Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Jewelry

400

times, as Scandinavian ships carried amber out of the Baltic Sea and traded

it in France and England. Garnet is a mineral that came in a variety of col-

ors. Its most common medieval form was dark red, as found in Bohemia,

and some other forms came from Asia Minor and Russia. Jet is not a true

mineral but is closer to petrifi ed wood. It is pure black and can be polished

to a glossy sheen. It occurred naturally in parts of England. Beryl is a trans-

parent mineral that is colorless but often occurs with color tints. It had

been known since classical times and occurred in many parts of Europe.

A few other minerals native to Europe made good jewelry. Rock crys-

tal, a form of quartz, sparkled and could be used as itself or in imitation of

other gems. It was not a real gemstone, but it was pretty and popular for

many articles. It could be found easily in Germany and France. Pearls are

not native to the Mediterranean Sea, and most pearls came to Europe from

the Indian Ocean, but some river pearls came from Scotland (and later

from Bohemia). A freshwater mussel that lived in Scottish rivers produced

a small pearl that could be pierced and sewn onto clothing or mounted as

a small gem. Toadstone was a fossilized fi sh tooth, but medieval people be-

lieved it came out of a toad’s head. It was brown, and it polished well and

was thought to bring good luck. Finally, Roman cameos were recycled into

medieval jewelry. They had been left in Roman ruins, and people often

Square-headed brooches were almost universal

in early medieval Europe. The Franks and the

Anglo-Saxons probably borrowed the form from

Roman models. The square at the top held a

hinged pin, while the cross shape at the bottom

concealed the pin’s clasp. The bridge between

these parts held the gathered folds of a cloak or

tunic. Brooches like these are found in

many pagan graves. (Museum of London/

StockphotoPro)

Jewelry

401

found them. In Italy, where they had been made from native two-colored

minerals, they were even more plentiful.

Coral reefs along the African shore of the Mediterranean Sea provided

most of Europe’s coral. Coral was considered protective against lightning;

its growth in the ocean was thought to give it special properties. It was

good for children’s beads, since children needed special protection. Coral

beads were popular for rosaries and other jewelry. Coral also made early

buttons.

Fine gemstones had to be imported from the East, so they were very ex-

pensive. Medieval jewelers favored brightly colored stones: red, blue, and

green. Eastern traders brought rubies from India, sapphires from Ceylon

and Persia, emeralds from Egypt, amethyst from Russia, and turquoise from

Persia and Tibet. Some amethyst also came from Germany. Diamonds were

not as popular, or as common. Jewish and Arab traders imported diamonds

from India and Africa during the late Middle Ages, and diamonds began to

appear in some jewelry sets.

Gems were polished, not cut, until the late Middle Ages. The classic me-

dieval gem was opaque, colored, round, and smooth. Sometimes they were

engraved. In the 14th century, some jewelers were cutting simple planes

on gems. Although diamonds were the most diffi cult to cut, they benefi ted

most in appearance, and their natural crystalline shape lent itself well to

cutting.

Beads are the mainstay of much personal ornament. In addition to the

expensive gemstone or gold beads that royalty could afford, there were less

expensive options. Venice’s glass industry made glass beads in many colors,

and these grew to be among the most common for less expensive jewelry.

Amber, Northern Europe’s traditional bead, came in yellow, orange, and a

very pale yellow that was nearly white. Whitby jet made shiny black beads.

Red coral was a very popular bead material because of its protective prop-

erties. Rock crystal made a clear, sparkling, expensive-looking bead. Cheap

beads could be made of bone, stamped from a rib and polished into a round

shape. Rosary beads were originally made of pressed rose petals picked in a

special rose garden devoted to the Virgin Mary.

Early Medieval Jewelry

Byzantine jewelry blended traditions of Greece and Rome with art

brought back from the East. Their goldsmiths used gold wire and gold

plate; they set gems into place with fi ne wire claws, often shaped decora-

tively. They set emeralds, sapphires, rubies, and diamonds into gold jewelry.

They drilled and threaded pearls into settings with gold wire. They also cre-

ated mosaics in gold jewelry by setting stones such as garnets, or pieces of

colored glass, into patterns.

Jewelry

402

Constantinople was a very rich manufacturing and trading city with

longstanding aristocratic families, so the demand for jewelry was high. The

highest art went into crowns, which became increasingly heavy and elabo-

rate. Sixth-century crowns were heavy bands that encircled the head; they

were decorated with gems and had strings of pearls hanging down over

the ears. The next stage of crown was a heavy series of plates, each with a

mosaic of jewels showing a saint, that also had strings of pearls. The next

stage used an arch that went over the top of the head and was also heav-

ily jeweled. The last evolution of the crown used two heavy bands of gold,

one above the other, and, above these, a series of points standing up in the

classic crown shape used by modern cartoonists.

Byzantine aristocratic women wore large, elaborate earrings. They had

pierced ears and wore dangles, hoops, crescents, and crosses. Pearls and

gems were threaded on gold wire. Other articles that demanded gold and

gems were belts, bracelets, rings, and brooches used to pin cloaks. Reli-

gious symbols were also jeweled. A noble Byzantine woman might wear a

highly decorated, large gold cross on her chest, hung as a necklace. One

specifi c type was the reliquary: it looks to us like an ordinary large gold

cross pendant, but it contained a small box, covered by a jewel, similar to

a locket. Some tiny religious relic went into the reliquary, and it was worn

like a charm.

Before the Franks, Anglo-Saxons, Danes, and Swedes converted to Chris-

tianity, they buried gold jewelry in graves. There are treasure hoards like the

one found at Sutton Hoo, and there are more modest fi nds. Even after be-

coming Christians, Frankish royalty still went to the grave dressed in silk and

gems. They favored arm rings for men and necklaces and rings for women.

They viewed jewelry as wearable wealth and believed in fl aunting it on feast

days. Their jewelry was large and showy, but its workmanship was crude

compared to the work produced in Constantinople at the same time.

The earliest jewelry from Northern Europe comes in the form of pins and

brooches for cloaks. The Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and others made large gold

pins for these practical purposes. Saucer brooches were large gold circles

with a clasp on the back, probably for pinning a cloak to the wearer’s tunic

at the shoulders. They came in pairs, often connected by a string of amber

beads. Quoit brooches were thick circles that fastened the pin through the

hole. The other main kind of brooch is known as a square-headed brooch.

A square (or rectangle) of silver or gold was connected to a decorative

lobed cross by an arched bridge. A pin ran along the back; the bridge al-

lowed space for a woolen cloak to run through the pin. Brooches were al-

ways very decorative. They had fi ne decorations of fl owers, scrolls, dragons,

and animals, and many had amber beads mounted in them.

Europe’s medieval jewelry developed from these traditions. Italian jew-

elry was always more infl uenced by Byzantine fashions, while Northern

Jewelry

403

European work developed fi rst from large pagan pieces. As travel increased

trade in the 12th century, goldsmiths in the North began to learn from and

copy the southern pieces. By the 15th century, it was diffi cult to tell where

a piece had been made just by looking at it.

Crowns, Brooches, Necklaces, and Rings

Most medieval jewelry was made for royalty, and we have mainly these

very expensive, large, showy pieces in museums. At the same time, cloth-

ing before the 14th century was usually ample and heavy, and their greatest

need in jewelry was for pieces that fastened clothing together. Their jewelry

often came in the form of pins, brooches, and belt fastenings. They were

simple and large, with large, round gemstones. Cameos were popular and

even appeared in some crowns, alternated with gems. Cameos associated

the medieval wearer with the past glories of Rome.

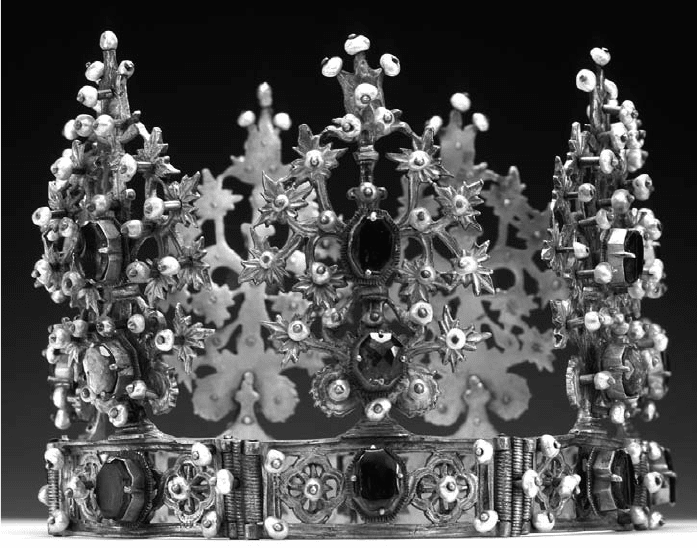

By the close of the Middle Ages, Gothic-style jewelry had become elaborate and

fanciful. A crown was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a goldsmith to show all

of his skills. Gold, silver, pearls, and glass went into this 15th-century Bohemian

crown. (Digital Image © 2009 Museum Associates/Los Angeles County Museum

of Art/Art Resource, NY)

Jewelry

404

After the 12th century, the elaborate Gothic style infl uenced jewelry

styles. The 13th century was a generally prosperous time, and jewelry pro-

liferated until kings began passing sumptuary laws. Only royalty, aristo-

crats, and large landowners and their families could wear jewels or gold.

Royal jewelry inventories from the 14th century are sumptuous beyond

modern imagination. Edward II owned 10 crowns. The mistress of his son,

Edward III, had more than 20,000 pearls. Queen Isabella of England,

married to the king in 1396, was given at least fi ve crowns and as many

brooches as gifts from the king and his lords, all covered with rubies, pearls,

sapphires, and diamonds set in jeweled gold. A French duchess owned huge

jeweled headdresses covered with pearls and every other costly gemstone.

Royal crowns grew ever more elaborate and delicate. At the same time,

the late medieval period featured complicated headdresses for court ladies,

which provided ladies the ability to wear imitation crowns without royal

status. Bands like coronets encircled their veils and barbettes. The bands

could be wide or narrow, and they gave large scope to the imaginations

of the jewelers. The headdresses themselves, made of silk, were beaded

with jewels, as were the pins, bands, and nets that held the hair tresses in

place.

The classic ring brooch remained a common form for these new Gothic

jewels. The ring was now elaborately worked in gold and set with smaller

gems in pretty patterns, such as fl owers or dragons. The brooch’s clasp was

a pin that fastened on the other side of the ring, as in Anglo-Saxon times.

Ring brooches led to heart-shaped brooches and to lobed rings like clover-

leafs or fl owers.

When a new kind of clasp, called an ouch, was developed, the brooch no

longer had to form its own way to catch the pin. New shapes were possi-

ble. Wheel brooches kept the ring shape but added gems in a center design

held in place with spokes. Brooches could also be in other shapes, such as

letters, usually M for Mary. Letter brooches were often enameled in bright

colors. Cluster brooches could be shaped like a pair of birds or a bunch of

fl owers, of course heavily covered with gems and pearls. Gems lent them-

selves well to fl owers, since one gem could be the center and the others the

petals. Hunting motifs and animals, such as stags, dogs, lions, and falcons,

were popular with royalty. As the Gothic period went on, brooch designs

only grew more fanciful: griffi ns, unicorns, squirrels, doves, harps, the sun,

eagles, swans, gardens, ladies, and even a dromedary.

Heraldic brooches came to function as badges for orders such as the

knightly Order of the Garter. The use trickled down to lesser people, whose

badges were made of lesser metals. The late Middle Ages had a fashion for

livery, a uniform dress for all the servants of a great lord, and badges were

often added, particularly in England. The earl of Norfolk’s badge was a

crowned ostrich feather, while the earl of Warwick had a bear and staff.

Jewelry

405

Badges could be made cheaply but impressively by using lead, gilding the

outside to look like pure gold.

Necklaces began as either collars or rosary bead strings. Collars were

wide, fl at links of gold or silver designs. The links were fashioned as livery

for each great lord’s household, such as a string of S links for Lancaster.

(This distinctive pattern is often called a “collar of SS.”) French collars were

made of links shaped like fl eur-de-lis, as well as other shapes such as doves

or leaves. The collar lay fl at against the wearer’s robes and had a pendant

with some signifi cant heraldic design, such as an order of knighthood. They

were royal honors, not just jewelry, and were only worn by men.

Ladies’ collars were more like fl at, wide necklaces; they were smaller and

fi t closer around the neck than the men’s and were more heavily jeweled

or enameled. Ladies had been wearing beads as rosaries for some time, and

the two styles began to blend. During the 15th century, necklaces, like

brooches and rings, broke out of the aristocracy and were imitated in less

costly style by the upper middle classes. While collars and rosaries both had

a central pendant, the new 14th- and 15th-century necklaces could fea-

ture pendants prominently as the single ornament. The heart was a popular

15th-century pendant. For the wealthy, they were gold, set with diamonds

or pearls. For the townspeople, they were silver or copper, perhaps gilded.

Crosses were always the most common pendants—jewelry that passed as a

mark of the wearer’s devotion as well as affl uence.

There were new types of jewelry at the close of the Middle Ages. Looser

sleeves in the 15th century allowed for bracelets. As with other jewelry, they

began as a fashion for royalty, set with pearls and gems. Pendants could be

fastened to the new fl oppy or tall hats to secure the folded liripipe or to

enliven plain black beaver.

In the 14th century, metalworkers refi ned and increased the production

of wire. Wire was used in headdresses and jewelry, and it began a trend of

plain gold or brass wire rings. Finger rings are ideal pieces of jewelry. They

are easily noticed on hands, and they require only small quantities of pre-

cious materials. Their simple design allows for many different ways to deco-

rate them. Plain bands can be engraved or decorated with enamel or niello to

add colors or black to contrast with gold or silver. The bezel, the raised part

on top of a ring, can be engraved or enameled or set with a gem or bead.

Although only aristocrats could wear splendid, large rings, well-off

townspeople could afford simple rings made of plainer materials. Common

rings were made of pewter, copper, brass, bronze, or even gunmetal. Fine

rings, of course, were made of gold or silver or carved from ivory. Metal rings

often had gems set in them, as modern rings do. Tiny Roman cameos were

favorite ring gemstones. A royal ring made of gold had emeralds, garnets,

or sapphires, while a common brass or pewter ring used colored glass to

imitate the appearance of real gems.

Jewelry

406

Brides wore wedding rings, and lovers gave rings as gifts. The tradi-

tions of courtly love provided the late Middle Ages with ideas for senti-

mental jewelry. Some 14th- and 15th-century rings had engraved mottoes

in Latin or French, such as “Love conquers all,” “With all my heart,” and

“Think of me.”

Rings could be the mounts for small seals, known as signet rings. They

were uncommon before the 15th century. The matrix of the seal could be

carved into a gem like onyx, or it could be engraved directly on the gold.

It was carved with the intaglio technique so that when it was pressed onto

wax, the design stood up from the surface. These rings could be less showy

than gemstone rings, but a signet ring implied importance and wealth, so a

signet by itself was an impressive piece of jewelry.

Ecclesiastical Jewelry

The Middle Ages had a special class of jewels worn, carried, and used by

the rulers of the church. Some were adornments of the church itself, such

as altarpieces and jeweled crosses. Reliquaries were among the largest, most

expensive medieval jewels; they could be as small as a ring box or as large as

a closet. Most were about the size of a breadbox. They were usually made

as miniature churches or arks.

Abbots, bishops, and archbishops wore a pointed hat called a miter,

and it was not only heavily jeweled but also could have brooches pinned

to it. Each century, miters grew taller and wider. They were made of silk

and were decorated with pearls and gems and embroidered in gold thread.

The church’s princes also wore copes, small decorative cloaks that required

spectacular brooches as clasps. The clasp was called a morse, and it was in-

variably gold or silver, with gems. The cope itself had gems stitched onto

its silk.

Even more importantly, bishops and archbishops wore rings that signi-

fi ed their offi ce. There were episcopal rings, put onto the priest’s fi nger

when he was installed in offi ce, and pontifi cal rings, used only when cele-

brating High Mass. Pontifi cal rings fi tted over gloves and were only worn on

these important ceremonial occasions. They were very large and expensive.

Ordinary episcopal rings were hardly modest. The simplest were heavy gold

with a gemstone such as an emerald or sapphire. Some had tiny reliquaries

built in, with enamel and engraved religious symbols, in addition to gem-

stones. Bishops were usually buried with an episcopal ring.

Rosary beads were a devout, sedate kind of jewelry. Originally, rosary

beads had been made from pressed rose petals grown in a garden dedicated

to Mary—a rosary. Over time, rosary beads were made of other materials:

bone, coral, pearls, gold, or gems. A rosary had 50 beads on a braided silk

string and was worn about the neck. The beads made it easier to count long

Jewelry

407

repetitions of prayers. The person praying would hold a rosary bead while

repeating the prayer and then move to the next bead. As long as his or her

fi ngers didn’t slip, there was assurance of counting correctly. They were also

called paternoster beads, and some had different-shaped beads to remind

the one praying to recite the Paternoster between the common-bead Ave

prayer, a salutation to the Virgin Mary.

Reliquaries could be built into rings or necklaces, like modern lockets.

Relics could be as tiny as a coiled hair or shard of bone. A really grand ro-

sary set for a bishop would have a small reliquary as its central pendant. Rel-

iquaries like this could be good excuses for nuns and priests to wear jewelry,

which otherwise would be considered too worldly.

Most priests and nuns were both permitted and expected to wear crosses.

Crosses, of course, could be made of simple wood, but, with time and in-

creasing donations, most clerics wore elaborate crosses. They could be reli-

quaries, of course, especially if the relic was a supposed shard of the True

Cross itself, but crosses needed no excuse to be large and gem encrusted.

Medieval crosses, whether carried on a staff or hung about the neck, are

among the most stunning, elaborate, and showy pieces ever made.

Saints inspired devotional jewelry. Goldsmiths and other metalworkers

made tiny images of saints like Saint Christopher for travelers and Saint

George for soldiers. Saints’ images could hang on a chain. There were also

diptych pendants, similar to modern lockets. Two hinged panels clipped

shut for wear on a chain but opened to show an engraved or enameled

scene of a saint’s life. Even simpler, pewter or lead pilgrim badges were re-

ligious souvenirs sold at saints’ shrines. They were mass-produced with a

mold, and pilgrims collected them as they traveled. They could fasten them

to their hats or cloaks.

See also: Clothing, Gold and Silver, Hair, Hats, Magic, Relics, Weddings.

Further Reading

Campbell, Margaret. Medieval Jewelry in Europe, 1100–1500. London: V&A Pub-

lishing, 2009.

Cherry, John. Goldsmiths. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Egan, Geoff, and Frances Pritchard. Dress Accessories, 1150–1450. Woodbridge,

UK: Boydell Press, 2002.

Evans, Joan. A History of Jewelry, 1100–1870. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications,

1989.

Norris, Herbert. Ancient European Costume and Fashion. Mineola, NY: Dover

Publications, 1999.

Norris, Herbert. Medieval Costume and Fashion. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications,

1999.

Reeves, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

Jews

408

Jews

Jews were the largest minority ethnic group in medieval Europe. For the

most part, Jews led normal lives in Europe. Their lives were more similar to

their Muslim or Christian neighbors than to each other to the extent that

climate and work shape a family’s life. Still, there were ways in which they

differed, not only in religion and holidays. Their traditions of education,

government, and family law were not the same as their neighbors’. The He-

brew language was a powerful bond tying Jews in all parts of Europe into

a common identity.

The earliest Jewish communities in Europe were in Italy, Spain, and

Germany under Roman rule. Cologne, established as a Roman colony,

had a Jewish population, living as farmers and wine producers, from the

3rd and 4th centuries. Spain’s Jews, before the Muslim conquest, also

lived as poor farmers. Muslim Spain honored Jews as physicians, schol-

ars, and administrators. In Germany, most cities had signifi cant Jewish

populations by the 11th century. Jews migrated to England and France

and also became established as small farmers, craftsmen, and merchants.

Spain became known in Hebrew as Sefarad, and Germany was Ashkenaz,

two words still used to distinguish Spanish or Arabic Jews from Northern

European Jews.

Two medieval Jews in Germany had unusual careers. A Jew named Isaac,

who lived in Aachen, went to Baghdad on a mission from Charlemagne. His

fellow ambassadors died on the journey, and he became both survivor and

leader. His most famous task was fi nding a way to escort a white elephant

over the Alps, along with the many other rich gifts from Caliph Harun

al-Rashid. Later, in the 14th century, Süsskind von Trimberg was one of

the Minnesingers, the German troubadours. He traveled like a Christian

minstrel until he was forced to wear a distinctive Jewish badge.

Many European cities had a Jewish Quarter, a voluntary neighborhood

cluster of Jewish artisans and merchants. The location became less volun-

tary and more restrictive as Europeans became more prejudiced against

Jews. Then Jews lived in the Jewish Quarter because they were legally re-

quired to live there.

Jewish men wore full, untrimmed beards that made them look differ-

ent from their Christian neighbors. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council

declared that Jews and Muslims must also wear distinctive clothing or a

badge. The distinctive badge varied from place to place. The most common

was a fl at, funnel-shaped hat with a tall point. Some medieval illustrations

of Bible scenes with Abraham or Moses show the patriarchs wearing these

Jewish hats. In other places, they wore a yellow stripe or a square yellow

hat. During the 14th century, at the height of anti-Jewish prejudice, some

places required Jews to wear a red and white circle on their chest. After the

Jews

409

close of the Middle Ages, the most common badge became a yellow ring

stitched to their cloaks.

Houses

Jewish houses were similar to Christian European houses, but there were

some distinct differences. The home was the center of Jewish religious ob-

servance, even more than the synagogue. To some extent, Jews fi t into the

culture they were in: in Muslim Spain, their houses had beds on the fl oor,

while they had wooden platform beds in Germany. In Spain, the most im-

portant function of the garden was to have a cooling fountain; in France,

it was to have an adequate well and privy. In Spain, they often had separate

sleeping and dining rooms, but in the small houses of France and Germany,

they slept in one room and ate in the kitchen. Jewish homes in Spain often

had small water clocks by the 13th century, and there were prominent Jew-

ish clock makers in the Arabic water-clock tradition. There was a greater

tendency for Jews to build houses of stone in cities where Christian houses

were still typically wooden.

There were a few key differences that crossed all regions. Every Jewish

house had a miniature Torah scroll called a mezuzah mounted in a special

case on the right-hand doorpost. It contained some lines from the law and

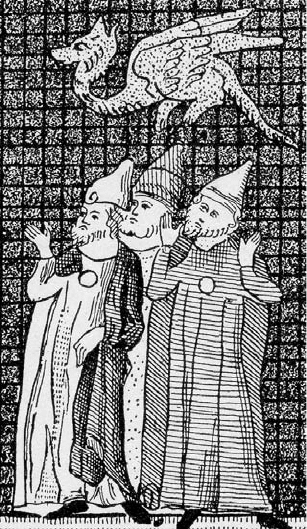

Jews were offi cially viewed as foreigners,

even if their families had lived in the town

for many generations. Unless they converted

to Christianity, they were in a special class

of people with foreign loyalties who needed

to be watched. After the Fourth Lateran

Council of 1215, Jews in Europe were

required to wear badges to prevent them

from blending in. Pointed hats and yellow

badges, shown here in a 14th-century Bible

illustration, were the typical French

requirement. (Isadore Singer, ed., The Jewish

Encyclopedia, 1901)