Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Eastern European pollution

The group carries out its work by recruiting volunteers

to serve in an environmental EarthCorps and to work with

research scientists on important environmental issues. The

volunteers, who pay from $800 to over $2,500 to join two-

or three-week expeditions to the far corners of the globe,

gain valuable experience and knowledge on situations that

affect the earth and human welfare.

By 2002, Earthwatch has sponsored over 1,180 proj-

ects in 50 countries around the world. By the end of the

year it expects to have mobilized 4,300 volunteers, ranging

in ages from 16 to 85, on 780 research teams. They will

address such topics as

tropical rain forest ecology

and

conservation

; marine studies (ocean ecology); geosciences

(climatology, geology, oceanography, glaciology, volca-

nology, paleontology); life sciences (

wildlife management

,

biology, botany, ichthyology, herpetology, mammalogy, or-

nithology, primatology, zoology); social sciences (agriculture,

economic anthropology, development studies, nutrition,

public health); and art and archaeology (architecture, archae-

oastronomy, ethnomusicology, folklore).

Since it was founded in 1971, Earthwatch has orga-

nized over 60,000 EarthCorps volunteers, who have contrib-

uted over $22 million and more than four million hours on

some 1,500 projects in 150 countries and 36 states. No

special skills are needed to be part of an expedition, and

anyone 16 years or older can apply. Scholarships for students

and teachers are also available. Earthwatch’s affiliate, The

Center for Field Research, receives several hundred grant

applications and proposals every year from scientists and

scholars who need volunteers to assist them on study expedi-

tions.

Earthwatch publishes Earthwatch magazine six times

a year, describing its research work in progress and the

findings of previous expeditions. The group has offices in

Los Angeles, Oxford, Melbourne, Moscow, and Tokyo and

is represented in all 50 American states as well as in Ger-

many, Holland, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland by volunteer

field representatives.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Earthwatch, 3 Clock Tower Place, Suite 100 Box 75, Maynard, MA USA

01754 (978) 461-0081, Fax: (978) 461-2332, Toll Free: (800) 776-0188,

Email: info@earthwatch.org, <http://www.earthwatch.org>

Eastern European pollution

Between 1987 and 1992 the disintegration of Communist

governments of Eastern Europe allowed the people and press

of countries from the Baltic to the Black Sea to begin re-

407

counting tales of life-threatening

pollution

and disastrous

environmental conditions in which they lived. Villages in

Czechoslovakia were black and barren because of

acid rain

,

smoke

, and

coal

dust from nearby factories. Drinking water

from Estonia to Bulgaria was tainted with toxic

chemicals

and untreated sewage. Polish garden vegetables were inedible

because of high

lead

and

cadmium

levels in the soil.

Chronic health problems were endemic to much of the re-

gion, and none of the region’s new governments had the

spare cash necessary to alleviate their environmental liabil-

ities.

The air,

soil

, and

water pollution

exposed by new

environmental organizations and by a newly vocal press had

its roots in Soviet-led efforts to modernize and industrialize

Eastern Europe after 1945. (Often the term “Central Eu-

rope” is used to refer to Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia,

Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria, and “Eastern Europe”

to refer to the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. For the

sake of simplicity, this essay uses the latter term for all these

states.) Following Stalinist theory that modernization meant

industry, especially heavy industries such as coal mining, steel

production, and chemical manufacturing, Eastern European

leaders invested heavily in industrial buildup. Factories were

often built in resource-poor areas, as in traditionally agricul-

tural Hungary and Romania, and they rarely had efficient

or clean technology. Production quotas generally took prece-

dence over health and environmental considerations, and

billowing smokestacks were considered symbols of national

progress. Emission controls on smokestacks and waste

efflu-

ent

pipes were, and are, rare. Soft, brown lignite coal, cheap

and locally available, was the main fuel source. Lignite con-

tains up to 5% sulfur and produces high levels of

sulfur

dioxide

,

nitrogen oxides

, particulates, and other pollutants

that contaminate air and soil in population centers, where

many factories and

power plants

were built. The region’s

water quality

also suffers, with careless disposal of toxic

industrial wastes, untreated urban waste, and

runoff

from

chemical-intensive agriculture.

By the 1980s the effects of heavy industrialization

began to show. Dependence on lignite coal led to sulfur

dioxide levels in Czechoslovakia and Poland eight times

greater than those of Western Europe. The industrial trian-

gle of Bohemia and Silesia had Europe’s highest concentra-

tions of ground-level

ozone

, which harms human health

and crops. Acid rain, a result of industrial

air pollution

,

had destroyed or damaged half of the forests in the former

East Germany and the Czech Republic. Cities were threat-

ened by outdated factory equipment and aging chemical

storage containers and pipelines, which leaked

chlorine

,

aldehydes, and other noxious gases. People in cities and

villages experienced alarming numbers of

birth defects

and

short life expectancies. Economic losses, from health care

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Eastern European pollution

expenses, lost labor, and production inefficiency further

handicapped hard-pressed Eastern European governments.

Popular protests against environmental conditions

crystallized many of the movements that overturned Eastern

and Central European governments. In Latvia, expose

´

son

petrochemical poisoning

and on environmental conse-

quences of a hydroelectric project on Daugava River sparked

the Latvian Popular Front’s successful fight for indepen-

dence. Massive campaigns against a proposed dam on the

Danube River helped ignite Hungary’s political opposition

in 1989. In the same year, Bulgaria’s Ecoglasnost group held

Sofia’s first non-government rally since 1945. The Polish

Ecological Club, the first independent environmental orga-

nization in Eastern Europe, assisted the Solidarity move-

ment in overturning the Polish government in the mid-

1980s.

Citizens of these countries rallied around environmen-

tal issues because they had first-hand experience with the

consequences of pollution. In Espenhain, of former East

Germany, 80% of children developed chronic

bronchitis

or

heart ailments before they were eight years old. Studies

showed that up to 30% of Latvian children born in 1988

may have suffered from birth defects, and both children and

adults showed unusually high rates of

cancer

,

leukemia

,

skin diseases, bronchitis, and asthma. Czech children in

industrial regions had acute

respiratory diseases

, weak-

ened immune systems, and retarded bone development, and

concentrations of lead and cadmium were found in children’s

hair. In the industrial regions of Bulgaria skin diseases were

seven times more common than in cleaner areas, and cases

of rickets and liver diseases were four times as common.

Much of the air and soil contamination that produced these

symptoms remains today and continues to generate health

problems.

Water pollution is at least as threatening as air and

soil pollution. Many cities and factories in the region have

no facilities for treating

wastewater

and sewage. Existing

treatment facilities are usually inadequate or ineffective.

Toxic waste dumps containing old and rusting barrels of

hazardous materials are often unmonitored or unidentified.

Chemical

leaching

from poorly monitored waste sites

threatens both surface water and

groundwater

, and water

clean enough to drink has become a rare commodity. In

Poland untreated sewage, mine

drainage

, and factory efflu-

ents make 95% of water unsafe for drinking. At least half

of Polish rivers are too polluted, by government assessment,

even for industrial use. According to government officials,

70% of all rivers in the industrial Czech region of Bohemia

are heavily polluted, 40% of wastewater goes untreated, and

nearly a third of the rivers have no fish. In Latvia’s port

town of Ventspils, heavy oil lies up to 3 ft (1 m) thick on

408

the river bottom. Phenol levels in the nearby Venta River

exceed official limits by 800%.

Few pollution problems are geographically restricted

to the country in which they were generated. Shared rivers

and aquifers and regional weather patterns carry both air-

borne and water-borne pollutants from one country to an-

other. The Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster, which spread

radioactive gases and particulates from Belarus across north-

ern Europe and the Baltic Sea to northern Norway and

Sweden is one infamous example of trans-border pollution,

but other examples are common. The town of Ruse, Bulgaria

has long been contaminated by chlorine gas emissions from

a Romanian plant just across the Danube. Protests against

this poisoning have unsettled Bulgarian and Romanian rela-

tions since 1987. Toxic wastes flowing into the Baltic Sea

from Poland’s Vistula River continue to endanger fisheries

and shoreline habitats in Sweden, Germany, and Finland.

The Danube River is a particularly critical case. Accu-

mulating and concentrating urban and industrial waste from

Vienna to the Black Sea, this river supports industrial com-

plexes of Austria, Czechia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bul-

garia, and Romania. Before the Danube leaves Budapest, it

is considered unsafe for swimming. Like other rivers, the

Danube flows through a series of industrial cities and mining

regions, each river uniting the pollution problems of several

countries. Each city and farm along the way uses the contam-

inated water and contributes some pollutants of its own.

Also like other rivers, the Danube carries its toxic load into

the sea, endangering the marine environment.

Western countries from Sweden to the United States

have their share of pollution and environmental disasters.

The Rhine and the Elbe have disastrous

chemical spills

like

those on the Danube and the Vistula. Like recent communist

regimes, most western business leaders would prefer to disre-

gard environmental and human health considerations in their

pursuit of production quotas. Yet several factors set apart

environmental conditions in Eastern Europe. Aside from its

aged and outdated equipment and infrastructure, Eastern

Europe is handicapped by its compressed geography, intense

urbanization near factories, a long-standing lack of informa-

tion and accurate records on environmental and health con-

ditions, and severe shortages of clean-up funds, especially

hard currency.

Eastern Europe’s dense settlement crowds all the in-

dustrial regions of the Baltic states, Poland, the Czech and

Slovak republics, and Hungary into an area considerably

smaller than Texas but with a much higher population.

This industrial zone lies adjacent to crowded manufacturing

regions of Western Europe. In this compact region, people

farm the same fields and live on the same mountains that

are stripped for mineral extraction. Cities and farms rely on

aquifers and rivers that receive factory effluent and

pesticide

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ebola

runoff immediately upstream. Furthermore, post-1945 in-

dustrialization gathered large labor forces into factory towns

more quickly than adequate infrastructure could be built.

Expanding urban populations had little protection from the

unfiltered pollutants of nearby furnaces. At the same time

that many Eastern Europeans were eye witnesses to environ-

mental transgressions, little public discussion about the prob-

lem was possible. Official media disliked publicizing health

risks or the destruction of forests, rivers, and lakes. Those

statistics

that existed were often unreliable. Air and water

quality data were collected and reported by industrial and

government officials, who could not afford bad test results.

Now that environmental conditions are being exposed,

cleanup efforts remain hampered by a shortage of funding.

Poland’s long-term environmental restoration may cost $260

billion, or nearly eight times the country’s annual GNP in

the mid-1980s. Efforts to cut just sulfur dioxide emissions

to Western standards would cost Poland about $2.4 billion

a year. Hungary, with a mid-1980s GNP of $25 billion,

could begin collecting and treating its sewage for about $5

billion. Cleanup in the port of Ventspils, Latvia, is expected

to cost 3.6 billion rubles and $1.5 billion in hard currency.

East German air, soil, and water

remediation

get a boost

from their western neighbors, but the bill is expected to run

between $40 and $150 billion.

Ironically, East European leaders see little choice for

raising this money aside from expanded industrial produc-

tion.Meanwhile, business leaders urge production expansion

for other capital needs. Some Western investment in cleanup

work has begun, especially on the part of such countries as

Sweden and Germany, which share rivers and seas with

polluting neighbors. Already in 1989 Sweden had begun

work on water quality monitoring stations along Poland’s

Vistula River, which carries pollutants into the Baltic Sea.

Capital necessary to purchase mitigation equipment, im-

prove factory conditions, rebuild rusty infrastructure, and

train environmental experts will probably be severely limited

for decades to come, however.

Meanwhile, western investors are flocking to Eastern

and Central Europe in hopes to build or rebuild business

ventures for their own gain. The region is seen as one of

quick growth and great potential. Manufacturers in heavy

and light industries, automobiles, power plants, and home

appliances are coming from Western Europe, North

America, and Asia. From textile manufacturing to agribusi-

ness, outside investors hope to reshape Eastern economies.

Many Western companies are improving and updating

equipment and adding

pollution control

devices. In a

cli-

mate

of uncertain regulation and rushed economic growth,

however, no one knows if the region’s new governments will

be able or willing to enforce environmental safeguards or if

409

the new investors will take advantage of weak regulations

and poor enforcement as did their predecessors.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

French, H. F. “Restoring the Eastern European and Soviet Environments.”

In State of the World 1991. New York: Norton, 1991.

Feshbach, M., and A. Friendly, Jr. Ecocide in the USSR. New York: Basic

Books, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Hartsock, J. “Latvia’s Toxic Legacy.” Audubon 94 (1992): 27-8.

Wallich, P. “Dark Days: Eastern Europe Brings to Mind the West’s Pol-

luted History.” Scientific American 263 (1990): 16, 20.

Ebola

Ebola is a highly deadly viral hemorrhagic disease. As the

disease progresses, the walls of blood vessels break down

and blood gushes from every tissue and organ. The disease

is caused by the Ebola

virus

, named after the river in Zaire

(now the Democratic Republic of Congo) where the first

known outbreak occurred. The disease is extremely conta-

gious and exceptionally lethal. Where a 10%

mortality

rate

is considered high for most infectious diseases, Ebola can

kill up to 90% of its victims, usually within only a few

days after exposure. It seems to take direct contact with

contaminated blood or bodily fluids to catch the disease.

Health personnel and caregivers are often the most likely to

be infected. Even after a patient has died, preparing the

body for a funeral can be deadly for families members.

The Ebola virus is one of two members of a family of

RNA viruses called the Filoviridae. The other filovirus causes

Marburg fever, an equally contagious and lethal hemorrhagic

disease, named after a German town where it was first con-

tracted by laboratory workers who handled imported mon-

keys infected with the virus. Together with members of three

other families (arenaviruses, bunyanviruses, and flaviviruses),

these viruses cause a group of deadly, episodic diseases in-

cluding Lassa fever, Rift Valley fever, Bolivian fever, and

Hanta or Four-Corners fever (named after the region of the

southwestern United States where it was first reported).

The viruses associated with most of these emergent,

hemorrhagic fevers are zoonotic. That means a

reservoir

of pathogens naturally resides in an animal host or arthropod

vector. We don’t know the specific host or vector for Ebola,

but monkeys and other primates can contract related dis-

eases. People who initially become infected with Ebola often

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ebola

have been involved in killing, butchering, and eating gorillas,

chimps, or other primates. Why the viruses remain peacefully

in their hosts for many years without causing much more

trouble than a common cold, but then erupt sporadically

and unpredictably into terrible human epidemics, is a new

and growing question in

environmental health

.

The geographical origin for Ebola is unknown, but all

recorded outbreaks have occurred in or around Central Af-

rica, or in animals or people from this area. Ebola appears

every few years in Africa. Confirmed cases have occurred in

the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Sudan,

Uganda, and the Ivory Coast. No case of the disease in

humans has ever been reported in the United States, but a

variant called Ebola-Reston virus killed a number of mon-

keys in a research facility in Reston, Virginia. A fictionalized

account of this outbreak was made into a movie called “Hot

Zone.” There probably are isolated cases in remote areas that

go unnoticed. In fact, the disease may have been occurring in

secluded villages deep in the jungle for a long time without

outside attention. The most recent Ebola outbreak was in

2002 when about 100 people died in a remote part of Gabon

and an adjacent area in Congo.

The worst epidemic of Ebola in humans occurred in

1995, in Kikwit, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of

Congo). Although many more people died in Kikwit that

in any other outbreak, in many ways, the medical and social

effects of the epidemic there was typical of what happens

elsewhere. The first Kikwit victim was a 36-year-old labora-

tory technician named Kimfumu, who checked into a medi-

cal clinic complaining of a severe headache, stomach pains,

fever, dizziness, weakness, and exhaustion. Surgeons did an

exploratory operation to try to find the cause of his illness.

To their horror, they found his entire gastrointestinal tract

was necrotic and putrefying. He bled uncontrollably, and

within hours was dead. By the next day, the five medical

workers who had cared for Kimfumu, including an Italian

nun who assisted in the operation, began to show similar

symptoms, including high fevers, fatigue, bloody diarrhea,

rashes, red and itchy eyes, vomiting, and bleeding from every

body orifice. Less than 48 hours later, they, too, were dead,

and the disease was spread throughout the city of 600,000.

As panicked residents fled into the bush, government

officials responded to calls for help by closing off all travel—

including humanitarian aid—into or out of Kikwit, about

250 mi (400 km) from Kinshasa, the national capitol. Fearful

neighboring villages felled trees across the roads to seal off

the pestilent city. No one dared enter houses where dead

corpses rotted in the intense tropical heat. Boats plying the

adjacent Kwilu River refused to stop to take on or

discharge

passengers or cargo. Food and clean water became scarce.

Hospitals could hardly function as medicines and medical

personal became scarce. Within a few weeks, about 400

410

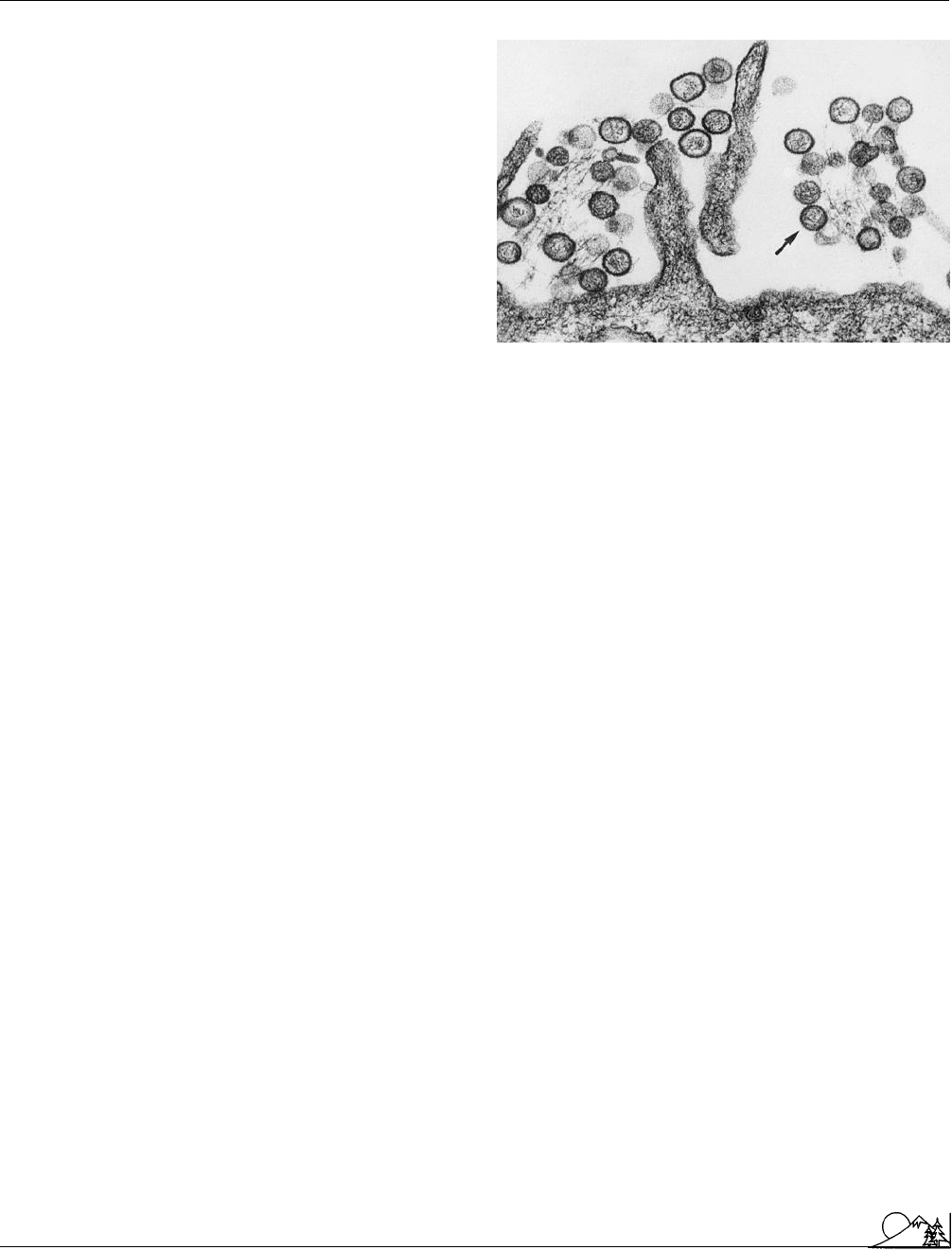

An electron micrograph of the ebola virus and

the hanta virus. (Delmar Publishers Inc. Reproduced

by permission.)

people in Kikwit had contracted the disease and at least 350

were dead. Eventually, the epidemic dissipated and disap-

peared. It isn’t known why the infection rate dropped or

what residents might do to prevent a further reappearance

of the terrible disease.

Because health professionals are among the most likely

to be exposed to Ebola when an outbreak occurs, it is impor-

tant for them to have access to rapid antigen or antibody

assays and isolation facilities to prevent further spread of

the virus. Unfortunately, these advanced medical procedures

generally are lacking in the African hospitals where the

disease is most likely to occur. There is no standard treatment

for Ebola other than supportive therapy. Patients are given

replacement fluids and electrolytes, and oxygen levels and

blood pressure are stabilized as much as possible. During

the Kikwit outbreak, eight patients were given blood of

individuals who had been infected with the virus but who

had recovered. It was hoped that their blood might have

antibodies to fight the infection. Seven of the eight transfu-

sion patients survived, but the number tested is too small

to be sure this was statistically significant. There is no vaccine

or other antiviral drug available to prevent or halt an in-

fection.

Several factors seem to be contributing to the appear-

ance and spread of highly contagious diseases such as Ebola

and Marburg fevers. With 6 billion people now inhabiting

the planet, human densities are much higher enabling germs

to spread further and faster than ever before. Expanding

populations push people into remote areas where they en-

counter new pathogens and

parasites

. Environmental

change is occurring on a larger scale: cutting forests, creating

unhealthy urban surroundings, and causing global-climate

change, among other things. Elimination of predators and

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Eco Mark

habitat

changes favor disease-carrying organisms such as

mice, rats, cockroaches, and mosquitoes.

Another important factor in the spread of many dis-

eases is the speed and frequency of modern travel. Millions

of people go every day from one place to another by airplane,

boat, train, or

automobile

. Very few places on earth are

more than 24 hours by jet plane from any other place. In

2001, a woman flying from the Congo arrived in Canada

delirious with a high fever. She didn’t, in fact, have Ebola,

but Canadian officials were concerned about the potential

spread of the disease. Finding ways to cure Ebola and prevent

its spread may be more than simply a humanitarian concern

for its victims in Central Africa. It might be very much in

our own self-interest to make sure that this terrible disease

doesn’t cross our borders either accidentally or intentionally

through actions of a terrorist organization.

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Close, William T. Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People. London: Meadow-

lark Springs Productions, 2001.

Drexler, Madeline. Secret Agents: the Menace of Emerging Infections. Joseph

Henry Press, 2002.

Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. Anchor Books, 1995.

O

THER

Disease Information Fact Sheets: Ebola hemorrhagic fever. 2002. Center for

Disease Control and Prevention. [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.cdc.gov/

ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/dispages/ebola.html>.

P

ERIODICALS

Daszak, P. et al. 2000."Emerging Infectious Diseases of Wildlife-Threats

to Biodiversity and Human Health.” Science(US) 287: 443-449.

Hughes, J.M. “Emerging infectious diseases: a CDC perspective.” Emerging

Infectious Diseases. 7(2001):494-6.

Osterholm, M. T. “Emerging Infections—Another Warning.” The New

England Journal of Medicine 342(17): 4-5.

Eco Mark

The Japanese environmental label known as “Eco Mark” is

a relatively new addition to a worldwide effort to designate

products that are environmentally friendly. The Eco Mark

program was launched in February 1989. The symbol is two

arms embracing the world, symbolizing the protection of

the earth. The arms create the letter “e” with the earth in

the center. Indicating English as the international language,

the Japanese use “e” to stand for

environment

, earth, and

ecology

.

The Japanese program is entirely government funded,

although a small fee is charged to applicant industries. The

annual fee is based on the retail price of a product, not

411

annual product sales as is the case for other national green

labeling programs. Products ranging in price from $0–7 are

charged an annual fee of $278.00; from $7–70 are charged

an annual fee of $417; from $70–700 are charged an annual

fee of $556; and products priced over $700 are charged an

annual fee of $700. Obviously, those products that are low

in price and high in volume sold are most likely to apply

for the Eco Mark label.

The Eco Mark program seeks to sanction products

with the following four qualities: 1) minimal environmental

impact from use; 2) significant potential for improvement

of the environment by using the product; 3) minimal envi-

ronmental impact from disposal after use; and 4) other signif-

icant contributions to improve the environment.

In addition, labeled products must comply with the

following guidelines: 1) appropriate environmental

pollu-

tion control

measures are provided at the stage of produc-

tion; 2) ease of treatment for disposal of product; 3) energy

or resources are conserved with use of product; 4) compliance

with laws, standards, and regulations pertaining to quality

and safety; 5) price is not extraordinarily higher than compa-

rable products.

The Environment Association, supervised by the Japa-

nese Environment Agency, is in charge of the Eco Mark

program. All technical, research, and administrative support

is provided by the government. The labeling program is

guided by two committees.

The Eco Mark Promotion Committee acts primarily

in a supervisory capacity, approving the guidelines for the

program’s operation and advising on operations, including

evaluation of the program categories and criteria. The pro-

motion committee consists of nine members representing

industry, marketing groups, local governments, environmen-

tal agencies, and the National Institute for Environmental

Studies.

In addition to the Promotion Committee there is a

committee for approval of products. This committee consists

of five members with representation from the science com-

munity, the consumer protection community, and, as in

the Promotion Committee, a representative each from the

Environment Agency and the National Institute for Envi-

ronmental Studies. The Japanese program is completely vol-

untary for manufacturers. Once a product is approved by

the Approval Committee, a two-year renewable licensing

contract for the use of the Eco Mark is signed with the

Japan Environment Association.

The Eco Mark program is very goal-oriented and

places great emphasis on overall environmental impact. The

attention to production impacts, as well as use and disposal

impacts, makes the program unique within the family of

green labeling programs worldwide. Its primary goals are to

encourage innovation by industry and elevate the environ-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ecocide

mental awareness and consumer behavior of the Japanese

people in order to enhance environmental quality.

Japan’s Environment Agency claims that responses

from consumer and environmental organizations have been

positive, while industry has been less than enthusiastic. In

fact, the Eco Mark only covered seven products in 1989 and

now covers over 5,000. Some scientists have voiced concern

over the superficiality of the analysis procedure used to deter-

mine Eco Mark products. However, despite criticisms, the

Japanese Eco Mark program is a strong national effort to

encourage environmentally sound decisions and protect the

environment for

future generations

in that country. See also

Environmental policy; Green packaging; Green products;

Precycling; Recycling; Reuse; Waste reduction

[Cynthia Fridgen]

F

URTHER

R

EADING

Salzman, J. Environmental Labeling in OECD Countries. Paris, France:

OECD Technology and Environmental Program, 1991.

Ecoanarchism

see

Ecoterrorism

Ecocide

Any substance that enters an ecological system, spreads

throughout that system, and kills enough members of the

ecosystem

to disrupt its structure and function. For exam-

ple, on July 14, 1991, a freight train carrying the

pesticide

metam sodium fell off a bridge near Dunsmuir, California,

spilling its contents into the Sacramento River. When mixed

with water this pesticide becomes highly poisonous, and all

animal life for some distance downstream of the spill site

was killed.

Ecofeminism

Coined in 1974 by the French feminist Francoise d’Eau-

bonne, ecofeminism, or ecological feminism, is a recent

movement that asserts that the

environment

is a feminist

issue and that feminism is an environmental issue. The term

ecofeminism has come to describe two related movements

operating at somewhat different levels: (1) the grassroots,

women-initiated activism aimed at eliminating the oppres-

sion of women and

nature

; and (2) a newly emerging branch

of philosophy that takes as its subject matter the foundational

questions of meaning and justification in feminism and

envi-

ronmental ethics

. The latter, more properly termed eco-

feminist philosophy, stands in relation to the former as

412

theory stands to practice. Though closely related, there nev-

ertheless remain important methodological and conceptual

distinctions between action- and theory-oriented ecofem-

inism.

The ecofeminist movement developed from diverse

beginnings, nurtured by the ideas and writings of a number

of feminist thinkers, including Susan Griffin, Carolyn Mer-

chant, Rosemary Radford Ruether, Ynestra King, Ariel Sal-

leh, and Vandana Shiva. The many varieties of feminism

(liberal, marxist, radical, socialist, etc.) have spawned as many

varieties of ecofeminism, but they share a common ground.

As described by Karren Warren, a leading ecofeminist phi-

losopher, ecofeminists believe that there are important con-

nections—historical, experiential, symbolic, and theoreti-

cal—between the domination of women and the domination

of nature. In the broadest sense, then, ecofeminism is a

distinct social movement that blends theory and practice to

reveal and eliminate the causes of the dominations of women

and of nature.

While ecofeminism seeks to end all forms of oppres-

sion, including racism, classism, and the abuse of nature,

its focus is on gender bias, which ecofeminists claim has

dominated western culture and led to a patriarchal, masculine

value-oriented hierarchy. This framework is a socially con-

structed mindset that shapes our beliefs, attitudes, values,

and assumptions about ourselves and the natural world.

Central to this patriarchal framework is a pattern of

thinking that generates normative dualisms. These are cre-

ated when paired complementary concepts such as male/

female, mind/body, culture/nature, and reason/emotion are

seen as mutually exclusive and oppositional. As a result of

socially-entrenched gender bias, the more “masculine” mem-

ber of each dualistic pair is identified as the superior one.

Thus, a value hierarchy is constructed which ranks the mas-

culine characteristics above the feminine (e.g., culture above

nature, man above woman, reason above emotion). When

paired with what Warren calls a “logic of domination,” this

value hierarchy enables people to justify the subordination

of certain groups on the grounds that they lack the “superior”

or more “valuable” characteristics of the dominant groups.

Thus, men dominate women, humans dominate nature, and

reason is superior to emotion. Within this patriarchal con-

ceptual framework, subordination is legitimized as the neces-

sary oppression of the inferior. Until we reconceptualize

ourselves and our relation to nature in non-patriarchal ways,

ecofeminists maintain, the continued dual denigration of

women and nature is assured.

Val Plumwood, an Australian ecofeminist philoso-

pher, has traced the roots of the development of the oppres-

sion of women and the exploitation of nature to three points,

the first two points sharing historical origins, the third having

its genesis in human psychology. In the first of these histori-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ecofeminism

cal women-nature connections, dualism has identified higher

and lower “halves.” The lower halves, seen as possessing less

or no

intrinsic value

relative to their polar opposites, are

instrumentalized and subjugated to serve the needs of the

members of the “higher” groups. Thus, due to their historical

association and supposedly shared traits, women and nature

have been systematically devalued and exploited to serve the

needs of men and culture.

The second of these historical women-nature connec-

tions is said to have originated with the rise of mechanistic

science before and during the Enlightenment period. Ac-

cording to some ecofeminists, dualism was not necessarily

negative or hierarchical; however, the rise of modern science

and technology, reflecting the transition from an organic to

a mechanical view of nature, gave credence to a new logic

of domination. Rationality and scientific method became

the only socially sanctioned path to true knowledge, and

individual needs gained primacy over community. On this

fertile

soil

were sown the seeds for an ethic of exploitation.

A third representation of the connections between

women and nature has its roots in human psychology. Ac-

cording to this account, the features of masculine conscious-

ness which allow men to objectify and dominate are the

result of sexually-differentiated personality development. As

a result of women’s roles in both creating and maintaining/

nurturing life, women develop “softer” ego boundaries than

do men, and thus they generally maintain their connected-

ness to other humans and to nature, a connection which is

reaffirmed and recreated generationally. Men, on the other

hand, psychologically separate both from their human moth-

ers and from Mother Earth, a process which results in their

desire to subdue both women and nature in a quest for

individual potency and transcendence. Thus, sex differences

in the development of self/other identity in childhood are

said to account for women’s connectedness with, and men’s

alienation from, both humanity and nature.

Ecofeminism has attracted criticism on a number of

points. One is the implicit assumption in certain ecofeminist

writings that there is some connection between women and

nature that men either do not possess or cannot experience.

And, why female activities such as birth and childcare should

be construed as more “natural” than some traditional male

activities remains to be demonstrated. This assumption,

though, has left some ecofeminists open to charges of having

constructed a new value hierarchy to replace the old, rather

than having abandoned hierarchical conceptual frameworks

altogether. Hints of hierarchical thinking can be found in

such ecofeminist practices as goddess worship and in the

writings of some radical ecofeminists who advocate the aban-

donment of reason altogether in the search for an appropriate

human-nature relationship. Rather than having destroyed

gender bias, some ecofeminists are accused of merely at-

413

tempting to reverse its polarity, possibly creating new, subtle

forms of women’s oppression. Additionally, some would

argue that ecofeminism runs the risk of oversimplification

in suggesting that all struggles between dominator and op-

pressed are one and the same and thus can be won

through unity.

A lively debate is currently underway concerning the

compatibility of ecofeminism with other major theories or

schools of thought in environmental philosophy. For in-

stance, discussions of the similarities and differences between

ecofeminism and

deep ecology

occupy a large portion of

the recent theoretical literature on ecofeminism. While deep

ecologists are primarily concerned with anthropocentrism as

the primary cause of our destruction of nature, ecofeminists

point instead to androcentrism as the key problem in this

regard. Nevertheless, both groups aim for the expansion of

the concept of “self” to include the natural world, for the

establishment of a biocentric egalitarianism, and for the

creation of connection, wholeness, and empathy with nature.

Given the newness of ecofeminism as a theoretical

discipline, it is no surprise that the nature of ecofeminist

ethics is still emerging. A number of different feminist-

inspired positions are gaining prominence, including femi-

nist

animal rights

, feminist environmental ethics based on

caregiving, feminist

social ecology

, and feminist

bioregio-

nalism

. Despite the apparent lack of a unified and over-

arching environmental philosophy, all forms of ecofeminism

do share a commitment to developing ethics which do not

sanction or encourage either the domination of any group

of humans or the abuse of nature. Already, ecofeminism has

shown us that issues in environmental ethics and philosophy

cannot be meaningfully or adequately discussed apart from

considerations of social domination and control. If ecofemi-

nists are correct, then a fundamental reconstruction of the

value and structural relations of our society, as well as a

reexamination of the underlying assumptions and attitudes,

is necessary.

[Ann S. Causey]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Des Jardins, J. Environmental Ethics: An Introduction to Environmental

Philosophy. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1993.

Griffin, S. Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. New York: Harper &

Row, 1978.

P

ERIODICALS

Adams, C., and K. Warren. “Feminism and the Environment: A Selected

Bibliography.” APA Newsletter on Feminism and Philosophy (Fall 1991).

Vance, Linda. “Remapping the Terrain: Books on Ecofeminism.” Choice

30 (June 1993): 1585-93.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ecojustice

Ecojustice

The concept of ecojustice has at least two different usages

among environmentalists. The first refers to a general set of

attitudes about justice and the

environment

at the center

of which is dissatisfaction with traditional theories of justice.

With few exceptions (notably a degree of concern about

excessive cruelty to animals), anthropocentric and egocentric

Western moral and ethical systems have been unconcerned

with individual plants and animals,

species

, oceans,

wilder-

ness

areas, and other parts of the

biosphere

, except as they

may be used by humans. In general, that which is non-

human is viewed mainly as raw material for human uses,

largely or completely without moral standing.

Relying upon holistic principles of biocentrism and

deep ecology

, the “ecojustice” alternative suggests that the

value of non-human life-forms is independent of the use-

fulness of the non-human world for human purposes. Ante-

cedents of this view can be found in sources as diverse

as Eastern philosophy, Aldo Leopold’s “land ethic,” Albert

Schweitzer’s “reverence for life,” and Martin Heidegger’s

injunction to “let beings be.” The central idea of ecojustice

is that the categories of ethical and moral reflection relevant

to justice should be expanded to encompass

nature

itself and

its constituent parts, and human beings have an obligation to

take the inherent value of other living things into consider-

ation whenever these living things are affected by human

actions.

Some advocates of an ecojustice perspective base stan-

dards of just treatment on the evident capacity of many life-

forms to experience pain. Others assert the equal inherent

worth of all individual life-forms. More typically, environ-

mental ethicists assert that all life-forms have at least some

inherent worth, and thus deserve moral consideration, al-

though perhaps not the same worth. The practical goals

associated with ecojustice include the fostering of

stability

and diversity within and between self-sustaining ecosystems,

harmony and balance in nature and within competitive bio-

logical systems, and

sustainable development

.

Ecojustice can also refer simply to the linking of envi-

ronmental concerns with various social justice issues. The

advocate of ecojustice typically strives to understand how

the logic of a given economic system results in certain groups

or classes of people bearing the brunt of

environmental

degradation

. This entails, for example, concern with the

frequent location of polluting industries and

hazardous

waste

dumps near the economically disadvantaged (i.e.,

those with the least mobility and fewest resources to resist).

In much the same way, ecojustice also involves the

fostering of sustainable development in less-developed areas

of the globe, so that economic development does not mean

the export of polluting industries and other environmental

414

problems to these less-developed areas. An additional point

of concern is the allocation of costs and benefits in environ-

mental

reclamation

and preservation—for example, the

preservation of Amazonian rain forests affects the global

environment and may benefit the whole world, but the costs

of this preservation fall disproportionately upon Brazil and

the other countries of the region. An advocate of ecojustice

would be concerned that the various costs and benefits of

development be apportioned fairly. See also Biodiversity;

Ecological and environmental justice; Environmental ethics;

Environmental racism; Environmentalism; Holistic ap-

proach

[Lawrence J. Biskowski]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Miller, A. S. Gaia Connections. Savage, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1991.

Ecological consumers

Organisms that feed either directly or indirectly on produc-

ers, plants that convert

solar energy

into complex organic

molecules. Primary consumers are animals that eat plants

directly. They are also called herbivores. Secondary consum-

ers are animals that eat other animals. They are also called

carnivores. Consumers that eat both plants and animals are

omnivores.

Parasites

are a type of consumer that lives in

or on the plant or animal on which it feeds. Detrivores

(

detritus

feeders and

decomposers

) constitute a specialized

class of consumers that feed on dead plants and animals. See

also Biotic community

Ecological integrity

Ecological (or biological) integrity is a measure of how intact

or complete an

ecosystem

is. Ecological integrity is a rela-

tively new and somewhat controversial notion, however,

which means that it cannot be defined exactly. Human activi-

ties cause many changes in environmental conditions, and

these can benefit some

species

, communities, and ecological

processes, while causing damages to others at the same time.

The notion of ecological integrity is used to distinguish

between ecological responses that represent improvements,

and those that are degradations.

Challenges to ecological integrity

Ecological integrity is affected by changes in the inten-

sity of environmental stressors. Environmental stressors can

be defined as physical, chemical, and biological constraints

on the productivity of species and the processes of ecosystem

development. Many environmental stressors are associated

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ecological integrity

with the activities of humans, but some are also natural

factors. Environmental stressors can exert their influence on

a local scale, or they may be regional or even global in

their effects. Stressors represent environmental challenges

to ecological integrity.

Environmental stressors are extremely complex, but

they can be categorized in the following ways:

(1) Physical stressors are associated with brief but in-

tense exposures to kinetic energy. Because of its acute, epi-

sodic nature, this represents a type of disturbance. Examples

include volcanic eruptions, windstorms, and explosions; (2)

Wildfire

is another kind of disturbance, characterized by

the

combustion

of much of the

biomass

of an ecosystem,

and often the deaths of the dominant plants; (3)

Pollution

occurs when

chemicals

are present in concentrations high

enough to affect organisms and thereby cause ecological

changes. Toxic pollution may be caused by such gases as

sulfur dioxide

and

ozone

, metals such as

mercury

and

lead

, and pesticides. Nutrients such as phosphate and nitrate

can affect ecological processes such as productivity, resulting

in a type of pollution known as eutrophication; (4) Thermal

stress occurs when releases of heat to the

environment

cause

ecological changes, as occurs near natural hot-water vents

in the ocean, or where there are industrial discharges of

warmed water; (5) Radiation stress is associated with exces-

sive exposures to ionizing energy. This is an important stres-

sor on mountaintops because of intense exposures to

ultravi-

olet radiation

, and in places where there are uncontrolled

exposures to radioactive wastes; (6) Climatic stressors are

associated with excessive or insufficient regimes of tempera-

ture, moisture, solar radiation, and combinations of these.

Tundra

and deserts are climatically stressed ecosystems,

while tropical rain forests occur in places where the climatic

regime is relatively benign; (7) Biological stressors are associ-

ated with the complex interactions that occur among organ-

isms of the same or different species. Biological stresses

result from

competition

, herbivory, predation, parasitism,

and disease. The harvesting and management of species and

ecosystems by humans can be viewed as a type of biological

stress.

All species and ecosystems have a limited capability for

tolerating changes in the intensity of environmental stressors.

Ecologists refer to this attribute as

resistance

. When the

limits of tolerance to

environmental stress

are exceeded,

however, substantial ecological changes are caused.

Large changes in the intensity of environmental stress

result in various kinds of ecological responses. For example,

when an ecosystem is disrupted by an intense disturbance,

there will be substantial

mortality

of some species and other

damages. This is followed by recovery of the ecosystem

through the process of

succession

. In contrast, a longer-

term intensification of environmental stress, possibly caused

415

by chronic pollution or

climate

change, will result in longer

lasting ecological adjustments. Relatively vulnerable species

become reduced in abundance or are eliminated from sites

that are stressed over the longer term, and their modified

niches will be assumed by more tolerant species. Other com-

mon responses of an intensification of environmental stress

include a simplification of species richness, and decreased

rates of productivity,

decomposition

, and

nutrient

cycling.

These changes represent a longer-term change in the charac-

ter of the ecosystem.

Components of ecological integrity

Many studies have been made of the ecological

responses to both disturbance and to longer-term changes

in the intensity of environmental stressors. Such studies

have, for instance, examined the ecological effects of air

or

water pollution

, of the harvesting of species or ecosys-

tems, and the conversion of natural ecosystems into man-

aged agroecosystems. The commonly observed patterns of

change in stressed ecosystems have been used to develop

indicators of ecological integrity, which are useful in

determining whether this condition is improving or being

degraded over time. It has been suggested that greater

ecological integrity is displayed by systems that, in a

relative sense: (1) are resilient and resistant to changes in

the intensity of environmental stress. Ecological resistance

refers to the capacity of organisms, populations, or commu-

nities to tolerate increases in stress without exhibiting

significant responses. Once thresholds of tolerance are

exceeded, ecological changes occur rapidly.

Resilience

re-

fers to the ability to recover from disturbance; (2) are

biodiverse.

Biodiversity

is defined as the total richness

of biological variation, including genetic variation within

populations and species, the numbers of species in commu-

nities, and the patterns and dynamics of these over large

areas; (3) are complex in structure and function. The complex-

ity of the structural and functional attributes of ecosystems

is limited by natural environmental stresses associated with

climate,

soil

, chemistry, and other factors, and also by

stressors associated with human activities. As the overall

intensity of stress increases or decreases, structural and

functional complexity responds accordingly. Under any

particular environmental regime, older ecosystems will

generally be more complex than younger ecosystems; (4)

have large species present. The largest species in any ecosys-

tem appropriate relatively large amounts of resources,

occupy a great deal of space, and require large areas to

sustain their populations. In addition, large species tend

to be long-lived, and consequently they integrate the effects

of stressors over an extended time. As a result, ecosystems

that are affected by intense environmental stressors can

only support a few or no large species. In contrast, mature

ecosystems occurring in a relatively benign environmental

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ecological integrity

regime are dominated by large, long-lived species; (5) have

higher-order predators present. Top predators are sustained

by a broad base of

ecological productivity

, and conse-

quently they can only occur in relatively extensive and/or

productive ecosystems; (6) have controlled nutrient cycling.

Ecosystems that have recently been disturbed lose some

of their biological capability for controlling the cycling of

nutrients, and they may lose large amounts of nutrients

dissolved or suspended in stream water. Systems that are

not “leaky” of their nutrient capital are considered to have

greater ecological integrity; (7) are efficient in energy use and

transfer. Large increases in environmental stress commonly

result in community-level

respiration

exceeding productiv-

ity, resulting in a decrease in the standing crop of biomass

in the system. Ecosystems that are not losing their capital

of biomass are considered to have greater integrity than

those in which biomass is decreasing over time; (8) have

an intrinsic capability for maintaining natural ecological

values. Ecosystems that can naturally maintain their species,

communities, and other important characteristics, without

being managed by humans, have greater ecological integrity.

If, for example, a population of a

rare species

can only

be maintained by management of its

habitat

by humans,

or by a program of captive-breeding and release, then its

population, and the ecosystem of which it is a component,

are lacking in ecological integrity; (9) are components of a

“natural” community. Ecosystems that are dominated by

non-native,

introduced species

are considered to have

less ecological integrity than ecosystems composed of indig-

enous species.

Indicators (8) and (9) are related to “naturalness” and

the roles of humans in ecosystems, both of which are philo-

sophically controversial topics. However, most ecologists

would consider that self-organizing, unmanaged ecosystems

composed of native species have greater ecological integrity

than those that are strongly influenced by humans. Examples

of strongly human-dominated systems include agroecosys-

tems, forestry plantations, and urban and suburban areas.

None of these ecosystems can maintain their character in the

absence of management by humans, including large inputs of

energy and nutrients.

Indicators of ecological integrity

Indicators of ecological integrity vary greatly in their

intent and complexity. For instance, certain metabolic indi-

cators have been used to monitor the responses by individuals

and populations to toxic stressors, as when bioassays are

made of

enzyme

systems that respond vigorously to expo-

sures to

dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane

(DDT), penta-

chlorophenols (PCBs), and other

chlorinated hydrocar-

bons

. Other simple indicators include the populations of

endangered species

; these are relevant to the viability of

those species as well as the integrity of the ecosystem of

416

which they are a component. There are also indicators of

ecological integrity at the level of landscape, and even global

indicators relevant to climate change, depletion of strato-

spheric ozone, and

deforestation

.

Relatively simple indicators can sometimes be used to

monitor the ecological integrity of extensive and complex eco-

systems. For example, the viability of populations of spotted

owls (Strix occidentalis) is considered to be an indicator of the

integrity of the old-growth forests in which this endangered

species breeds in the western United States. These forests are

commercially valuable, and if plans to harvest and manage

them are judged to threaten the viability of a population of

spotted owls, this would represent an important challenge to

the integrity of the

old-growth forest

ecosystem.

Ecologists are also beginning to develop composite

indicators of ecological integrity. These are designed as sum-

mations of various indicators, and are analogous to such

economic indices such as the Dow-Jones Index of stock

markets, the Consumer Price Index, and the gross domestic

product of an entire economy. Composite economic indica-

tors of this sort are relatively simple to design, because all

of the input data are measured in a common way (for exam-

ple, in dollars). In

ecology

, however, there is no common

currency among the many indicators of ecological integrity.

Consequently it is difficult to develop composite indicators

that ecologists will agree upon.

Still, some research groups have developed composite

indicators of ecological integrity that have been used success-

fully in a number of places and environmental contexts. For

instance, the ecologist James Karr and his co-workers have

developed composite indicators of the ecological integrity

of aquatic ecosystems, which are being used in modified

form in many places in North America.

In spite of all of the difficulties, ecologists are making

substantial progress in the development of indicators of eco-

logical integrity. This is an important activity, because our

society needs objective information about complex changes

that are occurring in environmental quality, including degra-

dations of indigenous species and ecosystems. Without such

information, actions may not be taken to prevent or repair

unacceptable damages that may be occurring.

Increasingly, it is being recognized that human econo-

mies can only be sustained over the longer term by ecosys-

tems with integrity. Ecosystems with integrity are capable

of supplying continuous flows of such renewable resources

as timber, fish, agricultural products, and clean air and water.

Ecosystems with integrity are also needed to sustain popula-

tions of native species and their natural ecosystems, which

must be sustained even while humans are exploiting the

resources of the

biosphere

.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]