Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Composting

are less able to take advantage of subtle differences in an

environment. Situations in which one species of plant takes

over an area, causing the extinction of competitors, are well

known.

One mechanism that plants use in this battle with

each other is the release of toxic

chemicals

, known as allelo-

chemicals. These chemicals suppress the growth of plants

in other—and, sometimes, the same—species. Naturally oc-

curring antibiotics are examples of such allelochemicals.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Moran, J. M., M. D. Morgan, and J. H. Wiersma. Environmental Science.

Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown, 1993.

Competitive exclusion

Competitive exclusion is the interaction between two or

more

species

that compete for a resource that is in limited

supply. It is n ecological principle involving competitors with

similar requirements for

habitat

or resources; they utilize a

similar

niche

. The result of the

competition

is that one or

more of the species is ultimately eliminated by the species

that is most efficient at utilizing the limiting resource, a

driving force of

evolution

. The competitive exclusion princi-

ple or “Gause’s principle” states that where resources are

limiting, two or more species that have the same require-

ments for the limiting resources cannot co-exist. The co-

existing species must therefore adopt strategies that allow

resources to be partitioned so that the competing species

utilize the resources differently in different parts of the habi-

tat, at different times, or in different parts of the life cycle.

[Marie H. Bundy]

Composting

Composting is a fermentation process, the break down of

organic material aided by an array of

microorganisms

,

earthworms, and other insects in the presence of air and

moisture. This process yields compost (residual organic ma-

terial often referred to as

humus

), ammonia,

carbon diox-

ide

, sulphur compounds, volatile organic acids, water vapor,

and heat. Typically, the amount of compost produced is 40–

60% of the volume of the original waste.

For the numerous organisms that contribute to the

composting process to grow and function, they must have

access to and synthesize components such as

carbon

,

nitro-

gen

, oxygen,

hydrogen

, inorganic salts, sulphur,

phospho-

297

rus

, and trace amounts of micronutrients. The key to initiat-

ing and maintaining the composting process is a carbon-to-

nitrogen (C:N) ratio between 25:1 and 30:1. When

C:N

ratio

is in excess of 30:1, the

decomposition

process is

suppressed due to inadequate nitrogen limiting the

evolu-

tion

of bacteria essential to break the strong carbon bonds.

A C:N ratio of less than 25:1 will produce rapid localized

decomposition with excess nitrogen given off as ammonia,

which is a source of offensive odors.

Attaining such a balance of ratio and range is possible

because all organic material has a fixed C:N ratio in its

tissue. For example,

food waste

has a C:N ratio of 15:1,

sewage

sludge

has a C:N ratio of 16:1, grass clippings have

a C:N ratio of 19:1, leaves have a C:N ratio of 60:1, paper

has a C:N ratio of 200:1, and wood has a C:N ratio of 700:1.

When these (and other) materials are mixed in the right

proportions, they provide optimum C:N ratios for compost-

ing. Typically, nitrogen is the limiting component that is

encountered in waste materials and, when insufficient nitro-

gen is present, the composting mixture can be augmented

with agricultural fertilizers, such as urea or ammonia nitrate.

In addition to nutrients, the efficiency of the compost-

ing process depends on the organic material’s size and surface

characteristics. Small particles provide multi-faceted surfaces

for microbial action. Size also influences porosity (crevices

and cracks which can hold water) and permeability (circula-

tion or movement of gases and moisture).

Moisture (water) is an essential element in the biologi-

cal degradation process. A moisture level of 55–60% by

weight is required for optimal microbial,

nutrient

, and air

circulation. Below 50% moisture, the nutrients to sustain

microbial activity become limited; above 70% moisture, air

circulation is inhibited.

Air circulation controls the class of microorganisms

that will predominate in the composting process: air-breath-

ing microorganisms are collectively termed

aerobic

, while

microorganisms that exist in the absence of air are called

anaerobic

. When anaerobic microorganisms prevail, the

composting process is slow, and unpleasant-smelling ammo-

nia or hydrogen sulfide is frequently generated. Aerobic

microorganisms will quickly decompose organic material

into its principal components of carbon dioxide, heat and

water.

The role of acidity and alkalinity in the composting

process depends upon the source of organic material and

the predominant microorganisms. Anaerobic microorgan-

isms generate acidic conditions which can be neutralized

with the addition of lime. However, such adjustments must

be done carefully or nitrogen imbalance will occur that can

further inhibit biological activity and produce ammonia gas,

with its associated unpleasant odor. Organic material with

a balanced C:N ratio will initially produce acidic conditions,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Composting

6.0 on the

pH

scale. However, at the end of the process

cycle, mature compost is alkaline, with a pH reading greater

than 7.0 and less than 8.0.

The regulation and measurement of temperature is

fundamental to achieving satisfactory processing of organic

materials. However, the effect of ambient or surface temper-

atures on the process is limited to periods of intense cold

when biological growth is dormant. Expeditious processing

and reduction of herbicides, pathogens, and pesticides is

achieved when internal temperatures in the compost pile

are maintained at 120–140°F (55–l60°C). If the internal

temperature is allowed to reach or exceed 150°F (65°C),

biological activity is inhibited due to heat stress. As the

nutrient content is depleted, the internal temperature de-

creases to 85°F (30°C) or less–one criteria for defining mature

or stabilized compost.

Mature or stabilized compost has physical, chemical,

and biological properties which offer a variety of attributes

when applied to a host

soil

. For example, adding compost

to barren or disturbed soils provides organic and microbial

resources. The addition of compost to clay soils enhances

the movement of air and moisture. The water retention

capacity of sandy soil is enhanced by the addition of compost

and

erosion

also is reduced. Soils improved by the addition

of compost also display other characteristics such as en-

hanced retention and exchange of nutrients, improved seed

germination, and better plant root penetration. Compost,

however, has insufficient nitrogen, phosphorous, and potas-

sium content to qualify as a

fertilizer

. The ultimate applica-

tion or disposition of compost depends upon its quality, which

is a function of the type of organic material and the meth-

od(s) employed to enhance or control processing.

Compost processing can be as simple as a plastic

gar-

bage

bag filled with a mixture of plant waste that has had

a couple of ounces of fertilizer, some lime, and sufficient

water added to make the material moist. The bag is then

sealed and set aside for about 12 months. Faster processing

can be achieved with the use of a 55 gal (208 l) drum

into which 0.5-in (1.3-cm) holes have been drilled for air

circulation. Filled with the same mixture as the garbage bag

and rotated at regular intervals, this method will produce

compost in two to three months. A multi-compartmental-

ized container is faster and increases the diversity of materials

which can be processed. However, including such items as

fruit and vegetable scraps, meat and dairy products, card-

board cartons, and fabrics must be undertaken with caution

because they attract and breed vermin.

Such methods are designed for individual use, espe-

cially by those who can no longer dispose of garden waste

with their

household waste

. Similarly, commercial and

government institutions employ natural (low), medium, and

advanced technical composting methods, depending on their

298

motivation, i.e., diminishing

landfill

capacity, availability of

fiscal resources, and commitment to

recycling

. The simplest

composting method currently employed by industry and mu-

nicipalities entails dumping

organic waste

on a piece of

land graded (sloped) to permit precipitation and leachate

(excess moisture and organics from composting) to collect

in a retention pond. The pond also serves as a source of

moisture for the compost process and as a system where

photosynthesis

can oxidize the leachate. The organic mate-

rial is placed in piles called windrows (a ridge pile with a

half-cone at each end). The dimensions of a windrow are

typically 10–12 ft (3–3.7 m) wide at the base and about 6

ft (1.8 m) high at the top of the ridge. The length is site

specific. Windrows are constructed using a front-end loader.

A mature compost will be available in 12–24 months, de-

pending on various factors including the care with which

the organic material was blended to obtain optimum C:N

ratio; the supplementation of the material with additional

nutrients; the frequency of

aeration

(mixing and turning);

and the moisture content maintained.

Using the same site layout, the next step in mechaniza-

tion is the use of windrow turners. These turners can be

simple aeration machines or machines with the added ability

to shred material into smaller particles, while injecting sup-

plemental moisture and/or nutrients. Optimizing the capa-

bilities of such equipment requires close attention to temper-

ature variation within the windrows. Typically, the operator

will use a temperature probe to determine when the tempera-

ture falls in the range of 100°F (37–38°C). The equipment

will then fold the outer surface of the windrow inward,

replenishing air and moisture, and mixing in unconsumed

or supplemental nutrients. This promotes further decompo-

sition, which is identified by a gradual rise in temperature.

Sequential turning and mixing will continue until tempera-

tures are uniformly diminished to levels below 85°F (30°C).

This method produces a mature compost in four to eight

months.

Two more technologically advanced composting

methods are the in-vessel system and the forced-air system.

Both are capable of processing the bulk of all solid and

liquid municipal wastes. However, such flexibility imposes

substantial capital, technical, and operational requirements.

In forced air processing, organic material is placed on top

of a series of perforated pipes attached to fans which can

either blow air into, or draw air through the pile to control

its temperature, oxygen, and carbon dioxide needs. This

system is popular for its ability to process materials high in

moisture and/or nitrogen content, such as yard wastes. Time

to produce a mature compost is measured in days, depending

on the class of organic material processed. During in-vessel

processing, organic material is continuously fed into an in-

clined rotating cylinder, where the temperature, moisture,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Comprehensive Environmental Response

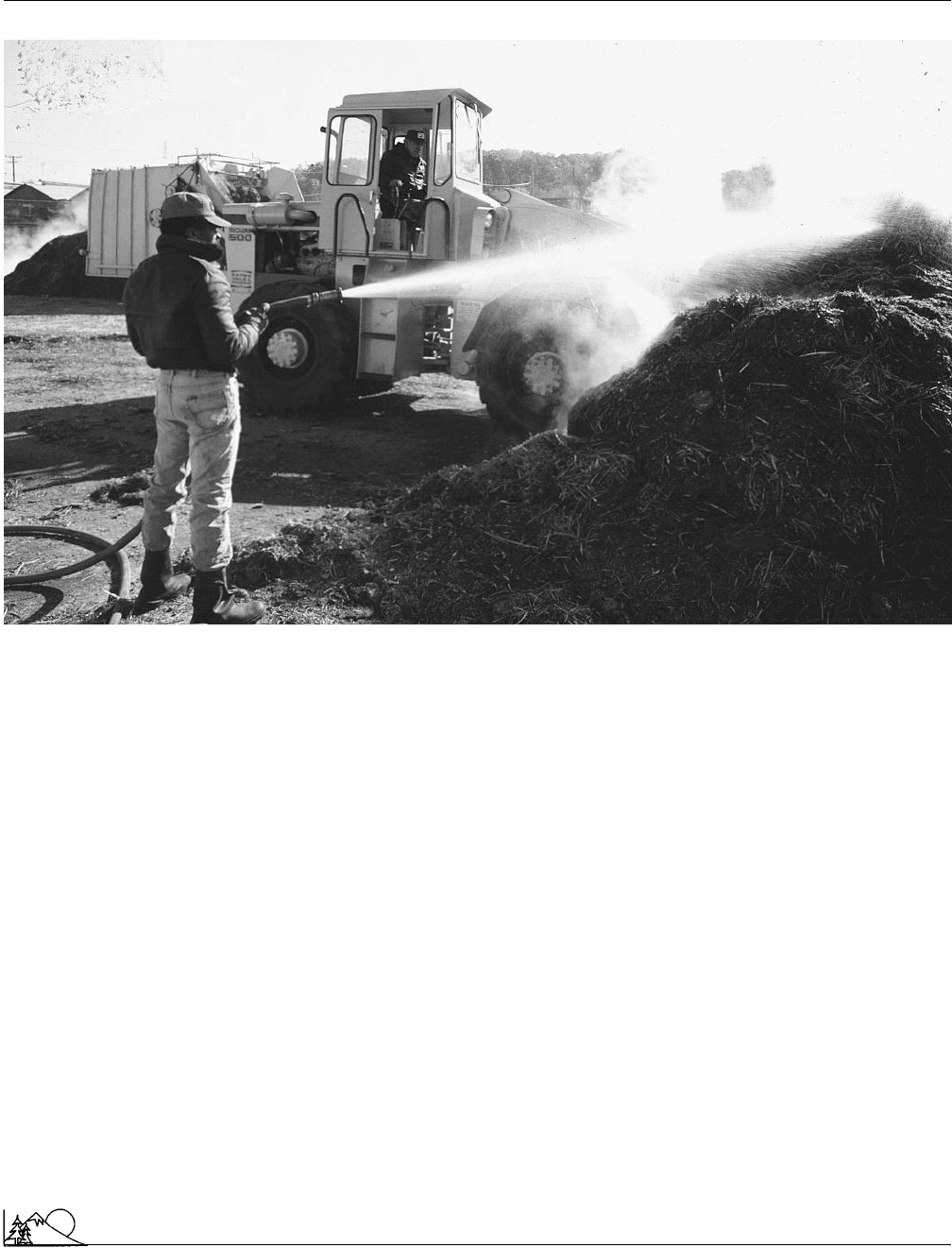

A man adds moisture to mushroom compost. (Photograph by Holt Confer. Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

and nutrient air and gas levels are closely controlled to achieve

degradation within 24–72 hours. The composted material

is then screened to remove foreign or inert materials such

as glass,

plastics

, and metals and is allowed to mature for

21 days.

[George M. Fell]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Appelhof, M. Worms Eat My Garbage. Kalamazoo, MI: Flower Press, 1982.

The Biocycle Guide to the Art and Science of Composting. Emmaus, PA: JG

Press, 1991.

The Biocycle Guide to Yard Waste Composting. Emmaus, PA: JG Press, 1989.

The Rodale Book of Composting. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Kovacic, D. A., et al. “Compost: Brown Gold or Toxic Trouble?” Environ-

mental Science and Technology 26 (January 1992): 38-41.

Lecard, M. “Urban Decay.” Sierra 76 (September-October 1991): 27-8.

299

Composting toilets

see

Toilets

Comprehensive Environmental

Response, Compensation, and

Liability Act (CERCLA)

In response to

hazardous waste

disasters such as

Love

Canal

, New York, in the 1970s, Congress passed the Com-

prehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and

Liability Act (CERCLA), better known as Superfund, in

1980. The law created a fund of $1.6 billion to be used to

clean up hazardous waste sites and hazardous waste spills

for a period of five years. The primary source of support for

the fund came from a tax on chemical feedstock producers;

general revenues supplied the rest of the money needed.

CERCLA is different from most environmental laws be-

cause it deals with past problems rather than trying to prevent

future

pollution

, and because the

Environmental Protec-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Comprehensive Environmental Response

tion Agency

(EPA), in addition to acting as a regulatory

agency, must clean up sites itself.

Throughout the decade before the creation of Su-

perfund, the public began to focus increasing attention on

hazardous wastes. During this period, an increased number

of cases involving such wastes contaminating drinking water,

streams, rivers, and even homes were reported. Citizens were

enraged by dangers posed by leaking landfills, illegal dump-

ing of hazardous wastes along roads or in vacant lots, and

explosions and fires at some facilities.

A strong catalyst for hazardous waste regulation was

the Love Canal episode near Niagara Falls, New York. In

the late 1970s, chemical wastes from an abandoned dump

were discovered in the basements of some homes. Studies

found significant health effects, including miscarriages and

low-weight newborns. Residents worried about increased

cancer

and birth defect rates. In the federal emergency

declaration, a school and 200 houses were condemned. The

combination of public concern and media coverage, together

with EPA interest, brought national attention to this issue.

Debate soon began over proper government response

to these problems. Industrial interests argued that a company

should not be liable for cleaning up past hazardous waste

dumps if it had not violated any law in disposing of the

wastes. The industry argued that general taxes, not industry-

specific taxes, should be used for the clean-up, and it sought

to limit the legal liability of manufacturers in regard to the

health effects of their hazardous wastes. Industrial companies

also pushed for one national regulatory program, rather than

a national program and several state programs to complicate

the situation.

When Congress began debating a Superfund program

in 1979, EPA officials argued that industry must pay the

bulk of the clean-up costs. They based this argument on

the philosophy that the polluter should pay, and also the

pragmatic reasoning that Congress could not be relied on

to continue appropriating the funds needed for such an

expensive and lengthy program. The Senate focused on a

comprehensive bill that included provisions for liability and

victims’ compensation

, but these were dropped in order

to secure passage of the program through the House. The

act was signed by President Carter in December 1980.

Under the law, the EPA determines the most danger-

ous hazardous waste sites, based on characteristics like toxic-

ity of wastes and risk of human exposure, and places them

on the

National Priorities List

(NPL), which determines

priorities for EPA efforts. The EPA has the authority to

either force those responsible for the site to clean it up, or

clean up the site itself with the Superfund money and then

seek to have the fund reimbursed through court action

against the responsible parties. If more than one company

had dumped wastes at a site, the agency is able to hold one

300

party responsible for all clean-up costs. It is then up to that

party to recover its costs from the other responsible parties.

If those identified as responsible by the EPA deny their

responsibility in court and lose, they are liable for treble

damages. Removal actions, emergency clean-ups, or actions

costing less than $2 million and lasting less than a year, can

be undertaken by the EPA for any site. For federal hazardous

waste sites, the clean-up must be paid for through the appro-

priation process rather than through Superfund. States are

required to contribute 10 to 50 percent of the cost of clean-

ups within their boundaries; they are also responsible for all

operation and maintenance costs once the job is finished.

The EPA can also delegate lead clean-up authority to the

states.

Major amendments to CERCLA were passed in 1986.

As the scope of the problem grew, Congress re-authorized

the Superfund through 1991 and increased its size to $8.5

billion. Plans indicated that the enlarged Superfund would

be financed by taxes on

petroleum

, feedstock

chemicals

,

corporate income, general revenue, interest from money in

the fund, and money recovered from companies responsible

for earlier clean-ups. The amendments required several areas

of compliance: 1) The clean-ups must meet the applicable

state and federal environmental standards; 2) The EPA must

begin clean-up on at least 375 sites by 1991; 3) Negotiated

settlements for clean-ups are preferred to court litigation;

4) Emergency procedures and community

right-to-know

standards, are required in areas with hazardous waste facili-

ties (largely in response to the

Bhopal, India

toxic gas disas-

ter); and 5) Federal agencies must comply with Superfund

Amendments and begin the clean-up of federal facilities and

sites. The 1991 Superfund Amendments and Reauthoriza-

tion Act authorized a four-year extension of the taxes that

financed Superfund, but the law was not changed signifi-

cantly.

As of August 1990, 33,000 sites were listed as being

potentially hazardous, 1,082 sites were on the NPL, and

over 100 sites were proposed by the EPA to be added to the

list. Of the sites that required preliminary EPA investigation,

over 90% had been examined, but actual clean-up has been

rather slow. In mid-1990, clean-up had been completed at

only 54 NPL sites. However, funding had been approved

for planning studies at over 1,000 sites, design work at over

400 sites, and remedial work at over 280 sites. Removal

actions by the EPA or responsible parties had taken place

at over 1,500 sites, most of which were not on the NPL.

Studies of Superfund implementation have been quite

critical. Reports by Congressional committees, the General

Accounting Office, and the Office of Technology Assess-

ment (OTA) concluded that the EPA relied on temporary

rather than permanent treatment methods, took too long to

clean up sites because of poor management, too frequently

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Computer disposal

opted to use the Superfund for clean-ups rather than requir-

ing responsible parties to pay, and often lacked the expertise

to oversee Superfund clean-up operations. In reality, early

implementation efforts of Superfund were hampered by un-

committed EPA officials, lack of financial and staff re-

sources, poor government coordination of policy objective,

and by the complexity of identifying and exacting payment

from responsible parties.

Another problem had been the amount of expensive

and time-consuming litigation involved in the act. In some

cases litigation costs to determine responsible parties and

recover clean-up costs has exceeded the cost of clean-up

itself. Between 1986 and 1988, the EPA only recovered 7%

of what it spent on clean-up from private parties.

Implementation of CERCLA has also been marked

by charges of corruption and political manipulation. Rita

Lavelle, who was in charge of the Superfund program at

EPA, resigned in 1983 amid charges that she was giving

unduly favorable treatment to industry. She was later con-

victed on perjury charges. Also in 1983, EPA Administrator

Anne Gorsuch Burford resigned, largely in response to the

difficulties of Superfund implementation.

Thus far, CERCLA has proved to be a more compli-

cated, costly, and time-consuming process than originally

envisioned. A 1988 Congressional report estimated that be-

tween $16.7 and $23.8 billion of federal money would be

needed to clean up the less than 1,000 sites then on the

NPL. A 1989 OTA report estimated the cost of the program

to be $500 billion in the long run, with as many as 10,000

sites eventually being placed on the NPL. See also Hazardous

material; Hazardous Materials Transportation Act; Hazard-

ous Substances Act; Hazardous waste site remediation; Haz-

ardous waste siting; Toxic substances

[Christopher McGrory Klyza]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Davis, C. E. The Politics of Hazardous Waste. New York: Prentice Hall, 1993.

Dower, R. C. “Hazardous Wastes.” In Public Policies for Environmental

Protection, edited by P. R. Portney. Washington, DC: Resources for the

Future, 1990.

Hays, S. P. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the

United States, 1955-1985. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Mazmanian, D., and D. Morell. Beyond Superfailure: America’s Toxics Policy

for the 1990s. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992.

Computer disposal

Because computer technology changes so quickly, the aver-

age computer sold in the United States in the early 2000s

becomes obsolete in only three years. Consumers were ex-

301

pected to retire about 50 million computers in 2002. One

government survey reported that 75% of all the computers

ever sold in the United States were stockpiled by 2001, not

disposed of even though their useful life is over. Computers

and other electronics account for about 220 million tons of

waste annually, according to the United States

Environmen-

tal Protection Agency

(EPA). Some older computers find

new users when they are passed on to nonprofit groups,

schools, or needy families. Some manufacturers arrange to

take back their out-of-date products. Approximately 10%

of outdated computers are recycled.

Computers contain a variety of materials, some of

them toxic. If computers are not recycled but disposed of in

landfills, valuable material is wasted, and

toxins

, particularly

lead

and

mercury

, may present a hazard to people and the

environment

. As many consumers are still storing two or

three older computers, the number of computers currently

in the

waste stream

is only a fraction of what it might be,

so computer disposal is a looming problem.

In the United States, the electronics industry,

conser-

vation

groups, and government organizations began work-

ing toward a satisfactory system of computer disposal in the

early 2000s. The Japanese government enacted a computer

recycling

law in 2001, and the

European Union

passed*

similar legislation, that will take effect in the middle of the

decade.

A typical computer consists of 30–40% plastic. The

plastic may be of several different types. Unlike the plastic

in food and beverage containers, which is usually given a

number to identify it and make recycling easier, plastic in

computers is unlabeled. A computer may contain over four

pounds of lead, as well as small amounts of the toxic metals

mercury and

cadmium

and traces of other metals including

gold, silver, steel,

aluminum

,

copper

, and

nickel

.

Recycling a computer is not a simple process, and is

also quite expensive. To recycle a computer it must be broken

into parts, and its usable materials separated. Plastic used

for computers can be recovered, reprocessed into pellets, and

sold for re-use. The metals also can be recovered, although

the process itself can generate dangerous waste. For instance,

gold can be stripped off computer chips with a wash of

hydrochloric

acid

. The acid must then be treated or stored

safely, or it can contaminate the environment.

Recycling is not an easy solution to the problem of

computer disposal. However, a few companies in the United

States have found electronics recycling to be a profitable

business. A report compiled by two West Coast environmen-

tal groups in 2002 found that up to 80% of computers

collected for recycling in California and other western states

ended up in

third world

countries, where parts were often

salvaged by low-paid workers. Not only were workers often

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Condensation nuclei

unprotected against toxic materials, but toxic waste was

dumped directly into lakes and streams, the report detailed.

Some government and conservation groups have sug-

gested that the computer industry try to reduce toxic waste

by redesigning its products. Labeling of

plastics

used would

simplify plastic recycling, as would phasing out some more

harmful materials and toxic fire-retardant coatings. Making

computers with parts that snap together instead of using

glue or metal nuts and bolts is another design consideration

that can make computers easier to recycle. A number of

major manufacturers, including Dell Computer and IBM,

began their own recycling programs in the early 2000s. A

coalition of industry, environmental, and government groups

called the National Electronics Product Stewardship Initia-

tive began meeting in 2001 to come up with national guide-

lines for computer disposal. The high cost of computer re-

cycling is expected to decline somewhat as the volume of

recycled machines rises. Because of the vast backlog of com-

puters in the United States waiting to be thrown out, it is

imperative to work out a system for safe disposal quickly.

[Angela Woodward]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Chappell, Jeff. “A Growing Problem.” Electronic News 48, no. 11 (March

11, 2002):1.

“Japan to Mandate Supplier Disposal of Home PCs". Computergram (July

2, 2001):N.

Schuessler, Heidi. “All Used Up and Someplace to Go.” New York Times

(November 23, 2001):G1, G9.

Toloken, Steve. “Group Wants Disposal Put on Computer Makers.” Plastics

News 13, no. 41 (December 10, 2001):7.

Truini, Joe. “Electronics Afterlife.” Waste News 6, no. 32 (January 8, 2001):1

Truini, Joe. “Electronic Waste Spurs California Action.” Waste News 7,

no. 5 (July 9, 2001):1.

Truini, Joe. “Electronic Waste Stream Comes to Fore.” Waste News 7, no.

17 (December 24, 2001):10.

Wade, Beth. “Life After Death for the Nation’s PCs.” American City and

County116, no. 4 (March 2001):22.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Electronic Industries Alliance, 2500 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, VA

USA 22201 (703) 907-7500, <http://www.eia.org>

National Electronics Product Stewardship Initiative, <http://eerc.ra.

utk.edu/clean/nepsi/index.htm>

Condensation nuclei

When air is cooled below its

dew point

, the water vapor it

contains tends to condense as droplets of water or tiny ice

crystals. Condensation may not occur, however, in the ab-

sence of tiny particles on which the water or ice can form.

These particles are known as condensation nuclei. The most

common types of condensation nuclei are crystals of salt,

302

particulate

matter formed by the

combustion

of

fossil

fuels

, and dust blown up from the earth’s surface. In the

process of cloud-seeding, scientists add tiny crystals of dry

ice or silver iodide as condensation nuclei to the

atmosphere

to promote cloud formation and precipitation.

Condor

see

California condor

Congenital malformations

see

Birth defects

Congo River and basin

The Congo River (also known as the Zaire River) is the

third longest river in the world, and the second longest in

Africa (after the Nile River in northeastern Africa). Its river

basin, one of the most humid in Africa, is also the largest

on that continent, covering over 12% of the total land area.

History

The equatorial region of Africa has been inhabited

since approximately the middle Stone Age. Late Stone Age

cultures flourished in the southern savannas after about

10,000

B.C.

and remained functional until the arrival of

Bantu-speaking peoples during the first millennium

B.C.

In

a series of migrations taking place from about 1,000

B.C.

to

the mid-first millennium

A.D.

, many Bantu-speakers dis-

persed from an area west of the Ubangi-Congo River swamp

across the forests and savannas of the region known as the

modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In the precolonial era, this region (modern-day Demo-

cratic Republic of the Congo) was dominated by three king-

doms: Kongo (late 1300s), the Loango (at its height in the

1600s), and Tio. Portugese navigator Diogo Cam was the

first European to sail up the mouth of the Congo in 1482.

After meeting with the rulers of the Kingdom of Kongo,

Cam negotiated intercontinental trade and commerce

agreements—including the slave trade—between Portugal

and the region. And a long history of colonialism began.

Over the centuries, the Congo River has inspired both

mystery and legend, from the explorations of Henry Morton

Stanley and David Livingstone in the 1870s, to Joseph Con-

rad, whose novel, Heart of Darkness transformed the river

into an eternal symbol of the “dark continent” of Africa.

Characteristics

The Congo River is approximately 2,720 mi long

(4,375 km), and its

drainage

basin consists of about 1.3

million mi

2

(3.6 million km

2

). The basin encompasses nearly

the entire Democratic Republic of the Congo (capital: Kins-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Congo River and basin

hasa), Republic of Congo (capital: Brazzaville), Central Afri-

can Republic, eastern Zambia, northern Angola, and parts

of Cameroon and Tanzania. The river headwaters emerge

at the junction of the Lualaba (the Congo’s largest tributary)

and Luvua rivers. The flow is generally to the northeast first,

then west, and finally south to its outlet into the Atlantic

Ocean at Banana, Republic of Congo.

The Congo basin comprises one of the most distinct

land depressions between the Sahara

desert

to its north,

and the Atlantic Ocean to its south and west. The river’s

tributaries flow down slopes varying from 900 to 1,500 ft

(274 to about 457 m) into the central depression forming

the basin. This depression extends for more than 1,200 mi

(about 1931 km) from the north to the south, from the

Congo Lake Chad

watershed

, to the plateaus of Angola.

From the east to west of the depression is another 1,200 mi

(about 1931 km)—from the Nile-Congo watershed to the

Atlantic Ocean. The width of the Congo River ranges from

3.5 mi (about 5.75 km) to 7 mi (about 11.3 km); and its

banks contain natural levees formed by

silt

deposits. During

floods, however, these levees overflow, widening the river.

With an average annual rainfall of 1,500 mm of rain

(about 60 in), about three-quarters returns to the

atmo-

sphere

by

evapotranspiration

; the rest is discharged into

the Atlantic. The river is divided into three main regions:

the upper Congo, with numerous tributaries, lakes, water-

falls, and rapids; the middle Congo; and, the lower Congo.

The middle Congo is characterized by its seven waterfalls,

collectively referred to as

Boyoma

(formerly Stanley) Falls.

It is below these falls that navigation on the river becomes

possible. The river has approximately 10,000 mi (about

16,000 km) of waterways, creating one of the main

trans-

portation

routes in Central Africa.

Economic and environmental impact

Due to its size and other key elements, the Congo

River and its basin are crucial to the ecological balance of

an entire continent. Although the Congo water

discharge

levels were unstable throughout the second half of the twen-

tieth century—the hydrologic balance of the river has pro-

vided some relief from the

drought

that has afflicted the

river basin. This relief occurs even with dramatic fluctuations

of rainfall throughout the various terrain through which the

river passes.

Researchers have suggested that

soil

geology plays a

key role in maintaining the river’s discharge

stability

despite

fluctuations in rainfall. The sandy soils of the Kouyou region,

for example, have a stabilizing effect in their ability to store

or disperse water.

In 1999, the World Commission on Water for the

twenty-first century, based in Paris and supported by the

World Bank

and the United Nations, found that the Congo

was one of the world’s cleanest rivers—in part due to the

303

lack of industrial development along its shores until that

time. However, the situation is changing.

The rapidly increasing human population threatens to

compromise the integrity of Congo basin ecosystems. Major

threats to the large tropical rainforests and savannas, as well

as to

wildlife

, come from the exploitation of

natural re-

sources

. Uncontrolled

hunting

and fishing,

deforestation

(which causes

sedimentation

and

erosion

near

logging

operations) for timber sale or agricultural purposes, un-

planned urban expansion (which increases the potential for

an increase in untreated sewage and other sources of

pollu-

tion

that could harm nearby freshwater systems), and unre-

strained extraction of oil and minerals are some of the major

economic and environmental issues confronting the region.

And these issues are expected to have a global impact as well.

Wildlife

According to the

World Wildlife Fund

, the Congo

River and its basin, also known as the “Congo River and

Flooded Forests ecoregion,” is home to the most diverse

and distinctive group of animals adapted to a large-river

environment

in all of tropical Africa.

The Congo river had no outlet to the ocean during

the Pliocene Age (5.4–2.4 million years ago) but was instead

a large lake. Eventually, the water broke through the rim of

the lake, emerging as a river that passed over rocks through

a series of rapids, then entered the Atlantic. Except for

the beginning and end of its course, the river is uniformly

elevated.

With more than 700 fish

species

, 500 of which are

endemic to the river, the Congo basin ranks second only to

the Amazon in its diversity of species. Nearly 80% of fish

species found in the Congo basin exist nowhere else in the

world. The various species live both in the river and its

attendant habitats—swamps, nearby lakes, and headwater

streams. They feed in a variety of ways: scouring the mud

at the river’s bottom; eating scales off of live fish; and eating

smaller fish. Certain fish have even adapted to the river’s

muddy waters. For example, some have reduced eye size, or

no eyes at all, yet easily maneuver through the swift current.

The Congo’s freshwater fish are a crucial protein source for

Central Africa’s population; yet the potential for over-fishing

near the urban areas along its banks threatens the available

supply.

There are also a wide variety of aquatic mammals—

such as unusual species of otters, shrews, and monkeys—

that are indigenous to the river basin. Rainforests cover

over 60% of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and

represents nearly 6% of the world’s remaining forested area,

and 50% of Africa’s remaining forests. Many of the world’s

endangered species

live near the river, including gorillas.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Coniferous forest

River traffic—war, power, and tourism

At the end of May 2001, the United Nations Security

Council announced that the Congo River would finally re-

open to commercial traffic after a more than two-year

blockage due to the war in the Democratic Republic of the

Congo. Because of the desperate state of roads throughout

the region—or the complete lack of roads—individuals, busi-

ness, and other agencies have relied primarily on river trans-

portation.

The river had been divided in two at the front line of

warring factions—the government forces and their foreign

allies on one side, and the rebels backed by Uganda and

Rwanda on the other. Massive starvation resulted from the

blockage, halting supplies from the United Nations and other

humanitarian aid agencies.

With the drought that was running rampant through

the early years of the twenty-first century, and those droughts

that were anticipated in some areas of southern Africa, distri-

bution of water remains a major challenge. In the fall of

2000, the Southern African Development Community, a

group of Congolese business people, began to look to the

Congo River for a solution to these water problems.

These developers launched a plan to pump water from

the Congo River, by building two long-distance pipelines

(known as the Solomon pipelines)— one across the mouth

of the Congo River to Walvis Bay in Namibia, 621 mi (about

1,000 km) away; the other, running through civil war zones.

They would supply water to the Middle East by way of Port

Sudan, a distance of nearly 1,242 mi (about 2,000 km).

The company initiating the plan, Westrac, claimed

that the project would create hundreds of jobs, provide for

the building of hospitals along the route, and lay fiber-

optic communications links as well—thereby boosting the

economy of the region and enhancing the lives of the native

population. Detractors of the plan countered that the plan

would be cost-prohibitive and hazardous to the environment.

According to the California-based International Rivers Net-

work, it was “premature to investigate such a complex plan

when simpler and cheaper solutions haven’t been fully ex-

plored,” as reported by Radio Netherlands.

With political issues far from resolved as of 2002, and

the potential for widespread pollution if industry and the

population exploits the resources of the river, future plans

could remain unresolved for decades to come. Yet, Salomon

Banamuherem, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s

minister of tourism, hoped that the project would tap into

another great natural resource of the country and its river—

tourism. In its entire history, even in times of peace, the

country—Africa’s third largest country—has attracted no

more than100,000 visitors per year.

Despite unresolved political and economic issues, pro-

tecting the biodiverse resources and

ecosystem

of the

304

Congo River and basin is perhaps the most important and

challenging task facing this region in the future.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Fish, Bruce and Becky-Durost Fish.Congo: Exploration, Reform, and a Brutal

Legacy.Philadelphia: Chelsea House Pub., 2001.

Tayler, Jeffrey.Facing the Congo. St. Paul: Ruminator Books, 2000.

The Congo Basin: Human and Natural Resourcs.Amsterdam: Netherlands

Institute for IUCN, 1998.

O

THER

Congo-pages. Congo River Basin. June 3, 2002 [cited July 2, 2002]. <http://

www.congo-pages.org/>

Eureka Alert. Congo River Basin: Geology and soil type influence impact.

January 11, 2002 [cited July 1, 2002].<http://www.eurekalert.org/>

Johnson, David. Africana. “Congo River called one of the world’s cleanest.”

December 3, 1999 [cited June 2002]. <http://www.africana.com/>

O

RGANIZATIONS

World Wildlife Fund, 1250 24th St. N.W, P.O. Box 97180., Washington,

DC USA 20090-7180 Fax: 202-293-9211, Toll Free: 1-800-CALL-

WWF, , http://www.worldwildlife.org

Coniferous forest

Coniferous forests contain trees with cones and generally

evergreen needle or scale-shaped leaves. Important genera

in the northern hemisphere include pines (Pinus), spruces

(Picea), firs (Abies),

redwoods

(Sequoia), Douglas firs (Pseu-

dotsuga), and larches (Larix). Different genera dominate the

conifer forests of the southern hemisphere. Conifer forests

occupy regions with cool-moist to very cold winters and

cool to hot summers. Many conifer forests originated as

plantations of

species

from other continents. Among conifer

formations in North America are the slow-growing circum-

polar

taiga

(boreal), the subalpine-montane, the southern

pine, and the Pacific Coast temperate

rain forest

. Soft-

woods, another name for conifers, are used for lumber, pan-

els, and paper.

Conservation

The philosophy or policy that

natural resources

should be

used cautiously and rationally so that they will remain avail-

able for

future generations

. Widespread and organized

conservation movements, dedicated to preventing uncon-

trolled and irresponsible exploitation of forests, lands,

wild-

life

, and

water resources

, first developed in the United

States in the last decades of the nineteenth century. This

was a time at which accelerating settlement and resource

depletion made conservationist policies appealing both to a

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Conservation

large portion of the public and to government leaders. Since

then, international conservationist efforts, including work of

the United Nations, have been responsible for monitoring

natural resource use, setting up

nature

preserves, and con-

trolling environmental destruction on both public and private

lands around the world.

The name most often associated with the United

States’ early conservation movement is that of

Gifford Pin-

chot

, the first head of the U.S.

Forest Service

. A populist

who fervently believed that the best use of nature was to

improve the life of the common citizen, Pinchot brought

scientific management methods to the Forest Service. He

also brought a strongly utilitarian philosophy, which contin-

ues to prevail in the Forest Service. Beginning as an advisor

to

Theodore Roosevelt

, himself an ardent conservationist,

Pinchot had extensive influence in Washington and helped

to steer conservation policies from the turn of the century to

the 1940s. Pinchot had a number of important predecessors,

however, in the development of American conservation.

Among these was George Perkins Marsh, a Vermont forester

and geographer whose 1864 publication, Man and Nature,

is widely held as the wellspring of American environmental

thought. Also influential was the work of John Wesley Pow-

ell, Clarence King, and other explorers and surveyors who,

after the Civil War, set out across the continent to assess

and catalog the country’s physical and biological resources

and their potential for development and settlement.

Conservation, as conceived by Pinchot, Powell, and

Roosevelt was about using, not setting aside, natural re-

sources. In their emphasis on wise resource use, these early

conservationists were philosophically divided from the early

preservationists, who argued that parts of the American

wil-

derness

should be preserved for their aesthetic value and

for the survival of wildlife, not simply as a storehouse of

useful commodities. Preservationists, led by the eloquent

writer and champion of Yosemite Valley,

John Muir

, bitterly

opposed the idea that the best vision for the nation’s forests

was that of an agricultural crop, developed to produce only

useful

species

and products. Pinchot, however, insisted that

“The object of [conservationist] forest policy is not to pre-

serve the forests because they are beautiful...or because they

are refuges for the wild creatures of the wilderness...but the

making of prosperous homes...Every other consideration is

secondary.” Because of its more moderate and politically

palatable stance, conservation became, by the turn of the

century, the more popular position. By 1905 conservation

had become a blanket term for nearly all defense of the

environment

; the earlier distinction was lost until it began

to re-emerge in the 1960s as “environmentalists” began once

again to object to conservation’s anthropocentric (human-

centered) emphasis. More recently deep ecologists and biore-

gionalists have likewise departed from mainstream conserva-

305

tion, arguing that other species have intrinsic rights to exist

outside of human interests.

Several factors led conservationist ideas to develop and

spread when they did. By the end of the nineteenth century

European settlement had reached across the entire North

American continent. The census of 1890 declared the Amer-

ican frontier closed, a blow to the American myth of the

virgin continent. Even more important, loggers, miners, set-

tlers, and livestock herders were laying waste to the nation’s

forests,

grasslands

, and mountains from New York to Cali-

fornia. The accelerating, and often highly wasteful, commer-

cial exploitation of natural resources went almost completely

unchecked as political corruption and the economic power

of timber and lumber barons made regulation impossible.

At the same time, the disappearance of American wildlife

was starkly obvious. Within a generation the legendary flocks

of passenger pigeons disappeared entirely, many of them

shot for pig feed while they roosted. Millions of

bison

were

slaughtered by market hunters for their skins and tongues

or by sportsmen shooting from passing trains. Natural land-

marks were equally threatened—Niagara Falls nearly lost its

water to hydropower development, and California’s Sequoia

groves and Yosemite Valley were threatened by

logging

and

grazing.

At the same time, post-Civil War scientific surveys

were crossing the continent, identifying wildlife and forest

resources. As a consequence of this data gathering, evidence

became available to document the depletion of the conti-

nent’s resources, which had long been assumed inexhaustible.

Travellers and writers, including John Muir, Theodore Roo-

sevelt, and Gifford Pinchot, had the opportunity to witness

the alarming destruction and to raise public awareness and

concern. Meanwhile an increasing proportion of the popula-

tion had come to live in cities. These urbanites worked in

occupations not directly dependent upon resource exploita-

tion, and they were sympathetic to the idea of preserving

public lands for recreational interests. From the beginning

this urban population provided much of the support for the

conservation movement.

As a scientific, humanistic, and progressive policy,

conservation has led to a great variety of projects. The devel-

opment of a professionally trained forest service to maintain

national forests has limited the uncontrolled “tree mining”

practiced by logging and railroad companies of the nine-

teenth century. Conservation-minded presidents and admin-

istrators have set aside millions of acres

public land

for

national forests, parks, and other uses for the benefit of the

public. A corps of professionally trained game managers and

wildlife managers has developed to maintain game birds,

fish, and mammals for public

recreation

on federal lands.

(For much of its history, federal game conservation has

involved extensive predator elimination programs, however

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Conservation biology

several decades of protest have led to more ecological ap-

proaches to game management in recent decades.) During

the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, conservation

projects included such economic development projects as

the

Tennessee Valley Authority

(TVA), which dammed

the Tennessee River for flood control and electricity genera-

tion. The Civilian Conservation Corps developed roads,

built structures, and worked on

erosion

control projects for

the public good. During this time the

Soil Conservation

Service

was also set up to advise farmers in maintaining

and developing their farmland.

At the same time, voluntary citizen conservation orga-

nizations have done extensive work to develop and maintain

natural resources. The

Izaak Walton League

,

Ducks Un-

limited

, and scores of local gun clubs and fishing groups have

set up game sanctuaries, preserved

wetlands

, campaigned to

control

water pollution

, and released young game birds

and fish. Other organizations with less directly utilitarian

objectives also worked in the name of conservation: the

National Audubon Society

, the

Sierra Club

, the

Wilder-

ness Society

,

The Nature Conservancy

, and many other

groups formed between 1895 and 1955 for the purpose of

collective work and lobbying in defense of nature and

wildlife.

An important aspect of conservation’s growth has been

the development of professional schools of forestry, game

management, and

wildlife management

. When Gifford

Pinchot began to study forestry, Yale had only meager re-

sources and he gained the better part of his education at a

French school of

forest management

in Nancy, France.

Several decades later the Yale School of Forestry (financed

largely by the wealthy Pinchot family) was able to produce

such well-trained professionals as

Aldo Leopold

, who went

on to develop the United States’ first professional school of

game management at the University of Wisconsin.

From the beginning, American conservation ideas, in-

formed by the science of

ecology

and the practice of resource

management on public lands, spread to other countries and

regions. It is in recent decades, however, that the rhetoric

of conservation has taken a prominent role in international

development and affairs. The most visible international con-

servation organizations today is the United Nations Environ-

ment Program (UNEP), the Food and Agriculture Organi-

zation of the United Nations (FAO), and the

World

Wildlife Fund

. In 1980 the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) pub-

lished a document entitled the World Conservation Strategy,

dedicated to helping individual states, and especially devel-

oping countries, plan for the maintenance and protection of

soil

, water, forests, and wildlife. A continuation and update

of this theme appeared in 1987 with the publication of the

UN World Commission on Environment and Develop-

306

ment’s paper,

Our Common Future

. The idea of sustainable

development, a goal of ecologically balanced, conservation-

oriented economic development, was introduced in this 1987

paper and has since become a dominant ideal in international

development programs of the 1990s.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Fox, S. John Muir and His Legacy: the American Conservation Movement.

Boston: Little, Brown, 1981.

Pinchot, G. Breaking New Ground. Washington, DC: Island Press, 1987

(originally 1947).

Marsh, G. P. Man and Nature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965

(originally 1864).

Meine, C. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Madison, WI: University of

Wisconsin Press, 1988.

Conservation biology

Conservation

biology is concerned with the application of

ecological and biological science to the conservation and

protection of Earth’s

biodiversity

. Conservation biology is

a relatively recent field of scientific activity, having emerged

during the past several decades in response to the accelerating

biodiversity crisis. Conservation biology represents an inte-

gration of theory, basic and applied research, and broader

educational goals. It includes much of

ecology

but extends

it with social sciences, policy, and management.

The most important cause of the biodiversity crisis is

the disturbance of natural habitats, particularly through the

conversion of tropical forests into agricultural habitats. Bio-

diversity is also greatly threatened by the excessive

hunting

of certain

species

, by commercial forestry, by

climate

change, and by other stressors associated with human activi-

ties, such as air and

water pollution

. A central goal of

conservation biology is to discover ways of avoiding or re-

pairing the damages that human influences are causing to

biodiversity. Important considerations include the develop-

ment of science-based methods for conserving endangered

populations of species on larger landscapes (or seascapes, in

marine environments), and of designing systems of protected

areas where natural ecosystems and indigenous species can

be conserved.

Biodiversity and its importance

Biodiversity can be defined as the total richness of

biological variation. The scope of biodiversity ranges from

the genetic variation of individuals within and among popu-

lations of species, to the richness of species that co-occur

in ecological communities. Some ecologists also consider