Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Commercial fishing

comparable to that of humans and adults typically grow to

500 lb (227 kg). The success of a 1982 ban on fishing the

black sea bass off the coast of California became evident

early this century when significant numbers of these young

fish, already weighing as much as 200 lb (91 kg), appeared

off the shores of Santa Barbara. Yet, full replenishment of

the population remains years away.

Environmental problems also

plague

commercial

fishing. Near-shore

pollution

has altered ecosystems, taking

a heavy toll on all populations of fish and shellfish, not

only those valued commercially. The collective actions of

commercial fishermen also create some major environmental

problems. The world’s commercial fishermen annually catch

and then discard about 20 billion lb (9 billion kg) of non-

target species of sea life. In addition to fish and shellfish,

each year about one million seabirds are caught and killed

in fishermen’s nets. On average more than 6,000

seals and

sea lions

, about 20,000

dolphins

and other aquatic mam-

mals, and thousands of

sea turtles

meet the same fate. It

is estimated that the amount of fish discarded annually is

about 25% of the reported catch, or about 20 million metric

tons per year. Ecologically, two major problems arise from

this massive disposal of organisms. One is the disruption

of predator-prey ratios, and the other is the addition of a

tremendous overload of

organic waste

to be dealt with in

this

ecosystem

.

In 2001, a $1.6 billion gas pipeline that was proposed

to be routed through neighboring waters from Nova Scotia

to New Jersey, to be implemented as early as 2005, posed

a new environmental threat to the Georges Bank area. Envi-

ronmentalists, meanwhile, have lobbied the United States

government to establish a marine

habitat

protection desig-

nation similar to

wilderness

areas and natural parks on

land, to provide for the preservation of reefs, marine life,

and underwater vegetation. In 2001, less than 1% of

water

resources

worldwide had the protection of formal legisla-

tion to prevent exploitation.

Habitat destruction is serious environmental concern.

Fish and other aquatic

wildlife

rely on the existence of high

quality habitat for their survival, and loss of habitat is one

of the most pressing environmental threats to shorelines,

wetlands

, and other aquatic habitats. Approaches to the

protection of

essential fish habitat

include efforts to

strengthen and vigorously enforce the

Clean Water Act

and

other protective legislation for aquatic habitats, to develop

and implement restoration plans for target regions, to make

improved policy decisions based on technical knowledge

about shoreline habitats, and to better educate the public

on the importance of protecting and restoring habitat. A

relatively new approach to habitat recovery is the habitat

conservation

plan (HCP), in which a multi-species ecosys-

tem approach to habitat management is preferred over a

287

reactive species-by-species plan. Strategies for fish recovery

are complex, and, instead of numbers of fish of a given

species, the HCP uses quality of habitat to measure the

success of restoration and conservation efforts. Long-term

situations such as the restoration of black sea bass serve to

re-emphasize the importance of resisting the temptation to

manage overfishing of single species while failing to address

the survival of the ecosystem as a whole.

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and

Management Act was passed in 1976 to regulate fisheries

resources and fishing activities in Federal waters, those wa-

ters extending to the 200-mi (322-km) limit. The act recog-

nizes that commercial fishing contributes to the food supply

and is a major source of employment, contributing signifi-

cantly to the economy of the Nation. However, it also recog-

nizes that overfishing and habitat loss has led to the decline

of certain species of fish to the point where their survival is

threatened, resulting in a diminished capacity to support

existing fishing levels. Further, international fishery

agreements have not been effective in ending or preventing

overfishing. Fishery resources are limited but renewable and

can be conserved and maintained to continue to provide good

yields. Also, the act supports the development of underused

fisheries, such as bottom-dwelling fish near Alaska.

Another resource to sustain increases in seafood con-

sumption is

aquaculture

, where commercial food-fish spe-

cies are grown on fish farms. It is estimated that the amount

of farm-raised fish has doubled in the past decade and that

about 20% of the fish consumed worldwide is raised in

captivity.

In the United States, as well as other nations, the

commercial fisheries industry faces potential collapse. Severe

restrictions and tight controls imposed by the international

community may be the only means of salvaging even a por-

tion of this valuable industry. It will be necessary for partner-

ships to be forged between scientists, fisherman, and the

regulatory community to develop and implement measures

toward maintaining a sustainable fishery.

[Eugene C Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bricklemyer, E., S. Iudicello, and H. Hartmann. “Discarded Catch in U.S.

Commercial Marine Fisheries.” In Audubon Wildlife Report 1990-1991. San

Diego: Academic Press, 1990.

Weber, M. “Federal Marine Fisheries Management.” In Audubon Wildlife

Report 1986. San Diego: Academic Press, 1986.

P

ERIODICALS

Lawren, B. “Net Loss.” National Wildlife 30 (1992): 46-53.

Associated Press, February 19, 2001.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Commission for Environmental Cooperation

O

THER

Dudley-Cash, William A. “ Aquaculture has been the world’s fastest grow-

ing food production system.” Factoryfarming.com: Factory Seafood Production

June 29, 1998 [cited July 9, 2002] < http://www.factoryfarming.com/

fish.html>.

Guinan, John A. and Ralph E. Curtis “A Century Of Conservation.”

NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service, April 1971 [cited July 9, 2002]

<http://www.nefsc.nmfs.gov/library/history/century.html>.

Loftas, Tony “Not enough fish in the sea.” Our Planet 7.6 April 1996

[cited July 9, 2002] <http://www.ourplanet.com/imgversn/76/loftas.html>.

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, Public Law

94-265 (as amended through October 11, 1996). [cited July 9, 2002] <http://

www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/magact/>.

Vogel, William and Lorin Hicks “Multi-species HCPs:Experiments with

the Ecosystem Approach.” Endangered Species Bulletin July/August 2000,

Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 20-22 [cited July 9, 2002] <http://endangered.fws.gov/

esb/2000/07-08/20-22.pdf>.

Commingled recyclables

see

Recycling

Commission for Environmental

Cooperation

The Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) is

a trilateral international commission established by Canada,

Mexico, and the United States in 1994 to address trans-

boundary environmental concerns in North America. The

original impetus behind the CEC was the perception of

inadequacies in the environmental provisions of the

North

American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA). A supple-

mentary treaty, the North American Agreement for Envi-

ronmental Cooperation (NAAEC) was negotiated to rem-

edy these inadequacies, and it is from the NAAEC that the

CEC derives its formal mandate.

The general goals set forth by the NAAEC are to

protect, conserve, and improve the

environment

for the

benefit of present and

future generations

. More specifi-

cally, the three NAFTA signatories agreed to a core set of

actions and principles with regard to environmental concerns

related to trade policy. These actions and principles include

regular reporting on the state of the environment, effective

and consistent enforcement of

environmental law

, facilita-

tion of access to environmental information, the ongoing

improvement of environmental laws and regulations, and

promotion of the use of tax incentives and various other

economic instruments to achieve environmental goals.

The CEC is to function as a forum for the NAFTA

partners to identify and articulate mutual interests and priori-

ties, and to develop strategies for the pursuit or implementa-

tion of these interests and priorities. The NAAEC further

specifies the following priorities: identification of appro-

priate limits for specific pollutants; the protection of endan-

288

gered and threatened

species

; the protection and

conserva-

tion

of wild

flora

and

fauna

and their

habitat

; the

development of new approaches to environmental compli-

ance and enforcement; strategies for addressing environmen-

tal issues that have impacts across international borders; the

support of training and education in the environmental field;

and promotion of greater public awareness of North Ameri-

can environmental issues. Central to the CEC’s mission is

the facilitation of dialogue among the NAFTA partners in

order to prevent and solve trade and environmental disputes.

The governing body of the CEC is a Council of Minis-

ters consisting of the environment ministers (or equivalent)

from each country. The executive arm of the Commission

is a Secretariat located in Montreal, consisting of a staff of

about 30 members and headed by an Executive Director.

The staff is drawn from all three countries and provides

technical and administrative support to the Council of Min-

isters and to committees and groups established by the

Council.

Technical and scientific advice is also provided to the

Council of Ministers by a Joint Public Advisory Committee

consisting of five members from each country appointed by

the respective governments. This Committee may, on its

own initiative, advise the Council on any matter within the

scope of the NAAEC, including the annual program and

budget. As a reflection of the CEC’s professed commitment

to participation by citizens throughout North America, the

Committee is intended to represent a wide cross-section of

knowledgeable citizens committed to environmental con-

cerns who are willing to volunteer their time in the public

interest. The CEC also accepts direct input from any citizen

or non-governmental organization who believes that a

NAFTA partner is failing to enforce effectively an existing

environmental law.

The NAAEC also contains provisions for dispute res-

olution in cases in which a NAFTA signatory alleges that

another NAFTA partner has persistently failed to enforce an

existing environmental law, causing specific environmental

damage or trade disadvantages to the claimant. These provi-

sions may be invoked when a lack of effective enforcement

materially affects goods or services being traded between the

NAFTA countries. If the dispute is not resolved through

bilateral consultation, the complaining party may then re-

quest a special session of the CEC’s Council of Ministers.

If the Council is likewise unable to resolve the dispute,

provisions exist for choosing an Arbitral Panel. Failure to

implement the recommendations of the Arbitral Panel sub-

jects the offending party to a monetary enforcement assess-

ment. Failure to pay this assessment may lead to suspension

of free trade benefits.

The Council is also instructed to develop recommen-

dations on access to courts (and rights and remedies before

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Barry Commoner

courts and administrative agencies) for persons in one coun-

try’s territory who have suffered or are likely to suffer damage

or injury caused by

pollution

originating in the territory of

one of the other countries. In 2002, the Council published

a five year study which stated that 3.4 million tonnes of

toxins

were produced in North America.

The CEC has been subject to some of the same criti-

cisms leveled at the environmental provisions of NAFTA,

particularly that it serves as a kind of environmental window-

dressing for a trade agreement that is generally harmful to

the environment. The CEC’s mandate for conflict resolution

is primarily oriented towards consistent enforcement of ex-

isting environmental law in the three countries. This law is

by no means uniform. By upholding the principles of free

trade, and providing penalties for infringements of free trade,

NAFTA establishes an environment in which private com-

panies have an economic incentive, other considerations be-

ing equal, to locate production where environmental laws

are weakest and the costs of compliance are therefore lowest.

Countries with stricter environmental regulations face penal-

ties for attempting to protect domestic industries from such

comparative disadvantages.

[Lawrence J. Biskowski]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

Kass, S. L. “First Cases Before New NAFTA Forum Suggest Its Power

Will Increase.” National Law Journal 18/41 (10 June 1996): C5, C7.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 393, rue St-Jacques Ouest,

Bureau 200, Montre

´

al, Que

´

becCanada H2Y 1N9 (514) 350-4300, Fax:

(514) 350-4314, Email: info@ccemtl.org, <http://www.cec.org>

Barry Commoner (1917 – )

American biologist, environmental scientist, author, and

social activist

Born to Russian immigrant parents, Commoner earned a

doctorate in biology from Harvard in 1941. As a biologist,

he is known for his work with free radicals—chemicals like

chlorofluorocarbons

, which are suspected culprits in

ozone layer depletion

. Commoner led a fairly academic

life at first, with research posts at various universities, but

rose to some prominence in the late 1950s, when he and

others protested atmospheric testing of

nuclear weapons

.

He earned a national reputation in the 1960s with books,

articles, and speeches on a wide range of environmental

concerns, including

pollution

,

alternative energy sources

,

and population. His latest book, Making Peace with the

Planet, was published in 1990. Commoner’s other works

include Science and Survival (1967), The Closing Circle

289

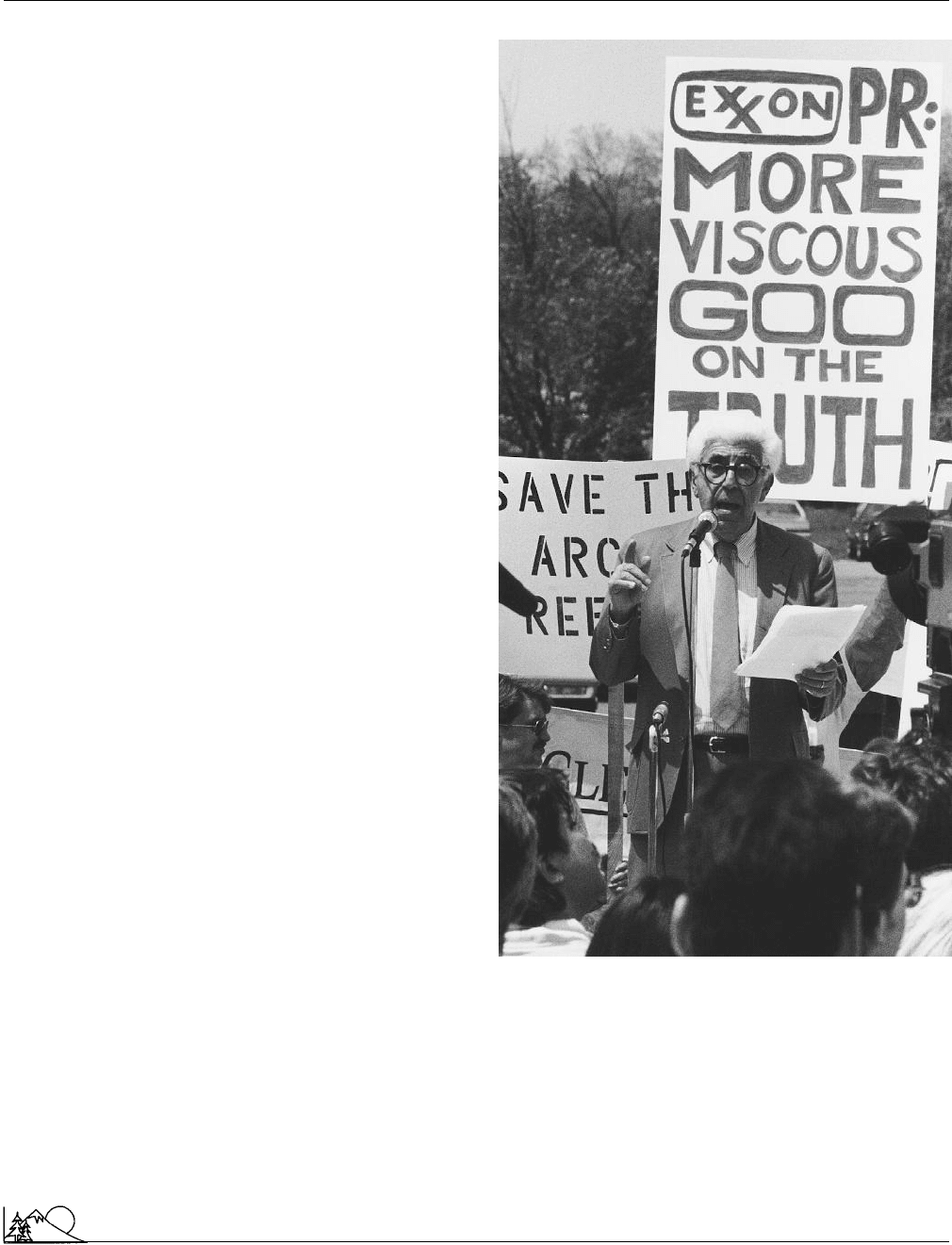

Barry Commoner speakingto a group of pro-

testers gathered outside a New Jersey hotel

where Exxon stockholders met in 1989. (Corbis-

Bettmann. Reproduced by permission.)

(1971), Energy and Human Welfare (1975), The Poverty of

Power (1976), and The Politics of Energy (1979).

Commoner believes that post-World War II industrial

methods, with their reliance on nonrenewable

fossil fuels

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Communicable diseases

are the root cause of modern environmental pollution. When

combined with a myopic view of the bottom line, he states,

the devastation is complete: “At present, economic consider-

ations—in particular, the private desire for maximizing

short-term profits—govern the choice of productive technol-

ogy, which in turn determines its environmental impact,

generally for the worse.” The petrochemicals industry re-

ceives the largest share of Commoner’s criticism. He refers

to “the

petrochemical

industry’s toxic invasion of the bio-

sphere” and states flatly that “the petrochemical industry is

inherently inimical to environmental quality.”

Almost as distressing as environmental pollution is

our inability to clean it up. Commoner rejects attempts at

environmental regulation as pointless. Far better, he says,

to not produce the toxin in the first place. “When a pollutant

is attacked at the point of origin—in the production process

that generates it—the pollutant can be eliminated; once it

is produced, it is too late. This is the simple but powerful

lesson of the two decades of intense but largely futile effort

to improve the quality of the environment.”

Commoner offers radical, sweeping solutions for social

and ecological ills. The most urgent of these is a

renewable

energy

source, primarily photovoltaic cells powered by

so-

lar energy

. These would not only decentralize

electric utili-

ties

(another target of Commoner’s), but would use sunlight

to fuel almost any energy need, including smaller, lighter,

battery-powered cars. To ease the transition from fossil fuels

to solar power, he proposes

methane

,

cogeneration

(which

produces electricity from waste heat), and an organic agricul-

ture system that would “produce enough

ethanol

to replace

about 20 percent of the national demand for

gasoline

with-

out reducing the overall supply of food or significantly affect-

ing its price.”

Commoner makes few compromises, and his environ-

mental zeal has made him a crusader for social causes as

well. Eliminating

Third World

debt, he argues, would

improve life in impoverished countries and end the spiral

of economic desperation that drives countries to overpopu-

lation. “This [debt forgiveness] should be regarded not as

a magnanimous gesture but as partial reparations for the

damage inflicted...by the former colonial empires...[T]he

cause of poverty is the grossly unequal distribution of the

world’s wealth...we must redistribute that wealth, among

nations and within them.”

In 1980, Commoner made a bid for the presidency

on the Citizen’s Party ticket, a short-lived political attempt

to combine environmental and Socialist agendas. Since 1981

he has been the director of the Center for the Biology of

Natural Systems at Queens College in New York City.

[Muthena Naseri and Amy Strumolo]

290

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Commoner, B. The Closing Circle. New York: Knopf, 1971.

———. Making Peace With the Planet. New York: New Press, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Commoner, B. “Ending the War Against Earth.” The Nation 250 (30 April

1990): 589–90.

———. “The Failure of the Environmental Effort.” Current History 91

(April 1992): 176–81.

Stone, P. “The Ploughboy Interview.” Mother Earth News (March–April

1990): 116–26.

Communicable diseases

A communicable disease is any disease that can be transmit-

ted from one organism to another. Agents that cause com-

municable diseases, called pathogens, are easily spread by

direct or indirect contact. These pathogens include viruses,

bacteria,

fungi

, and

parasites

. Some pathogens make

tox-

ins

that harm the body’s organs. Others actually destroy

cells. Some can impair the body’s natural immune system,

and opportunistic organisms set up secondary infections that

cause serious illness or death. Once the pathogens have

multiplied inside the body, signs of illness may or may not

appear. The human body is adept at destroying most patho-

gens, but the pathogens may still multiply and spread.

The pathogens responsible for some communicable

diseases have been known since the mid-1800s, although

they have existed for a much longer period of time. European

explorers brought highly contagious diseases such as small-

pox, measles, typhus and scarlet fever to the New World,

to which Native Americans had never been exposed. These

new diseases killed 50–90% of the native population. Native

populations in many areas of the Caribbean were totally

eliminated.

In some areas of the world,

contaminated soil

or

water incubate the pathogens of communicable diseases, and

contact with those agents will cause diseases to spread. In the

1800s, when Robert Koch discovered the

anthrax

bacillus

(Bacillus anthracis),

cholera

bacillus (Vibrio cholerae), and

tubercle bacillus (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), his work ush-

ered in a new era of public

sanitation

by showing how

water-borne epidemics, such as cholera and typhoid, could

be controlled by water

filtration

.

Malaria

, another communicable disease, was respon-

sible for the decline of many ancient civilizations; for centu-

ries, it devitalized vast populations. With the discoveries in

the late 1800s of protozoan malarial parasites in human

blood, and the discovery of its carrier, the Anopheles mos-

quito, malaria could be combatted by systematic destruction

of the mosquitos and their breeding grounds, by the use of

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Community ecology

barriers between mosquitos and humans such as window

screens and mosquito netting, and by drug therapy to kill

the parasites in the human host.

Discoveries of the causes of epidemics and transmissi-

ble diseases led to the expansion of the fields of sanitation

and public health. Draining of marshes, control of the water

supply, widespread vaccinations, and quarantine measures

improved human health. But, despite the development of

advanced detection techniques and control measures to fight

pathogens and their spread, communicable diseases still take

their toll on human populations. For example, until the

1980s tuberculosis had been declining in the United States

due in large part to the availability of effective antibiotic

therapy. However, since 1985, the number of tuberculosis

cases has risen steadily due to such factors as the emergence

of drug-resistant strains of the tubercle bacillus, the increas-

ing incidence of HIV infection which lowers human

resis-

tance

to many diseases, poverty, and immigration.

Epidemiologists track communicable diseases

throughout the world, and their work has helped to eradicate

smallpox, one of the world’s most deadly communicable

diseases. A successful global vaccination campaign wiped

out smallpox in the 1980s, and today, the

virus

exists only

in tightly-controlled laboratories in Moscow and in Atlanta

at the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

. Scien-

tists are currently debating whether to destroy the viruses

or preserve them for study.

Communicable diseases continue to be a major public

health problem in developing countries. In the small West

African nation of Guinea-Bissau, a cholera epidemic hit in

1990. Epidemiologists traced its outbreak to contaminated

shellfish and managed to control the epidemic, but not before

it claimed hundreds of lives in that country. Some victims

had eaten the contaminated shellfish, others were infected

by washing the bodies of cholera victims and then preparing

funeral feasts without properly washing their hands. Proper

disposal of victims’ bodies, coupled with a campaign to en-

courage proper hygiene, helped stop the epidemic from

spreading.

Communicable diseases can be prevented either by

eliminating the pathogenic organism from the

environment

(as by killing pathogens or parasites existing in a water

supply) or by placing a barrier in the path of its transmission

from one organism to another (as by vaccination or by isolat-

ing individuals already infected). But identifying and isolat-

ing the causal agent and developing weapons to fight it is

time consuming, and, as with the

AIDS

virus, thousands of

people continue to become infected and many die because

educational warnings about ways to avoid infection fre-

quently go unheeded.

AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV). Spread by contact with bodily fluids of an HIV-

291

infected person, the virus weakens and eventually destroys

the body’s immune system. Researchers think the virus origi-

nated in monkeys and was first transmitted to humans about

40 years ago. African

chimpanzees

can be infected with

HIV, but don’t develop AIDS. This suggests questions that

are so far unanswered: Was there a genetic change in the

virus, or was there simply more contact between monkeys

and people as human populations encroached on their

habitat

?

Some scientists think the AIDS pandemic is just the

tip of the iceberg. They worry that new diseases, deadlier

than AIDS, will emerge. Virologists point out that viruses,

like human populations, constantly change. Rapidly increas-

ing human populations provide fertile breeding grounds for

microbes

, including viruses and bacteria. Pathogens can

literally travel the globe in a matter of hours.

For example, the completion in 1990 of a major road

through the Amazon

rain forest

in Brazil led to outbreaks

of malaria in the region. In 1985, used tires imported to

Texas from eastern Asia transported larvae of the Asian tiger

mosquito, a dangerous carrier of serious tropical communica-

ble diseases.

Deforestation

and agricultural changes can

unleash epidemics of communicable diseases. Outbreaks of

Rift Valley fever followed the construction of the

Aswan

High Dam

, most likely because breeding grounds were cre-

ated for mosquitoes which spread the disease. In Brazil, the

introduction of cacao farming coincided with epidemics of

Oropouche fever, a disease linked to a biting insect that

thrives on discarded cacao hulls.

Continued rapid

transportation

of humans around

the world is likely to accelerate the movement of communica-

ble diseases. Poverty, lack of adequate sanitation and nutri-

tion, and the crowding of people into megacities in the

developing countries of the world only exacerbate the situa-

tion. The need for study and control of these disease is likely

to grow in the future.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Jaret, P. “The Disease Detectives.” National Geographic 179 (January 1991):

114-40.

Levine, D. “A Killer Returns.” American Health (April 1992): 9.

Roberts, L. “Disease and Death in the New World.” Science 246 (8 Decem-

ber 1989): 1245.

Community ecology

In biological

ecology

, the concept of community has been

defined in various ways, each definition offering particular

advantages and creating its own set of problems. As the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Community ecology

authors of one article in a 1987 British Ecological Society

symposium on community ecology noted, “Community

ecology may be unique amongst the branches of science in

lacking a consensus definition of the entity with which it is

principally concerned.” Daniel Botkin provides a summary

of the major alternatives: an ecological community is “either

(1) a set of interacting populations of different

species

found

in an area, meaning that the community is the living part

of an

ecosystem

; or (2) all of the species found in a local

area, whether or not they actually interact; or (3) all of the

species of the same kind found in a local area, as in a ’plant

community’ or ’animal community’.” Peter Taylor describes

an ecological community as consisting “of the populations

of different species co-inhabiting a site—a lake, the leaf litter

layer in a forest, a dung pat, and so on.”

A definition of community is significant because so

many different parts of the

environment

are investigated

under that rubric in ecology: animal, plant, insect, primate,

forest, even herbaceous plant communities. Often what is

described is a component of a community rather than a

whole community made up of many different species of plants

and animals. Such a whole assemblage in community ecology

has no scale, but it does denote a certain level of organization

and is different from components of a community, guilds,

or taxons.

Community ecology thus focuses on the living part of

ecosystems, mostly on communities of interacting popula-

tions, however circumscribed. While a community can in-

clude species thrown together by locale that do not necessar-

ily interact, community ecology generally emphasizes the

wide diversity of species interactions that exist within the

area.

Community ecologists investigate interactions under

numerous labels and categories, including on-going studies

of traditional topics such as predation,

competition

, trophic

exchanges, and others. Borrowing concepts from other disci-

plines, such as physics, ecologists are also beginning to look

closely at the linkages and assemblages that emerge from

strong versus weak interactions, or from positive compared

to negative interactions. Researchers continue to investigate

the relative importance of intra-species and inter-species

interactions in terms of their importance to community com-

position and rates of

succession

. One recent study, for

example, analyzed the importance of interspecific interac-

tions in the structuring of the geographical distribution and

abundance of a tropical stream fish community.

The importance of trophic relationships and food web

dynamics have always been recognized by ecologists, but a

recent article in the journal Ecology can still suggest that “a

step toward understanding the dynamics of communities is

to describe the pathways along which feeding interactions

occur.” Ecologists are beginning to quantify feeding interac-

292

tions, and are moving far beyond the old, linear food chain

studies to recognize the complex, multiple linkages created

by the feeding relationships among large assemblages of

species. Current research also recognizes the composite ef-

fects that trophic interactions have on the whole community.

One example of the significance of feeding relation-

ships is the continuing role of predation in community ecol-

ogy. A study might conclude that “Alaskan kelp forests are

broadly dependent on

sea otter

predation for protection

against destructive grazing.” Another might look at the tim-

ing of predation, and conclude that “temporal variability in

predation by whelks can have distinctive effects on prey,

create distinctive community compositions, and affect suc-

cessional paths in [an] intertidal community.”

Community ecologists still emphasize species interac-

tions that have been prominent through all the decades

of field research. Ecologists still claim, for example, that

“assumptions about competition lie at the heart of several

models of plant community organization.” Other articles in

the same journal Ecology reinforce this emphasis, stating e.g.,

“that competition is pervasive in the [Chihuahuan

desert

rodent] community.” Another example, in the Journal of

Ecology indicates that “interspecific competition may limit

the growth, branching, survival and berry production by

Vaccinium dwarf shrubs in a subarctic plant community.”

The degree of pattern or randomness of community

structure has long been an issue in community ecology.

Natural communities are immensely complex and it is diffi-

cult to simplify this complexity down to useable, predictive

models. Researchers continue to investigate the extent to

which species’ interactions can result in a unit organized

enough to be considered a coherent community. The me-

chanics of community assembly depend heavily on invasions,

rates of succession, and on changes in the physical environ-

ment, as well as a diversity of co-evolutionary patterns.

A debate still continues among community ecologists

about the importance of complexity, the role of species diver-

sity and richness in the maintenance of a community. Com-

munity structure patterns might be dependent, in part, on

factors as seemingly trivial as seed weight.

Accuracy

in

estimations of the number of species in a given community

is difficult, including the large number of

microorganisms

as yet unidentified and unnamed. Statistical inference can

help to dilute this issue somewhat.

Disturbances and perturbations are important factors

in the composition and character of communities. One study

may focus on the role of fire in tall tussock

grasslands

.

Another recent study of old-growth forests in British Co-

lumbia concluded that “small-scale natural disturbances in-

volving the death of one to a few trees and creating gaps in the

forest canopy are key processes in the...community ecology of

many forests.” In the recent “landscape view” emerging in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Compaction

ecology, some research indicates that natural communities

may persist in patches, as long as they remain interconnected.

This underlines again the importance of context in any at-

tempt to understand community ecology.

The most significant source of disturbance and change

in natural communities is human activity. Recent studies in

community ecology have documented the impact of human

removal and then reintroduction of a

keystone species

such

as largemouth bass into a lake; have questioned the impact

of “importing” an alien seaweed from Japan to expand Brit-

tan’s kelp farms; and have indicated that “human fishing

pressure has influenced Caribbean

coral reef

community

structure by affecting predator-herbivore relationships.” Hu-

mans can also have positive effects through deliberate at-

tempts to offset destructive impacts. A recent study pub-

lished in the journal Nature described the deliberate

modification of

pH

levels in lakes by adding phosphate

fertil-

izer

, which reversed

acidification

without “drastically alter-

ing the community structure.” Such manipulations, modifi-

cations, alterations, and disruptions by humans could

obviously be expanded into a very long list, but the idea

should be clear.

One other type of human impact, however, is receiving

a lot of attention: evidence is mounting that

climate

change

is increasingly impacting natural communities. For example,

one recent study suggested that “increased warming could

change the dominant vegetation of a widespread meadow

habitat

, changing the competitive relationships between

sagebrush and cinquefoil.” Another indicated that “regional

climatic warming may be altering the species composition of

Alaskan arctic tundra” through changes in light, temperature

and nutrients that affect community and ecosystem pro-

cesses.

The information gained in community ecology studies

is becoming increasingly important to achieving

conserva-

tion

objectives and establishing guidelines to management

of the natural systems on which all humans depend. For

example, clearer understanding of linkages established in

communities through trophic exchanges can help predict the

impacts of concentrations of

toxins

and pollutants. Better

understanding of organismic interactions in a community

context can help in comprehending the processes that lead

to

extinction

of species, information critical to attempts to

slow the loss of biological diversity. Research into commu-

nity dynamics can result in better decisions about establishing

preserves and refuges, and can create sustainable harvesting

strategies.

The professional ecology journals do not publish re-

search on the importance of community for the human spe-

cies. Yet, few concepts are more significant in human affairs

than the role of different kinds of community in establishing

ties and linkages among human individuals and between

293

humans and the locales in which they live. Equally important

is the lack of community, the looseness of ties and the

alienation from locale and from others that stem from failures

to establish a sense of community. As in natural communi-

ties, interactions among human individuals create commu-

nity and are in turn shaped by community.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Diamond, J., and T. Case, eds. Community Ecology. New York: Harper &

Row, 1986.

Putman, R. J. Community Ecology. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1994.

Taylor, P. “Community,” Keywords in Evolutionary Biology, ed. by E.F.

Keller and E.A. Lloyd. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Community right-to-know

see

Emergency Planning and Community

Right-to-Know Act (1986)

Compaction

Compaction is the mechanical pounding of

soil

and weath-

ered rock into a dense mass with sufficient bearing strength

or impermeability to withstand a load. It is primarily used

in construction to provide ground suitable for bearing the

weight of any given structure. With the advent of huge

earth-moving equipment we are now able to literally move

mountains. However, such disturbances loosen and expand

the soil. Thus soil must be compacted to provide an adequate

breathing surface after it has been disturbed. Inadequate

compaction during construction results in design failure or

reduced service life of a structure. Compaction, however, is

detrimental to crop production because it makes root growth

and movement difficult, and deprives the soil of access to

life-sustaining oxygen.

With proper compaction we can build enduring road-

ways, airports,

dams

, building foundation pads, or clay liners

for secure landfills. Because enormous volumes of ground

material are involved, it is far less expensive to use on-site

or nearby resources wherever feasible. Proper engineering

can overcome material deficiencies in most cases, if rigid

quality control is maintained.

Successful compaction requires a combination of

proper moisture conditioning, the right placement of mate-

rial, and sufficient pounding with proper equipment. Mois-

ture is important because dry materials seem very hard, but

they may settle or become

permeable

when wet. Because

of all the variables involved in the compaction process, stan-

dardized laboratory and field testing is essential.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Comparative risk

The American Society of State Highway

Transporta-

tion

Officials (ASHTO) and the American Society of Test-

ing Materials (ASTM) have developed specific test stan-

dards. The laboratory test involves pounding a representative

sample with a drop-hammer in a cylindrical mold. Four

uniform samples are tested, varying only in moisture content.

The sample is trimmed and weighed, and portions oven-

dried to determine moisture content.

The results are then graphed. The resultant curve nor-

mally has the shape of an open hairpin, with the high point

representing the maximum density at the optimum moisture

content for the compactive effort used. This curve reflects

the fact that dry soils resist compaction, and overly-moist-

ened soils allow the mechanical energy to dissipate. Field

densities must normally meet 95% or higher of this lab result.

Because soils are notoriously diverse, several different

“curves” may be needed; varied materials require the field

engineer to exercise considerable judgment to determine the

proper standard. Thus the field engineer and the earth-

moving crew must work closely together to establish the

procedures for obtaining the required densities.

In the past, density testing has required laboriously

digging a hole, and comparing the volume with the weight

of the material removed. Nuclear density gages have greatly

accelerated this process and allow much more frequent test-

ing if needed or desired. To take a reading, a stake is driven

into the ground to form a hole into which a sealed nuclear

probe can be lowered.

It is much easier to properly compact materials during

construction than to try to make corrections later. A well-

compacted, properly tested structure is an investment in the

future, well worth the time and effort expended.

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

American Society for Testing & Materials. Compaction of Soils. ASTM

Special Technical Publication, No. 377. Philadelphia: ASTM, 1965.

Daniel, D. P. “Summary Review of Construction Quality Control for

Compacted Soil Liners.” In Waste Containment Systems: Construction, Regu-

lation, and Performance, edited by R. Bonaparte. New York: American

Society of Civil Engineers, 1990.

Comparative risk

Initiated by the United States Environmental Protection

Agency’s (EPA) federal Comparative Risk Project in 1986,

comparative risk projects by the end of the twentieth century,

there were 46 projects underway. Furthermore, today the

priority setting method had gained national attention as

many members of Congress, federal professionals, and policy

294

experts agree that environmental protection and public

health agencies should, when setting priorities, consider the

relative degree of risk their actions will reduce. However,

while proponents tout comparative risk as a rational approach

to making decisions about priorities, critics among national

and grassroots environmental organizations believe that

comparative risk ranking can be a “hard” technocratic ap-

proach that ignores non-risk factors in decision making, is

“undemocratic,” and is contrary to

pollution

prevention or

the will of the people.

In the past, risk has not been factored into environ-

mental priority setting and, as remarked by William Ruckels-

haus, who twice served as EPA administrator, it “was hardly

mentioned in the early years of EPA, and it does not have

an important place in the Clean Air or Clean Water Acts

passed in that period.” But, building on Ruckelshaus’s

groundwork in comparative risk, EPA Administrator Lee

Thomas helped thrust the concept onto the national agenda

in 1986 when he asked 75 agency professionals to examine

31 environmental problems in the areas of

cancer

, non-

cancer, and ecological risks as well as welfare effects (

visibil-

ity

impairment, damage to statuary from

acid rain

, etc.).

In their 1987 report to Thomas, Unfinished Business: A Com-

parative Assessment of Environmental Problems, the profes-

sionals reported that, “Overall, EPA’s priorities appear more

closely aligned with public opinion than with our estimated

risks.” For instance, the EPA professionals regarded indoor

air pollution

and global warming as relatively high risks

and contaminated

hazardous waste

sites as relatively low

risk problems, while opinion polls showed that the public

had an opposite ranking. In releasing the report, Thomas

noted that EPA has finite resources and therefore must

choose its priorities carefully “so that we apply those re-

sources as effectively as possible” in reducing risks. The

EPA report became the first significant study suggesting

that national environmental priorities were inconsistent with

the experts’ sense of the most serious environmental prob-

lems, and instead the nation’s priorities were guided by public

perceptions of risk.

Concerns about the growing number of environmental

regulations and problems demanding attention, coupled with

the decline in resources to spend on these problems, kept

up the pressure for EPA, states, and local governments to

find a rational approach for deciding where to target finite

resources. The publication of a report in 1991, Environmen-

tal Investments: The Cost of a Clean Environment, reinforced

these concerns. That report was a first estimation of the

costs that industries and municipalities must incur through

compliance with federal

pollution control

programs. In

1991, costs were $115 billion a year—2.1% of the Gross

National Product (GNP)—but were projected to rise to $185

billion or 2.8% of the GNP by the year 2000.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Comparative risk

In late 1991, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-

N.Y.) introduced a bill (S.2132) that would have required

EPA to seek the advice of experts in ranking relative risks and

to use that information in managing its available resources to

protect society from the greatest risks. Moynihan’s bill, and

its successor in the 103rd Congress, became important ele-

ments of the debate over whether risk-based “rational” prior-

ity setting should be required to ensure more efficient risk

reduction.

Even before the 1991 EPA report on the rising costs

of environmental protection, EPA Administrator William

K. Reilly had taken up comparative risk as a central theme

of his administration and had asked the agency’s Science

Advisory Board to review the report issued by the 75 agency

professionals. The board’s response, a 1990 report called

Reducing Risk: Setting Priorities And Strategies For Environ-

mental Protection, also recommended that EPA and other

government agencies “assess the range of environmental

problems of concern and then target protective efforts at

problems that seem to be the most serious.” Far and away

the greatest expenditures of EPA resources were directed at

the agency’s construction grants program for publicly owned

wastewater

treatment plants and the cleanup of abandoned

Superfund sites—for instance, a full 70% of the agency’s

fiscal year 1990 budget of $6 billion went to these pro-

grams—even though other problems were deemed more

serious from a scientific perspective. The science advisors

also suggested that EPA should give more attention to the

relatively neglected job of protecting ecosystems, which faced

high risks from

habitat

alteration, loss of

biodiversity

,

global

climate

change, and

ozone layer depletion

.

Reducing Risk, and the general topic of whether “Worst

Things First” should be the touchstone of environmental

priority setting, was debated at a November 1992 meeting in

Annapolis, Maryland, at which critics challenged its “quasi-

scientific” claims and offered competing priority setting ap-

proaches, including a strategy that would make preventing

pollution the fundamental criterion for

environmental pol-

icy

decisions founded on the public’s decision that pollution

is undesirable. In the critics’ view, comparative

risk analysis

presumes that some pollution and its risk is acceptable.

Skepticism notwithstanding, EPA chose to foster de-

velopment of the method. As part of its endorsement of

comparative

risk assessment

as an important priority set-

ting tool, EPA promoted a series of comparative risk projects

in several of its regions—Region 1, New England; Region

3, the Mid-Atlantic states; and Region 10, the Pacific North-

west—and in three pilot states: Washington, Colorado, and

Pennsylvania. Later, Vermont, California, Utah, Michigan,

and other states joined in. Sub-state entities also developed

projects, including Columbus, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; Eliz-

abeth River, Virginia; Houston, Texas; and Wisconsin tribes.

295

Typically, comparative risk projects follow six basic

steps. First, they define and analyze the risks posed by envi-

ronmental problems facing the jurisdiction, usually working

from a list of problems. Second, they rank the problems

according to the relative severity of each, using technical

information and criteria to grade the negative impacts of

individual problems on health, ecosystems, or quality of life.

Third, they select priorities for special attention and set

goals for reducing risks posed by the problem. Fourth, they

propose, analyze, and compare strategies for achieving the

goals set in step three. Fifth, they implement strategies hav-

ing the greatest risk-reduction promise. And, sixth, they

monitor results produced by the strategies and adjust juris-

dictional policies or budgets based on those results. These

steps are carried out through committees composed of state

or local officials, industry representatives, environmentalists,

and citizens. The projects all seek to broadly incorporate

public values—not merely technical scientific information—

in assessing and ranking risks.

Among the more widely cited state comparative risk

projects is Washington Environment 2010, which, more

than any other state project, influenced legislation and state

policy. It was initiated in 1988 by Washington’s Department

of Ecology Director Christine Gregoire and included techni-

cal committees with members from 19 state agencies and a

steering committee composed of senior managers or heads

of those agencies. In addition, it had a public advisory com-

mittee composed of 34 prominent legislators, representa-

tives, and important interest groups. Resulting from this

project was a ranking of 23 threats to the environment within

five priority levels.

Ambient air

pollution, point-source dis-

charges of pollution to water, and polluted

runoff

ranked

as the top priorities, and non-ionizing radiation, materials

storage in tanks, and litter ranked as the lowest priorities.

Based on the project, and a statewide effort to solicit public

responses that produced some 300 risk-reduction options,

Washington’s legislature in 1991 adopted several new envi-

ronmental laws dealing with clean air,

transportation

de-

mand,

water conservation

,

recycling

, growth manage-

ment, and the state’s

energy policy

. The Department of

Ecology redirected $6.8 million of its budget from lower to

higher risk priorities. However, in 1993 Gregoire’s successor

reorganized the department, dismantling an Environment

2010 planning staff that had been established and, with

it, the state’s institutional memory of the comparative risk

project. Washington’s experience in this regard, and similar

experiences in other states, have made some proponents

of comparative risk assessment question how deeply and

lastingly its effects will be felt in environmental programs.

Despite such setbacks, the comparative risk concept

has continued to find a significant place in governmental

discussions of environmental policy. In 1993, the White

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Competition

House of Science and Technology Policy and the

Office of

Management and Budget

invited comparative risk analysis

experts to meet with federal government officials to explore

how the approach could be used by federal agencies to estab-

lish broad priorities more systematically. That effort resulted

in a 1996 report, Comparing Environmental Risks: Tools for

Setting Government Priorities, that proposed a basic frame-

work for using the method in federal agencies. Furthermore,

during the 104th Congress, comparative risk analysis was

one of numerous risk-related reforms that were included in

the Republican Contract With America and its agenda of

reducing regulatory burdens through a downsizing of gov-

ernment, the most far-reaching attempt to impose a “ratio-

nal” risk-based priority setting system on federal agencies.

While the future of comparative risk analysis as a basis

for establishing environmental priorities remains uncertain,

federal, state, and local interest remains strong. Today, most

practitioners and proponents of the approach recognize that

comparative risk alone will not suffice to establish priorities.

Public values, hard to quantify benefits, and other non-

scientific elements that must be weighed in decisions about

priorities have a clearly recognized role. That conclusion has

been reinforced in all the state and local projects. Some

recent studies suggest that the future progress of comparative

risk analysis requires more research on how to better inform

diverse parts of the affected public throughout the process

of setting environmental priorities. Even though federal leg-

islation that would mandate comparative risk analysis as a

basis for selecting priorities may never pass, the risk-based

approach enunciated in 1987 has emerged today as a central

piece of environmental policy and is explicitly discussed in

EPA’s draft Environmental Goals for America With Milestones

for 2005, the latest federal effort to clarify and organize

environmental priorities.

[David Clarke]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Davies, J. C., ed. Comparing Environmental Risks: Tools for Setting Govern-

ment Priorities. Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future, 1996.

Finkel, A. M., and D. Golding, eds. Worst Things First? The Debate over

Risk-Based National Environmental Priorities. Washington, D.C.: Resources

for the Future, 1994.

U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Science Advisory Board. Reducing

Risk: Setting Priorities and Strategies for Environmental Protection. Washing-

ton, D.C.: GOP, 1990.

U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Policy, Planning, and

Evaluation. Unfinished Business: A Comparative Assessment of Environmental

Problems. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1987.

296

Competition

Competition is the interaction between two organisms when

both are trying to gain access to the same limited resource.

When both organisms are members of the same

species

,

such interaction is said to be “intraspecific competition.”

When the organisms are from different species, the interac-

tion is “interspecific competition.”

Intraspecific competition arises because two members

of the same species have nearly identical needs for food,

water, sunlight, nesting space, and other aspects of the

envi-

ronment

. As long as these resources are available in abun-

dance, every member of the community can survive without

competition. When those resources are in limited supply,

however, competition is inevitable. For example, a single

nesting pair of bald eagles requires a minimum of 620 acres

(250 ha) that they can claim as their own territory. If two

pairs of eagles try to survive on 620 acres, competition will

develop, and the stronger or more aggressive pair will drive

out the other pair.

Intraspecific competition is also a factor in controlling

plant growth. When a mature plant drops seeds, the seed-

lings that develop are in competition with the parent plant

for water, sunlight, and other resources. When abundant

space is available and the size of the community is small, a

relatively large number of seedlings can survive and grow.

When population density increases, competition becomes

more severe and more seedlings die off.

Competition becomes an important limiting factor,

therefore, as the size of a community grows. Those individu-

als in the community that are better adapted to gain food,

water, nesting space, or some other limited resource are more

likely to survive and reproduce. Intraspecific competition is

thus an important factor in natural selection.

Interspecific competition occurs when members of two

different species compete for the same limited resource(s).

For example, two species of birds might both prefer the

same type of insect as a food source and will be forced to

compete for it if it is in limited supply.

Laboratory studies show that interspecific competition

can result in the

extinction

of the species less well adapted

for a particular resource. However, this result is seldom, if

ever, observed in

nature

, at least among animals. The reason

is that individuals can adapt to take advantage of slight

differences in resource supplies. In the Galapagos Islands,

for example, 13 similar species of finches have evolved from

a single parent species. Each species has adapted to take

advantage of some particular

niche

in the environment. As

similar as they are, the finches do not compete with each

other to any specific extent.

Interspecific competition among plants is a different

matter. Since plants are unable to move on their own, they