Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Tools

690

heads. They used square iron nails and long iron staples made from thick

bent wire.

The boom crane evolved from the simple use of pulleys to raise heavy ma-

terials to the level where builders were working. The simplest kind was a pole

with an arm bearing two pulleys; a rope went over the pulleys and dropped

to the ground. A simple lifting device like this was called a falcon or hawk.

The real breakthrough in raising heavy blocks of stone came with a giant

treadwheel. This large wooden wheel fi t several men inside, and they walked

to move the wheel; its power could lift much larger loads. To strengthen the

frame, instead of a vertical pole with a horizontal arm, builders leaned a

stout log against a shorter pole, forming a triangle on the ground with a

tall diagonal arm leaning out. The windlass, or crank, came into use in the

15th century. Used with simple cranes, a windlass could lift heavier loads

than a man’s arms could pull on their own.

The crane could be used for lifting or pounding. It could be a pile driver

that pounded logs into soft ground like nails to create a fi rmer foundation.

In this case, the crane lifted a very heavy block of wood and then let it drop

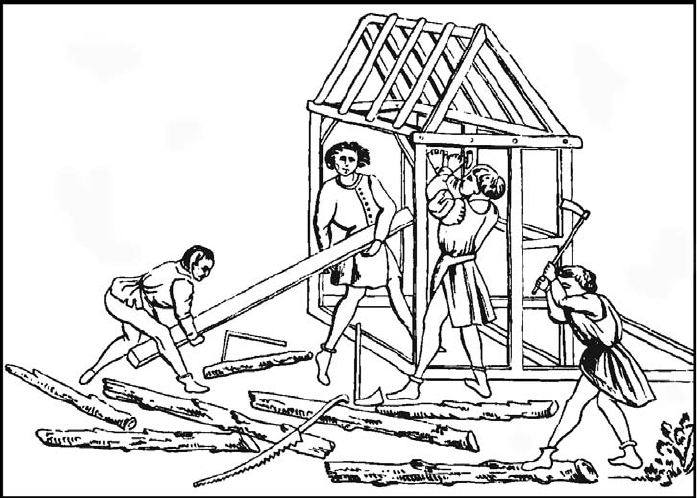

Basic carpentry tools have not changed much over time. Even in a time of power

tools, carpenters still depend on L-squares like the one sitting on the ground. These

medieval carpenters are using axes and saws to square off tree trunks as usable lumber.

While the building in the illustration is too small to be a real building, house size was

limited by the length of local tree trunks. (Paul Lacroix, Moeurs, Usage et Costumes au

Moyen Age et a l’Epoque de la Renaissance , 1878)

Tournaments

691

on top of the log. For lifting building materials up to masons, bricklayers, or

carpenters, they used a basket or tub with handles, tied to a rope. Stone blocks

were lifted with a clamp called a lewis. In some cases, the stone had a set of

depressions chiseled into the top so that the tongs of the lewis would fi t into

them. In other cases, the lewis was shaped like scissor tongs and suspended

from a rope. When it was clamped around the stone block, the pull on the

rope exerted more pressure on the tongs to remain closed, thus gripping the

block securely.

Workmen had to go up and down the unfi nished buildings using ladders

and scaffolding. The standing platform of scaffolding was usually made of

wattle (pliant branches woven together) because it was lighter and cheaper.

Scaffolding could be built up from the ground in the form of poles lashed

together to support the platforms. Castle building tended to use built-in

scaffolding, particularly for round towers. As the tower rose, poles were built

into the walls going upward in a spiral. When the tower was complete, the

scaffolding was removed, walking backward down and pulling the poles out

of the wall. Some towers still have these holes, and some still have pegs or

poles that were left in case they were needed later for repair. The least com-

mon kind of scaffolding that was necessary in some cases was a hanging wat-

tle platform, suspended from a crane or tower to lower workmen to the

building site.

Medieval workmen used only one kind of safety equipment. When they

were working at great heights, installing stone blocks for a vaulted ceiling,

some tied a rope around their waist and secured it to a column. Not every-

one did this, and it was the only safety measure known. Work accidents were

as routine as accidents in other areas of life.

See also: Castles, Cathedrals, Forests, Houses, Iron, Stone and Masons.

Further Reading

Binding, Gunther. Medieval Building Techniques. Stroud, UK: Tempus Publish-

ing, 2001.

Coldstream, Nicola. Masons and Sculptors. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

1991.

Harvey, John. The Master Builders: Architecture in the Middle Ages. New York:

McGraw Hill, 1971.

Harvey, John. Mediaeval Craftsmen. New York: Drake Publishers, 1975.

Hislop, Malcolm. Medieval Masons. Botley, UK: Shire Books, 2009.

Tournaments

The festival war games called tournaments fi rst appear in the written re-

cords of Northern Europe around the year 1100. Real wars were at a lull;

Tournaments

692

the barbarian Vikings and Huns were no longer a problem, and the Hun-

dred Years’ War between England and France had not yet begun. The First

Crusade had been launched in 1095, but many knights had returned

home, bored. Tournaments provided employment and entertainment for

those not on Crusade. The object of a tournament was to capture, not

kill, the opposing fi ghter. Losing knights paid ransoms to winning knights,

which made tournament skill a possible source of income.

Since the time of Charlemagne, knights had sometimes staged mock bat-

tles for training. When there was no war, young knights had to be tough-

ened up by facing danger and being injured. Tournaments made training

into a sport. During the 12th and 13th centuries, the main feature was a

large mock battle, the melee. Far more than any other sport, tournaments

were violent and caused severe injuries. Knights went into the fi eld as well

armored as they were in battle, and although they often used blunt weap-

ons, the violence was still savage.

Tournaments, unlike war, had strict rules. There were judges and her-

alds to register (or disqualify) all invited and uninvited participants. There

were fenced zones where injured knights were safe from attack in a melee.

These may have been originally called the lists, a word that later came to

apply to the jousting fi eld itself. It was a foul to aim for the other knight’s

horse; the result was disqualifi cation. One knight was chosen as a fi eld ref-

eree, called the chevalier d’honneur. His lance had a headscarf pinned to it,

and he could go to any knight in distress and touch him with it, disallow-

ing any further attacks. A melee could continue only until the president of

the tournament, the offi cial in charge, decided to throw down his warder as

a signal to the heralds. Then the heralds’ trumpeters sounded retreat, and

the fi ghting had to stop.

When a knight unhorsed his opponent, he claimed the loser’s armor

and horse. The loser nearly always ransomed them back; if not, the winner

could keep or sell the equipment. Ransoms were fi xed in advance; the price

rose with a knight’s rank. In this way, a poor but talented knight could be-

come wealthy by playing the tournament circuit. Knights errant, who came

from noble families that had lost their wealth and land, earned a living by

jousting. Tournaments were a very expensive game for those who were not

as talented; the average knight only entered the lists to the point that he

could afford the losses. The biggest loser in a tournament would be a high-

ranking nobleman, such as a count or even a king, who was a poor con-

tender and only incurred losses that cost him high ransoms.

Tournaments always offered prizes, paid for by the sponsor or by aris-

tocratic spectators, usually ladies. The most common type of prize was an

animal, such as a dog, a falcon, a bear, or even a sheep or a large fi sh. Tour-

nament records also tell us that some prizes were gilded statues of animals

Tournaments

693

like deer, falcons, or horses. It is possible that the ladies who sponsored the

prizes acted as judges. The tournament always closed with a feast at which

the winners were honored at the high table.

Knights who made a habit of attending most tournaments in a circuit

across France, Flanders, and England traveled many miles with large reti-

nues of servants and horses. When a band of knights traveled together,

each with his spare horses, pack animals, squire, and other servants, the

group was not only large but also rowdy. They were a notorious roadside

hazard to other travelers, with whom they were too eager to get into quar-

rels. At times they robbed less powerful travelers. This tendency of knights

to use their power too freely was a primary motivator of the code of chiv-

alry, which insisted that they must never rob, rape, or bully a weaker party.

During the 12th century, the kings of England and France, and some

other ruling lords, opposed tournaments as violations of their decrees of

peace. Counts and princes who liked the danger and excitement of tourna-

ments continued to sponsor and organize them, often at outlying fi elds on

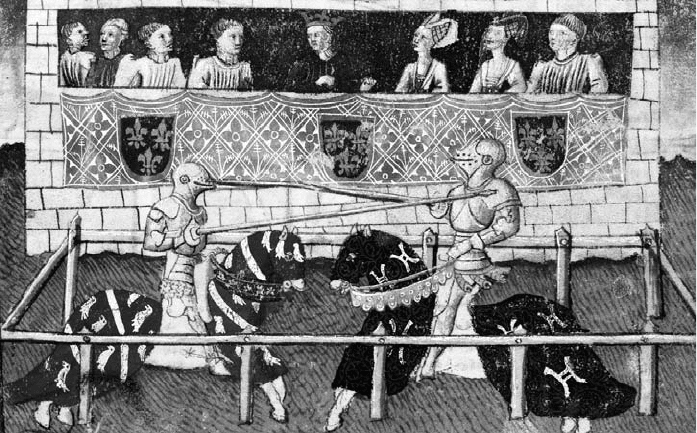

By the 15th century, tournaments had become more sport than war training.

Everything was formalized: the spectators had sheltered seats and included fi ne ladies,

and the joust only took place in a guarded area called the lists. Each contestant and

some of the spectators can be identifi ed from his heraldic symbol; the artist did not

need to add names. Although the lists were enclosed with a low fence, the area must

have been much larger than shown here. In many later tournaments, the jousting

knights were separated by a low wall that kept them in lanes. (Royal Armouries/

StockphotoPro)

Tournaments

694

the border of two realms. The “Young King” Henry, son of Henry II of

England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, was a big sponsor and participant in in-

ternational tournaments. He kept a team of knights as paid staff to fi ght in

melees and paid the ransoms when they lost. Aggressive, free-spending aris-

tocrats of this type made the tournament the fi rst-ranked interest all across

Northern Europe. There were cases of bored knights in besieged towns or

castles challenging the besieging army to a tournament outside the walls.

In most cases, both sides respected the rules, and then went back to their

war stations when it was over.

The church at fi rst opposed tournaments as festivals of pride and vice

and as opportunities to sin by killing, even accidentally. If a man died in a

tournament, he was considered a suicide, since he had put himself in harm’s

way. Some bishops excommunicated tournament participants, but wealthy

knights bought their way back into grace by giving alms or donating land

to the church. Tournaments were so popular among the nobles of England,

France, and Germany that the church’s opposition made no difference.

People loved tournaments, where courage and skill could be seen close up

without the danger and confusion of a real war. By the time minstrels were

circulating stories of the Virgin Mary disguising herself as a knight, moral

opposition had no effect, and the church stopped opposing tournaments.

Aristocratic women came to tournaments as spectators. By the 12th cen-

tury, their role in public had changed, and the new spirit of courtly love

encouraged knights to fi ght better to impress the women. Ladies chose

champions and gave favors and were prominent guests in the viewing stands.

Some ladies learned to joust, and by the 14th century, when knights began

to come in costumes, some ladies came costumed as men. Their clothing

fashions were also infl uenced by heraldry ; the cotehardie often bore em-

broidered heraldic arms so that the ladies could attend the games dressed

like modern sports fans, in team colors. A few bold ladies grew so infatu-

ated with tournaments that they began traveling from one to the next, in-

stead of attending only those closest to home.

Tournaments fi lled nearby towns with participants, spectators, mer-

chants, craftsmen, and horse thieves. When a knight could fi nd a house

to rent, instead of staying in the fi eld in his tent, his squire hung his ban-

ner or shield in the window of the rented rooms. Local castles and manors

permitted friends and other participants to stay, and visiting kings generally

stayed at these castles, rather than in tents. In the tournaments where towns

served as headquarters for regional teams of knights, halls and kitchens

were rented for receptions and feasts. There was usually a trade fair asso-

ciated with a tournament, and merchants and craftsmen for tournament-

related business set up booths. Some armor makers became itinerant armor

menders, following knights on the circuit. The event was also a big oppor-

tunity for local merchants to sell more food and other provisions.

Tournaments

695

The nature of tournaments changed during the fi ve centuries when they

were popular. Early tournaments of the 12th century had both single-combat

challenges and a mock battle—the melee. In single-combat challenges, un-

horsing the opponent meant victory and the right to claim a ransom. In

the melee, the knights were assigned to opposing armies, and they charged

each other at a given signal. Although the object was to capture opponents,

many knights were seriously injured or killed in melees. In early tourna-

ments, the mock battle was not formalized or confi ned to the fi eld at hand.

A group of knights could veer off the fi eld and chase into nearby woods

or fi elds. These large mock battles brought out hundreds of knights, and

some large 12th-century tournaments claimed to have more than 1,000

participants.

The 13th century may be considered the height of the tournament.

Each event, now formalized with traditional rules, lasted about a week.

The knights began with some days of practice jousting, and then held for-

mal jousting challenges. While the original meaning of a joust was any kind

of single combat with any weapons, by the 13th century it meant only the

combat when knights rode against each other with lances. Fights could be

to the death (or until injury or surrender), or they could be just for points,

like a game. If the lances and swords were blunt, they were called “arms of

courtesy.” After a day of rest and paying ransoms, the knights chose sides

for a melee. The mock battle was held in a more restricted area, a fi eld

rather than the general countryside as in the previous century. The last day

was for feasting, dancing, and minstrel performances.

In the late 14th century, tournaments began to have as much pageantry

as warfare. In some English tournaments, the knights wore costumes onto

the fi eld. They fought as monks or even as cardinals. At the opening day

of another tournament, the knights paraded onto the fi eld, each held with

a silver chain and led by a lady on a horse. In a French tournament of the

middle 15th century, the participants dressed as shepherds. There was a

trend away from full armor and real weapons; some places ruled that only

partial armor could be worn, and even squires could not bring so much as

a dagger.

By the 15th century, tournaments had completely changed. There were

no dangerous melees, and the single combats were very formal and styl-

ized. Battlefi eld fi ghting no longer used lances, so training with a lance

was only for a tournament. Armor had become very heavy, as it was made

entirely from plates of metal. It was less necessary and more ceremonial,

often covered with decorative etchings and used mostly in parades. Horses

were larger and slower, and saddles were improved to the point that knights

could not always be unhorsed. Knights rode against each other with a low

wall, called the tilt, between them. Contestants won on style points given

by judges.

Tournaments

696

Tournament Equipment

During the height of the tournament’s popularity—the 12th and 13th

centuries—chainmail hauberks were the usual armor. There were also

tournament-specifi c fashions. Some knights wore peacock feathers or fl ut-

tering ribbons or straps on their armor, and knights at tournaments always

wore the most colorful fashions in surcotes. Squires wore lighter armor,

such as padded tunics and lighter hauberks called haubergeons. During the

13th century, squires began to dress more like knights, and knights wore

ever more elaborate attire.

In the 14th century, the development of plate armor for the battlefi eld

brought it into the tournament. From that time, tournaments drove the

development of armor as much as war. Horses did not need armor in a

tournament, but plate armor for the horse’s chest developed in response to

pike warfare. Equine armor looked impressive and was very expensive, so in

the later tournaments of the 15th and 16th centuries, it was often used.

By then, the knight’s tournament armor had diverged from war armor.

It had lance rests built in, and the side turned toward the oncoming lance

was more heavily padded and plated. Special plates defl ected lance blows at

points of frequent contact. Some regions developed padded leather shock

absorbers. Tournament armor by the end of the 15th century was not un-

like a heavily padded football uniform. German armor makers had become

dominant in Europe at this time, so the German tournament style also

became dominant. It was heavy, expensive, and extensively decorated and

gilded. By the 16th century, tilting armor had become highly specialized.

The helm developed for tournaments by the 15th century was impracti-

cal in war. It was pointed in front to defl ect lances, and the entire face was

covered. A slit permitted the knight to see only in front of him, and only

when his head was tipped forward. In a single-combat joust, the knight

could focus only on the threat in front of him.

A lance used in a tournament was different from a lance used in war. It

had no sharp point; instead, it had a blunt end with three iron fi ngers stick-

ing out to allow the knight to push on the other knight’s armor and throw

him from his horse. Originally, the shaft of the lance was just a 14-foot

pole, but by the 15th century, the grip end had been specially designed for

tournament use. The knight’s breastplate had a bracket riveted to the right

side to help hold the heavy lance. The lance was thicker at the handle end

to transfer the center of gravity back toward the knight’s hand. The handle

had been carved out of this thick end, so the thicker part formed a guard

for the hand.

The lance was held under the right arm, against the body, which made

it cross over to the left side of the horse’s neck, sticking out in front. The

knight aimed at his opponent’s head or body, and he had to hold the lance

Tournaments

697

as fi rmly as possible, pointing straight forward. At the moment of impact,

he rose in his stirrups and pushed forward with his body’s weight. At the

same time, he had to duck or defl ect his opponent’s blow.

The knight’s tournament saddle had a high back and a high, wide pom-

mel called a burr plate. Even more than in battle, in a tournament the

oncoming lance could slip and strike the knight’s saddle or leg. Since the

point of jousting was to remain in the saddle, it held the knight with great

stability. Stirrups had to be very strong, and they were designed to avoid

trapping a knight’s foot, in case he did fall.

Tournament weapons became increasingly ceremonial as the Middle

Ages passed. Blunt swords used as arms of courtesy could still hurt some-

one; at times, whalebone swords were used. With whalebone swords, leather

armor was adequate. A combat of this type was truly sport, rather than war.

With the increase of pageantry and show over the centuries, tournament

equipment included heraldic fl ags, caparisons for the horses, surcotes, and

tents. A knight needed many wooden lances and at least two swords and

shields. He needed at least one spare horse. His squire stayed in the tent

with him and helped him dress, and they needed their supplies for the

week. Additionally, both knight and squire needed fi ne clothes for the fi nal

banquet.

See also: Armor, Feasts, Heraldry, Horses, Knights, Weapons.

The late-developed helmet for jousting

was very impractical for real warfare. In

a tournament, the knight knew exactly

where his attacker was and could

sacrifi ce visibility to face protection. He

could only see out through the slit

when his head was lowered to charge.

(Royal Armouries/StockphotoPro)

Tournaments

698

Further Reading

Barber, Richard, and Juliet Barker. Tournaments: Jousts, Chivalry, and Pageants in

the Middle Ages. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2000.

Barker, Juliet. The Tournament in England, 1100–1400. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell

Press, 2003.

Charny, Geoffroi de. Jousts and Tournaments: Charny and the Rules for Chivalric

Sport in Fourteenth-Century France. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Book-

shelf, 2003.

Clephan, R. Coltman. The Medieval Tournament. Mineola, NY: Dover Publica-

tions, 1995.

Crouch, David. Tournament. New York: Hambledon, 2006.

Oakeshott, Ewart. A Knight and His Horse. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions,

1998.

Oakeshott, Ewart. A Knight and His Weapons. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Edi-

tions, 1997.

Toys. See Games

Troubadours. See Minstrels and Troubadours

U