Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Monsoon

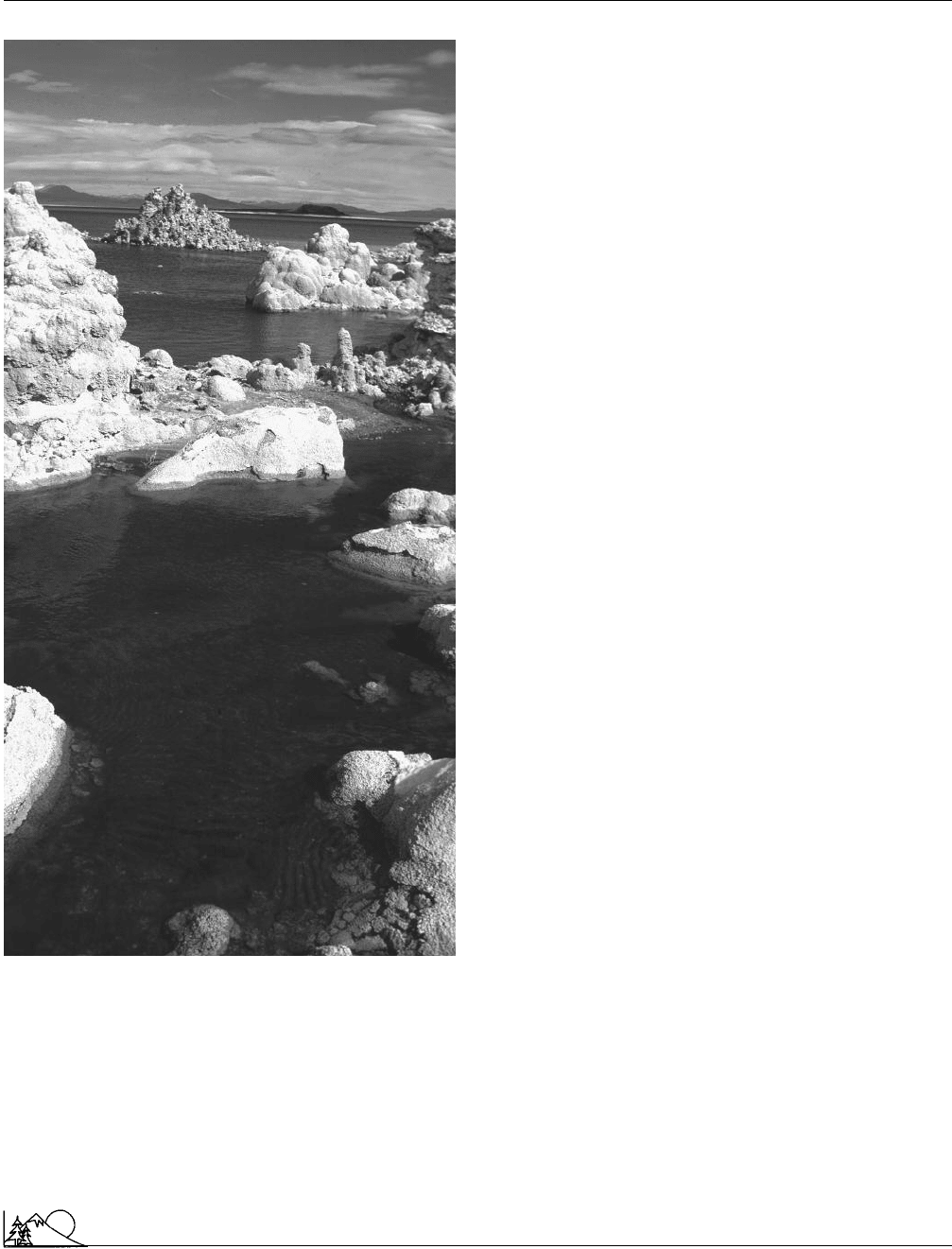

A view of frost covered rocks in Mono Lake,

California. (Photograph by R. Rowan. Photo Researchers

Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

the United States Congress established the Mono Basin

National Forest

Scenic Area.

Ultimately, the demand for water by Los Angeles

clashed with the demands of environmental groups, who

sought to maintain Mono Lake’s

ecological integrity

and

917

the fish habitat of streams feeding the lake. Lawsuits have

been fought in state and federal courts, and in 1989 Califor-

nia’s State Supreme Court ordered the Los Angeles Depart-

ment of Water and Power (LADWP) to reduce the amount

of water it was diverting from the lake. In 1993, the State

Water Resources

Control Board recommended that the

diversion be cut again, this time by half. LADWP has dis-

agreed, arguing that Los Angeles needs the water and that

the reduction is neither ecologically necessary nor economi-

cally wise.

The war over eastern Sierra water began at the turn

of the twentieth century, when Los Angeles acquired rights

to water previously used by farmers and ranchers in the

Owens Valley, just south of Mono Lake. By mid–century

the battleground had spread north to Mono Basin, and the

war promises to continue well into the next century. See

also Drinking-water supply; Hydrologic cycle; Los Angeles

Basin; National forest; Water allocation; Water resources;

Water rights

[Ronald D. Taskey]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lane, P. H., and A. Rossmann. “Owens Valley Groundwater Conflict.”

In Deepest Valley, edited by Genny Smith. Los Altos, CA: William Kauf-

mann, 1978.

Patten, D. T. The Mono Basin Ecosystem. Washington, DC: National Acad-

emy Press, 1987.

Monoculture

The agricultural practice of planting only one or two crops

over large areas. In the United States, corn and soybean are

the only crops grown on most farms in the central Midwest,

while on the Great Plains wheat is almost exclusively grown.

Although it minimizes farmers’ investments in large, expen-

sive implements, the practice exposes crops to the risk of

being wiped out by a single predator. This happened with

the Irish potato blight of the 1840s and the corn leaf blight

of 1970 in the United States, which destroyed millions of

acres of corn. Ecologists warn against monoculture’s over-

simplification of the

food chain/web

, arguing that complex

webs are more stable.

Monsoon

Monsoon (from Arabic, mausim, season) technically means

a reversal of winds, that point between the dry and the wet

seasons in tropical and subtropical India, Southeast Asia,

and parts of Africa and

Australia

, when seasonal winds

change their direction. When the land heats up, the hot air

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer

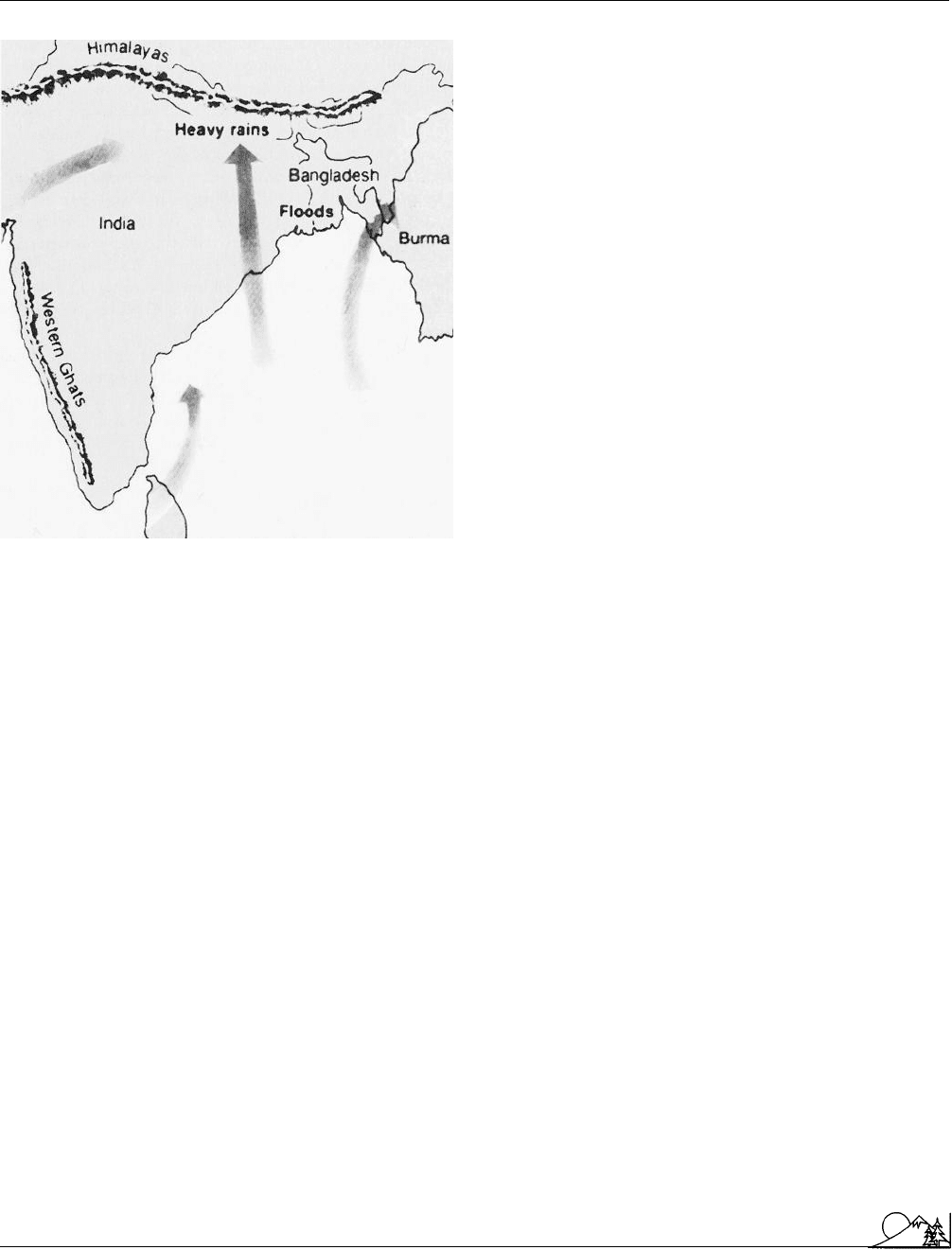

Each summer, warming air rises over the plains

of central India, creating a low-pressure cell

that draws in warm, moisture-laden air from

the ocean. Rising over the Western Ghats or the

Himalayas, the air cools causing heavy mon-

soon rains. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

rises, causing a low pressure zone that sucks in moisture-

filled cooler ocean air, creating clouds and producing rain.

In winter, the opposite happens: warm air over the ocean

rises and makes a low pressure zone that draws the cooler

air off the land.

Although monsoon winds have always been watched

by traders and sailors in the Eastern Hemisphere, their arrival

is critical to millions of people who depend on agriculture.

Cultural and religious customs, especially in India and south-

east Asia, are tied to the monsoon rains that bring a season

of fertility after a long hot and sterile dry period.

Coastal radar and satellites aid in weather prediction,

but the climatological components of monsoons are complex.

Tied to the heat and moisture exchange between land and

oceans, their effect can be altered by changes in the circula-

tion of hemispheric winds at the equator, as well as by

precessional changes in the orbit of the earth.

Environmental changes such as

deforestation

or

soil

erosion

can invite severe

flooding

, as in Bangladesh during

the 1980s. Scientists believe a rise in sea surface temperature

in the Atlantic Ocean, possibly related to the

greenhouse

918

effect

, prevented the monsoon rain from reaching the Afri-

can

Sahel

and contributed to recent droughts. This ocean

temperature rise may also be tied to the

El Nin

˜

o

event in

the Pacific Ocean.

Any fluctuations in monsoon rain patterns can cause

disease and death, along with millions of dollars in damage.

If the rains are delayed, or never come, or fall too heavily in

the beginning or at the end of the growing season, disastrous

results often follow. See also Climate; Cloud chemistry; Me-

teorology

Montreal Protocol on Substances That

Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987)

A historical agreement made in 1987 by members of the

United Nations to phase out substances that are harmful to

the earth’s

ozone

layer. The ozone layer protects life on

earth by blocking out the sun’s harmful

ultraviolet radia-

tion

. Since the 1970s scientists have documented the deple-

tion of the ozone by

chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs), com-

monly used for refrigeration and as solvents and

aerosol

propellants

. Alarmed by this growing global trend, scien-

tists and policymakers urged a decrease in the use and pro-

duction of CFCs as well as other ozone-damaging

chemi-

cals

. Ratifying the 1987 Montreal Protocol was a difficult

process, however, with the European Community, the for-

mer Soviet Union, and Japan reluctant to pose strict controls

on chemicals reduction. United States, Canada, Norway,

and Sweden, among others, favored stronger control and

negotiated with these nations to cut back and eventually

phase out completely ozone-depleting substances.

An amendment of the Montreal Protocol was made

in 1990 by 93 nations, including China and India, who had

not previously participated, to eliminate the use of CFCs,

carbon

tetrachloride, and halon gases by the year 2000 and

eliminate the production of methyl chloroform by 2005.

Some countries, like the United States, accelerated the

schedule to 1995. This 1990 amendment also established the

“Montreal Protocol Multilateral Fund” to help developing

countries become less dependent on ozone-depleting chem-

icals.

In November 1992 delegates from all over the world

met again in Copenhagen, Denmark, to further revise the

Montreal Protocol and accelerate the phase-out of ozone-

damaging substances and regulate three additional chemi-

cals. Some of those provisions were as follows: phase out

production of CFCs and carbon tetrachloride by 1996; ban

halons

by 1994 (the production of halogen was ended in

1994 in most industrialized nations and is expected to be

halted in China, Korea, India, and the former Soviet Union

by 2010); end production of methyl chloroform by 1996;

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mount Pinatubo

control the use of hydrochloroflurocarbons (HCFCs) and

eliminate them by 2030; and increase funding for the Multi-

lateral Fund (between $340 and $500 million by 1996).

Since the Copenhagen Amendments there have been

other amendments, such as the Montreal Amendment of

1997, which according to the Journal of Environmental

Law & Policy “adjusted the timetable for phaseout of some

substances and modified trade restrictions, including the

creation of a licensing system to attempt to decrease the

black market in ozone depleting substances;” and the Beijing

Amendment in 2002, which closely monitors bromochloro-

methane and the trade of hydrochloroflurocarbons.

As of July 2002, 175 nations have ratified the Montreal

Protocol. However, while countries have volunteered to con-

trol ozone-damaging chemicals, individual companies can

still produce the banned chemicals for “essential uses and

for servicing certain existing equipment.” The Alliance for

Responsible CFC Policy in Arlington, Vermont, praised

the concession for balancing environmental and economic

concerns. Others, such as members of the

Friends of the

Earth

, decry the provision as a “big loophole” that under-

mines the initiative of the Montreal Protocol. See also Ozone

layer depletion

[Kyung-Sun Lim]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Benedick, R.E. “Ozone Diplomacy.” Issues in Science and Technology 6 (Fall

1989): 43–50.

DeSombre, Elizabeth R. “The Experience of the Montreal Protocol: Partic-

ularly Remarkable, and Remarkably Particular.” UCLA Journal of Environ-

mental Law & Policy 19, no. 1 (Summer 2001): 49.

“EU/UN: Change to Montreal Protocol Outlawing HCFCS due to Enter

into Force.” European Report (January 9, 2002): 515.

“Ozone-Protection Treaty Strengthened.” Science News 142 (December 12,

1992): 415.

More developed country

The terms more developed countries (MDCs) and

less de-

veloped countries

(LDC) were coined by economists to

classify the world’s 183 countries on the basis of economic

development (average annual per capita income and gross

national product). The 33 countries (including the United

States, Canada, Japan,

Australia

, New Zealand and all the

western European countries) in the MDC group are wealthy

and industrially-developed. They tend to have temperate

climates and fertile soils. About 23 percent of the world’s

population live in MDCs, but they consume about 80 percent

of its mineral and energy resources. In contrast the LDCs

are poorer and less industrially-developed. They tend to be

located in the Southern Hemisphere where the

climate

is

919

less favorable and soils are generally less fertile. Though the

boundaries are purposely vague, this dichotomy is useful for

contrasting the economic and social welfare of the richer

and poorer countries and in critical environmental categories

involving mainly demographic, economic, and social

statis-

tics

. See also Environmental economics; First World; Third

World

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Ehrlich, P. R., and A. H. Ehrlich. “Growing, Growing, Gone (Rich Nations

Must Recognize Their Responsibility to Aid Overpopulated Third World).”

Sierra 75 (March-April 1990): 36–40.

Preston, S. H. “Population Growth and Economic Development.” Environ-

ment (March 1986): 6–9+.

Mortality

A measure of the death rate in a biological population,

usually presented in terms of the number of deaths per

hundred or per thousand. If there are 100 mice at the begin-

ning of the year and fifteen of them die by the end of the

year, the group’s mortality rate is fifteen per 100 individuals

(the initial population), or 15 percent. In ecological and

demographic studies of populations mortality is an important

measurement, along with birth rates (natality), immigration,

and emigration, used to assess changes in population size

over time. In human populations mortality rates are often

figured for specific age and gender groups, or for other

population categories including race, income level, occupa-

tion, and so on. This way group mortality rates can be

compared and risks for each subgroup can be evaluated. See

also Evolution; Extinction; Population growth; Zero popula-

tion growth

Mount Pinatubo

Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted on June 15,

1991. When the 5,770-ft (1760 m) mountain shot

sulfur

dioxide

25 mi (40 km) into the

atmosphere

, the cloud

mixed with water vapor and circled the globe in 21 days,

temporarily offsetting the effects of global warming. Satellite

images taken of the area after the eruption showed a dustlike

smudge in the

stratosphere

. The sulfur dioxide cloud de-

flected 2% of the earth’s incoming sunlight and lowered

temperatures on worldwide average. Although the effects

on global temperatures were significant, they are thought to

be temporary. These light sulfur dioxides are expected to

remain in the stratosphere for years and contribute to damage

to the

ozone

layer.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mount St. Helens

The Philippine islands originated as volcanoes built

up from the ocean floor. Most volcanoes erupt along plate

edges where ocean floors plunge under continents and melt-

ing rock rises to the surface as magma. The earth’s crust

pulls apart, creating gaps where the magma can rise. The

island of Luzon, where Mount Pinatubo is located, has

thirteen active volcanoes. The pattern of volcanoes around

the rim of the Pacific Ocean is called the Ring of Fire.

Mount Pinatubo sits in the center of a 3-mi (5-km)

wide caldera, a depression from an earlier eruption that made

the

volcano

collapse in on itself. A new cone formed over

time, and geothermal vents gave a clue that the volcano

was active. Before the 1991 eruption, Mount Pinatubo last

erupted 600 years ago. In April 1991 steam eruptions, earth-

quakes, increasing sulfur dioxide emissions, and rapid growth

of a lava dome all indicated a powerful impending blast.

Minor explosions began on the mountain on June 12, 1991.

This major eruption occurred in a country with an

already shaky economy, and the human effects are likely to

be significant for a long period of time. A total of 42,000

homes and 100,000 acres (40,500 ha) of crops were de-

stroyed. Nine hundred people died and 200,000 were relo-

cated, with 20,000 people remaining in tent cities. More

than 500 of those have died from disease and exposure.

The country suffered over $1 billion in economic losses.

Nevertheless, many lives were saved as a consequence of

scientists’ predictions of the eruption.

The destruction from Mount Pinatubo came mostly

from lahars, rushs of cementlike mud, formed when heavy

rains loosened the tons of ash dumped on the mountain’s

sides. These lahars can bury towns and roads and virtually

anything else in the way. Also deadly were the pyroclastic

flows, killer clouds of hot gases, pumice, and ash that traveled

up to 80 mi (130 km) per hour across the countryside, up

to 11 mi (18 km) away from the volcano. See also Geothermal

energy; Greenhouse effect; Ozone layer depletion; Plate tec-

tonics

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Berreby, D. “Acid-Flecked Candy-Colored Sunscreen.” Discover 13 (Janu-

ary 1992): 44–46.

Brasseur, G. “Mount Pinatubo Aerosols, Chlorofluorocarbons, and Ozone

Depletion.” Science 257 (28 August 1992): 1239–42.

Grove, N. “Volcanoes: Crucibles of Creation.” National Geographic 182

(December 1992): 5–41.

Kerr, R. A. “Pinatubo Global Cooling on Target.” Science 259 (January 29,

1993): 594.

Monastersky, R. “Pinatubo Deepens the Antarctic Ozone Hole.” Science

News 142 (October 24, 1992): 278–79.

920

Mount St. Helens

On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens exploded with a force

comparable to 500 Hiroshima-sized atom bombs. David

Johnston, a United States

Geological Survey

(USGS) geol-

ogist based at a monitoring station six miles (9.7 km) away

announced the eruption with his final words, “Vancouver,

Vancouver, this is it.” Dramatic photograph’s provided the

public with an awesome display of nature’s power.

Mount St. Helens, in southwestern Washington near

Portland, Oregon, is part of the Cascade Range, a chain

of subduction volcanoes running from northern California

through Washington. The Mount St. Helens eruption was

instrumental in the expansion of the USGS

Volcano

Haz-

ards Program. Research at the new Cascades Volcano Obser-

vatory in Vancouver, Washington, has strengthened basic

understanding of volcanic processes and the ability to predict

eruptions. Highly relevant ecological studies have corrected

previous errors and misconceptions, leading to a new theory

about nature’s ability to recover after such events.

Research has heightened public awareness of the in-

herent instability of high, snow-covered volcanoes, where

even small eruptions can almost instantaneously melt large

volumes of snow. A relatively small 1985 eruption at Nevado

del Ruiz in central Colombia killed more than 23,000 people.

The Mount St. Helens blast and subsequent collapse gener-

ated a 0.7 cubic mile (2.8 km

3

) mud flow which raced 22

miles (35 km) at speeds as high as 157 mph (253 kph).

This caused massive problems, even halting traffic on the

Columbia River. These flows may also create unstable

dams

,

which may burst years after the intial eruption.

In addition to its awesome power and destructive force,

the Mount St. Helens eruption has provided rich material

for research. Conductivity studies have located a large rotat-

ing block under Mounts Rainier, Adams, and St. Helens, the

friction from which is a likely source of eruptions. Geologic

mapping and historical research, coupled with field studies

of current volcanism, have corrected misconceptions and

given clues to hazard frequency. Studies of nature’s recovery

efforts have produced surprises, notably the early arrival in

the eruption zone of predatory insects; elk grazing in open,

reforested areas; and the explosive growth of uncommon,

dangerous bacteria due to the high temperatures generated

by the eruption. Biological legacy has emerged as the unifying

theory describing nature’s recovery capabilities, an idea with

direct applications to forestry practices and

reclamation

of human-disturbed land. Nature’s mess provides valuable

nutrients and nurseries; furthermore, old growth areas within

managed ecosystems nurture the recovery of

biodiversity

.

Mount St. Helens has provided a unique laboratory

for study of volcano hazards and nature’s ability to recover

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

John Muir

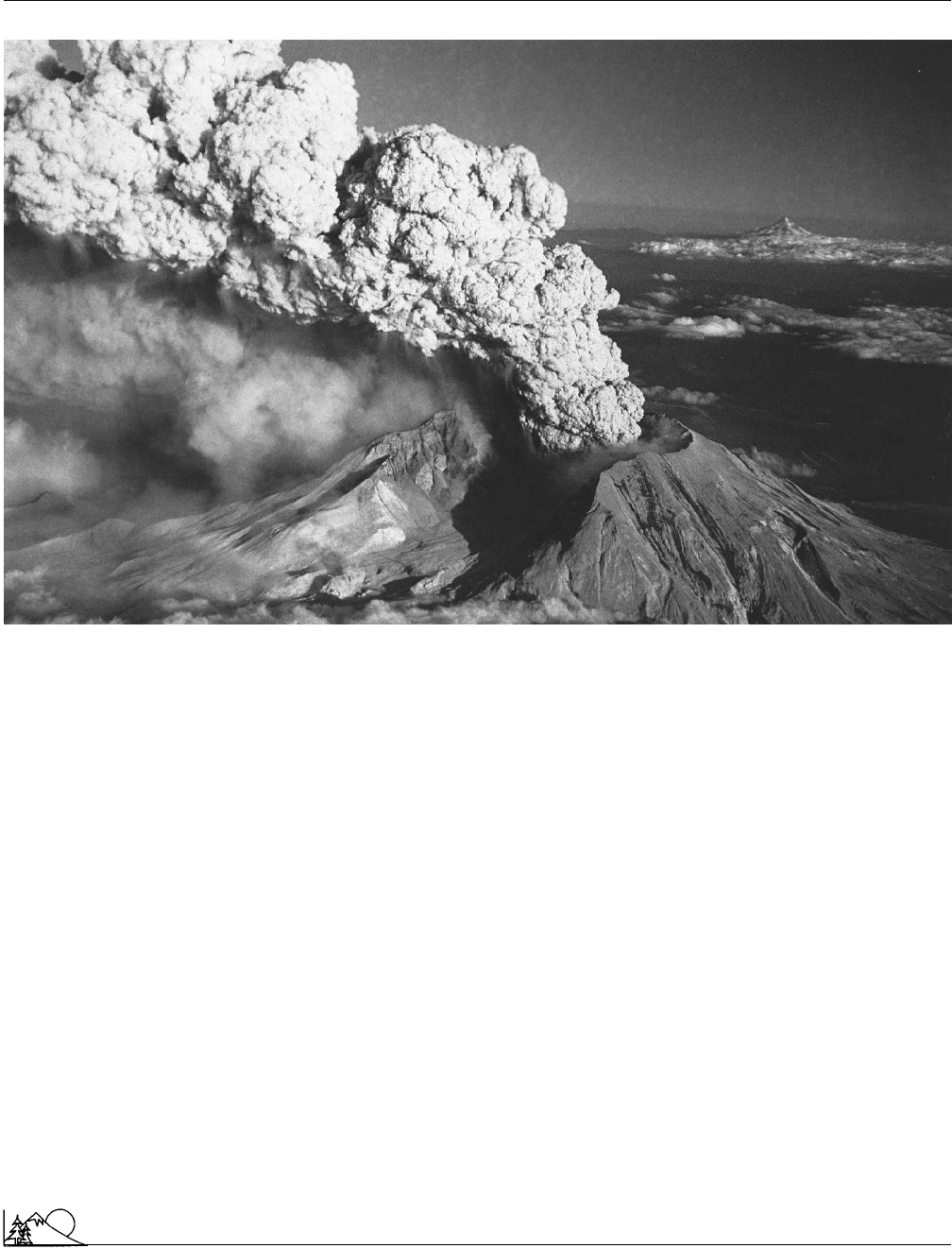

Mount St. Helens erupting with Mt. Hood in the background. (UPI/Corbis-Bettmann Newsphotos. Reproduced by permission.)

from the devastation caused by volcanic eruptions. See also

Mount Pinatubo, Philippines; Reclamation; Topography

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bilderback, D. E., ed. Mount St. Helens, 1980: Botanical Consequences of

the Explosive Eruptions. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

Decker, R., and B. Decker. “Eruption of Mount St. Helens.” Scientific

American 244 (March 1981): 68–80.

O

THER

Tilling, R. I., L. J. Topinka, and D. A. Swanson. Eruptions of Mount

St. Helens: Past, Present, and Future. USGS General Interest Publication.

Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1990.

Wright, T. L., and T. C. Pierson. Living With Volcanoes: The USGS Volcano

Hazards Program. USGS Circular 1073. Washington, DC: U. S. Govern-

ment Printing Office, 1992.

MTBE

see

Methyl tertiary butyl ether

921

John Muir (1838 – 1914)

American naturalist and writer

John Muir is considered one of the towering giants of the

conservation/environmental movement in the United States.

Anyone seriously interested in natural history,

conserva-

tion

,

wilderness

preservation, or the national parks in this

country should be aware of John Muir’s work. He was a

spirited, joyous naturalist, a serious student of glaciers, an

influential advocate of wilderness preservation, and the ac-

knowledged founder of the

national park

idea. Born in

Dunbar, Scotland, Muir emigrated with his family to the

United States in 1849 when he was 11 years old. He spent

his youth working on a farm in the Wisconsin wilderness,

trying to please his father, who was a deeply religious man.

The wilderness, his religious background, and the hard labor

influenced his thinking the rest of his life.

Muir’s father believed the Bible to be the only book

necessary for a young person, but Muir managed to educate

himself and to spend several years at the University of Wis-

consin (where he chose his own curriculum and so left with-

out a degree). After school, he worked at various jobs, gener-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

John Muir

ally quite successfully, until a factory accident temporarily

blinded him. He vowed that if his sight returned, he would

leave the factory and see as much of the world as possible.

After about a month, his sight did return and he left for

various jaunts in the wilderness, including a famous 1,000-

mi (1,609 km) walk through the country to the Gulf of

Mexico, an account recorded in A Thousand Mile Walk to

the Gulf (1916).

His eventual goal was to reach South America and

wander through the Amazonian tropical rain forests. He

reached Cuba, but a bout with fever (carried over from the

humid lowlands of Florida) turned him instead toward the

drier West, especially California and the Yosemite Valley,

about which he had seen a brochure and which he deter-

mined to see for himself. “Seeing for himself” also became

a life-time habit, and he eventually traveled over much of

the world. As he had planned, he did make it up the Amazon,

in 1911, at the age of 73.

Arriving in California in 1868, he made his way to

Yosemite and spent several years studying its landforms,

wildlife

, and waterways, earning his living by herding sheep,

working in a sawmill, and other odd jobs. As Edward Hoag-

land noted, Muir “lived to hike,” a mode of

transportation

that involved him intimately in the landscape. He traveled

light, and alone, often with little more than some dry bread

in a sack, tea in a pocket, a few matches and a tin cup, and

perhaps a plant press.

Through his travels in Yosemite, he became convinced

that the spectacular land forms of Yosemite had been carved

by glaciers or, as he put it, “nature chose for a tool...the

tender snow-flowers noiselessly falling through unnumbered

centuries.” His belief in glacial origins placed him in conflict

with the established scientific ideas of the time, especially

those held by the California state geologist. But Muir even-

tually prevailed, his ideas vindicated when he found the first

known glacier in the Sierra range. The results of his years

of intense glacial investigations are available in Studies in

the Sierra (1950). Current views have verified his theories,

changing only the number of glacial events and emphasizing

the role of water in cutting the canyons. Muir also made

five trips to Alaska to study glaciers there, one of which is

named for him.

His glacial studies were the principle contributions

Muir made as an original scientist, most of his life being

devoted to travel, writing, and conservation activism. Even

as early as 1868, Muir was concerned with the effects sheeph-

erding had on plant life and

soil erosion

.

Muir’s travels were interrupted for a time when, in

early 1880, he married Louise Strentzel, the daughter of a

fruit rancher in the Alhambra valley. Muir helped run the

ranch, first rented and then bought some of the acreage,

applying his inventiveness and hard work to fruit growing.

922

Reportedly, he was a good businessman, prospering after

only a decade to ensure a measure of financial independence.

He then sold part of the ranch and leased the rest, which

allowed him time with his daughters, to return to his beloved

wilderness, and to write and actively promote his wilderness

ideas. Muir’s intimate acquaintance with the Yosemite area

and the Sierra Nevada exposed him not only to the depreda-

tions of sheep but also to the rapid felling of giant old

Sequoias, cut up for shingles and grape stakes. Muir’s re-

sponse: “As well sell the rain clouds, and the snow, and the

river, to be cut up and carried away....” In 1889, he escorted

the editor of Century magazine to Yosemite and showed

him the negative impacts of sheep, which he called “hoofed

locusts.” A series of articles in that magazine alerted the

public to the destruction of the land, and they eventually

pressured Congress to establish the Yosemite area a national

park in 1890.

An earlier attempt to rally interest in the plight of the

western forests—a suggestion for a government commission

to survey the forests and recommend conservation mea-

sures—was also realized with the appointment of such a

commission in 1896. Charles Sargent, the chair of the com-

mission, invited Muir to participate and, on the basis of the

Sargent Commission’s recommendation, President Grover

Cleveland created thirteen forest preserves, setting aside 21

million acres. Negative reaction from commercial interests,

however, nullified most of these gains. Muir responded by

writing two articles on forest reserves and parks in Harper’s

Weekly and Atlantic Monthly in 1897. These articles helped

to rally public support and in 1898, the annulments were

reversed by Congress.

Muir influenced the public and extended his influence

by friendships and correspondence with some of the most

powerful people of his time. A number of the successes

of the early conservation movement, for example, can be

attributed to his influence on such figures as

Theodore

Roosevelt

. After a three-day camping trip with Muir under

the Big Trees in 1903, Roosevelt added many millions more

acres to the

national forest

system, as well as national

monuments and national parks and created what became

the

national wildlife refuge

system.

Known for his many successes, Muir was much sad-

dened by his one big loss: the damming of Hetch Hetchy

valley in

Yosemite National Park

as a

reservoir

to supply

water to San Francisco. Muir’s public image was damaged

by the excessive vehemence of his attacks upon the citizens

of San Francisco, whom he denounced as “satanic,” and

following the Hetch Hetchy incident, Muir retired to his

ranch to edit his journals for publication.

Muir never considered himself much of a writer and

begrudged the time it took away from his beloved mountains

and forests. Most of his books were published late in life,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act (1960)

John Muir and his dog. (Corbis-Bettmann. Repro-

duced by permission.)

after the turn of the century. His writings are still widely

read today by students, scholars, activists, and philosophers.

In the opinion of most observers, the primary importance

of Muir’s writings lies not in their literary quality but in the

fact that they persuaded a large number of Americans to

regard scenic wilderness areas as irreplaceable

natural re-

sources

which must be protected and preserved.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Browning, P., ed. John Muir in His Own Words: A Book of Quotations.

Lafayette, CA: Great West Books, 1988.

Cohen, M. P. The Pathless Way: John Muir and the American Wilderness.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Fox, S. John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Turner, F. Rediscovering America: John Muir in His Time and Ours. New

York: Viking Penguin, 1985.

P

ERIODICALS

Hoagland, E. “In Praise of John Muir.” Anteus no. 52 (Spring 1984): 170–83.

Wadden, K. A. “John Muir and the Community of Nature.” The Pacific

Historian 19 (Summer–Fall 1985): 94–102.

923

Mulch

Material applied to the surface of a

soil

to protect the soil

or to improve the

environment

of the soil’s surface. Mulch

can be made from many different kinds of organic or inor-

ganic materials like stones, bark, compost, leaves, wood

chips, and manure. The benefits of using mulch include

the following: protection of soil from

erosion

, evaporation

reduction, increased water

infiltration

, reduction in weed

seed germination, increased seed germination, and reduction

of

compaction

of soil. See also Animal waste; Composting;

Fertilizer; Soil organic matter; Soil texture; Topsoil

Multiple chemical sensitivity

Regarded by skeptics as a manifestation of “technophobia”

and “chemophobia,” multiple chemical sensitivity is a highly

controversial disorder associated with low levels of environ-

mental

chemicals

in general and volatile organic chemicals

in particular. Sufferers experience fatigue, malaise, headache,

dizziness, lack of concentration, and loss of memory, and

are often so disabled that they cannot live or work except

in completely chemical-free environments. Critics argue that

this condition should not receive clinical recognition as a

disease, insisting that the condition has no uniform cause

or consistent, measurable features. Advocates for sufferers

say it is a chronic condition marked by heightened sensitivity

to even slight chemical exposures; and that multiple symp-

toms occur in multiple organ systems, usually caused by large

“triggering” exposures such as to new carpeting that emits

chemicals.

Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act

(1960)

On June 12, 1960, Congress passed the Multiple Use-Sus-

tained Yield Act, designed to prevent the obliteration of

national forests by

logging

and

water reclamation

proj-

ects. This law officially mandated the management of na-

tional forests to “best meet the needs of the American peo-

ple.” The forests were to be used not primarily for economic

gain, but for a balanced combination of “outdoor

recreation

,

range, timber,

watershed

, and

wildlife

and fish purposes.”

The Multiple Use Act emerged from a strong history

of diverse uses of the federal reserves. Early settlers assumed

access to and free use of public lands. The text of the Sundry

Civil Act of 1897 mandated that no public forest reservation

was to be established except to improve and protect forests

and water flow. The act also provided for free use of timber

and stone and of all reservation waters by miners and resi-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Multi-species management

dents. The Act of February 28, 1899, strengthened use policy

by providing for recreational use of the reserves.

When the reserves were transferred from the General

Land Office to the Bureau of Forestry, the Secretary of

Agriculture signed a letter (actually written by

Gifford Pin-

chot

) dictating formal forest policy: “all the resources of the

forest reserves are for use... you will see to it that the water,

wood, and forage of the reserves are conserved and wisely

used.” The first and subsequent editions of the Use Book—

an extensive guide to management and use of

national

forest

lands—stated concisely that the aim of

Forest Service

policy was that “the timber, water, pasture, mineral and other

resources of the forest reserves are for the use of the people.”

The first use of the term “multiple use” appears to be

in two Forest Service reports of 1933. That year’s chief’s

report reaffirmed that the “principle to govern the use of

land...is multiple-purpose use.” The “National Plan for

American Forestry” (the Copeland Report) emphasized that

“the peculiar and highly important multiple use characteris-

tics of forest land [involve] five major uses--timber produc-

tion, watershed protection, recreation, production of forage,

and

conservation

of wildlife.”

Multiple use has always been controversial. Some crit-

ics argued that multiple uses meant that the Forest Service

was losing sight of its original protective function: a 1927

article in the Outlook claimed that “the Forest Service will

have to be called from its enthusiasm for entertaining visitors

to the original but more somber work of forestry.” Many

similar statements can be identified. A writer in the Journal

of Forestry in 1946 went so far as to propose separating all

the lands in each use class, consolidating each type into a

separate bureau under one cabinet officer. The

Sierra Club

proposed a vast land exchange in 1959, hoping to move

scenic areas out of the Forest Service and into the

U.S.

Department of the Interior

.

Critics have argued, and feel that subsequent policy

and events on the ground bear them out, that the Multiple

Use Act did not reduce confusion because it did not eliminate

water and timber as priority uses. Proponents of the act feel

that it did give statutory authority to all uses as equal to

timber and did give the other four uses more stature and

visibility

. See also Bureau of Land Management; Commer-

cial fishing; Public Lands Council

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bowes, M. D., and J. V. Krutilla. Multiple-Use Management: The Economics

of Public Forestlands. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 1989.

Frederick, K. D., and R. A. Sedjo, eds. America’s Renewable Resources:

Historical Trends and Current Challenges. Washington, DC: Resources for

the Future, 1991.

924

Steen, H. K. “Multiple Use: The Greatest Good of the Greatest Number”

and “Multiple Use Tested: An Environmental Epilogue.” In The United

States Forest Service: A History. Seattle, WA: University of Washington

Press, 1976.

Multi-species management

Multi-species management (MSM) specifies the develop-

ment of a particular ecologically balanced assessment and

operation in protecting fish and

wildlife

. Such protection

of

species

and the

environment

that supports and sustains

them relies on understanding the species’ interaction with

each other, and within a particular environment—whether

a body of water, a marshland, or other natural surroundings.

The

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) and the

U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

(FWS) play key roles in

overseeing this management due to the imperative for restor-

ing and maintaining an effective

ecosystem

. In concert with

the Endangerd Species Act (ESA), the focus in MSM is

on lessening the possibility of certain species being added

to the Endangered Species list in addition to the management

of those species currently thriving.

In the fall of 2002, the College of Foresty at Oregon

State University was hosting a symposium, Innovations in

Species Conservation for the purpose of studying the issues

of strategies for conserving species, ecological risks and un-

certainties associated with certain strategies, and examining

social and legal contexts of

conservation

strategies. The

announcement for the symposium pointed out that, “In the

past, efforts to conserve species have focused on providing

appropriate

habitat

for, and population management of,

individual high-profile species protected by laws and regula-

tions. Some regional plans have been designed to conserve

a broad array of species and biological diversity by specifying

protection of rare and uncommon species.” But according

to the research indicated, there also remain some questions

regarding the multi-species direction. The discussion goes

on to say that, “Such approaches have proven to be complex

and expensive, and have placed constraints on the ability

to meet other important management objectives. Multiple-

species or ecosystem approaches addressing species assem-

blages at regional scales may be more efficient and lessen

management constraints, but the degree to which they pro-

tect individual species rests more on hypothesis than on

systematic testing. Such multi-system approaches may also

be more susceptible to legal challenges due to a lower level

of certainty regarding the outcomes for a particular species.”

Still, by 2002, evidence continues to emerge from ex-

tensive research over the last few decades, that MSM has

produced some results that indicate success. The theory is

that if one species, or aspect of an ecosystem is out of balance,

therefore the entire system is out of balance. In a 1999 article

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Municipal solid waste

written by Dick Monroe, Vice President of Environmental

Affairs for Darden Restaurants, he noted that global man-

agement of

whales

and

seals

directly affected the seafood

and restaurant industry. It was his concern—in opposition

to the philosophy of many

animal rights

and whale watch

groups—that whales were consuming between three and six

times the total annual catch of all commercial fisheries. He

noted that an MSM approach must be supported because

when the focus is simply on one species, another is sure to

lose out and the supply depleted.

The Kyoto Treaty—the United States backed out of

support of the treaty under the George W. Bush administra-

tion in 2001—also specifies MSM as one of its components.

Throughout the United States, under the sponsorship of

various government and private agencies, MSM had become

an important research approach to environmental concerns.

It represents a worldwide effort as well as one for the United

States—especially in countries that rely heavily on the fishing

industry as a support of their economic system. In Norway,

for instance, in order to manage certain fishing stocks in the

Barents Sea, it was crucial for researchers to determine how

much of that species waaas eaten by another fish. The Insti-

tute of Marine Research in Bergen (Norway) developed a

multi-species model to address this issue, among others. In

managing the stock of capelin, it was crucial to know how

much of it was consumed by the cod, and also in marine

mammals. Beginning in 1987, Norwegian and Russian sci-

entists cooperated in collecting this information. By 1993,

the groups had collected samples from the stomach content

of over 50,000 cod. This example of the mechanism by which

MSM operates is typical of similar programs throughout the

United States, and around the world.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Gutting, Richard. “Action Needed to Avert Supply/Demand Gap.” Seafood

Industry (August 1996): 43.

Russell, Dick. “Hitting Bottom.&rdquo Amicus Journal February 3, 1997

[cited July 2002].

Valles, Colleen. “Panel Passes Restrictions on West Coast Fishing to Protect

Depleted Species.” Associated Press/Environmental News Network [cited June

21, 2002]. <http://www.enn.com/news>.

O

THER

Cardin, Ben. Testimony in Support of the Reauthorization of the Chesapeake

Bay Office of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration HR 4789.

September 21, 2000 [cited July 2002]. <http://www.house.gov/ca>.

Chesapeake Bay Program. Chesapeake 2000 Agreement. [cited June 2002].

<http://www.chesapeake.org>.

Chesapeake Bay Program. Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee. [cited

June 2002]. <http://www.chesapeake.org/stac>.

Food and Agriculture Organization. Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to

Food Security. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.fao.org/fi>.

925

IWMC (formerly International Wildlife Management Consortium). Envi-

ronment; What Do Whales have to do with Your Menu? September 25, 1999

[cited July 2002]. <http://www.iwmc.org>.

Norwegian-scenery. Norwegian Management of Marine Resources. [cited June

2002]. <http://www.norwegian-sceneery.com>.

Oregon State University, College of Forestry. Innovations in Species Conser-

vation. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.outreach.cof.orst.edu>.

Stefansson, Gunnar. “Management in the Multi-species Context.” Hafran-

nsoknastofnunin (Marine Research Institute). February 28, 2002 [July 2002].

<http://www.hafro.is>.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. National Fish Hatchery System. [cited June

2002]. <http://www.fisheries.fws.gov>.

White, Ph.D., Michael D. The Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conser-

vation Program. [cited June 2002]. <http://www.sci.sdsu.edu/salton>.

World Wildlife Fund. The Food-Web Effect. [cited June 2002]. <http://

www.panda.org/resources>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.,

Washington, D.C. USA 20460 202-260-2090, www.epa.gov

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. USA, www.fws.gov

Municipal solid waste

Americans generate about 160 million tons of municipal

solid waste

(MSW) per year not counting construction

debris. That’s enough

garbage

to fill a convoy of trash

trucks reaching half way from the earth to the moon. That

much garbage equals about 1,300 pounds (590 kg) of waste

per year for every person in the United States, or about 25

pounds (11.5 kg) per person per week. The

Environmental

Protection Agency

(EPA) tells us that every year Americans

throw away 60 billion cans, 28 million bottles, 4 million

tons of plastic, 40 million tons of paper, 100 million tires,

and 3 million cars. If growth in disposal rates continue,

Americans may generate nearly 2,000 million tons of MSW

by the year 2000.

Municipal solid waste is waste generated by house-

holds, commercial businesses, institutions, light industry and

agricultural enterprises and nontoxic wastes from hospitals

and laboratories. Municipal waste is composed of (in order

of volume contribution) paper/packaging,

yard waste

,

food

waste

, magazines/newspapers,

plastics

, glass, wood/fabric,

disposable diapers

, and other contributions such as tires,

appliances, and nontoxic home maintenance supplies. In

addition to this relatively benign list, there is other municipal

waste that ends up in a

landfill

inappropriately—e.g., left-

over paint, crankcase oil, batteries, and parts of some appli-

ances such as capacitors in refrigerators and air conditioners.

In some cases sewage

sludge

from the local

wastewater

treatment facility ends up in the landfill with other municipal

solid waste. It is these inappropriate wastes that cause con-

cern in the minds of local officials as they ponder the siting

of landfills.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Municipal solid waste composting

Since municipal waste is a non-homogeneous stream

of materials, its impact is unpredictable. Although only about

two percent of the municipal

waste stream

is toxic, even

that small amount has the potential of contaminating large

amounts of

groundwater

if the leachate from landfills reach

the

aquifer

. In addition, landfills situated near a lake or a

stream can leak laterally and contaminate surface water. In

spite of the fact that the engineering of landfills has become

much more sophisticated in the last 10 years, there is still

sincere concern about the impact of municipal waste on

ground and surface water.

Several methods for managing municipal solid waste

have been designed and implemented over the last 20 years.

In the United States, 80% or more of the municipal solid

waste ends up in landfills, about 10% is incinerated, and

about 11% is recycled. Waste-to-energy

incineration

is an

option aimed at reducing the volume of municipal waste

and producing an ongoing supply of energy for nearby mar-

kets. The complication of this treatment method is the ash

residue and its disposal as well as

air pollution

. Probably

the most desirable management technique for MSW is

re-

cycling

.

Recycling captures the embodied energy in the prod-

ucts to be discarded. The conversion of the waste stream

into a second or third generation of usable products is far

superior to simple volume destruction or land burial. Unfor-

tunately, recycling requires behavioral change on the part of

the waste generator and behavioral and infrastructure change

on the part of industry in order to create markets for post

consumer materials. Individuals must learn to clean and

separate household garbage and make it ready for recycling.

Industry must make the investment to change manufacturing

processes to accommodate a heterogeneous “raw” material.

Even more desirable than recycling is source reduction

and

reuse

of household products and industrial and business

supplies. Buying durable and re-usable products reduces the

volume of the MSW stream. Packaging that can be reused

after the product has been used is another way of shrinking

municipal solid waste volume. In some European countries

like Germany, manufacturers are required to take back all

their packaging materials.

The cost of MSW disposal has increased dramatically

over the last 10 years. Part of this cost is due to the pressure

being put on fewer and fewer landfills as older landfills close.

Many metropolitan areas of the United States have exhausted

their landfill capacity and are transporting waste into rural

areas. Unfortunately, in rural areas the volume of MSW is

not sufficient for landfill companies to make the investment

and build state-of-the-art landfills. Furthermore there is

increasing concern that many towns and cities are dumping

their MSW in areas where people have less political power

or need the revenue from tipping fees. Consequently the

926

management of waste has become a social issue as well as

an environmental concern.

Currently there are approximately 3,500 licensed land-

fills operating in the United States. Tipping fees have in-

creased as have transport fees. States are transporting MSW

hundreds of miles to other states because they can’t build

landfills due to citizen opposition. The NIMBY (

Not In

My Backyard

) syndrome makes it difficult to create more

landfills.

Waste management

companies are offering ex-

tensive incentive packages to local communities in order to

get approval for landfill siting. Yet, almost without exception,

local citizens attempt to block the construction of landfills.

Municipal solid waste is a renewable resource. We will

always have new supplies of it. Even though many citizens

are beginning to turn to nondisposable items and there is a

real effort to launch recycling programs nationwide, we are

still faced with an increasing volume of municipal waste. It

is a complex problem that will require behavioral change on

the part of individuals, a commitment on the part of local

city planners, and an investment on the part of industry in

order to recycle the waste stream. See also Medical waste

[Cynthia Fridgen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Blumberg, L., and R. Gottlieb. War on Waste: Can America Win Its Battle

with Garbage? Washington, DC: Island Press, 1989.

Rathje, W., and C. Cullen. Rubbish! The Archaelogy of Garbage. New York:

Harper-Collins Publishers, 1992.

The Solid Waste Dilemma: An Agenda for Action. Washington, DC: Environ-

mental Protection Agency, 1989.

Municipal solid waste composting

Municipal Solid Waste

(MSW) composting is a rapidly

growing method of solid

waste management

in the United

States. MSW includes the residential, commercial, and insti-

tutional

solid waste

generated within a community. MSW

composting

is the process by which the organic,

biode-

gradable

portion of MSW is microbiologically degraded

under

aerobic

conditions.

During the process of degradation, bacteria are used

to decompose and break down the organic matter into water

and

carbon dioxide

, which produces large amounts of heat

and water vapor in the process. Given sufficient oxygen and

optimum temperatures, the composting process achieves a

high degree of volume reduction and also generates a stable