Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sudbury, Ontario

The area around Sudbury, Ontario, was deforested by emissions from nickel and copper smelting. (Photograph

by A. J. Copley. Visuals Unlimited. Reproduced by permission.)

that exists without disturbance? Is fire a disturbance or a

maintenance factor? Even if a very old forest community is

considered, on a time scale of thousands of years, it may be

difficult to determine whether what is observed today is

really a permanent climax community or just a very long-

standing seral stage. Despite these questions, the concept

of an ultimate climax community is central to the idea of

succession.

Usually climax communities are considered more di-

verse than intermediate communities. Because climax com-

munities can remain stable for a long time, species can diver-

sify and develop specialized niches. This specialization can

lead to the coexistence of a great number of species, as is

the case in tropical rain forests, where thousands of species

may share just a few acres of forest. In some cases, however,

intermediate seral stages actually have greater diversity be-

cause they contain elements of multiple communities at once.

See also Biodiversity; Biological fertility; Ecological produc-

tivity; Growth limiting factors; Introduced species; Restora-

tion ecology

[Linda Rehkopf]

1357

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brown, J. H., and A. C. Gibson. Biogeography. St. Louis: Mosby, 1983.

Ricklefs, R. E. Ecology. 3rd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co., 1990.

Sudbury, Ontario

The town of Sudbury, Ontario, has been the site of a large

metal mining and processing industry since the latter part

of the nineteenth century. The principal metals that have

been sought from the Sudbury mines are

nickel

and

copper

.

Because of Sudbury’s long history of mining and processing,

it has sustained significant ecological damage and has pro-

vided scientists and environmentalists with a clear case study

of the results.

Mining and processing companies headquartered at

Sudbury began by using a processing technique that oxidized

sulfide ores using roast beds, or heaps of ore piled upon

wood. The heaps were ignited and left to smolder for several

months, after which cooled metal concentrate was collected

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sulfate particles

and shipped to a refinery for processing into pure metals.

The side effect of roast beds was the intense, ground-level

plumes of

sulfur dioxide

and metals, especially nickel and

copper, they produced. The

smoke

devastated local ecosys-

tems through direct phytotoxocity and by causing

acidifica-

tion

of

soil

and water. After the vegetative cover was killed,

soils eroded from slopes and exposed naked granitic-gneissic

bedrock, which became pitted and blackened from reaction

with the roast-bed plumes.

After 1928, the use of roast beds was outlawed, and

three smelters with

tall stacks

were constructed. These

emitted pollutants higher into the

atmosphere

, but some

local vegetation damage was still caused, lakes were acidified,

and toxic contaminants were spread over an increasingly

larger area.

Over the decades, well-defined patterns of ecological

damage developed around the Sudbury smelters. The most

devastated sites occurred closest to the sources of

emission

.

They had large concentrations of nickel, copper, and other

metals, were very acidic with resulting toxicity from soluble

aluminum

ions, and were frequently subjected to toxic fumi-

gations by sulfur dioxide. Such sites had very little or no

plant cover, and the few

species

that were present were

usually physiologically tolerant ecotypes of a few widespread

species.

Ecological damage and environmental contamination

lessened with increasing distance from the

point source

of

emissions. Obvious damage to terrestrial ecosystems was

difficult to detect beyond 10–12 mi (15–20 km), but contam-

ination with nickel and copper could be observed much

farther away.

Oligotrophic

lakes with clear water, low fertil-

ity, and little buffering capacity, however, were acidified by

the

dry deposition

of sulfur dioxide at least 25–31 mi (40–

50 km) from Sudbury.

In 1972, a very tall, 1,247-ft (380-m) “superstack”

was constructed at the largest of the Sudbury smelters. The

superstack resulted in an even greater dispersion of

smelter

emissions. This, combined with closing of another smelter,

and reduction of emissions by

flue gas

desulfurization and

the processing of lower-sulfur ores, resulted in a substantial

improvement of local

air quality

. Consequently, a notable

increase in the cover and species richness of plant cover close

to the Sudbury smelters has occurred, a process that has been

actively encouraged by revegetation activities along roadways

and other amenity areas where soil remained. Lakes close

to the superstack and the closed smelter have also become

less acidic, and their biota has responded accordingly. There

is controversy, however, about the contributions that the

still large emissions of sulfur dioxide may be making towards

the regional

acid rain

problem. It is possible that height of

the superstack will be decreased to reduce the longer-range

1358

transport of emitted sulfur dioxide. See also Air pollution;

Contaminated soil; Water pollution

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Freedman, B. Environmental Ecology. San Diego: Academic Press, 1989.

Nriagu, J., ed. Environmental Impacts of Smelters. New York: J. Wiley, 1984.

Sulfate particles

Sulfate particles are sub-micron sized, sulfur-containing air-

borne particles. Most sulfate is a secondary pollutant, formed

by the oxidation in the

atmosphere

of

sulfur dioxide

gas.

Sulfur dioxide is emitted largely in fossil fuel

combustion

,

particularly from

power plants

burning

coal

. A small frac-

tion (generally well under 10%) of sulfur is emitted as primary

sulfate at the combustion source. The use of coal-cleaning,

scrubbers

, and low sulfur coal have reduced sulfur dioxide

emissions in the United States, and thus airborne sulfate

concentrations have decreased.

In the atmosphere, sulfur dioxide (SO

2

) emissions are

slowly transformed to sulfate (SO

4

) at a rate of 0.1–5%

per hour, with the rate increased by higher temperatures,

sunshine, and the presence of oxidants. Further reactions

with water vapor may produce sulfuric

acid

(H

2

SO

4

), a

corrosive acid which is injurious to ecosystems and humans,

and also ammonium sulfate (NH

4

)

2

SO

4

, which is particu-

larly effective at impairing

visibility

. The atmospheric

resi-

dence time

for sulfate particles is long, 2–10 days, which

permits transport on a regional or continental scale across

hundreds or thousands of miles. Because sulfate particles are

relatively soluble, precipitation effectively washes them out,

resulting in

acid rain

. Of the various sizes of aerosols, sulfate

particles are in the accumulation mode, and typically there

might be about 10,000 particles per 0.06 in

3

(1 cm

3

)inan

urban area.

In addition to problems of acid rain and visibility

degradation, sulfate particles can cause a number of health

problems. Community epidemiological studies report associ-

ations of annual and multi-year average concentrations of

PM

10

(particulates), PM

2.5

(fine

particulate

), and sulfates

with health effects that include premature

mortality

, in-

creased respiratory symptoms and illness (e.g.,

bronchitis

and cough in children), and reduced lung function. The

risks associated with long-term exposures, although highly

uncertain, appear to be larger than those associated with

short-term exposures. Other analyses have shown statistically

significant associations between sulfate and other particulate

air pollutants with total and cardiopulmonary mortality. Ad-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

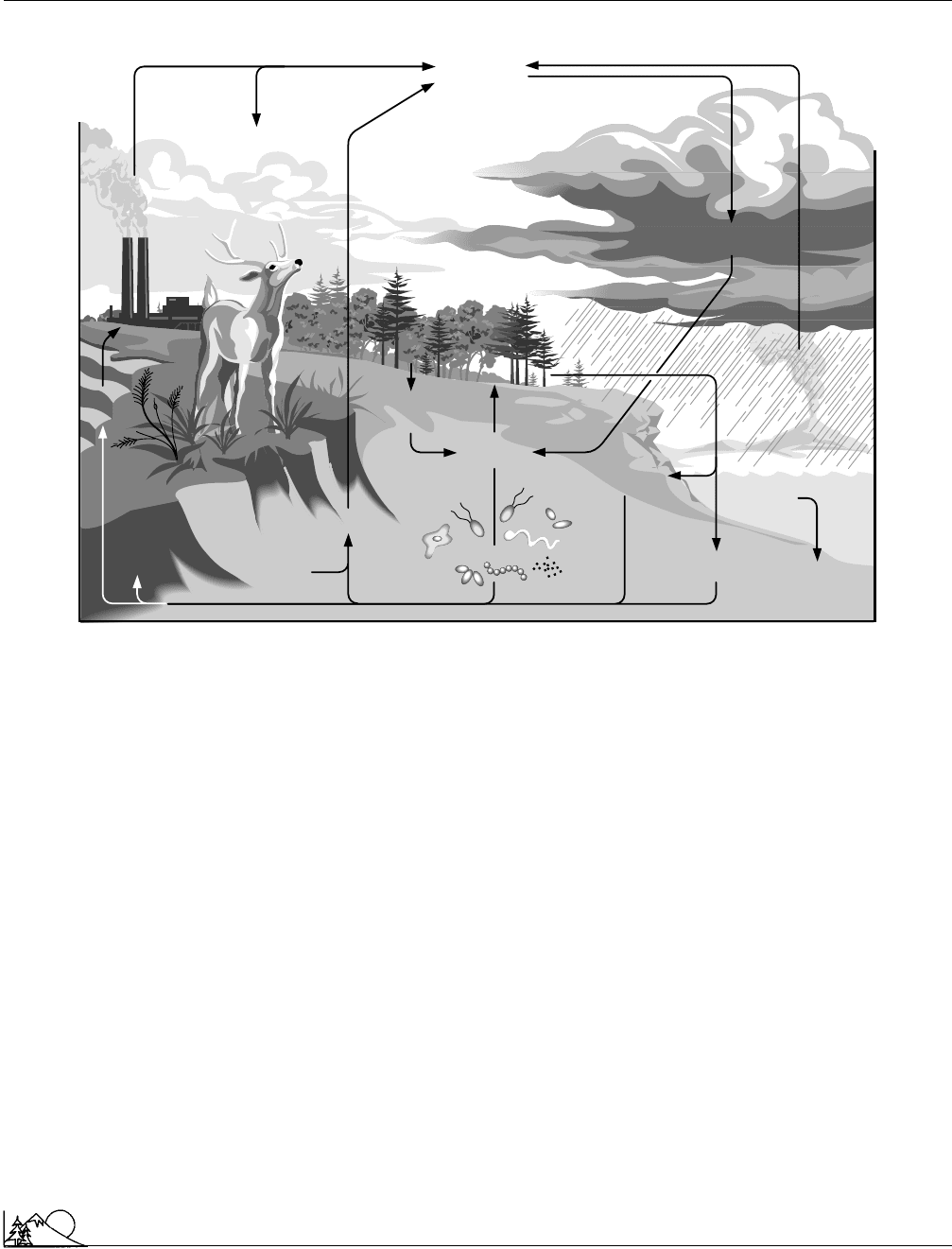

Sulfur cycle

Sulfates

in atmosphere

Sulfur dioxide (SO

2

)

from combustion of fossil

fuels and sulfide metal ores

Sulfur in

fossil fuels

M

i

n

i

n

g

Iron sulfides

in deep

soils and

sediments

Decomposition

and other

processing

Uptake

by plants

Sulfates in soil

(SO

4

2

⫺

)

Sedimentation

sulfates and sulfides

Organic

deposition

Sulfates in water

(SO

4

2

⫺

)

Deposition

of sulfides to

sediment

Acidic precipitation

(rain, snow)

Dry deposition

of sulfate and

sulfur dioxide

(SO

2

)

Plants

Animals

Sulfur dioxide (SO

2

)

and sulfate

from volcanoes

and hot springs

Reduced sulfur (H

2

S)

Microorganisms

The sulfur cycle. (Illustration by Hans & Cassidy.)

ditionally, animal studies suggest that concentrations ap-

proaching ambient levels of ammonium sulfate and nitrate

can cause morphometric changes that could lead to a decrease

in compliance or a “stiffening” of the lung.

Because of the long time and distance scales required

for transformation, and because sulfate particles are small,

which allows them to remain airborne for several days, sulfate

concentrations tend to be uniformly distributed across broad

regions. In the eastern United States, sulfate particles consti-

tute half or more of fine fraction particle concentrations (also

called PM

2.5

. Thus, much of the sulfate in an urban area or

airshed

arises from distant or “regional” sources. If at high

levels, this “background” component can pose a dilemma for

air quality

management, since

emission

reductions from

local sources do not control the problem. Instead, trans-

boundary agreements such as the Canada-United States Air

Quality Agreement, which was signed March 13, 1991, have

been used to monitor and control emissions from distant

sources that cause most of the emissions.

Governmental regulations in the United States do not

directly address sulfate; however, the

National Ambient Air

Quality Standards

do set limits on particulate concentra-

1359

tions (PM

10

), and regulations on fine particulate (PM

2.5

)

have been proposed. In addition to these ambient standards,

regulations limit emissions of sulfur dioxide at sources (in the

New Source Performance Standards), and the degradation of

existing air quality levels (Prevention of Significant Deterio-

ration). In Europe, deposition of acidic compounds, largely

from atmospheric sulfate, is controlled by setting critical

loads that depend on the capacity of a region to withstand

acid inputs without lake and

soil acidification

.

[Stuart Batterman]

Sulfur cycle

The series of chemical reactions by which sulfur moves

through the earth’s

atmosphere

, hydrosphere, lithosphere,

and

biosphere

. Sulfur enters the atmosphere naturally from

volcanoes and hot springs and through the

anaerobic

decay

of organisms. It exists in the atmosphere primarily as

hydro-

gen

sulfide and

sulfur dioxide

. After conversion to sulfates

in the air, sulfur is carried to the earth’s surface by precipita-

tion. There it is incorporated into plants and animals who

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sulfur dioxide

return sulfur to the earth’s crust when they die. Through

their use of

fossil fuels

, humans have a large effect on

the sulfur cycle, approximately tripling the amount of the

element returned to the atmosphere.

Sulfur dioxide

Along with sulfur trioxide, one of the two common oxides

of sulfur existing in the

atmosphere

. Sulfur dioxide is pro-

duced naturally in the atmosphere by the oxidation of

hydro-

gen

sulfide, a gas released from volcanoes and hot springs.

About 22 million tons (20 million metric tons) of sulfur

dioxide is released annually into the atmosphere by human

activities, primarily during the

combustion

of

fossil fuels

.

The amount of

anthropogenic

sulfur dioxide is roughly

equal to that formed naturally from hydrogen sulfide. Sulfur

dioxide reacts with water in clouds to form

acid rain

, causes

damage in plants, and is responsible for a variety of respira-

tory problems in humans.

Superconductivity

In 1911, Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh-Onnes discov-

ered that some materials, when cooled to very low tempera-

tures—within a few degrees of absolute zero—become super-

conductive, losing all

resistance

to the flow of electric

current. Potentially, that discovery had enormous practical

significance because a large fraction of the electrical energy

that flows through any appliance is wasted in overcoming

resistance. Kamerlingh-Onnes’s discovery remained a labo-

ratory curiosity for over 70 years, however, because the low

temperatures needed to produce superconductivity are diffi-

cult to achieve. Then, in 1985, scientists discovered a new

class of compounds that become superconductive at much

higher temperatures (about -74°F [-170°C]). The use of

such materials in the manufacture of electrical equipment

promises to greatly increase the efficiency of such equipment.

Superfund

see

Comprehensive Environmental

Response, Compensation, and Liability Act;

Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization

Act (1986)

Superfund Amendments and

Reauthorization Act (1986)

Congress initially authorized

Comprehensive Environ-

mental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act

1360

(CERCLA) legislation in 1980 to clean up abandoned dump

sites in the United States that contained

hazardous waste

.

The activities mandated under CERCLA were to be admin-

istered by the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA).

The program was reauthorized in 1986 by the Superfund

Amendment and Reauthorization Act (SARA) and more

commonly referred to as simply the Superfund. Several pro-

visions of CERCLA were changed or clarified.

Superfund sites identified in the original legislation

were virtually ignored during the early 1980s. Several key

EPA officials resigned after they were charged with misman-

aging the monies allocated by the original legislation. The

EPA attempted to speed cleanup of contaminated sites, but

progress was still too slow for critics, some members of

Congress and many individual citizens. When the program

expired in September 1985, the cleanup activities at more

than 200 sites were delayed for lack of funds. Concern about

hazardous waste sites continued. This pressure on Congress

was sufficient to facilitate reauthorization of CERCLA.

The Superfund was originally financed by a tax on

receipt of hazardous waste, and by a tax on domestic refined

or imported crude oil and

chemicals

. The SARA reauthori-

zation increased funding from $1.6 billion to $8.5 billion

over five years. It also authorized the use of contributions

from potentially responsible parties (persons who had created

the environmental hazards or who currently owned the land

on which former dump sited were located). SARA declined

to place the full financial burden of cleanup on oil and

chemical companies. As of 2002, funding is obtained from

a broad-based combination of business and public contribu-

tions.

SARA emphasizes the importance of remedial actions,

specifically those that reduce the volume, toxicity, or mobility

of hazardous substances, pollutants and contaminants. Tar-

gets for long-term remedial actions are listed on the

Na-

tional Priorities List

. This listing is revised each year.

As of 2002, more than 1,300 sites around the nation

have been placed on the National Priorities List. These sites

are considered to be the worst in the country. A total of

40,000 uncontrolled waste sites have been reported to U.S.

federal agencies. As of June 2002, work has been completed

on a total of 812 sites in the National Priorities List. Factors

used to rank the severity of reported sites include the type,

quantity, and toxicity of the substance(s) found at the site,

as well as the number of people likely to be exposed, the

pathways of exposure, and the vulnerability of the

ground-

water

supply at the site. If a site poses immediate threats

such as the risk of fire or explosion, the EPA may initiate

short-term actions to remove those threats before actual

cleanup begins.

Critics charge that the number of hazardous waste

sites nationwide is still underreported. Many states have

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Surface mining

developed their own programs to supplement the federal

Superfund.

Under SARA guidelines, the

Agency for Toxic Sub-

stances and Disease Registry

performs health assessments

at Superfund sites. This program, administered by the

Cen-

ters for Disease Control and Prevention

, also lists hazard-

ous substances found on sites, prepares toxicological profiles,

identifies gaps in research on health effects, and publishes

findings. See also Chemical spills; Emergency Planning and

Community Right-to-Know Act; Hazardous material; Haz-

ardous Substances Act; Toxic substance; Toxic Substances

Control Act; Toxic use reduction legislation

[L. Fleming Fallon Jr., M.D., Dr.P.H.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Church, T. W. Cleaning Up the Mess: Implementation Strategies in the

Superfund Program. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute, 1993.

Fogelman, V. M. Hazardous Waste Cleanup, Liability, and Litigation: A

Comprehensive Guide to Superfund Law. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publish-

ing Group, 1992.

Hutchins, D. C., and R. J. Moriarty. Walking By Day. Solon, OH: CPR

Prompt Corp, 1998.

Meyers, R. A., and D. K. Dittrick. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Environmental

Pollution and Cleanup. New York: Wiley, 1999.

Pearson, Eric. Environmental and Natural Resources Law. Albany, NY:

Matthew Bender & Company, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Au, W. W., and H. Falk. “Superfund Research Program—Accomplish-

ments and Future Opportunities.” International Journal of Hygiene and

Environmental Health (2002): 165–168.

Lindell, M. K., and R. W. Perry. “Community Innovation in Hazardous

Materials Management: Progress in Implementing SARA Title III in the

United States.” Journal of Hazardous Materials (2001): 169–194.

Wentsel, R. S., B. Blaney, L. Kowalski, D. A. Bennett, P. Grevatt, and

S. Frey. “Future Directions for EPA Superfund Research.” International

Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health (2002): 161–163.

O

THER

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Superfund Reauthoriza-

tion. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/superfnd.html>.

Superfund Basic Research Program. [cited July 2002]. <http://benson.niehs.-

nih.gov/sbrp>.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. <http://www.epa.gov/superfund/

> and <http://www.epa.gov/superfund/sites/> and <http://es.epa.gov/oeca/

spfund/> and <http://www.epa.gov/superfund/sites/npl/npl.htm> and

<http://www.epa.gov/superfund/sites/npl/info.htm>.

Surface mining

Surface mining techniques are used when a vein of

coal

or

other substance lies so close to the surface that it can be

mined with bulldozers, power shovels, and trucks instead of

using deep shaft mines, explosive devices, or

coal gasifica-

tion

techniques. Surface mining is especially useful when

1361

the rock contains so little of the ore being mined that conven-

tional techniques, such as tunneling along veins, cannot be

used. Surface mining removes the earth and rock that lies

above the coal or mineral seam and places the

overburden

off to one side as

spoil

. The exposed ore is removed and

preliminary processing is done on site or the ore is taken by

truck to processing plants. After the mining operations are

complete, the surface can be recontoured, restored, and re-

claimed.

Surface mining already accounts for over 60% of the

world’s total mineral production, and the percentage is in-

creasing substantially. Many factors contribute to the popu-

larity of surface mining. The lead time for developing a

surface mine averages four years, as opposed to eight years

for underground mines. Productivity of workers at surface

mines is three times greater than that of workers in under-

ground mining operations. The capital cost for surface mine

development is between 20 and 40 dollars per annual ton

of salable coal, and the start-up expenses for underground

mining operations are at least twice that, averaging around

80 dollars per annual ton.

The preliminary stages of mine development involve

gathering detailed information about the potential mining

site. Trenching and core drilling provide information on the

coal seam as well as the overburden and the general geological

composition of the site. Analysis of the drill core from the

overburden is an important step in preventing environmental

hazards. For example, when the shale between coal seams

and the underlying strata is disturbed by mining, it can

produce

acid

. If this instability in the strata is detected by

analysis of the drill cores, acid

runoff

can be avoided by

appropriate mine design. The data obtained from the prelim-

inary drilling is plotted on topographic maps so that the

relationship between seams of ore and the overlying terrain

are clearly visible.

After test results and all other relevant data have been

obtained, the information is entered into a computer system

for analysis. Various mine designs and mining sequences are

tested by the computer models and evaluated according to

technical and economic criteria in order to determine the

optimal mine design. Satellite imagery and aerial photo-

graphs are usually taken during the exploratory stages. These

photographs serve as an excellent visual record of the actual

environmental conditions prior to the mining operation, and

they are frequently utilized during the

reclamation

process.

There are several types of surface mining, and these

include area mining, contour mining, auger mining, and

open-pit mining. Area mining is used predominantly in the

Midwest and western mountain states, where coal seams lie

horizontally beneath the surface. Operations begin near the

coal outcrop—the point where the ore lies closest to the

surface. Large stripping shovels or draglines dig long parallel

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Surface mining

trenches; this removes the overburden, leaving the ore ex-

posed. The overburden excavated from the trench is thrown

into the previous trench, from which coal has already been

extracted. The process is similar to a farmer plowing a field

in furrows. Because of the steep slopes and rugged terrain

frequently encountered in area mining operations, the ore

is usually recovered by small equipment such as front end

bucket loaders, bulldozers, and trucks.

Area mining is also practiced in Appalachia, where

many of the coal seams lie under mountains or foothills. This

type of area mining is commonly known as mountaintop

removal. The mountains mined using this technique gener-

ally have long ridges with underlying deposits. A cut is made

parallel to the ridge, and subsequent cuts are made parallel

to the first; this results in the entire top of the mountain

being leveled off and flattened out. When these areas are

reclaimed, the most frequent designated uses are grazing

lands or development sites.

Contour mining is used primarily at the point where

the seam lies closest to the surface, on steep inclines such

as in the Appalachian mountains. In these areas, coal usually

lies in flat continuous beds, and the excavation continues

along the side of the mountain. This produces a long, narrow

trench, with highwall extending along the trench—the con-

tour line for horizontal coal seams. Recent federal regulations

have outlawed many contour mining practices, such as leav-

ing exposed highwall and spoil on the mountainside.

The auger process is used primarily in salvage opera-

tions. When it is no longer economically profitable to remove

the overburden in the highwall, augering techniques are

utilized to recover additional tonnage. The auger extracts

coal by boring underneath the final highwall. Currently,

auger mining only accounts for 4% of surface-mined coal

production in the United States.

Open-pit mining is used primarily in western states,

where coal seams are at least 100 ft (30 m) thick. The thin

overburden is removed and taken away from the site by

truck, leaving the exposed coal seam. This type of mine

operation is very similar to rock quarry operations.

The equipment used in surface mining ranges from

bulldozers, front-end bucket loaders, scrapers, and trucks to

gigantic power shovels, bucket-wheel excavators, and drag-

lines. Over the past ten years, technological development

has concentrated on mechanization and development of

heavy-duty equipment. Due to economic factors, equipment

manufacturers have focused on improving performance of

existing equipment instead of developing new technologies.

Since the recession of the 1980s, bucket capacity and the

size of conventional machines have increased. Concentration

of production technology has created mining systems that

1362

incorporate mining equipment with continuous

transporta-

tion

systems and integrated computers into all aspects of

the industry.

Surface mining can have severe environmental effects.

The process removes all vegetation, destroying microflora

and

microorganisms

. The

soil

,

subsoil

, and strata are bro-

ken and removed.

Wildlife

is displaced,

air quality

suffers,

and surface changes occur due to oxidation and topographic

changes.

Hydrology

associated with surface mining has a major

effect on the

environment

. Removal of overburden may

change the

groundwater

in numerous ways, including

drainage

of water from the area, altering the direction of

aquifer

flow, and lowering the water tables. It also creates

channels that allow contaminated water to mingle with water

of other aquifers. Acid water runoff from the mining opera-

tions can contaminate the area and other water sources. In

addition to being highly acidic, the runoff from mining

operations also contains many other trace elements that ad-

versely affect the environment.

Federal regulations require that

topsoil

be redistrib-

uted after the mining is complete, but many people do not

consider this requirement sufficient. When soil is removed,

the soil structure breaks down and compacts, preventing

normal organic matter from getting into the soil. Microor-

ganisms are destroyed by the changes in the soil and the

lack of organic components. The rate of

erosion

in mining

areas is also greatly increased due to the lack of native vege-

tation.

The removal of vegetation and overburden at the min-

ing site displaces all wildlife, and a large portion of it may

be completely destroyed. Some forms of wildlife, such as

birds and game animals, may get out of the area safely, but

those that hibernate or burrow usually die as a result of the

mining. Ponds, streams, and swamps are routinely drained

before mining operations commence and all aquatic life in

the region is destroyed.

In addition to the short-term environmental effects,

surface mining also has long-term impact on the

flora

and

fauna

within the region of the mine. Salts,

heavy

metals

, acids, and other minerals exposed during removal

of overburden suppress growth rate and productivity. Due

to changes in soil composition, many native

species

of

plants are unable to adjust. The loss of vegetation means

a loss of feeding grounds, which in turn disrupts

migration

patterns. Displaced species encroach on neighboring eco-

systems, which may cause overpopulation and disruption

of adjacent habitats. See also Surface Mining Control and

Reclamation Act

[Debra Glidden]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Survivorship

An open-pit copper mine. (Photograph by Paul Logsdon. Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Chironis, N. “With Dozers Bigger Is Better.” Coal Age 91 (July 1986): 56.

Sanda, A. “Draglines Dominate Big Surface Mines.” Coal Age 96 (July

1991): 30.

Schmidt, B. “GAO to Interior: Get Tough on Mining.” American Metal

Market 96 (December 21, 1988): 2.

Singhal, R. K. “In Pit Crushing and Conveying Systems.” World Mining

Equipment 10 (January 1986): 24.

“Surface Mining Costs Decline in the Midwest.” Mining 91 (May 1986): 10.

Surface Mining Control and

Reclamation Act (1977)

This act set minimum federal standards for surface

coal

mining and

reclamation

of mining sites. The act requires

that: (1) mine operators demonstrate reclamation capability;

(2) previous uses must be restored and the land reshaped to

its original contour, with

topsoil

replacement and replant-

ing; (3) mining be prohibited on prime western agricultural

land, with farmers and ranchers holding veto power; (4) the

hydrologic

environment

must be protected, especially from

1363

acid drainage

; and (5) a $4.1 billion fund be established

to reclaim abandoned strip mines. States have enforcement

responsibility, but the

U.S. Department of the Interior

steps

in if they fail to act.

Surface-water quality

see

Water quality

Survivorship

The term “survivorship” describes the likelihood that an

organism will remain alive from one time period to the next.

For example, the survivorship of human males in a given

country to age 20 might be around 96.5%, while survivorship

to age 70 might be 55%.

Age-specific

mortality

can be illustrated in the form

of a survivorship curve that usually yields one of three patterns

of survivorship: mortality concentrated at the end of the

maximum life span; a constant

probability

of death for

every age group; or high early mortality followed by high

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Suspended solid

survival. Survivorship can also be depicted with a life table

showing the number of survivors from a given starting popu-

lation at specific intervals.

Suspended solid

Refers to a solid that is suspended in a liquid. Most treatment

facilities for both municipal and industrial wastewaters must

meet

effluent

standards for total suspended solids (TSS).

A typical TSS limit for a secondary

wastewater

treatment

plant is 20 mg/L. However, some industries may have per-

mits that allow them to

discharge

much more, for example,

500 mg/L. The test for TSS is commonly performed by

filtering a known amount of water through a pre-weighed

glass-fiber or 0.45 micron () porosity filter. The filter with

the solids is then dried in an oven (217°–221°F [103°–

105°C]) and weighed. The amount of dried solid matter on

the filter per amount of water originally filtered is expressed

in terms of mg/L. Solids which pass through the filter in

the filtrate are referred to as

dissolved solids

. Settleable

solids (i.e., those that settle in a standard test within 30

minutes) are a type of suspended solids, but not all suspended

solids are settleable solids.

Sustainable agriculture

Because of concerns over pesticides and

nitrates

in

ground-

water

,

soil erosion

,

pesticide

residues in food,

pest

resis-

tance to pesticides, and the rising costs of purchased inputs

needed for conventional agriculture, many farmers have be-

gun to adopt alternative practices with the goals of reducing

input costs, preserving the resource base, and protecting

human health. This is called sustainable agriculture.

Many of the components of sustainable agriculture are

derived from conventional agronomic practices and livestock

husbandry. Sustainable systems more deliberately integrate

and take advantage of naturally occurring beneficial interac-

tions. Sustainable systems emphasize management, biologi-

cal relationships such as those between the pest and predator,

and natural processes such as

nitrogen fixation

instead of

chemically intensive methods. The objective is to sustain

and enhance, rather than reduce and simplify, the biological

interactions on which production agriculture depends,

thereby reducing the harmful off-farm effects of production

practices.

Examples of practices and principles emphasized in

sustainable agriculture systems include:

O

Crop rotations that mitigate weed, disease, insect, and

other pest problems; increase available soil

nitrogen

and

reduce the need for purchased fertilizers; and, in conjunc-

1364

tion with

conservation tillage

practices, reduce soil

erosion.

O

Integrated pest management

(IPM) that reduces the

need for pesticides by crop rotations, scouting weather

monitoring, use of resistant cultivars, timing of planting,

and biological pest controls.

O

Soil and

water conservation

tillage practices that increase

the amount of crop residues on the soil surface and reduce

the number of times farmers have to till the soil.

O

Animal production systems that emphasize disease preven-

tion through health maintenance, thereby reducing the

need for antibiotics.

Many farmers and people of rural communities are

starting to explore the possibilities of systems of sustainable

agriculture. The term “systems” is used because there is no

one single way to farm sustainably. The possible ways are

as numerous as farmers and potential farmers.

The first aspect of sustainable agriculture is the under-

standing that a respect for life, in its various forms, is not

only desirable but necessary to human survival. A second

aspect requires that the farming system not put life in jeop-

ardy, and that its methods not deplete the soil or the water

or place farmers in situations where they themselves are

depleted, either in numbers or in the quality of their lives.

Another aspect of sustainable agriculture recognizes

that farming families are an essential part of a sustainable

system. Farmers are the systems’ stewards, or caregivers. As

stewards, they know their land better than anyone else and

are equipped to shoulder the challenge of developing a sus-

tainable system on that land. In a sustainable system, farmers

ideally move toward less dependence on off-farm purchased

inputs and more toward natural or organic materials. This

is accomplished by gaining knowledge about the intricate

biological and economic workings of the farm. Lastly, sus-

tainable agricultural systems require the support of consum-

ers as well; they can give support, for example, by selectively

buying food raised in close proximity to a buyer’s local

market.

[Terence H. Cooper]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

National Research Council Board on Agriculture. Alternative Agriculture.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1989.

P

ERIODICALS

Thesing, C. “What Is Sustainable Agriculture?” The Land Stewardship

Letter 10 (1992): 13–14.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sustainable architecture

Sustainable architecture

Sustainable architecture refers to the practice of designing

buildings which create living environments that work to

minimize the human use of resources. This is reflected both

in a building’s construction materials and methods and in

its use of resources, such as in heating, cooling, power, water,

and

wastewater

treatment.

The operating concept is that structures so designed

“sustain” their users by providing healthy environments, im-

proving the quality of life, and avoiding the production of

waste, to preserve the long-term survivability of the human

species

.

Hunter and

Amory Lovins

of the

Rocky Mountain

Institute

say the purpose of sustainable architecture is to

“meet the needs of the present without compromising the

ability of

future generations

to meet their own needs.”

The term, however, is a broad one, and is used to

describe a wide variety of aspects of building design and use.

For some, it applies to designing buildings that produce as

much energy as they consume. Another interpretation calls

for a consciousness of the spiritual significance of a building’s

design, construction, and siting. Also, some maintain that

the buildings must foster the spiritual and physical well-

being of their users.

One school of thought maintains that, in its highest

form, sustainable architecture replicates a stable

ecosystem

.

According to noted ecological engineer David Del Porto, a

building designed for sustainability is a balanced system

where there are no wastes, because the outputs of one process

become the inputs of another. Energy, matter, and informa-

tion are cascaded through connected processes in cyclical

pathways, which by virtue of their efficiency and interdepen-

dence yield the matrix elements of environmental and eco-

nomic security, high quality of life, and no waste. The con-

stant input of the sun replenishes any energy lost in the

process.

Sustainability, as it relates to resources, became a

widely used term with

Lester Brown’s

book, Building a

Sustainable Society, and with the publishing of the Interna-

tional Union on the Conservation of Nature’s “World Con-

servation Strategy” in 1980.

Sustainability then came to describe a state whereby

natural renewable resources are used in a manner that does

not eliminate or degrade them or otherwise diminish their

renewable usefulness for future generations, while main-

taining effectively constant or non-declining stocks of

natu-

ral resources

such as

soil

,

groundwater

, and

biomass

(

World Resources Institute

).

Before “sustainable architecture,” the term “solar archi-

tecture” was used to express the architectural approach to

reducing the consumption of natural resources and fuels by

1365

capturing

solar energy

. This evolved into the current and

broader concept of sustainable architecture, which expands

the scope of issues involved to include water use,

climate

control, food production, air purification,

solid waste recla-

mation

, wastewater treatment, and overall

energy effi-

ciency

. It also encompasses building materials, emphasizing

the use of local materials, renewable resources and recycled

materials, and the mental and physical comfort of the build-

ing’s inhabitants. In addition, sustainable architecture calls

for the siting and design of a building to harmonize with

its surroundings.

The United Nations lists the following five principles

of sustainable architecture:

O

Healthful interior environment. All possible measures are

to be taken to ensure that materials and building systems

do not emit toxic substances and gasses into the interior

atmosphere

. Additional measures are to be taken to clean

and revitalize interior air with

filtration

and plantings.

O

Resource efficiency. All possible measures are to be taken to

ensure that the building’s use of energy and other resources

is minimal. Cooling, heating, and lighting systems are to

use methods and products that conserve or eliminate energy

use. Water use and the production of wastewater are mini-

mized.

O

Ecologically benign materials. All possible measures are to be

taken to use building materials and products that minimize

destruction of the global

environment

. Wood is to be

selected based on non-destructive forestry practices. Other

materials and products are to be considered based on the

toxic waste output of production. Many practitioners cite

an additional criterion: that the long-term environmental

and societal costs to produce the building’s materials must

be considered and prove in keeping with sustainability

goals.

O

Environmental form. All possible measures are to be taken

to relate the form and plan of the design to the site, the

region, and the climate. Measures are to be taken to “heal”

and augment the

ecology

of the site. Accommodations

are to be made for

recycling

and energy efficiency. Mea-

sures are to be taken to relate the form of building to

a harmonious relationship between the inhabitants and

nature

.

O

Good design. All possible measures are to be taken to achieve

an efficient, long-lasting, and elegant relationship of area

use, circulation, building form, mechanical systems, and

construction technology. Symbolic relationships with ap-

propriate history, the Earth, and spiritual principles are to

be searched for and expressed. Finished buildings shall be

well built, easy to use, and beautiful.

The NMB Bank headquarters in Amsterdam, the

Netherlands, is an example of sustainable architecture. Con-

structed in 1978, this approximately 150,000-ft

2

(45,500-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Sustainable biosphere

m

2

) complex is a meandering S-curve of 10 buildings, each

offering different orientations and views of gardens. Con-

structed of natural and low-polluting materials, the buildings

feature organic design lines, indoor and outdoor gardens,

passive solar elements, heat recovery, water features, and

natural lighting and ventilation. Built for an estimated 5%

more than a conventional office building, the NMB build-

ing’s operating costs are only 30% of those of a conventional

building. Another example is the Solar Living Center in

Hopland, California, which employs both passive and photo-

voltaic solar elements, as well as ecological wastewater sys-

tems. The rice straw bale and cement building is constructed

around a solar calendar.

Sustainable architecture as a movement

Some maintain that sustainability, as it relates to archi-

tecture, refers to a process and an attitude or viewpoint.

Sustainability is “a process of responsible consumption,

wherein waste is minimized, and buildings interact in bal-

anced ways with natural environments and cycles, balancing

the desires and activities of humankind within the integrity

and

carrying capacity

of nature, and achieving a stable,

long-term relationship within the limits of their local and

global environment.” (Rocky Mountain Institute.)

However, sustainable architecture does not necessarily

mean a reduction in material comfort. Sustainability repre-

sents a transition from a period of degradation of the natural

environment (as represented by the industrial revolution and

its associated unplanned and wasteful patterns of growth)

to a more humane and natural environment. It is doing more

with less.

Proponents of sustainable architecture occasionally de-

bate the broader applications of the term. Some say that

sustainable buildings should generate more energy over time

(in the form of power, etc.) than was required to construct,

fabricate their materials, operate, and maintain them. This

is also referred to as “regenerative architecture,” which John

Tillman Lyle sums up in his book, Regenerative Design for

Sustainable Development, as “living on the interest yielded

by natural resources rather than the capital.” Others simply

see it as an approach to making buildings less consumptive

of natural resources.

Spiritual aspects of sustainable architecture

A spiritual viewpoint is that sustainable architecture

is “stewardship,” a recognition and celebration of the human

environment as a vital part of the larger universe and of

humankind’s role as caretakers of the earth. Viewed in this

way, resources are regarded as sacred. Another perspective

is that the creation of a building in the likeness of a living

system is somewhat religious, as a divine entity creates a

living order.

Although the term communicates slightly different

meanings to various audiences, it nevertheless serves as a

1366

consciousness-raising focus for creating greater concern for

the built environment and its long-term viability. Rather

than representing a return to subsistence living, buildings

designed for sustainability aim to improve the quality and

standards of living. Sustainable architecture recognizes peo-

ple as temporary stewards of their environments, working

toward a respect for natural systems and a higher quality

of life.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Barnett, D., and W. Browning. A Primer on Sustainable Building. Colorado:

Rocky Mountain Institute, 1995.

Dimensions of Sustainable Development. Washington, DC: World Resources

Institute, 1990.

Lyle, J. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development. New York: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1994.

Nebel, B. J. Environmental Science: The Way the World Works. 3rd ed. New

York: Prentice Hall, 1990.

Orr, D. W. Ecological Literacy. New York: State University of New York

Press, 1992.

World Resources 1992–93: A Guide to the Global Environment. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1992.

O

THER

Kremers, J. “Sustainable Architecture.” Architronic December 1996 [cited

July 2002] <http://architronic.saed.kent.edu>.

Sustainable biosphere

The

biosphere

is the region of the earth that supports life;

it includes all land, water, and the thin layer of air above

the earth. A sustainable biosphere is one with the continuing

ability to support life.

Some scientists have suggested that the oceans and

atmosphere

in the biosphere adjust to ensure the continua-

tion of life—a theory known as the

Gaia hypothesis

. British

scientist

James Lovelock

first proposed it in the late 1970s.

He argued that in the last 4,500 years of the earth’s approxi-

mately five billion years of existence, humans have been

placing increasingly greater stress on the biosphere. He called

for a new awareness of the situation and insisted that changes

in human behavior were necessary to maintain a biosphere

capable of supporting life. Maintaining a sustainable bio-

sphere involves the integrated management of land, water,

and air.

The land management practices that many believe are

necessary for sustaining the biosphere require

conservation

and planting techniques that control

soil erosion

. These

techniques encourage farmers to use organic fertilizers in-

stead of synthesized ones. Recycled manure and composted

plant materials can be used to put nutrients back into the