Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Horses

360

and they were bred and chosen for their easy-going natures. People who

were inexperienced riders always hired amblers for journeys. Jennets were

smaller horses for aristocratic ladies. They were probably more Arabian in

breeding, since they came out of Spain. In Spain, jennets were used as war-

horses.

In towns, few people owned horses. Towns were small, and most people

could do their business on foot. Horses were for long journeys and had to

be rented. On these journeys, horses ate a special type of bread baked for

them, made of beans and peas, along with the ordinary hay. Businessmen

who rented horses for a living were called, in medieval English, hackney-

men. The daily hire for a horse might equal the day wages of a skilled laborer,

so hackneymen were certainly able to make a good living. On routes with

high traffi c, such as London to Dover, hackney horses were often branded

to discourage theft. Chaucer’s Tabard Inn, where his company of pilgrims

met to start for Canterbury, was one place to rent horses. These horses

made the journey to and from Canterbury repeatedly.

Medieval people raced horses, although, in most times and places, the

game was restricted to those who could afford horses: the aristocracy. In

Italy, however, the cities organized horse races to celebrate the holidays of

their patron saints. By the 14th century, the races, called palios after the

traditional prize of a costly palio robe, were well organized and traditional.

Boys, sometimes dressed in the livery of the guild that employed them, were

the jockeys, and the races were often run in the city square, rather than in a

fi eld outside the city.

By the 15th century, horses were bred

and trained for riding nearly as often as

for harness. In this drawing, the horse

appears to have black iron shoes, in

addition to a full harness holding the

saddle securely. Proportions in medieval

illustrations are not very accurate; the

human rider (here, Chaucer’s Wife of

Bath) may not have been quite this

large in comparison to her mount.

However, medieval horses were

generally smaller than modern horses. A

lady’s riding horse may not have been

much bigger than a modern Welsh

pony. (John Saunders, Canterbury

Tales: Annotated and Accented with

Illustrations, 1894)

Horses

361

The Muslim warriors of Persia invented the game of polo during the

Middle Ages. Polo was their war training game, as jousting at tournaments

was battle training for Northern European knights. Polo required the

horses and riders to be trained to work together and to make quick turns

and sudden stops.

Horse Equipment

One of the key inventions of the Carolingian era was the iron horseshoe.

This piece of equipment permitted horses to work harder and run farther

without wear on their hooves. In the damp climates of England and France,

horses’ hooves were softer and wore out more quickly than in the dry cli-

mates of Spain and North Africa. Although nailed-on horseshoes caused

their own problems, their benefi ts outweighed the disadvantages. Medie-

val horses were almost universally shod. Horseshoe nails were hand ham-

mered and square. The holes in a medieval horseshoe were also square. A

typical shoe had eight holes.

Farriers were also called marshals in medieval English, and the house-

hold division overseen by the marshal was a marshalsea. The marshal of a

noble household oversaw the care of all the horses, including the hire or

maintenance of wagons and carts. He supervised the grooms and stable

boys. Although marshals began as horseshoe specialists, they also became

the horse veterinarians of the time.

For shoeing, horses were put into a wooden frame called a travis, or tra-

vail in medieval French. The frame was only somewhat larger than a horse’s

body, so it hampered the horse from moving. His head stuck out of the

frame so the owner or another handler could hold it; at the back, there was

a bar to rest or even tie the foot being shod. The travis was normally open

but could have a roof over it. It was used not only for shoeing, but also for

other veterinary work.

Medieval bridles were very similar to modern ones. A leather harness

went over the horse’s ears and down the face to the jaw. Here it attached to

a metal bit that went over the horse’s tongue. The reins held by the rider

seem to have been a pair of single straps, rather than a continuous U -shaped

strap. Since horses were luxury goods themselves, their equipment was of-

ten decorated. A horse’s bridle often had decorative bosses attaching the

straps. The straps themselves often had diamonds, rosettes, or other heral-

dic emblems attached to the leather.

By the late Middle Ages, bits and stirrups were made by specialized black-

smiths called loriners (or lorimers). The bits were made of iron, bronze,

or copper. There are two basic modern types of bit, and both were used in

the Middle Ages. The snaffl e bit is a bar, solid or hinged, that attaches to

the bridle with rings. The curb bit attaches the mouthpiece bar to a set of

Horses

362

levers, and the bridle connects to the bottom of the lever that hangs below

the horse’s jaw. When the rider pulls on a snaffl e bit, the horse’s mouth feels

only the direct pull, but a curb bit provides the rider with greater pressure

from the levers. Curb bits were more popular on medieval bridles after the

13th century.

The medieval saddle was similar to a modern saddle. It was made of a

wooden frame that was stuffed and covered with leather. Arab saddles were

lightweight and had short stirrup straps, but the European saddle developed

into a heavier seat. The knight’s saddle was particularly specialized. It had

a tall pommel in front, which widened into a protective piece called a burr-

plate. The saddle provided an extra wall for the rider’s crotch and upper

legs. The saddle had a high cantle at the back, which boxed in the knight’s

armor and helped keep him steadily seated. The saddle’s framework, the

saddletree, was made of beechwood. Two pieces of wood rested on each

side of the horse’s backbone and joined in the middle, held by the burr-

plate in front and the cantle in back. Leather and sheepskin padding fi lled

out the seat, which rested several inches above the horse’s back.

The knight’s saddle had an elaborate harness. While a modern saddle is

held only by the girth strap, the medieval saddle also had a breast strap and

a strap that ran around the horse’s rump called the crupper. These straps

were necessary to help the knight withstand the shock of battle lest his sad-

dle slide out of position. However, they also became opportunities for dis-

play. Many illustrations show riders with pendants hanging off these saddle

harness straps. Popular pendant shapes were crosses, shields with coats of

arms, and geometric shapes or fl owers.

In addition to the breast strap and crupper, the saddle had leather straps

to hold the stirrups. The stirrup straps were a key part of the saddle; knights

stood in them and leaned their whole weight against them in jousting. Be-

cause knights needed to stand, the stirrup straps were longer than modern

ones; knights did not ride with bent knees. Stirrups made by loriners came

in various shapes. One jousting style tapered toward the toe so the knight’s

foot could not slip forward. If he fell, he needed to fall cleanly and not have

a foot hung up in a stirrup.

An important piece of horse equipment was a pair of spurs for the rider.

Spurs became a symbol of knighthood, especially if they were golden. Spur

making was its own craft, represented by the guild of the spurriers. Ordi-

nary spurs were iron or brass. Spurs came in two basic shapes. The prick spur

was the earliest kind, but, during the 13th century, the rowel spur came into

use. The rowel spur had a wheel with many spikes on it, but, in many cases,

the spikes were more rounded than sharp. Long spikes were used mainly

by knights whose horses wore quilted padding. Like other pieces of equip-

ment, spurs could be highly decorated—perhaps more so since they were

worn by the rider, not by the horse.

Hospitals

363

Warhorses began wearing their own armor during the 12th century. Fab-

ric armor was called caparison; it was quilted and could only protect a horse

from accidental, glancing blows and scratches. Chain mail was the next

step, placed over the caparison. By the end of the Middle Ages, the largest

horses of the wealthiest knights were wearing steel armor on chest, head,

neck, and even body.

Excavations have uncovered currycombs that are very similar to modern

ones. The combs have a broad blade with saw teeth and a handle attached.

The horse’s hair is cleaned by combing the teeth gently across the horse’s

body, removing loose hair and dirt.

See also: Agriculture, Armor, Knights, Tournaments.

Further Reading

Clark, John, ed. The Medieval Horse and Its Equipment. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell

Press, 2004.

Clutton-Brock, Juliet. Horse Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

1992.

Davis, R.H.C. The Medieval Warhorse. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

DiMarco, Louis A. War Horse: A History of the Military Horse and Rider. Yardley,

PA: Westholme Publishing, 2008.

Hyland, Ann. The Medieval Warhorse from Byzantium to the Crusades. London:

Grange Books, 1994.

Kelekna, Pita. The Horse in Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2009.

Langdon, John. Horses, Oxen, and Technological Innovation. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press, 1986.

Oakeshott, Ewart. A Knight and His Horse. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions,

1998.

Resl, Brigitte, ed. A Cultural History of Animals in the Medieval Age. New York:

Berg, 2007.

Hospitals

In medieval Europe, the fi rst offi cial hospital care came with the establish-

ment of Benedictine monasteries. Hospitals cared for the old, perhaps the

largest category of sick people. They also cared for those born crippled, or

who had become crippled or paralyzed in accidents, and for the blind or re-

tarded. People with serious epilepsy, known as “the falling sickness,” found

a home in some hospitals. Contagious illnesses were not among the con-

cerns of most hospitals, since they were dangerous for the staff. Leprosy

was handled separately through dedicated leper hospitals and colonies.

The Roman army had included hospital care for their sick and wounded

when planning forts. These hospitals were the fi rst in Northern Europe,

Hospitals

364

but their closure with the Roman army’s withdrawal meant that the hospi-

tal had to be developed again separately. There were Roman-style hospitals

in Constantinople as early as the sixth century. In a Byzantine hospital, pa-

tients could recover from an infection or have a simple surgical operation.

The Byzantine model became known in Europe after the Crusades, and it

helped reorganize the kinds of hospital care already available.

General Hospitals

The Rule of Saint Benedict required monasteries to set aside a few

rooms for the care of the sick and an offi cer to look after them. The sick

were to have a good diet and regular baths. The poor, too, were to receive

help if they asked, and their sick could petition for care. By the late Middle

Ages, a monastic infi rmary offered the best possible care for the sick, who

not only enjoyed warm rooms and meat every day, but also might listen to

harp music to cheer their spirits.

In Latin, a medical hospital was called domus dei, a house of God. The

term hospital originally meant a place to care for travelers, like the modern

word hostel . The Order of the Hospital was an order of knights sworn

to protect travelers in the Holy Land. The word hospitium in Latin became

hospitale ; for a time in medieval English, the word for a house for the sick

was simply spital .

Constantinople had hospitals supported by the state, and early medieval

Italy also developed simple hospitals for the sick. There are few records of

hospitals in Northern Europe until the 11th century, although their subse-

quent rapid development in England suggests there were more hospitals in

France and Germany.

Lanfranc, the fi rst Norman archbishop of Canterbury after the Norman

conquest of England, set up a building outside the town gates for the care

of the sick. It had a men’s wing and a women’s wing, with funding for a care

staff. In a separate location, he established a leper colony. Lepers and other

invalids were not cared for together, since leprosy was known to be conta-

gious, while other diseases were not. In the fi rst century of Norman rule,

at least 60 more hospitals were established. Some were leper colonies, but

many were not. Most grew up near highways where many travelers passed,

and the earliest ones were built, like Lanfranc’s, outside the town walls on

an empty lot.

During the Middle Ages, religious orders were founded specifi cally to

care for the sick and poor. The Order of the Hospital spread from the Holy

Land into the rest of Europe, eventually reaching England in 1128. They

operated hospitals for the sick in some parts of Europe, supported by in-

come from estates donated by the pious. The Hospitallers based their

model of operation on the Byzantine model they came into contact with in

Hospitals

365

Jerusalem. Their primary hospital, in Jerusalem, may have had as many as

1,000 beds for patients.

The Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem was a religious order dedicated

to the care of lepers. Its houses spread across Europe. Other religious or-

ders for the care of the sick included the relatively small Order of Saint

Thomas the Martyr of Acon, an English order that failed in its intention to

found hospitals around Europe but did administer one large London hospi-

tal. Saint Mary of Bethlehem was another order founded in the Holy Land;

it founded fi rst a priory and then a hospital in the 14th century. Its ordi-

nances permitted it to accept the mentally ill, and later that became its main

mission; Saint Mary of Bethlehem was shortened to “Bedlam,” the name of

London’s mental hospital. A Provençal monk founded the French Trinitar-

ian Order, which administered hospitals and almshouses across Europe.

Most city hospitals were under the control of the local bishop, and the

church normally provided funding and staffi ng. Individuals were encour-

aged to give charitably to hospitals, and some of the wealthiest, usually roy-

alty, founded hospitals. But most hospitals are hard to distinguish, in

records, from the religious houses they were part of; they were also hard to

distinguish from almshouses that cared for the poor, rather than the sick.

The Hôtel-Dieu in Paris was an early medieval inn and hospital for the poor

and pilgrims; it fulfi lled both functions. Paris also had a hospital for the

blind, as well as leper hospitals ( leprosaria ).

Charitable societies in late medieval Italy set up hospitals in many cities.

Milan had 10 hospitals, and Florence had at least 30. The charitable societ-

ies and commune governments kept surgeons on their payrolls, and guilds

helped inspect the hospitals. These hospitals cared for all kinds of poor and

sick, including orphans and the aged. The development of medical schools

in Italian cities such as Padua, Salerno, and Bologna raised the level of med-

ical care. French and English hospitals lagged behind and continued to give

mostly food and rest.

Hospitals had a prime function of looking after the spiritual welfare of

their patients, not their medical care. Priests and chapels came before medi-

cine in priorities of time and money. Since the staff members were mostly

monks and nuns, they had already made vows to keep the hours of prayer

and say Mass every day. The inmates of hospitals, where able, participated

in this rigorous life of prayer. The next development was for hospitals to de-

velop small choir schools so they could help the children of the poor while

providing a choir for the Mass.

Hospitals gave medical care, but some restricted the type of care they

would give. Many excluded lepers, but some also excluded pregnant women,

epileptics, and the insane. Each hospital’s ordinances declared what its con-

ditions were. Some hospitals were closer to almshouses or nursing homes,

while others took any sick people and did not limit the time of stay. Guilds

Hospitals

366

established hospitals and almshouses for their own members or for members

of similar trades. Depending on the type of patients a hospital took in, there

may have been work programs. Poor or blind women could still spin, and,

depending on their disabilities, some others could do chores. Long-term

hospital inmates often wore uniforms, robes of a certain color, or the same

insignia badge as the staff.

Some hospital ordinances required the hospital to take in pregnant

women; these women were probably homeless or very poor, and many

were servants or prostitutes. In some communities, hospital services had

to be established just for this need. The legendary lord mayor of London,

Richard Whittington, established a small hospital for unwed mothers in the

early 15th century. Some hospitals took in foundlings (abandoned babies )

and orphans and would care for them to the age of seven.

Hospitals needed funding sources and, like modern charities, were con-

stantly seeking money to maintain and expand services. Some hospitals

were granted toll rights for ports or ferries and reaped a sales tax on things

like casks of wine. They actively solicited support from tradesmen and

The Hôtel-Dieu in Paris was one of the fi rst real hospitals. This engraving shows a

typical ward in the 16th century; little had changed since medieval times. Patients

shared beds, since beds were scarce and contagion not well understood. The sisters, in

sober uniforms, bring the sick basic care such as food and water. They have the added

task of preparing the dead for paupers’ burials. The large hall appears to be a medieval

hall converted to a sick ward; this was often how hospitals began. (Paul Lacroix,

Science and Literature in the Middle Ages, 1878)

Hospitals

367

landowners for charitable gifts of money and food; some guilds gave ale or

meat. Other sources of support were people who paid the hospital an an-

nual fee in order to be received into a room in old age. Like other branches

of the church, hospitals could sell indulgences that procured forgiveness for

loved ones in purgatory. Wealthy dying people wrote hospitals into their

wills as expressions of repentance and in hope of excuse from purgatory.

Hospitals were exempted from taxation by the church or king.

When people donated buildings to establish hospitals, the buildings had

to be adapted. One common adaptation was to construct individual rooms

down the length of a hall, leaving the center fi re pit and a common area

open. The pillars that supported the roof provided a natural spacing for

the divisions. At the end, where the lord’s dais had been, another partition

could form a small chapel.

In the days before medical technology, a medieval hospital’s greatest in-

vestment in equipment was in purchasing beds for the patients. Beds typi-

cally had straw mattresses held by a rope foundation on a wooden platform

and were large enough to fi t at least two patients. The beds were not as

fi ne as four-poster curtained beds in a wealthy home, but they were much

better than what the poor were used to. When wealthy people were dying,

sometimes they willed their bed to the nearest hospital as a charitable do-

nation.

Medieval English hospitals were usually fairly small, and they were al-

ways named for patron saints whose help was sought for the sick. They

were required to have a chapel and their own cemetery for the burial of sick

paupers. The largest hospitals could have over 100 beds and about 25 staff

members—a mix of monks, nuns, and servants. All through the Middle

Ages, hospitals employed more women than men. Most were not nuns, but

were lay sisters or hired servants. By the end of the period, many hospitals

had a special badge for staff to wear. Most often, it was a cross. The admin-

istrator, the master, wore a different colored robe or badge.

Saint Leonard’s Hospital in York was the largest medieval English hos-

pital; it was a true hospital for the sick. It had around 200 beds, and its

nuns and monks included those with medical training gained by practical

learning, though not university medical training. It kept 18 orphans, at

least until the hospital was overwhelmed by the Black Death plague. Local

apothecaries supplied the hospital with spices for common medicines, and

most likely they kept an herb garden to grow medicinal plants. However,

the sick still received mostly ordinary care such as food, washing, and a

heated room to sleep in. The sickest patients were fed in their beds, and the

blind or crippled were helped to move about. This may have been enough

to help some of the sick recover. For others, it provided some comfort be-

fore death. In a most unusual touch, Saint Leonard’s hung lanterns in the

wards at night. Only hospitals kept lights burning in the dark.

Hospitals

368

European hospitals came under great fi nancial stress when the Black

Death struck. A lot of wealth was lost when so many people died and busi-

nesses collapsed, and some hospitals saw most of their staff wiped out by

plague. In many cases, small hospitals continued to exist in name, owning

the assets they had before, but there were few or no patients. The surviv-

ing staff often used the hospital’s fi nancial support to keep its schedule of

prayers and Masses. Sometimes, several small hospitals combined, and, in

cases where the Crown had been supporting a hospital, it deeded the hos-

pital to the town. The town could decide how to manage it or whether to

close it. Hospitals in Italian towns began to specialize and became orphan-

ages or medical hospitals, rather than both. Orphans and foundlings were a

pressing concern with so many mass deaths.

Hospitals became targets for mismanagement and embezzling even be-

fore the crisis of the plague. In 1311, the Pope decreed that all hospitals

must be audited to make sure the foundation money was not being siphoned

off for use by a few. In church and town investigations, some hospitals were

found to have roofs collapsing and either inadequate care or no care at all for

their inmates. Milan lost some of its hospitals, and Florence’s largest hospital

was found to be holding fraudulent government bonds. A wave of hospital

reform came at the end of the 14th century, with the earliest signs of the

coming Reformation. New foundations were established, for the most part

smaller and more limited than the earlier ones. More almshouses (old-age

homes for the poor) were founded than hospitals for the sick.

Care of Lepers

Lepers lived in separate colonies, apart from the populace. Although the

word leprosy dates into antiquity, another term for a leper colony or house in

medieval English was Lazar-cote or Lazar-house . These were not hospitals,

although they provided hospice care to the dying. There was no treatment

for leprosy, but some lepers lived reasonably independent lives for many

years, so they were more like isolated villages. These colonies were self-

governing, and some lepers had children. Provisions were not as careful as

at hospitals, since lepers were permitted to beg or garden. Leper colonies,

or isolated houses for individual lepers, had to have their own water supply

and utensils. Lepers had to wear boots and gloves if they went out.

Most cities also established real hospitals for lepers. Only the sickest were

admitted, and it was a privilege, not apparently a public-health measure.

A leper hospital was similar to a monastery in both dress and daily rou-

tine. The lepers were required to spend long hours at prayer, repeating the

Lord’s Prayer many times a day. When one of their number died, they made

additional prayers for the departed’s soul. Lepers who were committed to

Hospitals

369

the hospital and not permitted to leave could be punished for fi ghting by

withholding food.

Lepers often went through a formal legal death before admission to the

hospital or colony. Under the shelter of a black cloth, the leper gave his last

confession and heard Mass, and the priest cast a handful of dirt on him, as

if burying him. The leper left with the black cloth as a shroud. In the hospi-

tal, he made out a last will, leaving a substantial portion of his property to

the hospital.

The provisions at leper colonies and hospitals were generally poor. In

both colonies and hospitals, lepers were not only permitted but were ex-

pected to beg for alms. It was their way of supporting the hospital. Some

leper hospitals had gardens, and the patients had to work to help feed the

community.

Leper hospitals were like monasteries to the extent that if a man and wife

both had leprosy and were admitted, they would live apart in the men’s and

women’s houses, supervised by monks and nuns. A man could only enter a

leper hospital if his wife entered a convent or was too old to remarry. At fi rst,

the church had permitted leprosy as grounds for divorce, but, by the 12th

century, the Pope enjoined spouses of lepers to care for them.

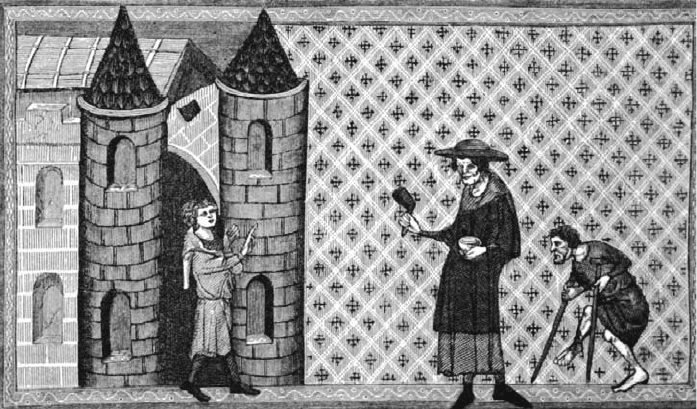

A wall painting shows a charitable leper hospital with begging lepers in front. They

wear paupers’ dress, a somber black uniform. One has lost a limb to leprosy and must

use crutches; the other carries a noisemaker to alert healthy citizens to their presence.

Leprosy was a humiliating disease; lepers had to beg in order to help with hospital

expenses, but they had to wear gloves and stay far away from healthy people. (Paul

Lacroix, Science and Literature in the Middle Ages, 1878)