Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Universities

701

Unicorns. See Monsters

Universities

In medieval times, a center for advanced study was called a studium. Stu-

dents, who already could read and write Latin, listened to lectures in Latin.

The entrance exam was typically a test of ability with Latin. Students stud-

ied the liberal arts curriculum of rhetoric, mathematics, and grammar.

Rhetoric was the main fi eld of study, as they studied arguments and philo-

sophical questions. After the main course of study had been completed,

students could choose to study medicine, law, or theology, depending on

the strengths of each university.

The fi rst university was at Bologna, Italy, and its specialty was the study

of law. Next were Paris and Oxford, both centered originally on theology as

well as law. Paris and Oxford were under church oversight, while the uni-

versity at Bologna was independent. Medical schools could be independent

of universities, as at Salerno, or they could be part of a larger institution, as

at Pisa and Milan. By the 14th century, most cities had a university.

The bedellus in a medieval university was the offi cial responsible for keep-

ing classes running, like a modern dean. In Paris, a teacher was called mag-

ister, while in Bologna, he was called doctor. Although university scholars

did not have to be ordained clergy, they were often in orders. If they were

not, they were expected to live as monks and devote themselves only to

learning. The Dominicans and Franciscans came to dominate teaching in

the universities during the 13th century.

Lecturers at early universities were paid directly by students, who con-

tracted to hear them lecture on their specialty subject. The word university

came from the Latin expression for associations of students and teachers,

universitates scholarium and universitates magistorum, who used collective

bargaining to negotiate the terms of study. Students demanded that teach-

ers meet certain standards, such as being in class on time and not lectur-

ing past quitting time. At Bologna, they forced the masters to promise to

start and end their lectures on time or pay fi nes. Instructors were required

to cover the promised curriculum, and they could not be absent without

permission from the students. On their side, teachers demanded standard-

ized fees. These collective-bargaining associations became the name of the

institution whose customs they shaped: the university.

General university subjects were logic, rhetoric, music, astronomy, arith-

metic, and geometry. Logic received the most attention; it expanded to

include all the works of Aristotle, which included studies of science and

ethics. A standard method of teaching was an oral debate over a question

proposed by the teacher. The students took part in the debate and based

Universities

702

their arguments on their reading. An opening topic might be, “Whether

lightning is fi re descending from a cloud.” The fi rst stage consisted of ar-

guments to the affi rmative, called the principal arguments. Then other stu-

dents (or the teacher) provided arguments to the negative, contradicting

one or more of the principal arguments, and usually citing an authority

such as Aristotle. The format allowed university students to hear their study

put to use and to sharpen their wits about how to reason and debate.

In order to produce textbooks for the students, the university sent work

to outside copyists. After the professors created an exemplar of a short text,

private copyists, including educated women, made copies by hand. These

simple copies, called in Latin pecia, could be made quickly and inexpen-

sively. Students could buy or rent them. Because these short books were

intended for student use, they were unlike any other medieval books and

much more like modern ones. They had wide margins for taking notes in

class, and they divided the text into paragraphs and red letters (rubrics)

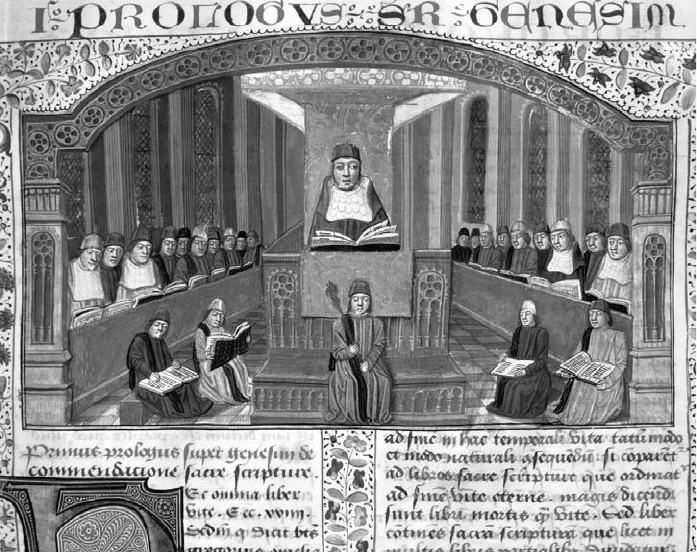

University lectures were often given in much simpler rooms than this fi ne paneled

hall at the Sorbonne in Paris. The format was generally the same all over Europe:

a lecturer spoke in Latin as students studied the text and took notes. Debates

provided the only variety. (© Glasgow University Library, Scotland/ The

Bridgeman Art Library)

Universities

703

that broke up the text. They also put spaces between words to make them

easier to read.

Completion of the general university course took between 4 and 6 years.

After this, students could study law, theology, or medicine. Each university

developed a specialty. Theology was the specialty of Paris, to the deliberate

exclusion of other graduate studies, so that theology students would not

be distracted. The university at Bologna had a medical school that allowed

students to witness the dissection of cadavers, but medical students at Ox-

ford did not witness dissections. Many medical faculties at universities did

not incorporate patient care, but required only memorization of standard

texts. A medical degree might be earned in 8 years, while a theology degree

required at least 12.

On completing the degree, the student had to apply to actually receive

it, and this application cost a substantial fee that provided a great part of

the university’s funding system. Some students could afford to attend the

university, but they could not afford to graduate. The most common title

granted on graduation was “master.” This title permitted the graduate to

teach. “Doctor” also indicated “teacher” and was used in some universities

as the teaching title. It was gradually applied to physicians, since they were

very learned.

The organization of colleges within a university came about as a solu-

tion to housing for students who were often as young as 15 and were far

from home. A college was a small community to support these students’

living needs. Many of the fi rst colleges were endowed by a patron so that

the students enrolled there would say prayers for the patron’s soul; the col-

lege provided room and board in exchange. These early colleges often gave

preferential acceptance to poor relatives of the founder, and some began to

require work, as partial payment, from the poorest students. The Sorbonne

began as a charitable boarding house for poor theology students and only

later added teachers to become a real college. The colleges of Oxford began

similarly.

By the late Middle Ages, colleges maintained a cook and a laundress.

A manciple oversaw the college’s operations, and larger colleges began to

employ tutors to help their resident students. As books were donated, col-

leges built up libraries. College rules helped regulate student behavior;

since most students lived at the college free of charge, the college could

require attendance at Mass or at university lectures, and it could expel

those who were too unruly. Students who lived on their own could easily

turn into petty criminals or vagabonds, so the college system of organiza-

tion helped make university study respectable again. By the end of the pe-

riod, some students were paying to live at colleges, but it was considered

more of an honor to have been admitted for free, on merit. The colleges

were the fi rst real dedicated buildings at most universities, which generally

Universities

704

rented their lecture halls and only built or purchased buildings after the

Middle Ages.

Students were typically unruly. They considered themselves to belong

to the university, rather than to the town. They insulted students or trav-

elers of other nationalities and got into violent fi ghts. They gambled and

drank. It was unclear whether they had to obey the town’s laws or whether

they were answerable only to the university. When a student occasionally

committed a violent crime, the town and university came into confl ict. At

Oxford in 1355, a fi ght at a tavern led to a riot the following day in which

some students and townspeople were killed, and some college buildings

burned. The usual redress for these riots was in favor of the university, since

the kings had a keen interest in keeping the universities open. It was easier

to discipline the town.

During the medieval period, many masters and lecturers began to wear

distinctive robes and hats to show their academic status, just as other pro-

fessions and guilds had distinctive clothing. The robes and beret-like caps

were originally identical or similar to the robes and caps of the clergy, since

many of the lecturers were monks. The variations on these robes and caps

through the late Middle Ages and Renaissance became the modern cap and

gown of graduation. At the University of Paris, by the mid 14th century,

doctors of theology wore black robes, often with matching hoods. Doctors

of law wore red robes with wide sleeves. At the Italian universities, scholars

wore red robes edged with miniver fur.

See also: Books, Medicine, Music, Numbers, Schools.

Further Reading

Frugoni, Chiara. Books, Banks, Buttons, and Other Inventions from the Middle Ages .

New York: Columbia University Press, 2003

Gordon, Benjamin L. Medieval and Renaissance Medicine. New York: Philosophi-

cal Library, 1959.

Grant, Edward. Science and Religion, 400 B.C. to A.D. 1550: From Aristotle to Co-

pernicus. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Haskins, Charles. The Rise of Universities. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers,

2001.

Newman, Paul B. Growing Up in the Middle Ages. Jefferson, NC: McFarland,

2007.

Ridder-Symoens, Hilde, ed. A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1, Universi-

ties in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

W

Wagons and Carts

707

Wagons and Carts

The most ancient form of animal transportation, which was used all over

medieval Europe, was the pack. Roads were often no better than narrow

paths, and where bridges existed, they were rarely wide enough to allow

a wheeled vehicle to pass. Most farm products and peddled goods were

moved in packs on oxen or mules. Wheeled vehicles had been used in Eu-

rope since Roman times, but they only expanded in use as roads improved.

During the early Middle Ages, the old Roman roads decayed; new towns

and cities did not build good roads, but allowed paths and tracks to widen

into dirt roads. Wheeled transportation increased, but it was never as im-

portant as shipping by water during the period. Its importance was mostly

local and personal, in the form of simple carts. There were always places

where wheels were impracticable. In winter, or in very steep places where

more friction with the ground was helpful, sledges were also used.

By the Middle Ages, the wheel had developed into the stable form still

in use today for many farm carts. Spokes made of oak attached to an elm

hub, also called a nave or stock. The spokes were hammered into curved

beech or ash pieces called felloes, which fi tted like puzzle or arch pieces

into a wheel shape. In the earliest wheels, thin wood pieces called strakes

were nailed around the outside of the felloes to form the rim. Additional

nails, left sticking out a bit, could give the wheels more traction. After iron

technology became common, iron rims were standard. A band of iron ran

around the outside rim; it was applied while hot so that it would shrink as it

cooled and create a very tight fi t. All through the Middle Ages, the earlier

technique of nailing wooden strakes around the wheel remained very popu-

lar. A farmer or carter could repair this wheel himself if needed.

Wheels properly attached to a cart or wagon were set at an angle, called

dishing, to counterbalance the swaying of the animal’s movement, the

shifting of the load, and especially the uneven road surface. The axles were

set so that the top of the wheel leaned away from the cart. Early axles were

made of oak and attached the wheel with a wooden linchpin. Iron axles

were stronger than wooden ones and replaced wood in more expensive and

durable carts in the later Middle Ages.

Harnesses for both carts and wagons were most often made of leather,

but they could be made of cloth. The most expensive piece of the harness

was the horse’s collar, which had a wooden framework inside the padded

leather covering. Halters, traces, girth straps, and occasionally saddles made

up the rest of the kit.

The fi rst form of wheeled vehicle was a two-wheeled cart. During the

Middle Ages, the two-wheeled cart was much more common than the four-

wheeled wagon. Two wheels suffi ced to carry the load, and a two-wheeled

cart was easier to maneuver on a deeply rutted road or track. They could be

Wagons and Carts

708

used with an ox, a donkey, a small horse, or even the peasant’s own muscle

power. Additionally, a two-wheeled cart easily acted as a dump truck. Carts

could haul manure, hay, or wood, and if the cart was unhitched from the

animal at the destination, it tipped back to dump the load. No medieval

carts have survived into contemporary times; the cart was a working piece

of equipment that remained in service until it fell apart.

Two-wheeled carts were able to manage all but the heaviest farm loads.

For hauling hay or grain at harvest, a large cart could be loaded heavily

and hitched to more than one ox or horse. The cart’s shafts connected to

the closest horse, with one or two horses in front, their heavy collars con-

nected by ropes to the shafts. The heaviest, largest carts were called plaus-

tra in Latin and may have been used primarily with oxen. They were heavily

loaded with hay but still had only two wheels.

Carts acted as common transportation not only within farms and vil-

lages, but also from the farm or village into the market town or city. Two-

wheeled carts carried the majority of goods to and from the point of sale.

Carts carried into cities loads of charcoal, cheese, bread, nuts, pottery jugs,

candles, fi rewood, and fl our. It is hard to name any commodity that was

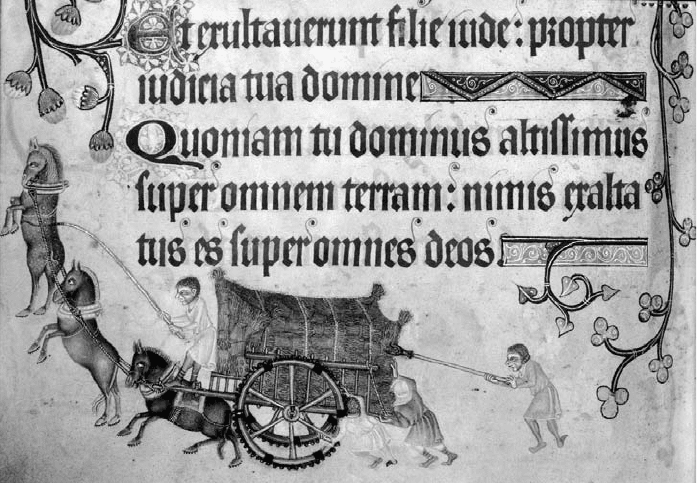

Two-wheeled carts carried most farm products around Europe, since they were

cheaper to make and easier to maneuver on turns. The picture shows a heavy covered

cart turning to go up a hill. The horsepower is not quite suffi cient and a team of

farmhands must help push it and keep its load from falling out. (The British Library/

StockphotoPro)

Wagons and Carts

709

not carried by carts, which hauled water, manure, rubbish, gravel, chalk,

lime, building stone, brick, timber, and all kinds of produce and manufac-

tured goods.

Carts were as often hired as owned. Farmers owned carts, as did manu-

facturers who used them for transport every day, but most people in a town

did not. Just as horses could be hired, so could a cart and ox. Royal offi -

cials could often press private carts into service at a moment’s notice. Some

carters also made regular journeys between large towns and cities, carrying

packages and goods for people who did not transport things enough to

warrant the use of a whole cart. These private carriers operated as a regular

parcel delivery service.

Carts required frequent upkeep. Wheels and other parts had to be lubri-

cated regularly, and about every year, the axle wore out and had to be re-

placed, particularly if it was an old-fashioned wooden axle. A heavily used

cart ran through two or three sets of wheels in a year. Depending on its

use, the body of a cart lasted a year or two before it needed to be replaced

or fi xed.

A wagon is, by defi nition, a box with at least two axles and four wheels.

Wagons were common on the European continent during the Middle

Ages, but not in England. Many of England’s roads were inadequate for

wagons until the 16th century. Wagons were a greater fi nancial investment;

a wagon cost more initially than a cart, and it required the upkeep of four

wheels and two axles. It was used to pull heavier loads and usually needed

multiple oxen or horses, a further expense. Wagons were used for heavier,

longer distance transport, such as moving household goods over long dis-

tances. When nobles traveled between their castles and manor houses,

they used wagons to move their furniture and supplies. They were called

currus in Latin household records, which became car, char, and charet in

15th-century English. Wagons were more expensive and less common and

were less likely to be worked until they fell apart, so a few old wagons have

survived.

During the 12th century, wagon technology took some steps forward.

First, the oxen or horses were connected with a set of double shafts (wooden

poles) around the animal’s body. The double shaft attached to the horse

collar or oxen yoke so that the animal’s shoulders pulled equally on the

load. In the next stage, the shafts were connected not to the wagon directly,

but to a whippletree. The whippletree was a bar in front of the wagon; it

received the direct pull of the animals and was connected to the wagon at

only one point. It was mounted on a pivot so that the animals could turn

and the wagon would follow.

Next, the development of an undercarriage that could turn the front

wheels made wagons much easier to use but harder to build. The front axle

had to be mounted on its own framework that was independently attached