Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dry cask storage

Of all the water on the earth, less than 3% is fresh

water. A lot of water is lost in evaporation, especially in

arid

climates, not only during rainfall but when it is stored in

surface reservoirs. Rainwater or snowmelt that seeps into

below-ground

permeable

rock channels, or aquifers, is

pumped into wells in many communities. High-tech pumps

have contributed to an increased drain on aquifers; if an

aquifer

is pumped too quickly, it collapses, and the ground

above sinks. To increase water bank supplies, some commu-

nities recharge their aquifers by pumping water into them

when they are low.

The only new water introduced into the

hydrologic

cycle

is purified ocean water.

Desalinization

plants are

expensive to build and maintain and often require burning

fossil fuels

or wood to run. Future plans include perfecting

retrieving

solar energy

and

wind energy

.

Currently, farm

irrigation

uses most of the world’s

fresh water supply, but as city populations grow, they are

expected to become the biggest consumers, and urban

con-

servation

measures will become imperative. Some commu-

nities already recycle

wastewater

for small farms and do-

mestic garden use. Drought-causing industrial pollutants

that “freeze” the water supply by rendering it toxic are being

reduced and resolved under federal law. Reduced or low-flow

shower heads and

toilets

are required in new construction in

some states.

Distributing water from more to less abundant supplies

by laying pipes and installing pumps within a state or a

country requires money and management. If water is fed

across state or international boundaries, legal and political

negotiations are necessary.

During severe drought, sociologists find that people

must either adapt, migrate, or die. Death, however, is usually

caused by other factors such as war or poverty, as in the

Sahel, where relief food supplies have been hijacked and

sold at high prices, or where people in remote villages must

walk to the distribution centers.

Some migrations have been permanent, as in the

mi-

gration

to California during the Midwestern

Dust Bowl

in

the 1930s. Others are temporary, as in the Sahel region,

where people migrate in search of food and water, crossing

country lines.

Most people adapt in drought by making the most of

their resources, such as building reservoirs or desalination

plants or laying pipes connecting to more abundant water

supplies. Farmers often invest in high-tech irrigation tech-

niques or alter their crops to grow low-water plants, such

as garbanzo beans.

Drought has also been the inspiration for inventions.

The American West at the turn of the twentieth century

gave rise to numerous rainmakers who used mysterious

chemicals

or noisemakers to attract rain. Most inventions

387

failed or were unreliable, but out of the impetus to make

rain grew silver iodide cloud-seeding, which now effects a

10–15% increase in local rainfall in some parts of the world.

[Stephanie Ocko]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Glantz, M. H., ed. Drought and Hunger in Africa: Denying Famine a Future.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Dry alkali injection

A method for removing

sulfur dioxide

from

combustion

stack gas. A

slurry

of finely ground alkaline material such

as calcium carbonate is sprayed into the

effluent

gases before

it enters the smokestack. The material reacts chemically with

sulfur dioxide to produce a non-hazardous solid product,

such as calcium sulfate, that can then be collected by

filters

or other mechanical means. The technique is called dry

injection because the amount of water in the slurry is adjusted

so that all moisture evaporates while the chemical reactions

are taking place and a dry precipitate results. The use of dry

alkali injection can result in a 90% reduction in the

emission

of sulfur dioxide from a stack. It is more expensive than wet

alkali injection or simply adding crushed limestone to the

fuel, but it is more effective than these techniques and results

in a waste product that is relatively easy to dispose of. See

also Air pollution control

Dry cask storage

Dry cask storage is a method of storing the

radioactive

waste

from nuclear reactors. Dry cask storage refers to the

containers that hold the waste and the system of storing the

waste above ground in containers.

After World War II, nuclear

power plants

began

generating electricity. By the close of the twentieth century,

reactors at

nuclear power

plants generated 20% of the

electricity in the United States. To produce electricity,

ura-

nium

is used as fuel. Each tiny uranium pellet produces

almost as much energy as a ton of

coal

. The pellets are

contained in long metal rods, and these rods are placed in

a fuel assembly that hold from 50 to 300 rods.

The uranium undergoes fission, a process that heats

water and converts it to steam. The steam propels the blades

of a turbine. This in turn spins the shaft of a generator

where electricity is produced.

A large reactor uses 60 assemblies annually, and assem-

blies must be replaced after several years. The waste called

spent fuel is so radioactive that a person standing near an

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dry cleaning

unshielded rod would die within a second. The spent fuel

is also extremely hot. The used fuel rods are taken from the

reactor core and stored in a concrete pool that is lined with

steel. The rods are stored underneath at least 20 ft (6 m) of

water. The spent pool set-up serves as a radiation shield

while water cools the rods.

Spent fuel pools were regarded as temporary storage

facilities. When operators built the first reactors, there were

plans to extract and recycle unused uranium and

plutonium

from the fuel. However, the process would consolidate pluto-

nium into a form that could be used in

nuclear weapons

.

As a result of that consequence, the process was banned in

1977. By that time the United States had produced enough

plutonium to satisfy its own needs for weapons production.

Five years later, Congress passed the Nuclear Waste

Policy Act. Among the issues discussed was where to store

spent fuel because power plants were starting reach to storage

capacity. Congress amended the act in 1987 to designate a

permanent waste disposal site in the

Yucca Mountain

area

of Nevada.

Yucca Mountain had been proposed as a facility that

would open in 1985. However, concerns about a nuclear

explosion and other safety issues led to postponement of the

opening. The opening was shifted to 1989, 1998, 2003,

and 2010.

With no permanent site available, plant operators be-

gan to store spent fuel onsite in dry casks. In 1986, the

United States

Nuclear Regulatory Commission

(NRC)

licensed the first dry storage installation at the Virginia

Electric & Power Company Surry Nuclear Plant in James-

town, Virginia. The utility installed metal casks that were

16 ft (4.9 m) in height. Each dry cask held from 21 to 33

spent fuel assemblies. When filled, each cask weighed 120

tons. Casks were placed vertically on concrete pads that were

3-ft (1 m) thick. Each pad would hold 28 casks.

By 2001, the NRC had approved various dry casks

designs. The container is usually steel. After it is filled, the

container is either bolted or welded shut. The metal casks

are then put inside larger concrete casks to ensure radiation

shielding. Some systems involve placing the steel cask verti-

cally in a concrete vault. In other systems, the container is

placed horizontally in the concrete vault.

Discussions about dry cask safety in the twenty-first

century have centered on the Yucca Mountain proposal. In

May of 2002, the United States House of Representatives

voted to approve the plan. That vote was an override of

Nevada Governor Kenny Guinn’s veto of the plan to send

waste to Yucca. Opponents of the plan like the Nuclear

Information and Resource Service maintained that casks of

waste could not be transported safely by train or truck. In

2002, the facility was expected to cost $58 billion. It was

388

scheduled to open in 2010 and hold a maximum of 77,000

tons of waste.

[Liz Swain]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Murray, Raymond, and Judith Powell, ed. Understanding Radioactive Waste.

Columbus, OH: Battelle Press, 1997.

Saling, James, and Audeen Fentiman. Radioactive Waste Management. Phil-

adelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis, Inc., 2001.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Nuclear Information and Resource Service., 1424 16th Street NW, #404,

Washington, D.C. USA 20036 (202) 328-0002, Fax: (202)462-2183,

Email: nirsnet@nirs.org, <http://www.nirs.org>

United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission., One White Flint North,

11555 Rockville Pike , Rockville, MD USA 20852-2738 (301) 415-7000,

Toll Free: (800) 368-5642, Email: opa@nrc.gov, <http://www.nrc.gov>

Dry cleaning

Dry cleaning is a process of cleaning clothes and fabrics with

solutions that do not contain water. The practice has been

traced back to France where around 1825 turpentine was

used in the cleaning this process. According to Albert R.

Martin and George P. Fulton in Dry cleaning, Technology

and Theory, published in 1958, the tradition passed down

regarding the origins of dry cleaning states that the process

was discovered when “a can of ’camphene,’ a fuel for oil

lamps, was accidentally spilled on a gown and found to

clean it, and this discovery led to the first dry cleaning

establishment.” Because of this, dry cleaning was referred

to as “French cleaning” even into the second half of the

twentieth century.

By the late 1800s, naphtha,

gasoline

,

benzene

, and

benzol—the most common solvent—were being used for

dry cleaning. Fire hazards associated with using gasoline for

dry cleaning prompted the United States Department of

Commerce in March 1928 to issue a standard for dry clean-

ing specifying that a dry cleaning solvent derived from

petro-

leum

must have a minimum flash point (the temperature

at which it combusts) of 100°F (38°C). This was known as

the Stoddard solvent.

The first chlorinated solvent used in dry cleaning was

carbon

tetrachloride. It continued to be used until the 1950s

when its toxicity and corrosiveness were determined to be

hazardous. By the 1930s, the use of trichloroethylene became

common. In the 1990s the chemical was still being used in

industrial cleaning plants and on a limited basis in Europe.

This chemical’s incompatibility with acetate dyes used in

the United States brought about the end of its use in the

United States.

Tetrachloroethylene

replaced other dry

cleaning solvents almost completely by the 1940s and 1950s.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dry deposition

In 1990 about 53% of worldwide demand for tetrachloroeth-

ylene was for dry cleaning, and approximately 75% of all dry

cleaners used it. However, in Japan petroleum-based solvents

continued in use through the 1990s. By the late 1990s,

perchloroethylene (perc or PCE) replaced tetrachloroethy-

lene as the predominant cleaning solvent.

When the United States

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA) issued national regulations to control air

emissions of perc from dry cleaners in September 1993,

environmental groups and consumers began to pay closer

attention to the possible negative impact this chemical could

have on human health. In July 2001, the American Council

on Science and Health issued a report concluding that perc

was not hazardous to humans at the levels most commonly

used in dry cleaning. The report noted that, “Perchloroethyl-

ene has been the subject of close government and public

scrutiny for more than 20 years. But government agencies

in the United States and around the world have not agreed

about the potential of environmental exposure to PCE to

cause adverse health effects, including

cancer

, in humans.”

The findings of this report included the following

items:

O

Inhalation of high levels of PCE and chemically similar

solvents can cause neurological effects such as nausea, head-

ache, and dizziness.

O

High inhaled doses have been linked to changes in blood

chemistry indicating that the liver and kidneys have been

affected.

O

These effects have been seen almost exclusively in workers,

particularly in the dry-cleaning and chemical industries.

O

There have been claims that reproductive difficulties are

associated with occupational exposure to PCE.

O

The claim that PCE is a

carcinogen

(cancer-causing sub-

stance) has received the most public and governmental

attention. Concern has been expressed that environmental

exposures to PCE in outdoor or indoor air and in drinking

water can cause cancer in humans.

O

Results of some epidemiological studies of dry cleaning and

chemical workers exposed to PCE have been interpreted to

suggest a relationship between occupational exposure and

various types of cancer. Careful examination of the way in

which these studies were conducted reveals serious prob-

lems including uncertainties about the amount of PCE to

which people were exposed, failure to take into account

exposure to other

chemicals

at the same time, and failure

to take into account known confounders. Due to these

deficiencies, these studies do not support a link between

PCE and cancer or other adverse effects in humans.

O

The differences between humans and rodents in the

me-

tabolism

and mechanisms of action of PCE make it un-

likely that the carcinogenic effects seen in mice and rats

389

administered high levels of PCE will occur in humans

exposed at environmentally relevant levels.

The environmental activist association

Greenpeace

also issued a report in July 2001, entitled, Out of Fashion

Moving Beyond Toxic Cleaners. This report urged the EPA

to classify perc as a probable human carcinogen. The report

claimed that up to 266 workers’ cancer deaths in New York,

Chicago, Detroit, and San Francisco were linked to perc.

As of 2002, the dry cleaning industry estimates that

approximately 36,000 dry cleaning establishments exist

across the United States, with about 200,000 people em-

ployed in the industry. Perc is used in at least 85% of dry

cleaning shops as the primary solvent. This means that if

perc is found to be a cancer causing chemical, many people,

including both workers in and people who live near dry

cleaning facilities, may be adversely affected.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

International Fabricare Institute. Environmental & Health Issues. 2002.

<http://www.ifi.org/industry>

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. New Regulation Controlling Emis-

sions from Dry Cleaners. May 1994; June 2002. <http://www.epa.gov/

ttnsbap1>

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Dry Cleaning. 2002.

<http://www.osha.gov/SLTC>

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Drycleaning. 2002.

<http://www.cdc.gov/niosh>

American Council on Science and Health. The Scientific Facts about the

Dry-Cleaning Chemical Perc. 2001. <http://www.acsh.org/>

American Council on Science and Health. Science Group States Dry-Cleaning

Chemical Poses No Health Threat to Consumers. July 2001. <http://www.acsh.-

org/>

Martin, Albert; and George Fulton. Drycleaning, Technology and Theory.

New York: Textile Book Publishers, Inc., 1958.

Greenpeace USA. Dry Cleaning Chemical Linked to Hundreds of Deaths,

Warrants EPA Listing as Carcinogen. July 21, 2001. <http://www.green-

peaceuse.org/media/>

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW,

Washington, D.C. USA 20460 (202) 260-2090, , <www.epa.gov>

International Fabricare Institute, 12251 Tech Road, Silver Spring, MD

USA 20904 (301) 622-1900, Fax: (301) 236-9320, Toll Free: (800) 638-

2627, Email: techline@ifi.org, <http://www.ifi.org>

Neighborhood Cleaners Association, 252 West 29th Street, New York,

NY USA 10001 (212) 967-3002, Fax: (212) 967-2240, Email: sales@nca-

i.com, <http://www.nca-i.com>

Dry deposition

A process that removes airborne materials from the

atmo-

sphere

and deposits them on a surface. Dry deposition

includes the settling or falling-out of particles due to the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dryland farming

influence of gravity. It also includes the deposition of gas-

phase compounds and particles too small to be affected by

gravity. These materials may be deposited on surfaces due

to their solubility with the surface or due to other physical

and chemical attractions. Airborne contaminants are re-

moved by both wet deposition, such as rainfall scavenging,

and by dry deposition. The sum of wet and dry deposition

is called total deposition. Deposition processes are the most

important way contaminants such as acidic sulfur com-

pounds are removed from the atmosphere; they are also

important because deposition processes transfer contami-

nants to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Cross-media

transfers, such as transfers from air to water, can have adverse

environmental impacts, and an example of this is how dry

deposition of sulfur and

nitrogen

compounds can acidify

poorly buffered lakes. See also Acid rain; Nitrogen cycle;

Sulfur cycle

Dryland farming

Dryland farming is the practice cultivating crops without

irrigation

(rainfed agriculture). In the United States, the

term usually refers to crop production in low-rainfall areas

without irrigation, using moisture-conserving techniques

such as mulches and fallowing. Non-irrigated farming is

practiced in the Great Plains, inter-mountain, and Pacific

regions of the country, or areas west of the 23.5 in (600

mm) annual precipitation line, where native vegetation was

short

prairie

grass. In some parts of the world dryland

farming means all rainfed agriculture.

In the western United States, dryland farming has

often resulted in severe or moderate wind

erosion

. Alternat-

ing seasons of fallow and planting has left the land susceptible

to both wind and water erosion. High demand for a crop

sometimes resulted in cultivating lands not suitable for long-

time farming, degrading the

soil

measurably.

Conservation tillage

, leaving all or most of the previ-

ous crop residues on the surface, decreases erosion and con-

serves water. Methods used are stubble

mulch

, mulch, and

ecofallow. In the wetter parts of the Great Plains, fallowing

land has given over to annual cropping, or three-year rota-

tions with one year of fallow. See also Arable land; Desertifi-

cation; Erosion; Soil; Tilth

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Anderson, J. R. Risk Analysis in Dryland Farming Systems. Rome: Food

and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1992.

390

Rene

´

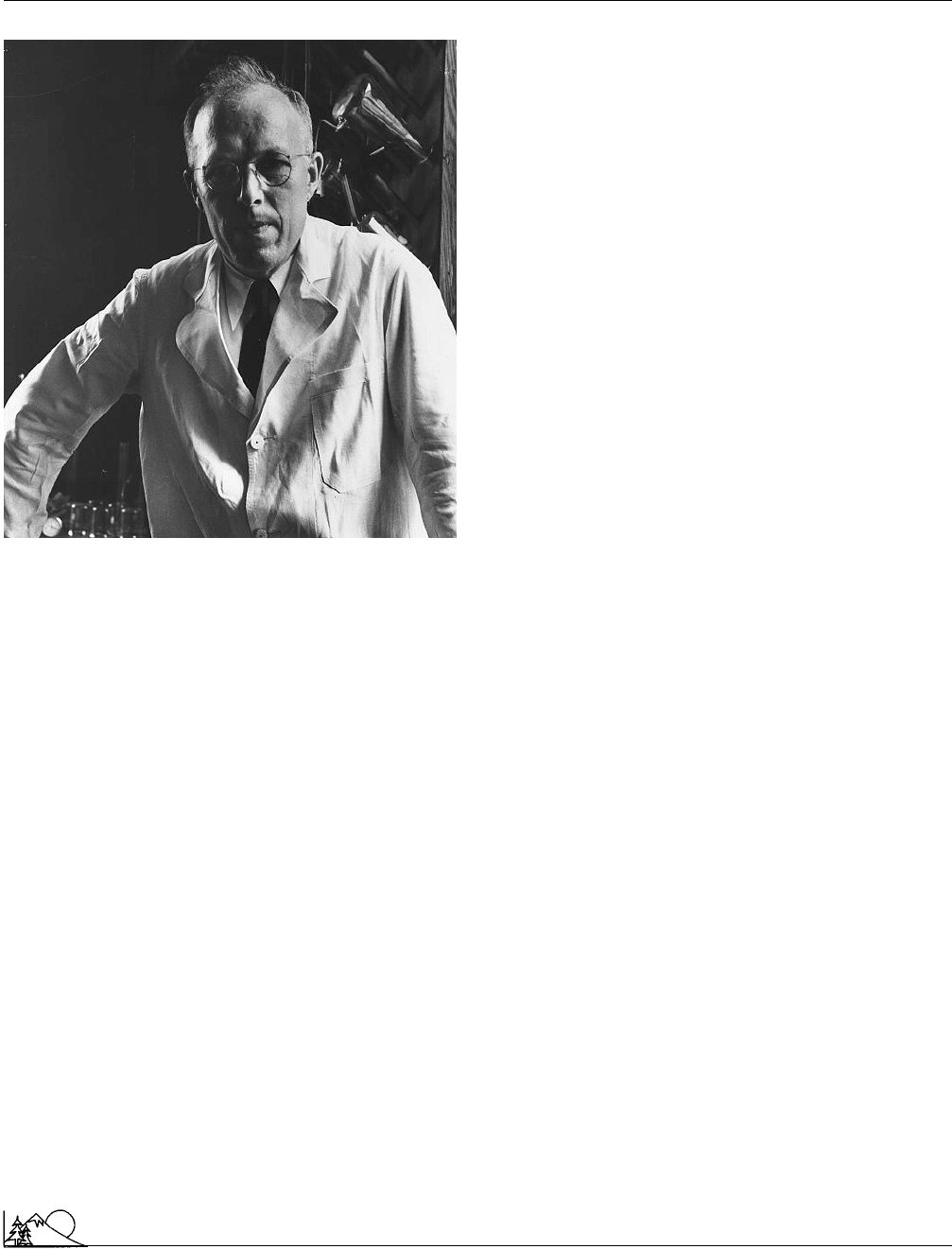

Jules Dubos (1901 – 1982)

French/American microbiologist, ecologist, and writer

Dubos, a French-born microbiologist, spent most of his

career as a researcher and teacher at Rockefeller University

in New York state. His pioneering work in microbiology,

such as isolating the anti-bacterial substance gramicidin from

a

soil

organism and showing the feasibility of obtaining

germ-fighting drugs from

microbes

, led to the development

of antibiotics.

Nevertheless, most people know Dubos as a writer.

Dubos’s books centered on how humans relate to their sur-

roundings, books informed by what he described as “the

main intellectual attitude that has governed all aspects of

my professional life...to study things, from microbes to man,

not per se but in their complex relationships.” That pervasive

intellectual stance, carried throughout his research and writ-

ing, reflected what Saturday Review called “one of the best-

formed and best-integrated minds in contemporary civili-

zation.”

A related theme was Dubos’s conviction that “the total

environment” played a role in human disease. By total

envi-

ronment

, he meant “the sum of the facts which are not only

physical and social conditions but emotional conditions as

well.” Though not a medical doctor, he became an expert

on disease, especially tuberculosis, and headed Rockefeller’s

clinical department on that disease for several years.

“Despairing optimism” also pervaded Dubos’s human-

environment writings, his own title for a column he wrote

for The American Scholar, beginning in 1970. Time magazine

even labeled him the “prophet of optimism:” “My life philos-

ophy is based upon a faith in the immense resiliency of

nature,” he once commented.

Dubos held a lifelong belief that a constantly changing

environment meant organisms, including humans, had to

adapt constantly to keep up, survive, and prosper. But he

worried that humans were too good at adapting, resulting in

both his optimism and his despair: “Life in the technologized

environment seems to prove that [humans] can become

adapted to starless skies, treeless avenues, shapeless build-

ings, tasteless bread, joyless celebrations, spiritless plea-

sures—to a life without reverence for the past, love for the

present, or poetical anticipations of the future.” He stated

that “the belief that we can manage the earth may be the

ultimate expression of human conceit,” but insisted that

nature

is not always right and even that humankind often

improves on nature. As Thomas Berry suggested, “Dubos

sought to reconcile the existing technological order and the

planet’s survival through the

resilience

of nature and

changes in human consciousness.”

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ducks Unlimited

Rene

´

Dubos. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Piel, G., and O. Segerberg, eds. The World of Rene Dubos: A Collection from

His Writings. New York: Henry Holt, 1990.

Ward, B., and R. Dubos. Only One Earth: The Care and Maintenance of a

Small Planet. New York: Norton, 1972.

P

ERIODICALS

Culhane, J. “En Garde, Pessimists! Enter Rene Dubos.” New York Times

Magazine 121 (17 October 1971): 44–68.

Kostelanetz, R. “The Five Careers of Rene Dubos.” Michigan Quarterly

Review 19 (Spring 1980): 194–202.

Ducks Unlimited

Ducks Unlimited (DU) is an international (United States,

Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, and

Australia

), member-

ship organization founded during the depression years in

the United States by a group of sportsmen interested in

waterfowl

conservation

. DU was incorporated in early

1937, and DU (Canada) was established later that spring.

The organization was established to preserve and maintain

waterfowl populations through

habitat

protection and de-

velopment, primarily to provide game for sport

hunting

.

During the

Dust Bowl

of the 1930s, the founding members

of DU recognized that most of the continental waterfowl

391

populations were maintained by breeding habitat in the

wet-

lands

of Canada’s southern prairies in Saskatchewan, Mani-

toba, and Alberta. The organizers established DU Canada

and used their resources to protect the Canadian

prairie

breeding grounds. Cross-border funding has since been a

fundamental component of DU’s operation, although in re-

cent years funds also have been directed to the northern

American prairie states. In 1974 Ducks Unlimited de Mexico

was established to restore and maintain wetlands south of

the U.S.-Mexican border where many waterfowl spend the

winter months.

Throughout most of its existence, DU has funded

habitat restoration projects and worked with landowners to

provide water management benefits on farmlands. But, from

its inception DU has been subject to criticism. Early oppo-

nents characterized it as an American intrusion into Canada

to secure hunting areas. More recently, critics have suggested

that DU defines waterfowl habitat too narrowly, excluding

upland areas where many ducks and geese nest. The group

plans to broaden its focus to encompass preservation of these

upland breeding and nesting areas. Since many of these areas

are found on private land, DU also plans to expand its

cooperative programs with farmers and ranchers. Most com-

monly, however, DU is criticized for placing the interests

of waterfowl hunters above

wildlife management

concerns.

The organization does allow duck hunting on its preserves.

Following the fundamental principle of “users pay,”

duck hunters still provide the majority of DU’s funding. For

that reason DU has not addressed some issues that have a

serious effect on continental waterfowl populations. The

combination of illegal hunting and liberal bag limits is

blamed by some for the continued decline in waterfowl

numbers. DU has not addressed this issue, preferring to

leave management issues to government agencies in the

United States and Canada, while focusing on habitat preser-

vation and restoration. Critics of DU suggest that the organi-

zation will not act on population matters and risk offending

the hunters who provide their financial support.

In North America DU has expanded its scope and

activities to address ecological and

land use

problems

through the work of the North American Waterfowl Man-

agement Plan (NAWMP) and the Prairie CARE (Conser-

vation of Agriculture, Resources and

Environment

) pro-

gram. The wetlands conservation and other habitat projects

addressed in these and similar programs, not only benefit

game

species

, but other

endangered species

of plants

and animals as well. NAWMP (an agreement between the

United States and Canada) alone protects over 5.5 million

acres (2.2 million ha) of waterfowl habitat. In 2002, the

North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA)

granted the DU one million dollars to be put towards a new

wetlands in Ohio.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ducktown, Tennessee

On balance, DU has had a major, positive impact

on North American waterfowl habitat and management.

Millions of acres of wetlands have been protected, enhanced,

and managed in Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

However, the continued decline in waterfowl populations

may require the organization to redirect some of its efforts

to population management and preservation issues.

[David A. Duffus]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Ducks Unlimited, Inc., One Waterfowl Way, Memphis, TN USA 38120

(901) 758-3825, Toll Free: (800) 45DUCKS, <http://www.ducks.org>

Ducktown, Tennessee

Tucked in a valley of the Cherokee

National Forest

,on

the border of Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia,

Ducktown once reflected the beauty of the surrounding Ap-

palachian Mountains. Instead, Ducktown and the valley

known as the

Copper

Basin now form the only

desert

east

of the Mississippi. Mined for its rich copper lode since the

1850s, it had become a vast stretch of lifeless, red-clay hills.

It was an early and stark lesson in the devastation that

acid

rain

and

soil erosion

can wreak on a landscape, one of

the few man-made landmarks visible to the astronauts who

landed on the moon.

Prospectors came to the basin during a gold rush in

1843, but the closest thing to gold they discovered was

copper, and most went home. But by 1850, entrepreneurs

realized the value of the ore, and a new rush began to mine

the area. Within five years, 30 companies had dug beneath

the

topsoil

and made the basin the country’s leading pro-

ducer of copper.

The only way to separate copper from the zinc, iron,

and sulfur present in Copper Basin rock was to roast the

ore at extremely high temperatures. Mining companies built

giant open pits in the ground for this purpose, some as wide

as 600 ft (183 m) and as deep as a 10-story building. Fuel

for these fires came from the surrounding forests. The forests

must have seemed a limitless resource, but it was not long

before every tree, branch, and stump for 50 mi

2

(130 km

2

)

had been torn up and burned. The fires in the pits emitted

great billows of

sulfur dioxide

gas—so thick people could

get lost in the clouds even at high noon—and this gas mixed

with water and oxygen in the air to form sulfuric

acid

, which

is main component in acid rain. Saturated by acidic moisture

and choked by the remaining sulfur dioxide gas and dust,

the undergrowth died and the soil became poisonous to new

plants.

Wildlife

fled the shelterless hillsides. Without root

systems, virtually all the soil washed into the Ocoee River,

392

smothering aquatic life. Open-range grazing of cattle, al-

lowed in Tennessee until 1946, denuded the land of what

little greenery remained.

Soon after the turn of the century, Georgia filed suit

to stop the

air pollution

which was drifting out of this

corner of Tennessee. In 1907, the Supreme Court, in a

decision written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, ruled

in Georgia’s favor, and the sulfur clouds ceased in the Copper

Basin. It was one of the first environmental-rights decisions

in the United States. That same year, the Tennessee Copper

Company designed a way to capture the sulfur fumes, and

sulfuric acid, rather than copper, became the area’s main

product. It remains so today.

Ducktown was the first mining settlement in the area,

and residents now take a curious pride not only in the town’s

history, but in the eerie moonscape of red hills and painted

cliffs that surrounds it. Since the 1930s, Tennessee Copper

Company, the

Tennessee Valley Authority

, and the

Soil

Conservation Service

have worked to restore the land,

planting hundreds of loblolly pine and black locust trees.

Their efforts have met with little success, but new reforesta-

tion techniques such as slow-release

fertilizer

have helped

many new plantings survive. Scientists hope to use the tech-

niques practiced here on other deforested areas of the world.

Ironically, many of the townspeople want to preserve a piece

of the scar, both for its unique beauty and the environmental

lesson of what human enterprise can do to

nature

, as well

as what it can undo. See also Acid waste; Ashio, Japan; Mine

spoil waste; Smelter; Sudbury, Ontario; Surface mining;

Trail Smelter arbitration

[L. Carol Ritchie]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Barnhardt, W. “The Death of Ducktown.” Discover 8 (October 1987):

34-6+.

Dunes and dune erosion

Dunes are small hills, mounds or ridges of wind-blown

soil

material, usually sand, that are formed in both coastal and

inland areas. The formation of coastal or inland dunes re-

quires a source of loose sandy material and dry periods during

which the sand can be picked up and transported by the

wind. Dunes exist independently of any fixed surface feature

and can move or drift from one location to another over

time. They are the result of natural

erosion

processes and

are natural features of the landscape in many coastal areas and

deserts, yet they also can be symptoms of land degradation.

Inland dunes are either an expression of aridity or can be

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dunes and dune erosion

indicators of desertification—the result of long-term land

degradation in dryland areas.

Coastal dunes are the result of marine erosion in which

sand is deposited on the shore by wave action. During low

tide, the beach sand dries and is dislodged and transported

by the wind, usually over relatively short distances. De-

pending on the local

topography

and direction of the pre-

vailing winds, a variety of shapes and forms can develop—

from sand ridges to parabolic mounds. The upper few centi-

meters of coastal dunes generally contain chlorides from salt

spray and wind-blown salt. As a result, attempts to stabilize

coastal dunes with vegetation are often limited to salt-toler-

ant plants.

The occurrence of beaches and dunes together have

important implications for coastal areas. A beach absorbs

the energy of waves and acts as a

buffer

between the sea and

the dunes behind it. Low lying coastlines are best defended

against high tides by consolidated sand dunes. In such cases,

maintaining a wide, high beach that is backed by stable

dunes is desirable.

Engineering structures along coastal areas and the

mouths of rivers can affect the formation and erosion of

beaches and coastal dunes. In some instances it is desirable

to build and widen beaches to protect coastal areas. This

can require the construction of structures that trap littoral

drift, rock mounds to check wave action, and sea walls that

protect areas behind the beach from heavy wave action.

Where serious erosion has occurred, artificial replacement

of beach sands may be necessary. Such methods are expensive

and require considerable engineering effort and the use of

heavy equipment.

The

weathering

of rocks, mainly sandstone, is the

origin of material for inland dunes. However, whether or not

sand dunes form, depends on the vegetative cover condition

and use of the land. In contrast to coastal dunes, that are

often considered to be beneficial to coastal areas, inland

dunes can be indicators of land degradation where the pro-

tective cover of vegetation has been removed as a result of

inappropriate cultivation,

overgrazing

, construction activi-

ties, and so forth. When vegetative cover is absent, soil is

highly susceptible to both water and wind erosion. The two

work together in drylands to create sources of soil that can

be picked up and transported either downwind or down-

stream. The flow of water moves and exposes sand grains

and supplies fresh material that results in deposits of sand

in flood plains and ephemeral

drainage

systems. Before

dunes can develop in such areas, there must be long dry

periods between periodic or episodic sediment-laden flows

of water. Wind erosion occurs where such sand deposits

from water erosion are exposed to the energy of wind, or in

areas that are devoid of vegetative cover.

393

Where sand is the principle size soil particle and where

high wind velocities are common, sand particles are moved

by a process called saltation and creep. Sand dunes form

under such conditions and are shaped by wind patterns over

the landscape. Complex patterns can be formed—the result

of interactions of wind, sand, the ground surface topography,

and any vegetation or other physical barriers that exist. These

patterns can be sword like ridges, called longitudinal dunes,

crescentic accumulations or barchans, turret-shaped

mounds, shallow sheets of sand, or large seas of transverse

dunes. The typical pattern is one of a gradual long slope on

the windward side of the dune, dropping off sharply on the

leeward side.

Exposed sand dunes can move up to 11 yd (10 m)

annually in the direction of the prevailing wind. Such dunes

encroach upon areas, covering farmlands, pasture lands,

irri-

gation

canals, urban areas, railroads and highways. Blowing

sand can mechanically injure and kill vegetation in its path

and can eventually bury croplands or

rangelands

. If left

unchecked, the drifting sand will expand and lead to serious

economic and environmental losses.

Worldwide, dryland areas are those most susceptible

to wind erosion. For example, 22% of Africa north of the

Equator is severely affected by wind erosion as is over 35%

of the land area in the Near East. As a result, inland dunes

represent a significant landscape component in many

desert

regions. For example, dunes represent 28%, 26%, and 38%

of the landscape of the Saharan Desert, Arabian Desert, and

Australia

, respectively (Heathcote 1983). In 1980, Walls

estimated that 1.3 billion hectares of land were covered by

sand dunes globally. Although dunes can be symptoms of

land use

problems, in some areas they are part of a natural

dryland landscape that are considered to be features of beauty

and interest. Sand dune have become popular recreational

areas in parts of the United States, including the Great Sand

Dune National Monument in southern Colorado with its

229-yd (210-m) high dunes that cover a 158-mi

2

(254.4-

km

2

) area, and the Indiana Dunes State Park along the shore

of Lake Michigan.

When dune formation and encroachment represent

significant environmental and economic problems, sand

dune stabilization and control should be undertaken. Dune

stabilization may initially require one or more of the follow-

ing: applications of water, oil, bitumens emulsions, or chemi-

cal stabilizers to improve the cohesiveness of surface sands;

the reshaping of the landscape such as construction of fore-

dunes that are upwind of the dunes, and armoring of the

surface using techniques such as hydroseeding, jute mats,

mulching and asphalt; and constructing fences to reduce

wind velocity near the ground surface. Although sand dune

stabilization is the necessary first step in controlling this

process, the establishment of a vegetative cover is a necessary

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dunes and dune erosion

The dunes of Nags Head, North Carolina. (Photograph by Jack Dermid, National Audubon Society Collection. Photo Researchers

Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

condition to achieve long-term control of sand dune forma-

tion and erosion. Furthermore, stabilization and revegetation

must be followed with appropriate land management that

deals with the causes of dune formation in the first place.

Where dune erosion has not progressed to a seriously de-

graded state, dunes can become reclaimed through natural

regeneration simply by protecting the area against livestock

grazing, all-terrain vehicles, and foot traffic.

Vegetation stabilizes dunes by decreasing wind speed

near the ground and by increasing the cohesiveness of sandy

material by the addition of organic colloids and the binding

action of roots. Plants trap the finer wind-blown soil parti-

cles, which helps improve

soil texture

, and they also im-

prove the

microclimate

of the site, reducing soil surface

temperatures. Upwind barriers or windbreak plantings of

vegetation, often trees or other woody perennials, can be

effective in improving the success of revegetating sand dunes.

They reduce wind velocities, help prevent exposure of plant

roots from the drifting sand, and protect plantings from the

abrasive action of blowing sand. Areas that are susceptible

to sand dune encroachment can likewise be protected by

using fences or windbreak plantings that reduce wind veloci-

394

ties near the ground surface. Because of the severity of sand

dune environments, it can be difficult to find plant

species

that can be established and survive. In addition, any plantings

must be protected against exploitation, for example, from

grazing or fuelwood harvesting.

The expansion of sand dunes resulting from

desertifi-

cation

not only represent environmental problems, but they

also represent serious losses of productive land and a financial

hardship for farmers and others who depend upon the land

for their livelihood. Such problems are particularly acute in

many of the poorer dryland countries of the world and de-

serve the attention of governments, international agencies,

and nongovernmental organizations who need to direct their

efforts toward the causes of soil erosion and dune formation.

[Kenneth N. Brooks]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brooks, K.N., P.F. Folliott, H. M. Gregersen and L. F. DeBano. Hydrology

and the Management of Watersheds. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univer-

sity Press, 1997.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dust Bowl

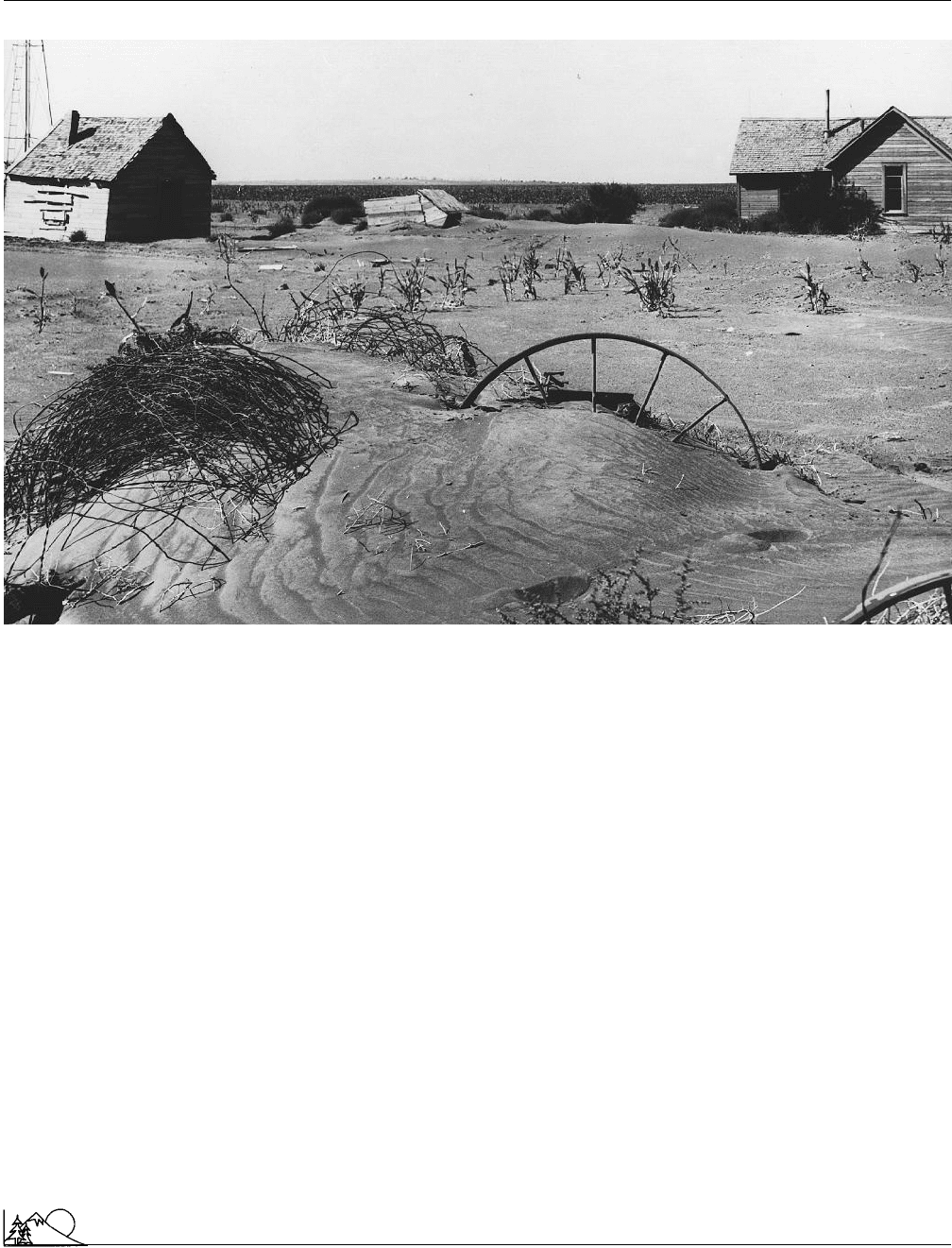

The effects of the Oklahoma dust bowl. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by permission.)

Folliott, P. F., K. N. Brooks, H.M. Gregersen and A.L. Lundgren. Dryland

Forestry—Planning and Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Sand

Dune Stabilization, Shelterbelts, and Afforestation in Dry Zones. Rome: FAO

Conservation Guide 10, 1985.

Dust Bowl

“Dust Bowl” is a term coined by a reporter for the Washington

(D.C.) Evening Star to describe the effects of severe wind

erosion

in the Great Plains during the 1930s, caused by

severe

drought

and lack of

conservation

practices.

For a time after World War I, agriculture prospered

in the Great Plains. Land was rather indiscriminantly plowed

and planted with cereals and row crops. In the 1930s, the

total cultivated land in the United States increased, reaching

530 million acres (215 million ha), its highest level ever.

Cereal crops, especially wheat, were most prevalent in the

Great Plains. Summer fallow (cultivating the land, but only

planting every other season) was practiced on much of the

land. Moisture, stored in the

soil

during the fallow (un-

cropped) period, was used by the crop the following year.

395

In a process called dust

mulch

, the soil was frequently clean

tilled to leave no crop residues on the surface, control weeds,

and, it was thought at the time, preserve moisture from

evaporation. Frequent cultivation and lack of crop canopy

and residues optimized conditions for wind erosion during

the droughts and high winds of the 1930s.

During the process of wind erosion, the finer particles

(

silt

and clay) are removed from the

topsoil

, leaving coarser-

textured sandy soil. The fine particles carry with them higher

concentrations of organic matter and plant nutrients, leaving

the remaining soil impoverished and with a lower water

storage capacity. Wind erosion of the Dust Bowl reduced

the productivity of affected lands, often to the point that

they could not be farmed economically.

While damage was particularly severe in Texas, Okla-

homa, Colorado, and Kansas, erosion occurred in all of

the Great Plains states, from Texas to North Dakota and

Montana, even into the Canadian

Prairie

Provinces. The

eroding soil not only prevented the growth of plants, it

uprooted established ones.

Sediment

filled fence rows,

stream channels, road ditches, and farmsteads. Dirt coated

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dust Bowl

the insides of buildings. Airborne dust made travel difficult

because of decreased

visibility

; it also impaired breathing

and caused

respiratory diseases

.

Dust from the Great Plains was carried high in the

air and transported as far east as the Atlantic seaboard. In

places, 3–4 in (7–10 cm) of topsoil was blown away, forming

dunes

15–20 ft (4.6–6.1 m) high where the dust finally came

to rest. In a 20-county area covering parts of southwestern

Kansas, the Oklahoma strip, the Texas Panhandle, and

southeastern Colorado, a soil-erosion survey by the

Soil

Conservation Service

showed that 80% of the land was

affected by wind erosion, 40% of it to a serious degree.

The droughts and resultant wind erosion of the 1930s

created widespread economic and social problems. Large

numbers of people migrated out of the Dust Bowl area during

the 1930s. The

migration

resulted in the disappearance of

many small towns and community services such as churches,

schools, and local units of government.

Following the disaster of the Dust Bowl, the 1940s

saw dramatically improved economic and social conditions

with increased precipitation and improved crop prices. Grad-

ually, changes in farming practices have also taken place.

Much of the severely damaged and marginal land has been

396

returned to grass for livestock grazing. Non-detrimental till-

age and management practices, such as

conservation tillage

(stubble mulch, mulch, and residue tillage); use of tree, shrub,

and grass windbreaks; maintenance of crop residues on the

soil surface; and better machinery have all contributed to

improved soil conditions. Annual cropping or a three-year

rotation of wheat-sorghum-fallow has replaced the alternate

crop-fallow practice in many areas, particularly in the more

humid areas of the West.

While the extreme conditions of drought and land

mismanagement of the Dust Bowl years have not been re-

peated since the 1930s, wind erosion is still a serious problem

in much of the Great Plains. According to the

Soil Conser-

vation

Service, the states with the most serious erosion

per unit area in 1982 were Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and

Montana. See also Arable land; Desertification; Overgrazing;

Soil eluviation; Tilth; Water resources

[William E. Larson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hurt, R. D. The Dust Bowl: An Agricultural and Social History. Chicago:

Nelson-Hall, 1981.