Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Grizzly bear

A grizzly bear (

Ursus arctos

). (Reproduced by permission.)

February, or March, and are small (less than 1 lb/0.45 kg)

and helpless. They remain in the den for three or four months

before emerging, and stay with their mother for one and a

half to four years. The age at which a female first reproduces,

litter size, and years between litters are determined by nutri-

tion, which induces females to establish foraging territories

which exclude other females. These territories range from

10–75 mi

2

(26–194 km

2

). Males tend to have larger ranges

extending up to 400 mi

2

(1,036 km

2

) and incorporate the

territories of several females. Young females, however, often

stay within the range of their mother for some time after

leaving her care, and one case was reported of three genera-

tions of female grizzly bears living within the same range.

Grizzly bear populations have been decimated over

much of their original range.

Habitat

destruction and

hunt-

ing

are the primary factors involved in their decline. The

North American population, particularly in the lower 48

states, has been extremely hard hit. Grizzly bears numbered

near 100,000 in the lower 48 states as little as 180 years ago,

but, today, fewer than 1,000 remain on less than 2% of their

original range. This population has been further fragmented

into seven small, isolated populations in Washington, Idaho,

677

Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. This decline and frag-

mentation makes their potential for survival tenuous. The

U. S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

considers the grizzly bear

to be threatened in the lower 48 states.

Little has been done to protect this declining species

in the lower 48 states. In 1999 it was agreed to begin

slowly reintroducing grizzlies into the 1.2 million acre

(49,000 ha) area of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness on

the border of Idaho and Montana. Unfortunately, the

project was put on hold as of 2001 due to unfounded

fear of the animal. Habitat loss due to timbering, road

building, and development in this region is still a major

problem and will continue to impact these threatened

populations of bears.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Nowak, R. M., ed. Walker’s Mammals of the World 5th ed. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Groundwater

P

ERIODICALS

“Interior Department Caves in to Grizzly Bear Scare.” USA Today, August

6, 2001.

O

THER

Craighead Environmental Research Institute. [cited May 2002]. <http://

www.grizzlybear.org>.

“New Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan: Bad News for Bears.” Wild Forever, 1993.

Groundwater

Groundwater occupies the void space in a geological strata.

It is one element in the continuous process of moisture

circulation on Earth, termed the

hydrologic cycle

.

Almost all groundwater originates as surface water.

Some portion of rain hitting the earth runs off into streams

and lakes, and another portion soaks into the

soil

, where it

is available for use by plants and subject to evaporation back

into the

atmosphere

. The third portion soaks below the

root zone and continues moving downward until it enters

the groundwater. Precipitation is the major source of

groundwater. Other sources include the movement of water

from lakes or streams and contributions from such activities

as excess

irrigation

and

seepage

from canals. Water has

also been purposely applied to increase the available supply

of groundwater. Water-bearing formations called aquifers

act as reservoirs for storage and conduits for transmission

back to the surface.

The occurrence of groundwater is usually discussed by

distinguishing between a

zone of saturation

and a zone of

aeration

. In the zone of saturation the pores are entirely

filled with water, while the zone of aeration has pores that

are at least partially filled by air. Suspended water does occur

in this zone. This water is called vadose, and the zone of

aeration is also known as the

vadose zone

. In the zone of

aeration, water moves downward due to gravity, but in the

zone of saturation it moves in a direction determined by the

relative heights of water at different locations.

Water that occurs in the zone of saturation is termed

groundwater. This zone can be thought of as a natural storage

area of

reservoir

whose capacity is the total volume of the

pores of openings in rocks.

An important exception to the distinction between

these zones is the presence of ancient sea water in some

sedimentary formations. The pore spaces of materials that

have accumulated on an ocean floor, which has then been

raised through later geological processes, can sometimes con-

tain salt water. This is called connate water.

Formations or strata within the saturated zone from

which water can be obtained are called aquifers. Aquifers

must yield water through

wells

or springs at a rate that can

serve as a practical source of water supply. To be considered

678

an

aquifer

the geological formation must contain pores or

open spaces filled with water, and the openings must be

large enough to permit water to move through them at a

measurable rate. Both the size of pores and the total pore

volume depends on the type of material. Individual pores

in fine-grained materials such as clay, for example, can be

extremely small, but the total volume is large. Conversely,

in coarse material such as sand, individual pores may be

quite large but total volume is less. The rate of movement

from fine-grained materials, such as clay, will be slow due

to the small pore size, and it may not yield sufficient water

to wells to be considered an aquifer. However, the sand is

considered an aquifer even though they yield a smaller vol-

ume of water because, they will yield water to a well.

The

water table

is not stationary but moves up or

down depending on surface condition such as excess precipi-

tation,

drought

, or heavy use. Formations where the top of

the saturated zone or water table define the upper limit of

the aquifer are called unconfined aquifers. The hydraulic

pressure at any level with an aquifer is equal to the depth

from the water table, and there is a type known as a water-

table aquifer, where a well drilled produces a static water

level which stands at the same level as the water table.

A local zone of saturation occurring in an aerated zone

separated from the main water table is called a perched water

table. These most often occur when there is an impervious

strata or significant particle-size change in the zone of aera-

tion which causes the water to accumulate. A confined aqui-

fer is found between impermeable layers. Because of the

confining upper layer, the water in the aquifer exists within

the pores at pressures greater than the atmosphere. This is

termed an artesian condition and gives rise to an

artesian

well

.

Groundwater has always been an important resource,

and it will become more so in the future as the need for good

quality water increases due to urbanization and agricultural

production. It has recently been estimated that 50% of the

drinking water in the United States comes from ground-

water; 75% of the nation’s cities obtain all or part of their

supplies from groundwater, and rural areas are 95% depen-

dent upon it. For these reasons, it is widely believed that

every precaution should be taken to protect groundwater

purity. Once contaminated, groundwater is difficult, expen-

sive, and sometimes impossible to clean up. The most preva-

lent sources of contamination are waste disposal, the storage,

transportation

and handling of commercial materials, min-

ing operations, and nonpoint sources such as agricultural

activities. See also Agricultural pollution; Aquifer restoration;

Contaminated soil; Drinking water supply; Safe Drinking

Water Act; Water quality; Water table draw-down

[James L. Anderson]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Groundwater pollution

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Collins, A. G., and A. I. Johnson, eds. Ground-Water Contamination: Field

Methods. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing and Materials, 1988.

Davis, S. N., and R. J. M. DeWiest. Hydrogeology. New York: Wiley, 1966.

Fairchild, D. M. Ground Water Quality and Agricultural Practices. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1988.

Freeze, R. A., and J. A. Cherry Ground Water. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 1979.

Ground Water and Wells. St. Paul: Edward E. Johnson, 1966.

Groundwater monitoring

Monitoring

groundwater

quality and

aquifer

conditions

can detect contamination before it becomes a problem. The

appropriate type of monitoring and the design of the system

depends upon

hydrology

,

pollution

sources, and the popu-

lation density and

climate

of the region. There are four

basic types of groundwater monitoring systems: ambient

monitoring, source monitoring, enforcement monitoring,

and research monitoring.

Ambient monitoring involves collection of background

water quality

data for specific aquifers as a way to detect

and evaluate changes in water quality. Source monitoring is

performed in an area surrounding a specific, actual, or poten-

tial source of contamination such as a

landfill

or spill site.

Enforcement monitoring systems are installed at the direc-

tion of regulatory agencies to determine or confirm the origin

and concentration gradients of contaminants relative to regu-

latory compliance. Research monitoring

wells

are installed

for detection and assessment of cause and effect relationships

between groundwater quality and specific

land use

activities.

See also Aquifer restoration; Contaminated soil; Drinking-

water supply; Hazardous waste siting; Leaching; Water qual-

ity standards

Groundwater pollution

When contaminants in

groundwater

exceed the levels

deemed safe for the use of a specific

aquifer

use the ground-

water is considered polluted. There are three major sources

of groundwater

pollution

. These include natural sources,

waste disposal activities, and spills, leaks, and

nonpoint

source

activities such as agricultural management practices.

All groundwater naturally contains some dissolved

salts or minerals. These salts and minerals may be leached

from the

soil

and from the aquifer materials themselves and

can result in water that poses problems for human consump-

tion, is considered polluted, or does not meet the

secondary

standards

for

water quality

. Natural minerals or salts that

679

may result in polluted ground water include chloride, nitrate,

fluoride, iron and sulfate.

There are currently no feasible methods for the large-

scale disposal of waste that do not have the potential for

serious pollution of the

environment

, and there are a num-

ber of waste-disposal practices the specifically threaten

groundwater. These include activities which range from sep-

arate

sewage treatment

systems for individual residences,

used by 30% of the population in the United States, to

the storage and disposal of industrial wastes. Many of the

problems posed by industrial waste arise from the use of

surface storage facilities that rely on evaporation for disposal.

These facilities are also known as

discharge

ponds, and

there are other types in which waste is treated to standards

suitable for discharge to surface water. But in the use of

both facilities the potential exists for the movement of con-

taminants into groundwater. Many of the numerous sanitary

landfills in the country are in the same situation. Water

moving down and away from these sites into groundwater

aquifers carries with it a variety of

chemicals

leached from

the material deposited in the landfills. The liquid that moves

out of landfills is called leachate.

Agricultural practices also contribute to groundwater

pollution, and there have been increases in nitrate concentra-

tions and low-level concentrations of pesticides. For control

of groundwater pollution, one of the most important agricul-

tural practices is the management of

nitrogen

from all

sources--fertilizer, nitrogen fixing plants, and

organic

waste

. Once nitrogen is in the nitrate form it is subject to

leaching

, so it is important that the amount applied not

exceed the crops’ ability to use it. At the same time crops

need adequate nitrogen to obtain high yields, and a good

balance must be maintained. Low-level

pesticide

contami-

nation occurs in areas where aquifers are sensitive to surface

activity, particularly areas of shallow aquifers beneath rapidly

permeable

soils, and regions of “karst”

topography

where

deep and wide range pollution can occur due to fractures in

the bedrock.

Except in cases of

deep-well injection

waste or sub-

stances contained in sanitary landfills, most contaminants

move from the land surface to aquifers. The water generally

moves through an unsaturated zone, in which biological

and chemical processes may act to degrade or change the

contaminant. Plant uptake can also act to reduce some of

the pollution. Once in the aquifer, how the contaminant

moves with the water will depend the solubility of the com-

pound, and the speed of contamination will depend on how

fast water moves through the aquifer. Chemical and biologi-

cal degradation of contaminants can occur in the aquifer,

but usually at a slower rate than it does on the surface due

to lower temperatures, less available oxygen, and reduced

biological activity. In addition aquifer contaminants exist in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Groundwater pollution

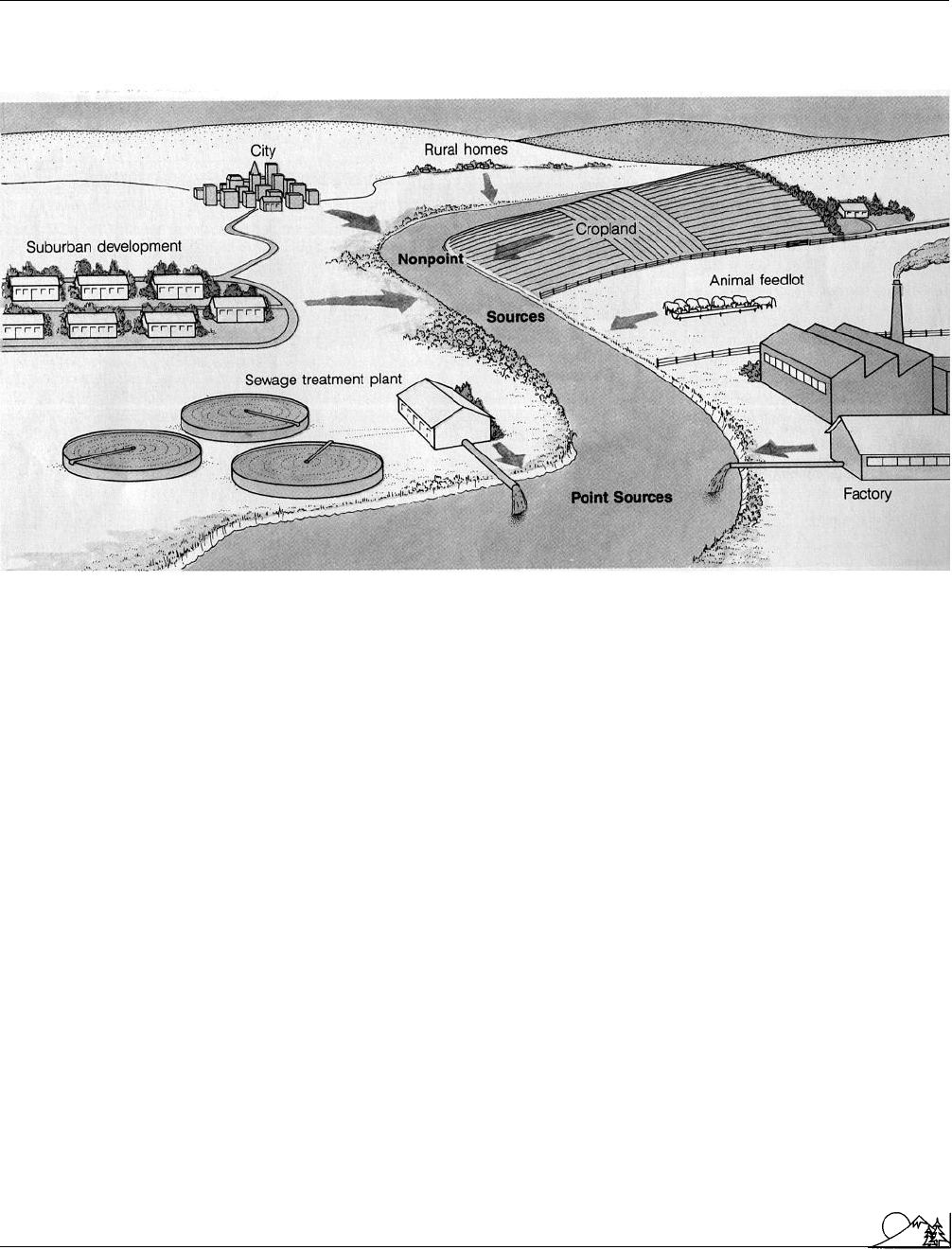

Sources of groundwater pollution. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

lower concentrations, diluted by the large water volume.

Most pollution remains relatively localized in aquifers, since

movement of the contaminants usually occurs in plumes that

have definite boundaries and do not mix with the rest of

the water. This does provide an advantage for isolation and

treatment.

The types of chemicals that pollute groundwater are

as varied as their sources. They range from such simple

inorganic materials as nitrate from fertilizers, septic tanks,

and

feedlots

, chloride from high salt, and

heavy metals

such as chromium from metal plating processes, to very

complex organic chemicals used in manufacturing and

household cleaners.

One of the main criteria in judging risk is public health.

Acute effects

from immediate exposure to a concentrated

product is often well documented, but little written evidence

exists to link physiological effects with long-term chronic

exposure. About all that is available are epidemiological data

that suggest possible effects, but are by no means conclusive.

Environmental effects are even less well understood, but

some have suggested that the best way to determine the

potential danger is to look at how long a substance persists.

680

Those that remain the longest are most likely to pose long-

term risks.

The most efficient way to protect groundwater is to

limit activities in recharge areas. For confined aquifers it

may be possible to control activities that can result in pollu-

tion, but this is extremely difficult for unconfined aquifers

which are essentially open systems and subject to effects

from any land activity. In areas of potential salt-water intru-

sion excess pumping can be regulated, and this can also be

done where water is being used for

irrigation

faster than the

recharge rate, so that the water is becoming saline. Another

important activity for the protection of groundwater is the

proper sealing of all

wells

that are not currently being used.

Classification of aquifers according to their predomi-

nant use is another management tool now employed in a

number of states. This establishes water-quality goals and

standards for each aquifer, and means that aquifers can be

regulated according to their major use. This protects the

most valuable aquifers, but leaves the problem of predicting

future needs. Once an aquifer is contaminated, it is very

expensive if not impossible to restore, and this management

tool may have serious drawbacks in the future.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Growth limiting factors

In rural areas of the United States, 95% of the popula-

tion draws their drinking water from the groundwater supply.

With a growing population, continued industrialization, and

increasing agricultural reliance on the use of chemicals, many

believe it is now more important than ever to protect ground-

water. Contamination problems have been encountered in

every state, but prevention is far more efficient and effective

than restoration after damage has been done. Prevention

can be achieved through regional planning and enforcement

of state and federal regulations. See also Agricultural pollu-

tion; Aquifer restoration; Contaminated soil; Drinking-

water supply; Feedlot runoff; Groundwater monitoring;

Hazardous waste site remediation; Hazardous waste siting;

Heavy metals and heavy metal poisoning; Waste manage-

ment; Water quality; Water quality standards; Water

treatment

[James L. Anderson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Freeze, R. A., and J. A. Cherry. Ground Water. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 1979.

Pye, V. I., R. Patrick, and J. Quarles. Ground Water Contamination in the

United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983.

P

ERIODICALS

Hallberg, G. R. “From Hoes to Herbicides: Agriculture and Groundwater

Quality.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation (November-December

1986): 358–59.

Growth curve

A graph in which the number of organisms in a population

is plotted against time. Such curves are amazingly similar

for populations of almost all organisms from bacteria to

human beings and are considered characteristic of popula-

tions.

Growth curves typically have a sigmoid or S-shaped

curve. When a few individuals enter a previously unoccupied

area, growth is at first slow during the positive acceleration

phase. The growth then becomes rapid and increases expo-

nentially, called the logarithmic phase. The growth rate

eventually slows down as environmental

resistance

gradu-

ally increases; this phase is called the negative acceleration

phase. It finally reaches an equilibrium or saturation level.

The final stage of the growth curve is termed the

carrying

capacity

of the

environment

.

A good example of a species’ growth curve is demon-

strated by the sheep population in Tasmania. Sheep were

introduced into Tasmania in 1800. Careful records of their

numbers were kept, and by 1850 the sheep population had

681

reached 1.7 million. The population remained more or less

constant at this carrying capacity for nearly a century.

The figures used to plot a growth curve—time and

the total number in the population—vary from one

species

to another, but the shape of the growth curve is similar for

all populations. Once a population has become established

in a certain region and has reached the equilibrium level,

the numbers of individuals will vary from year to year de-

pending on various environmental factors. Comparing these

variations for different species living in the same region is

helpful to scientists who manage

wildlife

areas or who track

factors that affect populations.

For example, a study of the population variations of

the snowshoe hare and the lynx (Lynx canadensis) in Canada

is a classic example of species interaction and interdepen-

dence. The peak of the hare population comes about a year

before the peak of the lynx population. Since the lynx feeds

on the hare, it is obvious that the lynx cycle is related to the

hare cycle. This leads to a decline in the population of hares

and secondarily to a decline in the lynx population. This

permits the plants to recover from the overharvesting by the

hares, and the cycle can begin again.

Growth curves are just one of the characteristics of

populations. Other characteristics that are a function of the

whole group and not of the individual members include

population density, birth rate, death rate, age distribution,

biotic potential, and rate of dispersion. See also Population

growth

[Linda Rehkopf]

Growth, exponential

see

Exponential growth

Growth limiting factors

There are a number of essential conditions which all organ-

isms, both plants and animals, require to grow. These are

known as growth factors. Plants, for example, require sun-

light, water, and

carbon dioxide

in order to perform

photo-

synthesis

. They require nutrients such as

nitrogen

,

phos-

phorus

, and various trace elements in order to form tissues.

The

environment

in which the plant is growing does not

contain a unlimited supply of these growth factors. When

one or more of them is present in levels or concentrations

low enough to constrain the growth of the plant, it is known

as a growth limiting factor. The rate or magnitude of the

growth of any organism is controlled by the growth factor

that is available in the lowest quantities. This concept is

analogous to the saying that a chain is only as strong as its

weakest link.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Guano

These factors limit

population growth

. If they did

not exist, a population could increase exponentially, limited

only by its own intrinsic lifespan. Growth limiting factors

are essential to the traditional concept of

carrying capacity

,

which rests on the assumption that the available resources

limit the population that can be sustained in that area. Ad-

vances in technology have enabled people to increase the

carrying capacity in certain areas by manipulating the growth

limiting factors. Perhaps the best example of this is the use

of fertilizers on farmland.

In the field of population

ecology

, identifying growth

limiting factors is part of establishing the constraints and

pressures on populations and predicting growth in various

conditions. Algal growth in New York Harbor provides an

example of the importance of identifying growth limiting

factors. In New York Harbor, several billion gallons of un-

treated

wastewater

are released daily, bringing enormous

quantities of nutrients and suspended solids into the water.

Algae in the harbor take advantage of the

nutrient

loads

and grow more than they would under nutrient-poor condi-

tions. At the same time, however, the suspended solids and

silts brought into harbor cause the water to become very

turbid, limiting the amount of sunlight that penetrates it.

Sunlight is rarely a growth limiting factor for algae; nutrients

are usually what limits their growth, but in this case nutrients

are in excess supply. This means that if

pollution control

in the harbor ever results in control of the turbidity in the

water, there will probably be a sharp increase in the growth

of algae.

Consideration of growth limiting factors is also very

important in the field of

conservation biology

and

habitat

protection. If the goal is to protect a bird such as the heron,

which may feed on fish from a lake and nest in upland trees

nearby, limiting factors must be taken into account not only

for the growth of the individual but also for the population.

Conservation

efforts must not be directed only toward en-

suring there are enough fish in the lake. Enough trees must

also be left uncut and undisturbed for nesting in order to

address all of the growth requirements for the population.

Regardless of how abundant the fish are, the number of

herons will only grow to the extent allowed by the number

of available nesting sites.

Environmentalists use growth limiting factors to dis-

tinguish between undisturbed ecosystems and unstable or

stressed systems. In an

ecosystem

that has been distressed

or disturbed, the nature of growth limiting factors changes,

and these changes are often human-induced, as they are in

New York Harbor. Though the change in circumstances

may not always appear negative in impact, it still represents

a shift away from the original balance, and it may have

effects on other

species

or lead to subtle long-term changes

in the system. Any cleanup or management strategy must

682

use these new growth limiting factors to identify the nature

of the imbalance that has occurred and develop a procedure

to restore the system to its original condition.

Growth limiting factors are extensively used in the

field of

bioremediation

, in which

microbes

are used to

clean up environmental contaminants by breakdown and

decomposition

.

Oil spills

are a good example. Bacteria that

can break down and degrade oils are naturally present in

small quantities in

soil

, but under normal conditions their

growth is limited by both the availability of essential nutri-

ents and the availability of oil. In the event of an oil spill

on land, the only growth limiting factor for these bacteria

is nutrients. Bioremediation scientists can add nitrogen and

phosphorus to the soil in these circumstances to stimulate

growth, which increases degradation of the oil. Techniques

such as these, which use naturally occurring bacterial popula-

tions to control contamination, are still in development; they

are most useful when the contaminants are present in high

concentrations and confined to a limited area. See also Algal

bloom; Decline spiral; Ecological productivity; Exponential

growth; Food chain/web; Restoration ecology

[Usha Vedagiri and Douglas Smith]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Mayer, G. Ecological Stress and the New York Bight: Science and Management.

Columbia, SC: Estuarine Research Federation, 1982.

Smith, R. L. Ecology and Field Biology. New York: Harper and Row Publish-

ers, 1980.

Growth, logistic

see

Logistic growth

Growth, population

see

Population growth

Grus americana

see

Whooping crane

Guano

Manure created by flying animals that is deposited in a

central location because of nesting habits. Guano can occur

in caves from

bats

or in nesting grounds where large popula-

tions of birds congregate. Guano was frequently used as a

source of

nitrogen fertilizer

prior to the time when nitrogen

fertilizer was commercially manufactured from

natural gas

.

See also Animal waste

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Guinea worm eradication

Guinea worm eradication

In 1986, the world health community began a campaign to

eliminate the guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis) from

the entire world. If successful, this will be only the second

global disease ever completely eradicated (smallpox, which

was abolished in 1977 was first), and the only time that a

human parasite will have been totally exterminated world-

wide. Known as the fiery serpent, the guinea worm has been

a terrible scourge in many tropical countries. Dracunculiasis

(pronounced dra-KUNK-you-LIE-uh-sis) or guinea worm

disease starts when people drink stagnant water contami-

nated with tiny copepod water fleas (called cyclops) con-

taining guinea worm larvae. Inside the human body, the

worms grow to as long as 3 ft (1 m). After a year of migrating

through the body, a threadlike adult worm emerges slowly

through a painful skin blister. Most worms come out of the

legs or feet but they can appear anywhere on the body. The

eight to 12 weeks of continuous emergence are accompanied

by burning pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting. Many victims

bathe in a local pond or stream to soothe their fever and

pain. When the female worm senses water, she releases tens

of thousands of larvae, starting the cycle once again. Once

the worms become established in local ponds, infections

among people living nearby are at high risk for further infec-

tions.

As the worm emerges from the wound, it can be rolled

around small stick and pulled out a few centimeters each

day. Sometimes the entire worm can be extracted in a few

days, but the process usually takes weeks. Unfortunately, if

you pull too fast and the worm breaks off, the part left in

your body can die and fester, leading to serious secondary

infections. If the worm comes out through a joint, permanent

crippling can occur. There is no cure for guinea worm disease

once the larvae are ingested. There is no vaccine, and having

been infected once doesn’t give you immunity. Many people

in affected villages suffer the disease repeatedly year after

year. The only way to break the cycle is through behavioral

changes. Community health education, providing clean

water from

wells

or by filtering or boiling drinking water,

eliminating water fleas by chemical treatment, and teaching

infected victims to stay out of drinking supplies are the only

solutions to this dreadful problem.

Although people rarely die as a direct effect of the

parasite, the social and economic burden at both the individ-

ual and community level is great. During the weeks that

worms are emerging, victims usually are unable to work or

carry out family duties. This debilitation often continues for

several months after worms are no longer visible. In severe

cases, arthritis-like conditions can develop in infected joints,

and the patient may be permanently crippled.

683

When the eradication campaign was started in 1986,

guinea worms were endemic to 16 countries in sub-Saharan

Africa as well as Yemen, India, and Pakistan. Every year

about 3.5 million people were stricken and at least 100

million people were at risk. With the leadership of former

U.S. President Jimmy Carter, a consortium of agencies, insti-

tutions, and organizations—the World Health Organization

(WHO), UNICEF, the United Nations Development Pro-

gram (UNDP), the

World Bank

, bilateral aid agencies, and

the governments of many developed countries—banded to-

gether to fight this disease. Although complete success has

not yet occurred, encouraging progress has been made. Al-

ready the guinea worm infections are down more than 96%.

Pakistan was the first formerly infested country to be declared

completely free of these

parasites

. Infection rates in Kenya,

Senegal, Cameroon, Chad, India, and Yemen are down

below 100 cases per year. More than 80% of all remaining

cases occur in Sudan, where civil war, poverty,

drought

, and

governmental

resistance

to outside aid have made treatment

difficult.

An encouraging outcome of this crusade is the demon-

stration that public health education and community organi-

zation can be effective, even in some of the poorest and most

remote areas. Village-based health workers and volunteers

conduct disease surveillance and education programs,

allowing funds and supplies to be distributed in an efficient

manner. Once people understand how the disease spreads

and what they need to do to protect themselves and their

families, they do change their behavior. A great advantage

of this community health approach is educating villagers

about the importance of proper

sanitation

and clean drink-

ing water is effective not only against dracunculiasis, but

also can help eliminate

malaria

, shistosomiasis, and many

other water-borne diseases.

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

O

THER

The Carter Center. Eradicating Guinea Worm Disease. 2002 [cited July 9,

2002]. <http://www.cartercenter.org/healthprograms>.

Center for Disease Control. Fact Sheets: Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm Dis-

ease). January 2001 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/

spb/mnpages/dispages/dracuculiasis.html>.

UNICEF. Guinea Worm in Retreat. March/April 1995 [cited July 9, 2002].

<http://www.unicef.org/pon95/heal0013.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Carter Center, One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway, Atlanta, GA

USA 30307 Email: carterweb@emory.edu, http://www.cartercenter.org

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gulf War syndrome

Gulf War syndrome

Approximately 697,000 U.S. service members were deployed

to the Persian Gulf from January to March 1991 as part of

a multinational effort to stop Iraq’s attack against Kuwait.

And while the war itself was short, a long battle has been

taking place ever since by veterans, the government and

scientists to determine what has caused “Gulf War Syn-

drome,” a mysterious collection of symptoms reported by as

many as 70,000 U.S. men and women who served in the

war. They are joined by British veterans in their health

complaints, and in smaller numbers by Canadians, Czechs,

and Slovaks.

Gulf War Syndrome is a complex array of symptoms,

including chronic fatigue, rashes, headaches, diarrhea, sleep

disorders, joint and muscle pain, digestive problems, memory

loss, difficulty concentrating, and depression. A small per-

centage of veterans have had babies born with twisted limbs,

congestive heart failure, and missing organs. The veterans

blamed these abnormalities on their service in the Gulf. The

U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) has also

found high rates for brain and nervous system cancers among

these veterans, up to seven to 14 times higher than among

the general population, depending on the age group. Consid-

ering that most soldiers and veterans are younger and in

better physical shape than the general population, researchers

find such figures more than surprising.

Collectively, these ailments suggest that neurological

processes may have been altered, or immune systems dam-

aged. While no single cause has been identified, various

analyses of the Gulf War experience point to low-level expo-

sure of chemical weapons, combined with other environmen-

tal and medical factors, as key contributors to the health

problems triggered years after exposure.

The war was unique in the levels of physical and emo-

tional stresses created for those who served, as well as for

their families. A significant portion of troops were from the

reserves, rather than active enlistees. Deployment occurred

at unprecedented speed. Most troops were given multiple

vaccinations that singularly do not have adverse effects; their

combined effects were not tested before distribution. Detec-

tors often signaled the presence of chemical weapons during

the conflict, but were mostly ignored as inaccurate. The

soldiers worked long hours in extreme temperatures, lived

in crowded and unsanitary conditions where pesticides were

used indiscriminately to rid areas of flies, snakes, spiders,

and scorpions, and breathed and had dermal exposures to

chemicals

from the continuous oil fires—burning trash,

feces, fuels, and solvents. Blazing sun, blowing sand and

biting sandflies further increased the discomfort and stress

of military life in the

desert

. Exposures to the various fumes

often exceeded federal standards and World Health Organi-

684

zation health guidelines; these alone could have caused “per-

manent impairment,” according to a 1994 National Institutes

of Health report.

The U.S. military now admits it was inadequately

prepared for chemical and biological warfare, which it knew

Iraq had previously used. Three of four reserve units, for

example, didn’t have protective gear. The drug pyridostig-

mine bromide (PB, 3-dimethylaminocarbonyloxy-N-meth-

ylpyridium bromide) was given to almost 400,000 troops

before and during the Gulf War to combat the effects of

nerve gas, even though it is approved by the

Food and Drug

Administration

(FDA) only for treatment of the neurologi-

cal disorder myasthenia gravis. The FDA agreed on the

condition that commanders inform troops what they were

taking and what the potential side effects were. One survey,

however, found that 63 of 73 veterans who had taken the

drug did not receive such information. Records were not

kept on who took which drugs or vaccines, as required by

FDA and Defense Department guidelines.

While the Defense Department and other government

agencies have spent more than $80 million to try to identify

the cause of veterans’ ailments, a privately funded team of

toxicologists and epidemiologists may have discovered an

explanation for at least some problems experienced by Gulf

War veterans. Researchers treated chickens in 1996 with

nonlethal doses of three chemicals veterans were exposed to:

DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and chlorpyrifos (O,O-

diethyl O-3,5,6-trichloropyridinyl phosphorothioate), used

topically or sprayed on uniforms as insecticides, and the anti-

nerve gas drug pyridostigmine bromide. They found that

simultaneous exposure to two or more of the insecticides

and drugs damaged the chickens’ nervous system, even

though none of the chemicals caused problems by itself. The

range of symptoms the chickens developed is similar to

those the veterans describe. A similar study by the Defense

Department found that the chemicals were more toxic to

rats when given together than individually. Follow up studies

are underway to determine if this also holds for humans.

The researchers hypothesize that multiple chemicals

overwhelmed the animals’ ability to neutralize them. The

enzyme

butyrylcholinesterase, which circulates in the blood,

breaks down a variety of nitrogen-containing organic com-

pounds, including the three substances tested. But the anti-

nerve gas drug, in particular, can monopolize the enzyme,

preventing it from dealing with the insecticides. Those

chemicals could then sneak into the brain, and cause damage

they would not produce on their own.

Many veterans believe that, while the drugs and pesti-

cides may have played a role in their ailments, so have

chemical weapons. Troops could have been subjected to

much more low-level exposure of chemical weapons than

previously believed, either directly or via air plumes, because

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gulf War syndrome

75% of Iraq’s chemical weapons production capability, along

with 21 chemical weapons storage sites, were destroyed by

allied air raids.

In addition, U.S. battalions blew up an Iraqi arms

dump soon after the war was over, before many troops had

left the Gulf. Khamisiyah, an enormous ammunition storage

site, covered 20 mi

2

(50 km

2

) with 100 ammunition bunkers

and other storage facilities. Two large explosions were set

off, one on March 4 and a second on March 10, 1991.

Smaller demolition operations continued in the area through

most of April 1991.

While the site was not believed to have contained

chemical weapons at the time, the Defense Department

admitted in June 1996 that the complex had included nerve

and mustard gases. The Central Intelligence Agency also

admitted in April 1997 that it knew in 1986 that thousands

of mustard gas weapons had been stored at the Khamisiyah

depot, but the agency failed to include it on a list of suspected

sites provided to the Defense Department before the 1991

war, which led troops to assume it was safe to blow it up.

Weather data shows that upper-level winds in the gulf

were blowing in a southerly direction during and after the

bombing. Thus, vapors carried by these winds could have

contaminated troops hundreds of miles away. A 1974 report,

Delayed Toxic Effects of Chemical Warfare Agents, found that

chemicals weapons plant workers suffer as many chronic

symptoms as those now suffered by Gulf War veterans,

including neurological, gastrointestinal and heart problems,

loss of memory and a greater risk of

cancer

; exposure to

these chemicals may also create birth effects in children. A

1995 study by a British medical researcher found many of

the same symptoms in

Third World

people exposed to

or-

ganophosphate

insecticides, like DEET used in the Gulf

War, which are diluted versions of chemical weapons.

While British, Canadian and Slovak veterans have

reported similar ailments, albeit in smaller numbers, no

French veterans have complained of such illnesses, despite

extensive publicity. This is also providing valuable clues to

the U.S. veterans’ maladies, in several ways. For example,

the French did not use many of the vaccines that the British

and Americans used, including pyridostigmine bromide.

French camps were not sprayed with insecticides as a preven-

tive measure, rather only when needed to control

pest

popu-

lations. When they did spray, they did not use organophos-

phates. Finally, the French were nowhere near the

Khamisiyah munitions depot when the destruction occurred.

In February 1997, a series of study results established

the most definitive links between Gulf War syndrome and

chemicals to date. The research identifies six “syndromes,”

or clusters of like symptoms in discrete groups of veterans,

and associates each with distinct events during the war.

Troops who reported exposure to chemical weapons, for

685

example, are likely to suffer from confusion, balance prob-

lems, impotence and depression. Other sets of symptoms

correspond to the use of insect repellants and anti-nerve gas

drugs. While not conclusive, these findings will likely spur

further research into the effects of low-level exposure to

certain chemicals.

Such research was advocated by the presidential advi-

sory committee, a 12-member panel of veterans, scientists,

and health care and policy experts established in 1995. The

committee held 18 public meetings between August 1995

and November 1996 to investigate the nature of Gulf War

veterans’ illnesses, health effects of Gulf War risk factors,

and the government’s response to Gulf War illnesses. While

the committee’s final report in January 1997 concluded that

no single, clinically recognizable disease can be attributed

to Gulf War service, it recommended additional research

on the long-term health effects of low-level exposures to

chemical weapons, on the synergistic effects of pyridostig-

mine bromide with other Gulf War risk factors, and on the

body’s physical response to stress.

While the debate continues, the Veterans Affairs and

the Defense Departments are providing free medical help

to any veteran who believes he or she is suffering from

Gulf War Syndrome. In January 1997, President Clinton

proposed new regulations that would extend the time avail-

able to veterans to prove their disabilities are related to

Gulf War service from two to 10 years. He also initiated a

presidential review to ensure that in any future deployments

the health of service men and women and their families is

better protected.

Definitive answers as to the causes and treatments for

veterans’ ailments may be years away. What is clear is that

the complex biological, chemical, physical and psychological

stresses of the

Persian Gulf War

appear to have produced

a variety of complex adverse health effects. No single disease

or syndrome is apparent, but rather multiple illnesses with

overlapping symptoms and causes. If what had been consid-

ered acceptable trace levels of chemical agents in the war

environment

are found to be harmful, the U.S. military

will have to revamp the way it protects its forces against

even those tiny amounts. Tragically, that would mean that

not only did “friendly fire” account for nearly 25% of the

146 U.S. deaths, but also that allied actions were responsible

for the war’s most persistent and haunting pain.

[Sally Cole-Misch]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Abou-Donia, M.B., et. al. “Increased Neurotoxicity Following Concurrent

Exposure to Pyridostigmine Bromide, DEET and Chlorpyrifos.” Funda-

mental and Applied Toxicology 34, no. 190 (1996): 201–.222.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gullied land

Gully erosion in Australia. (Photograph by A. B. Joyce. Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

Barry, J., and R. Watson. “Scent of War.” Newsweek, September 30, 1996,

38–39.

Cary, P., and M. Tharp. “The Gulf War’s Grave Aura.” U.S. News &

World Report, 121, no. 2, July 8, 1996, 38–39.

Cowley, G., and M. Hager. “Poisoned in the Gulf?” Newsweek 127, no.

18, April 29, 1996, 74.

———. “A Gulf War Cover-up?” Newsweek, November 11, 1996, 48–49.

“Darkness at Noon.” The Economist 342, no. 7999 (January 1, 1997): 71–74.

National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Workshop Panel.

“The Persian Gulf Experience and Health.” Journal of the American Medial

Association 272, no. 5 (August 3, 1994): 391–395.

Pennisi, E. “Chemicals Behind Gulf War Syndrome.” Science 272, no. 5261

(April 26, 1996): 479–480.

Shenon, P. “CIA Says It Knew of Iraq Chemicals.” Detroit Free Press, April

10, 1997, 1–3A.

Thompson, M. “The Silent Treatment.” Time, 148, no. 28, December 23,

1996, 33–37.

Waldman, A. “Credibility Gulf.” The Washington Monthly, 28, no. 12,

December 1996, 28–35.

Gullied land

Areas where all diagnostic

soil

horizons have been removed

by flowing water, resulting in a network of V-shaped or U-

686

shaped channels. Generally, gullies are so deep that extensive

reshaping is necessary for most uses. They cannot be crossed

with normal farm machinery. While gullied land can occur

on any land, they are often most prevalent on loess, sandy,

or other soils with low cohesion. See also Erosion; Soil profile;

Soil texture

Gymnogyps californianus

see

California condor

Gypsy moth

The gypsy moth (Portheria dispar), a native of Europe and

parts of Asia, has been causing both ecological and economic

damage in the eastern United States and Canada since its

introduction in New England in the 1860s.

In 1869, french entomologist Leopold Trouvelet

brought live specimens of the insect to Medford, Massachu-

setts for experimentation with silk production. Several indi-

vidual specimens escaped and became an established popula-