Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Clocks

140

Sundial clocks had been used since antiquity, from small sundials attached

to walls to large megaliths like Stonehenge. There was no standard way to

divide time, and every sundial could follow its own marks. The Romans and

Jews divided the daylight hours into 12, but the Anglo-Saxons divided the

day into four tides. Since daylight periods in the North varied by season, the

exact length of an hour also varied. Hours were different at other latitudes.

What mattered was not the length of the time period but its position in the

day. These variable hours are called temporal hours.

Monasteries marked hours for prayer, with no need for any other times.

Sunrise, approximately six in the morning, was called prime in Latin. At

about nine, it was three hours later, and so was called tierce. Noon was

six hours after sunrise, so it was sixt. At three in the afternoon, it was nine

hours after sunrise, or nones. The prayer times multiplied after that until they

also included matins at midnight, lauds at dawn, and vespers and compline

in the evening. These times were approximate and were marked by the ring-

ing of a bell.

Sun and Water Clocks

Parish churches in medieval Europe used sundials to mark the times of

their services. Each sundial had to be made individually for the place and lati-

tude, and some were very simple. Some are known as scratch clocks because

they were literally drawn onto the wall of the church. Each parish priest

could mark the hours as he wished, since they only needed to coordinate

time in the village, not the outside world. Accurate equal-hours sundials were

not invented until the close of the Middle Ages. They required the gnomon

of the pointer to match the tilt of the earth’s axis, which required calcula-

tions of position using an astrolabe. The earliest known sundial of this type

was made around 1450.

Approximate division of time was not always good enough. The biogra-

pher of Anglo-Saxon king Alfred the Great wrote that he invented the fi rst

candle-clock around the year 886. The king wanted a clock to help him di-

vide his time between his royal duties and studying so that he would not fa-

vor either task. The candles had to be made to a precision size so they would

burn exactly three inches per hour. The king kept them in a transparent

horn lantern. However, because beeswax was expensive, this system was

only fi t for a king.

The development of sand hourglasses is unclear in history. The earliest

illustration showing an hourglass is in an Italian fresco from the 14th cen-

tury; their use before this time has often been assumed, but they may have

been a new invention in the 13th or 14th century. Two blown- glass bulbs

were connected by a neck with a diaphragm inside to keep their contents

separate. The diaphragm had a carefully calibrated hole to allow the sand

Clocks

141

or pulverized eggshell to fl ow from one bulb to the other. They were set to

last one hour and were used in manufacturing processes that needed to be

timed, on church pulpits to time one-hour sermons, and at sea, where the

pitching of the ship did not alter the sand’s fl ow.

Water clocks preceded mechanical clocks. Greek engineers had devised a

water clock called the clepsydra that used gears or a pulley to raise a pointer

as water fl owed into a reservoir. Romans used clepsydra to time speeches in

the Senate or in court but did not use them at home or as continual public

clocks. Water clocks did not work without being carefully tended. A man had

to pour water into them at the right times to keep the infl ow reservoir full.

In the Middle Ages, Greek and Roman water-clock technology passed via

Constantinople to Arabic scholars. After studying the ancients and writing

treatises on hydraulics, Arabic clock makers were able to produce pieces of

engineering that astonished Europeans. Caliph Haroun al-Rashid sent a

water clock to Charlemagne that used dropping brass balls to trigger its time-

telling mechanism. At noon, 12 brass horsemen emerged from windows, like

the cuckoos in later mechanical clocks. The same Baghdad engineer made

an even grander clock for the caliph and illustrated its workings in a book.

It was a true automaton in which falling water drove different moving parts.

Sitting on an elephant’s back, a mahout, a tall howdah, and a writer sitting

in the howdah all moved to keep time. At half-hour marks, an eagle dropped

a ball into a dragon’s mouth, and the dragon dropped the ball to ring a cym-

bal while the mahout hit the elephant’s head.

In Muslim Spain, water-clock technology developed to where some pri-

vate homes had ornate water clocks. Arabic works on engineering were trans-

lated into Latin in the 13th century, at which point the scholars of Europe

could learn the details of time-keeping science. Even before this, based on

the Roman traditions and their own inventiveness, Europeans had been

making less elaborate water clocks.

In medieval Europe, monasteries were the chief builders of water clocks

because they wanted bells to chime at hours for prayer. They called their

clock the horlogium, or, later, the horloge. The name meant a timekeeper,

not specifi cally a water clock, so when mechanical clocks came into use, they

shared the same name. Monasteries had sundials, too, but only the horlo-

gium could tell time in the dark. It could keep equal hours year-round, even

in winter, if the water could be kept from freezing. The horlogium had

another advantage because its motion was truly mechanical and could be

designed to make sounds, not just a moving shadow. It kept exact hours,

rather than temporal hours.

Some may have been room sized and others smaller. A larger water res-

ervoir allowed the clock to run longer without needing to be refi lled by a

human operator. In a monastery, the horlogium needed to run at least

three hours between settings. In 1198, the horlogium saved the precious

Clocks

142

relics at the monastery of Bury Saint Edmunds. The bells rang to wake the

monks, who discovered the reliquary’s table on fi re. They used some of the

horlogium’s reservoir water to douse the fl ames. Clearly, the monastery’s

clock contained a fair amount of water in its tanks.

There are only a few existing drawings of these clocks, so modern schol-

ars cannot be sure how they worked. Some may have worked by releasing

weights as the water level dropped; the weights could have rolled down to

ring bells. Some may have had a wheel with reservoirs that slowly fi lled and

suddenly dumped. Pins attached to the wheel, as to a roulette wheel, would

trip bell-ringing mechanisms.

Mechanical Clocks

The fi rst entirely mechanical clocks were not intended to mark hours.

They were based on astrolabes and armillary spheres, astronomical models

to predict the movements of the planets. Medieval astronomers had a me-

chanical view of planetary motion, envisioning the planets as fi xed on com-

plex combinations of circles. It was appealing to apply new engineering

technology to the astronomical model and produce a machine that predicted

the rising and setting of stars, the phases of the moon, and other heavenly

events. A good astronomical clock of the mid-14th century could use the

moon’s phases to predict the date of Easter and other movable feasts. Mark-

ing off 24 equal hours in a day was an afterthought.

The grandest astronomical clock in medieval Europe was built by

Giovanni Dondi of Padua around 1350. His father had also made astronomi-

cal clocks, so the craft reached its peak in the family. The clock tracked fi ve

planets, the sun, and the moon and was driven by falling weights. There are

no records to show when the fi rst clock was built, either for astronomy or

for keeping hours, but Dondi’s notes refer to the clock’s parts as commonly

known mechanisms. He seems to have built his masterpiece in a time when

simpler clocks were being built, even if few records were left concerning

these clocks.

In a time when many other records were kept copiously, we know little

about when churches or towns installed clocks or who made them. Dates

were rarely put on clocks, and those that have dates may indicate repairs or

replacement of parts, not the original installation. The fi rst public clock

for daily hours may have been the city clock in Paris, built in 1300. King

Charles V of France built three public clocks in Paris and ordered the churches

to ring their bells when the clocks struck. By 1335, Milan had a clock that

struck a bell to ring the hours. Other major Italian cities, such as Florence,

Genoa, and Bologna, built clocks in the following decades. Strasbourg,

Germany, had a clock by 1354. English priories and churches may have in-

stalled clocks beginning around 1280, but by the middle of the 14th cen-

Clocks

143

tury, like the rest of medieval Europe, England’s churches had mechanical

clocks. Barcelona installed a public clock in 1392. By the end of the 14th cen-

tury, town clocks were a symbol of success and modernity.

The fi rst mechanical clock makers were skilled blacksmiths and lock-

smiths. Clock making gradually became its own craft, and, by the end of the

Middle Ages, it was an established guild. Churches and towns also needed

clock keepers to tend these machines all day, moving weights and adjust-

ing the parts.

A falling weight, usually a large stone, was the power supply substituted

for water. Weights could also be made of lead, and sometimes they were cast

with a pin to hold a pulley for the rope to pass through. One reason clocks

were often mounted on towers is that the weight needed a long way to drop

before it was wound again. In the earliest clocks, the mechanism was on the

ground fl oor, and the tower’s height carried the ropes to a pulley at the top.

Later clocks were placed at the top with the weights falling below them.

The clock’s mechanism was housed in an iron framework, often a large

cube. The iron was hand-forged wrought iron hammered out by a smith.

Screws and bolts were not invented until around 1500, so the frame was

put together with pins tightly driven into holes. A very thick wooden axle,

called a barrel, wound a long rope with the weight on the end. Left to fall

freely, the weight would unwind the rope, spinning the axle very fast, but

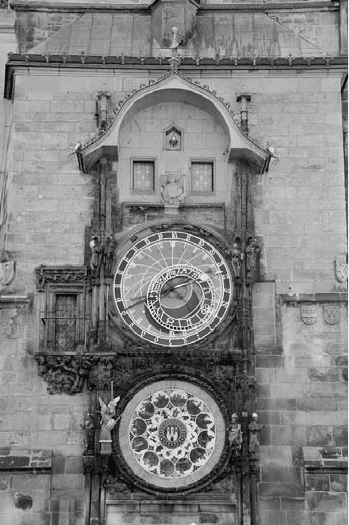

Early mechanical clocks were not

designed for anything as dull as telling

hourly time. They were complicated

astronomical timekeepers that tracked

the moon and planets. Astronomical

time meant more to medieval people

than clock time until late in the 14th

century. Even then, astronomical clocks

seemed nobler than simple hour clocks.

Perhaps this is why the city of Prague

chose to go to the great expense of

adding one to the city hall as late as

1410, when many other European

cities had hour clocks. (Vladimir Babic/

Dreamstime.com)

Clocks

144

the weight’s motion was slowed and regulated, and the axle moved with

steady, deliberate speed. It was the driver for a series of gears and wheels made

with precision to turn the axle’s rotational speed into timekeeping.

The chief engineering problem that faced clock makers was how to drive

a mechanism with falling weights yet keep its motion steadily regulated.

The invention of the escapement solved this problem. In purest form, in a

pendulum clock, two types of motion interact. A falling weight pulls a circu-

lar gear to turn, while a swinging pendulum permits the escapement to twitch

left and right. The escapement can either stop the gear from turning or

swing away to permit it to turn. The swinging pendulum moves the escape-

ment back and forth, permitting the gear to turn by little jumps as the weight

pulls on it.

In the Middle Ages, though, the escapement was not yet driven by a pen-

dulum. Medieval clocks used a mechanism called a verge escapement. At one

end of the main drive axle, there was a gear shaped like a crown with saw teeth.

It was positioned next to a large pin, called the verge, that had two special

features. It had a horizontal crossbar called a foliot that carried weights; it

could be made heavier to provide greater resistance to slow the mechanism

(or could be made lighter to speed it up). At the point where the crown

touched the verge, two pallets met the crown’s teeth, stopping the crown

wheel from turning. The turning saw teeth pushed each pallet out of the way

before catching them again. Since the pallets were turned at nearly right an-

gles to each other, they took turns being caught and pushed, and, as each

was engaged by the crown’s teeth, the verge turned a bit, then back the other

way, then back again. The turning motion of the crown wheel became os-

cillating motion in the verge and foliot. The crown wheel’s turning was

stopped and released, repeatedly, which regulated how quickly it could turn.

The accuracy of the clock depended on how well the verge and foliot were

able to make the crown wheel turn with precise speed.

Clock makers experimented with escapement and striking mechanisms.

A foliot bar hung with multiple weights could have its weights moved to

different positions to change its balance and drive the clock faster or slower.

A locking plate, or count wheel, made the clock strike a different number

of bells for each time. It turned slowly, once every 12 hours, and had

notches cut in its perimeter. An arm attached to the striking device would

allow striking until it fell into a notch. The notches were cut with increasing

distance between them to permit the clock to strike more times each hour

as the day passed. This was one of the earliest inventions of machine memory.

The fi rst town clocks did not have faces. Because of the monastic tradi-

tion of ringing bells for prayer hours and the city watchmen’s tradition of

ringing a bell at certain times, the medieval concept of a time-keeping device

was auditory, not visual. Bell ringing was the entire purpose of the clock. In

a city, the clock was also a luxury toy that put on a show for the taxpayers.

Clocks

145

The clocks drove automata in which mechanical fi gures played music or

moved to announce each hour. In many cases, a wooden man-at-arms called

a jack moved his arm to strike a bell. Some towns named their clock’s jack

with names like Jack the Smiter. (The wildfl ower jack-in-the-pulpit is named

for this kind of jack.) Many later medieval clocks had automata that did

more than ring bells. In the clock at Wells Cathedral, in England, four

knights tilted at the joust, and one was unhorsed. In the Strasbourg Cathe-

dral clock, the 12 disciples circled around Jesus.

Clocks became regulators for commercial time, not church time. Town

watchmen used the clock to know when to cry the hours or ring bells. No-

taries began to write down the time of day when a document was created,

not just the date. Towns set curfews and regulated working hours for cer-

tain noisy crafts by clock time. Courts and assemblies set meetings by clock

time, which permitted them to set time limits and fi nes for tardiness. As com-

merce got used to regulating meetings and other activities with precision,

wealthy men wanted clocks at home. It was not enough for a clock to drive

a set of bells to ring hours for prayer. People needed to see time and have ac-

cess to timekeeping at home.

The concept of a visual clock face came at the end of the Middle Ages.

The astrolabe’s face, divided into the hours and minutes of a 360-degree

circle, became the model for the development of a clock face. The astrolabe

had a movable hand, the calculer, that worked as a pointer. In the 14th and

15th centuries, some clock makers adapted the astrolabe’s face and pointer

to the calculation of time. Mechanized and adapted, it became the clock

face. Town and church clocks had dials installed after 1400.

At the very end of the Middle Ages, some new clocks were driven by

coiled springs. The earliest manufacturing record of spring-driven clocks

is in Burgundy around 1430, and there is one existing clock from around

1450 in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The spring was coiled

inside a drum, and it was wound up and then unwound slowly. Although

the spring was more convenient than weights, it was harder to regulate. A

spring’s force is always greatest at fi rst, and then peters out, unlike gravity’s

steady pull on a weight. One simple solution was to set the spring’s force to

unwind a string from a spindle and to shape the spindle like a fl ared cone or

a trumpet’s bell. This spindle was called a fusée, and it was the main drive

axle of the clock. Its unconventional shape provided more resistance when

the spring’s force was greatest, but, when the spring’s power was running

down, it unwound string more easily. This balance kept the clock’s motion

steady.

Early spring-driven clocks are large instruments that stood on the fl oor

or sat on a table. An iron or brass frame held the moving parts and stood on

legs. The frame was always ornate because the clock was a very expensive

luxury item. After a medieval craftsman had put so much effort into the

Cloth

146

precise handmade gears, he did not consider his work complete until its case

was decorated as though it were a tiny Gothic cathedral.

See also: Astrolabe, Bells, Machines, Monasteries.

Further Reading

Beeson, C.F.C. English Church Clocks 1280–1850. London: Brant Wright Associ-

ates, 1977.

Bruton, Eric. The History of Clocks and Watches. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books,

2004.

Cardwell, Donald. Wheels, Clocks, and Rockets: A History of Technology. New York:

W. W. Norton, 2001.

Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard. History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal

Orders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Frugoni, Chiara. Books, Banks, Buttons, and Other Inventions from the Middle Ages.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2003

Gimpel, Jean. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages.

New York: Penguin Books, 1977.

Rock, Hugh. Church Clocks. Botley, UK: Shire Publications, 2008.

Cloth

The basis of all cloth making is the creation of thread, from which cloth is

woven. All materials—cotton, linen, wool, and silk—require the natural

fi bers to be twisted into a uniform thread. The most common thread in Eu-

rope’s Middle Ages was of wool, and it was most easily spun by hand with a

distaff. Flax, the second most common material, could also be spun easily

by hand. All women, rich and poor, spun, and, in order to produce the vol-

umes of thread required to clothe a household, they spun nearly all the

time. Medieval images of women show them holding spinning materials

while traveling, feeding animals, and cooking. Many also wove, but weaving

and other stages of cloth production were increasingly part of a skilled pro-

fession.

After the year 1000, some areas became centers of cloth manufacture.

Flanders had climate conditions that were good for growing dye plants,

and its soil had the right kind of soil for fulling, a cloth-fi nishing process. It

was close to England, which exported large amounts of wool. The weaving

industry of Flanders became one of the hubs of European trade; silk mer-

chants traveled from the Mediterranean to trade for Flemish woolen cloth

woven from English wool. During the early 14th century, the English in-

duced some Flemish weavers to move during a period of political instability

in Flanders. By the close of the Middle Ages, England was also a wool-

weaving powerhouse. Italy produced most silk, and it also wove the newest

Cloth

147

textile fi ber—imported cotton from Egypt and India. There were also nov-

elty fabrics: nets, felt, and ribbons.

Four Fibers: Wool, Flax, Silk, and Cotton

Wool was medieval England’s chief export, and large fl ocks of sheep were

also grazed across France. Monasteries kept the largest fl ocks of sheep;

they used the sale of wool to fund their communities. Cistercian monaster-

ies were especially methodical in their sheep breeding and shearing. They

graded it by quality and sold it in bales.

The best wool came from Merino sheep imported from Spain, the worst

from more primitive double-coated sheep. On each sheep, the fl eece’s qual-

ity varied. Fleece from the sheep’s shoulders was the best, while belly fl eece

was not usable. Sheep breeders kept mostly white sheep but often kept some

black or dark brown sheep in the fl ock for color variation. These alternative

colors could be woven into stripes or spun into a blended shade.

Wool was fi rst washed and then combed or carded to remove brambles

and lengthen the fi bers. In the early Middle Ages, wool was combed with a

pair of wool combs that had a few rows of bone or metal teeth. They were

usually heated and dipped in fat, and then one was placed on a post. The

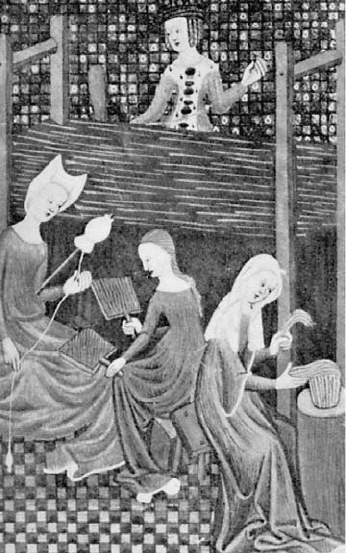

Especially in a large, wealthy household,

the women and girls were constantly

working to produce thread. Here, the

young girl on the right is combing wool

to clean it. The cleaned wool goes next

to the girl in the center, who is carding

it to make the fi bers lie smooth. Her

carded wool is rolled and given to the

spinner on the left. She ties the rolled

wool onto the distaff, which she holds

under her arm. Her hands are free to

draw and twist the wool into thread.

The spindle at her side is a spinning

weight for tension and twist. The

aristocratic lady who presides may be

embroidering. (George Unwin, Gilds

and Companies of London, 1908)

Cloth

148

other comb was held. A mass of wool was put onto the stationary comb,

and the other comb drew the wool fi bers from it. The wool was repeatedly

combed until its fi bers were as long as possible and ready to be spun. Carding

was introduced to the wool industry as a solution for how to use wool with

short fi bers. The card was a board covered with leather and densely packed

with small iron hooks. Like combs, cards worked in pairs and had to be

oiled. Short-fi ber wool was repeatedly raked between them.

Wool was the all-purpose European textile fi ber. It was the chief fabric

used for all outer clothing and blankets. It was the yarn woven into tapes-

tries, and it was often the thread used in embroidery. It could be tightly

fulled and made windproof or left unfulled so it would be fi ner and more

fl exible for a lady’s dress. It was woven thickly to make blankets and woven

thinner to make hose. It was rarely washed, if ever.

Flax was the earliest plant used to make textiles. It is a fi eld plant that

bears small blue fl owers, and it grew in nearly every European climate, so its

production and use were universal. The stem of the fl ax plant, soaked until

it rots, separates into many fi ne fi bers that run the length of the stem, from

root to tip. It must be soaked for about two weeks to begin rotting (a process

called retting) and then dried, beaten, and scratched to remove the fi bers

from the rotted bark. In the 14th century, a new technique for handling fl ax

improved linen production. This was the fl ax breaker, a simple hinged set

of boards that bent and beat the fl ax fi bers. It processed them faster than

pounding with hammers, and it could be mechanized with a water mill.

The fl ax fi bers were separated into short ones that made tow, which was

coarse and cheap, and long fi bers, which were spun into real linen. Flax fi -

bers were not elastic like wool, and they were harder to spin and weave.

Linen was used for sheets, towels, shirts, and undergarments. It was usu-

ally bleached or left its natural color because linen did not take dyes as

readily as wool. It held up through repeated washings, so it was used for gar-

ments most likely to be boiled, soaped, or beaten. When fl ax was woven into

towels, the type of weave chosen left some fl oating weft threads that made

the cloth more absorbent. The modern word diaper for an absorbent cloth

used with babies fi rst applied to cloth woven in a repeating pattern of

goose-eye diamonds that left these fl oating threads. In the Middle Ages, di-

aper meant a repeating pattern and could describe the background of a

shield or the design on a castle wall.

Silk came from China, where the secrets of raising silkworms on mul-

berry trees and weaving their delicate threads were closely guarded. Draw-

looms were making patterned silk brocades in China while Europeans were

still weaving on simple vertical looms. Silkworms were also native to India,

and they spread from there to the Arab countries. Muslim rules against

pride at fi rst discouraged the use of silk, but a major silk-weaving industry

grew in Persia. Chinese and Persian silks were patterned with designs that

Cloth

149

looked very foreign to Europeans, whose royalty treasured them for funeral

shrouds and robes. Saint Cuthbert, an Anglo-Saxon monk of the seventh

century, was buried in a shroud of imported silk.

The trading route from the Mediterranean Sea to China was known as

the Silk Road because silk was its primary import, and all silk came from the

East. Even when the Byzantine Empire set up silk-weaving centers in Alex-

andria and Constantinople, the silk itself had to be imported. Legend says

that two monks smuggled some silkworms to Constantinople during the

sixth century. By the ninth century, Byzantine silk weavers had their own

supply of raw silk. Access to the expensive purple dye made from mollusks

in Lebanon meant they could produce the most expensive silks of all.

Constantinople guarded the secret of the silkworms as China had done.

However, gradually the technology spread from Persia. It came fi rst to Arab-

ruled Sicily and Spain, which established mulberry orchards and by the

10th century were producing raw silk. Spanish silk was perfected in the Al-

meria region; by the later Middle Ages, its weavers made lampas and damask

with geometric designs. From Sicily, Jewish silk weavers brought the tech-

nology to the Italian city of Lucca, which developed the industry to a new

level. Like silk-weaving centers before them, the Lucchese made it a capital

offense for silk workers to leave the city, but the city was sacked by Pisa in

1314, and silk workers fl ed to Florence and Venice. Silk-weaving technology

did not reach Northern Europe until the late Middle Ages, but then towns

like Arras and Beaumont became centers of silk weaving using raw silk im-

ported from the Mediterranean region.

Silk mills used waterpower to spin the silk threads together into stronger

strands for weaving. Waterpower was used for silk, but not for wool, be-

cause human labor for wool was still cheaper and because the speed and

power of water was not needed to spin wool as it was to spin silk.

New fabrics came from the silk industry. Brocade was a fi ne silk fabric with

dense, complex patterns woven onto it with a separate shuttle and often in

another color; invented in China, the technique spread through Persia and

into Europe. Satin was a very dense, thick silk, also developed in China;

damask was a heavily patterned silk fabric fi rst made in Damascus. Damask

weaving required well-developed drawloom technology to produce compli-

cated repeating pictures of heraldic designs, animals, and fl owers. Damasks

produced in Italy, and sold all over Europe, combined artistic infl uences of

China, Arabia, and Europe. A typical damask might have peacocks, lions,

monkeys, or faux-Arabic letters.

Extremely lightweight silk crepe came from the East during the Cru-

sader era and was used to make fancy, lightweight pleated dresses for noble-

women. Later, silk crepe, often with a border stripe, formed the fl oating

veils of 14th- and 15th-century headdresses. Shot silk was woven in two col-

ors; from Baghdad came baudekyn, a shot silk with threads of gold.