Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mutation

end product called compost that can be used for mulching,

soil

amendment, and soil enhancement. As a form of solid

waste management, MSW composting reduces the amount

of waste that would otherwise end up in landfills.

Although composting has been practiced by humans

for centuries, the concept of composting mixed solid waste

as a form of large-scale solid waste management is still in

an early stage of development in the United States. MSW

generally consists of a mixture of organic compostable mate-

rials such as

food waste

and paper and inert, nonbiodegrad-

able materials such as

plastics

and glass. The introduction of

non-compostable materials may pose problems in materials

handling during the composting process and also hinder the

formation of a uniform, homogeneous compost. Therefore,

in order to practice MSW composting as a form of waste

management, the composting system must be designed to

remove the non-compostable materials either by presorting

and screening or by sifting and removal at the end of the

process.

The three most common methods of MSW compost-

ing are closed in-vessel, windrow, and static aerated pile

composting. The method of choice depends on the volume

of waste to be composted and the availability of space for

composting. In the closed in-vessel method, the MSW is

physically contained within large drums or cylinders and all

necessary

aeration

and agitation is supplied to the vessel.

In windrows, the MSW is heaped in long rows of material

approximately four to seven feet high. Air and ventilation are

supplied by physically turning over the piles with mechanical

windrow turners. In static aerated compost piles, the MSW

piles are not physically agitated, rather air is supplied and

excess heat is removed by a system of sensors and pipes

within the pile. In all cases, the goal is to ensure a steady,

optimum rate of composting by providing adequate oxygen

and ventilation to remove excess heat and water so that

microbiological action is not impaired. When there is insuffi-

cient air supply, microbial action is unable to fully decompose

the waste and the piles become

anaerobic

and unpleasant

odors and putrefaction may result. Strong neighborhood

complaints against odors is the single most common reason

for the failure and shutdown of composting plants.

In the United States, numerous, small-scale, pilot proj-

ects have demonstrated the feasibility of MSW composting

for townships and municipalities. However, there are rela-

tively few operations that successfully carry out MSW com-

posting on a large, commercial scale. The operational large-

scale facilities are located mainly in Florida and Minnesota,

two states that have traditionally shown interest in innovative

waste management options. See also Aerobic sludge diges-

tion; Solid waste incineration; Solid waste recycling and

recovery; Waste reduction

[Usha Vedagiri]

927

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Goldstein, N., and R. Steuteville. “Solid Waste Composting in the United

States.” Biocycle 33 (1992): 44–52.

Mustela nigripes

see

Black-footed ferret

Mutagen

Any agent, chemical or physical, that has the potential for

inducing permanent change to the genetic material of an

organism by altering its DNA. The alteration may be either

a point

mutation

(nucleotide substitution, insertion, or dele-

tion) or a chromosome aberration (translocation, inversion,

or altered chromosome complement). There are long lists

of chemical mutagens which include such diverse agents

as formaldehyde, mustard gas, triethylenemelamine,

vinyl

chloride

,

aflatoxin

B, benzo(a)pyrene, and acridine orange.

Chemical mutagens may be direct acting, or they may have to

be converted by metabolic activity to the ultimate mutagen.

Physical mutagens include (but are not limited to) x rays

and

ultraviolet radiation

. See also Agent Orange; Birth

defects; Chemicals; Gene pool; Genetic engineering; Love

Canal, New York

Mutation

A mutation is a change in the DNA of an organism, which

is genetically transmitted, and may give rise to a heritable

variation. Mutagens, substances that have the competence

to produce a mutation, may be subject to chromosomal

changes such as deletions, translocations, or inversions. Mu-

tations may also be more subtle, resulting in changes of only

one or a few nucleotides in the sequence of DNA. These

more subtle mutations are called as “point mutations,” and it

is these that most people refer to when discussing mutation.

Ordinarily, mutation is thought of as a genetic change

that results in alterations in a subsequent generation. Germi-

nal tissue, which gives rise to spermatozoa and ova, is the

tissue in which such mutations occur. However, mutations

can arise in many cell types in addition to the germ line,

and these changes to non-germinal DNA are referred to

as somatic mutations. Although somatic mutations are not

passed to subsequent generations, they are not less important

than germinal mutations.

Ionizing radiation

and certain

chemicals

can have mutagenic effects on somatic cells which

often result in

cancer

.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mutualism

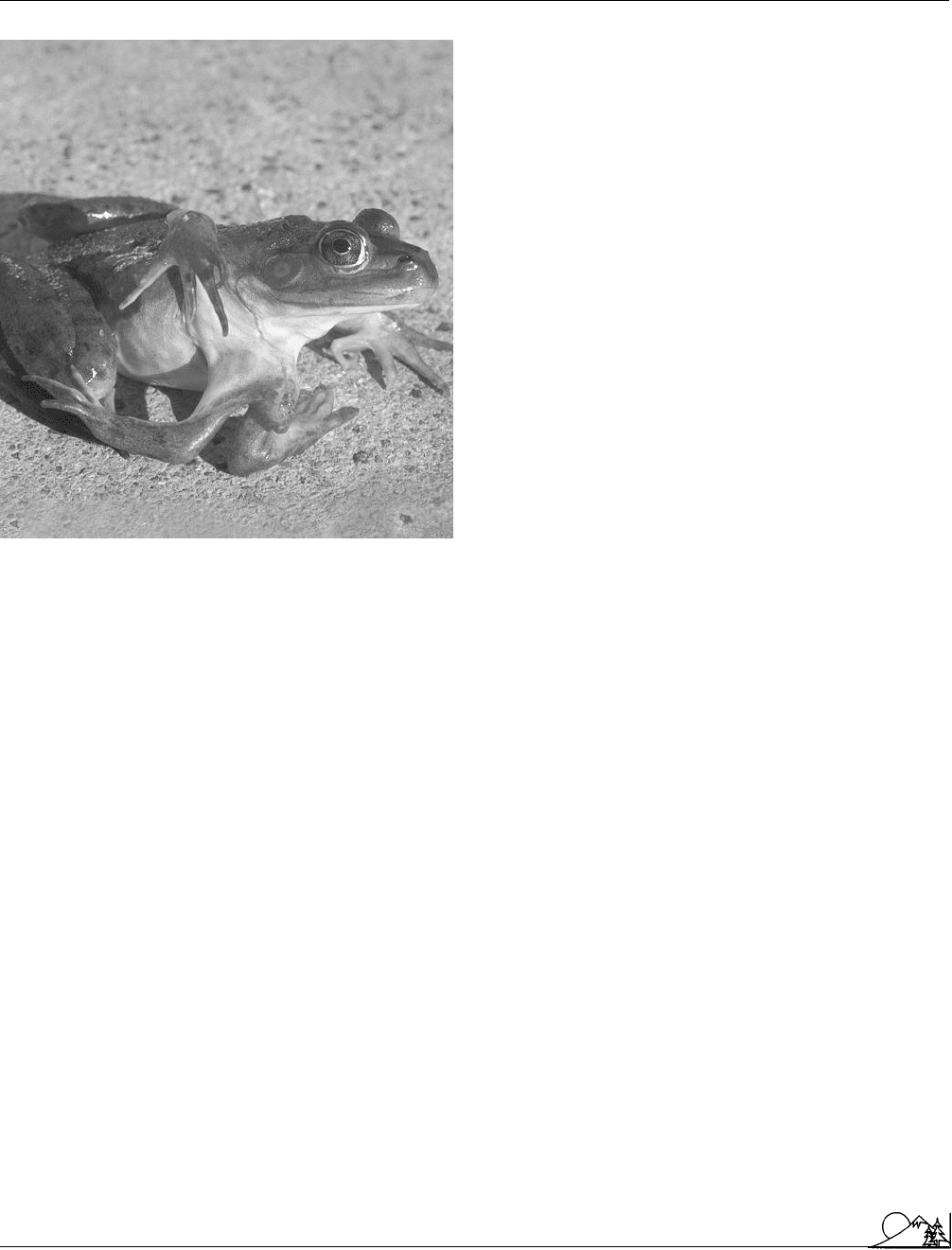

A six-legged green frog— the result of a genetic

mutation. (JLM Visuals. Reproduced by permission.)

Mutations may be either spontaneous or induced. The

term spontaneous is perhaps misleading; even these muta-

tions have a physical basis in cosmic rays, natural

back-

ground radiation

, or simply kinetic effects of molecular

motion. Induced mutations ensue from known exposure to

a diversity of chemicals and certain ionizing radiations.

DNA is composed of a linear array of nucleotides,

which are translocated through RNA into protein. The ge-

netic code consists of consecutive nucleotide triplets which

correspond to particular amino acids, and it may be altered by

substitution, insertion, or deletion of individual nucleotides.

Substitution of a nucleotide in some cases can be inconse-

quential, since the substituted nucleotide may specify an

amino

acid

which does not affect the function of the protein.

On the other hand, substitution of one nucleotide for another

one can result in a protein gene product with a changed

amino acid sequence that has a major biological effect. An

example of such a single nucleotide substitution is sickle cell

hemoglobin, which differs from normal hemoglobin by a

single amino acid. The substitution of a valine for a glutamic

acid in the mutant hemoglobin molecule results in sickle

cell disease, which is characterized by chronic hemolytic

anemia

.

The insertion or deletion of a single nucleotide pair

results in what is known as a frameshift mutation; this is

928

because the mutation changes the sequence of molecules

beyond the point at which it occurs, causing them to be

read in different groups of three. Consequently, there is a

miscoding of the nucleotides into their gene product. Such

proteins are usually shortened in length and no longer func-

tional.

[Robert G. McKinnell]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Mutagenic Effects of Environmental Contaminants. New York: Academic

Press, 1972.

Mutualism

A mutualism is a

symbiosis

where two or more

species

gain mutual benefit from their interactions, and suffer nega-

tive impacts when the mutualistic interactions are prevented

from occurring. Mutualism is a form of symbiosis where the

interactions are frequently obligatory, with neither species

being capable of surviving without the other. A well-known

example of mutualism is the relationship between certain

species of algae or blue-green bacteria and

fungi

that results

in organisms called

lichens

. The fungal member of the

relationship provides a spatial

habitat

for the algae, which

in turn provide energy from

photosynthesis

to the fungus.

Mutualistic interactions are thought to be the origin of the

many cell organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts,

which may have resulted from the acquisition of free-living

phytoplankton

and other single-celled organisms by host

species. Both the incorporated cell and the host soon evolved

so that neither could exist without the other.

[Marie H. Bundy]

MW

see

Megawatt

Mycorrhiza

Refers to a close, symbiotic relationship between a fungus

and the roots of a higher plant. Mycorrhiza (from the Greek

myketos meaning fungus and rhiza meaning root) are com-

mon among trees in temperate and tropical forests. There

are generally two forms—ectomycorrhiza, where the fungus

forms a sheath around the plant roots, and endomycorrhiza,

where the fungus penetrates into the cells of the plant roots.

In both cases, the fungus acts as extended roots for the plant

and therefore increase its total surface area. This allows for

greater

adsorption

of water and nutrients vital to growth.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mycotoxin

Mycorrhiza even allow plants to utilize nutrients bound up

in silicate minerals and phosphate-containing rocks that are

normally unavailable to plant roots. They also can stimulate

the plants to produce

chemicals

that hinder invading patho-

gens in the

soil

. In addition to the physical support, the

mycorrhiza obtain carbohydrates from the higher, photosyn-

thetic plant. This obligate relationship between

fungi

and

plant roots is especially important in nutrient-impoverished

soils. In fact, many trees will not grow without mycorrhiza.

See also Symbiosis; Temperate rain forest; Tropical rain forest

Mycotoxin

Mycotoxins are toxic biochemical substances produced by

fungi

. They are produced on grains, fishmeal, peanuts, and

many other substances, including all kinds of decaying vege-

tation. Mycotoxins are produced by several

species

of

929

fungi—especially Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium—

under appropriate environmental conditions of temperature,

moisture, and oxygen on crops in the field or in storage

bins. In recent years, research on this subject has indicated

considerable specialization in mycotoxin production by

fungi. For example, aflatoxins B

1

,B

2

,G

1

, and G

2

are rela-

tively similar mycotoxins produced by the fungus Aspergillus

flavus under conditions of temperatures ranging from 80-

100°F (27-38°C) and 18-20% moisture in the grain. Aflatox-

ins are among the most potent carcinogens among naturally

occurring products. Head scab on wheat in the field is pro-

duced by the fungus Fusarium graminearum which produces

a mycotoxin known as DON (deoxynivalenol), also known

as Vomitoxin.

Myriophyllum spicatum

see

Eurasian milfoil

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

N

NAAQS

see

National Ambient Air Quality

Standard

Ralph Nader (1934 – )

American consumer advocate

Born in Connecticut, Ralph Nader is the son of Lebanese

immigrants who emphasized citizenship and democracy and

stressed the importance of justice rather than power. Nader

earned his bachelor’s degree in government and economics

from Princeton University in 1955 and his law degree from

Harvard University in 1958, having served as editor of the

prestigious Harvard Law Record. Nader reads some 15 publi-

cations daily and speaks several languages, including Arabic,

Chinese, and Russian.

Nader published his first article, “American Cars: De-

signed for Death,” as editor of the Harvard Law Record.He

later made his reputation with Unsafe at Any Speed (1965),

a condemnation of the American

automobile

industry’s

record on safety. The book was initially commissioned by

then-assistant secretary of labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan

in 1963 as a report to congress, and was then brought out

as a trade book by a small publisher. In the book Nader

condemned U.S. automakers for valuing style over safety in

developing their products and specifically targeted General

Motors and its Chevrolet Corvair. General Motors hired a

private investigator to dig dirt on Nader, resulting in a scan-

dal that propelled the book to best-seller status. The contro-

versy that Unsafe at Any Speed generated led to passage of

the Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, which

gave the government the right to enact and regulate safety

standards for all automobiles sold in the United States.

With the money and fame generated by his book,

Nader went on to champion a wide variety of causes. He

played a key role in the establishment of the

Occupational

Safety and Health Administration

(OSHA) as well as the

Consumer Product Safety Commission. One of his most

931

important victories was the establishment of the

Environ-

mental Protection Agency

(EPA) in 1970, during the

Nixon administration. He also worked to ensure passage of

the Freedom of Information Act (1974). Nader got many

young people to work on consumer and environmental issues

through the Public Information Research Groups found on

college campuses across the country. To assist him in his

far-reaching investigative efforts, Nader created a watchdog

team, known as Nader’s Raiders. This group of lawyers was

the core of what became the Center for Study of Responsive

Law (CSRL), which has been Nader’s headquarters since

1968. A network of public interest organizations branched

off from CSRL, including Public Citizen, Health Research

Group, Critical Mass Energy Project, and Congress Watch.

Other groups have been established by Nader’s associates,

and though not run by Nader himself, they follow the same

ideals as CSRL and work toward similar goals. Among these

groups are: the Clean Water Action Project, the Center

for Auto Safety, and the

Center for Science in the Public

Interest

. A 1971 Harris poll placed Nader as the sixth most

popular figure in the nation, and he is still recognized as

the most important consumer advocate in the country.

Nader was at the height of his influence during the

1970s, but through the 1980s and early 1990s he was less

in the public eye. The Reagan years saw a loosening of the

regulations for which he had fought, and Nader himself

suffered many personal setbacks, including the death of his

brother and his own neurological illness. In 1987, Nader

vigorously campaigned for Proposition 103 in California,

which would roll back automobile insurance rates. The bill

passed and exit polls showed that Nader’s efforts had made

the difference. Though he had been asked to run for presi-

dent by the Beatles’ John Lennon and by writer Gore Vidal

in the early 1970s, Nader had always claimed that he needed

to stay outside government in order to reform it. This

changed in 1992, when Nader asked voters to write him in

on the presidential ballot. He voiced his disgust at the two

major parties, the Republicans and the Democrats, and asked

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Arne Naess

Ralph Nader. (AP/Wide World Photos. Reproduced

by permission.)

to be considered as a “none-of-the-above” option. In 1996

he made a wider effort as the candidate for the Green Party.

Nader was on the ballot in 21 states and polled a minus-

cule.68 percent of the vote (Reform Party candidate Ross

Perot by contrast earned over 8 percent of the total national

vote). Nader ran an informal campaign, mainly touring col-

lege campuses, and he did not appear to have much of an

effect on the election. In 2000 Nader ran a much more

concerted campaign, again as the Green Party candidate.

He famously declared the leading candidates, George W.

Bush and Al Gore to be “tweedledum and tweedledee,”

meaning they were virtually indistinguishable because of

their support for corporate interests. Late in the campaign, it

appeared that Gore and Bush were tied, and the Democratic

party began to excoriate Nader. Though it appeared that

Nader might siphon crucial votes away from Gore and thus

let Bush win, Nader refused to alter his position or throw

his support to Gore.

Environmentalism

became a key issue

in the three-way race. Though Gore had a strong record on

the

environment

and Bush what might be called an

abyssmal one, Nader continued to criticize Gore for not

having done enough. Finally, Gore won the popular vote

with 48.39%, Bush came in with 47.88%, and Nader with

2.72%. But the election went to Bush after the Supreme

Court halted the recount of contested Florida ballots, and

932

that state’s electoral college votes put Bush in the White

House. Nader had won some 97,000 votes in Florida, and

arguably if these votes had all gone to Gore, the outcome

of the presidential race would have been different.

After the election, Nader was anathemized in some

circles, and blamed for Gore’s loss. Nader claimed to have

no regrets except that he had not gotten at least 5% of the

vote, which would have qualified the Green Party for federal

matching funds for an election campaign in 2004. Nader

published a memoir about the campaign, called Crashing the

Party: How to Tell the Truth and Still Run for President.

He refused to speculate about whether he would run for

president again.

[Kimberley Peterson]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Alterman, Eric. “Left in Shambles.” Nation 271, no. 17 (November 27,

2000): 10.

Colapinto, John. “Ralph Nader Is Not Sorry.” Rolling Stone, September

13, 2001, 64–71.

Heilbrunn, Jacob. “Leftover.” Commentary 113, no. 3 (March 2002): 74.

Kennedy, Robert F. “Nader’s Threat to the Environment.” New York Times,

August 10, 2000, A21.

McLaughlin, Abraham. “Nader’s Voters: Steadfast...Or Switchable?” Chris-

tian Science Monitor (October 30, 2000): 2.

Dr. Arne Naess (1912 – )

Norwegian philosopher and naturalist

Arne Naess is a noted mountaineer and philosopher and the

founder of the

deep ecology

movement. He was born to

Ragnar and Christine Naess in Oslo, Norway, on January

27, 1912, the youngest of five children. Naess was an intro-

spective child, and he displayed an early interest in logic and

philosophy. After undergraduate work at the Sorbonne in

Paris, he did graduate work at the University of Vienna, the

University of California, Berkeley, and the University of

Oslo. While in Vienna, his interests in logic, language, and

methodology drew him to the Vienna Circle of logical em-

piricism. He was awarded the Ph.D. in philosophy from the

University of Oslo in 1938.

A year later, in 1939, Naess was made full professor of

philosophy at the same university. He promptly reorganized

Norwegian higher education, making the history of ideas a

prerequisite for all academic specializations and encouraging

greater conceptual sophistication and tolerance. From the

beginning, Naess was interested in empirical semantics, that

is, how ordinary persons use words to communicate. In

“Truth” as Conceived by Those Who Are Not Professional Philos-

ophers (1939), he was one of the first to use statistical methods

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Arne Naess

and questionnaires to survey philosophical beliefs. Shortly

after his appointment at the university, the Germans occu-

pied Norway. Naess resisted any changes in academic rou-

tine, insisting that education be separate from politics. The

increasing brutality of the Quisling regime, however, im-

pelled him to join the

resistance

movement. While in the

resistance he helped avert the shipment of thousands of

university students to concentration camps. Immediately

after the war, he confronted Nazi atrocities by mediating

conversations between the families of torture victims and

their pro-Nazi Norwegian victimizers.

In the post-War period, Naess’s academic interests

and accomplishments were many and varied. He continued

his work on language and communication in Interpretation

and Preciseness (1953) and Communication and Argument

(1966), concluding that communication is not based on a

precise and shared language. Rather we understand words,

sentences, and intentions by interpreting their meaning.

Language is thus a double-edged sword. Communication is

often difficult and requires successive interpretations. Even

so, the ambiguity of language allows for a tremendous flexi-

bility in verbal meaning and content. Because of his work

in communication and his resistance to the Nazis, Naess

was selected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] in 1949 to explore

the meanings of democracy. This project resulted in Democ-

racy, Ideology and Objectivity (1956). In 1958, he founded

the journal Inquiry, serving as its editor until 1976. The

magazine explores the relations of philosophy, science, and

society, especially as they reflect normative assumptions and

implications. He also published on diverse topics, including

Gandhian nonviolence, the philosophies of science, and the

Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677). These

works include Gandhi and the Nuclear Age (1965), Skepticism

(1968), Four Modern Philosophers: Carnap, Wittgenstein, Hei-

degger, Sartre (1968), The Pluralist and Possibilist Aspect of

the Scientific Enterprise (1972), and Freedom, Emotion and

Self-Subsistence: The Structure of a Central Part of Spinoza’s

“Ethic" (1972).

Naess began examining humanity’s relationship with

nature

during the early 1970s. The genesis of this interest

is best understood in the context of Norway’s

environment

,

culture, and politics. Nature, not humanity, dominates the

landscape of Norway. The nation has the lowest population

density in Europe, and over 90% of the land is undeveloped.

As a consequence, the interior of Norway is relatively wild

and diverse, a mixture of mountains, glaciers, fjords, forests,

tundra

, and small human settlements. Moreover, Norwe-

gian culture deeply values nature; environmental themes are

common in Norwegian literature, and the majority of Nor-

wegians share a passion for outdoor activities and

recre-

ation

. This passion is known as friluftsliv, meaning “open air

933

life.” Friluftsliv is widely touted as one means of reconnecting

with the natural world. Norwegian environmental politics

has been wracked by a

succession

of ecological and resource

conflicts. These conflicts involve

predator control

, recre-

ation areas, national parks, industrial

pollution

,

dams

and

hydroelectric power, nuclear energy, North Sea oil, and eco-

nomic development. During the 1960s Naess became deeply

involved in environmental activism. Indeed, his participation

in protests lead to his arrest for nonviolent civil disobedience.

He even wrote a manual to help environmental and commu-

nity activists participate in nonviolent resistance. Growing

up, Naess was deeply moved by his experiences in the wild

places of Norway. He became an avid mountaineer, leading

several ascents of the Tirich Mir (25,300 ft [7700 m]) in

the Hindu Kush range. In 1937, he built a small cabin near

the final assent to the summit of Hallingskarvet, a mountain

approximately 111 mi (180 km) northeast of Oslo. He named

it Tvergastein, meaning “across the stones.”

Since his retirement, Naess has published widely on

environmental topics. His main contributions are in ecophi-

losophy,

environmental policy

, and

conservation biol-

ogy

. The insight and controversy surrounding these writings

have propelled him to the forefront of

environmental ethics

and politics.

Naess regards philosophy as “wisdom in action.” He

notes that many policy decisions are “made in a state of

philosophical stupor” wherein narrow and short-term goals

are all that is considered or recommended. Lucid thinking

and clear communication help widen and lengthen the op-

tions available at any point in time. Naess describes this

work as a labor in “ecophilosophy,” that is, an inquiry where

philosophy is used to study the natural world and humanity’s

relationship to it. Recalling the ambiguity of language and

communication, he distinguishes ecophilosophy from ecoso-

phy—a personal philosophy whose conceptions guide one’s

conduct toward nature and human beings. While important

elements of our ecosophies may be shared, we each proceed

from assumptions, norms, and hypotheses that vary in sub-

stance and/or interpretation. Of central importance to

Naess’s exploration of ecophilosophy are norms and beliefs

about what one should or ought to do based on what is

prudent or ethical. Norms play a leading role in any ecophilo-

sophy. While science may explain nature and

human ecol-

ogy

, it is norms that justify and motivate our actions in the

natural world. Along with the concept of norms, Naess

stresses the importance of depth. By depth, Naess means

reflecting deeply on our concepts, emotions and experiences

of nature, as well as digging to the cultural, personal, and

social roots of our environmental problems. Thinking deeply

means taking a broad and incisive look at our values, life-

styles, and community life. In so doing, we discover if our

way of life is consistent with our most deeply felt norms.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nagasaki, Japan

An ecophilosophy which deeply investigates and clari-

fies its norms is called a “deep ecological philosophy.” A

social movement that incorporates this process, shares signif-

icant norms, and seeks deep personal and social change is

termed “deep

ecology

movement.” Naess coined the term

“deep ecology” in 1973, intending to highlight the impor-

tance of norms and social change in environmental decision-

making. He also coined the term “shallow ecology” to de-

scribe what he considered short-term technological solutions

to environmental concerns. Naess’s own ecophilosophy is

called “Ecosophy T.” The “T” symbolizes Tvergastein.

Eco-

sophy

T stresses a number of themes, including the

intrinsic

value

of nature, the importance of cultural and natural

diversity, and the norm of self-realization for persons, cul-

tures, and non-human life-forms. Naess offers his ecosophy

as a tentative template, encouraging others to construct their

own ecosophies.

Deep ecology is therefore a rubric representing many

philosophies and practices, each differing in significant ways.

Naess encourages this diversity, recognizing that many mu-

tually acceptable interpretations of deep ecology are possible.

On the whole, therefore, Naess is philosophically and envi-

ronmentally non-dogmatic. He avoids rigid dichotomies pit-

ting individual versus social accounts, liberal versus radical

solutions, or

wilderness

versus justice concerns. To para-

phrase Naess, “the frontier is long and there are many places

to stand.” Some may focus their thoughts and efforts on

nature, others on society, still others on culture. According

to Naess, these are legitimate and necessary foci and should

be encouraged as separate endeavors and joint undertakings.

[William S. Lynn]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Naess, A. “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movements.”

Inquiry 16 (1973): 95–100.

———. “Intrinsic Value: Will the Defenders of Nature Please Rise?” In

Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity, edited by M. E.

Soule. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 1986.

———. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Reed, P., and D. Rothenberg, eds. Wisdom in the Open Air: The Norwegian

Roots of Deep Ecology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Rothenberg, D. Is It Painful to Think? Conversations with Arne Naess.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

NAFTA

see

North American Free Trade

Agreement

934

Nagasaki, Japan

Nagasaki is a harbor city located at the southwestern tip of

Japan. It is Japan’s oldest open port. Traders from the western

world started arriving in the mid-sixteenth century. It be-

came a major shipbuilding center by the twentieth century.

It was the second city to be devastated by an atomic bomb

which was dropped on August 9, 1945, just 3 days after

the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The bomb that was

dropped at Nagasaki resulted in 35,000-40,000 men,

women, and children killed with an equal number injured.

Like Hiroshima, most of the city was destroyed. The Naga-

saki survivors of the atomic bomb have an increased risk for

radiation-induced

cancer

and are part of a continuing study

by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission which is now

known as the Radiation Effects Research Foundation

(RERF). The city was rebuilt after the end of World War

II and is now a tourist attraction.

[Robert G. McKinnell]

National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a private, non-

profit, self-governing organization that is responsibility for

advising the U.S. federal government, upon request and

without fee, on questions of science and technology that

affect policy decisions. NAS was created in 1863 by a con-

gressional charter approved by President Abraham Lincoln.

Under this same charter, the institution was expanded to

include sister organizations: in 1916 the

National Research

Council

was established, in 1964 the National Academy of

Engineering, and in 1970 the Institute of Medicine. Collec-

tively these organizations are called the National Academies.

NAS publishes a scholarly journal, Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences, organizes symposia, and calls

meetings on issues of national importance and urgency. Most

of its study projects are conducted by the National Research

Council rather than by committees within NAS. However,

NAS sponsors two committees, the the Committee on Inter-

national Security and Arms Control and the Committee on

Human Rights.

NAS is an honorary society that elects new members

each year, in recognition of their distinguished and continu-

ing achievements in original research. New members are

nominated and voted on by existing members. Election to

membership is one of the highest honors that a scientist can

receive. As of early 1999, NAS had 1,798 Regular Members,

87 Members Emeriti, and 310 Foreign Associates. More

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

National Academy of Sciences

The aftermath from the atom bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki during World War II. (UPI/Corbis-Bettmann.

Reproduced by permission.)

than 170 members have won Nobel Prizes. No formal duties

are required of members, but they are invited to participate

in the governance and advisory activities of NAS and the

National Research Council. NAS is governed by a Council,

comprised of twelve councilors and five officers elected from

the Academy membership. Committee members are not

paid for their work, but are reimbursed for travel and subsis-

tence costs. Foreign Associates are elected using the same

standards that apply to Regular Members, but do not vote

in the election of new members or in other deliberations of

the NAS.

NAS does not receive federal appropriations directly,

but is funded through contracts and grants with appropria-

tions made available to federal agencies. Most of the work

done by NAS is at the request of federal agencies. NAS is

responsive to requests from both the executive and legislative

branches of government for guidance on scientific issues.

NAS also cooperates with foreign scientific organiza-

tions. Officers of NAS meet with officers of the Royal Soci-

ety of England every two or three years. NAS represents U.S.

935

scientists as an institutional member of the International

Council of Scientific Unions.

The work and service of NAS and its sister organiza-

tions have resulted in significant and lasting improvement

in the health, education, and welfare of U.S. citizens.

[Judith L. Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hilgartner, Stephen. Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama (Writing

Science). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

National Academy of Sciences. The National Academy of Sciences: The First

Hundred Years, 1863–1963. Washington, DC: National Academy Press,

1978.

O

RGANIZATIONS

National Academy of Sciences, 2001 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W.,

Washington, DC United States of America 20007, Email: <http://www.

nas.edu>

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

National Air Toxics Information Clearinghouse

National Air Toxics Information

Clearinghouse

The National Air Toxics Information Clearinghouse

(NATIC) is a program administered by the

Environmental

Protection Agency

(EPA). This information network was

developed by the EPA to provide state and federal

air pollu-

tion control

experts with

air pollution

data. The computer-

ized data base is headquartered in North Carolina, but air

pollution control

officers nationwide are able to access

the data.

NATIC is a “one-stop shop” for emissions data for

state enforcement officers, according to the EPA. Included

on the network is information on air toxics programs,

ambi-

ent air

quality standards,

pollution

research, non-health

related impact of air pollution, permits, emissions invento-

ries, and ambient

air quality

monitoring programs.

National Ambient Air Quality

Standard

The key to national

air pollution control

policy since the

passage of the

Clean Air Act

amendments of 1970 are the

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQSs). Under

this law, the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA)

had to establish NAAQSs for six of the most common air

pollutants, sometimes referred to as criteria pollutants, by

April 1971. Included are

carbon monoxide

,

lead

(added

in 1977),

nitrogen oxides

,

ozone

,

particulate

matter, and

sulfur dioxide

.

Hydrocarbons

originally appeared on the

list of pollutants, but were removed in 1978 since they were

adequately regulated through the ozone standard. The provi-

sions of the law allow the EPA to identify additional sub-

stances as pollutants and add them to the list.

For each of these pollutants, primary and

secondary

standards

are set. The

primary standards

are designed

to protect human health. Secondary standards are to protect

crops, forests, and buildings if the primary standards are not

capable of doing so; a secondary standard presently exists

only for sulfur dioxide. These standards apply uniformly

throughout the country, in each of 247 Air Quality Control

Regions. All parts of the country were required to meet the

NAAQSs by 1975, but this deadline was extended, in some

cases, to the year 2010. The states monitor

air pollution

,

enforce the standards, and can implement stricter standards

than the NAAQSs if they desire.

The primary standards must be established at levels

that would “provide an adequate margin of safety ... to protect

the public ... from any known or anticipated adverse effects

associated with such air pollutant[s] in the ambient air.”

This phrase was based on the belief that there is a threshold

936

effect of

pollution

: pollution levels below the threshold are

safe, levels above are unsafe. Although such an approach to

setting the standards reflected scientific knowledge at the

time, more recent research suggests that such a threshold

probably does not exist. That is, pollution at any level is

unsafe. The NAAQSs are also to be established without

consideration of how much it will cost to achieve them; they

are to be based on the

Best Available Control Technology

(BAT). The secondary standards are to “protect the public

welfare from any known or anticipated adverse effects.”

The NAAQSs are established based on the EPA’s

“criteria documents,” which summarize the effect on human

health caused by each pollutant, based on current scientific

knowledge. The standards are usually expressed in parts of

pollutant per million parts of air and vary in the duration

of time a pollutant can be allowed into the

environment

,

so that only a limited amount of contaminant may be emitted

per hour, week, or year, for example. The 1977 Clean Air

Act amendments require the EPA to submit criteria docu-

ments to the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee and

the EPA’s Science Advisory Board for review. Several revi-

sions of the criteria documents are usually required. Al-

though standards should be based on scientific evidence,

politics often become involved as environmentalists and pub-

lic health advocates battle industrial powers in setting stan-

dards.

The six criteria pollutants come from a variety of

sources and have a variety of health effects.

Carbon

monox-

ide is a gas produced by the incomplete

combustion

of

fossil fuels

. It can lead to damage of the cardiovascular,

nervous, and pulmonary systems, and can also cause prob-

lems with short-term attention span and sensory abilities.

Lead, a heavy metal, has been traced to many health

effects, mainly brain damage leading to learning disabilities

and retardation in children. Most of the lead found in the air

came from

gasoline

fumes until a 1973 court case, Natural

Resources Defense Council v. EPA, prompted its inclusion

as a

criteria pollutant

. Lead levels in gasoline are now

monitored.

Nitrogen

oxide is formed primarily by fossil fuel com-

bustion. It not only contributes to

acid rain

and the forma-

tion of ground-level ozone, but it has been linked to respira-

tory illness.

Ground-level ozone is produced by a combination of

hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides in the presence of sunlight,

and heat. It is the prime component of

photochemical

smog

, which can cause respiratory problems in humans,

reduce crop yields, and cause forest damage. In 1979, the

first revision of an original NAAQS slightly relaxed the

photochemical oxidant standard and renamed it the ozone

standard. Experts are currently debating whether this stan-

dard is low enough, and in 1991 the American Lung Associa-