly

warmer than the water immediately adjacent to it. Thermal

plumes are environmentally important because the introduc-

tion of heated water into lakes or slow-moving rivers can

have adverse effects on aquatic life. Warmer temperatures

decrease the solubility of oxygen in water, thus lowering the

amount of

dissolved oxygen

available to aquatic organ-

isms. Warmer water also causes an increase in the

respira-

tion

rates of these organisms, and they deplete the already-

reduced supply of oxygen more quickly. Warmer water also

makes aquatic organisms more susceptible to diseases,

para-

sites

, and toxic substances. See also Thermal pollution

Thermal pollution

The

combustion

of

fossil fuels

always produces heat, some-

times as a primary, desired product, and sometimes as a

secondary, less-desired by-product. For example, families

burn

coal

, oil,

natural gas

, or some other fuel to heat their

homes. In such cases, the production of heat is the object

of burning a fuel. Heat is also produced when fossil fuels

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Thermal pollution

are burned to generate electricity. In this case, heat is a by-

product, not the main reason that fuels are burned.

Heat is produced in a number of other common pro-

cesses. For example, electricity is also generated in nuclear

power plants

, where no combustion occurs. The decay of

organic matter in landfills also releases heat to the

atmo-

sphere

.

It is clear, therefore, that a vast array of human activi-

ties result in the release of heat to the

environment

.As

those activities increase in number and extent, so does the

amount of heat released. In many cases, heat added to the

environment begins to cause problems for plants, humans,

or other animals. This effect is then known as thermal

pol-

lution

.

One example of thermal pollution is the development

of urban heat islands. An

urban heat island

consists of a

dome of warm air over an urban area caused by the release

of heat in the region. Since more human activity occurs

in an urban area than in the surrounding rural areas, the

atmosphere over the urban area becomes warmer than it is

over the rural areas.

It is not uncommon for urban heat islands to produce

measurable

climate

changes. For example, the levels of pol-

lutants trapped in an urban heat island can reach 5–25%

greater than the levels over rural areas. Fog and clouds may

reach twice the level of comparable rural areas, wind speeds

may be reduced by up to 30%, and temperatures may be

0.9–3.6°F (0.5°–2°C) higher than in surrounding rural areas.

Such differences may cause both personal discomfort and,

in some cases, actual health problems for those living within

an urban heat island.

The term thermal pollution has traditionally been used

more often to refer to the heating of lakes, rivers, streams, and

other bodies of water, usually by electric power-generating

plants or by factories. For example, a one-megawatt

nuclear

power

plant may require 1.3 billion gal (4.9 billion L) of

cooling water each day. The water used in such a plant has

its temperature increased by about 30.6°F (17°C) during the

cooling process. For this reason, such plants are usually built

very close to an abundant water supply such as a lake, a large

river, or the ocean.

During its operation, the plant takes in cool water

from its source, uses it to cool its operations, and then returns

the water to its original source. The water is usually recycled

through large cooling towers before being returned to the

source, but its temperature is still likely to be significantly

higher than it was originally. In many cases, an increase of

only a degree or two may be “significantly higher” for organ-

isms living in the water.

When heated water is released from a plant or factory,

it does not readily mix with the cooler water around it.

Instead, it forms a stream-like mass known as a

thermal

1389

plume

that spreads out from the outflow pipes. It is in

this thermal

plume

that the most severe effects of thermal

pollution are likely to occur. Only over an extended period

of time does the plume gradually mix with surrounding

water, producing a mass of homogenous temperature.

Heating the water in a lake or river can have both

beneficial and harmful effects. Every

species

of plant and

animal has a certain range that is best for its survival. Raising

the temperature of water may cause the death of some organ-

isms, but may improve the environment of other species.

Pike, perch, walleye, and small mouth bass, for example,

survive best in water with a temperature of about 84°F

(29°C), while catfish, gar, shad, and other types of bass

prefer water that is about 10°F (5.5°C) warmer.

Spawning and egg development are also very sensitive

to water temperature. Lake trout, walleye, Atlantic

salmon

,

and northern pike require relatively low temperatures (about

48°F/9°C), while the eggs of perch and small mouth bass

require a much higher temperature, around 68°F (20°C).

Clearly, changes in water temperature produced by a

nuclear power plant, for example, is likely to change the mix

of organisms in a waterway.

Of course, large increases in temperature can have

disastrous effects on an aquatic environment. Few organisms

could survive an accident in which large amounts of very

warm water were suddenly dumped into a lake or river. This

effect can be observed especially when a power plant first

begins operation, when it shuts down for repairs, and when

it restarts once more. In each case, a sudden change in water

temperature can cause the death of many individuals and

lead to a change in the make-up of an aquatic community.

Sudden temperature changes of this kind produce an effect

known as thermal shock. To avoid the worst effects of ther-

mal shock, power plants often close down or re-start slowly,

reducing or increasing temperature in a waterway gradually

rather than all at once.

One inevitable result of thermal pollution is a reduc-

tion in the amount of

dissolved oxygen

in water. The

amount of any gas that can be dissolved in water varies

inversely with the temperature. As water is warmed, there-

fore, it is capable of dissolving less and less oxygen. Organ-

isms that need oxygen to survive will, in such cases, be less

able to survive.

Water temperatures can have other, less-expected ef-

fects as well. As an example, trout can swim less rapidly in

water above 66°F (19°C), making them less efficient preda-

tors. Organisms may also become more subject to disease

in warmer water. The bacterium Chondrococcus columnaris is

harmless to fish at temperatures of less then 50°F (10°C).

Between temperatures of 50°–70°F (10°–21°C), however, it

is able to invade through wounds in a fish’s body. It can

even attack healthy tissue at temperatures above 70°F (21°C).

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Thermal stratification (water)

The loss of a single aquatic species or the change in

the structure of an aquatic community can have far-reaching

effects. Each organism is part of a

food chain/web

. Its loss

may mean the loss of other organisms farther up the web

who depend on it as a source of food.

The water heated by thermal pollution has a number

of potentially useful applications. For example, it may be

possible to establish aquatic farms where commercially desir-

able fish and shellfish can be raised. The Japanese have been

especially successful in pursuing this option. Some experts

have also suggested using this water to heat buildings, re-

move snow, fill swimming pools, use for

irrigation

, de-ice

canals, and operate industrial processes that have modest

heat requirements.

The fundamental problem with most of these sugges-

tions is that waste heat has to be used where it is produced.

It might not be practical to build a factory close to a nuclear

power plant solely for the purpose of using heat generated

by the plant. As a result, few of the suggested uses for waste

heat have actually been acted upon.

There are no easy solutions to the problems of thermal

pollution. To the extent that industries and utilities use less

energy or begin to use it more efficiently, a reduction in

thermal pollution should result as a fringe benefit.

The other option most often suggested is to do a better

job of cooling water before it is returned to a river, lake, or

the ocean. This goal could be accomplished by enlarging

the cooling towers that most plants already have. However,

those towers might have to be as tall as a 30-story building,

in which case they would create new problems. In cold

weather, for example, the water vapor released from such

towers could condense to produce fog, creating driving haz-

ards over an extended area.

Another approach is to divert cooling water to large

artificial ponds where it can remain until its temperature

has dropped sufficiently. Such cooling ponds are in use in

some locations, but are not very attractive alternatives be-

cause they require so much space. A one-megawatt plant,

for example, would require a cooling pond with 1,000-2,000

acres (405-810 ha) of surface area. In many areas, the cost

of using land for this purpose would be too great to justify

the procedure.

Some people have also used the term thermal pollution

to describe changes in the earth’s climate that may result

from human activities. The large quantities of fossil fuels

burned each year release a correspondingly large amount of

carbon dioxide

to the earth’s atmosphere. This

carbon

dioxide, in turn, may increase the amount of heat trapped

in the atmosphere through the

greenhouse effect

. One

possible result of this change could be a gradual increase in

the earth’s annual average temperature. A warmer climate

might, in turn, have possibly far-reaching and largely un-

1390

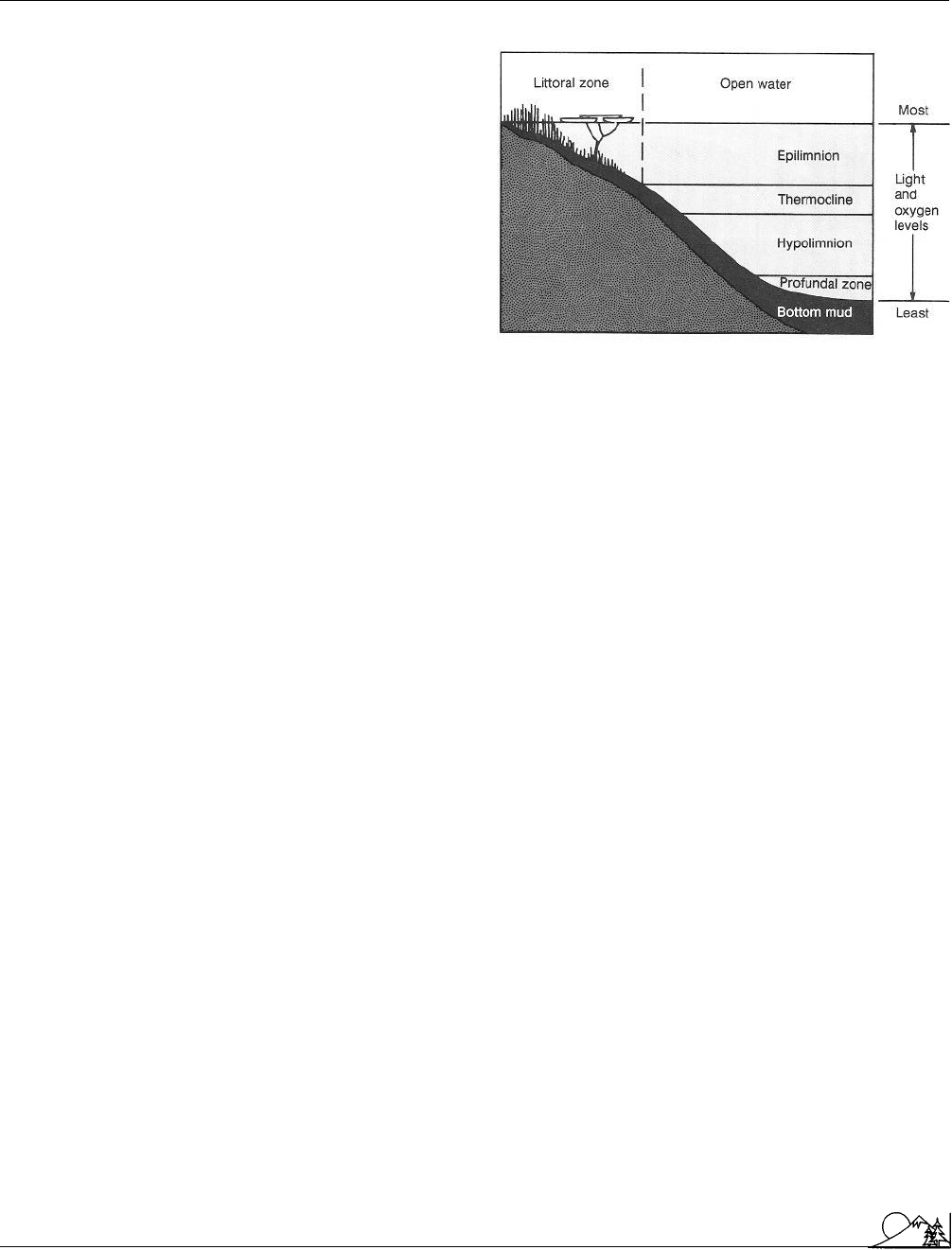

Thermal stratification of a deep lake. (McGraw-

Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

known effects on agriculture, rainfall, sea levels, and other

phenomena around the world. See also Alternative energy

sources; Industrial waste treatment

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Harrison, R. M., ed. Pollution: Causes, Effects, and Control. Cambridge:

Royal Society of Chemistry, 1990.

Langford, T. E., ed. Ecological Effects of Thermal Discharges. New York:

Elsevier Science, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Hudson, J., and J. B. Cravens. “Thermal Effects.” Water Environment

Research 64 (June 1992): 570–81.

Thermal stratification (water)

The development of relatively stable, warmer and colder

layers within a body of water. Thermal

stratification

is

related to incoming heat, water depth, and degree of water

column mixing. Deep, large lakes such as the

Great Lakes

receive insufficient heat to warm the entire water column

and lack adequate physical turnover or mixing of the water

for uniform temperature distribution. Thus, they have an

upper layer of water that is warmed by surface heating (epi-

limnion) and a lower layer of much colder water (hypolim-

nion), separated by a layer called the

thermocline

in which

the temperature decreases rapidly with depth. Both daily

and seasonal variations in heat input can promote thermal

stratification. Stratification in summer followed by mixing

in the fall is a phenomenon commonly observed in temperate

lakes of moderate depths (over 33 ft [10 m]).

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Thermodynamics, Laws of

Thermocline

A thermocline is a zone of rapid temperature change with

depth in a body of water. It is the boundary between two

layers of water that have different temperatures, in a lake,

estuary

, or an ocean. The thermocline is marked by a dra-

matic change in temperature, where the water temperature

changes at least one Celsius degree with every meter of depth.

Because of density differences associated with a change in

temperature, thermoclines can prevent mixing of nutrients

from deep to shallow water, and can therefore cause the

surface waters of some lakes and ocean to have very low

primary productivity

, even when there is sufficient light

for

phytoplankton

to grow. In other areas, the thermocline

can prevent mixing of oxygen-rich surface waters with bot-

tom waters in which oxygen has been depleted as a result

of high rates of

decomposition

related to eutrophication.

In temperate freshwater lakes, the thermocline is disrupted

in fall when the surface waters become denser as decreasing

air temperatures cool the surface of the lake. Cooler water

is denser and sinks, thereby causing warmer bottom water

to rise to the surface and mix nutrients throughout the water

column.

[Marie H. Bundy]

Thermodynamics, Laws of

One way of understanding the

environment

is to under-

stand the way matter and

energy flow

through the natural

world. For example, it helps to know that a fundamental

law of

nature

is that matter can be neither created nor

destroyed. That law describes how humans can never really

“throw something away.” When wastes are discarded, they

do not just disappear. They may change location or change

into some other form, but they still exist and are likely to

have some impact on the environment.

Perhaps the most important laws involving energy are

the laws of thermodynamics. These laws were first discovered

in the nineteenth century by scientists studying heat engines.

Eventually, it became clear that the laws describing energy

changes in these engines apply to all forms of energy.

The first law of thermodynamics says that energy can

be changed from one form to another, but it can be neither

created nor destroyed. Energy can occur in a variety of forms

such as thermal (heat), electrical, magnetic, nuclear, kinetic,

or chemical. The conversion of one form of energy to another

is familiar to everyone. For example, the striking of a match

involves two energy conversions. In the first conversion, the

kinetic energy involved in rubbing a match on a scratch pad

is converted into a chemical change in the match head. That

1391

chemical change results in the release of chemical energy

that is then converted into heat and light energy.

Most energy changes on the earth can be traced back

to a single common source: the sun. The following describes

the movement of energy through a common environmental

pathway, the production of food in a green plant:

solar

energy

reaches the earth and is captured by the leaves of a

green plant. Individual cells in the leaves then make use

of solar energy to convert

carbon dioxide

and water to

carbohydrates in the process known as

photosynthesis

. The

solar energy is converted to a new form, chemical energy,

that is stored within carbohydrate molecules.

“Stored” energy is called potential energy. The term

means that energy is available to do work, but is not currently

doing so. A rock sitting at the top of a hill has potential

energy because it has the capacity to do work. Once it starts

rolling down the hill, it uses a different type of energy to

push aside plants, other rocks, and other objects.

Chemical energy stored within molecules is another

form of potential energy. When chemical changes occur,

that energy is released to do some kind of work.

Energy that is actually being used is called kinetic

energy. The term kinetic refers to motion. A rock rolling

down the hill converts potential energy into the energy of

motion, kinetic energy. The first law of thermodynamics

says that, theoretically, all of the potential energy stored in

the rock can be converted into kinetic energy, without any

loss of energy at all.

One can follow, therefore, the movement of solar en-

ergy through all parts of the environment and show how it

is eventually converted into the chemical energy of carbohy-

drate molecules, then into the chemical energy of molecules

in animals who eat the plant, then into the kinetic energy

of animal movement, and so on.

Environmental scientists sometimes put the first law

into everyday language by saying that “there is no such thing

as a free lunch.” By that expression, they mean that in order

to produce energy, energy must be used. For many years,

for example, scientists have known that vast amounts of oil

can be found in rock-like formations known as

oil shale

,

but the amount of energy needed to extract that oil by any

known process is much greater than the energy that could

be obtained from it.

Scientists apply the first law of thermodynamics to an

endless variety of situations. A nuclear engineer, for example,

can calculate the amount of heat energy that can be obtained

from a reactor using nuclear materials (nuclear energy) and

the amount of electrical energy that can be obtained from

that heat energy.

However, in all such calculations, the engineer also

has to take into consideration the second law of thermody-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Thermodynamics, Laws of

namics. This law states that in any energy conversion, there

is always some decrease in the amount of usable energy.

A familiar example of that law is the incandescent

light bulb. Light is produced in the bulb when a thin wire

inside is heated until it begins to glow. Electrical energy is

converted into both heat energy and light energy in the wire.

As far as the bulb is concerned, the desired conversion

is electrical energy to light energy. The heat that is produced,

while necessary to get the light, is really “waste” energy. In

fact, the incandescent lightbulb is a very inefficient device.

More than 90% of the electrical energy that goes into the

bulb comes out as heat. Less than 10% is used for the

intended purpose, making light.

Examples of the second law can be found everywhere

in the natural and human-made environment. And, in many

cases, they are the cause of serious problems.

If one follows the movement of solar energy through

the environment again, the amazing observation is how much

energy is wasted at each stage. Although green plants do con-

vert solar energy to chemical energy, they do not achieve 100%

efficiency. Some of the solar energy is used to heat a plant’s

leaf and is converted, therefore, to heat energy. As far as the

plant is concerned, that heat energy is wasted. By the time

solar energy is converted to the kinetic energy used by a school

child in writing a test, more than 99% of the original energy

received from the sun has been wasted.

Some people use the second law of thermodynamics

to argue for less meat-eating by humans. They point out

how much energy is wasted in using grains to feed cattle.

If humans would eat more plants, they say, less energy would

be wasted and more people could be fed with available re-

sources.

The second law explains other environmental prob-

lems as well. In a

nuclear power

plant, energy conversion

is relatively low, around 30%. That means that about 70%

of the nuclear energy stored in radioactive materials is even-

tually converted not to electricity, but to waste heat. Large

cooling towers have to be built to remove that waste heat.

Often, the waste heat is carried away into lakes, rivers, and

other bodies of water. The waste heat raises the temperature

of this water, creating problems of

thermal pollution

.

Scientists often use the concept of entropy in talking

about the second law. Entropy is a measure of the disorder

or randomness of a system and its surroundings. A beautiful

glass vase is an example of a system with low entropy because

the atoms of which it is made are carefully arranged in a

highly structured system. If the vase is broken, the structure

is destroyed and the atoms of which it was made are more

randomly distributed.

The second law says that any system and its surround-

ings tends naturally to have increasing entropy. Things tend

1392

to spontaneously “fall apart” and become less organized. In

some respects, the single most important thing that humans

do to the environment is to appear to reverse that process.

When they build new objects from raw materials, they tend

to introduce order where none appeared before. Instead of

iron ore being spread evenly through the earth, it is brought

together and arranged into a new

automobile

, a new build-

ing, a piece of art, or some other object.

But the apparent decrease in entropy thus produced is

really misleading. In the process of producing this order, hu-

mans have also brought together, used up, and then dispersed

huge amounts of energy. In the long run, the increase in en-

tropy resulting from energy use exceeds the decrease produced

by construction. In the end, of course, the production of order

in manufactured goods is only temporary since these objects

eventually wear out, break, fall apart, and return to the earth.

For many people, therefore, second law of thermody-

namics is a very gloomy concept. It suggests that the universe

is “running down.” Every time an energy change occurs, it

results in less usable energy and more wasted heat.

People concerned about the environment do well,

therefore, to know about the law. It suggests that humans

think about ways of using waste heat. Perhaps there would

be a way, for example, of using the waste heat from a nuclear

power plant to heat homes or commercial buildings. Tech-

niques for making productive use of waste heat are known

as

cogeneration

.

Another way to deal with the problem of waste heat

in energy conversions is to make such conversions more

efficient or to find more efficient methods of conversion.

The average efficiency rate for

power plants

using

fossil

fuels

is only 33%. Two-thirds of the chemical energy stored

in

coal

, oil, and

natural gas

is, therefore, wasted. Methods

for improving the efficiency of such plants would obviously

provide a large environmental and economic benefit.

New energy conversion devices can also help. Fluores-

cent light builds, for example, are far more efficient at con-

verting electrical energy into light energy than are incandes-

cent bulbs. Experts point out that simply replacing existing

incandescent light bulbs with fluorescent lamps would make

a significant contribution in reducing the nation’s energy

expenditures. See also Alternative energy sources; Energy

and the environment; Energy flow; Environmental science;

Pollution

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Joesten, M. D., et al. World of Chemistry. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1991.

———. Living in the Environment. 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth,

1992.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Third World pollution

Miller Jr., F. College Physics. 6th ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanov-

ich, 1987.

Miller Jr., G. T. Energy and Environment: The Four Energy Crises. 2nd ed.

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1980.

Thermoplastics

A thermoplastic is any material that can be heated and

cooled a number of times. Some common thermoplastics

are

polystyrene

, polyethylene, the acrylics, the polyvinyl

plastics

, and polymeric derivatives of cellulose. Thermoplas-

tics are attractive commercial and industrial materials be-

cause they can be molded, shaped, extruded, and otherwise

formed while they are molten. A few of the products made

from thermoplastics are bottles, bags, toys, packing materi-

als, food wrap, adhesives, yarns, and electrical insulation.

The ability to be reshaped is also an environmental benefit.

Waste thermoplastics can be separated from other solid

wastes and recycled by reforming them into new products.

See also Recyclables; Recycling; Solid waste; Solid waste

recycling and recovery; Solid waste volume reduction

Thermosetting polymers

Thermosetting polymers are compounds that solidify, or

“set,” after cooling from the molten state and then cannot

be remelted. Some typical thermosetting polymers are the

epoxys, alkyds, polyurethanes,

furans

, silicones, polyesters,

and phenolic

plastics

. Products made from thermosetting

polymers include: radio cases, buttons, dinnerware, glass

substitutes, paints, synthetic

rubber

, insulation, and syn-

thetic body parts. Because they cannot be recycled and do not

readily decompose, thermosetting polymers pose a serious

environmental hazard. They contribute significantly, there-

fore, to the problem of

solid waste

disposal and, in some

cases, pose a threat to

wildlife

who swallow or become

ensnared in plastic materials. See also Solid waste incinera-

tion; Solid waste recycling and recovery; Solid waste volume

reduction

Third World

The unofficial but common term “Third World” refers to

the world’s less wealthy and

less developed countries

.In

the decades after World War II, the term was developed in

recognition of the fact that these countries were emerging

from colonial control and were prepared to play an indepen-

dent role in world affairs. In academic discussions of the

world as a single, dynamic system, or world systems theory,

the term distinguishes smaller, nonaligned countries from

powerful capitalist countries (the

First World

) and from the

1393

now disintegrating communist bloc (the

Second World

).

In more recent usage, the term has come to designate the

world’s less developed countries that are understood to share

a number of characteristics, including low levels of industrial

activity, low per capita income and literacy rates, and rela-

tively poor health care that leads to high infant

mortality

rates and short life expectancies. Often these conditions

accompany inequitable distribution of land, wealth, and po-

litical power and an economy highly dependent on exploita-

tion of

natural resources

.

Third World pollution

As the countries of the

Third World

struggle with

popula-

tion growth

, poverty, famines, and wars, their residents are

discovering the environmental effects of these problems, in

the form of increasing air, water, and land

pollution

. Pollu-

tion is almost unchecked in many developing nations, where

Western nations dump toxic wastes and untreated sewage

flows into rivers. Many times, the choice for Third World

governments is between poverty or poison, and basic human

needs like food, clothing, and shelter take precedence.

Industrialized nations often dump wastes in devel-

oping countries where there is little or no environmental

regulation, and governments may collect considerable fees

for accepting their

garbage

. In 1991, World Watch magazine

reported that Western companies dumped more than 24

million tons (22 million metric tons) of

hazardous waste

in Africa alone during 1988.

Companies can also export industrial hazards by mov-

ing their plants to countries with less restrictive

pollution

control

laws than industrialized nations. This was the case

with Union Carbine, which moved its chemical manufactur-

ing plant to

Bhopal, India

, to manufacture a product it was

not allowed to make in the United States. As Western na-

tions enact laws promoting environmental and worker safety,

more manufacturers have moved their hazardous and pollut-

ing factories to

less developed countries

, where there are

little or no environmental or occupations laws, or no enforce-

ment agencies. Hazardous industries such as textile,

petro-

chemical

, and chemical production, as well as smelting and

electronics, have migrated to Latin America, Africa, Asia,

and Eastern Europe.

For example, IBM, General Motors, and Sony have

established manufacturing plants in Mexico, and some of

these have created severe environmental problems. At least

10 million gal (38 million L) of the factories’ raw sewage is

discharged into the Tijuana River daily. Because pollution

threatens San Diego beaches, most of the cleanup is paid for

by the United States and California governments. Although

consumers pay less for goods from these companies, they

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Third World pollution

are paying for their manufacture in the form of higher taxes

for environmental cleanup.

Industries with shrinking markets in developed coun-

tries due to environmental concerns have begun to advertise

vigorously in the Third World. For example, DDT produc-

tion, led by United States and Canadian companies, is at

an all-time high even though it is illegal to produce or use

the

pesticide

in the United States or Europe since the 1970s.

DDT is widely used in the Third World, especially in Latin

America, Africa, and on the Indian subcontinent.

Industrial waste is handled more recklessly in underde-

veloped countries. The New River, for example, which flows

from northern Mexico into southern California before

dumping into the Pacific Ocean, is generally regarded as

the most polluted river in North America due to lax enforce-

ment of environmental standards in Mexico.

Industrial pollution in Third World countries is not

their only environmental problem. Now, in addition to wor-

rying about the environmental implications of

deforesta-

tion

,

desertification

, and

soil erosion

, developing coun-

tries are facing threats of pollution that come from

development, industrialization, poverty, and war.

The number of gasoline-powered vehicles in use world-

wide is expected to double to one billion in the next 40 years,

adding to

air pollution

problems. Mexico City, for example,

has had air pollution episodes so severe that the government

temporarily closed schools and factories. Much of the auto-

industry growth will take place in developing countries, where

the

automobile

population is rapidly increasing.

In the Third World, the effects of

water pollution

are

felt in the form of high rates of death from

cholera

, typhoid,

dysentery, and diarrhea from viral and bacteriological sources.

More than 1.7 billion people inthe Third World have an inad-

equate supply of safe drinking water. In India, for example,

114 towns and cities dump their human waste and other un-

treated sewage directly into the Ganges River. Of 3,119 In-

dian towns and cities, only 209 have partial

sewage treat-

ment

, and only eight have complete treatment.

Zimbabwe’s industrialization has created pollution

problems in both urban and rural areas. Several lakes have

experienced eutrophication because of the

discharge

of un-

treated sewage and industrial waste. In Bangladesh, degrada-

tion of water and soil resources is widespread, and flood

conditions result in the spread of polluted water across areas

used for fishing and rice cultivation. Heavy use of pesticides

is also a concern there.

In the Philippines, air and soil pollution poses increas-

ing health risks, especially in urban areas. Industrial and

toxic waste disposals have severely polluted 38 river systems.

Widespread poverty and political instability has exac-

erbated Haiti’s environmental problems. Haiti, the poorest

1394

country in the Western Hemisphere, suffers from deforesta-

tion, land degradation, and water pollution. While the coun-

try has plentiful

groundwater

, less than 40% of the popula-

tion has access to safe drinking water.

As 117 world leaders and their representatives met at

the

United Nations Earth Summit

in 1992, some of these

concerns were addressed as poorer Third World countries

sought the help of richer industrialized nations to preserve

the

environment

. Almost always, environmental cleanup

in the Third World is an economic issue, and the countries

cannot afford to spend more on it.

Another issue affecting Third World pollution control

is the role of transnational corporations (TNCs) in global

environmental problems. A Third World Network econo-

mist cited TNCs for their responsibility for water and air

pollution, toxic wastes, hazardous

chemicals

and unsafe

working conditions in Third World countries. None of the

Earth Summit documents, however, regulated transnational

corporations, and the United Nations has closed its Center

for Transnational Corporations, which had been monitoring

TNC activities in the Third World.

There is a growing environment awareness in Third

World nations, and many are trying to correct the problems.

In Madras, India, sidewalk vendors sell rice wrapped in

banana leaf; the leaf can be thrown to the ground and is

consumed by one of the free-roaming cows on Madras’

streets. In Bombay, India, tea is sold in a brown clay cup

which can be crushed into the earth when empty. The Chi-

nese city of Shanghai produced all its own vegetables, fertil-

izes them with human waste, and exports a surplus.

Environmentalists worldwide are calling for a strength-

ened

United Nations Environment Programme

(UNEP)

to enact sanctions and keep polluters out of the Third World.

It could also enforce the “polluter pays” principle, eventually

affecting Western governments and companies that dump

on the Third World. Already, UNEP and the

World Bank

provide location advice and environmental

risk assessment

when the host country is not able to do so, and the World

Health Organization and the International Labor Organiza-

tion provide some guidance on occupational health and safety

to developing countries. See also Drinking-water supply; En-

vironmental policy; Environmental racism; Flooding; Haz-

ardous material; Industrial waste treatment; Marine pollu-

tion; Watershed management

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Barber, B. “Lessons from the Third World.” Omni (January 1992): 25.

Collins, C., and C. Darch. “Summit Sets a Rich Table, but Africa Gets

the Crumbs.” National Catholic Reporter 29 (July 3, 1992): 12.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Henry David Thoreau

Kumar, P. “Stop Dumping on the South.” World Press Review (June 1992):

12–13.

LaDou, J. “Deadly Migration: Hazardous Industries’ Flight to the Third

World.” Technology Review (July 1991): 47.

“Pollution and the Poor.” Economist 322 (February 15, 1992): 18–19.

Lee M. Thomas (1944 – )

American former Environmental Protection Agency admin-

istrator

If the 1960s and 1970s have become known as decades of

growing concern about environmental causes, the 1980s will

probably be remembered as a decade of stagnation and retreat

on many environmental issues. Presidents Ronald Reagan

and George Bush held very different beliefs about many

environmental problems than did their immediate predeces-

sors, both Democrat and Republican. Reagan and Bush both

argued that environmental concerns had resulted in costly

overregulation that acted as a brake on economic develop-

ment and contributed to the expansion of government bu-

reaucracy.

One of the key offices through which these policies

were implemented was the

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA). In 1985, President Reagan nominated Lee

M. Thomas to be Administrator of that agency. Thomas

had a long record of public service before his selection for

this position. Little of his service had anything to do with

environmental issues, however. Thomas began his political

career as a member of the Town Council in his hometown

of Ridgeway, South Carolina. He then moved on to a series

of posts in the South Carolina state government.

The first of these positions was as executive director

of the State Office of Criminal Justice Programs, a post he

assumed in 1972. In that office, Thomas was responsible

for developing criminal justice plans for the state and for

administering funds from the Law Enforcement Assistance

Administration.

Thomas left this office in 1977 and spent two years

working as an independent consultant in criminal justice.

Then, in 1979, he returned to state government as director

of Public Safety Programs for the state of South Carolina.

In addition to his responsibilities in public safety, Thomas

served as chairman of the Governor’s Task Force on Emer-

gency Response Capabilities in Support of Fixed Nuclear

Facilities. The purpose of the task force was to assess the

role of various state agencies and local governments in deal-

ing with emergencies at nuclear installations in the state.

Thomas’s first federal appointment came in 1981,

when he was appointed executive deputy director and associ-

ate director for State and Local Programs and Support of

the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). His

responsibilities covered a number of domestic programs, in-

1395

cluding Disaster Relief,

Floodplain

Management,

Earth-

quake

Hazard Reduction, and Radiological Emergency

Preparedness. While working at FEMA, Thomas also served

as chairman of the U.S./Mexican Working Group on Hy-

drological Phenomena and Geological Phenomena.

In 1983, President Reagan appointed Thomas assis-

tant administrator for

Solid Waste

and Emergency Re-

sponse of the EPA. In this position, Thomas was responsible

for two of the largest and most important of EPA programs,

the

Comprehensive Environmental Response Compen-

sation and Liability Act

(Superfund) and the

Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act

. Two years later, Thomas

was confirmed by the Senate as administrator of the EPA,

a position he held until 1989, when he became the Chairman

and Chief Executive Officer for Law Companies Environ-

mental Group Inc. Thomas then was employed as the Senior

Vice President, Environmental and Government Affairs for

the Georgia-Pacific Corporation. He currently is the Presi-

dent of Building Products and Distribution.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Thomas, Lee M. “The Business Community and the Environment: An

Important Partnership.” Business Horizons (March–April 1992): 21–24.

———. “Trends Affecting Corporate Environmental Policy: The Real

Estate Perspective.” Site Selection and Industrial Development 35 (October

1990): 1(1183)–3(1185).

Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862)

American writer and natural philosopher

Thoreau was a member of the group of radical Transcenden-

talists who lived in New England, especially Concord, Mas-

sachusetts, around the mid-nineteenth century. He is known

worldwide for two written works, both still widely read and

influential today: Walden, a book, and a tract entitled “Civil

Disobedience.” All of his works are still in print, but most

noteworthy is his 14-volume Journal, which some critics

think contains his best writing. Contemporary readers inter-

ested in

conservation

,

environmentalism

,

ecology

, natu-

ral history, the human

species

, or philosophy can gain great

understanding and wisdom from reading Thoreau.

Today, Thoreau would be considered not only a phi-

losopher, a humanist, and a writer, but also an ecologist

(though that word was not coined until after his death). His

status as a writer, naturalist, and conservationist has been

secure for decades; in conservation circles, he is recognized

as what Backpacker magazine calls one of the “elders of the

tribe.”

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Henry David Thoreau

Trying to trace any idea through Thoreau’s work is a

complicated task, and that is true of his ecology as well. One

straightforward example of Thoreau’s sophistication as an

ecologist is his essay on “The

Succession

of Forest Trees.”

Thoreau found the same unity in

nature

that present-day

ecologists study, and he often commented on it: “The birds

with their plumage and their notes are in harmony with

the flowers.” Only humans, he felt, find such connections

difficult: “Nature has no human inhabitants who appreciate

her.” Thoreau did appreciate his surroundings, both natural

and human, and studied them with a scientist’s eye. The

linkages he made showed an awareness of

niche

theory,

hierarchical connections, and trophic structure: “The perch

swallows the grub-worm, the pickerel swallows the perch,

and the fisherman swallows the pickerel; and so all the chinks

in the scale of being are filled.”

Much of Thoreau’s philosophy was concerned with

human ecology

, as he was perhaps most interested in how

human beings relate to the world around them. Often char-

acterized as a misanthrope, he should instead be recognized

for how deeply he cared about people and about how they

related to each other and to the natural world. As Walter

Harding notes, Thoreau believed that humans “Antaeus-

like, derived [their] strength from contact with nature.”

When Thoreau insists, as he does, for example, in his journal,

that “I assert no independence,” he is claiming relationship,

not only to “summer and winter...life and death,” but also

to “village life and commercial routine.” He flatly asserts

that “we belong to the community.” Present-day humans

could not more urgently ask the questions he asked: “Shall

I not have intelligence with the earth? Am I not partly leaves

and vegetable mold myself?”

The essence of Thoreau’s message to present-day citi-

zens of the United States can be found in his dictum in

Walden to “simplify, simplify.” That is a straightforward

message, but one he elaborates and repeats over and over

again. It is a message that many critics of today’s materialism

believe American citizens need to hear over and over again.

Right after those two words in his chapter on “What I Lived

For” is a directive on how to achieve simplicity. “Instead of

three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of

a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in propor-

tion,” he asserts. The message is repeated in different ways,

making a major theme, especially in Walden, but also in his

other writings: “A man is rich in proportion to the number

of things he can afford to let alone.” Thoreau’s preference

for simplicity is clear in the fact that he had only three chairs

in his house: “one for solitude, two for friendship, three for

society.” Thoreau is often quoted as stating “I would rather

sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself than be crowded

on a velvet cushion.”

1396

Hundreds of writers have joined Thoreau in censuring

the materialist root of current environmental problems, but

reading Thoreau may still be the best literary antidote to

that materialism. Consider the stressed commuter/city

worker who does not realize that the “cost of a thing is the

amount of...life which is required to be exchanged for it,

immediately or in the long run.” In the pursuit of fashion,

ponder his admonition to “beware of all enterprises that

require new clothes.”

Thoreau firmly believed that the rich are the most

impoverished: “Give me the poverty that enjoys true wealth.”

The enterprises he thought important were intangible, like

being present when the sun rose, or, instead of spending

money, spending hours observing a heron on a pond. Work-

ing for “treasures that moth and rust will corrupt and thieves

break through and steal...is a fool’s life.” As Thoreau noted,

too many of us make ourselves sick so that we “may lay up

something against a sick day.” To him, most of the luxuries,

and many of the so-called comforts of life, are not only

dispensable, “but positive hindrances to the elevation of man-

kind.” For most possessions, Thoreau’s forthright answer

was “it costs more than it comes to.”

Thoreau was a humanist, an abolitionist, and a strong

believer in egalitarian social systems. One of his criticisms

of materialism was that, in the race for more and more

money and goods, “a few are riding, but the rest are run

over.” He recalled that, before the modern materialist state,

it was less unfair: “In the savage state every family owns a

shelter as good as the best.” Thoreau was anti-materialistic

and believed that the relentless pursuit of “things” divert

people from the real problems at hand, including destruction

of the

environment

: “Our inventions are wont to be pretty

toys, which distract our attention from serious things.” In

this same vein, he claimed that “the greater part of what my

neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad.”

In modern life, stress is a major contributor to illness

and death. And, much of that stress is generated by the

constant acquisitive quest for more and more material goods.

Thoreau asks “why should we be in such desperate haste to

succeed and in such desperate enterprises?” He notes that

“from the desperate city you go into the desperate country”

with the result that “the mass of men lead lives of silent

desperation.” This passage was written in the nineteenth

century, but still echoes through the twenty first.

Simplification of lifestyle is now widely taught as a

practical antidote to the environmental and personal conse-

quences of the materialist cultures of the urban/industrial

twentieth century. And that kind of simplification is central

to Thoreau’s thought. But readers must remember that Tho-

reau was unmarried, childless, and often dependent on

friends and family for room and board. Thoreau lived on

and enjoyed the land around Walden Pond, for example,