Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cities

130

local lord. In Italy, these festivals usually meant horse races right through

the middle of town. In other towns, they meant entertainers with perform-

ing animals or group games such as mock battles. Guilds often put on mir-

acle or mystery plays. At the very least, a town usually had a fair to honor

their patron saint and collect annual trading tolls.

Great Medieval Cities

Constantinople

The greatest of the medieval cities was Constantinople. It was the largest

and most populous city, as well as the center of an empire. It was also a ma-

jor manufacturing center. Before the 11th century, the city was a closed

market that housed foreign merchants in a special part of the city and did

not permit them free access to its goods. It was not a typical medieval city;

it was on the fringes of medieval Europe, although it was at the center of

its own world.

Medieval Constantinople was not well studied as a city, even in its time;

foreigners had such a limited view of it that their reports tended to empha-

size either the glories of the churches and palaces or the squalor of the sec-

tion of the city where they were lodged. Its chief strength lay in its location.

It was able to charge fees and duties on a wide variety of merchant ships

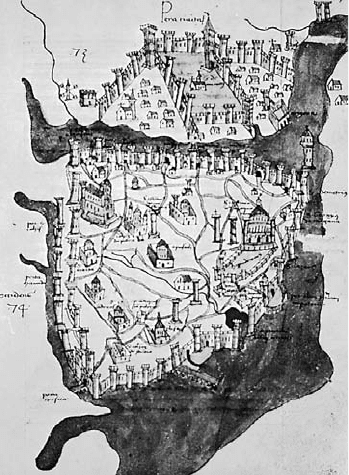

Before its fall to the Turks,

Constantinople was the most heavily

guarded city in Europe. Even with

water (either sea or river) surrounding

most sides, the city was entirely ringed

with multiple heavy walls. Its heaviest

gates faced the side unprotected by

water. Constantinople was also the

most populous city in Europe; its

streets defi ed a medieval map maker’s

skill. As a center of both manufacture

and commerce, the city was a maze of

shops, alleys, warehouses, and ethnic

quarters. (E&E Image Library/

StockphotoPro)

Cities

131

passing through the Strait of Bosporus. This, rather than its own merchant

fl eets, was probably the source of its wealth. Further, its location on the

point of the Golden Horn was easy to defend against invasion. The few

successful attacks depended on treachery inside the walls, such as someone

opening a gate. Until the invasion by the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Constan-

tinople had never been ruined. Its concentric walls were an engineering mar-

vel and impervious to pre- gunpowder attack, and the city routinely used

Greek fi re in defensive catapults. After the Turkish invasion in 1453, when

enormous cannons battered the outer walls, much of the medieval charac-

ter of the city was altered, and many records were lost.

Constantinople’s infrastructure was developed beyond the possibilities

of newer cities. Situated on a large body of salt water, it had only one small

river bringing fresh water, so the city built a large network of aqueducts that

went over and under the city walls. Underground cisterns large enough to fi t

modern sports fi elds ranged under the city streets, supported by pillars and

vaulted roofs. The city government also purchased grain from all the ter-

ritories it ruled and stored it in warehouses to ward off shortage. Local fi sh-

ermen were required by law to sell fi sh only to the city. Constantinople’s

absolute ruler, the emperor, had power to tax and regulate beyond the

more limited powers of the Italian communes or the feudal cities of North-

ern Europe. Both city services and the emperor’s extremely luxurious life-

style were funded by direct taxes on land and business activity.

Constantinople had a rigid class system protected by sumptuary laws.

Types of cloth and jewelry were designated as appropriate for certain

classes, and the laws appear to have been enforced at the point of sale. A large

number of goods were not permitted to be exported, since the Byzantine

aristocracy preferred to keep them as markers of their privilege. This in-

cluded some kinds of silk that inspectors confi scated if anyone tried to buy

them to load onto ships.

The poorer sections of the city were dark, dirty, and crowded. The city

grew very fast and without controlled planning. Tenement buildings were

often four stories high, with a family (and sometimes animals) in each fl at.

They were built without regard to sanitation and health, too close together,

blocking the sunlight. The overwhelming tide of poor residents sometimes

turned to mob violence, especially during political coups or against foreigners.

Constantinople had a very large population of foreigners from its prov-

inces and trading partners. Although the movement of foreigners was tightly

controlled, certain sections of the city were allowed a Venetian or Jewish

quarter. A number of foreign churches were in these neighborhoods, in-

cluding mosques and synagogues. Foreign neighborhoods were not in the

best areas, which were reserved for privileged Byzantine natives.

The city also had more public institutions than its peers in Europe. There

were large prisons at a time when other medieval cities had nothing more

Cities

132

than gatehouses. The Roman tradition had provided them with a hippo-

drome for public chariot races and other kinds of entertainment; the en-

tertainment, such as animal fi ghts, was often violent. Christian emperors

endowed hospitals during the 11th and 12th centuries. These hospitals were

primarily for the poor, since the wealthy could afford nursing care when

they were sick or injured. Some hospitals functioned as orphanages or nurs-

ing homes for the elderly, but some were organized around treating spe-

cifi c illnesses and injuries. Surgeons’ and physicians’ fees were paid by the

state.

By the 14th century, when the Northern European cities were coming

into their own, Constantinople was struggling. Its territories had been lost

to Muslim invasions, and it had become an embattled fortress. Many of its

luxuries and relics had been stolen by Venetian sailors and Crusaders in 1204,

and the city had never quite recovered. It was a shrinking power when the

others were expanding.

Venice

Venice had the most unusual building site and history among the Euro-

pean cities. Founded by Roman refugees from the barbarian invasions, it was

built on a cluster of small islands just off the shore of Italy. Several rivers had

created deltas out from the shore in irregular shapes dotted with islands, and

long barrier islands protected the lagoon from sea waves. Venetians used the

water as a natural moat and built their city on the close-lying Rialto islands;

the water between the islands became the main canals. By draining marshy

land and building artifi cial canals, the residents made the most of the islands’

size. Most early buildings were wooden, built from pine trees on the main-

land shore. In many places, logs were driven as piles into the soft ground to

form platforms fi rm enough for stone buildings.

From the start, Venice aimed at becoming one of the leading cities of It-

aly. The city’s fi rst claim to international fame was its ninth-century acquisi-

tion of the body of Saint Mark, writer of the Gospel of Mark. His symbol as

an evangelist was the lion, a symbol Venice took for itself. Saint Mark’s Ba-

silica is one of its greatest buildings. It was built in the Byzantine style and

is still famous for its mosaics.

The Doge’s Palace (Duke’s Palace), built on the water, was rebuilt several

times until, in the 14th century, it became a jewel of Gothic style. In honor

of Saint Mark, the doge kept lions in a courtyard, and some public view-

ing was permitted. In 1316, the lioness gave birth to visibly living cubs, al-

though bestiaries confi dently informed readers that lion cubs were always

born dead and were brought to life after three days by their mother’s licking.

Venice built more ships than any other European city. Its commercial

power was based on trading ships, and it had no fi ghting men except for

Cities

133

its navy. The Arsenal was a fortress that served as a shipbuilding workshop.

It was built on two small islands that became part of the main island com-

plex through land reclamation, canals, and bridges. The word arsenal came

from Arabic dar sina’a, “house of construction.” Within its walls were large

square bays, docks, and workshops for blacksmiths, carpenters, and rope

and sail makers. The new rib-and-plank construction method of the 12th

and 13th centuries began in the Arsenal; ships were built around a skeleton,

rather than upward from the keel.

The city government, under the doge, may have been the largest, most

controlling government in Europe. The Arsenal’s workshops were owned

by the Republic, as were all the ships it built. The doge had a network of civil

servants, lawyers, notaries, tax collectors, and inspectors. In the 14th century,

the city had free hospitals and a medical school. Venice’s surgeons were re-

quired by law to meet and discuss cases to share their knowledge. There was

a service for identifying and assisting (and no doubt watching) travelers and

strangers. Garbage had to be collected by canal boat, a highly organized city

service. When the Black Death came to Venice, the city’s social infrastruc-

ture was among the few that held up during the crisis. Garbage collections,

including for corpses, never stopped, although the boatmen themselves

were as hard-hit by the plague as anyone.

In the 14th century, the islands continued to have open spaces for fi sher-

man’s cottages and gardens. Venice never had large-scale farming of grain,

but, as in other European cities, there were many vegetable-farming plots.

Packed-dirt streets crossed the canals with drawbridges. Although the city

had many fi shing boats, the canals did not yet have the city’s beautiful Re-

naissance gondolas. However, Venice’s canals were the fi rst European streets

to have lights at night. In the early 12th century, the doge ordered the city

to pay for lamps to stand in the many saints’ shrines at canal intersections

and along the main routes. Parish priests were responsible for maintaining

and lighting these lamps.

London

London of the 14th century was still a walled city with seven gates. Two

of the gates had prisons built into them. The city had a curfew. At about nine

at night, the city gates closed, and taverns were supposed to close. Work-

shops had closed at sunset since guilds prohibited work by lamp or candle.

The city employed guards to pace the streets, keeping order. Even in the

late Middle Ages, most city people lived inside the walls, and outside the

walls was largely countryside. Suburbs were built after the Middle Ages.

London had many small church parishes; people attended the nearest

assigned parish church so that parishes functioned as cohesive neighbor-

hoods. There were over 100 parishes in 14th-century London. The city

Cities

134

was divided into 25 wards, each comprising several parishes, which func-

tioned as governmental units. An alderman, a beadle, and sergeants heard

disputes between neighbors, regulated building codes, inspected shops,

and carried out sanitation measures. Each ward kept records of its inhabit-

ants, registering new freemen as they moved into the ward.

The typical city house at this time had three stories, each ranging from

7 to 12 feet tall, and was about 12 feet wide along the street. Wealthier merc-

hants owned houses and shops with more frontage along the street and

rented out some shops while enjoying the larger lot’s back courtyard for

their families. In the 12th century, London outlawed thatched roofi ng and

stipulated that walls of adjoining houses must be thicker than the usual wat-

tle and daub; they must be three feet thick. Upper stories could be cantile-

vered out over the street as long as they allowed a nine-foot clearance for a

man on a horse. These projections were called penthouses. In some cases, a

building rented its fl oors as fl ats, and each upper-story fl at was reached by

a ladder or stair on the outside. Neighbors had to be careful not to dump

wastewater on each other’s heads or balconies.

When a family occupied all fl oors of their building, the shop was on the

ground fl oor and at the front, with a hall behind it and the kitchen at the

back. The hall was still the main common room, as in the plan of a castle or

manor with its grand hall. It had a fi replace and an eating area. Valuables were

kept locked up in the master’s bedroom on the second fl oor, and the mas-

ter’s children also slept in this room. As in a castle, this private room on the

second fl oor was called the solar. The third-fl oor garret, under the peaked

roof, was the room for servants and apprentices.

Many fl ats and houses in the city belonged to the church, having been

left as donations in wills. The church rented them to families or to the poor,

depending on their condition. People often rented single rooms and usually

had their food (their place at the “board”) included with the room.

Shops along the street had colorful pictorial signs, and taverns marked

their trade with a green bough. Most shops had shutters that projected

into the street when they were open for business. Some built displays out

into the street, but these booths were supposed to be portable (able to be

taken down at sunset) and not project more than three feet into the road.

The main window, with its open shutters, had a shelf where the shop’s wares

were displayed. The artisan sat near the window, using its light to continue

his work. He was able to keep an eye on his displayed wares and talk to cus-

tomers who stopped to look.

City neighborhoods were not socially stratifi ed in medieval times. Peo-

ple lived above or in their shops, and they had to be able to buy what they

needed within walking distance, so every ward in London was crowded with

many kinds of businesses. Craftsmen, tavern keepers, and prostitutes lived

in the same block. Brothels in London were called stewhouses (like com-

Cities

135

mercial bathhouses) and were not legal, but they operated in a gray area as

long as they were not nuisances. Many prostitutes operated out of taverns

fairly openly.

On the other hand, some trades clustered in places. Merchants and fi sh-

mongers clustered near harbors and docks. Smelly, polluting trades like

butchering and tanning were usually restricted to a certain area, often just

outside the oldest town walls. Butchers and merchants usually did well, so

although these sectors of the city were closest to their trades, they had the

grandest houses and cleanest streets.

Paris

Paris began as a citadel on an island ( Île de la Cité ) in the middle of the

Seine River. During the early 13th century, King Philip II built a new, larger

wall around Paris. The new wall defi ned a city that spread onto the riverbanks

around the island, nearly half a mile on each side. At the time, the Right

Bank included a number of farms and villages, and the Left Bank was domi-

nated by vineyards. There were six gates in the wall on the Right Bank and

fi ve gates on the Left Bank. The king planned for the city to grow into its new

walls, and, by the 14th century, it had fi lled them. The Right Bank grew

faster, and its wall had to be expanded. In time, it became the main city. The

Left Bank came to house the university.

Streets in Paris were sometimes named for the activities that took place

on them: a minstrels’ school gave the rue des Menestrals its name. Others

were named for saints or for earlier vineyards or farms. Most were dirt, but

Philip II ordered the main streets to be paved so they could be cleaned more

effi ciently. Residents were supposed to pave the streets by their houses or

shops, but few did. Streets were maintained and cleaned with tolls collected

from merchants going in and out of the city gates. The bridges to the cen-

tral island were also toll points.

Titled aristocrats such as the duke of Burgundy maintained mansions in

the city. These palaces had galleries linking their wings and rooms, gardens

with fountains, and hundreds of servants. In French, the grand houses were

called hôtels, but they were not inns. As the city of Paris grew, some mer-

chants or civil servants of the king grew very wealthy and formed an urban

aristocracy without titles. Mansions inside the city were built on several lots

or by renovating several existing houses into one unit. Lower rooms were

salons, great halls for receiving visitors. Ostentatious displays of wealth re-

quired costly imported fabrics, exotic animals like peacocks, and leisure

equipment such as board games. Upper chambers had windows with views

of the city, since these mansions were taller than other houses.

Working-class houses, usually rented, fi lled most of the city. As in other

medieval cities, some trades clustered in convenient places, but others mixed

Climate

136

into all neighborhoods. Artisans normally worked on the ground fl oor of

the houses they lived in, with front window access to customers in the street.

Single families lived in these houses, as a rule, but extended families often

gathered in the same block.

Women seem to have carried on trades in Paris more freely than in some

other places. Lists of Parisian taxpayers include women who kept taverns,

sold grain, wove and embroidered, and sold groceries or vegetables. Most

worked in a cloth-related industry, such as dressmaking, silk spinning, or

laundry. Some may have been carrying on their husbands’ businesses, such

as pottery or glazing. A few worked in medicine as nurses or midwives.

See also: Gardens, Hospitals, Houses, Latrines and Garbage, Prisons, Roads.

Further Reading

Coldstream, Nicola. Medieval Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Dean, Trevor. The Towns of Italy in the Later Middle Ages. Manchester, UK: Man-

chester University Press, 2000.

Gies, Joseph, and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval City. New York: Harper and

Row, 1969.

Hanawalt, Barbara A. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Child-

hood in History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Harris, Jonathan. Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. New York: Continuum, 2007.

Hindle, Paul. Medieval Town Plans. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications, 2002.

Hunt, Edwin S., and James M. Murray. A History of Business in Medieval Europe,

1299–1550. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Lilley, Keith D. Urban Life in the Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2002.

Pirenne, Henri. Medieval Cities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1939.

Pounds, Norman. The Medieval City. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Roux, Simone. Paris in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2009.

Singman, Jeffrey. Daily Life in Medieval Europe. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1999.

Waley, Daniel, and Trevor Dean. The Italian City-Republics. New York: Longman,

2010.

Climate

The climate of Europe during the 1,000 medieval years went through sev-

eral major changes. Climate scientists usually speak of two main periods

when it was fi rst warmer, and then colder, than Europe’s historical average.

At some point in the early Middle Ages, Europe warmed—a period called

the Little Optimum, or the Medieval Warm Period. After 1300, the conti-

nent experienced a long, intermittent period of overall colder tempera-

tures and harsher weather. The average temperatures were not dramatically

Climate

137

different—not more than one degree Celsius warmer or colder than in the

20th century—but the difference was enough to make dramatic changes in

human life. This colder period, lasting several centuries into modern times,

is usually known as the Little Ice Age.

Medieval Europe had no system of measuring temperature. Modern sci-

entists estimate temperatures based partly on direct observation of tree

rings, lake sediment, arctic ice, and other natural fi ndings. They also observe

human behavior, as witnessed in the archeological record and as recorded

in accounts. Villages at high or low altitudes were founded or abandoned as

the climate changed. Household, guild, and city records can help track

farming trends. Late planting suggests a cold spring; high grain prices sug-

gest poor harvests. Sailors must avoid pack ice, so by reading records of voy-

ages, we can have some sense of which ocean passages were open, indicating

warmer temperatures. Some medieval observers recorded the weather they

saw, especially if it was extreme.

Around 800, the Norse began sailing farther west toward North Amer-

ica. They sailed through passages south of Greenland that had been closed

by pack ice. The ocean surface was warmer, and all arctic ice retreated. Gla-

ciers shrank in Norway, Iceland, and Greenland and in the Alps as well. The

Norse not only settled in Iceland and Greenland but also sailed to Labrador

in search of timber. Iceland was better able to support farming, and there

were two zones of Greenland with growing seasons long enough to raise

wheat and hay.

In continental Europe, the temperatures were on average warmer than in

past or future centuries. Summers were long and harvests were good. Frost

ceased during April, and snow did not fall until December. People began

settling on mountain slopes that had previously been too cold. They built

villages on the slopes of the Alps, and they reopened prehistoric copper

mines that had been covered by glaciers. Northern England and Scotland

could grow grain in places that now cannot support serious farming, and

some farmers in southern England succeeded in growing grapes for wine.

Farming spread into valleys and hillsides in Norway that now cannot grow

crops. They were able to grow wheat around Trondheim.

Rainfall was higher but not unseasonable, and many rivers were wider and

more navigable. Water was warm enough for a fi sh of the Danube River—

the carp—to migrate into the colder rivers of Northern Europe. The sea level

was higher. Some coastal towns that became important f ishing ports are

now far inland, after the sea level dropped.

Polar ice began to grow during the 13th century, making shipping dif-

fi cult around Greenland and Iceland. Glaciers in the Alps began to grow

again, covering farmland that had been cleared during the warm centuries.

In most of Europe, the warm weather and good farming lasted through

1300, when a set of adverse weather conditions began fairly suddenly. There

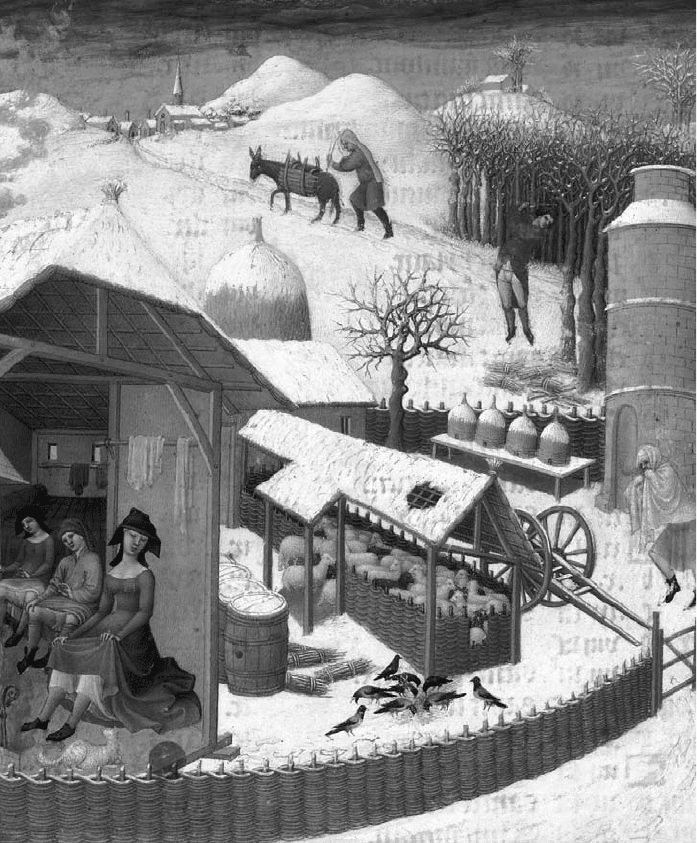

Europe’s peasant farmers had more diffi cult winters after the 14th century. Forests

were already thinning from industrial overuse when peasants found that they needed

more wood to keep their houses warm. Their winter clothing was not adequate for

colder, snowier seasons. Animals were no longer kept under the same roof as humans,

so keeping the animals from freezing now became a problem. The only benefi t was an

increase in winter sports such as ice skating. (Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art

Resource, NY)

Clocks

139

may have been a global or hemispheric cooling trend already beginning, and

regional weather patterns may have shifted to an unstable system. High and

low air pressure zones over Iceland and the Azores islands became unsta-

ble, ocean currents shifted, and a long period of bad weather settled over

Europe.

Between 1315 and 1322, most of Europe had too much rain and cold

winters. Harvests were fl ooded, and crops did not grow. There was mass

famine and death from starvation. During the 1320s and 1330s, the win-

ters were on average much colder than in the previous century, although

the rains moderated and crops grew. In the 15th century, the climate was

somewhat warmer, but it did not warm much by 12th-century standards.

Although the average temperatures only shifted by one or two degrees

Celsius, the effect on society was dramatic. In many parts of Europe, winter

had been a cold, rainy season during the Medieval Warm Period. During the

Little Ice Age, it became a time of heavy snow, bitter cold, frostbite, and

death. Those who could get enough to eat and keep warm could enjoy win-

ter sports such as sledding and ice skating, since the rivers now froze. The

poor died of malnutrition and cold.

Glaciers in the Alps, and in Norway and Iceland, continued to grow into

valleys and across roads, reaching their peak sizes around 1700. Periodic

famines continued; by the 16th century, thousands of villages and farms had

been abandoned. Higher elevations were no longer habitable, and many

people had died from famine, plague, or war. Families crowded together,

and near towns, for survival. The Little Ice Age tapered off after 1900 as

temperatures and sea level rose and glaciers receded.

See also: Agriculture, Fishing, Forests, Records.

Further Reading

Fagan, Brian. The Great Warming: Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civi-

lizations. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

Fagan, Brian. The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History, 1300–1850. New

York: Basic Books, 2001.

Ladurie, E. LeRoy. Times of Feast and Times of Famine: A History of Climate

Change since the Year 1000. New York: Doubleday, 1971.

Clocks

In the era before mechanical clocks, time was envisioned as a fraction of

the period between sunrise and sunset. Accuracy was not important; it was

enough to say that something happened in the fi rst period after sunrise or at

the noon hours. Time at night was marked by the setting of stars so people

who shared turns keeping watch could divide the time fairly.