Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Hood, Robin

350

a general word in medieval Italian to mean the prize for a civic horse race

and then the race itself. Bologna held its palio race on Saint Peter’s Day

with a bolt of scarlet cloth as the prize. Other Italian towns repeated these

customs, with candle processions and horse races, as they could afford.

Midsummer was also a folk festival for most Northern Europeans. It

was Saint John’s Day, but the summer solstice in the middle of July was the

original pagan festival. Pagans had made bonfi res of bones and leaped

through the fl ames for luck. As Christians, they still made bonfi res, and some

threw oak branches and fl owers into the fi re with folk rhymes based in

pagan beliefs. The traditional rhyme in England ran, “Green is gold. Fire is

wet. Fortune’s told. Dragon’s met.” In some regions, they fl oated small fi res

or candles on water. Mumming plays about Saint George and the dragon

were popular.

Saint Swithin’s Day in England was also in July, and it had traditions of

strewing fl owers and making garlands to wear and with which to decorate

the church. The weather on Saint Swithin’s Day was supposed to predict

the coming summer weather. In England, Lammas Day came in August and

was a day to celebrate the harvest. Sheep were permitted to graze freely on

village lands that were normally fenced off. Lammas came from the Old

English word for “loaf.” On that day, people made loaves of all kinds, from

currant buns to fanciful breads with edible fl owers.

See also: Calendar, Dance, Drama, Feasts, Robin Hood, Music.

Further Reading

Cosman, Madeleine Pelner. Medieval Holidays and Festivals. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

Davidson, Audrey Eckdahl. Holy Week and Easter Ceremonies and Dramas from

Medieval Sweden. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1990.

Diehl, Daniel, and Mark Donnelly. Medieval Celebrations. Mechanicsburg, PA:

Stackpole Books, 2001.

Innes, Miranda, and Clay Perry. Medieval Flowers: The History of Medieval Flowers

and How to Grow Them Today. London: Kyle Cathie, 2002.

Jackson, Sophie. The Medieval Christmas. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2005.

Reeves, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

Sheingorn, Pamela. The Easter Sepulchre in England. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval In-

stitute Publications, 1987.

Hood, Robin

Robin Hood was the most popular English folk hero of the 14th and 15th

centuries. His legends were restricted to England, and, although they may

Hood, Robin

351

have been sung in courts, they belonged to the common people in a way

King Arthur did not. Like the Arthurian cycle, stories of Robin Hood were

invented by different people in different times and were only united into a

single strand during the 15th century. The Gest of Robyn Hode connected

fi ve existing stories, patching them together as a complete story that ended

with the hero’s death. There are at least three other contemporary 15th-

century stories, as well as later stories composed in the 16th century. But

Robin Hood seems well established as a folk hero of ballads long before.

The 14th-century poem “Piers Plowman” criticized priests who knew the

stories of Robin Hood better than their prayers, and there are scattered ref-

erences to May plays about Robin.

Historians have tried to identify an original Robin Hood, but it is most

likely that his name was something like the modern generic name John Doe

and that his literary character has a reality similar to Batman’s. Earliest ref-

erences to Robin place him in the 13th century, a time when hoods were

a universal hat fashion. There were other outlaws in stories, chiefl y Adam

Bell, Clim of the Clough, William of Cloudesly, and Gamelyn. Their stories

are very similar to Robin’s. All take refuge in the forest, all are guilty of

poaching deer, all get drawn out of hiding by treachery and must use their

wits and their weapons to regain safety, and all fi nd ultimate justice with the

king, not with his offi cers. That Robin Hood’s stories gained dominance

may be an accident of his name working best in rhyme and song.

The context for Robin and the other outlaws is the restrictive forest laws

laid down by King William I and his descendants. These laws were at the

peak during the reign of Henry II in the 12th century. Henry II’s sons ap-

propriated more forest lands. King John, the villain of the modern Robin

Hood legends, was only following the precedents of his father and older

brother Richard I in adding to his forest preserves. His son, Henry III, was

required to promise to uphold the Magna Carta provisions that King John

had signed unwillingly; from then on, the royal forests began to shrink, and

poaching was a less serious offense. Other aristocrats began to keep forests

and parks, though, and they hired foresters and parkers to police them.

The Robin Hood ballads show familiarity with hunting practices and

terminology. The stories accurately differentiate between the types of deer

in medieval English forests and use clever references to hunting customs.

Robin often met his men under a designated tree—the trystel, or trysting,

tree. In bow hunting, when the deer were driven toward the hidden royal

hunters, the place where they hid was the tryst. Robin and his men were

not aristocratic hunters with dogs. They used the bow, the weapon of the

common folk. By the 15th century, landowners were more concerned with

woodcutting and unauthorized grazing than with poaching. Poaching still

occurred, but it was infrequently prosecuted, and the punishments were

not worse than fi nes. Some records show a fair number of respectable

Hood, Robin

352

citizens venturing into the forest to bring home a hart or buck, probably

with bows as Robin and his men did.

The Robin Hood of later stories, depicted in modern fi lm versions, is

a dispossessed nobleman living in the time of King Richard I and Prince

John. The medieval Robin is a yeoman of the 15th century with stories that

include King Edward, not King Richard. King Edward I was a popular king

known for relatively good governance, and his reign was in the late 13th

century. The forest laws did not press on people as much then, and travel

and trade were expanding. The Robin Hood stories are more comfortably

set in the reigns of the kings Edward I, II, or III than in the time of King

Richard I.

Although the Robin Hood stories about the 13th century were written

down only 200 years later, there is already some anachronism. The term yeo-

man was not common in the 13th century, but it was widely in use by the

The cast of Robin Hood’s tales grew until the stories reached a sophisticated form in

the 19th-century version by Howard Pyle. Fashions and customs of the 14th century

were enshrined in Robin’s stories so that many modern readers and moviegoers

associate hoods, short coats, and hose only with Robin Hood. (Howard Pyle, The

Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, 1890)

Hood, Robin

353

15th. It was in such wide use that it is not clear what a yeoman really was.

Yeomen were small but independent farmers, and they were also middle-

ranked servants of the king. In the context of the forest laws, a yeoman

could be any sort of royal offi cial guarding the deer and trees. The word

may have had such wide use because the old terms didn’t fi t as societal

structure shifted. Yeoman may have indicated a general middle-class posi-

tion. The medieval Robin Hood was not a nobleman; he was a middle-class

Everyman.

The sheriff, Robin’s main adversary, was a more important fi gure in the

13th century than in the 15th. Sheriffs were appointed offi cials who admin-

istered justice in the king’s name for a term of one year. Local landowners,

the small nobility and knights, took turns as sheriff. They collected some

taxes, held inquests, and presided over courts, while also being responsible

for making arrests and holding men for trial. In the 12th century, sheriffs

had been appointed directly by kings and had power unchecked by the peo-

ple; their appointment from among the local landowners kept them respon-

sive to the community. Even with decreased power, they oversaw enough

facets of local government to tempt them to use their term for corrupt

gain. They could sell jobs like “under sheriff” for high fees, and many took

bribes. Sheriffs were not popular among the common people, and a legend-

ary Sheriff of Nottingham made a good target for comic stories.

Robin Hood also frequently found himself up against wealthy monks.

The stories make it clear that Robin himself was very devout, probably more

than the greedy monks. By the 15th century, half of England’s land was

owned by the Catholic Church, often by monasteries. While some monks

were still devoted to the care of the poor and to prayer, many had become

businessmen who managed farms and mines and collected rent from ten-

ants. They were not responsible to civil law, and the people resented their

greed in the name of religion. When Robin Hood robbed a rich abbot, his

audience could only cheer.

Robin’s band grew as the stories expanded. Friar Tuck was a late addi-

tion, but Little John was already his lieutenant in 14th-century references.

Much the Miller’s Son and Will Scarlet are two other early names in the

band, which mostly remain anonymous. Robin’s lady, Marian, was the last

addition. In the Gest of Robyn Hode, there is no Marian. Robin’s devotion is

for the Virgin Mary, and he is as single and chaste as a monk. Marian seems

to have been added in folk dramas about Robin Hood that were acted in

villages and towns for May Day. Robin and forest freedom were celebrated

on this spring day, but so were pretty girls with garlands. May Day plays

were very often about Robin, and they needed a pretty girl, Marian. After

the Reformation brought an end to the public cult of the Virgin Mary,

Robin’s stories may have been edited to place a real woman, Marian, in the

spotlight instead.

Horses

354

The medieval Robin Hood did not rob the rich and give to the poor. He

robbed rich travelers, especially if they were corrupt. He always invited them

to dine, fi rst, in his role as king of Sherwood Forest. Travelers were asked

to pay for their dinners, which was the robbery. In the legends, an honor-

able man who could not pay was not further harassed. Robin helped a poor

knight with a loan, but he wanted it repaid. The charitable Robin who gave

to poor peasants was a later invention.

See also: Drama, Forests, Holidays, Hunting, Monasteries.

Further Reading

Holt, J. C. Robin Hood. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

Knight, Stephen. Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press, 2009.

Pollard, A. J. Imagining Robin Hood. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Horses

With the fall of the Roman Empire, the horse as a war animal lost its im-

portance for a few centuries. Invasions of mounted Arabs, Huns, and Turks

pressed Europeans to learn cavalry warfare. With horses came the most fa-

miliar fi gure of the Middle Ages: the knight. At the same time, improve-

ments in peacetime horse care made all kinds of horses more important to

the economy.

Europe had herds of ponies and small horses when it was part of the

Roman Empire. Cold regions had smaller ponies with thicker hair. Cool,

wet regions tended to raise horses with larger bones and heavy muscle. Hot,

dry regions favored horses with thin, dense bones; light bodies; and short

hair. These ponies carried packs and, in some places, drew two-wheeled carts.

Horses are different from ponies in more than size alone. Even small

horses, brought into Europe from North Africa and Asia, were able to breed

larger horses when their diet improved. The average horse in medieval Eu-

rope would be considered small today. (Horses are measured to the top of

a shoulder, called the withers. One hand equals four inches.) A typical mod-

ern horse is about 15 hands high, while a modern pony is typically be-

tween 12 and 13 hands. Most medieval horses were more nearly pony sized.

Their “great horse” for war was the size of an average modern horse.

Providing horses for war and civil use was a constant endeavor. A mare

can produce no more than one foal per year, and often less. There was grow-

ing demand for horses as both warfare and agriculture in Europe came to

depend on them. The old methods of keeping a herd of horses to breed un-

directed were not good enough, and, by the close of the Middle Ages, Eu-

rope had many aggressive breeding programs and an international market.

Horses

355

Horses in War

Byzantine troops depended heavily on mounted archers, who also car-

ried spears and a sword. They could use lassos, as could other Eastern caval-

rymen, and they occasionally used them as weapons. Byzantine cavalrymen

fought in a unit and were trained to stay together in ranks. They were a

fi ghting unit, not individual knights.

The western Germanic tribes—the Franks and Anglo-Saxons—had no

tradition of fi ghting on horseback. The eastern Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Van-

dals, and Lombards did, but they did not combine cavalry with bows. Avars,

Turks, Mongols, and Magyars, invaders from Asia, all rode small horses and

were able to shoot arrows on horseback.

The fi rst Muslim armies were cavalry and rode both camels and horses.

Some did not use saddles, and they did not adopt stirrups at fi rst. By the ninth

century, after taking over Byzantine and Persian territories, they were using

both wooden and iron stirrups. They fought with bows, but also with long

spears. Arab horses were famous for their small size and great speed. The

Arabs called them Faras and kept their breeding separate from the Barb

horses of North Africa. The Muslim conquest of Spain was mostly carried

out by North African Berbers commanded by Arab generals. They brought

their Barb horses and also used the existing strains of horses in Spain, now

called the Andalusian breed. They were larger than true Arab horses. Mus-

lim emirs and caliphs in Spain used selective breeding to blend Spanish and

North African horses.

After Charles Martel’s heavy infantry defeated Arab cavalry at the Battle

of Poitiers, the Franks began to use mounted warriors. The Avars, invading

from the East, were defeated in 976, and the Franks adopted their use of

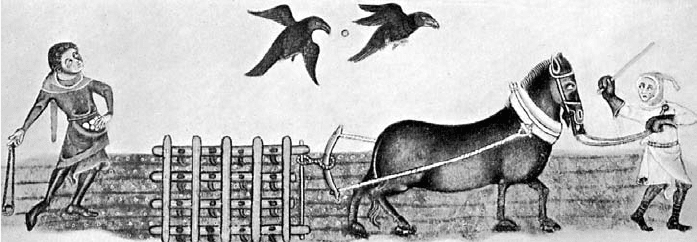

The horse’s earliest farm use was in pulling lighter equipment such as the harrow. In

this 14th-century pictures, a horse-drawn harrow is covering the seeds as the sower

casts them out with his hand. The farmers carry sticks to chase away large, aggressive

crows. The horse’s harness is very simple: the harrow is tied to ropes on the horse’s

collar. As harnessing grew more sophisticated, horse teams could pull heavy plows

and wagons. (The Print Collector/StockphotoPro)

Horses

356

stirrups. They did not develop methods of horseback archery and instead

trained to charge with lances and fi ght with swords on horseback. Their

horses may have been mostly purchased from Spain, since later Charle-

magne sent “Spanish” horses to the caliph of Baghdad as a gift.

The Franks also learned to hunt on horseback. Charlemagne spent many

hours on horses every day, both hunting and training for war. He required

horses as part of the taxation of his nobles; his royal farms carried out

breeding programs. Each stallion had a small herd of mares, but they were

rotated out to other herds to prevent inbreeding. Inferior horses spread

into civil society as riding horses and packhorses. Unlike later Christian Eu-

ropeans, the Franks had no taboo against eating old horses.

More horse-based invaders came into Europe. Magyars from Hungary

and Mongols from central Asia both used mounted warriors exclusively.

They traveled in horse-drawn wagons and lived in tents. Their ponies for-

aged on grass and did not need extra provisions, so both the Magyars and

the Mongols could travel faster than Frankish armies. Their ponies knew

how to dig for grass under the snow, while European horses did not. How-

ever, their style of horse warfare was better suited to the fl at grasslands of

central Asia. Western Europe was forested and did not have as much for-

aging pasturage. Even without military defeat, their onrush was slowed be-

cause their horses could not graze as they were used to once they left Asia.

Henry of Saxony became king of Germany in 919, during the invasions

of the Magyars. He built walled towns and trained a cavalry force that was

able to stop the invasion. The Magyars settled down as horse-breeders in

Hungary. The new Christian kingdom of Hungary continued to use light

cavalry with mounted archers, although they also adopted Western Europe’s

technology of heavy mounted knights. Hungary’s horse ways were no lon-

ger distinctively Asian.

During the 10th and 11th centuries, some Norman knights traveled to

Spain and fought against the Muslim armies as part of the Christian effort

to reconquer the peninsula. Some brought back Spanish stallions and used

them to improve Norman horses. By the 11th century, Normans were ex-

pert cavalry warriors. When the Normans invaded Anglo-Saxon England in

1066, they transported about 2,000 horses in open boats across the English

Channel. The Anglo-Saxons had horses, but they only used them for travel.

They fought on foot, using a shield wall. At fi rst, they were able to withstand

the Norman cavalry charge, but their shield wall broke after several charges

and retreats, and the Norman mounted soldiers ran them down. From

that time, mounted warfare was dominant in Europe until the era of gun-

powder.

The chief use for heavy warhorses was the chevauchée, a mass charge by

many knights in a line. Saddles for this tactic had rigid walls and essentially

locked the knight onto the horse’s back. The knight held a lance tucked

Horses

357

under his arm, reaching well in front of the horse. He could also fi ght with

his sword on horseback, but his lance was his primary weapon. The horse

was trained to charge into danger and to stop and turn quickly.

During the 12th century, selective breeding by kings and other wealthy

lords sought to create the best kind of warhorse. While size was an object,

overall strength mattered more. Once knights had been trained and armed

for horseback fi ghting, they were dependent on their mounts. If the horses

tired or could not carry them, they were more likely to be killed out from

under them, and a knight without a horse was not an effective fi ghter. A

knight whose leg was trapped by a fallen horse had to surrender.

In spite of selective breeding for size, knights’ horses were not large until

the 14th century. Most warhorses whose skeletons have been examined

were not taller than 14 or 15 hands. Modern racehorses are usually taller

than 15 hands, and modern draft horses are about 18 hands tall. A typical

14th-century knight stood shoulder to shoulder with his horse.

However, by the late Middle Ages, there was a distinctive type of horse—

the destrier, or “great horse”—for jousting. These horses were not large by

modern standards, but they were heavy and tall by medieval measure. They

were 15 or 16 hands, and they were heavily muscled so that they could

carry a great deal of weight for their size. Horses were expected to carry

not only their rider and his armor, but also their own armor. First it was

thick leather padding for the horse’s chest and head, and then steel plates.

The armor and the padded drapery, decorated with heraldic designs, were

called a caparison. The increase in padded horse armor then drove spurs to

greater size, since a horse protected from lances was also protected from his

own rider’s spurs.

Knights rode on palfreys or coursers to travel and had their destriers led

to spare their strength. Coursers were faster than warhorses, and they could

be mares or gelded horses. Destriers were always stallions, and they were

fi ery in temper and fantastically expensive compared to lesser horses. A war-

horse could cost more than a year’s income, but the horse for a servant, or

for an archer to ride on to move about from battle to battle, might cost less

than a tenth of a warhorse.

The Crusaders were heavily dependent on horses, both for travel and

for fi ghting. They shipped the horses in special transport ships that could

carry between 30 and 100 horses. The ship voyage across the Mediterra-

nean, which lasted more than two months, had to be broken into stages so

the horses could get fresh air and exercise on islands. Once in Palestine,

the horses had to be brought back to full strength after so much inactivity.

When they were injured or died in battle, it was diffi cult for the knights to

replace them, and some knights had to ride mules.

Crusading orders of knights like the Templars kept large stables of horses,

with all the supplies needed: farriers, harness makers, grooms, and large

Horses

358

supplies of hay and water. In addition to their destriers, Templars needed

palfreys to ride while traveling and rounceys for the servants or squires who

led the warhorses. All war undertakings required workhorses to carry equip-

ment and supplies. Crusaders were in constant need of buying replacement

horses in order to remain effective in hostile territory. They began to use

Arabian horses and mules more than the heavy Norman horses they had

brought with them. Food and water shortages killed many horses during

campaigns and sieges. It was a prolonged struggle to maintain a Northern

European war style in the Holy Land.

Horses in Peacetime

In the early Middle Ages, oxen were the main draft animals. In the wilder

places to the North, small shaggy ponies carried packs. Riding horses were

expensive, but wealthy men used them. Horses were seldom used to pull

carts or plows. The most normal peacetime use for horses seems to have

been as pack animals.

Horses could not be used in farming until two problems had been solved.

Their hooves were smaller and more easily damaged than an ox’s, and the ox

yoke could not easily be applied to the horse. The horse harness of the late

Roman Empire and early Middle Ages used a strap around the horse’s chest,

connected to a girth around its belly, to pull a load. But this chest strap cut

off the horse’s blood and air supply so that the horse could not use his full

strength.

The padded horse collar, fi rst invented in China and brought by stages

across Asia to the Mediterranean, solved the problem of a horse’s load-

pulling ability. It was rigid and padded; it fi t in front of the horse’s shoul-

ders, leaving the chest and windpipe free of pressure. The harness attached

the load to this collar so that the horse could lean his full weight against it.

Some medieval records suggest horses may have been able to pull 10 times as

much with the new harness. Horse collars were widely used around the time

of Charlemagne. The nailed horseshoe also appeared in Europe around the

ninth century. Horses with shoes could plow better in soft ground, and their

hooves did not split as easily.

The new technologies of horseshoes and the horse collar made horses

much better farm animals. The use of horses increased dramatically during

the reign of Charlemagne and his sons. Farmers began to raise oats as a

third crop, and they were used mostly to feed the horses. Horses became

more common on Northern European farms, but they were small, often

sickly animals. Peasant farm horses had problems with diseases like colic and

worms. They developed arthritis or got weak ankles.

In the Mediterranean regions, oxen remained the dominant plow ani-

mal, although some horses were used. Donkeys were more useful for pack

Horses

359

use and carts. Donkeys were used in Northern Europe, but they were much

less common. All these animals were used in all regions, but horses became

dominant only in the North.

Horses became more important on farms when towns grew and farmers

needed to carry food to market in carts. Horses had been used as pack ani-

mals before, but carts and wagons could carry much more. A packhorse

could not carry more than 400 pounds, but, with a cart, the same horse

could transport a ton of hay. Horse breeding and care became more im-

portant, and horse markets grew. Horses were bred for size, and, over the

last centuries of the Middle Ages, the average horse size grew by one or

two hands.

Large international horse markets were held in cities like Antwerp, Co-

logne, and Genoa. Large horse breeders sent agents into North Africa to

buy Arabian horses and combed Europe for the best stock. Horses from

the various regions across Europe were considered different breeds. The

most prized horses in Northern Europe came from Spain and were often

called Castilian horses. They were part North African Barb and perhaps part

Arabian. They were among the tallest horses. Arabian horses in the Middle

East and parts of Spain were small but very swift, had thin, elegant heads

and legs, and were valued for breeding. Hungarian and Danish horses were

smaller but were considered very strong, and Hungarian horses often had

slit nostrils to help them breathe better while running. Horses bred in Nor-

mandy were heavily muscled. Horses from southern Italy were light boned

and made good palfreys for riding but not destriers; northern Italian horses

were larger.

In the 12th century, London’s Smithfi eld Fair became known for

weekly horse sales that continued into the 19th century. Medieval horses

were generally divided into the uses they were trained for. A visitor to the

Smithfi eld Fair described seeing tall palfreys, warhorses, rounceys for gen-

eral riding, plow horses (also called affers), and pack horses (also called

sumpter horses). Some pack horses were mules, since donkeys were even

more plentiful than horses during the Middle Ages.

Palfreys were somewhat smaller than destriers but were nearly as expen-

sive and carefully bred. They were supposed to have quiet temperaments,

unlike the destriers. Palfreys were used for hunting, ceremonial parades,

and general travel among the aristocracy. Rounceys were grouped by the

gait they were trained to use. The gallopers were called coursers and were

ridden by men at arms and messengers. Some rounceys were trained to

trot and were used by gentlemen as their main riding horse. Amblers were

trained to walk with a simple rocking gait by moving their same-side legs

at the same time. Both left legs, then both right legs, moved in tandem.

This gait is not natural to horses. Amblers were the lady’s choice of a riding

horse; Chaucer’s Wife of Bath rode an ambler. Amblers were slow moving,