Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

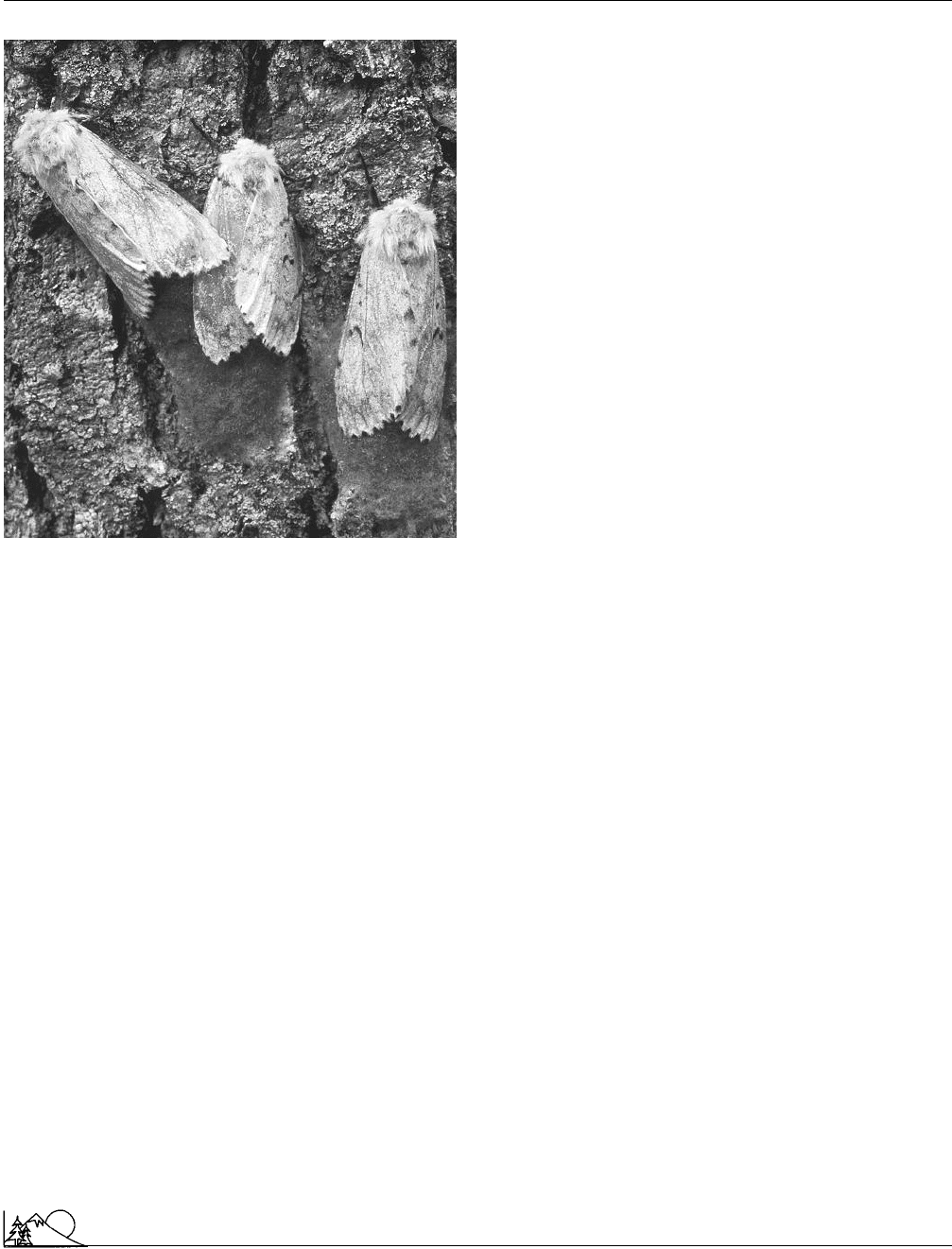

Gypsy moth

Gypsy moth females laying eggs. (Photograph by

Michael Gadumski. Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced

by permission.)

tion over the next 20 years. The destructive abilities of the

gypsy moth became readily apparent to area residents, who

watched large sections of forest be destroyed by the larvae.

From the initial infestation in Massachusetts, the gypsy moth

spread throughout the northeastern United States and south-

eastern Canada. As of 2001, the following states were quar-

antined: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Michigan, New

Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode

Island, and Vermont. More that two-thirds of Virginia is

quarantined, as well as sections of Ohio, Indiana, Maine,

North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. The U. S. De-

partment of Agriculture reports that virtually all areas that

have experienced an invasion of gypsy moths continue to

have extremely high levels of infestation.

Gypsy moths have a voracious appetite for leaves, and

the primary environmental problem caused by them is the

destruction of huge areas of forest. Gypsy moth caterpillars

687

defoliate a number of

species

of broadleaf trees including

birches, larch, and aspen, but prefer the leaves of several

species of oaks, though they have also been found to eat

some evergreen needles. One caterpillar can consume up to

one square foot of leaves per day. In 2001, 84.9 million acres

(34.4 million ha) had been defoliated by these insects. The

sheer number of gypsy moth caterpillars produced in one

generation can create other problems as well. Some areas

become so heavily infested that the insects have covered

houses and yards, causing psychological difficulties as well

as physical.

There are few natural predators of the gypsy moth in

North America, and none that can keep its population under

control. Attempts have been made since the 1940s to control

the insect with pesticides, including DDT, but these efforts

have usually resulted in further contaminating of the

envi-

ronment

without controlling the moths or their caterpillars.

Numerous attempts have also been made to introduce species

from outside the region to combat it, and almost 100 differ-

ent natural enemies of the gypsy moth have been introduced

into the northeast United States. Most of these have met,

at best, with limited success. Recent progress has been made

in experiments with a Japanese fungus that attacks and kills

the gypsy moth. The fungus enters the body of the caterpillar

through its pores and begins to destroy the insect from the

inside out. It is apparently non-lethal to all other species in

the infested areas, and its use has met with limited success

in parts of Rhode Island and upstate New York. It remains

unknown however, whether it will control the gypsy moth,

or at least stem the dramatic population increases and severe

infestations.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Pond, D., and W. Boyd. “Gypsy on the Move.” American Forests 98 (March–

April 1992): 21–25.

O

THER

Gypsy Moth in North America. September 15, 1998 [cited May 2002].

<http://www.fs.fed.us/ne/morgantown/4557/gmoth>.

Gypsy Moth in Virginia. April 10, 2001 [cited May 2002]. <http://www.gyp-

symoth.ento.vt.edu/vagm/index.html>.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Plant Protection and Quarantine: Gypsy

Moth Quarantine.” Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. June 15,

2001 [cited May 2002]. <http://www.aphis.usda.gov/ppq/maps/gyp-

moth.pdf>.

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

H

Arie Jan Haagen-Smit (1900 – 1977)

Dutch atmospheric chemist

The discoverer of the causes of

photochemical smog

,

Haagen-Smit was one of the founders of atmospheric chem-

istry, but first made significant contributions to the chemistry

of essential oils. Haagen-Smit was born in Utrecht, Holland,

in 1900, and graduated from the University of Utrecht. He

became head assistant in organic chemistry there and later,

served as a lecturer until 1936. He came to the United States

as a lecturer in biological chemistry at Harvard, then became

associate professor at the California Institute of Technology

in Pasadena. He retired as Professor of Biochemistry in

1971, having served as executive officer of the department

of biochemistry and director of the plant

environment

labo-

ratory. Haagen-Smit also contributed to the development of

techniques for decreasing

nitrogen

oxide formation during

combustion

in electric

power plants

and autos, and to

studies of damage to plants by

air pollution

.

While early workers on the

haze

and eye irritation

that developed in Los Angeles, California, tried to treat it

as identical with the

smog

(

smoke

+ fog) then prevalent

in London, England, Haagen-Smit knew at once it was

different. In his reading, Haagen-Smit had encountered a

1930s Swiss patent on a process for introducing random

oxygen functions into

hydrocarbons

by mixing the hydro-

carbons with nitrogen dioxide and exposing the mixture to

ultraviolet light. He thought this mixture would smell much

more like a smoggy day in Los Angeles than would some sort

of mixture containing

sulfur dioxide

, a major component of

London smog. He followed the procedure and found his

supposition was correct. Simple analysis showed the mixture

now contained

ozone

, organic peroxides, and several other

compounds. These findings showed that the sources of the

problems of Los Angeles were

petroleum

refineries,

petro-

chemical

industries, and ubiquitous

automobile

exhaust.

Haagen-Smit was immediately attacked by critics, who

set up laboratories and developed instruments to prove him

689

wrong. Instead the research proved him right, except in

minor details.

Haagen-Smit had a long and distinguished career. In

addition to his work on the chemistry of essential flower

oils and famous findings on smog, he also contributed to

the chemistry of plant hormones and plant alkaloids and the

chemistry of

microorganisms

. He was a founding editor

of the International Journal of Air Pollution, now known as

Atmospheric Environment, one of the leading air

pollution

research journals. Though he found the work uncongenial,

he stayed with it for the first year, then retired to the editorial

board, where he served until 1976.

Once it was obvious that he had correctly identified

the cause of the Los Angeles smog, he was showered with

honors. These included membership in the National Acad-

emy of Science, receipt of the Los Angeles County Clean Air

Award, the Chambers Award of the

Air Pollution Control

Association (now the

Air and Waste Management Associ-

ation

), the Hodgkins Medal of the Smithsonian Institution,

and the National Medal of Science. In his native Netherlands

he was made a Laureate of Labor by the Netherlands Chemi-

cal Society, and Knight of the Order of Orange Nassau.

[James P. Lodge Jr.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Lodge, J. P. “Obituary: A. J. Haagen-Smit.” Nature 267 (1977): 565–566.

Habitat

Refers to the type of

environment

in which an organism

or

species

occurs, as defined by its physical properties (e.g.,

rainfall, temperature, topographic position,

soil texture

,

soil

moisture) and its chemical properties (e.g., soil acidity, con-

centrations of nutrients and

toxins

, oxidation reduction sta-

tus). Some authors include broad biological characteristics in

their definitions, for instance forest versus

prairie

habitats,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Habitat conservation plans

referring to the different types of environments occupied by

trees and grasses. Within a given habitat there may be differ-

ent micro-habitats, for example the hummocks and hollows

on bogs or the different soil horizons in forests.

Habitat conservation plans

Protection of the earth’s

flora

and

fauna

, the myriad of

plants and animals that inhabit our planet, is totally depen-

dent upon preserving their habitats. This is because a

habi-

tat

, or natural

environment

for a specific variety of plant

or animal, provides everything necessary for sustaining life

for that

species

. Habitat

conservation

is part of a larger

picture involving interdependency between all living things.

Human life has been sustained since its dawning through

the utilization of both plants and animals for food, clothing,

shelter and medicines. It follows then that the destruction

of any specie’s environment, which will result in the eventual

destruction of the species itself, adversely affects us all.

Habitat destruction occurs for a number of reasons.

Human industry has usually resulted in

pollution

that has

often destroyed the balance of natural elements in

soil

, water

and air that are necessary to life. The need for forest products

such as lumber has threatened woodlands in more ways than

one. A lumbering practice called

clear-cutting

, in addition

to over-harvesting a forest, leaves behind barren ground that

results in

erosion

and threatens species dependent on the

vegetation that grows on the forest floor. This wearing away

of soil often results in negative changes to nearby streams

and thus the water supply to multitudes of living things.

The introduction of non-native species into an area can also

threaten a habitat, as plants and animals with no natural

enemies may thrive abnormally. This in turn will throw

off the delicate balance and natural biological controls on

population growth

that each environment provides for its

inhabitants.

As the understanding of these facts became more wide-

spread, the demand for habitat conservation throughout the

world increased. In the United States, in 1973, Congress

passed the

Endangered Species Act

to protect both at risk

species and their environments. In order to control activities

by private and non-federal government landowners that

might disturb habitats, the Act included a section outlining

Habitat Conservation Plans (HCPs).

These HCPs were not implemented without a good

deal of controversy. Some environmentalists were critical of

the plans, believing that they failed to actually preserve the

habitats and species they were designed to protect. Both

conservationists and landowners and industrialists argued

690

that these HCPs’ were based upon faulty science and invalid

and insufficient data. Impartial reviews did indicate that

there were flaws. One cited weakness was that a species

could theoretically be added to the endangered list but have

no modification made in the plan to protect that species’

living-space.

It is clearly a measure of this controversy that in the

law’s first twenty years, only fourteen such plans were devel-

oped and approved nationwide. During the administration

of President Bill Clinton, the federal government revised

policies to encourage more numerous and more effective

HCP applications. A more responsive to change “No sur-

prises" policy helped encourage participation in habitat con-

servation plans.

This policy recognizes that

natural resources

change

and environments require continual monitoring and alter-

ations in plans, that those trying to balance environments

can do so with

adaptive management

. Such alterations

encouraged participation in HCPs, and by 1997, more than

200 plans covering nine million acres of land had been

approved. As of April of 2002, the United States

Fish and

Wildlife Service

notes that nearly double that number, 379

plans covering nearly 30 million acres and protecting more

than 200 endangered and threatened species have now been

approved.

One positive example of the possibilities created by

such plans is the work of the Plum Creek Timber Company,

a nationwide timberland company whose corporate offices

are located in Seattle, Washington. Self-described as “the

second largest private timberland owner in the United States,

with 7.8 million acres located in the northwestern, southern

and northeastern regions of the country”, the company lists

many initiatives it has undertaken to preserve the environ-

ments under its charge. In the early 1990’s, Plum Creek

Timber Company developed a plan to provide a ladder-like

framework in Coquille River tributaries in Oregon to aid

fish in reaching upper areas blocked for many years by a

culvert. Spawning surveys completed the next year showed

that coho

salmon

and steelhead trout, for the first time in

forty years, were present above the culvert.

HCPs were created to focus attention on the problem

of declining

wildlife

on land not owned and protected by

the federal government and to attempt to maintain the

bio-

diversity

so necessary for all life. This goal would ideally

assure that land is developed in such a way that it serves

both the needs of the landowner and of threatened wildlife.

However, in reality, it is not always possible to achieve

such a goal. Often the more appropriate aim, if habitat

conservation is to be successful, will be total protection of

a wildlife environment even at the price of banning all devel-

opment.

[Joan M. Schonbeck]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Habitat fragmentation

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gilbert Oliver L., and Penny Anderson. Habitat Creation and Repair.New

York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Walters, C. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources.New York: Mac-

Millan, 1986.

P

ERIODICALS

Mann, C., and M. Plummer. “Qualified Thumbs Up for Habitat Plan

Science.” Science 278, no. 5346 (December 19, 1997): 2052.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Fish and Wildlife Reference Service, 54300 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110,

Bethesda, MD USA 20814 (301) 492-6403, Toll Free: (800) 582-3421,

Email: fw9fareferenceservice@fws.gov, <http://www.lib.iastate.edu/

collections/db/usfwrs.html>

National Wildlife Federation, 111000 Wildlife Center Drive, Reston, VA

USA 20190 (703)438-6000, Toll Free: (800) 822-9919, Email:

info@nwf.org, <http://www.nwf.org>

Habitat fragmentation

The

habitat

of a living organism, plant, animal, or microbe,

is a place, or a set of environmental conditions, where the

organism lives. Net loss of habitat obviously has serious

implications for the survival and well-being of dependent

organisms, but the nature of remaining habitat is also very

important. One factor affecting the quality of surviving habi-

tat is the size of remaining pieces. Larger areas tend to be

more desirable for most

species

. Various influences, often

a result of human activity, cause habitat to be divided into

smaller and smaller, widely separated pieces. This process of

habitat fragmentation has profound implications for species

living there.

Each patch created when larger habitat areas are frag-

mented results in more edge area where patches interface

with the surrounding

environment

. These smaller patches

with a relatively large ratio of edge to interior area have

some unique characteristics. They are often distinguished

by increased predation when predators are able to hunt or

forage along this edge more easily. The decline of songbirds

throughout the United States is due in part to the increase

of the brown-headed cowbird competing with other birds

along habitat edges. The cowbird acts as a parasite by laying

its eggs in other birds’ nests and leaving them for other

birds to hatch and raise. After hatching, the young cowbirds

compete with the smaller birds of the nest, almost always

killing them.

In the smaller patches formed from fragmentation,

habitat is less protected from adverse environmental events,

and a single storm may destroy the entire area. A disease

outbreak may eliminate the entire population. When the

number of breeding adults becomes very low, some species

can no longer reproduce successfully.

691

Some songbirds found in the United States are declin-

ing in number as their habitat shrinks or disappears. When

they migrate south in the winter they find that habitat is

more scarce and fragmented. When they return from the

tropics in the spring, they discover that the nesting territory

that they used the previous year has disappeared.

Species dispersal is decreased as organisms must

travel farther to go from one habitat area to another,

increasing their exposure to predation and possibly harmful

environmental conditions. Populations become increasingly

insular as they become separated from related populations,

losing the genetic benefits of a larger interbreeding popu-

lation.

Road building often divides habitat areas, seriously

disrupting

migration

of some mammals and herptiles

(

frogs

, snakes, and turtles). Large swaths of land used by

modern freeways are particularly effective in this regard. In

earlier times, railroads built across the Great Plains to con-

nect the west coast of the United States with states east of

the Mississippi, divided

bison

habitat and hampered their

migration from one grazing area to another. This was one

of the factors that led to their near

extinction

.

Habitat fragmentation, usually a result of human activ-

ity, is found in all major habitat types around the world.

Rain forests,

wetlands

,

grasslands

, and hardwood and

conifer forests are all subject to various degrees of fragmenta-

tion. Globally, rain forests are currently by far the most

seriously impacted

ecosystem

. Because they contain 50%

or more of the world’s species, the resulting number of

species extinctions is particularly disturbing. It is estimated

that 25% of the world’s rainforests disappeared during the

twentieth century, and another 25% were seriously frag-

mented and degraded. In the last two centuries, nearly all

of the

prairie

grassland once found in the United States has

disappeared. Remaining remnants occur in small, scattered,

isolated patches. This has resulted in the extinction or near

extinction of many plant and animal species.

Ability to survive habitat fragmentation and other en-

vironmental changes varies greatly among species. Most find

the stress overwhelming and simply disappear. A few of the

common species that have been very successful in adapting

to changing conditions include animals such as the opossum,

raccoon, gray squirrel, and European starling. Plant examples

include dandelions, crab grass, creeping Charlie, and many

other weed species. The wetland invader,

purple loos-

estrife

, originally imported from Europe to the United

States, is rapidly spreading into disrupted habitat previously

occupied by native emergent aquatic vegetation such as reeds

and cattails. Animal species that once found a comfortable

home in cattail stands must move on.

[Douglas C. Pratt Ph.D.]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Cunningham, W. P., and Cunningham, M. A. Principals of Environmental

Science: Inquiry and Applications. McGraw-Hill, 2002.

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel

(1834 – 1919)

German naturalist, scientist, biologist, philosopher, and

professor

Ernst Haeckel was born in Potsdam, Germany. As a young

boy he was interested in

nature

, particularly botany, and

kept a private herbarium, where he noticed that plants varied

more than the conventional teachings of his day advocated.

Despite these natural interests, he studied medicine—at his

father’s insistence—at Wu

¨

rzburg, Vienna, and Berlin be-

tween 1852 and 1858. After receiving his license he practiced

medicine for a few years, but his desire to study pure science

won over, and he enrolled at the University of Jena to study

zoology. Following completion of his dissertation, he served

as professor of zoology at the university from 1862 to 1909.

The remainder of his adult life was devoted to science.

Haeckel was considered a liberal non-conformist of

his day. He was a staunch supporter of Charles Darwin, one

of his contemporaries. Haeckel was a prolific researcher and

writer. He was the first scientist to draw a “family tree” of

animal life, depicting the proposed relationships between

various animal groups. Many of his original drawings are

still used in current textbooks. One of his books, The Riddle

of the Universe (1899), exposited many of his theories on

evolution

. Prominent among these was his theory of recapit-

ulation, which explained his views on evolutionary vestiges

in related animals. This theory, known as the Biogenic Law,

stated that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—the devel-

opment of the individual (ontogeny) repeats the history of

the race (phylogeny). In other words, he argued that when an

embryo develops, it passes through the various evolutionary

stages that reflect its evolutionary ancestry. Although this

theory was widely prevalent in biology for many years, scien-

tists today consider it inaccurate or only partially correct.

Some even argue that Haeckel falsified his diagrams to prove

his theory.

In

environmental science

, Haeckel is perhaps best

known for coining the term

ecology

in 1869, which he

defined as “the body of knowledge concerning the economy

of nature—the investigation of the total relationship of the

animal both to its organic and its inorganic

environment

including, above all, its friendly and inimical relations with

those animals and plants with which it directly or indirectly

comes into contact—in a word, ecology is the study of all

692

Ernst Haeckel. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

those complex interrelations referred to by Darwin as the

conditions for the struggle for existence.”

[John Korstad]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gasman, D. The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism

in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League. New York: American

Elsevier, 1971.

Hitching, F. The Neck of the Giraffe: Darwin, Evolution, and the New

Biology. Chula Vista, CA: Mentor, 1982.

Smith, R. E. Ecology and Field Biology. 4th ed. New York: Harper and

Row, 1990.

Half-life

A term primarily used to describe the physical half-life, how

radioactive decay

processes cause unstable atoms to be

transformed into another element, but can also refer to the

biological half-life of substances that are not radioactive.

Specifically, the physical half-life is the time required

for half of a given initial quantity to disappear (or be con-

verted into something else). This description is useful be-

cause radioactive decay proceeds in such a way that a fixed

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Halons

percentage of the atoms present are transmuted during a

given period of time (a second, a minute, a day, a year).

This means that many atoms are removed from the popula-

tion when the total number present is high, but the number

removed per unit of time decreases quickly as the total num-

ber falls.

For all practical purposes, the number of radioactive

atoms in a population never reaches zero because decay

affects only a fraction of the number present. Some infinitesi-

mal number will still be present even after an infinite number

of half-lives because with each time period half of what was

present before decays and is lost from the sample. Therefore,

determining the point at which half of the original number

disappears (the half-life) is usually the most accurate way of

describing this process. See also Radioactivity

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

see

Bald eagle

Halons

Halons are

chemicals

that contain

carbon

, fluorine, and

bromine

. They are used in fire extinguishers and other

firefighting equipment. Because of their bromine content,

halons can destroy

ozone

molecules(O

3

) very effectively,

thereby contributing to the depletion of ozone and the cre-

ation of holes in the ozone layer of the

stratosphere

. The

ozone layer is located 10–28 mi (16–47 km) above the surface

of the earth and it protects humans and the

environment

from the Sun’s ultraviolet-B radiation. Halons account for

approximately 20% of the ozone depletion.

Halons have been used since the 1940s, when they

were discovered by U.S. Army researchers looking for a fire-

extinguishing agent to replace carbon tetrachloride. Halons

are very effective against most types of fires, are nonconduc-

tive, and dissipate without leaving a residue. They are also

economical, very stable, and safe for human use.

Halons consist of carbon atom chains with attached

hydrogen

atoms that are replaced by the halogens fluorine

(F)and bromine (Br). Some also contain

chlorine

(Cl). Ha-

lon-1211 ((bromochlorodifluoromethane, CF

2

ClBr), halon-

1301 (bromotrifluoromethane, CF

3

Br), and halon-2402 (di-

bromotetrafluoroethane, C

2

F

4

Br

2

) are the major fire-sup-

pressing halons. Halon-1211 is discharged as a liquid and

vaporizes into a cloud within a few feet. Halon-1301 is

stored as a liquid but discharges as a gas. Halons suppress

fires because they bond with the free radicals and intermedi-

ates of the decomposing fuel molecules that propagate fire,

thus rendering the fuel inert. They also lower the tempera-

ture the fire.

693

Halons may take up to seven years to drift up and

distribute themselves throughout the stratosphere, with the

highest concentrations over the poles. High-energy

ultravi-

olet radiation

breaks their bromine and chlorine bonds thus

releasing these very reactive halogen molecules, which in

turn break down the ozone molecules and react with free

oxygen to interfere with ozone creation. Although chlorine

is more abundant, bromine is more than 100 times more

damaging to ozone.

Halons are categorized as class I ozone-depleting sub-

stances, along with

chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs) and other

substances with ozone-depleting potentials (ODPs) of 0.2

or greater. The Ozone Depletion Potential(ODP)is a num-

ber that refers to the amount of ozone depletion caused

by a substance. Halon-1211 has an ODP of 3.0 and an

atmospheric lifetime of 11 years. It also has a global warming

potential (GWP) of 1300. Halon-1301 has an ODP of 10.0,

an average lifetime of 65 years, and a GWP of 5600 to 6900.

Halon-2402 has an ODP of 6.0. In contrast, CFC-11, a

common refrigerant, has an ODP of 1. Halon-1211 and

halon-1301 are the most common halons in the United

States. Halon-2402 is widely used in Russia and the devel-

oping world. Although total halon production between 1986

and 1991 accounted for only about 2% of the total production

of class I substances, it accounted for about 23% of the ozone

depletion caused by class I substances.

Halon production in the United States ended on De-

cember 31, 1993 because they contribute to ozone depletion.

Under the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Sub-

stances, first negotiated in 1987 and now including more

than 172 countries, halons became the first ozone-depleting

substances to be phased out in industrialized nations, with

production stopped in 1994. Under the

Clean Air Act

, the

United States banned the production and importation of

halons as of January 1, 1994. The use of existing halons in

fire protection systems continues and recycled halons can be

purchased to recharge such systems. It is estimated that

about 50% of all halons ever produced currently exist in

portable fire extinguishers and firefighting equipment. The

United States holds 40% of the world’s supply of halon-

1301. In 1997, approximately 1,080 tons (977 metric tons)

of halon-1211 and 790 tons (717 metric tons) of halon-

1301 were released in the United States. In 1998, the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) prohibited the

venting of halons during training, testing, repair, or disposal

of equipment, and banned the blending of halons, to prevent

the accumulation of nonrecyclable stocks.

The

European Union

has gone beyond the Montreal

Protocol, banning the sale and non-critical use of halons after

December 31, 2002, and requiring the decommissioning of

non-critical halon systems by December 31, 2003.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hanford Nuclear Reservation

Halon production and consumption continues in de-

veloping countries, especially China, the Republic of Korea,

India, and Russia. Under the Montreal Protocol, developing

countries were to freeze halon consumption by January 2002.

A 50% reduction in halon consumption is required by Janu-

ary 2005 and the complete halt of halon production and use

is slated for January 2010. However halon-1211 emissions

increased by about 25% between 1988 and 1999. Since most

of the increased manufacture and release of halon-1211 oc-

curs in China, the

United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme

is helping China to phase-out production by 2006.

Atmospheric levels of halon-1202, which is not cov-

ered by the Montreal Protocol, increased fivefold between

the late 1970s and 1999, and by 17% annually in the late

1990s. It is not known whether this increase is a byproduct

of the inefficient production of other halons in developing

countries or whether some countries are manufacturing it

for military applications. Halon-1202’s ODP is about one-

half that of the common CFCs.

Alternatives are now available for most halon applica-

tions. Existing halon supplies from fire suppression systems

are being recycled for critical uses where no alternative exists.

[Margaret Alic Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Peterson, Eric. Standards and Codes of Practice to Eliminate Dependency on

Halons: Handbook of Good Practices in the Halon Sector. Paris: United Nations

Environment Programme, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Chang, Lisa. “Regulating Halon Emissions.” NFPA Journal 93, no. 4 (July/

August 1999): 90.

Poynter, Ronald J. “Halon Replacements: Chemistry and Applications.”

Professional Safety 44, no. 3 (March 1999): 46–50.

Zurer, Pamela. “Slow Road to Ozone Recovery.” Chemical and Engineering

News 77, no. 17 (April 26, 1999): 8–9.

O

THER

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ozone Depletion. May 15, 2002

[cited May 19, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/ozone/index.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Halon Alternatives Research Corporation, Halon Recycling Corporation,

2111 Wilson Boulevard, Eighth Floor, Arlington, VA USA 22201 (703)

524-6636, Fax: (703) 243-2874, Toll Free: (800) 258-1283, Email:

harc@harc.org, <http://www.harc.org>

Stratospheric Ozone Information Hotline, United States Environmental

Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C.

USA 20460 (202) 775-6677, Toll Free: (800) 296-1996, Email: public-

access@epa.gov, <http://www.epa.gov/ozone>

United Nations Environment Programme, Division of Technology,

Industry and Economics, Energy and OzonAction Programme, Tour

Mirabeau, 39-43 quai Andre

´

Citroe

¨

n, 73759 Paris Cedex 15, France (33-

1) 44 37 14 50, Fax: (33-1) 44 37 14 74, Email: ozonaction@unep.fr,

<http://www.uneptie.org/ozonaction<

694

Hanford Nuclear Reservation

The Hanford Engineering Works was conceived in June

1942 under the direction of Major General Leslie R. Groves,

head of the famous Manhattan Project, to produce

pluto-

nium

and other materials for use in the development of

nuclear weapons

. By December 1942, a decision was

reached to proceed with the construction of three plants—

two to be located at the Clinton Engineering Works in

Tennessee and a third at the Hanford Engineering Works

in Washington.

Hanford was established in the southeastern portion

of Washington state between the Yakima Range and the

Columbia River, about 15 mi (24 km) northwest of Pasco,

Washington. The site occupies approximately 586 mi

2

(1,517 km

2

)of

desert

with the Columbia River flowing

through its northern region. Once a linchpin of United

States nuclear weapons production during the Cold War era,

Hanford has now become the world’s largest environmental

cleanup project.

Hanford Engineering Works, known as HEW or “site

W” in classified terms, was originally under the control of

the Manhattan District of the

Army Corps of Engineers

(MED) until the

Atomic Energy Commission

(now the

Department of Energy, DOE) took over in 1947. The actual

operation of the site has been managed by a series of contrac-

tors since its inception. The first organization granted a

contract to run site operations at Hanford was E.I. DuPont

de Nemours and Company. In 1946, General Electric took

over, and with the aid of several subcontractors ran construc-

tion and operation of the site through 1965. A series of

contractors have directed operations at both the main DOE-

Richland Operations Office and the DOE-Office of River

Protection (ORP), the agency responsible for overseeing

hazardous waste

tank farm clean up along the Columbia

River, since then.

In 1965, Battelle Memorial Institute, a non-profit or-

ganization, assumed management of the federal govern-

ment’s DOE research laboratories on the Hanford Site. The

newly formed Pacific Northwest Laboratory (which became

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, or PNNL, in 1995)

supports the Hanford site cleanup through the development

and testing of new technologies. Battelle still runs the PNNL

today.

A number of contractors have directed operations at

HEW throughout its history. As of early 2002, the prime

contractors at the DOE-Richland Operations Office in-

cluded Battelle Memorial Institute (BMI); Bechtel Hanford,

Inc.(BHI); Fluor Hanford, Inc. (FHI); and the Hanford

Environmental Health

Foundation (HEHF). The DOE-

Office of River Protection (ORP), responsible for overseeing

hazardous waste tank farm clean up along the Columbia

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hanford Nuclear Reservation

River, is managed by prime contractors CH2M Hill Hanford

Group, Inc. (CHG) and Bechtel National, Inc. (BNI).

Over the period from 1943 to 1963, a total of nine

plutonium-production reactors and five processing centers

were built at Hanford, with the last of the reactors ceasing

operations in 1987 (permanent shut-down of the Fast Flux

Test Facility [FFTF], a sodium-cooled breeding reactor that

produced isotopes for medical and industrial use, was ordered

to close in 2001). Plutonium produced at Hanford was used

in the world’s first atomic explosion at Alamogordo, New

Mexico in 1945. The Hanford Site processed an estimated

74 tons of plutonium during its years of active operation,

accounting for approximately two-thirds of all plutonium

produced for United States military use.

The plutonium fuel was processed on site at the Pluto-

nium and

Uranium

Extraction Plant (PUREX). In the pro-

cessing of plutonium, a substantial quantity of

radioactive

waste

is produced; at Hanford, it amounts to 40% of the

nation’s one billion Curies of

high-level radioactive waste

from weapons production. PUREX ceased regular produc-

tion in 1988 and was officially closed in 1992. Deactivation

of the plant was completed in 1997.

During the HEWs operational lifetime, some high-

level radioactive wastes were diverted from the relatively

safe underground storage to surface trenches. Lower-level

contaminated water was also released into ditches and the

nearby Columbia River. The DOE reports that over 450

billion gallons of waste liquid from the Hanford plants was

improperly discharged into the

soil

column during their

operational lifetime. These wastes contained cesium-137,

technetium-99, plutonium-239 and -240, strontium-90, and

cobalt-60. So much low-level waste was dumped that the

groundwater

under the reservation was observed to rise by

as much as 75 ft (23 m).

Today more than 50 million gal (189.3 million l) of

high-level radioactive waste is contained in approximately

177 underground storage tanks, 67 of which have known

leaks. One million gallons (3.8 million l) of this tank waste

has already leaked into the surrounding ground and ground-

water. An estimated 25 million ft

4

of radioactive solid wastes

remains buried in trenches which are similar to septic-tank

drainage

fields. Spent nuclear fuel basins have leaked over

15 million gal (56.8 million l) of radioactive waste. In total,

over 1,900 waste sites and 500 contaminated facilities have

been identified for clean up at Hanford. The contaminated

zone encompasses a variety of ecosystems and the nearby

Columbia River.

In the early 1990s, Congress passed a bill requiring

the DOE to create a watchdog list of those Hanford tanks

at risk for explosion or other potential release of high-risk

radioactive waste. By 1994, the list had 56 tanks listed as a

high-risk potential. By late 2001, the final 24 tanks had

695

been removed from the congressional watch list, which is

sometimes referred to as the “Wyden Watch List” (after

sponsoring Senator Ron Wyden).

In 1989, the DOE, U.S.

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA), and the State of Washington Department

of Ecology signed the Hanford Federal Facility Agreement

and Consent Order ("Tri-Party Agreement"). The Tri-Party

Agreement (TPA) outlines cleanup efforts required to

achieve compliance with the Comprehensive Environmental

Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA; or

Superfund) and the

Resource Conservation and Recovery

Act

(RCRA).

Compliance with federal and state authorities under

the TPA has not always progressed without problems for

Hanford officials. The EPA fined DOE for poor

waste

management

practices in 1999, levying $367,078 in civil

penalties that were later reduced to $25,000 and a promise

to spend $90,000 on additional clean-up activities. The fol-

lowing year EPA issued an additional $55,000 fine against

the DOE for non-compliance with the Tri-Party agreement.

However, the five-year review of the project completed by

EPA in 2001, while specifying 18 “action items” for DOE

compliance, also states that cleanup of soil waste sites and

burial grounds “are proceeding in a protective and effective

manner.” In March 2002, DOE was fined $305,000 by

the Washington Department of Ecology for failing to start

construction of a waste treatment facility as outlined in the

Tri-Party agreement. As of May 2002, the State had agreed

to forgive the fine if the DOE began construction on the

facility by the end of the year.

Even though the Hanford site poses significant envi-

ronmental concerns, the facility has generated a number

of innovative technological advances in the clean up and

immobilization of radioactive wastes. For instance, one pro-

cess developed in Hanford’s Pacific Northwest Laboratory

is in situ vitrification, which uses electricity to treat waste

and surrounding

contaminated soil

, melting it into a glass

material that is more easily disposed. The William R. Wiley

Environmental and Molecular Sciences Laboratory

(EMSL), which opened in 1997, houses a wide range of

experimental programs aimed at solving nuclear waste treat-

ment issues.

And despite the extent of its contamination, the isola-

tion and security of the Hanford site has made the area

home to a large and diverse population of

flora

and

fauna

.

A 1997 Nature Conservancy study at Hanford found dozens

of previously undiscovered and rare plant and animal

species

in various site habitats. The

biodiversity

study led to the

establishment of the federally-protected 195,000-acre

(79,000-ha) Hanford Reach National Monument in June

2000.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Garrett Hardin

In May 2002 Department of Energy officials intro-

duced a “Performance Management Plan for the Accelerated

Cleanup of the Hanford Site.” The new plan sets signifi-

cantly revised goals for the completion of the site cleanup,

setting some projects ahead 35 years or more. While the

plan was still in its draft stage at the writing of this entry,

DOE officials anticipate its approval by the end of 2002.

Strategic initiatives outlined in the plan include restoration

of the Columbia River Corridor by 2012 and completion of

tank decontamination and closure by 2035.

[Paula A Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gerber, Michele S. On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford

Nuclear Site, 2nd edition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

P

ERIODICALS

“Three-Way Agreement Reduces Length of Required Cleanup Time.”

Hazardous Waste Superfund Week 24, no. 12 (March 25, 2002).

“Washington State Freezes Fine Against Hanford Nuclear-Cleanup Site.”

Tri-City Herald, March 12, 2002 [cited May 2002]. <http://www.tri-cityh-

erald.com/news/2002/0312/story4.html>.

O

THER

Washington State Department of Ecology Nuclear Waste Program. [cited May

2002]. <http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/nwp>.

United States Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office and

Office of River Protection. Performance Management Plan for the Accelerated

Cleanup of the Hanford Site. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.hanford.gov/

docs/hpmp/hpmp.pdf>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Department of Energy, Hanford Site, Richland Operations Office,

Freedom of Information Office, 825 Jadwin Avenue, P.O. Box 550,

Richland, WA USA 99352 (509) 376-6288 , Fax: (509)376-9704 , Email:

FOIA@rl.gov, <http://www.hanford.gov/FOIA/index.cfm>

Dr. Garrett Hardin (1915 – )

American environmentalist and writer

Trained as a biologist (University of Chicago undergraduate

degree; Ph.D. from Stanford in 1942 in microbial

ecology

)

Garrett Hardin spent most of his career at the University

of California at Santa Barbara, where his title was Professor

of

Human Ecology

. He was born in Dallas, Texas, and grew

up in various places in the Midwest, spending summers on

his grandparents’ farm in Missouri.

Very few biologists, short of Charles Darwin, have

generated the levels of controversy that Hardin’s thinking

and writing have. The controversies, which continue today,

center on two metaphors of human-ecological relationships;

“the tragedy of the commons” and “the lifeboat ethic.”

Hardin is widely credited with inventing the idea of

the

tragedy of the commons

, but his work was long pre-

696

ceded by an ancient rhyme about the tragedy that results from

stealing the commons from the goose. He did popularize the

idea, though, and it made him a force to reckon with in

population studies. Seldom is an academic author so identi-

fied with one article (though his thoughts on lifeboat ethics

have since become almost equal in identification and impact).

The idea is very simple: resources held in common will be

exploited by individuals for personal gain in disregard of

public impacts; individual profit belongs to individual ex-

ploiters while they bear the brunt of only part of the impacts.

Much of the controversy centers on Hardin’s solutions to

the tragedy: first, that private property owners “recognize

their responsibility to care for” the land, thus lending at

least implicit support to privatization efforts and second, the

paradoxical idea that since exercise of individual freedom

leads to ruin, such freedom cannot be tolerated, thus we

must turn to “mutual coercion mutually agreed upon.” As

Hardin noted, “if everyone would restrain himself, all would

be well; but it takes only one less than everyone to ruin a

system of voluntary restraint. In a crowded world of less

than perfect human beings, mutual ruin is inevitable if there

are no controls. This is the tragedy of the commons.” Hardin

has since expanded on his thesis, answering his critics by

incorporating the differences between an open access system

and an closed one. But the debate continues.

His other widely debated metaphor was of a lifeboat

(standing for a nation’s land and resources) occupied by rich

people in an ocean of poor people (who have fallen out of

their own, inadequate lifeboats). If the rich boat is close to

its margin of safety, what should its occupants do about the

poor people in the ocean? Or in the other boats? If the

occupants let in even a few more people, the boat may be

swamped, thus creating an ethical dilemma for the rich

occupants. How do these occupants of the already full life-

boat justify taking in additional people if it guarantees the

collapse for all? Ever since, Hardin has been accused of social

Darwinism, of racism, of ignoring the possibility that “the

poverty of the poor may be caused in part by the affluence

of the rich,” and of isolationism (since he argued that “for

the foreseeable future survival demands that we govern our

actions by the ethics of a [sovereign] lifeboat” rather than

“space-ship” ethics that [arguably] try to care for all equi-

tably).

What Hardin was trying to do in both of these cases

was to look unemotionally at

population growth

and re-

source use, employing the rationale and language of a scien-

tist viewing human populations in an objective, evolutionary

perspective. Biologists know that “natural” populations that

overuse their resources, that exceed the

carrying capacity

of their range, are then adjusted—in numbers or in resource

use levels—also naturally and often brutally (from the per-

spective of many people). The problems remain that the