Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN258

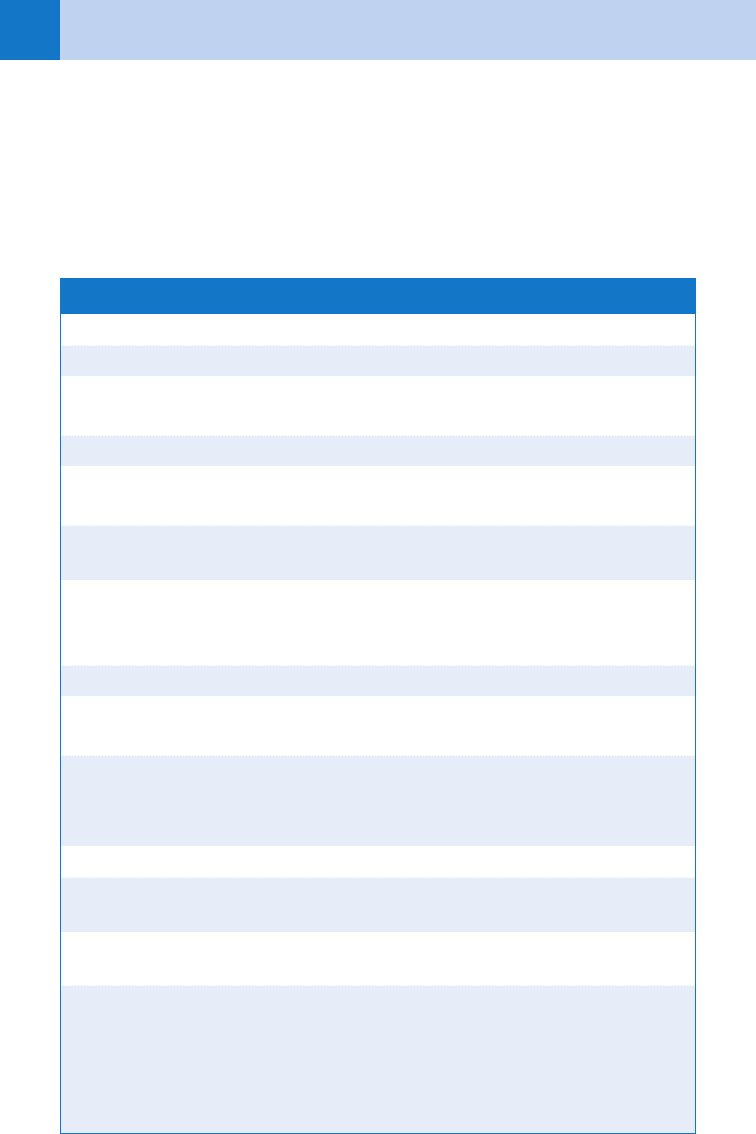

Opioid analgesics

Anileridine (Leritine) PO 50 mg q 4 h prn

Hydromorphone IV 1–2 mg q 2–4 h

IM 1–2 mg/kg q 2 h prn*

Meperidine (Demerol) IV 25–50 mg q 5–10 min prn

Morphine sulphate IV 3–5 mg q 5–10 min prn

IM 0.1–0.2 mg/kg q 3 h prn*

Oxycodone and acetaminophen

(Percocet)

PO 2 tabs q 4 h prn

Oxycodone and acetylsalicylic acid

(Percodan)

PO 2 tabs q 4 h prn

Antiemetics

Metoclopramide (Reglan) IV 10–20 mg q 15 min prn

Perphenazine (Trilafon) IM 5 mg q 6 h prn*

PO 4 mg q 6 h prn

Prochlorperazine (Compazine) IV 5–10 mg q 4 h prn

IM 5–10 mg q 6 h prn*

PO 5–10 mg q 4 h prn

Nonsteroidal analgesics

Diclofenac (Voltaren) 50- or 100-mg suppositories,

150 mg/day

Indomethacin 50- or 100-mg suppositories,

200 mg/day

Ketorolac (Toradol) IV 30 mg q 6 h

IM 30 mg q 6 h

IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, per os (by mouth); prn, as needed; q, every.

*Intramuscular route not recommended for ED management of acute, severe pain.

21. What are the basics of ED treatment of renal colic?

Hydration, analgesia, and antiemetics. Patients who have clinical dehydration secondary to

vomiting and decreased oral intake, as well as if radiocontrast media study is planned, should

receive intravenous fluid hydration. Various analgesics and antiemetics are available for rapid

control of symptoms (see Table 36-1). Intravenous pain control is the mainstay of ED

treatment. Analgesic treatment should not be delayed waiting for test results. Opiate

analgesics have long been the standard medication. Rectal or intravenous nonsteroidal

TABLE 36–1 ANALGESICS AND ANTIEMETICS FOR RENAL COLIC

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN 259

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit renal prostaglandin synthesis, are effective

and may be given concurrently with opioids. A recent systematic review suggested that for the

management of acute renal colic, NSAIDs achieve slightly better pain relief, reduce need for

rescue analgesia, and produce much less vomiting than do opioids. Optimal ED pain control

involves the combined administration of NSAIDs and opioids (balanced analgesia).

22. Who requires hospitalization? Urology consultation?

Patients with high-grade obstruction, intractable pain or vomiting, associated urinary tract

infection, a solitary or transplanted kidney, and in whom the diagnosis is uncertain. Obtain

urologic consultation for patients with stones larger than 5 mm in diameter, urinary

extravasation, and renal insufficiency regardless of symptoms.

23. What advice should I give to patients being discharged from the ED?

Patients should be advised to drink plenty of fluids, strain their urine, and return to the ED if

they develop symptoms of infection or recurrent severe pain. Follow-up with a urologist within

a week should be recommended.

24. Which analgesics are recommended for outpatient pain control?

Gastrointestinal irritation limits the usefulness of oral NSAIDs in patients with renal colic;

however, rectal NSAIDs (diclofenac, indomethacin) may provide adequate analgesia. If

necessary, oral opioids can be combined with NSAIDs in patients with documented ureteral

calculi.

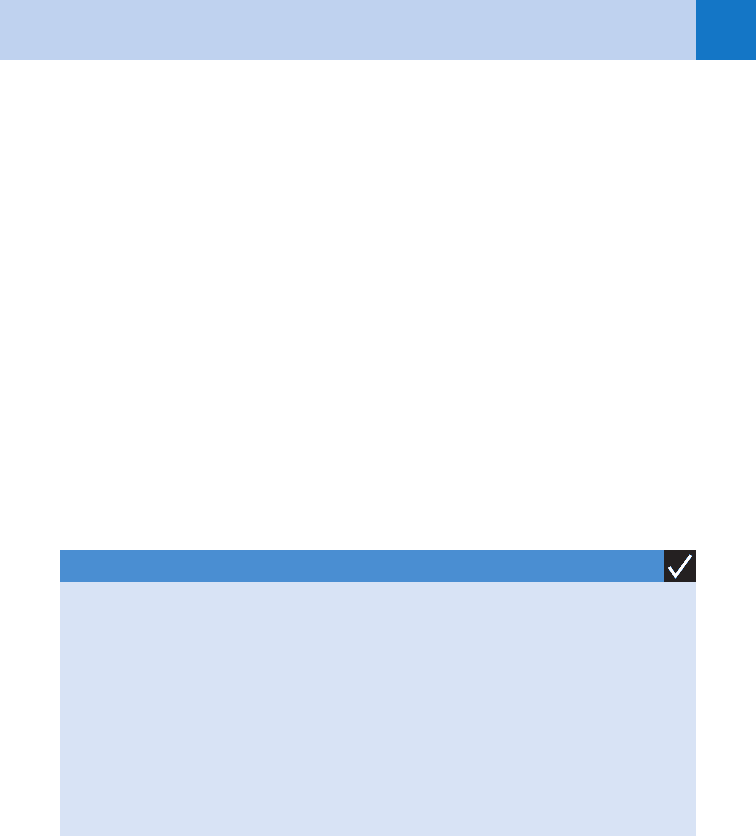

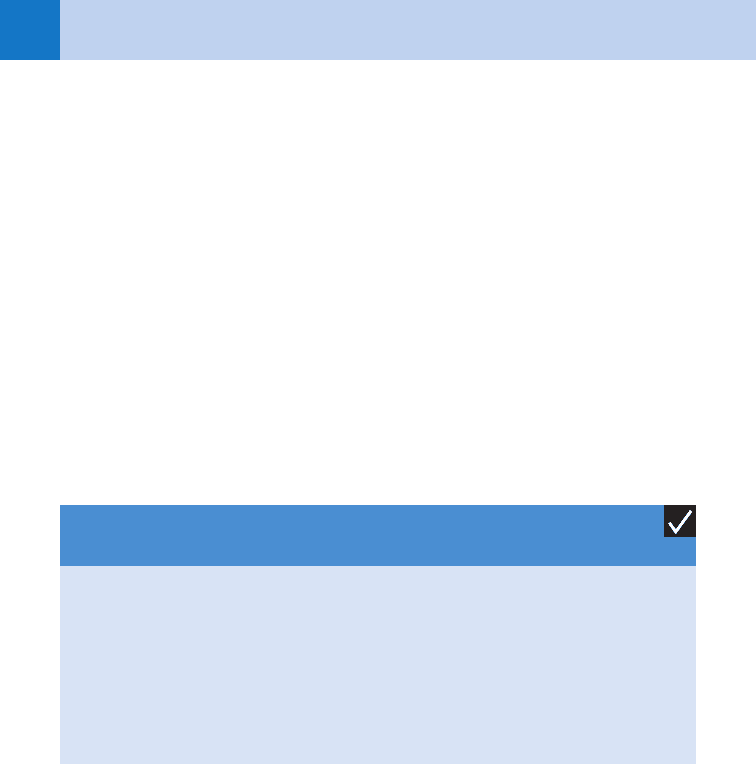

KEY POINTS: INDICATIONS FOR HOSPITALIZATION

1. Patients with high-grade obstruction

2. Intractable pain or vomiting

3. Associated urinary tract infection

4. Solitary or transplanted kidney

5. Patients in whom the diagnosis is uncertain

6. Stones larger than 5 mm in diameter

7. Urinary extravasation

8. Renal insufficiency regardless of symptoms

25. Why should patients be given a urine strainer on discharge?

If the stone can be analyzed, the patient can then receive follow-up counseling on dietary

modification or medications that may reduce the risk of recurrence.

26. When should patients return to the ED?

Patients should be instructed to seek medical care immediately if they have continued or

increasing pain, nausea and vomiting, fever or chills, or any other new symptoms.

27. What medical alternatives to active stone removal are available?

In patients with ureteral stones ,10 mm and whose symptoms are controlled with

medications, observation with periodic evaluation is an option. For such patients, appropriate

medical therapy can be offered. In such patients, calcium channel blocker or a-blocker

therapy can be used. With some data suggesting faster passage with tamsulosin, treatment

can be initiated for four weeks.

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN260

28. What is the differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with an acutely

painful scrotum?

The differential diagnosis of acute scrotal pain includes testicular torsion, torsion of the

testicular or epididymal appendages, epididymitis, orchitis, scrotal hernia, testicular tumor,

renal colic, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and Fournier’s gangrene. Although not life-threatening,

testicular torsion is a significant cause of morbidity and sterility in the male. Thus, any case of

an acute scrotum should be considered testicular torsion until proven otherwise.

29. What is testicular torsion?

Testicular torsion results from maldevelopment of the normal fixation that occurs between the

enveloping tunica vaginalis and the posterior scrotal wall. This maldevelopment then allows

the testis and the epididymis to hang freely in the scrotum (the so-called bell-clapper

deformity), allowing the testis to rotate on the spermatic cord. The degree of testicular

ischemia is dependent on the number of rotations of the cord.

30. When is testicular torsion most likely to occur?

The annual incidence of testicular torsion is estimated to be 1 in 400 for males younger than

the age of 25. Testicular torsion has a bimodal distribution, with peak incidence in the neonate

within the first few days of life and in preadolescence.

KEY POINTS: SIX DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES OF ACUTE

SCROTUM

1. Testicular torsion

2. Torsion of the testicular or epididymal appendages

3. Epididymo-orchitis

4. Scrotal hernia

5. Testicular tumor

6. Fournier’s gangrene

31. What history is suggestive of testicular torsion?

Usually, there is a history of trauma or strenuous event before the onset of scrotal pain in

testicular torsion. One study reported sudden onset of scrotal pain to be present in 90% of

patients with testicular torsion, compared with 58% of patients with epididymitis and 78% of

patients with normal scrotum. Fever was present in 10% of patients with testicular torsion

compared with 32% of patients with epididymitis.

32. What clinical features are suggestive of testicular torsion?

In testicular torsion, the affected testis usually is firm, tender, and aligned in a horizontal

rather than a vertical axis. The presence of the cremasteric reflex appears to be one of the

most helpful signs in ruling out testicular torsion with 96% negative predictive value. It is

elicited by gently stroking the inner aspect of the involved thigh and observing more than

0.5 cm of elevation in the affected testis.

33. What is the proper management of testicular torsion?

The proper management of a suspected testicular torsion is immediate urologic consultation

and surgical exploration. If surgical consultation is not immediately available, manual

detorsion should be attempted.

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN 261

34. How is manual detorsion performed?

This procedure is best done by standing at the foot or right side of the patient’s bed. The

torsed testis is detorsed in fashion similar to opening a book. The patient’s right testis is

rotated counterclockwise, and the left testis is rotated clockwise. A testis viability rate of

100%, 70%, and 20% for 6, 6–12, and 12–24 hours of symptoms, respectively, has been

reported.

35. Is imaging testing helpful to confirm the diagnosis of testicular torsion?

Testicular torsion is mainly a clinical diagnosis. If it is suspected, immediate urologic

evaluation is mandatory and should precede any further testing because time is critical.

However, imaging tests could be helpful adjuncts to the work-up of the acute scrotum when

the diagnosis is unclear.

36. What are the diagnostic imaging tests that can be used to evaluate the acute

scrotum?

Doppler ultrasound and radionucleotide scintigraphy are the two imaging tests that can be

used to evaluate the acute scrotum. Both measure the blood flow to the testis; Doppler

ultrasound carries a sensitivity of 86% and 97% accuracy, whereas radionucleotide

scintigraphy has 80% sensitivity and 97% specificity.

37. How is testicular torsion treated surgically?

The involved testis must be detorsed and then checked for viability. If it is viable, it is fixed

(orchiopexy). Because approximately 40% of patients have a bell-clapper deformity of the

contralateral testis, the unaffected testis should be fixed to prevent recurrence.

38. What are testis and epididymal appendix?

The appendix testis is a Müllerian duct remnant that is attached to the superior pole of the

testicle and rests in the groove between the testis and epididymis. The appendix epididymis is

a Wolffian duct remnant that is attached to the head of the epididymis.

39. What are clinical features of torsion of testis and epididymal appendix?

Both torsion of testis and epididymal appendix result in unilateral pain. The pain of

epididymal appendix torsion typically is more gradual in onset and is usually not quite as

severe as that associated with true testicular torsion. The most important aspect of the

physical examination is pain and tenderness localized to the involved appendix. However, late

in its course, generalized scrotal swelling and tenderness may be encountered, making it

difficult to differentiate from testicular torsion. The classic blue dot sign (visualization of the

ischemic or necrotic appendix testis through the scrotal wall on the superior aspect of the

testicle) is pathognomonic for appendix testis torsion, but it is also relatively uncommon.

40. How is torsion of testis or epididymal appendix treated?

Torsion of epididymal and testicular appendix are self-resolving, benign processes. Rest,

scrotal elevation, and analgesia are the mainstays of treatment. Resolution of the swelling and

pain should be expected within 1 week.

41. What is epididymitis?

Epididymitis arises from swelling and pain of the epididymis. It usually occurs secondary to

infection or inflammation from the urethra or bladder. Patients with epididymitis present with

KEY POINTS: PROPER MANAGEMENT OF TESTICULAR TORSION

1. Emergent urologic consultation

2. Attempt at manual detorsion

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN262

increasing, dull, unilateral scrotal pain during a period of hours to days. Possible associated

symptoms include fever, urethral discharge, hydrocele, erythema of the scrotum, and palpable

swelling of the epididymis. Involvement of the ipsilateral testis is common, producing

epididymitis-orchitis.

42. List the most common causes of epididymitis.

The most common causes of epididymitis in males older than 35 years are gram-negative

organisms such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas species. Among sexually

active men younger than 35 years, epididymitis is often caused by Chlamydia trachomatis or

Neisseria gonorrhoeae. E. coli infection also may occur in men who are insertive partners

during anal intercourse.

43. What is the treatment for epididymitis?

Admission should be considered for any febrile, toxic-appearing patient with epididymitis or

when testicular or epididymal abscess should be excluded. In-patient therapy includes bed

rest, analgesia, scrotal elevation (performed by taping a towel under the scrotum and over the

proximal anterior thighs in the supine position), NSAIDs, and parenteral antibiotics based on

presumed etiology.

When sexually transmitted disease is suspected to be the cause of epididymitis, or in males

younger than 35 years, urethral culture should be taken for Chlamydia and gonorrhea, followed

by empirical treatment with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly once, plus doxycycline 100 mg

orally twice a day for 10 days or ofloxacin 300 mg orally twice a day for 10 days. When gram-

negative bacilli are suspected to be the cause for epididymitis, or in males older than

35 years, treatment includes ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice a day or levofloxacin 750 mg

once a day for 10 to 14 days.

Treatment in all patients should also include bed rest, analgesia, and scrotal elevation.

Follow up with a urologist within 5 to 7 days is recommended.

44. What is Fournier’s gangrene?

Fournier’s gangrene, a surgical emergency, is a life-threatening disease characterized by

necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal and genital region. It is generally the result of a

polymicrobial infection from bacteria that are normally present in the perianal area. The

diagnosis and treatment of Fournier’s gangrene are similar to those of necrotizing fasciitis.

Diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, and local trauma are known risk factors. Empirical broad-

spectrum antibiotics with early aggressive surgical debridement are the mainstays of therapy.

Reexploration is commonly needed, and some patients require diverting colostomies or

orchiectomies.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Dorga V, Bhatt S: Acute painful scrotum. Radiol Clin North Am 42:49–63, 2004.

2. Eray O: The efficacy of urinalysis, plain films, and spiral CT in ED patients with suspected renal colic. Am J

Emerg Med 21:152–154, 2003.

3. Holdgate A, Pollock T: Systematic review of the relative efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and

opioids in the treatment of acute renal colic. BMJ 328:1401–1406, 2004.

4. McCollough M, Sharieff G: Abdominal surgical emergencies in infants and young children. Emerg Med Clin

North Am 21:909–935, 2003.

5. Noble VE: Renal ultrasound. Emerg Med Clin North Am 22:641–659, 2004.

6. Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, et al: 2007. guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol

2007; 178:2418.

7. Schneider R: Male genital problems. In Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, editors: Emergency medicine:

a comprehensive study guide, ed 6, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill, pp 613–620.

8. Teichman, JMH: Acute renal colic from ureteral calculus. N Engl J Med 350:684–693, 2004.

Chapter 36 RENAL COLIC AND SCROTAL PAIN 263

9. Van Glabeke E, Khairouni A, Larroquet M, et al: Acute scrotal pain in children: results of 543 surgical

explorations. Pediatr Surg Int 15:353–357, 1999.

10. Workowski KA, Berman SM: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep

55:1, 2006.

11. Worster A, Preyra I, Weaver B, et al: The accuracy of noncontrast helical computed tomography versus

intravenous pyelography in the diagnosis of suspected acute urolithiasis: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med

40:280–286, 2002.

264

ACUTE URINARY RETENTION

CHAPTER 37

John P. Marshall, MD

1. What is acute urinary retention (AUR)?

A painful inability to urinate. AUR is most commonly the result of bladder outlet

obstruction, but it also may result from neurogenic, pharmacologic, or other causes of

detrusor muscle dysfunction. Urine is produced normally but is retained in the bladder,

which then becomes distended and uncomfortable.

2. Is there chronic urinary retention?

Yes. It generally represents prolonged retention. The hallmarks of chronic urinary

retention are (a) the absence of pain and (b) overflow incontinence. It most frequently

occurs in mentally debilitated or neurologically compromised patients.

3. What is the most common cause of AUR? Who gets it?

Obstruction of the lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra) is the most common

cause encountered in the ED. In general, AUR is a disease of older men, although it is

occasionally encountered in women. The usual site of obstruction is the prostate gland,

but lesions of the urethra or penis also may cause retention. Patients with indwelling

catheters (suprapubic or Foley) are at risk for episodes of retention because of

obstruction or dysfunction of these drainage systems.

4. How does benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) cause AUR?

BPH with bladder neck obstruction is the most common cause of AUR. Of men older

than age 60, 50% have histologic evidence of BPH. As the prostate hypertrophies, urine

outflow is obstructed by enlargement of the median lobe of the gland impinging on the

internal urethral lumen. The typical patient with BPH gives a progressive history

suggestive of urinary outlet obstruction. Symptoms such as hesitancy, diminished

stream quality, dribbling, nocturia, and the sensation of incomplete bladder emptying

may precede the episode of acute retention. New medications or increased fluid loads

may precipitate an acute episode of retention in these patients.

5. List the other causes of AUR.

n

Obstructive: BPH, prostate carcinoma, prostatitis, urethral stricture, posterior urethral

valves, phimosis, paraphimosis, balanitis, meatal stenosis, calculi, blood clots,

circumcision, urethral foreign body, constricting penile ring, and clogged or crimped

Foley catheter

n

Neurogenic: Spinal cord injuries, herniated lumbosacral disks (cauda equina

syndrome), central nervous system (CNS) tumors, stroke, diabetes, multiple

sclerosis, encephalitis, tabes dorsalis, syringomyelia, herpes simplex, herpes zoster,

and alcohol withdrawal

n

Pharmacologic: Anticholinergics, antihistamines, antidepressants, antispasmodics,

narcotics, sympathomimetics, antipsychotics, and antiparkinsonian agents (see

Question 14)

n

Psychogenic: Diagnosis of exclusion

Chapter 37 ACUTE URINARY RETENTION 265

6. What are the important features in the history and physical examination?

When taking the history, any previous prostate or urethral conditions should be elicited.

Patients often have a history of chronic voiding hesitancy, a decreased force to the urinary

stream, a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, or nocturia. Information about neurologic

symptoms, trauma, previous instrumentation, back pain, and current medication is essential.

On physical examination, the distended bladder often is palpable above the pubic rim and

indicates at least 150 mL of urine in the bladder. The penis or vulva, and particularly the

urethra should be examined carefully for any signs of stricture, which may be evident on

palpation. A rectal examination is essential and often provides clues to the diagnosis of BPH,

prostate carcinoma, or prostatitis. A careful neurologic examination, including rectal tone and

perineal sensation, is vital in any patient suspected of having a neurologic lesion.

7. Are there any red flags in the history and physical examination that might

indicate a more serious, potentially surgical, cause?

Yes. New urinary symptoms, particularly obstruction, in patients with a history of trauma or

back pain should alert the examiner to the possibility of spinal cord compression resulting

from disk herniation, fracture, epidural hematoma, epidural abscess, or tumor. Be especially

suspicious if there is no prior history of bladder, prostate, or urethral disorders.

8. How do I treat AUR?

Catheterization and bladder decompression using a Foley catheter.

9. What if I can’t pass a Foley catheter?

Occasionally, simple passage of a 16- or 18-French Foley catheter cannot be accomplished. One

trick that often helps is to fill a 30-mL syringe with lidocaine (Xylocaine) jelly and inject it into the

urethral meatus. Still no luck? Try an 18- or 20-French coudé catheter. The coudé-tipped catheter

has a gentle upward curve in the distal 3 cm that may be helpful in pointing the catheter up and

over the enlarged prostatic lobe. Never force a catheter through an area of significant resistance

because this can cause urethral perforation, false lumens, and subsequent stricture formation.

10. Is bigger better?

A loaded question. If you are unable to pass a 16-French (standard adult) catheter, it is generally

recommended to move up in size to an 18- or 20-French Foley catheter. Usually, the stiffness and

larger bulk of the bigger catheter are more successful in passing through the bladder neck than a

smaller, more flexible catheter. Remember, never force a catheter through significant resistance.

11. What if nothing is working?

If you still cannot pass a catheter, the obstruction may be more severe than anticipated, or a

stricture may be present. One clue to the presence of a stricture in adult males is that the

obstruction occurs less than 16 cm from the external meatus of the urethra. If this is the case,

an attempt may be made using a pediatric-sized urinary catheter. If this fails, more

sophisticated instrumentation may be required, such as filiforms and followers or catheter

guides. These techniques should be done only by a urologist or practitioner with extensive

training in their use. If AUR cannot be relieved by transurethral bladder catheterization,

placement of a suprapubic catheter may be necessary.

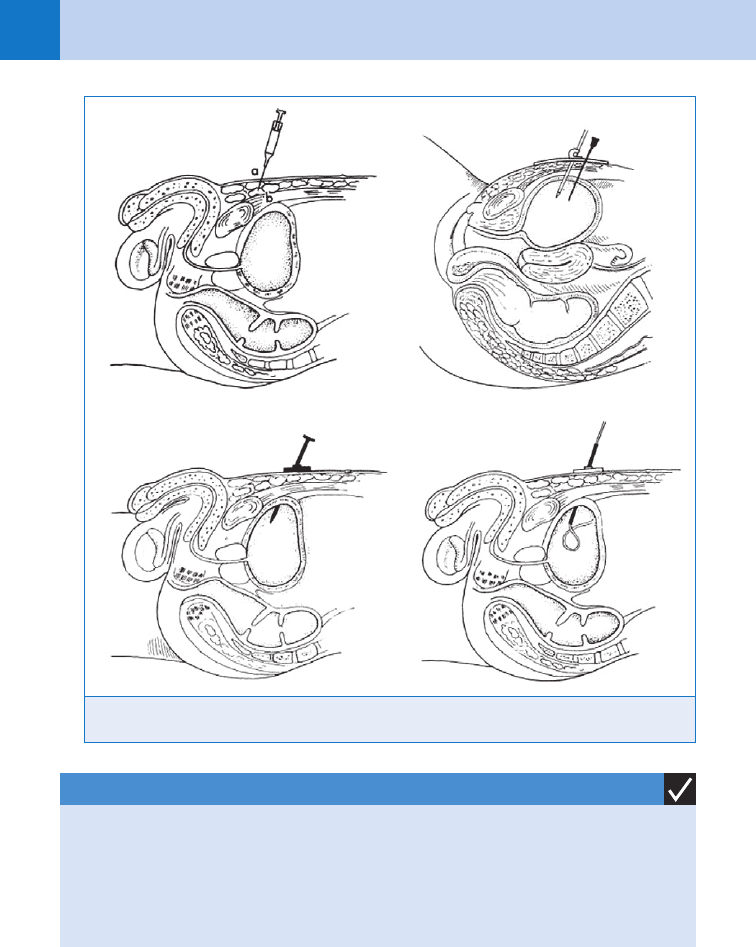

12. What is suprapubic catheterization? How is it done?

A procedure used to pass a urinary catheter directly into the bladder through the lower anterior

abdominal wall (see Fig. 37-1). It is indicated when bladder drainage is necessary and other

methods have failed or when urethral damage from trauma is suspected. The procedure is done

under sterile conditions with local anesthesia. The presence of a distended bladder is confirmed

by ultrasound or percussion. A small midline incision is made 2 cm above the symphysis pubis.

Depending on the technique, either a needle or a trocar is used to penetrate the bladder through

the incision. When urine is aspirated, a catheter is advanced over the cannula.

Chapter 37 ACUTE URINARY RETENTION266

KEY POINTS: TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR AUR

1. Foley catheter placement

2. Coudé catheter placement

3. Filiforms and followers

4. Suprapubic catheterization

13. What diagnostic studies are useful in the evaluation of AUR?

Bedside ultrasonography can be helpful during the initial evaluation, and, if needed, can

facilitate suprapubic aspiration. Always check a urinalysis with microscopic examination and

urine culture. It is generally recommended to check blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels

to evaluate renal function, especially in cases of suspected chronic retention.

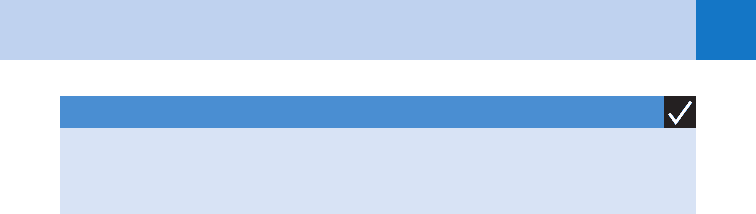

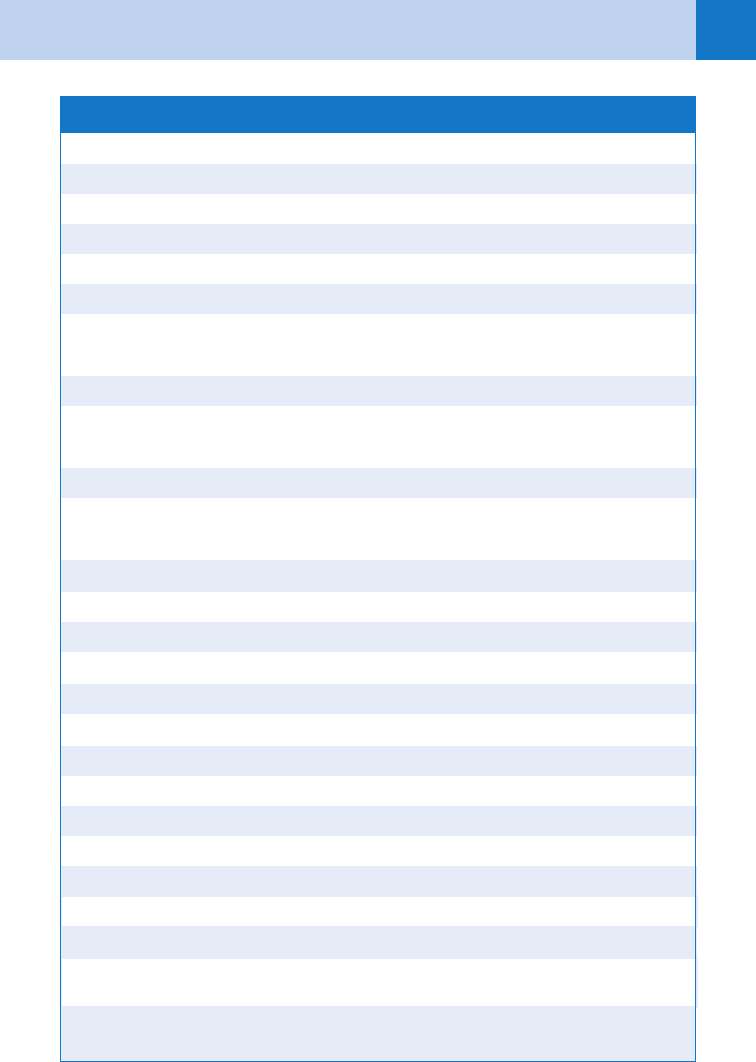

14. Which medications may cause AUR?

Table 37-1 presents the broad categories, as well as some specific medications that can

cause AUR.

Figure 37-1. Suprapubic catheterization. (From Roberts J, Hedges J: Clinical procedures in emergency

medicine, Philadelphia, 2000, W. B. Saunders.)

A B

C D

Chapter 37 ACUTE URINARY RETENTION 267

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Sympathomimetics (Alpha-Adrenergic) Antipsychotics

Ephedrine Haloperidol

Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, Actifed) Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

Phenylephrine hydrochloride (Neo-Synephrine) Prochlorperazine (Compazine)

Phenylpropanolamine hydrochloride (Contac) Risperidone (Risperdal)

Amphetamine Clozapine (Clozaril)

Cocaine Quetiapine (Seroquel)

Sympathomimetics (Beta-Adrenergic) Antihypertensives

Isoproterenol Nifedipine (Procardia)

Terbutaline Hydralazine

Antidepressants Nicardipine

Tricyclic Muscle Relaxants

Fluoxetine (Prozac) Diazepam (Valium)

Antidysrhythmics Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril)

Quinidine Narcotics

Disopyramide (Norpace) Morphine sulfate

Procainamide Codeine

Anticholinergics Meperidine (Demerol)

Antihistamines Hydromorphone hydrochloride (Dilaudid)

Antiparkinsonian Agents Miscellaneous

Benztropine (Cogentin) Indomethacin

Amantadine (Symmetrel) Metoclopramide (Reglan)

Levodopa (Sinemet) Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

Trihexyphenidyl (Artane) Mercurial diuretics

Hormonal Agents Dopamine

Progesterone Vincristine

Estrogen MDMA

Testosterone Cannabis

TABLE 37–1. MEDICATIONS THAT CAN CAUSE ACUTE URINARY RETENTION