Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Trail Smelter arbitration

Overgrazing by domestic animals destroys the grassland and contributes to the tragedy of the commons.

(©Richard Dibon-Smith, National Audubon Society Collection. Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

Trail Smelter arbitration

The Trail

Smelter

arbitration of 1938 and 1941 was a land-

mark decision about a dispute over

environmental degra-

dation

between the United States and Canada. This was the

first decision to recognize international liability for damages

caused to another nation, even when no existing treaty cre-

ated an obligation to prevent such damage.

A tribunal was set up by Canada and the United States

to resolve a dispute over timber and crop damages caused

by a smelter on the Canadian side of the border. The tribunal

decided that Canada had to pay the United States for dam-

ages, and further that it was obliged to abate the

pollution

.

In delivering their decision, the tribunal made an historic

and often-cited declaration: “Under the principles of interna-

tional law, as well as of the law of the United States, no

State has the right to use or permit the use of its territory

in such a manner as to cause injury by fumes in or to the

territory of another or the properties or persons therein,

when the case is of serious consequence and the injury is

established by clear and convincing evidence...” The case

1417

was landmark because it was the first to challenge historic

principles of international law, which subordinated interna-

tional environmental duty to nationalistic claims of sover-

eignty and free-market methods of unfettered industrial de-

velopment. The Trail Smelter decision has since become

the primary precedent for international

environmental law

,

which protects the

environment

through a process known

as the “web of treaty law.” International environmental law

is based on individual governmental responses to discrete

international problems, such as the Trail Smelter issue. Legal

decisions over environmental disputes between nations are

made in reference to a growing body of treaties, conventions,

and other indications of “state practices.”

The Trail Smelter decision has shaped the core princi-

ple underlying international environmental law. According

to this principle, a country which creates

transboundary

pollution

or some other environmentally hazardous effect

is liable for the harm this causes, either directly or indirectly,

to another country. A much older precedent for this same

principle is rooted both in Roman Law and Common Law:

sic utere ut alienum non laedas—use your own property in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Russell Eroll Train

such a manner as not to injure that of another. Prior to

the twentieth century, this principle was not relevant to

international law because actions within a nation’s borders

rarely conflicted with the rights of another. See also Acid

rain; Environmental Law Institute; Environmental liability;

Environmental policy; United Nations Earth Summit

[Kevin Wolf]

Russell Eroll Train (1920 – )

American environmentalist

Concern about environmental issues is a relatively recent

phenomenon worldwide. Until the 1960s, citizens were not

interested in air and

water pollution

, waste disposal, and

wetlands

destruction.

An important figure in bringing these issues to public

attention was Russell Eroll Train. He was born in James-

town, Rhode Island, on June 4, 1920, the son of a rear

admiral in the United States Navy. He attended St. Alban’s

School and Princeton University, from which he graduated

in 1941. After serving in the United States Army during

World War II, Train entered Columbia Law School, where

he earned his law degree in 1948.

Train’s early career suggested that he would follow a

somewhat traditional life of government service. He took a

job as counsel to the Congressional Joint Committee on

Revenue and Taxation in 1948 and five years later, became

clerk of the House Ways and Means Committee. In 1957,

Train was appointed a judge on the Tax Court of the United

States.

This pattern was disrupted, however, because of

Train’s interest in

conservation

programs. In 1961, he

founded the African Wildlife Leadership Foundation and

became its first head. He gradually began to spend more

time on conservation activities and finally resigned his judge-

ship to become president of the Conservation Foundation.

Train’s first environmental-related government ap-

pointment came in 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson

asked him to serve on the National Water Commission. The

election of Republican Richard Nixon late that year did not

end Train’s career of government service, but instead provided

him with even more opportunities. One of Nixon’s first ac-

tions after the presidential election was his appointment of a

20-member inter-governmental task force on

natural re-

sources

and the

environment

. The task force’s report criti-

cized the government’s failure to fund anti-pollution pro-

grams adequately, and it recommended the appointment of a

special advisor to the President on environmental matters.

In January 1969, Nixon offered Train another assign-

ment. The President had been sharply criticized by environ-

1418

mentalists for his appointment of Alaska Governor Walter

J. Hickel as Secretary of the Interior. To blunt that criticism,

Nixon chose Train to serve as Under Secretary of the Interior,

an appointment widely praised by environmental groups. In

his new position, Train was faced with a number of difficult

and controversial environmental issues, the most important

of which were the proposed

Trans-Alaska pipeline

project

and the huge new airport planned for construction in Flori-

da’s

Everglades National Park

. When Congress created

the

Council on Environmental Quality

in 1970 (largely as

a result of Train’s urging), he was appointed chairman by

President Nixon. The Council’s first report identified the

most important critical environmental problems facing the

nation and encouraged the development of a “strong and

consistent federal policy” to deal with these problems.

Train reached the pinnacle of his career in September

1973, when he was appointed administrator of the federal

government’s primary environmental agency, the

Environ-

mental Protection Agency

(EPA). During the three and

a half years he served in this post, he frequently disagreed

with the President who had appointed him. He often felt

that Nixon’s administration tried to prevent the enforcement

of environmental laws passed by Congress. Some of his most

difficult battles involved energy issues. While the administra-

tion preferred a laissez-faire approach in which the market-

place controlled energy use and prices, Train argued for

more controls that would help conserve energy resources

and reduce air and water

pollution

.

With the election of Jimmy Carter in 1976, Train’s

tenure in office was limited. He resigned his position at

EPA in March 1977 and returned to the Conservation Foun-

dation.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Schoenbaum, E. W. “Russell E. Train.” In Political Profiles. New York:

Facts on File, 1979.

P

ERIODICALS

Durham, M. S. “Nice Guy in a Mean Job.” Audubon (January 1974): 97–104.

Trans-Alaska pipeline

The discovery in March 1968 of oil on the Arctic slope of

Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay ignited an ongoing controversy over

the handling of the Arctic slope’s abundant energy resources.

Of all the options considered for transporting the huge quan-

tities found in North America’s largest field, the least hazard-

ous and most suitable was deemed a pipeline to the ice-free

southern port of Valdez.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Trans-Amazonian highway

Plans for the pipeline began immediately. Labeled

the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline System (TAPS) its cost was

estimated at $1.5 billion, a pittance compared to the final

cost of $7.7 billion. The total development cost for Prudhoe

Bay oil was likely over $15 billion, the most expensive

project ever undertaken by private industry. Antagonists,

aided by the nascent environmental movement, succeeded

in temporarily halting the project. Legislation that created

the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and re-

quired environmental impact statements for all federally-

related projects added new, critically important require-

ments to TAPS. Approval came with the 1973 Trans-

Alaskan Authorization Act, spurred on by the 1973 OPEC

embargo, the world’s first severe energy crisis. Construction

quickly resumed.

The pipeline is an engineering marvel, having broken

new ground in dealing with

permafrost

and mountainous

Arctic conditions. The northern half of the pipeline is

elevated to protect the permafrost, but river crossings and

portions threatened by avalanches are buried for protection.

A system was developed to keep the oil warm for 21

days in the event of a shutdown, to prevent TAPS from

becoming the “world’s largest tube of chapstick.” Especially

notable is Thompson Pass near the southern end, where

descent angles up to 45 degrees severely taxed construction

workers, especially welders.

Everything about TAPS is colossal: 799 mi (1,286

km) of 48-in (122-cm) diameter vanadium alloy pipe;

78,000 support columns; 65,000 welds; 15,000 trucks; and

peak employment of more than 20,000 workers. TAPS

has an operations control center linked to each of the 12

pump stations, with computer controlled flow rates and

status checks every 10 seconds.

The severe restrictions that the enabling act imposed

have paid off in an enviable safety record and few problems.

The worst problem thus far was caused by local sabotage

of an above-ground segment. In spite of its good record,

however, TAPS remains controversial. As predicted, it

delivers more oil than West Coast refineries can handle,

and efforts continue to allow exports to Japan.

In 2001, the Secure America’s Future Energy (SAFE)

Act, based on the President’s National Energy Policy,

stated among its goals the 2004 renewal of the existing

TAPS lease, along with the construction of a new pipeline

to transport

natural gas

from Alaska to the 48 contiguous

states. Another SAFE goal, the development of the

Arctic

National Wildlife Refuge

for

oil drilling

, is still heavily

backed in government despite a resounding Senate rejection

of the project in 2002. Both utilitarian conservationists

and altruistic preservationists are at loggerheads over energy

development in Alaska, while many native Inuits consider

1419

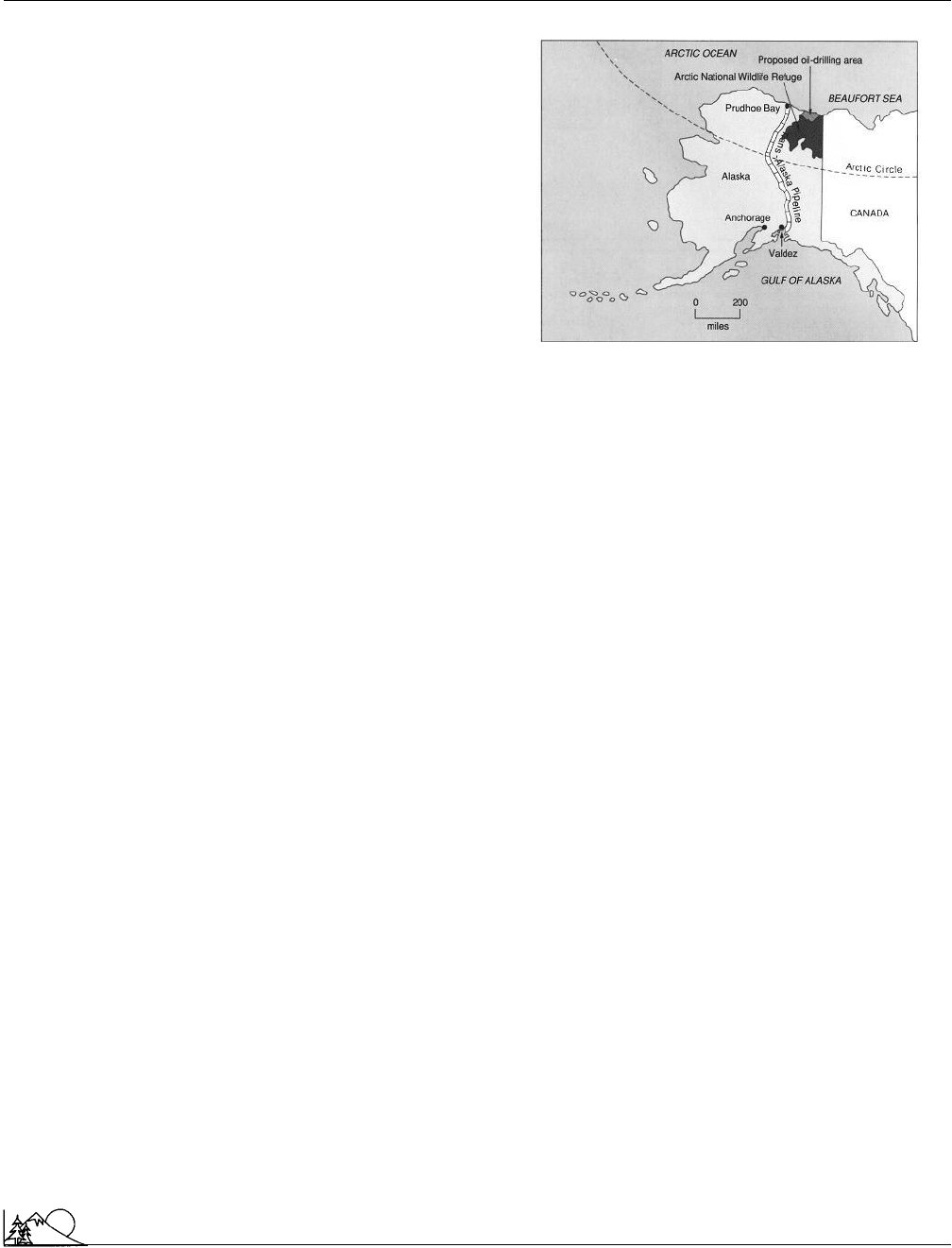

The route of the Trans-Alaska pipeline. (McGraw-

Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

this an opportunity to solidify their growing involvement

in the American economy. See also Oil drilling; Oil embargo

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dixon, M. What Happened to Fairbanks? The Effects of the Trans-Alaska

Oil Pipeline on the Community of Fairbanks, Alaska. Boulder: Westview

Press, 1978.

Roscow, J. P. 800 Miles to Valdez: The Building of the Alaska Pipeline.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1977.

P

ERIODICALS

Hodgson, B. “The Pipeline: Alaska’s Troubled Colossus.” National Geo-

graphic 150 (November 1976): 684–707.

Lee, D. B. “Oil in the Wilderness: An Arctic Dilemma.” National Geographic

174 (December 1988): 858–871.

Trans-Amazonian highway

The Trans-Amazonian highway begins in northeast Brazil

and crosses the states of Para and Amazonia. The earth

road, known as BR-230 on travel maps, was completed in

the 1970s during the military regime that ruled Brazil from

1964 until 1985. The highway was intended to further

land

reform

by drawing landless peasants to the area, especially

from the poorest regions of northern Brazil. More than

500,000 people have migrated to Transamazonia since the

early 1970s. Many of the colonists feel that the government

enticed them there with false promises.

The road has never been paved, so it is nothing but

dust in the dry season and an impassable swamp during the

wet season. Farmers struggle to make a living, with the

highway as their only means of transporting produce to

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transboundary pollution

market. When the rains come, large segments of the highway

wash away entirely, leaving the farmers with no way to

transport their crops. Small farmers live on the brink of

survival. Farmer Jose

´

Ribamar Ripardo says, “People grow

crops only to see them rot for lack of transport. It’s really

an animal’s life.” To survive in Amazonia, the colonists say,

they require a paved road to transport their produce.

The goal of repairing and paving the highway is viewed

with disfavor by many environmentalists. Roads through

Amazonia are perceived as being synonymous with destruc-

tion of the rain forests. Many environmental groups fear

that improved roads will bring more people into the area

and lead to increased devastation.

The Movement For Survival, spearheaded by Jose

´

Ger-

aldo Torres da Silva, claims that “If farmers could have techni-

cal help to invest in

nature

, they will be able to support their

families with just one third of their land lots, avoiding

defor-

estation

, the indiscriminate killing of numerous animal and

plant species.” Farmers in the region say that they can survive

on the land base that they have already acquired. They have

proposed preserving some natural vegetation by growing a

mixture of

rubber

and cacoa trees, which grow best in shaded

areas, so they will not have to devastate the forest. Efforts

are currently underway to establish extractivist preserves to

harvest rubber, brazil nuts, and other native products. Such

proposals for the use of the forest are a viable option, but they

are not enough. The environmentally friendly plans must also

take into account fluctuations in the market place. Brazil nuts,

for instance, are harvested in the unspoiled forest. When nut

prices fall onthe international market, the gatherers must have

other means of income to fall back on, without having to relo-

cate to a different part of the country.

Many residents of the area fear that if small farmers

do not have a reliable road to get produce to market, they

will have to leave the region. There is a real danger that

their lots will be sold to cattle ranchers, loggers, and invest-

ors. Small farmers have a track record of utilizing the land

in ways that are more environmentally sound than those

who follow in their wake.

[Debra Glidden]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Babbitt, B. E. “Amazon Grace.” New Republic 202 (25 June 1990): 18–19.

Fearnside, P. M. “Rethinking Continuous Cultivation in Amazonia: The

‘Yurimaguas Technology’ May Not Provide the Bountiful Harvest Predicted

by its Originators.” Bioscience 37 (March 1987): 209.

Ne

´

to, R. B. “The Transamazonian Highway.” Buzzworm 4 (November-

December 1992): 28–29.

Simpson, J. “To the Beginning of the World.” World Monitor 6 (January

1993): 34–41.

1420

Vesilind, P. J. “Brazil Moment of Promise and Pain.” National Geographic

171 (March 1987): 372–373.

Transboundary pollution

The most common interpretation of transboundary

pollu-

tion

is that it is pollution not contained by a single nation-

state, but rather travels across national borders at varying

rates. The concept of the global commons is important to

an understanding of transboundary pollution. As both popu-

lation and production increase around the globe, the poten-

tial for pollution to spill from one country to another in-

creases. Transboundary pollution can take the form of

contaminated water or the deposition of airborne pollutants

across national borders. Transboundary pollution can be

caused by catastrophic events such as the Chernobyl nuclear

explosion. It can also be caused by the creeping of industrial

discharge

that eventually has a measurable impact on adja-

cent countries. It is possible that pollution can cross state

lines within a country and would indeed be referred to as

transboundary pollution. This type of case is seldom held

up as a serious policy problem since national controls can

be brought to bear on the responsible parties and problems

can be solved within national borders. It is good to under-

stand how interstate environmental problems might develop

and to have knowledge as to those regulatory units of national

government that have jurisdiction.

Federalism is important in issues of national environ-

mental pollution largely because pollution can spread across

several states before it is contained. Within the United

States, it is the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA)

that writes the regulations that are enforced by the states.

The general rule is that states may enact environmental

regulations that are more strict than what the EPA has

enacted, but not less strict. In some cases interstate compacts

are designated by the EPA to deal with issues of

pollution

control

. An example of this is the regional compacts for

the management of low level

radioactive waste

materials.

These interstate compacts meet and make policy for the

siting and management of facilities, the transport of materials

and the long term planning for adequate and safe storage

of

low-level radioactive waste

until its

radioactivity

has

been exhausted. Other jurisdictions such as this in the U.S.

deal with transboundary issues of

air quality

,

wildlife man-

agement

, fisheries,

endangered species

,

water quality

,

and solid

waste management

. Federalism has been mani-

fested in specific legislation. The

National Environmental

Policy Act

(NEPA) is an attempt to clarify and monitor

environmental quality regardless of state boundaries. NEPA

provides for a council to monitor trends. The

Council on

Environmental Quality

is a three-member council ap-

pointed by the President of the United States to collect data

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transboundary pollution

at the national level on environmental quality and manage-

ment, regardless of jurisdiction. This picture at a national

level is vastly complicated when moved to a global level.

There is increasing demand for dialogue and support

for institutions that can address impacts on the global com-

mons. The issue of “remedies” for transboundary pollution

is usually near the top of the agenda. Remedies frequently

take the form of payments to rectify a wrong, but more often

take the form of fines or other measures to assure compliance

with best practices. The problem with this approach is that

charges have to be high enough to offset the cost of control-

ling “creeping” pollution that might cross national borders

or the cost of monitoring production processes to prevent

predictable disasters.

Marine pollution

is an excellent exam-

ple of a transboundary pollution problem that involves many

nation-states and unlimited point sources of pollution. Ma-

rine pollution can be the result of on-shore industrial pro-

cesses that use the ocean as a waste disposal site. Ships at

sea find the ocean just too convenient as a sewer system,

and surface ocean activities such as

oil drilling

are a constant

source of pollution due to unintentional discharges. Acci-

dents at sea are well-documented, the most famous in recent

years being the

Exxon Valdez

oil spill off of Alaska in

Prince

William Sound

in 1989. Earlier, in 1969 an international

conference on marine pollution was held. As a result of

this conference two treaties were developed and signed that

would respond to oil pollution on the high seas. These

treaties were not fully ratified until 1975. The Convention

on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of

Wastes and Other Matter and The Convention for the

Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping from Ships and

Aircraft cite specific pollutants that are considered extremely

detrimental to marine environments. These pollutants are

organohalogenic compounds and mercury, as well as slightly

less harmful compounds such as lead, arsenic, copper, and

pesticides. The specificity of those treaties that deal with

ocean environments indicate a rising commitment to the

control of transboundary pollution carried by the ocean’s

currents and helped to resolve the question of remedies in

the Valdez catastrophe.

Acid rain

is a clear example of how air currents can

carry destructive pollution from one nation-state to another,

and indeed, around the globe. Air as a vector of pollution

is particularly insidious because air patterns, although

known, can change abruptly, confounding a country’s at-

tempt to monitor where pollutants come from.

Acid deposi-

tion

has been an international issue for many years. The

residuals from the burning of

fossil fuels

and the byproducts

from radiation combine in the upper

atmosphere

with

water vapor and precipitate down as

acid

rain. This precipi-

tation is damaging to lakes and streams as well as to forests

and buildings in countries that may have little sulfur and

1421

nitrogen

generation of their own. The negative justice of

this issue is that it is the most industrialized nations that

are producing these pollutants due to increased production

and too often the pollution rains down on developing coun-

tries that have neither the resources nor the technical exper-

tise to clean up the mess. Only recently, due to international

agreements between nation-states, has there been significant

reduction in the deposition of acid rain. The

Clean Air Act

Amendments of 1990 in the United States helped to reduce

emissions from coal-burning plants. In Europe, sulfur emis-

sions are being reduced due to an agreement among eight

countries. The European Community in 1992 agreed to

implement

automobile emission standards

similar to

what the United States agreed to in the early 1980s. In 1994

all large automobiles in Europe were required to reduce

emissions with the installation of catalytic converters. These

measures are all aimed at reducing transboundary pollution

due to air emissions.

Probably the most famous case of transboundary river

pollution is that of the Rhine River with its point of incidence

in Basel, Switzerland. This was a catastrophe of great propor-

tions. The source of pollution was an explosion at a chemical

plant. In the process of putting out the fire, great volumes

of water were used. The water mixed with the

chemicals

at the plant (mercury, insecticides, fungicides, herbicides

and other

agricultural chemicals

), creating a highly toxic

discharge. This lethal mixture washed into the Rhine River

and coursed its way to the Baltic Sea, affecting every country

along the way. Citizens of six sovereign nations were affected

and damage was extensive. There was further consternation

when compensation for damage was found to be difficult to

obtain. Although the chemical company volunteered to pay

some compensation it was not enough. It was possible that

each affected nation-state could try the case in their own

national court system, but how would collection for damages

take place? “In transboundary cases, if there is no treaty or

convention in force, by what combination of other interna-

tional law principles can the rules of liability and remedy be

determined?” It becomes problematic to institute legal action

against another country if there is no precedent. Since there

is no history of litigation between nation-states in cases of

environmental damage there is no precedent to determine

outcome. Historically, legal disputes have been resolved (al-

beit, extremely slowly) through negotiations and treaties.

There is no “polluter pays” statute in international law doc-

trine.

The authority that can be brought to bear on issues

of transboundary pollution is weak and confusing. The only

mechanism that is currently available to compensate injury

is private litigation between parties and that is difficult due

to a lack of agreements to enforce civil judgments. If, in

fact, the polluter is the national government, as in the case

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transfer station

of the Chernobyl disaster, it may be nearly impossible to

gain compensation for damages.

Transboundary pollution takes many forms and can

be perpetrated by both private industry and government

activities. It is difficult if not impossible to litigate on an

international scale. It is in fact sometimes difficult to deter-

mine who the polluter is when the pollution is “creeping”

and not a catastrophic incidence. Airborne transboundary

pollution is extremely difficult to track due to the pervasive

nature of the practices that produce it. Global solutions to

transboundary pollution can only be successful if all nations

agree to implement controls to reduce known pollutants

and to take responsibility for accidents that damage the

environmental quality of other nations.

[Cynthia Fridgen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Buck, S. J. Understanding Environmental Administration and Law. Wash-

ington, DC: Island Press, 1996.

Plater, Z. J. B., R. H. Abrams, and W. Goldfarb. Environmental Law and

Policy: Nature, Law, and Society. St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1992.

World Wildlife Fund. “Choosing a Sustainable Future: The Report of

the National Commission on the Environment.” Washington, DC: Island

Press, 1993.

P

ERIODICALS

Bernauer, T., and P. Moser. “Reducing Pollution of the River Rhine: The

Influence of International Cooperation in The Journal of Environment &

Development.” Sage Periodicals Press 5, no. 4 (December 1996).

Transfer station

The regional disposal of

solid waste

requires a multi-stage

system of collection, transport, consolidation, delivery, and

ultimate disposal. Many states and counties have established

transfer stations, where solid waste collected from curbsides

and other local sources by small municipal

garbage

trucks

is consolidated and transferred to a larger capacity vehicle,

such as a refuse transfer truck, for

transportation

to a

disposal facility. Typically, municipal garbage trucks have a

capacity of 20 cubic yd (15.3 cubic m) and refuse transfer

trucks may have a capacity of 80–100 cubic yd (61–76.4

cubic m). The use of transfer stations reduces hauling costs

and promotes a regional approach to

waste management

.

See also Garbage; Landfill; Municipal waste; Tipping fee;

Waste stream

Transmission lines

Transmission lines are used to transport electricity from

places where it is generated to places where it is used. Almost

1422

all electricity in North America is generated in fossil-fueled,

nuclear-fueled, or hydroelectric generating stations. These

are located some distance away from the factories, businesses,

institutions, and homes where the electricity is actually used,

in some cases hundreds of miles away, so that the electricity

must be transmitted from the generating stations to these

diverse locations.

Transmission lines are strung between tall, well-spaced

towers and are linear features that appropriate long, narrow

areas of land. Most transmission lines carry a high voltage of

alternating current, typically ranging from about 44 kilovolts

(kV) to as high as 750 or more kV (some transmission lines

carry a direct current, but this is uncommon). Transmission

lines typically feed into lower-voltage distribution lines,

which typically have voltage levels less than about 35 kV

and an alternating current (in North America) of 60 Hertz

(Hz; this is equivalent to 60 cycles of positive to negative

per second), and is usually 50 Hz in Europe.

Electrical fields are generated by transmission lines

(and by all electrical appliances), with the strength of the

field being a function of the voltage level of the current

being carried by the powerline. The flow of electricity in

transmission lines also generates a magnetic field. Electric

fields are strongly distorted by conducting objects (including

the human body), but magnetic fields are little affected and

freely pass through

biomass

and most structures. Electric

and magnetic fields both induce extremely weak electrical

currents in the bodies of humans and other animals. These

electrical currents are, however, several million times weaker

than those induced by the normal functions of certain cells

in the human body.

Transmission lines are controversial for various rea-

sons. These include their poor aesthetics, the fact that they

can destroy and fragment large areas of natural lands or take

large areas out of other economically productive land-uses,

and the belief of many people that low-level health risks are

associated with living in the vicinity of these structures.

Aesthetics of transmission lines

Transmission lines are very long, tall, extremely promi-

nent linear features. Transmission lines have an unnatural

appearance and their very presence disrupts the visual aes-

thetics of natural landscapes, as viewed from the ground or

the air. As such, transmission lines represent a type of “visual

pollution” that detracts from otherwise pleasing natural or

pastoral landscapes. These aesthetic damages are an impor-

tant environmental impact of almost all rural transmission

lines. Similarly, above-ground transmission lines in urban

and suburban areas are not regarded as having good aes-

thetics.

Damages to natural values

Apart from difficult crossings of major rivers and

mountainous areas, transmission lines tend to follow the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transmission lines

shortest routes between their origin and destination. Often,

this means that intervening natural areas must be partially

cleared to develop the right-of-way for the transmission line.

This can result in permanent losses of natural

habitat

,as

typically happens when forests are cleared to develop a pow-

erline right-of-way. Moreover, it is not feasible to allow trees

to regenerate beneath a transmission line because they can

interfere with the operation and servicing of the powerline.

For these reasons, vegetation is cleared beneath and

to the sides of transmission lines (for a width of about

one tree-height). This can be done by periodically cutting

shrubby vegetation and young trees or by the careful use of

herbicides, which can kill shrubs and trees while allowing

the growth of grasses and other herbaceous plants.

These sorts of management practices result in the con-

version of any original, natural habitats along a transmission

right-of-way into artificial habitats. The ecological effects

include a net loss of natural habitats and fragmentation

of the remainder into smaller blocks. In addition, roads

associated with the construction and maintenance of trans-

mission lines may provide relatively easy access for hunters,

anglers, and other outdoor recreationalists to previously re-

mote and isolated natural areas. This can result in increased

stress for certain wild

species

, especially hunted ones, as

well as other ecological damages.

Some studies of transmission lines have found that

hypothesized ecological damages did not occur or were un-

important. For example, naturalists suggested that the con-

struction of extensive hydroelectric transmission lines in the

boreal forest of northern Quebec would impede the move-

ments of woodland caribou. In fact, this did not occur, and

caribou were sometimes observed to use the relatively open

transmission corridors during their migrations and as resting

places. Similar observations have been made elsewhere for

moose, white-tailed deer, and other ungulates. Predators of

these animals, such as

wolves

and coyotes, will also freely

move along transmission corridors, unless they are frequently

disturbed by hunters, recreationalists, or maintenance crews.

Certain birds of prey, particularly osprey, may use

transmission poles or pylons as a platform upon which to

build their bulky nests, which may be used for many years. In

some cases the birds are considered a management problem,

especially if their nests get large enough to potentially short

out the powerlines or if the parent birds aggressively defend

their nests against linesmen attempting to repair or maintain

the transmission line. Fortunately, it is relatively easy to

move the nests during the nonbreeding season and to place

them on a “dummy” pole located for the purpose beside the

transmission line. In most cases, the ospreys will readily use

the relocated nest in subsequent years.

Transmission lines also pose lethal risks for certain

kinds of birds, especially larger species that may inadvertently

1423

collide with wires, severely injuring themselves. There have

also been cases of raptors and other large birds being electro-

cuted by settling on transmission lines, particularly if they

somehow span adjacent wires with their wings.

Disruption of land-use

Some economically important land-uses can occur be-

neath transmission lines, for example, forestry and some

types of agriculture. Other land-uses, however, are not com-

patible with the immediate proximity of high-voltage trans-

mission lines, particularly residential land-uses. In cases of

land-use conflicts, opportunities are lost to engage in certain

economically productive uses of the land, a context that

detracts from benefits that are associated with the construc-

tion and operation of the transmission line.

Many people, including some highly qualified scien-

tists, believe that low-level health risks may be associated

with longer-term exposures to the electric and magnetic

fields that are generated by transmission lines. These in-

creased risks mean that people living or working in the

vicinity of these industrial structures may have an increased

risk of developing certain diseases or of suffering other dam-

ages to their health.

Although people are routinely exposed to electromag-

netic fields through the operation of electrical appliances in

the home or at work, those exposures are typically intermit-

tent. In contrast, continuous electromagnetic fields are gen-

erated by transmission lines, so longer-term exposures can

be relatively high. It must be understood, however, that the

scientific knowledge in support of the low-level health risks

associated with transmission lines is incomplete and equivo-

cal and therefore highly controversial.

In particular, some studies have suggested that long-

term exposure to electromagnetic fields generated by high-

voltage transmission lines may be associated with an elevated

incidence of certain types of cancers. The strongest sugges-

tions have been for increased risks of childhood

leukemia

.

There is weaker evidence of increased risks of cancers of the

lymphatic and nervous systems and of adult leukemia. It

must be remembered, however, that not all epidemiological

studies of transmission lines have reported these statistical

relationships and that the increased risks are rather small

when they are found. Studies have also been made of possible

increases in the incidences of migraine headaches, mental

depression, and reproductive problems associated with

longer-term exposures to electromagnetic fields near trans-

mission lines. The results of these studies are inconsistent

and equivocal.

Some researchers who have assessed the medical prob-

lems potentially associated with high-voltage transmission

lines have concluded that it would be prudent to not have

people living in close proximity to these industrial structures.

Even though there is no strong and compelling evidence that

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transpiration

medical problems are actually occurring, the precautionary

approach to environmental management dictates that the

potential risks should be avoided to the degree possible. It

would therefore be sensible for people to avoid living within

about 54.5 yd (50 m) or so of a high-voltage transmission

line, and they should avoid frequently using the right-of-

way as travel corridors.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Carpenter, D. O., and S. Ayrapetyan. Biological Effects of Electric and Mag-

netic Fields. Vols.1&2.SanDiego: Academic Press, 1994.

Levallois, P., and D. Gauvin. Risks Associated with Electromagnetic Fields

Generated by Electrical Transmission and Distribution Lines. Great Whale

Environmental Assessment: Background Paper No. 9, Part 1. Montreal,

PQ: Great Whale Public Review Support Office. 1994.

P

ERIODICALS

Alonso, J. C., J. A. Alonso, and R. Munoz-Pulido. “Mitigation of Bird

Collisions with Transmission Lines through Ground-wire Marking.” Biol-

ogy Conservation 67 (1994): 129–134.

Coleman, M. P., et al. “Leukemia and Residence Near Electricity Transmis-

sion Equipment: A Case-control Study.” British Journal of Cancer 60 (1989):

793–798.

Feychting, M., and A. Ahlbom. “Magnetic Fields and Cancer in Children

Residing Near Swedish High-voltage Power Lines.” American Journal of

Epidemiology 138 (1993): 467–481.

London, S. J., et al. “Exposure to Residential Electric and Magnetic Fields

and Risk of Childhood Leukemia.” American Journal of Epidemiology 134

(1991): 923–927.

Steenhof, K., M. A. Kochert, and J. A. Roppe. “Nesting by Raptors and

Common Ravens on Electrical Transmission Line Towers.” Journal of

Wildlife Management, 57 (1993): 271–281.

Transpiration

Transpiration is the process by which plants give off water

vapor from their leaves to the

atmosphere

. The process is

an important stage in the water cycle, often more important

in returning water to the atmosphere than is evaporation

from rivers and lakes. A single acre of growing corn, for

example, transpires an average of 3,500 gal (13,248 l) of

water per acre (0.4 ha) of land per day. Transpiration is,

therefore, an important mechanism for moving water

through the

soil

, into plants, and back into the atmosphere.

When plants are removed from an area, soil retains more

moisture and is unable to absorb rain water. As a conse-

quence,

runoff

and loss of nutrients from the soil is likely

to increase. See also Erosion; Flooding; Soil conservation;

Soil fertility

1424

Transportation

For several million years, humans got to where they wanted

to go by one means: walking. This, of course, greatly limited

the distance of travel and the amount of items that could

be transported. Today, transportation is accomplished in the

air, on land, and in water. It ranges from carts pulled by

horses or oxen and dirt roads in Africa to the Concorde

supersonic airplane that can travel from Paris to New York

in four hours.

The first changes in transportation came about five to

six thousand years ago in three areas: the introduction of

boats, the domestication of wild horses, and the invention

of the wheel. Horse domestication started about 6,000 years

ago, probably occurring in several different parts of the world

at about the same time. Riding astride the horse may have

begun in Turkestan before 3,000

B.C.

At about the same

time, many historians believe the wheel was invented in

Mesopotamia, a development that drastically changed the

way people moved about. It was not long before the wheel

found its way onto platforms, forming carts that could be

drawn by horses or oxen. Covered wagons and carriages

soon followed. It is difficult to say when boats became a

means of transportation but ships can be traced back at least

to the ancient Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, and Egyptian

empires

In ancient Egypt, the main transportation corridor was

the Nile River, where ships carried people and trading goods

through the empire. On land, transportation was more diffi-

cult. Ordinary people traveled by foot, while high nobles

were carried in chairs or covered litters. Over times, these

became more elaborate, requiring as many as 28 people to

carry them. Lower ranking nobles often rode on a chair

fastened on the backs of donkeys. Horse-drawn chariots first

appeared in Egypt about 3,500 years ago.

Wheeled vehicles were first used primarily as hearses

for the great and as military adjuncts until they gradually

came to be used more for carriers of goods. Even during

the Classical Age in Greece, chariots were declining in im-

portance for warfare, and they were finally used only for

sport. In early times carts with shafts for single animals were

preferred in outlying countries where roads were poor, but

with improvement in roads came heavy wagons and the use

of several animals for power.

Ships took on an ever increasingly important role in

transportation starting about

A.D.

1400, when ships of explo-

ration sailed from Europe to Asia and the New World. By

the seventeenth century, ships regularly carried European

settlers to North America. These settlers soon began build

their own transportation system, using boats on rivers and

coastal waterways and horse and cart by land.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Transportation

From 1600 to 1754 travel between the American colo-

nies was accomplished most quickly and easily by boat. Ev-

erywhere in colonial America settlements sprang up first

near navigable rivers. Two types of river vessel were common

along colonial rivers. Dugout canoes carried small cargoes,

while long (up to 40 ft [12 m]), flat-bottomed boats handled

larger loads. River travel everywhere in America was slow

and dangerous. Nevertheless, rivers served colonists every-

where as routes for their goods, travel, and communication.

Land travel between seventeenth-century colonies

could be difficult as well. The number and condition of

roads varied widely from colony to colony, depending heavily

on the density of settlement and the support provided by

the various colonial legislatures. In many places roadbeds

were poor and bridges few. By the 1760s one of the longest

roads, the Great Wagon Road, stretched nearly 800 mi

(1,287 km) along old Indian trails through western Pennsyl-

vania and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley to Georgia. The

longest road in North America was the Camino Real, which

connected Mexico City to Santa Fe, an 1,800-mi (2,897-

km) trip that took wagon trains six months to complete.

Aside from walking and riding a horse, a person in

eighteenth-century America had other means of traveling.

Farmers used two-wheeled carts while Indian traders fre-

quently had packhorses. During this era, the Conestoga

wagon came to the forefront. A high-wheeled vehicle with

a canvas cover, it had a curved bottom in order to keep its load

from shifting. As may be expected, the Conestoga quickly

became popular. By the 1770s more than 10,000 were in

use in Pennsylvania while in the South Carolina backcountry

there were an estimated 3,000. Several stagecoach lines oper-

ated between all the major cities in the north. The most

heavily traveled route, between New York and Philadelphia,

was served twice weekly by a stagecoach.

The 1800s saw the advent of two more means of

transportation: the steamboat and the railway. Hundreds of

steamboats once navigated rivers in the eastern half of the

United States railways caught on throughout the world and

are the primary form of inner-city

mass transit

in many

countries, such as India. In the twentieth century, two more

forms of transportation came into existence: the

automobile

and airplane. The electric streetcar also gained in popularity,

finding itself in many major American cities, including San

Francisco, Los Angeles, and New Orleans.

In many parts of the world today, mass transit systems

are an important component of a nation’s transportation

system. Where people can not afford to buy automobiles,

they depend on bicycles, animals, or mass transit systems

such as bus lines to travel within a city and from city to city.

In the United States the automobile is the primary

form of transportation. It is less important in most other

parts of the world. Mass transportation, or mass transit,

1425

does play a role in the United States. One could argue

that stagecoaches were the first mass transit vehicles in the

country, since they could hold eight to 10 passengers, a big

improvement over one person on a horse or several people

in a small horse-drawn buggy. In the twentieth and twenty-

first centuries, the horse has been replaced with the automo-

bile. Today, mass transit options include airplanes, buses,

trolleys, rail and light rail, and subways. The world’s first

subway opened in London in the late nineteenth century,

soon followed by America’s first subway in New York.

Most of these forms of transportation brought with

them problems, including harming the

environment

. Elec-

tric trains, trolleys, and streetcars are essentially pollution-

free but it takes addition

power plants

to run them, plants

that often use highly polluting fuels such as

coal

and oil.

Autos, buses, and airplanes are mostly oil-dependent. It was

not until the 1970s that the public began to be concerned

with the toxic effects of emissions from these transportation

conveyances. Since then, airplanes, buses, and autos have

increasingly become less polluting. This, however, has been

offset by an increase in their numbers.

Mass transit usage reached its peak in the United

States in the 1940s and 1950s. During the 1960s mass transit

systems and their ridership declined drastically even as urban

populations grew. There was a brief resurgence in the 1970s

as the price of

gasoline

skyrocketed. In 1972, the country

embarked on a round of new mass transit systems when

the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), opened in the San

Francisco Bay Area. BART was followed in the next two

decades by new subway, bus, light rail, and trolley systems

in Washington, D.C., San Diego, Atlanta, Baltimore, Los

Angeles, San Jose, California, and other urban areas. At

about the same time, the United States Congress gave the

nation’s inner-city passenger rail system, Amtrak, a new lease

on life. Amtrak proved to be a huge success among inner-

city passengers, but the federal government has never main-

tained the consistent support of the system it showed during

the aftermath of the

petroleum

price hikes of the 1970s.

Over the next several decades, urban planners see little

likelihood of entirely new types of mass transportation.

Rather, they expect improvements over existing bus, trolley,

and light rail systems. And at least one idea that has been

around for 50 years is getting a new look. When the monorail

was introduced at Disneyland in California in 1955, it was

hailed as the clean, fast, and efficient transit system of the

future. Up until now, it never caught on, other than a very

short single-line monorail that opened in Seattle in 1962.

But urban planners are taking a fresh look at monorails,

which are attractive because they could be built above existing

highways. Las Vegas has begun building a $650 million

monorail. The four-line will parallel the heavily congested

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Tributyl tin

main thoroughfare, the Strip, carrying an estimated 19 mil-

lion passengers when it opens in 2004.

[Ken R. Wells]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lewis, David, and Fred Laurence Williams. Policy and Planning as Public

Choice: Mass Transit in the United States. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publish-

ing Co., 1999.

P

ERIODICALS

Brovarski, Edward. “Getting Around in the Old Kingdom.” Calliope (Sep-

tember 2001): 19.

Gould, Lark Ellen. “Making Tracks: Las Vegas is Preparing for a Well-

Needed Monorail System That Will Move People From Hotel to Hotel.”

Travel Agent (March 4, 2002): SS6–SS7.

National Geographic Society. “Cleaner Living and Driving.” National Geo-

graphic (May 2001): XIV.

National League of Cities. “Technology Improves City Transportation

Flow, Safety.” Nation’s Cities Weekly (July 3, 2000): 5.

Reynolds, Francis D. “The Transportation System of The Future.” The

Futurist (September 2001): 44.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Department of Transportation, 400 7th Street NW, Washington, DC

USA 20590 202-366-4000, Email: dot.comments@ost.dot.gov, <http://

www.transportation.gov>

Trash

see

Solid waste

Treespiking

see

Monkey-wrenching

Tributyl tin

Tributyl tin (TBT) is a synthetic organic tin compound that

is primarily used as an additive to paints. In this application,

TBT acts as a biocide or compound that kills plants such

as algae, fungus, mildew, and mold that grow in or on the

surface of the coating. These antifouling paints, as they are

called, are applied to the hulls of ships to prevent sea life

(e.g., barnacles and algae) from attaching to the hull. Growth

of organisms on the hulls of ships causes ships to slow down

and increases fuel consumption due to increased drag. Ships

that are covered with these organisms can also transport

non-native, or invasive,

species

around the world, which

can disrupt an

ecosystem

and cause reductions in biological

diversity. TBT is also used in lumber preservatives as an

industrial biocide.

TBT-based paints were introduced more than 40 years

ago. The first TBT anti-fouling paints, known as Free Asso-

1426

ciation Paints (FAPs), where the TBT is mixed into the

paint, prevented fouling by uncontrolled

leaching

of TBT

into the

environment

. Starting 20 years ago, FAPS were

gradually phased out and replaced with TBT Self Polishing

Copolymer Paints, in which the TBT is bound in the paint

matrix. This type of formulation allows for TBT to be re-

leased slowly and uniformly.

TBT, also known as organotin, is a widespread con-

taminant of water and sediments in harbors, shipyards, and

waterways. TBT is persistent in marinas, estuaries, and other

waters where circulation is poor and flushing irregular. In the

natural aquatic environment, degradation of TBT through

biological processes is the most important pathway for the

removal of this toxic compound from the water column. At

levels of TBT contamination typical of contaminated surface

waters, the

half-life

is six days to four months. Half-life

refers to the amount of time it takes for one-half of the

TBT to be eliminated from the environment through natural

means.

TBT has been shown to have significant environmen-

tal impact and is considered to be an endocrine disruptor

that affects the immune and reproductive systems. In mol-

luscs, TBT can be found in concentrations that are up to

250,000 times higher than in the surrounding

sediment

or

seawater. Contaminated molluscs had deformed shells, slow

growth rates, and poor reproduction, with eggs and larvae

often dying. Exposure to TBT has resulted in sex change

and infertility in at least 50 species of snails. In the dogwhelk,

which is a small marine snail, TBT causes the female snail

to grow a penis that blocks the oviduct and thus prevents

reproduction. This abnormality is referred to as “imposex,”

and its development has been linked to the concentrations

of TBT in tissue. Because of this association, imposex in

the dogwhelk has been used as an indicator of TBT

pollu-

tion

. TBT has also been detected in large predators such

as

sharks

,

seals

, and

dolphins

, indicating that TBT can

accumulate in the food chain, as larger animals eat smaller

animals contaminated with TBT. Currently, not enough

data are available to help researchers determine whether

TBT is a human

carcinogen

, so the U.S.

Environmental

Protection Agency

(EPA) has assigned it to the “cannot

be determined” category.

Environmental concerns over the effects of TBT-

based paints has led to the regulatory control of TBT

throughout the world. In 1988, the United States enacted

the Organotin Antifouling Paint Control Act that restricts

the use of TBT-based antifoulants to ships larger than 25

meters in length or those with

aluminum

hulls. The Act

also restricted the release rate of TBT from the antifouling

paints. In 1990, the International Maritime Organization

(IMO) of the United Nations’ Marine Environment Protec-

tion Committee adopted a resolution that recommended