Fowler A. Mathematical Geoscience

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

150 3 Oceans and Atmospheres

where

f

x

=

F

φ

ρ

,f

y

=

F

λ

ρ

,f

z

=

F

r

ρ

. (3.36)

Following (3.4), we take the vector f =(f

x

,f

y

,f

z

) as

f =Fu, (3.37)

where

F =ε

H

∇

2

H

+ε

V

∂

2

∂z

2

, (3.38)

and

∇

H

=

∂

∂x

,

∂

∂y

. (3.39)

3.2.5 Non-dimensionalisation

There are three obvious length scales of immediate relevance. These are the depth

h of the troposphere, the radius r

0

of the Earth, and the length scale l of horizontal

atmospheric motions. We have h = 10 km, r

0

= 6370 km, and the largest (synop-

tic) scales of mid-latitude weather systems are observed to be l = 1000 km. These

lengths combine to form two dimensionless parameters,

δ =

h

l

,Σ=

l

r

0

(3.40)

both of which are small: δ ≈0.01, Σ ≈0.16. The ideas of lubrication theory, using

the fact that δ 1, suggest that in the vertical momentum equation,

∂p

∂z

≈−ρg, i.e.,

the pressure is approximately hydrostatic, as in our basic state. Lubrication theory

also suggests that if U is a suitable horizontal velocity scale, then the appropriate

vertical velocity scale is hU/l, in order that the material derivative retains vertical

acceleration.

Sphericity in the equations is manifested by the terms in 1/r and the trigonomet-

ric terms in λ.Thetermsin1/r are generally small, of order Σ or less, and serve as

a regular perturbation to the Cartesian derivative terms, except near the poles, where

tanλ →∞and a different discussion is necessary.

We scale the variables as follows:

x,y ∼l, z ∼h, u, v ∼U, w ∼δU,

t ∼

l

U

,ρ∼ρ

0

,p∼p

0

,T∼T

0

,

(3.41)

where we choose

p

0

=

ρ

0

RT

0

M

a

=ρ

0

gh (3.42)

3.2 The Geostrophic Circulation 151

(which actually defines h as the (dry) atmospheric scale height, cf. Question 3.2).

The length scales l and r

0

are those we have described, the horizontal wind speed

U is typically about 20 m s

−1

, and the density and temperature scales ρ

0

and T

0

are

their values at sea level. (These are determined by the mass of the atmosphere and

the effective radiative temperature.) For the moment we assume they are constant.

This is a reasonable approximation for p

0

but less so for temperature.

We then have dimensionless expressions

∇. u =μ

∂u

∂x

+

1

cosλ

∂(vcos λ)

∂y

+

∂w

∂z

+δΣ

x

∂w

∂x

+y

∂w

∂y

+2w

,

d

dt

=

∂

∂t

+u .∇ =

∂

∂t

+μu

∂

∂x

+v

∂

∂y

+w

∂

∂z

+δΣw

x

∂

∂x

+y

∂

∂y

,

(3.43)

and the momentum equations take the dimensionless form

Ro

du

dt

−v

sin λ +

1

2

Ro Σvtan λ

+δw

cosλ +

1

2

Ro Σu

=−

Ro

F

2

μ

ρ

∂p

∂x

+f

∗

x

,

Ro

dv

dt

+u

sin λ +

1

2

Ro Σutanλ

+

1

2

δRo Σvw =−

Ro

F

2

1

ρ

∂p

∂y

+f

∗

y

,

δ

δRo

dw

dt

−u cos λ −Ro Σ

u

2

+v

2

=−

Ro

F

2

1

ρ

∂p

∂z

+δΣ

x

∂p

∂x

+y

∂p

∂y

+1

+δf

∗

z

,

(3.44)

in which

λ =λ

0

+Σy, (3.45)

f

∗

k

=

f

k

2ΩU

for k =x, y, z, (3.46)

and the extra parameters are a form of the Rossby number,

Ro =

U

2Ωl

, (3.47)

and the Froude number

F =

U

√

gh

. (3.48)

For U = 20 m s

−1

, Ω = 0.7 × 10

−4

s

−1

, l = 10

3

km, g = 10 m s

−2

, h = 10 km,

we have Ro ≈ 0.14, F ≈ 0.06, and thus F

2

/Ro ≈ 0.03. Evidently the pressure is

essentially hydrostatic, as we expect for a shallow flow.

152 3 Oceans and Atmospheres

The energy equation is commonly written in terms of the potential temperature,

defined as

θ =T

p

0

p

R/M

a

c

p

; (3.49)

the usefulness of this variable lies in the fact that

ρc

p

T

dθ

θ

=ρc

p

dT −dp, (3.50)

so that θ is constant for the dry adiabatic basic state of Question 3.2.

8

If we scale θ

as well as T with T

0

, then the dimensionless definition of θ is

θ =

T

p

α

, (3.51)

in which

α =

R

M

a

c

p

. (3.52)

The equation of state is simply

ρ =

p

T

. (3.53)

The dimensionless energy equation takes the form

p

θ

dθ

dt

=

1

Pe

∂

∂z

k

∗

∂T

∂z

+O

δ

2

+Q

∗

a

+C

∗

; (3.54)

the reduced Péclet number, internal heating rate and condensation rate are given by

Pe =

Uh

2

κ

0

l

,Q

∗

a

=

Q

a

l

ρ

0

c

p

T

0

U

,C

∗

=

LClρ

c

p

T

0

U

, (3.55)

where we have written

¯

k =k

0

k

∗

(k

∗

=O(1)), (3.56)

and

κ

0

=

k

0

ρ

0

c

p

. (3.57)

8

Thus s =c

p

lnθ ,wheres is entropy.

3.2 The Geostrophic Circulation 153

3.2.6 Day and Night, Land and Ocean

The thermal boundary condition at the ground is a flux condition as given in (3.12)

and (3.14). In dimensionless terms, the heat flux is

−k

∗

∂T

∂z

=q

∗

0

at z =0, (3.58)

where

q

∗

0

=

q

0

h

k

0

T

0

. (3.59)

The heat flux scale k

0

T

0

/h ≈ 10

4

Wm

−2

(see Sect. 3.2.7 below), while the com-

bined radiative and sensible heat flux from the ground is q

0

≈ 102 W m

−2

. Thus

q

∗

0

≈ 0.01, and is very small. Equally, the heat flux through the tropopause is very

small. The point is that the time scale of response of the energy balance of the at-

mosphere is much longer, O(10

7

) seconds, than the shorter response time of atmo-

spheric dynamics, l/U ∼ 10

5

seconds. In this sense, the energy of the atmosphere

is like the water in a bath, being filled by a tap and emptied through the plug hole.

The source and sink are small, and control the amount of water in the bath over a

long time scale, while the dynamics of the motion have a much faster time scale.

There is a fundamental distinction between land and ocean, and between day

and night. In the ocean, the temperature must remain at or below the saturation

temperature and above the freezing temperature. At saturation, the thermal boundary

condition (3.14) determines the rate of evaporation; the thermal boundary condition

is that T = T

sat

, the saturation temperature. If T<T

sat

, then E = 0 and the sea

surface temperature is set by the incoming radiation, as we must have

σT

4

=q

0

=q

s

+q

−

. (3.60)

The same is true on land, except that since evaporation is essentially absent, the

surface temperature is always determined by incoming short wave radiation.

Evidently, it is cold at night and warm in the day. At sea, evaporation switches

on in the daytime. As the moist air is brought by the circulation over the warm

land, it rises and thus forms clouds through condensation at higher (thus cooler)

altitudes. The clouds we see scudding across the sky are the tops of convective

plumes weaving their way across the countryside. This is why it always rains in

Seattle, for example.

9

I live in the Thames valley, say 100 km east of Bristol, perhaps 200 km from the

sea. At that distance a wind of 20 m s

−1

takes 10

4

s, about three hours, to make its

way from the sea. And indeed, it is commonly the case on a Sunday morning that

the skies are clear in the early morning, but by mid-morning it has clouded over.

This is why.

9

The effect is worsened by the topographic effect of the coastal mountain range.

154 3 Oceans and Atmospheres

3.2.7 Parameter Estimates

We have already estimated typical values δ ≈0.01, Ro ≈0.14, F ≈0.06, Σ ≈0.16,

and we need further to estimate values of f

∗

k

, Pe, Q

∗

a

and C

∗

. We estimate the

internal radiative heating Q

a

h ∼ 0.2q

i

∼ 68 W m

−2

; using values ρ ≈ 1kgm

−3

,

h ≈ 10 km, c

p

≈ 10

3

Jkg

−1

K

−1

, l = 10

3

km, T

0

= 288 K, U = 20 m s

−1

,we

obtain Q

∗

a

∼ 1.2 × 10

−3

. Internal radiative heating is therefore very small: this is

consistent with the discussion concerning thermal boundary conditions above.

In order to estimate Pe and f

∗

k

, we need estimates of eddy viscosities. A typ-

ical estimate in the horizontal is ε

H

∼ 0.1Uh ∼ 10

4

m

2

s

−1

, and a typical esti-

mate in the vertical is ε

V

∼ 0.1δUh ∼ 10

2

m

2

s

−1

. Therefore ε

H

∇

2

H

∼ 10

−8

s

−1

,

ε

V

∂

2

/∂z

2

∼ 10

−6

s

−1

, so that the vertical diffusivity is dominant. Then f

∗

x,y

∼

ε

V

/2Ωh

2

∼10

−2

, while f

∗

z

∼δf

∗

x,y

.

We already estimated Pe ∼ 20 in Question 2.10, based on a radiative effective

thermal conductivity of k

R

≈ 10

5

Wm

−1

K

−1

. A corresponding estimate for the

(vertical) eddy thermal conductivity is k

T

≈ρc

p

ε

V

≈10

5

Wm

−1

K

−1

, comparable

to the radiative value. This suggests that

¯

k ∼k

0

≈2 ×10

5

Wm

−1

K

−1

is a reason-

able estimate, which would then suggest that Pe ∼10.

In order to estimate the dimensionless condensation rate C

∗

,weuse(3.15). The

eddy diffusive term is small relative to the advective term (the ratio is of order

ε

V

l/Uh

2

∼0.05), and is only of concern within the planetary boundary layer, so we

can take C ≈−dm/dt, assuming saturation. We use the formula in Question 2.12

for p

SV

,

p

SV

=p

0

SV

exp

a

1 −

T

0

T

, (3.61)

where

a =

M

v

L

RT

0

. (3.62)

Appropriate values are a ≈18.8 and p

0

SV

≈1,688 Pa.

10

From these we find

m =

M

v

p

0

SV

M

a

p

exp

a

1 −

T

0

T

, (3.63)

and in terms of the dimensionless temperature and pressure,

m =νM(T , p), (3.64)

10

This is different from the triple point value of 600 Pa because we use 288 K as the reference

temperature, not 273 K.

3.2 The Geostrophic Circulation 155

where

11

M(T,p) =

1

p

exp

a

1 −

1

T

, (3.65)

and

ν =

M

v

p

0

SV

M

a

p

0

. (3.66)

Approximately, ν ≈0.01. In dimensionless terms, we thus have

C

∗

=νSt

−ρ

dM

dt

, (3.67)

where the Stefan number is

St =

L

c

p

T

0

. (3.68)

The value of St is 8.7, so that νSt ≈ 0.087. Because a is large and M is O(1),

dM/dt ∼aM, and thus C

∗

∼O(1) (the value of νSt a is ≈1.6).

3.2.8 Basic Reference State

Using the definitions of M in (3.65), and of ρ and T in (3.53) and (3.51), we can

write the energy equation (3.54) in the form

p

θ

1 +

νSt aM

T

2

dθ

dt

=−

νSt M(αa −T)

T

2

dp

dt

+

1

Pe

∂

∂z

k

∗

∂T

∂z

, (3.69)

in which we neglect Q

∗

a

and O(δ

2

Pe).

If we further neglect the conductive term of O(1/Pe), then to leading order,

(3.44) and (3.69) can be written as

∂p

∂z

=−ρ,

p

θ

1 +

νSt aM

T

2

dθ

dt

=−

νSt M(αa −T)

T

2

dp

dt

, (3.70)

representing a wet adiabatic hydrostatically balanced atmosphere. This tells us that

in such an atmosphere, θ is a well-defined function of p, and hence (because of

hydrostatic balance) also of z. We define this basic wet potential temperature func-

tion as θ

w

(p), and the corresponding pressure and density profiles as p

w

and ρ

w

.

11

This definition of M should not be confused with its use as the tropospheric latent heat term in

(3.24), which we no longer have use for.

156 3 Oceans and Atmospheres

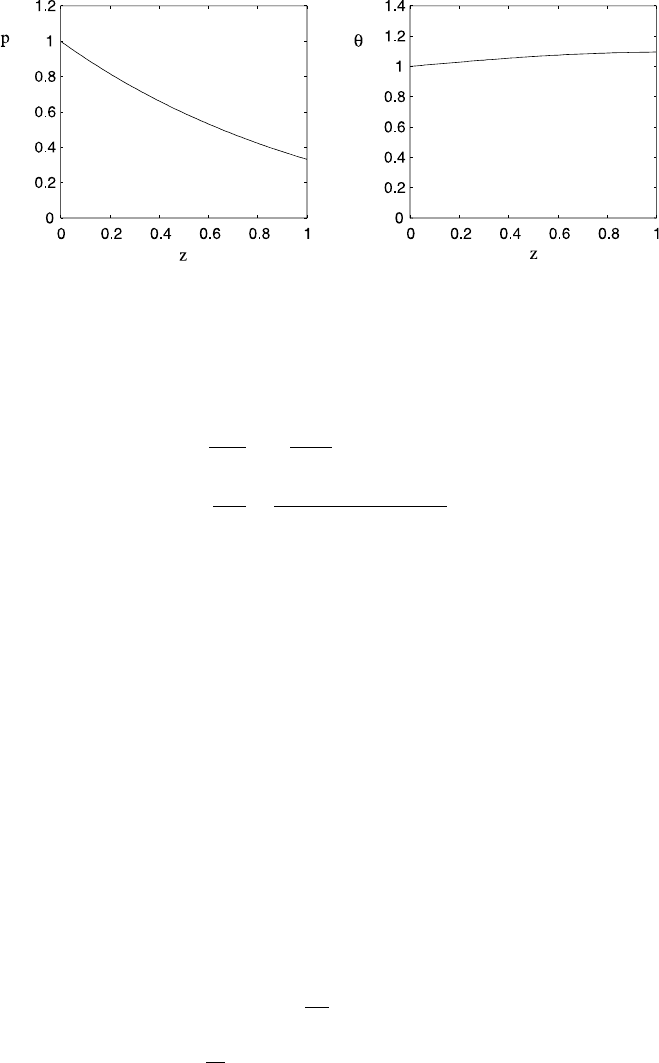

Fig. 3.1 Solution of (3.71). The pressure is excellently approximated by p ≈ e

−1.08z

,andthe

potential temperature is excellently approximated by θ ≈ 1 +0.15z −0.05z

2

Thus θ

w

and p

w

are determined by solving the simultaneous differential equations

(noting that ρ =p

1−α

/θ and T =θp

α

)

dp

w

dz

=−

p

1−α

w

θ

w

,

dθ

w

dz

=

νSt (aα −θ

w

p

α

w

)M

[θ

2

w

p

2α

w

+νSt aM]p

α

w

,

(3.71)

with p

w

=θ

w

=1atz =0. We have α ≈0.29, a ≈ 18.8, and thus αa ≈ 5.45, and

so dθ

w

/dz > 0. Also ν ≈0.01, St ≈8.7, so that νSt ≈0.087, and the potential tem-

perature gradient appears on this basis to be small, of O(Ro). Figure 3.1 shows a

numerical solution of (3.71), which shows that pressure decreases approximately

exponentially (with scale height of about 10 km) and θ

w

increases approximately

linearly, in this model. The numerical solution indicates that the potential temper-

ature gradient is indeed small, of order 0.1. We associate this with the fact that

νSt ≈ 0.087 is small. Below, we define a parameter ε (the Rossby number) which

is of the same order as the wet potential temperature gradient; then θ

w

=1 +O(ε)

defines a wet adiabat, whereas a dry reference state in which the moisture term is

absent is simply θ = 1. Reality is somewhere between the two, though nearer the

wet state.

3.2.9 A Reduced Model

In order to approximate the model, we note that

δ ∼RoΣ ∼

F

2

Ro

∼f

∗

x,y

∼10

−2

,

1

Pe

∼νSt ∼Ro ∼Σ ∼10

−1

,

(3.72)

3.2 The Geostrophic Circulation 157

and the other parameters Q

∗

a

and f

∗

z

are much smaller. These suggest that we should

think of 1/Pe, νSt, Ro and Σ as small, but an order of magnitude larger than δ and

F

2

/Ro. In fact, ∂T/∂z ∼ α, and α/Pe ≈0.04; therefore we shall consider the con-

ductive term in (3.69)tobeofO(δ) (see also Question 3.3). In fact, to be specific,

we now define the length scale l and velocity scale U by requiring that

F

2

sin λ

0

Ro

=

α

Pe

=ε

2

, (3.73)

where it is conventional to define the Rossby number as

ε =

Ro

sin λ

0

=

U

fl

, (3.74)

in which the Coriolis parameter f is defined as

f =2Ω sin λ

0

. (3.75)

This leads to definitions

U =

ακ

0

g

fh

1/2

,l=U

h

2

ακ

0

f

2

1/3

, (3.76)

and calculation of these using values used previously leads to U ≈ 26 m s

−1

, l ≈

1290 km.

Next, we adopt the formal asymptotic limits

νSt ∼Ro ∼Σ ∼ε,

δ ∼RoΣ ∼f

∗

x,y

∼ε

2

.

(3.77)

Expanding the equations in powers of ε, the vertical momentum equation is

∂p

∂z

≈−ρ +O

ε

3

, (3.78)

where

ρ =

p

T

,θ=

T

p

α

. (3.79)

Also,

∇. u ≈μ

∂u

∂x

+μ

∂(v/μ)

∂y

+

∂w

∂z

+O

ε

3

,

d

dt

=

∂

∂t

+u .∇ ≈

∂

∂t

+μu

∂

∂x

+v

∂

∂y

+w

∂

∂z

+O

ε

3

,

(3.80)

158 3 Oceans and Atmospheres

the horizontal momentum equations are approximately

ε sin λ

0

du

dt

−v sin λ =−

sin λ

0

ε

2

μ

ρ

∂p

∂x

+O

ε

2

,

ε sin λ

0

dv

dt

+u sin λ =−

sin λ

0

ε

2

1

ρ

∂p

∂y

+O

ε

2

,

(3.81)

and the energy equation is approximately

p

θ

1 +

νSt aM

T

2

dθ

dt

=−

εsM(αa −T)

T

2

dp

dt

+ε

2

∂

∂z

k

∗

α

∂T

∂z

, (3.82)

where we have written

νSt =εs (3.83)

to delineate the smallness of νSt (but noting that νSt a ≈1.64 is O(1)). Together

with the conservation of mass equation

dρ

dt

+ρ∇. u =0, (3.84)

this completes the basic approximate model, valid locally everywhere except near

the poles (where μ and tanλ →∞). There are seven equations in (3.78), (3.79),

(3.81), (3.82) and (3.84) for the seven variables θ, ρ, T , p, u, v and w. The frictional

terms f

∗

x,y

can be neglected in the main flow, but they are important in the planetary

boundary layer, as we discuss later.

3.2.10 Geostrophic Balance

Geostrophic flow is described by the leading order approximation which considers

both curvature and inertial effects to be small, that is, ε 1. At leading order, the

pressure is hydrostatic, and (3.81) indicates that the correction is of O(ε

2

).This

is consistent with (3.82), which indicates that θ =

¯

θ(z) + O(ε

2

). We do not yet

assume that

¯

θ is equal to the reference state θ

w

defined in (3.71); this would have to

be deduced. But we do anticipate that

¯

θ

(z) =O(ε) (since also θ

w

=O(ε)). We put

p =¯p(z) +ε

2

P, (3.85)

where ¯p is the hydrostatic pressure corresponding to

¯

θ, and we denote the corre-

sponding density and temperature as ¯ρ and

¯

T . Then, since μ ≈1, λ ≈λ

0

and ρ ≈¯ρ,

the momentum equations become

¯ρv ≈

∂P

∂x

,

¯ρu ≈−

∂P

∂y

,

(3.86)

3.3 The Planetary Boundary Layer 159

and mass conservation reduces to

∂( ¯ρu)

∂x

+

∂( ¯ρv)

∂y

+

∂( ¯ρw)

∂z

≈0. (3.87)

Together (3.86) and (3.87)imply

∂( ¯ρw)

∂z

=0, (3.88)

and thus w is determined by its value on the surface, where it is prescribed by the

no flow-through boundary condition. In the absence of topography, we have w =0

at z = 0, so that w = 0 everywhere. The flow is purely two-dimensional, and the

horizontal velocity vector u

H

=(u, v) is given by

¯ρu

H

=k ×∇

H

P, (3.89)

where ∇

H

=(

∂

∂x

,

∂

∂y

).(3.89) defines the geostrophic wind, and shows that

u

H

.∇

H

p = 0, i.e., wind velocities are along isobars. In the northern hemisphere,

the wind moves anti-clockwise about regions of low pressure (depressions, or cy-

clones). The closer the isobars, the higher the wind speed.

3.3 The Planetary Boundary Layer

By neglecting the frictional terms in (3.29), we are unable to satisfy the condition

of no slip at the Earth’s surface. We now reconsider these terms in order to see

how this condition can be met. Although the frictional terms are small, they become

important in the planetary boundary layer, a layer with a depth of about a kilometre

adjoining the surface.

Following (3.37) and (3.46), we add the dimensionless friction terms to (3.81),

to obtain

−v =−

1

¯ρ

∂P

∂x

+E

∂

2

u

∂z

2

+O(ε),

u =−

1

¯ρ

∂P

∂y

+E

∂

2

v

∂z

2

+O(ε),

(3.90)

where the Ekman number is given by

E =

ε

V

fh

2

. (3.91)

With f ∼10

−4

s

−1

, ε

V

∼10

2

ms

−1

, h ∼10

4

m, we have E ∼10

−2

∼ε

2

as previ-

ously stated.

The frictional terms are indeed negligible, except in a boundary layer of thickness

ε, in which we rescale

z =εZ, w =εW, (3.92)