Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Golf courses

be done particularly effectively in the brushy and forested

areas between the holes and their approaches. The habitat

quality in these less-intensively managed areas can also be

enhanced by providing nesting boxes and brush piles for use

by birds and small mammals, and by other management

practices known to favor

wildlife

. Habitat quality is also

improved by planting native species of plants wherever it is

feasible to do so.

In addition to land appropriation, some of the manage-

ment practices used on golf courses carry the risk of causing

local environmental damage. This is particularly the case of

putting greens, which are intensively managed to maintain

an extremely even and consistent lawn surface.

For example, to maintain a

monoculture

of desired

species of grasses on putting greens and lawns, intensive

management practices must be used. These include frequent

mowing,

fertilizer

application, and the use of a variety of

pesticidal

chemicals

to deal with various pests affecting the

turfgrass. This may involve the application of such herbicides

as Roundup (glyphosate),

2,4-D

, MCPP, or Dicamba to deal

with undesirable weeds.

Herbicide

application is particularly

necessary when putting greens and lawns are being first

established. Afterward their use can be greatly reduced by

only using spot-applications directly onto turf-grass weeds.

Similarly, fungicides might be used to combat infestations

of turf-grass disease

fungi

, such as the fusarium blight (Fu-

sarium culmorum), take-all patch (Gaeumannomyces graminis),

and rhizoctonia blight (Rhizoctonia solani).

Infestations by turf-damaging insects may also be a

problem, which may be dealt with by one or more insecticide

applications. Some important insect pests of golf-course turf-

grasses include the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), chafer

beetles (Cyclocephala spp.), June beetles (Phyllophaga spp.),

and armyworm beetle (Pseudaletia unipuncta). Similarly, ro-

denticides may be needed to get rid of moles (Scalopus aquat-

icus) and their burrows.

Golf courses can also be a major user of water, mostly

for the purposes of

irrigation

in dry climates or during

droughty periods. This can be an important problem in

semi-arid regions, such as much of the southwestern U.S.,

where water is a scare and valuable commodity with many

competing users. To some degree, water use can be decreased

by ensuring that irrigation is only practiced when necessary,

and only in specific places where it is needed, rather than

according to a fixed schedule and in a broadcast manner. In

some climatic areas, nature-scaping and other low-mainte-

nance practices can be used over extensive areas of golf

courses. This can result in intensive irrigation only being

practiced in key areas, such as putting greens, and to a lesser

degree fairways and horticultural lawns.

Many golf courses have ponds and lakes embedded in

their spatial design. If not carefully managed, these

647

waterbodies can become severely polluted by nutrients, pesti-

cides, and eroded materials. However, if care is taken with

golf-course management practices, their ponds and lakes can

sustain healthy ecosystems and provide refuge habitat for

local native plants and animals.

Increasingly, golf-course managers and industry asso-

ciations are attempting to find ways to support their sport

while not causing an unacceptable amount of environmental

damage. One of the most important initiatives of this kind

is the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program for Golf

Courses, run by the Audubon International, a private conser-

vation organization. Since 1991, this program has been pro-

viding

environmental education

and conservation advice

to golf-course managers and designers. By 2002, member-

ship in this Audubon program had grown to more than

2,300 courses in North America and elsewhere in the world.

The Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program for

Golf Courses provides advice to help planners and managers

with: (a) environmental planning; (b) wildlife and habitat

management; (c) chemical use reduction and safety; (d)

water conservation

; and (e) outreach and education about

environmentally appropriate management practices. If a golf

course completes recommended projects in all of the compo-

nents of the program, it receives recognition as a Certified

Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary. This allows the golf course

to claim that it is conducting its affairs in a certifiably “green”

manner. This results in tangible environmental benefits of

various kinds, while being a source of pride of accomplish-

ment for employees and managers, and providing a potential

marketing benefit to a clientele of well-informed consumers.

There are many specific examples of environmental

benefits that have resulted from golf courses engaged in

the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program. For instance,

seven golf courses in Arizona and Washington have allowed

the installation of 150 artificial nesting burrows for bur-

rowing owls (Athene cunicularia), an endangered species, on

suitable habitat on their land. In 2000, Audubon Interna-

tional conducted a survey of cooperating golf courses, and the

results were rather impressive. About 78% of the respondents

reported that they had decreased the total amount of turf-

grass area on their property; 73% had taken steps to increase

the amount of wildlife habitat; 45% were engaged in an

ecosystem restoration project; 90% were attempting to use

native plants in their horticulture; and 85% had decreased

their use of pesticides and 91% had switched to lower-

toxicity chemicals. Just as important, about half of the re-

spondents believed that there had been an improvement in

the playing quality of their golf course and in the satisfaction

of both employees and their client golfers. Moreover, none

of the respondents believed that any of these values had been

degraded as a result of adopting the management practices

advised by the Audubon International program.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Good wood

These are all highly positive indicators. They suggest

that the growing and extremely popular sport of golf can,

within limits, potentially be practiced in ways that do not

cause unacceptable levels of environmental and ecological

damage.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Balogh, J. C., and W. J. Walker, eds. Golf Course Management and Construc-

tion: Environmental Issues. Leeds, UK: Lewis Publishers, 1992.

Gillihan, S. W. Bird Conservation on Golf Courses: A Design and Management

Manual. Ann Arbor, MI: Ann Arbor Press, 1992.

Sachs, P. D., and R.T. Luff. Ecological Golf Course Management. Ann Arbor,

MI: Ann Arbor Press, 2002.

O

THER

“Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program for Golf.” Audubon Interna-

tional. 2002 [cited July 2002]. –http://www.audubonintl.org/programs/acss/

golf.htm>.

United States Golf Association. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.usga.org>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

United States Golf Association, P.O. Box 708, Far Hills, N.J. USA 07931-

0708, Fax: 908-781-1735, Email: usga.org, http://www.usga.org/

Good wood

Good wood, or smart wood, is a term certifying that the

wood is harvested from a forest operating under environmen-

tally sound and sustainable practices. A “certified wood”

label indicates to consumers that the wood they purchase

comes from a forest operating within specific guidelines

designed to ensure future use of the forest. A well-managed

forestry operation takes into account the overall health of the

forest and its ecosystems, the use of the forest by indigenous

people and cultures, and the economic influences the forest

has on local communities. Certification of wood allows the

wood to be traced from harvest through processing to the

final product (i.e., raw wood or an item made from wood)

in an attempt to reduce uncontrollable

deforestation

, while

meeting the demand for wood and wood products by con-

sumers around the world.

Public concern regarding the disappearance of tropical

forests initially spurred efforts to reduce the destruction of

vast acres of rainforests by identifying environmentally re-

sponsible forestry operations and encouraging such practices

by paying foresters higher prices. Certification, however, is

not limited to tropical forests. All forest types—tropical,

temperate, and boreal (those located in northern climes)—

from all countries may apply for certification. Plantations

(stands of timber that have been planted for the purpose of

logging

or that have been altered so that they no longer

648

support the ecosystems of a natural forest) may also apply

for certification.

Certification of forests and forest owners and managers

is not required. Rather, the process is entirely voluntary.

Several organizations currently assess forests and

forest

management

operations to determine whether they meet

the established guidelines of a well-managed, sustainable

forest. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), founded in

1993, is an organization of international members with envi-

ronmental, forestry, and socioeconomic backgrounds that

monitors these organizations and verifies that the certifica-

tion they issue is legitimate.

A set of 10 guiding principles known as Principles and

Criteria (P&C) were established by the FSC for certifying

organizations to utilize when evaluating forest management

operations. The P&C address a wide range of issues, includ-

ing compliance with local, national, and international laws

and treaties; review of the forest operation’s management

plans; the religious or cultural significance of the forest to

the indigenous inhabitants; maintenance of the rights of the

indigenous people to use the land; provision of jobs for

nearby communities; the presence of threatened or

endan-

gered species

; control of excessive

erosion

when building

roads into the forest; reduction of the potential for lost

soil

fertility as a result of harvesting; protection against the

invasion of non-native

species

;

pest

management that limits

the use of certain chemical types and of genetically altered

organisms; and protection of forests when deemed necessary

(for example, a forest that protects a

watershed

or that

contains threatened and/or endangered species).

Guarding against illegal harvesting is a major hurdle

for those forest managers working to operate within the

established regulations for certification. Forest devastation

occurs not only from harvesting timber for wood sales but

when forests are clear cut to make way for cattle crazing or

farming, or to provide a fuel source for local inhabitants.

Illegal harvesting often occurs in developing countries where

enforcement against such activities is limited (for example,

the majority of the trees harvested in Indonesia are done so

illegally).

Critics argue against the worthiness of managing for-

ests, suggesting that the logging of select trees from a forest

should be allowed and that once completed, the remaining

forest should be placed off limits to future logging. Neverthe-

less, certified wood products are in the market place; large

wood and wood product suppliers are offering certified wood

and wood products to their consumers. In 2001 the Forest

Leadership Forum (a group of environmentalists, forest in-

dustry representatives, and retailers) met to identify how

wood retailers can promote sustainable forests. It is hoped

that consumer demand for good wood will drive up the

number of forests participating in the certification program,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Jane Goodall

thereby reducing the rate of irresponsible deforestation of

the world’s forests.

[Monica Anderson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bass, Stephen, et al. Certification’s Impact on Forests, Stakeholders and Supply

Chains. London: IIED, 2001.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Forest Stewardship Council United States, 1155 30th Street, NW, Suite

300, Washington, DC USA 20007 (202) 342 0413, Fax: (202) 342 6589,

Email: info@foreststewardship.org, <http://www.fscus.org<

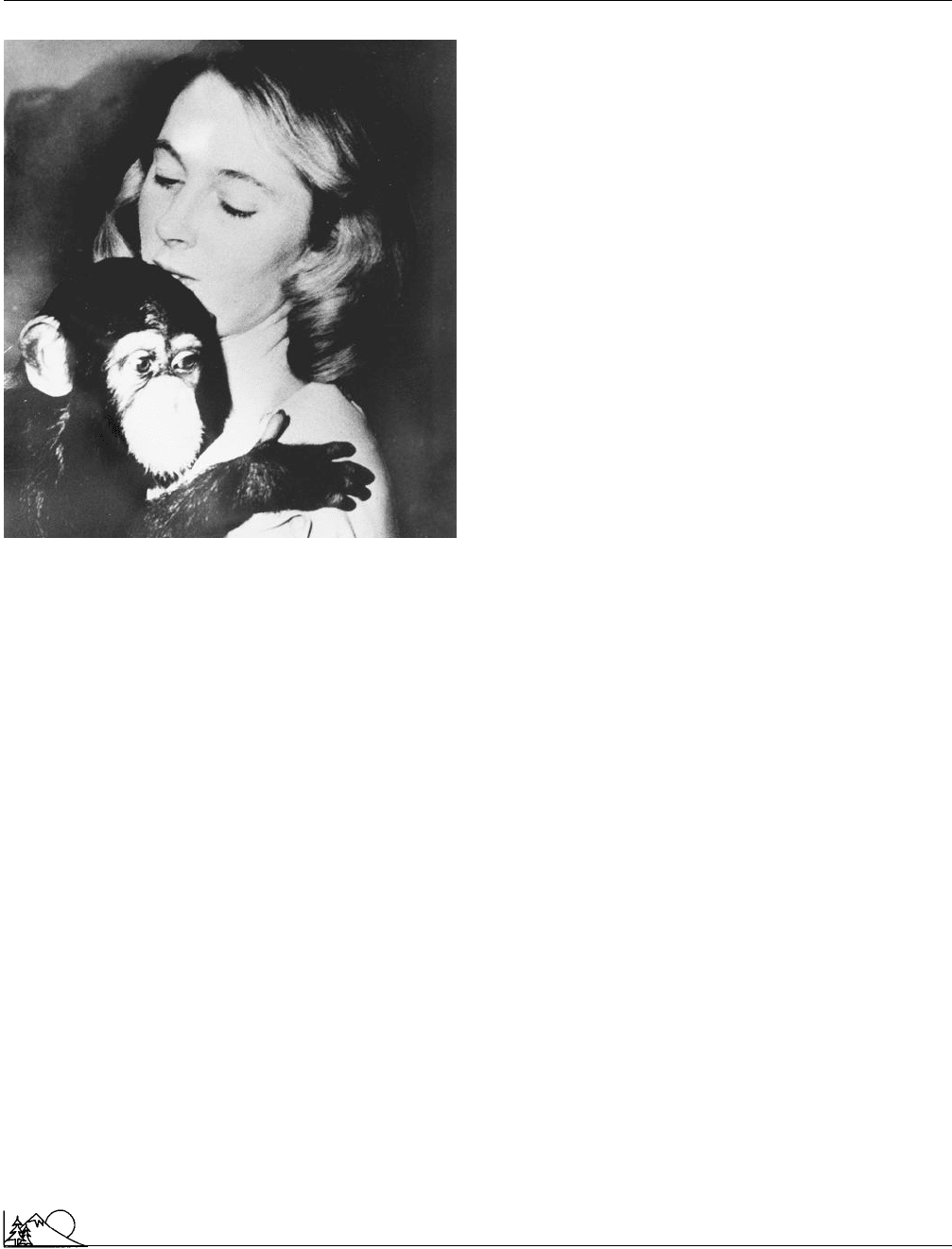

Jane Goodall (1934 – )

English primatologist and ethnologist

Jane Goodall is known worldwide for her studies of the

chimpanzees

of the Gombe Stream Reserve in Tanzania,

Africa. She is well respected within the scientific community

for her ground-breaking field studies and is credited with

the first recorded observation of chimps eating meat and

using and making tools. Because of Goodall’s discoveries,

scientists have been forced to redefine the characteristics

once considered as solely human traits. Goodall is now lead-

ing efforts to ensure that animals are treated humanely both

in their wild habitats and in captivity.

Goodall was born in London, England, on April 3,

1934, to Mortimer Herbert Goodall, a businessperson and

motor-racing enthusiast, and the former Margaret Myfanwe

Joseph, who wrote novels under the name Vanne Morris

Goodall. Along with her sister, Judy, Goodall was reared in

London and Bournemouth, England. Her fascination with

animal behavior began in early childhood. In her leisure

time, she observed native birds and animals, making exten-

sive notes and sketches, and read widely in the literature of

zoology and ethnology. From an early age, she dreamed of

traveling to Africa to observe exotic animals in their natural

habitats.

Goodall attended the Uplands private school, receiving

her school certificate in 1950 and a higher certificate in

1952. At age eighteen she left school and found employment

as a secretary at Oxford University. In her spare time, she

worked at a London-based documentary film company to

finance a long-anticipated trip to Africa. At the invitation

of a childhood friend, she visited South Kinangop, Kenya.

Through other friends, she soon met the famed anthropolo-

gist Louis Leakey, then curator of the Coryndon Museum

in Nairobi. Leakey hired her as a secretary and invited her

to participate in an anthropological dig at the now famous

Olduvai Gorge, a site rich in fossilized prehistoric remains

of early ancestors of humans. In addition, Goodall was sent

649

to study the vervet monkey, which lives on an island in Lake

Victoria.

Leakey believed that a long-term study of the behavior

of higher primates would yield important evolutionary infor-

mation. He had a particular interest in the chimpanzee, the

second most intelligent primate. Few studies of chimpanzees

had been successful; either the size of the safari frightened

the chimps, producing unnatural behaviors, or the observers

spent too little time in the field to gain comprehensive

knowledge. Leakey believed that Goodall had the proper

temperament to endure long-term isolation in the wild. At

his prompting, she agreed to attempt such a study. Many

experts objected to Leakey’s selection of Goodall because

she had no formal scientific education and lacked even a

general college degree.

While Leakey searched for financial support for the

proposed Gombe Reserve project, Goodall returned to En-

gland to work on an animal documentary for Granada Tele-

vision. On July 16, 1960, accompanied by her mother and

an African cook, she returned to Africa and established a

camp on the shore of Lake Tanganyika in the Gombe Stream

Reserve. Her first attempts to observe closely a group of

chimpanzees failed; she could get no nearer than 500 yd

(457 m) before the chimps fled. After finding another suit-

able group of chimpanzees to follow, she established a non-

threatening pattern of observation, appearing at the same

time every morning on the high ground near a feeding area

along the Kakaombe Stream valley. The chimpanzees soon

tolerated her presence and, within a year, allowed her to

move as close as 30 ft (9 m) to their feeding area. After two

years of seeing her every day, they showed no fear and often

came to her in search of bananas.

Goodall used her newfound acceptance to establish

what she termed the “banana club,” a daily systematic feeding

method she used to gain trust and to obtain a more thorough

understanding of everyday chimpanzee behavior. Using this

method, she became closely acquainted with more than half

of the reserve’s one hundred or more chimpanzees. She

imitated their behaviors, spent time in the trees, and ate

their foods. By remaining in almost constant contact with the

chimps, she discovered a number of previously unobserved

behaviors. She noted that chimps have a complex social

system, complete with ritualized behaviors and primitive but

discernible communication methods, including a primitive

“language” system containing more than twenty individual

sounds. She is credited with making the first recorded obser-

vations of chimpanzees eating meat and using and making

tools. Tool making was previously thought to be an exclu-

sively human trait, used, until her discovery, to distinguish

man from animal. She also noted that chimpanzees throw

stones as weapons, use touch and embraces to comfort one

another, and develop long-term familial bonds. The male

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Jane Goodall

plays no active role in family life but is part of the group’s

social

stratification

. The chimpanzee “caste” system places

the dominant males at the top. The lower castes often act

obsequiously in their presence, trying to ingratiate them-

selves to avoid possible harm. The male’s rank is often related

to the intensity of his entrance performance at feedings and

other gatherings.

Ethologists had long believed that chimps were exclu-

sively vegetarian. Goodall witnessed chimps stalking, killing,

and eating large insects, birds, and some bigger animals,

including baby baboons and bushbacks (small antelopes). On

one occasion, she recorded acts of cannibalism. In another

instance, she observed chimps inserting blades of grass or

leaves into termite hills to lure worker or soldier termites

onto the blade. Sometimes, in true toolmaker fashion, they

modified the grass to achieve a better fit. Then they used

the grass as a long-handled spoon to eat the termites.

In 1962 Baron Hugo van Lawick, a Dutch

wildlife

photographer, was sent to Africa by the National Geographic

Society to film Goodall at work. The assignment ran longer

than anticipated; Goodall and van Lawick were married on

March 28, 1964. Their European honeymoon marked one

of the rare occasions on which Goodall was absent from

Gombe Stream. Her other trips abroad were necessary to

fulfill residency requirements at Cambridge University,

where she received a Ph.D. in ethnology in 1965, becoming

only the eighth person in the university’s long history who

was allowed to pursue a Ph.D. without first earning a bacca-

laureate degree. Her doctoral thesis, “Behavior of the Free-

Ranging Chimpanzee,” detailed her first five years of study

at the Gombe Reserve.

Van Lawick’s film, Miss Goodall and the Wild Chim-

panzees, was first broadcast on American television on De-

cember 22, 1965. The film introduced the shy, attractive,

unimposing yet determined Goodall to a wide audience.

Goodall, van Lawick (along with their son, Hugo, born in

1967), and the chimpanzees soon became a staple of Ameri-

can and British public television. Through these programs,

Goodall challenged scientists to redefine the long-held “dif-

ferences” between humans and other primates.

Goodall’s fieldwork led to the publication of numerous

articles and five major books. She was known and respected

first in scientific circles and, through the media, became a

minor celebrity. In the Shadow of Man, her first major text,

appeared in 1971. The book, essentially a field study of

chimpanzees, effectively bridged the gap between scientific

treatise and popular entertainment. Her vivid prose brought

the chimps to life, although her tendency to attribute human

behaviors and names to chimpanzees struck some critics

being as manipulative. Her writings reveal an animal world

of social drama, comedy, and tragedy where distinct and

varied personalities interact and sometimes clash.

650

From 1970 to 1975 Goodall held a visiting professor-

ship in psychiatry at Stanford University. In 1973 she was

appointed honorary visiting professor of Zoology at the Uni-

versity of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, a position she still

holds. Her marriage to van Lawick over, she wed Derek

Bryceson, a former member of Parliament, in 1973. He has

since died. Until recently, Goodall’s life has revolved around

Gombe Stream. But after attending a 1986 conference in

Chicago that focused on the ethical treatment of chimpan-

zees, she began directing her energies more toward educating

the public about the wild chimpanzee’s endangered

habitat

and about the unethical treatment of chimpanzees that are

used for scientific research.

To preserve the wild chimpanzee’s

environment

,

Goodall encourages African nations to develop nature-

friendly tourism programs, a measure that makes wildlife

into a profitable resource. She actively works with business

and local governments to promote ecological responsibility.

Her efforts on behalf of captive chimpanzees have taken her

around the world on a number of lecture tours. She outlined

her position strongly in her 1990 book Through a Window:

“The more we learn of the true nature of non-human ani-

mals, especially those with complex brains and corresponding

complex social behaviour, the more ethical concerns are

raised regarding their use in the service of man-whether this

be in entertainment, as ’pets,’ for food, in research labora-

tories or any of the other uses to which we subject them.

This concern is sharpened when the usage in question leads

to intense physical or mental suffering-as is so often true

with regard to vivisection.”

Goodall’s stance is that scientists must try harder to

find alternatives to the use of animals in research. She has

openly declared her opposition to militant

animal rights

groups who engage in violent or destructive demonstrations.

Extremists on both sides of the issue, she believes, polarize

thinking and make constructive dialogue nearly impossible.

While she is reluctantly resigned to the continuation of

animal research, she feels that young scientists must be edu-

cated to treat animals more compassionately. “By and large,”

she has written, “students are taught that it is ethically ac-

ceptable to perpetrate, in the name of science, what, from

the point of view of animals, would certainly qualify as

torture.”

Goodall’s efforts to educate people about the ethical

treatment of animals extends to young children as well.

Her 1989 book, The Chimpanzee Family Book, was written

specifically for children, to convey a new, more humane

view of wildlife. The book received the 1989 Unicef/Unesco

Children’s Book-of-the-Year award, and Goodall used the

prize money to have the text translated into Swahili. It has

been distributed throughout Tanzania, Uganda, and Bu-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Albert Gore Jr.

Jane Goodall. (The Library of Congress.)

rundi to educate children who live in or near areas populated

by chimpanzees. A French version has also been distributed

in Burundi and Congo.

In recognition of her achievements, Goodall has re-

ceived numerous honors and awards, including the Gold

Medal of

Conservation

from the San Diego Zoological

Society in 1974, the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation

Prize in 1984, the Schweitzer Medal of the

Animal Welfare

Institute

in 1987, the National Geographic Society Centen-

nial Award in 1988, and the Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences

in 1990. In 1995, Goodall was presented with a CBE (Com-

mander of the British Empire) from Queen Elizabeth II.

Many of Goodall’s endeavors are conducted under the aus-

pices of the Jane Goodall Institute for Wildlife Research,

Education, and Conservation, a nonprofit organization lo-

cated in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In April of 2002, it was

revealed that Goodall was chosen to be a United Nations

Messenger of Peace.

[Tom Crawford]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Green, T. The Restless Spirit: Profiles in Adventure. Walker, 1970.

Goodall, J. Jane Goodall’s Animal World: Chimpanzees. Macmillan, 1989.

651

———. Through a Window: My Thirty Years with the Chimpanzees of Gombe.

Houghton, 1990.

Montgomery, S.Walking with the Great Apes: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey,

Birute Galdikas. Houghton Mifflin, 1991.

Smith, W. “The Wildlife of Jane Goodall.” USAir, February 1991, 42–47.

Gopherus agassizii

see

Desert tortoise

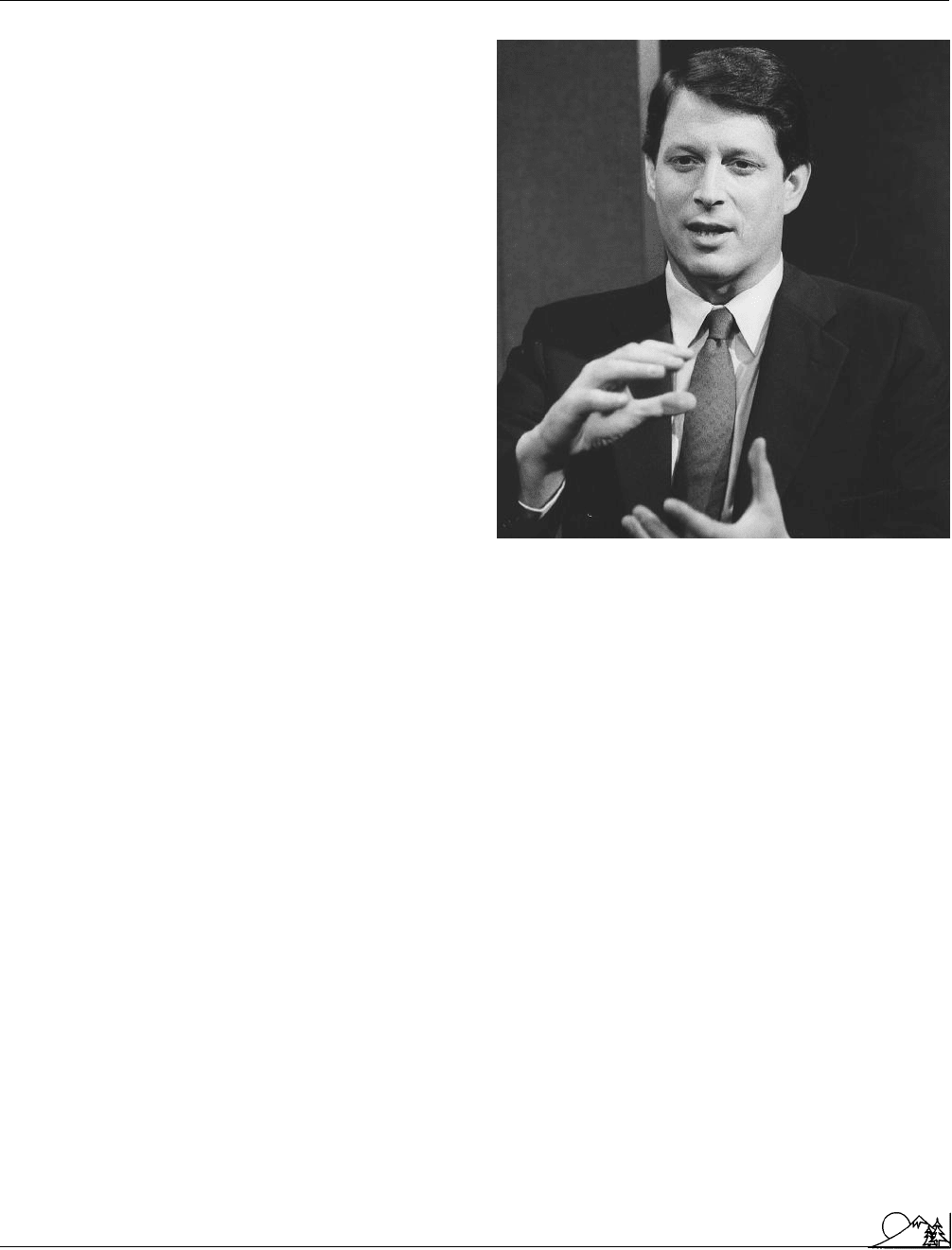

Albert Gore Jr. (1948 – )

American former U.S. representative, senator and vice

president of the United States

Albert Gore, Jr. was born and raised in Washington, D.C.,

where his father was a well-known and widely respected

representative and later senator from Tennessee. Gore at-

tended St. Alban’s Episcopal School for Boys, where he

excelled both academically and athletically. He later went

to Harvard, earning a bachelor’s degree in government. After

graduation he enlisted in the army, serving as a reporter in

Vietnam in a war he was opposed to. After completing his

tour of duty, in 1974 Gore entered the law school at Vander-

bilt University. Following in his father’s footsteps, Gore

ran for Congress, was elected, and served five terms before

running for and winning a Senate seat in 1984. He served in

the Senate until 1992, when then-governor and Democratic

presidential candidate Bill Clinton selected him as his vice

presidential running-mate. After winning the 1992 election

Vice President Gore became the Clinton administration’s

chief environmental advisor. He was also largely responsible

for President Clinton’s selection of

Carol Browner

as head

of the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and Bruce

Babbit as Secretary of the Interior.

A self-described “raging moderate,” Gore for more

than two decades championed environmental causes and

drafted and sponsored environmental legislation in the Sen-

ate. He was one of two U.S. senators to attend and take an

active part in the 1992 U.N.-sponsored Rio Summit on the

environment

, and after he became vice president in 1993,

he took a leading role in shaping the Clinton administration’s

environmental agenda. As vice president, Gore’s ability to

shape that agenda was perhaps somewhat limited. At the

close of Clinton’s first term, most environmental organiza-

tions rated his administration’s record on environmental

matters as mixed, at best. Yet clearly environmental groups

had more access to the White House than they had ever

had before. And in his second term, Gore was thought to

be responsible for salvaging the 1997 Kyoto agreement on

climate

change when he flew to Japan as negotiations were

falling apart and personally represented a new American

position.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Albert Gore Jr.

Gore’s most notable contribution to the environmental

movement might be as an author. With a wealth of statistical

and scientific evidence, Gore’s 1992 book Earth in the Bal-

ance makes the case that careless development and growth

have damaged the natural environment; but better policies

and regulations will supply incentives for more environmen-

tally responsible actions by individuals and corporations. For

example, a so-called

carbon tax

could provide financial

incentives for developing new, nonpolluting energy sources

such as solar and wind power. Corporations could also be

given tax credits for using these new sources. By structuring

a system of incentives that favors the protection and restora-

tion of the natural environment, government at the local,

national, and (through the United Nations) international

levels can restore the balance between satisfying human

needs and protecting the earth’s environment. But restoring

this balance, Gore maintained in his book, requires more

than public policy and legislation; it requires changes in basic

beliefs and attitudes toward

nature

and all living creatures.

More specifically, environmental protection and restoration

requires a willingness on the part of individuals to accept

responsibility for their actions (or inaction). At the individual

level, environmental protection means living, working,

eating, and recreating responsibly, with an eye to one’s effects

on the natural and social environment, now and in the future

in which our children and their children will survive.

Despite the strong stances Gore articulated in Earth

in the Balance, his achievements as vice president under

Clinton were more moderate. His former staffer Carol

Browner headed the EPA, and she prevailed in promoting

several major pieces of environmental legislation. But she

had to withstand concerted attacks on her and her office by

the Republican majority in the House and Senate after 1994.

Gore had managed to save the Kyoto treaty on climate

change by his personal efforts in 1997, but the Clinton

administration never committed to specific actions to cut

carbon-dioxide emissions. In August 1998 Gore met with

the leaders of several environmental groups and explained

to them that he had no political backing for advocating

controversial actions like limiting

pollution

from coal-burn-

ing

power plants

. When he ran for president in 2000, the

environment was not a strong feature in his campaign,

though this was an area where he had sharp differences with

his opponent, George W. Bush. In the last months of the

campaign, Gore found himself defending his record on the

environment against Green Party candidate

Ralph Nader

.

Though Gore had the backing of the

Sierra Club

and other

major environmental groups, Nader accused Gore of “eight

years of principles betrayed and promises broken.” In the

end Gore lost the election to Bush, who quickly reversed

Clinton administration environmental policies such as new

652

Albert Gore, Jr. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

standards on drinking water safety, and refused to endorse

the Kyoto climate change treaty.

After losing the election, Gore began lecturing at Fisk

University in Nashville, at UCLA, and at the School of

Journalism at Columbia University. Out of office, he re-

mained for the most part out of the public eye. But he did

speak at Vanderbilt University on

Earth Day

in 2002,

roundly criticizing George W. Bush for his

environmental

policy

. Gore noted that some of his more extreme environ-

mental stances, such as calling for new technology to replace

the internal

combustion

engine, were now being considered

even by Republican lawmakers. In mid-2002, Gore would

not commit to another run for the presidency. But it did

seem that he stood by his earlier ideas, and would continue

to identify himself with the environmental movement.

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gore Jr., Albert. Earth in the Balance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

P

ERIODICALS

Barro, Robert J. “Gore’s ’Reckless and Offensive’ Passion for the Environ-

ment.” Business Week, November 6, 2000, 32.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gorillas

Berke, Richard L. “Lieberman Has One Eye on ’04 Run, the Other, Quite

Expectably, on Gore.” New York Times, May 2, 2002, A25.

Branegan, Jay, and Dick Thompson. “Is Al Gore a Hero or a Traitor?”

Time , April 26, 1999, 66.

“How Green Is Al Gore?” Economist (April 22, 2000): 30.

Jehl, Douglas. “On a Favorite Issue, Gore Finds Himself on a 2-Front

Defense.” New York Times, November 3, 2000, A28.

Seelye, Katherine Q. “Gore, on Earth Day, Says Bush Policies Help Pollut-

ers.” New York Times, April 23, 2002, A16.

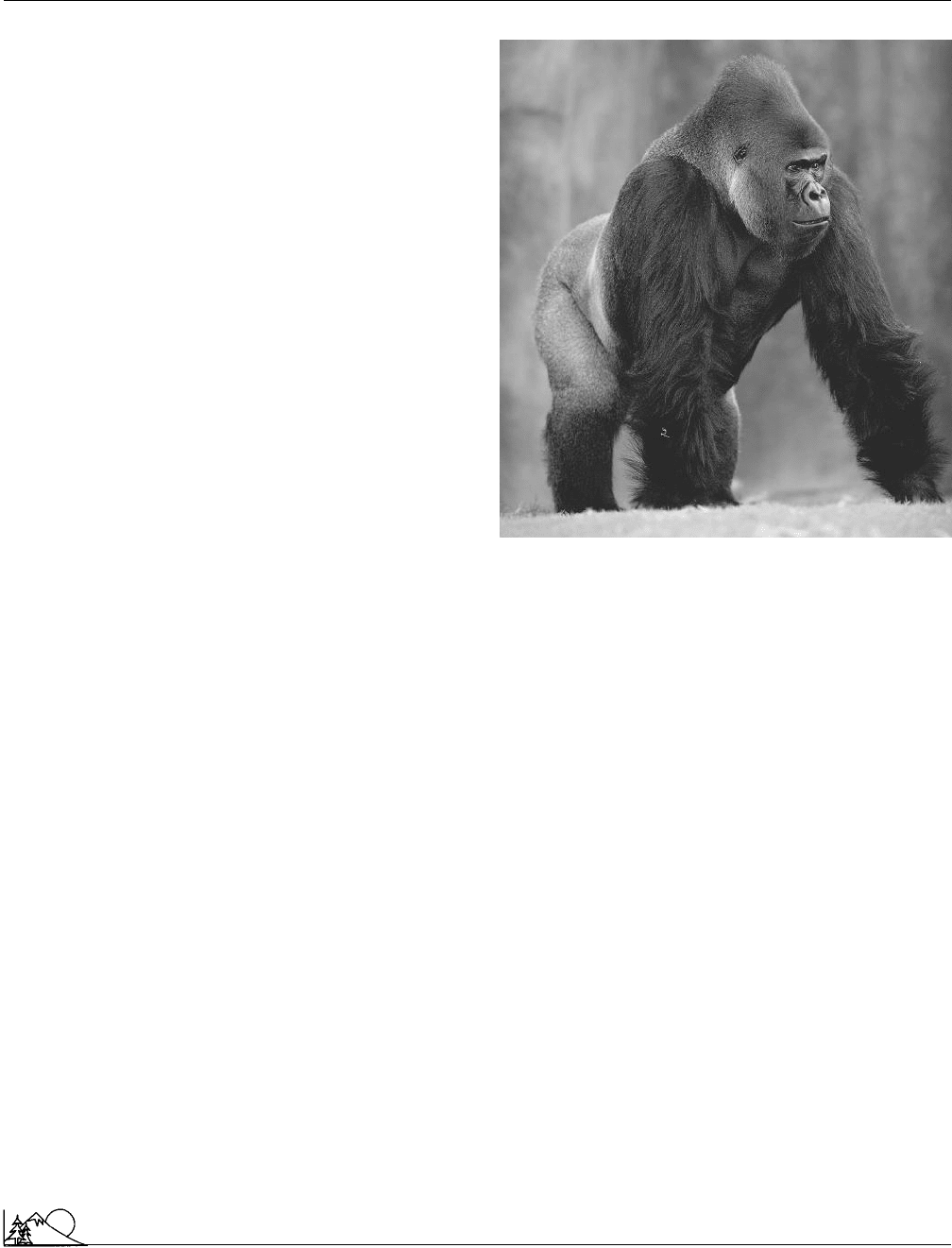

Gorillas

Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) inhabit the forests of Central Africa

and are the largest and most powerful of all primates. Adult

males stand 6 ft (1.8 m) upright (an unnatural position for

a gorilla) and weigh up to 450 lb (200 kg), while females

are much smaller. Gorillas live to about 44 years and mature

males (those usually over 13 years), or silverbacks, are marked

by a band of silver-gray hair on their backs.

Gorillas live in small family groups of several females

and their young, led by a dominant silverback male. The

females comprise a harem for the silverback, who holds the

sole mating rights in the troop. Like humans, female gorillas

produce one infant after a gestation period of nine months.

The large size and great strength of the silverback are advan-

tages in competing with other males for leadership of the

group and in defending the group against outside threats.

During the day these ground-living apes move slowly

through the forest, selecting

species

of leaves, fruit, and

stems from the surrounding vegetation. Their home range

is about 9–14 mi

2

(25–40 km

2

). At night the family group

sleeps in trees, resting on platform nests that they make

from branches; silverbacks usually sleep at the foot of the tree.

Gorillas belong to the family Pongidae (which includes

chimpanzees

Pan], orangutans [Pongo pygmaeus], and

gib-

bons

[genus Hylobates). Together with chimpanzees, gorillas

are the animal species most closely related to man. Like

most megavertebrates, gorilla numbers are declining rapidly

and only about 40,000 remain in the wild. There are three

subspecies, the western lowland gorilla (G. g. gorilla), the

eastern lowland gorilla (G. g. graueri), and the mountain

gorilla (G. g. beringei). The rusty-gray western lowland goril-

las are found in Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea,

Gabon, Congo, Angola, Central African Republic, and Zaire

(now Democratic Republic of the Congo [DRC]). The

black-haired eastern lowland gorillas are found in eastern

DRC.

Deforestation

and

hunting

now threaten lowland

gorillas throughout their range.

The mountain gorilla has been intensely studied in the

field, notably by George Schaller and Dian Fossey, upon

whose life the film Gorillas in the Mist is based. This endan-

gered subspecies is found in the misty mountains of eastern

653

A silverback male gorilla. (Photograph by Jerry L.

Ferrara. Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

Zaire, Rwanda, and Uganda at altitudes of up to 9,000 ft

(3,000 m) and in the Impenetrable Forest in southwest

Uganda. Field research has shown these powerful primates to

be intelligent, peaceful and shy,and of little danger to humans.

Other than humans, gorillas have no real predators,

although leopards will occasionally take young apes. Hunt-

ing,

poaching

(a mountain gorilla is worth $150,000), and

habitat

loss are causing gorilla populations to decline. The

shrinking forest refuge of these great apes is being progres-

sively felled in order to accommodate the ever-expanding

human population. Mountain gorillas are somewhat safe-

guarded in the Virunga Volcanoes

National Park

in

Rwanda. Their protection is funded by strictly controlled

small-group gorilla-viewing tourist experiences that exist

alongside long-term field research programs. Recent popula-

tion estimates are 10,000–35,000 (with 550 in captivity)

western lowland gorillas, 4,000 (with 24 in captivity) eastern

lowlands gorillas, and 620 mountain gorillas.

[Neil Cumberlidge Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Fossey, D. Gorillas in the Mist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Schaller, G. B. The Mountain Gorilla: Ecology and Behavior. Chicago: Uni-

versity of Chicago Press, 1988.

———. The Year of the Gorilla. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

O

THER

The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. [cited May 2002]. <http://

www.gorillafund.org/000_core_frmset.html>.

Gorilla Aid. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.gorillaaid.org>.

Grand Canyon

see

Colorado River; Glen Canyon Dam

Grand Staircase-Escalante National

Monument

The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, en-

compassing 1.7 million acres (700,000 ha) of public lands

on the Colorado Plateau in south-central Utah, was created

on September 18, 1996, by presidential proclamation under

authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906 (34 Stat. 225, 16

U.S.C. 431). The

U.S. Department of the Interior

had

first recommended the creation of the Escalante National

Monument along the Colorado and Green Rivers in 1936.

In 1937, Capitol Reef National Monument was established

in the area northeast of the Escalante Canyons along the

upper portion of Waterpocket Fold. In 1941, the

National

Park Service

studied the basin in conjunction with a com-

prehensive study of

water resources

in the

Colorado River

Basin. The study, published in 1946, identified the Aquarius

Plateau/Escalante River Basin as “a little known, but poten-

tially important

recreation

area.” The area was recognized

as a strategic link between the national parks in southwestern

Utah and the canyon country of southeastern Utah.

A national monument is the designation given to a

particular area to protect “historic landmarks, historic and

prehistoric structures, and objects of historic or scientific

interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled

by the government of the United States.” President

Theo-

dore Roosevelt

exercised this authority to ensure protection

for the Grand Canyon. More than 100 national monuments

have been established by Presidents over the past 90 years,

including Zion, Bryce Canyon, Glacier Bay, Death Valley,

and Grand Teton. The Grand Staircase-Escalante National

Monument was dedicated from the Grand Canyon

National

Park

in Arizona, and no elected official from Utah was at

the ceremony because of the controversy in Utah about the

monuments designation.

The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

was created to preserve geological, paleontological, archaeo-

logical, biological, and historical features of the area. Geolog-

ical features include clearly exposed stratigraphy and struc-

tures. The sedimentary rock layers are relatively undeformed

654

and unobscured by vegetation, providing a view to under-

standing of the processes of the formation of the earth. A

wide variety of geological formations in colors such as red,

pink, orange, and purple have been exposed by millennia of

erosion

. The monument contains significant portions of a

vast geological stairway, which was named the Grand Stair-

case by the geologist Clarence Dutton. This stairway rises

5,500 ft (1,678 m) to the rim of Bryce Canyon in an unbroken

sequence of cliffs and plateaus. The monument also includes

the canyon country of the upper Paria Canyon system, major

components of the White and Vermillion Cliffs and associ-

ated benches, and the Kaiparowits Plateau. The Kaiparowits

Plateau includes about 1,600 mi

2

(2, 574 km

2

) of sedimentary

rock and consists of south-to-north ascending plateaus or

benches, deeply cut by steep-walled canyons. Naturally burn-

ing underground

coal

seams have changed the tops of the

Burning Hills to brick-red. A major landmark, the East

Kaibab Monocline, or Cockscomb, is aligned with the Paun-

saugant, Sevier, and

Hurricane

Faults, which may indicate

that it may also be a fault at depth. The Circle Cliffs, which

features intensively colored red, orange, and purple mounds

and ledges at the base of the Wingate Sandstone Cliffs,

are one of the most distinctive landscapes of the Colorado

Plateau. Inclusion of part of the Waterpocket Fold completes

the protection of this geologic feature, which was begun

with the establishment of the Capitol Reef National Monu-

ment in 1936. There are many arches and natural bridges

within the monument boundaries, including the 130-ft

(39.4-m) high Escalante Natural Bridge, with a 100-ft (30.3-

m) span and the Grosvenor Arch, a double arch. The upper

Escalante Canyons, in the northeastern part of the monu-

ment, include several major arches and bridges and geological

features in narrow, serpentine canyons, where erosion has

exposed sandstone and shale deposits in colors of red, ma-

roon, brown, tan, gray, and white.

Paleontological features include petrified wood, such

as large unbroken logs more than 30 ft (9 m) in length. The

stratigraphy of the Kaiparowits Plateau provides one of the

best and most continuous records of the paleontology of the

late Cretaceous Era. Fossils of marine and

brackish

water

mollusks, turtles,

crocodiles

, lizards, dinosaurs, fishes, and

mammals (including a marsupial primitive mammal) have

been recovered from the Dakota, Tropic Shale, and Wah-

weap Formations and the Tibbett Canyon, Smoky Hollow,

and John Henry members of the Straight Cliffs Formation.

Archeological inventories show extensive use of places

within the monument by Native American cultures. Rec-

orded sites include rock art panels, occupation sites, rock

shelters, campsites, and granaries.

Historical evidence indicates that the monument was

occupied by both Kayenta and Fremont agricultural cultures

for a period of several hundred years centered around

A.D.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Grasslands

1100. The area has been used by modern tribal groups,

including the Southern Paiute and the Navajo. In 1872, an

expedition of John Wesley Powell did initial mapping and

scientific field work in the area. The expedition discovered

the Escalante River, naming it in honor of the Friar Silvester

Valez de Escalante expedition of 1776. The Escalante River

Canyons have been a major barrier to east-west travel in the

region in historic times. The river is presently bridged only

at its upper end. Early Mormon pioneers left many historic

objects, including trails, inscriptions, ghost towns such as

the Old Paria townsite (built in 1874 and abandoned in

1890), rock houses, cowboy camps, and they built the Hole-

in-the Rock Trail in 1879–1880 as part of their colonization

activities. Sixty miles (96.6 km) of the Hole-in-the-Rock

Trail are within the monument, as well as Dance Hall Rock,

used by Mormon pioneers for meetings and dances, and

now a National Historic Site.

As a biological resource, the Grand Staircase-Esca-

lante National Monument spans five life zones, from low-

lying

desert

to

coniferous forest

. Remoteness, limited

travel corridors, and low visitation have helped to preserve

the ecological features, such as areas of relict vegetation,

many of which have existed since the Pleistocene. Pinon-

juniper communities containing trees up to 1,400 years old

and relict sagebrush-grass park vegetation can be found on

No Man’s Mesa, Little No Man’s Mesa, and Four Mile

Bench Old Tree Area. These relict areas can be used to

establish a baseline against which to measure changes in

community dynamics and biogeochemical cycles in areas

impacted by human activity. The monument contains an

abundance of unique isolated communities such as hanging

gardens and canyon bottom communities, with riparian

plants and their pollinators; tinajas, which contain tadpoles,

fairy and clam shrimp, amphibians, and snails; saline seeps,

with plants and animals adapted to highly saline conditions;

dunal pockets, with

species

adapted to shifting sands; rock

crevice communities, consisting of slow-growing species that

can thrive in extremely infertile sites; and cryptobiotic crusts,

which stabilize the highly

erodible

desert soils and provide

nutrients for plants. The

wildlife

of the monument is char-

acterized by a diversity of species, where both northern and

southern

habitat

species intermingle. Mountain lions, bears,

and desert bighorn sheep, as well as over 200 species of

birds, including bald eagles and peregrine falcons, can be

found within the monument. The wildlife concentrates

around the Paria and Escalante Rivers and other riparian

areas.

The Secretary of the Interior, through the

Bureau of

Land Management

(BLM), which in the past has been

responsible for the public lands included within the monu-

ment area, will manage the monument. This is the first

national monument that will be managed by the BLM. The

655

BLM will develop a management plan to address measures

necessary to protect the scientific and historic features within

the monument by three years after the date of establishment

of the monument. The BLM will consult with state and

local governments, other federal agencies, and tribal govern-

ments to prepare the

land use

plan.

The boundaries of the Grand Staircase-Escalante Na-

tional Monument were drawn to exclude as much private

land as possible, as well as the towns of Escalante, Boulder,

Kanab, and Tropic. The national monument designation

applies only to Federal land and not to the approximately

9,000 acres (3,644 ha) of private land remaining within the

boundaries of the monument. Private landowners continue

to have existing rights of access to their property. The land-

owners may participate in land exchanges with the BLM to

trade land within the monument for land of equal value

outside the area. The State of Utah owns about 180,000

acres (73,800 ha) of isolated, 640-acre (262 ha) sections of

school lands within the boundaries of monument. The State

will be allowed to exchange these isolated school lands for

federal lands of equal value outside the monument bound-

aries. All federal lands were withdrawn from sale or leasing

under the

public land

laws upon designation as a national

monument. The designation also prohibited the issuance of

any new mineral leases in the area, including new claims

made under the Mining Law of 1872. Existing uses under

federal or state laws, such as

hunting

, camping, travel, hik-

ing, backpacking, and other recreational activities, as well

as grazing permits, continue under current policies and rules.

The proclamation did not reserve water or make any federal

water rights

claims. As part of the management plan, the

BLM will evaluate the extent to which water is necessary

for the care and management of objects of the monument

and the extent to which further action may be necessary

under federal or state law to ensure availability of water.

[Judith Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bureau of Land Management. List of Historic and Scientific Objects of Interest:

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Salt Lake City: Bureau of

Land Management, 1997.

———. Questions and Answers on the Grand Staircase-Escalante National

Monument. Salt Lake City: Bureau of Land Management, 1997.

Clinton, W. J. Establishment of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monu-

ment: A Proclamation. Washington, DC: The White House, 1996.

Grasslands

Grasslands are environments in which herbaceous

species

,

especially grasses, make up the dominant vegetation. Natural

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Grazing on public lands

grasslands, commonly called

prairie

, pampas, shrub steppe,

palouse, and many other regional names, occur in regions

where rainfall is sufficient for grasses and forbs but too sparse

or too seasonal to support tree growth. Such conditions occur

at both temperate and tropical latitudes around the world.

In addition, thousands of years of human activity—clearing

pastures and fields, burning, or harvesting trees for materials

or fuel—have extended and maintained large expanses of

the world’s grasslands beyond the natural limits dictated by

climate

. Precipitation in temperate grasslands (those lying

between about 25 and 65 degrees latitude) usually ranges

from approximately 10–30 in (25–75 cm) per year. At tropi-

cal and subtropical latitudes, annual grassland precipitation

is generally between 24 and 59 in (60 and 150 cm). Besides

its relatively low volume, precipitation on natural grasslands

is usually seasonal and often unreliable. Grasslands in

mon-

soon

regions of Asia can receive 90% of their annual rainfall

in a few weeks; the remainder of the year is dry. North

American prairies receive most of their moisture in spring,

from snow melt and early rains that are followed by dry,

intensely hot summer months. Frequently windy conditions

further evaporate available moisture.

Grasses (family Gramineae) can make up 90% of grass-

land

biomass

. Long-lived root masses of perennial bunch

grasses and sod-forming grasses can both endure

drought

and allow asexual reproduction when conditions make repro-

duction by seed difficult. These characteristics make grasses

especially well suited to the dry and variable conditions typi-

cal of grasslands. However, a wide variety of grass-like plants

(especially sedges, Cyperaceae) and leafy, flowering forbs

contribute to species richness in grassland

flora

. Small

shrubs are also scattered in most grasslands, and

fungi

,

mosses, and

lichens

are common in and near the

soil

. The

height of grasses and forbs varies greatly, with grasses of

more humid regions standing 7 ft (2 m) or more, while

arid

land grasses may be less than one-half meter tall. Wetter

grasslands may also contain scattered trees, especially in low

spots or along stream channels. As a rule, however, trees do

not thrive in grasslands because the soil is moist only at

intervals and only near the surface. Deeper tree roots have

little access to water, unless they grow deep enough to reach

groundwater

.

Like the plant community, grassland animal commu-

nities are very diverse. Most visible are large herbivores—

from American

bison

and elk to Asian camels and horses

to African kudus and wildebeests. Carnivores, especially

wolves

, large cats, and bears, historically preyed on herds

of these herbivores. Because these carnivores also threatened

domestic herbivores that accompany people onto grasslands,

they have been hunted, trapped, and poisoned. Now most

wolves, bears, and large cats have disappeared from the

world’s grasslands. Smaller species compose the great wealth

656

of grassland

fauna

. A rich variety of birds breed in and

around ponds and streams. Rodents perform essential roles

in spreading seeds and turning over soil. Reptiles, amphibi-

ans, insects, snails, worms, and many other less visible ani-

mals occupy important niches in grassland ecosystems.

Grassland soils develop over centuries or millennia

along with regional vegetation and according to local climate

conditions. Tropical grassland soils, like tropical forest soils,

are highly leached by heavy rainfall and have moderate to

poor

nutrient

and contents. In temperate grasslands, how-

ever, generally light precipitation lets nutrients accumulate

in thick, organic upper layers of the soil. Lacking the acidic

leaf or pine needle litter of forests, these soils tend to be

basic and fertile. Such conditions historically supported the

rich growth of grasses on which grassland herbivores fed.

They can likewise support rich grazing and crop lands for

agricultural communities. Either through crops or domestic

herbivores, humans have long relied on grasslands and their

fertile, loamy soils for the majority of their food.

Along a moisture gradient, the margins of grasslands

gradually merge with moister savannas and woodlands or

with drier,

desert

conditions. As grasslands reach into

higher latitudes or altitudes and the climate becomes to cold

for grasses to flourish, grasslands grade into

tundra

, which

is dominated by mosses, sedges, willows, and other cold-

tolerant plants.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Coupland, R. T., ed. Grassland Ecosystems of the World: Analysis of Grasslands

and Their Uses. London: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Cushman, R. C., and S. R. Jones. The Shortgrass Prairie. Boulder: Pruett

Publishing Co., 1988.

Grazing on public lands

Grazing on public lands is the practice of raising livestock

on land that is not privately owned. Livestock such as cattle

and sheep eat forage (grass and other herbage) on the

public

land

. Through the twentieth century and into the twenty-

first, ranchers grazed livestock on federal and state public

land in the western states.

The western livestock industry developed during the

decades after the Civil War, according to a

Bureau of Land

Management

(BLM) report. People headed west where

the land was open. A prospective rancher just needed a

headquarters, some horses and cowboy employees. Some

ranches consisted of a dugout shelter for the people and a

horse corral.