Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Hunting

380

Venery

Venery was the art of using a variety of dogs as a team and employing

strategy appropriate to the prey and the terrain. Hunting dogs went to the

hunt on leashes, controlled by trainers who could follow the huntsman’s

signals to leash or release their dogs at the proper time. Some dogs were

leashed in pairs and released as packs, while others worked alone. Breed-

ing the right kinds of dogs was its own full-time profession, as was training

each type of dog to its task. Some particular dogs became internationally

famous or were featured in poems about hunting, since they were the most

outstanding of their type. They were sought after for breeding.

Small hunting dogs that ran in packs were known by many different

names. They could have been different breeds or fairly similar. In medieval

hunting treatises, they are known as brachets, crachets, harriers, coursers,

or raches. They may have been similar to modern beagles, with large noses,

droopy ears, and big eyes. They were strong and fast; their main job was to

run fast and far. They were not expected to bring large prey down at the

end of the run. Harriers were particularly trained to chase hares, but they

also were used against other prey.

Greyhounds were large and thin. They were very fast, with narrow heads

and large jaws. They hunted by sight and could catch up with a deer and

bring it down with their jaws. Greyhounds came in different sizes and per-

haps slightly different breeds; good greyhounds were bred in Scotland.

They were supposed to have gentle dispositions outside of a hunt and were

among the dogs permitted into the lord’s hall.

Alaunts were like greyhounds but were stronger and could hold a fi ercer

prey. They had larger, blunter heads and very strong jaws. They could be

used for hunting deer but were the only kind of dog suitable for hunting

wild boar. The heaviest kind of alaunt was also used for bearbaiting. They

may have been similar to modern pitbulls or German shepherds, but, in the

Middle Ages, the best ones came from Spain. Alaunts had more violent tem-

peraments and were less intelligent than greyhounds. They had to be kept

leashed and muzzled.

Lymers were specialized tracking dogs, very much like modern blood-

hounds. They were kept leashed and were used to locate the scent of the

quarry. They were trained to run long distances following a specifi c trail,

to fi nd it again if it were momentarily lost, and not to bark. Very few ly-

mers were needed in a hunt, and they were trained to work alone. Lords

who kept large packs of hunting dogs had at least 20 other dogs for every

lymer.

Mastiffs were large, coarse dogs used as guard animals by shepherds and

as hunting dogs for particularly diffi cult prey. Mastiffs were shaggy and large,

and they were not purebreds. They had large teeth and often wore spiked

collars, since they guarded fl ocks against wolves.

Hunting

381

Spaniels and setters, and sometimes greyhounds, were trained to fi nd

and call attention to quarry, particularly kinds of birds such as quail or par-

tridges. They went out with falconers, and at times the greyhounds needed

to help a falcon kill a large bird such as a heron. Spaniels and setters only

found and roused birds. Other small dogs had their roles, but not necessarily

in an aristocratic hunt; terriers, for example, caught rats.

Royal kennels could be very large operations, with 30 full-time hunts-

men and pages caring for up to 100 dogs. The chief huntsman and his clerk

were at the top; at the bottom, some kennels allowed a few poor men to

sleep with the dogs for no wages. The kennels were warm, safe places, better

than the streets for the poorest.

Most huntsmen began as pages when they were young boys. They lived

with the dogs and learned all their names, and they cleaned the kennels and

changed the dogs’ straw bedding. Some kennels had straw-covered posts

for the dogs to urinate on, with channels in the fl oor to carry the urine

away. Kennels had enclosures where the dogs could walk and run, and the

pages took them out for walks on the grass. Pages brushed the dogs and

made leashes and collars. They looked for lost dogs, clipped toenails, and

soaked sore feet in vinegar. They were in charge of feeding the dogs their

ration of bread. Sick dogs might be fed tripe and blood from sheep, but

healthy dogs were not fed meat at home. Their trainers wanted them to as-

sociate meat with hunting and expect to fi nd it only in the forest.

As they got older, pages moved up to varlets, who helped handle the

dogs on a hunt. They learned how to track animals and interpret their

marks and droppings. They learned how to blow horns and how the hunt

was organized. Although they no longer lived in the kennels, some were

expected to keep a lymer in their rooms. As they moved up to the status of

full huntsmen as adults, they received higher wages, grander clothes, and

horses to ride. They still remained in close contact with the dogs, training

them and maintaining the dogs’ primary attachment. They had to over-

see and give orders to the varlets who held the dogs on leashes, and they

carried yard-long sticks to slap against their boots as signals. They carried

hunting horns and swords and knives to help fi nish off game. Lesser hunts-

men who remained on foot carried spears.

Huntsmen wore practical clothes without loose sleeves or long tunics to

catch on branches. In summer, they wore green, and in winter, gray. They

wore unusually high leather boots as protection against brambles. Not all

hunters followed these rules, but the professional staff in many illustrations

appears to work with rudimentary ideas of camoufl age. At other times, es-

pecially in the late Middle Ages, they wore the household livery, which may

have been gaudy and very far from camoufl age.

Hunting horns were most often made of the horns of cattle. Some were

made of brass and operated like modern bugles. Horns made of cattle horn

Hunting

382

were often bound in silver or gold, and the most expensive royal horns

were carved from ivory. All the hunters, professionals and aristocratic ama-

teurs, carried horns. They were all expected to use a communications code of

horn calls. Certain calls signaled types of deer or danger from wolves. Other

calls told the hunters when to assemble or what to do with their dogs, and

the dogs were trained to come to some calls. Some calls asked for water or

help. One such music was reserved for the death of the quarry, and the dogs

joined in with barking.

Dogs were expensive investments and merited more care than most medi-

eval animals. When a lord took his dogs a long distance to hunt in a certain

forest, he often arranged to carry them in baskets or cages. The dogs had

to be in their best shape when they arrived. Some dogs that were used for

hunting dangerous prey were given quilted dog armor to help guard against

claws and teeth. Dogs were frequently wounded while hunting bears and

boars. Their kennel staff used needles and thread to stitch gaping wounds

and sometimes used the ammonia of urine to sterilize a wound.

The day before a major deer hunt, or very early the same morning, one

or more lymers and their handlers scouted the forest for suitable quarry.

Some medieval illustrations show huntsmen studying the deers’ droppings

on a table; they were able to estimate age, size, sex, and general health.

They studied other signs, such as where the deer had rubbed its antlers on

a tree, and they measured the size and depth of its tracks. They wanted to

fi nd the best hart for the chase, and sometimes they were able to sight one

and count the points on its antlers. Deer tend to stay in one area of forest,

called a covert; before leaving, the huntsmen used the lymers again to tell

whether the harts they were studying had left the covert or not.

After the preliminary work was completed by the professionals, the aristo-

cratic amateur hunters arrived. As the hunt opened, huntsmen took groups

of dogs to relay points, depending on the terrain. They expected the fi rst

dogs to drive the hart past them so they could release fresh dogs to join the

tired ones. A huntsman and his lymer went to pick up the scent of the se-

lected hart. When the huntsman was sure the hart had noticed their pres-

ence and was running away, he tied the lymer up and blew his horn. The

running dogs entered the chase.

Huntsmen followed the progress of the dogs and communicated with

each other by signaling with horns. Each hunter and his set of dogs (bra-

chets, harriers, greyhounds, and alaunts) worked to follow the same hart,

not other deer, and make him run until he was tired. A tired stag turned to

fi ght with his antlers; this was known as the stag being “at bay.” Now the

hunters and dogs closed in, and, after a short time when the huntsmen and

dogs enjoyed the excitement, the hart was fi nished off with a sword or spear.

The hunters blew their horns, and sometimes they permitted the dogs to

bite the dead animal’s throat to keep their primitive hunting instincts fresh.

Hunting

383

The dogs received their share of the kill in a ceremony called the curée.

After the stag or boar was dead, the hunters leashed the hounds, which

waited while the deer was cut up. The dogs eagerly awaited the portions

left for them, which were entrails and blood-soaked bread. A hunter, or the

lord, held the animal’s head over the portion for the dogs, and the other

hunters blew their horns. The dogs were released to devour their portion.

The lymer often received the prize of being allowed to chew on the head

before it was taken back as a trophy.

The fallow buck was not hunted with the same scouting process using

lymers. Hunting a buck was less organized; the pack of running dogs was

permitted to fi nd the scent on its own. Roebucks were the smallest deer,

the least useful for feast tables. They had great running stamina, so hunt-

ers used relays of dogs to chase them. Some hunters did not consider them

worth eating and used them only to train dogs.

Another medieval hunting method was to drive the quarry toward a hid-

den group of archers. This method may have been the oldest, and it seems

to have been the Anglo-Saxon method; it was also used for does and hinds

during their hunting seasons. Ladies who participated in hunting were re-

stricted to this method, which was safer and usually took place in an en-

closed park. The royal party with its ladies went to an appointed place and

hid with their bows. Hunters with a few dogs drove the deer toward them.

Sometimes long lines of people helped corral the deer into the preferred

path toward the archers; they were known as the “stable.” Deer parks could

be designed with natural features to create a stable, or hunters could put up

barriers or nets. When the group of hinds ran past the hidden archers, the

ladies could try their shooting skill. One arrow was not always enough to

kill a deer, but the hunters were nearby to fi nish them off with knives.

Falconry

Falcons and hawks are natural predators of birds and small mammals,

but, although fi erce, they can be tamed. Both are raptors—birds that kill

live prey—and diurnal hunters, not nocturnal like owls. Hawks follow their

prey at a low altitude, while falcons swoop down from above. Falcons have

a wider wingspan than hawks. Falcons were more often used in medieval

hunting, so the sport is generally known as falconry. Falconry was especially

popular with ladies, since they were strong enough to ride a horse and hold

a small bird. It was the most popular kind of hunting in medieval Spain and

Italy, perhaps because game was smaller in these warmer, more settled re-

gions where deer had become scarce.

Female falcons and hawks were always larger and stronger, and better

hunters, than males. The largest of the raptors were the Greenland gyrfal-

cons, which were strong enough to catch water birds like cranes and herons,

Hunting

384

as well as small animals such as hares. They were heavy and hard to train, and

they were relatively scarce. Peregrine falcons were more common; they were

native to Africa and Europe and were the most common Spanish falcon. The

merlin was a small peregrine hawk used to catch birds up to the size of quail.

Some minor falcons are not well-known today. The hobby was a very small

falcon, too small to use for useful prey but a good starting bird for beginning

falconers. The saker was an Arabian falcon used in Spain, while the lanner was

a bird whose range used to be all over Europe but is now restricted to the

Mediterranean. Two raptors were true hawks, the goshawk and the sparrow

hawk. The goshawk was larger and could catch hares as well as quail and even

herons. The female sparrow hawk was a convenient size for many ladies to

carry, and it could take down small birds like larks or even partridges.

Most birds were captured in the wild. Young adults were favored, since

birds in the nest were easy to tame but did not know how to hunt. Falcons

were gentler and easier to train than hawks, and some lords kept a favorite

falcon in their chambers. All training followed basic principles that began

with blinding the bird, either by covering its eyes with a leather hood or

stitching its eyelids closed. The bird became dependent on human contact

for food and grew tame. When its sight was restored, it was trained to fl y

away and return to its home and to sit on a keeper’s leather-gloved fi st. It

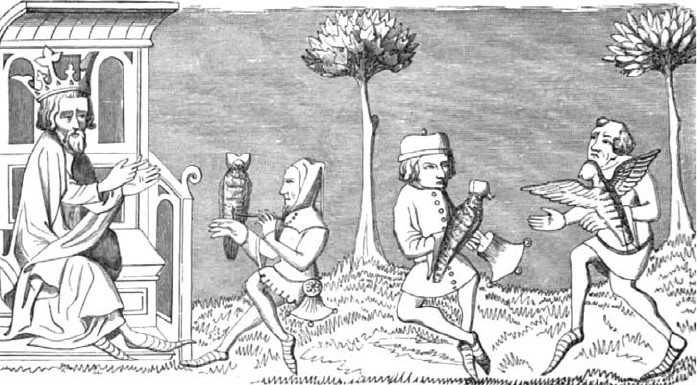

Falconry was the noblest, most expensive sport, so it was often pictured in books and

on walls. Trainers learned to know everything about their falcons’ health, habits, and

personalities. They trained the birds to believe that the way to be fed meat was to

catch some prey and bring it back whole, in order to get a bit of raw chicken from the

trainer’s hand. The bird’s view of the world had to be carefully shaped by the trainer,

who kept its eyes covered with a tiny leather hood much of the time. (Paul Lacroix,

Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au Moyen Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance, 1878)

Hunting

385

wore jesses—leather collars around its ankles—each with a ring to which a

leash could be clipped. In many regions, birds wore tiny bells to help the

falconer fi nd them after they had seized prey. They were also trained to seize

a lure that was shaped somewhat like a bird, with meat attached, and whirled

through the air on a rope. This allowed the falconer to recapture a bird. The

birds also had to be trained to go after prey they did not naturally favor.

Large birds, such as herons and cranes, required special training to give the

falcon or hawk confi dence. Most cruelly, some royal trainers used crippled

live cranes. In some training, raptors were permitted at fi rst to eat the prey,

but they were otherwise strictly trained to think that bits of meat always

came from the hand of a human.

Falcons and hawks lived in mews, if they did not live in the trainer’s or

lord’s chamber. The mews were kept clean, with sand sprinkled on the fl oor,

so the keepers could tell if the birds were coughing up or excreting mate-

rials that indicated illness. The birds sat on perches both in the mews and

in the cages (at that time spelled cadges ) that transported them. The cages

hung over a man’s shoulders on straps and were fi lled with padded perches.

Because falcons were such expensive creatures, their veterinary care was the

greatest of all medieval animals, even more than dogs and horses. All fal-

cons and hawks molted once a year, losing all their feathers and growing

them back. During this time, their keepers watched their health anxiously,

and keepers employed favorite methods for helping the feathers regrow as

quickly as possible.

In the hunt, both dogs and human assistants were needed. Spaniels and

setters helped locate the birds or hares and could chase them into the air

or into the open. Some falconers paid small children to beat the bushes so

ground birds or hares would dart out. When the birds killed game across

or in water, either the dogs or the beaters were expected to swim out and

retrieve it. A well-trained falcon brought its catch back to its master’s feet.

The bird was rewarded with meat tidbits, and the hunters cut up the game

in an informal curée ritual so the raptor could be rewarded with pieces of its

quarry.

Falconry was the main source of game birds such as partridge and quail. In

some places, by the 15th century, commoners were catching and training fal-

cons and hawks. Falconers also went to war with kings to provide entertain-

ment and to catch game for dinner between battles. Expert falconers were in

demand all over Europe and often found employment in foreign courts.

See also: Animals, Forests, Robin Hood, Weapons.

Further Reading

Allsen, Thomas T. The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History. Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Hygiene

386

Almond, Richard. Medieval Hunting. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2003.

Blackmore, Howard L. Hunting Weapons from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth

Century. New York: Dover Publications, 2000.

Cummins, John. The Art of Medieval Hunting: The Hound and the Hawk. Edison,

NJ: Castle Books, 1998.

Griffi n, Emma. Blood Sport: Hunting in Britain Since 1066. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press, 2009.

Norwich, Edward of. The Master of Game. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2005.

Oggins, Robin S. The Kings and Their Hawks: Falconry in Medieval England. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

Reeves, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

Hygiene

It is widely believed that people in the Middle Ages were very dirty. This

is at least half a myth. Many people were dirty because they had occupa-

tions that left them soiled, and whole-body bathing was expensive. But a

great deal of daily washing was routine for all but the beggar class, and, in

many of the medieval centuries, there were whole-body baths of some kind

going on in many regions. Hygiene improved through the Middle Ages

but dropped again with more crowded conditions and industrial waste. The

plague forced a crisis of public hygiene because many bodies had to be bur-

ied quickly, and it was diffi cult to stay clean.

Roman society had prized cleanliness, and most Roman cities had pub-

lic baths. Italian cities inherited this infrastructure, and some cities were

able to maintain it. Even in the disorganized period after the barbarian in-

vasions, many Italian cities and towns kept up public baths and even tried

to build new ones. Some bishops sponsored public baths near their cathe-

drals. Public baths, even including soap, became part of alms for the poor.

By the 10th century, public baths were no longer as popular in Italy. Those

who could afford them built bathing rooms in their houses.

In Benedictine monasteries, the norm was that the monks washed their

faces and hands several times a day in a trough of cold water and bathed

their whole bodies in warm water up to four times a year. They washed their

feet once a week and had their heads and faces shaved every two or three

weeks. Monasteries and convents sometimes placed washstands in each cell.

This washstand had a basin to catch wastewater, a water reservoir of some

kind that could hang above the stand, a shelf for soap, and a rod for a towel.

A public lavatory with a permanent washbasin sometimes was equipped with

a roller towel.

Most people washed their faces and hands daily. The wealthy washed their

hands before and after meals, since they ate with their fi ngers. At a feast,

Hygiene

387

servants known as ewers carried around pitchers of water and bowls to catch

the wastewater. They poured water over guests’ hands with specially shaped

aquamaniles or simply with pitchers that also came to be called ewers.

By the end of the Middle Ages, some private homes in cities had wash-

stands modeled after the lavatories in monasteries. On the wall was a hang-

ing reservoir with a tap and, below it, some kind of basin to catch the water.

The most advanced were built into the wall and had a drain hole to carry

the wastewater down a pipe.

Physicians believed that sickness was caused by an imbalance of heat,

cold, dryness, and moisture in the body and that opening the body’s pores

to outside infl uences could cause illness. Their opinion was that getting the

body wet all over would open it to chills or fevers and was not safe. Wash-

ing anything but visible dirt from the face or hands was openly discouraged.

However, being dirty was associated with being poor. People who could af-

ford to bathe their whole bodies did so once a week.

These baths were in wooden tubs, with heated water, with a linen cloth

laid on the bottom of the tub to guard against splinters. Wooden tubs were

built like barrels, but coopers made them especially for bathing. They came

in various sizes, from small tubs for feet or babies to large tubs that fi t sev-

eral people. They usually had two handles with holes so they could be lifted

by hooks or on a pole and moved to another place. In large tubs, these

handles were big enough to act as backrests for the bathers. The bathtub

could be used outside in summer and by a fi re in winter.

Aristocratic baths were a luxurious experience, even by modern stan-

dards. By the 14th century, kings of England had permanent bathrooms

with piped-in hot water and tiled fl oors. A 15th-century manual for train-

ing servants stipulated that the bathtub needed sponges to sit on and to

use for washing. Sheets had to be hung around it for privacy and warmth.

For those who could afford these luxuries, water for washing and rinsing

was scented with roses. By the late Middle Ages, aristocrats expected to fi nd

rose petals in all washing water. A full-scale bath was required before a cer-

emonial event such as a wedding.

For well-to-do royals or commoners who owned a wooden bathtub, the

work of heating the water for the bath meant that more than one family

member would benefi t from it. Bathing was often a group activity, and nu-

dity was not as shocking since there was little privacy for dressing and sleep-

ing. Some medieval illustrations of public baths show several people in a

large tub, with a shelf containing snacks along one side of the tub.

Some large cities had public baths as well as public latrines. The idea

may have come from the public baths available in the Muslim world; some

bathhouses used the symbol of a Turk’s head to suggest their service. In

medieval English, they were called stews. Some bathhouse owners built near

the operations of bakers to make use of the heat already being generated.

A bath scene illustrates a 15th-century tale about King Arthur’s knights. The artist

depicts a bathtub accurately: the tub was a large, wide half-barrel that needed a linen

lining to guard against splinters. Perhaps the fantasy stories of the Round Table

knights have prompted the artist to show a knight in full armor attending on the

bath. In reality, steel armor was kept dry, oiled, and as far from water as possible. But

although no aristocratic medieval bather would ask a knight to attend the bath

wearing armor, neither would he dream of bathing alone. A proper bath required a

team of servants to fetch, carry, heat, pour, wash, dry, and drain. (Giraudon/Art

Resource, NY)

Hygiene

389

The owners charged for steam or tub baths. In some, barbers offered

shaving, haircuts, and services for bleeding and cupping (a milder form

of bloodletting). People socialized in bathhouses and did not always keep

them segregated by sex. Owners were supposed to keep out lepers who

might pass on infectious disease and to prevent bathhouses from being used

as centers for prostitution. Gradually, the price of fi rewood made bath op-

erations too expensive. City governments viewed public baths as too com-

monly linked to prostitution and immorality and were afraid of contagion,

especially after the Black Death. By the end of the Middle Ages, public

baths were out of business on their own or closed by ordinance.

A much less common but possible alternative was the steam bath. The

idea of the steam bath, or sauna, may have been introduced from the Middle

East, where it was a bathing option that did not use much water. Enclosed in

a small room, tent, or garment, the bather endured a small amount of water

creating steam over hot coals. Herbs always went into the water to perfume

the steam. After a steam bath, the bather needed only a quick rinse.

Medieval people had soap but may have used it more often for washing

clothes than for washing skin. It was expensive because it used fat, which

was precious for cooking. Soapwort, a washing herb, was the poorer per-

son’s alternative. Soap varied by region. In Northern Europe, animal fat

was used. The wood ash used to make soap was high in potassium, and it

made only soft soap that was kept in a small tub. In Mediterranean regions,

soap was made with olive oil. Barilla ash was high in sodium and made a

hard, pure bar of soap. Castile soap, imported from Spain, could be pur-

chased from merchants. It was very expensive, and only the wealthiest aris-

tocrats could afford it, perhaps scented with lavender.

Hair could be washed separately. Aristocrats probably washed their hair

once a week, common people less often. The procedure for washing hair was

to strip to the waist, with a pitcher of water and a wide, shallow basin on a

fl oor mat. The hair washer knelt on the fl oor, bent over the basin, and used

soap, the pitcher, and the basin to complete the task.

Shaving was not accessible to most common people, since it required

water, soap, and a sharp blade. Only the wealthiest would have been able to

shave every day. In towns with barbers, most men would go once a week.

Barbers used straight blades that required real trained skill to manage with-

out danger to the client. In monasteries, shaving was a routine matter, since

monks were required to shave the tops of their heads, as well as their faces.

They shaved once every two or three weeks. At fi rst, the monks were sup-

posed to learn to shave each other, but many monasteries had to hire a pro-

fessional barber. Shaving was taking too long, and too many monks were

getting cut.

Personal care beyond face washing varied greatly, but there were some pos-

sibilities. We are dependent on written records and pictures, and, although