Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 47 SEPSIS SYNDROMES328

6. What is the mortality rate of sepsis versus severe sepsis?

The mortality rate of sepsis is 15% to 20%, whereas severe sepsis has a 30% to 40%

mortality rate.

7. What is the primary goal of resuscitation in a septic patient?

Aggressive resuscitation aims to ensure that oxygen delivery meets oxygen demand of tissues

affected by the septic state.

8. What is an easy way to decrease an affected tissue’s increased oxygen

demand from sepsis?

Early appropriate antibiotics. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement recommends initiation

of antibiotics within 3 hours of ED presentation.

9. What are two means of increasing oxygen supply to affected tissues in a

septic state?

n

High-flow supplemental oxygen

n

Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT)

10. What is the mortality benefit to initiating EGDT in severe sepsis patients?

There is a 10% to 20% reduction in mortality.

11. What are the goals outlined in EGDT for patients in severe sepsis?

During the first 6 hours of resuscitation, the goals for initial resuscitation of sepsis-induced

hypoperfusion should include all of the following as part of a treatment protocol:

n

Central venous pressure (CVP): Goal of 8 to 12 mm H

2

O

n

Mean arterial pressure (MAP): Goal of . 65 mm Hg

n

Urine output: Goal of > 0.5 mL/kg/h

n

Central venous (ScVO

2

obtained from the pulmonary artery) or mixed venous oxygen

saturation (SvO

2

) obtained from the superior vena cava: Goal of .70%

12. What intervention should be used for a CVP that is less than 8 mm H

2

O?

Intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation is the first-line treatment and is given in bolus increments

over 30 minutes or until CVP is at the desired goal. Use boluses of 500 to 1000 mL of

crystalloids or 300 to 500 mL of colloids, repeated based on response. Caution needs to be

used in patients with contraindications to significant volume resuscitation (e.g., patients with

congestive heart failure [CHF] or renal failure).

13. What intervention should be initiated for a MAP that is less than 65 mm Hg?

After adequate attempts to raise the patient’s CVP to between 8 and 12 mmH

2

O with fluid

resuscitation (at least 20–40 mL/kg), initiate vasopressor support to increase MAP to

65 mm Hg.

14. Does one vasopressor have a proven benefit over another in the setting of

severe sepsis?

Some evidence suggests that norepinephrine is a better first-line vasopressor than dopamine

in the setting of sepsis. Although the jury may still be out on that point, it is agreed that both

dopamine and norepinephrine are good first- and second-line agents for supportive care in

sepsis. Epinephrine is associated with higher mortality in animal models and is generally

reserved for use if the patient is failing both dopamine and norepinephrine.

15. What are the implications of a low SvO

2

?

This simply means there is a global tissue hypoxia. An SvO

2

of less than 70% suggests that

the tissue extraction of O

2

is greater than the delivery needed to sustain the metabolic

demands (i.e., poor perfusion).

Chapter 47 SEPSIS SYNDROMES 329

16. What intervention should be initiated for an SvO

2

,70%?

n

If the SvO

2

is less than 70% despite a CVP of at least 8 to 12 mmH

2

O and a MAP of at least

65 mm Hg, then consider the use of dobutamine for its inotropic properties to help with

cardiac pump function, perfusion, and O

2

delivery.

n

Additionally, one may consider transfusing packed red blood cells to increase the patient’s

hematocrit to a level of 30%. This will help increase oxygen-carrying capacity.

17. What are the drawbacks to transfusion?

Transfusion of blood is initially helpful. There are, however, several potential drawbacks. Acute

transfusion reactions and systemic response to minor antigens and storage breakdown

products may further increase the immunocompromised state associated with sepsis.

Additionally, the optimal end point of transfusion is unclear.

18. Is SvO

2

a reasonable surrogate measure to central venous oxygen

saturation (ScVO

2

)?

Recommendations from the latest international sepsis forum suggest that SvO

2

from a central

line placed in the superior vena cava is a comparable and reliably accurate estimate of the

ScVO

2

gained from a pulmonary artery catheter, Swan-Ganz catheter.

19. What are the implications of meeting these goals as quickly as possible?

There is a clear benefit from aggressively clearing lactate and reversing tissue hypoperfusion

in severe sepsis using the goals of EGDT. Rivers and colleagues demonstrated a 16%

decrease in absolute 28-day mortality by implementing EGDT through the first 6 hours of

patient presentation to the ED.

20. How is septic shock defined?

Septic shock can be defined as severe sepsis with ongoing tissue hypoperfusion refractory to

resuscitation.

21. What is the role of vasopressin?

Currently, vasopressin is a second- to third-line vasopressor and is reserved for failure of

other vasopressors in the setting of septic shock with refractory hypotension. Vasopressin

does not confer a mortality benefit and causes extreme peripheral vasoconstriction that may

result in digital ischemia.

22. What is the role of recombinant activated protein C (rhAPC) in sepsis?

Recombinant APC (Drotrecogin Alfa) is a novel sepsis therapy that has demonstrated a 6.1%

to 13% absolute reduction in mortality in some studies. The mortality benefit appears to be

highest in those who are the sickest with an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

(APACHE II) score .25. The use of rhAPC in all septic patients is controversial due to the lack

of efficacy in studies of patients with APACHE II scores ,25 and the expense of the treatment.

The cost of each treatment is currently around $8,000.

23. What is the role of tight glycemic control in sepsis?

There are data to demonstrate that in critically ill patients there is a 50% reduction from 8%

to 4.6% in intensive care unit (ICU) mortality with tightly controlled glucose between 80 and

110 mg/dL. Therefore, it is recommended that an aggressive insulin-controlled glucose

protocol be started in critically ill patients in the ED.

WEBSITE

Institute for Healthcare Improvement: www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/Sepsis/

Chapter 47 SEPSIS SYNDROMES330

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masun H, et al: Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines for management of severe

sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 32:858–873, 2004.

2. Rivers EP, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis. N Engl J

Med 340:207–214, 1999.

3. Shapiro NI, Howell M, Talmor D, et al: A blueprint for a sepsis protocol. Acad Emerg Med 12:352–329, 2005.

4. Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S: Bacteremia, sepsis, and septic shock. In Wolfson AB, editor: Harwood-Nuss’ clinical

practice of emergency medicine, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp 706–711.

331

SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS

CHAPTER 48

Harvey W. Meislin, MD, FACEP, FAAEM and Megan A. Meislin, MD

1. How do I differentiate cellulitis from an abscess?

Cellulitis is a soft-tissue infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue usually characterized by

blanching erythema, swelling, pain or tenderness, and local warmth. A cutaneous abscess is a

localized collection of pus that results in a painful soft-tissue mass that is often fluctuant but

surrounded by firm indurated granulation tissue and erythema.

2. What are the causes of cellulitis? How does it progress?

Although most often acute, cellulitis may be subacute or chronic. Cellulitis occurs most often

in the lower extremities, then the upper extremities, followed by the face. Minor trauma is

often the predisposing cause, but hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination may account

for its appearance in previously normal skin. Bacterial cellulitis may progress to ascending

lymphangitis and septicemia. Cellulitis caused by bacterial infection tends to spread radially

with associated swelling, whereas nonbacterial or inflammatory cellulitis tends to stay

localized.

3. What are the causes of abscesses? How do they progress?

Abscesses occur on all areas of the body, although they have a predominance for the

axilla, perirectal region, head and neck, and extremities, respectively. The cause of

localized abscesses depends on the anatomic region involved; abscesses on the

extremities are usually caused by interruptions of the integrity of the protective epithelium;

head and neck abscesses tend to be associated with obstruction of the apocrine glands;

oral and perineal abscesses originate from the mucous membranes. Superficial abscesses

tend to remain localized and often rupture spontaneously through the skin if not incised

and drained.

KEY POINTS: CELLULITIS VERSUS ABSCESS

1. Abscesses contain pus; cellulitis does not.

2. Fluctuance surrounded by induration signifies fluid, usually pus. Fluctuance, if present,

signifies abscess formation; the absence of fluctuance does not rule out an abscess.

3. There is an increasing incidence of community-associated MRSA.

4. Community-associated MRSA has different sensitivities and susceptibilities to antibiotics

than does hospital-associated MRSA.

5. Treatment for cellulitis is immobilization, elevation, heat, analgesics, and antibiotics.

6. Cutaneous abscesses can, in general, be treated solely with incision and drainage.

4. What is pus? Why is the presence of pus significant?

Pus is a heterogeneous mix of cellular material in various stages of digestion by

polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). These PMNs are drawn to sites of inflammation,

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS332

infection, or trauma by various chemotactic factors to defend the host against potential

pathogens. Abscesses contain pus, whereas cellulitis does not. Thus abscess and cellulitis

may be present in the same anatomic area; the presence of pus defines the diagnosis of an

abscess and the need for incision and drainage.

5. How do I know if pus is present?

In cutaneous abscesses, a raised painful mass with a fluctuant center surrounded by indurated

erythematous tissue signifies the presence of pus. Adjunctive radiographic techniques, such

as ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan, may be useful for deeper soft-tissue

infections but are rarely indicated with cutaneous abscesses. The use of a localizer needle is

often helpful, especially in wounds in which the purulence is loculated. Needle aspiration of

the involved area with a needle large enough to withdraw thick pus often helps to define the

location of purulence for incision and drainage and makes the process more comfortable by

decreasing the pressure and pain in the area.

6. What are the differential diagnoses for cellulitis and abscess?

The differential for cellulitis and abscess is one of bacterial versus nonbacterial infection.

The etiologies of nonbacterial cellulitis include arthropod envenomation, chemical or

thermal burns, arthritis, and healing wounds. Nonbacterial cellulitis is usually localized and

often lacks lymphangitic streaking. The differential diagnosis of abscesses includes sterile

abscesses, cutaneously borne bacterial abscesses, and mucous membrane abscesses.

Abscesses of the oral and anorectal area usually originate from flora indigenous to those

areas. Sterile abscesses, which occur approximately 5% of the time, tend to be associated

with drug abuse and subcutaneous injections. Most abscesses are isolated; recurrent

abscess formation signifies a more complicated or systemic disease process.

7. Is it useful to culture cellulitis or abscesses?

Culturing cellulitis is often futile because a causative agent is identified only 10% of the time.

Often there is secondary skin contamination leading to misidentification of the cause. Cultures

can be useful, however, in patients who do not respond to initial management, in patients with

recurrent disease, or in patients with sepsis. Culturing the portal of entry may be useful, even

if distal to the site of the cellulitis. Culturing of cutaneous abscesses seldom is clinically

indicated in patients with normal host defenses because they tend to contain and localize the

process. In patients with AIDS, diabetes mellitus, leukemia, vascular insufficiency, trauma,

burns, or recurrent abscess, or when concerned for community-associated methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or with failure of initial therapy, Gram stain and

culture may be indicated.

8. What is the yield of blood cultures when treating cellulitis?

A number of studies have demonstrated that the routine ordering of blood cultures in the ED

is not warranted in an immunocompetent host with uncomplicated cellulitis, except in

suspected cases of Haemophilus influenzae, type B. The impact on clinical management is

marginal. One study reported that blood cultures were twice as likely to be contaminated as to

be true positives. Blood cultures should be considered prior to starting antibiotic therapy in

immunocompromised patients, in those with an exposure to unusual organisms, and in

patients with a potentially complicated cellulitis.

9. What is community-associated MRSA?

MRSA was first recognized as a community-associated pathogen in the early 1980s.

Community-associated MRSA skin and soft-tissue infections are spread within the community

and are genetically distinct from hospital-associated MRSA infections. Community-associated

MRSA has different sensitivities and susceptibilities to antibiotics than hospital-associated

MRSA as well.

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS 333

10. Who is at risk for acquiring community-associated MRSA?

The prevalence of MRSA colonization in the community ranges from 0.2% to 2.8%. Highest

rates are seen among poor urban populations. There is a high prevalence among injection

drug users, as well as in prison populations, athletes sharing equipment, and isolated

American Indian communities.

11. Is there a role for routine laboratory studies?

Laboratory studies are generally not helpful in the treatment of superficial soft-tissue

infections, unless signs or symptoms of systemic illness are present or the patient is

immunocompromised. These patients are often not systemically ill, and even an elevated white

blood cell (WBC) count does not differentiate bacterial from nonbacterial infection, identify the

presence of abscess or cellulitis, or show systemic involvement. An exception may be

H. influenzae cellulitis, in which WBC counts often exceed 15,000/mm

3

with a left shift, often

occurring in children.

12. Summarize appropriate treatment of soft-tissue infections.

The time-honored treatment for cellulitis is immobilization, elevation, heat or warm moist

packs, analgesics, and antibiotics directed toward suspected pathogens. The treatment for

cutaneous abscesses is a properly performed incision and drainage.

13. Should I routinely prescribe antibiotics for patients with an abscess?

No. The treatment for most cutaneous abscesses is incision and drainage, and neither

antibiotics nor cultures are indicated in patients with normal host defenses as long as the

abscess is localized. In patients with complications of diabetes, AIDS, leukemia,

neoplasms, significant vascular insufficiency, trauma, thermal burns, or suspicion for

MRSA, antibiotics should be considered as prophylaxis to prevent spread of bacteria into

local tissues or the bloodstream. Prophylactic antibiotics, although usually not necessary,

may also be considered for abscesses of the face, groin, and hand. For abscesses

associated with immunocompromised patients, progressing cellulitis, hospital-acquired

MRSA, and penetration into deeper soft tissues, incision and drainage (often in the

operating room), antibiotic therapy, culture, and Gram stain constitute a reasonable initial

approach.

The selection of antimicrobial agent can be facilitated by knowing the flora associated with

the anatomic area involved, if the abscess is from a cutaneous or mucosal process, and the

most likely cause of the infection. Gram stain results of the purulence in these cases may be

helpful.

14. How do you treat community-associated MRSA?

Often simple abscesses can be treated solely with incision and drainage, but when

antibiotics are deemed appropriate in the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections, it is

no longer recommended to use a b-lactam such as cephalexin. Antimicrobial susceptibility

patterns of MRSA all demonstrate uniform resistance to oxacillin. Susceptibilities appear

highest to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, tetracycline, levofloxacin, and

vancomycin.

15. How does the presence of community-associated MRSA change the

management of soft-tissue infections in the ED?

Previously, it was recommended that all suspected MRSA abscesses should be cultured in the

ED prior to starting antimicrobial therapy. Antibiotics active against community-associated

MRSA should be used in the treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections determined to require

antimicrobial treatment. However, it does appear that localized cutaneous abscesses with

community-acquired MRSA will respond to incision and drainage alone without the need for

adjunctive antibiotics.

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS334

16. Are there anatomic areas of significance in a patient with an abscess or

cellulitis?

Cellulitis of the midface, especially in the area of the orbits, must be treated aggressively. The

venous drainage of these infections is through the cavernous sinus of the brain, with the

potential for causing cavernous sinus thrombosis. In true orbital cellulitis, aggressive

intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy is warranted. Often a CT scan is performed to detect

abscess formation. H. influenzae cellulitis usually occurs in children, resulting in high fevers,

high WBC counts, and bacteremia. Perirectal or perianal abscesses that are large or extend

into the supralevator or ischiorectal space often need intraoperative management, removing

not only the abscess but also the fistulae that are often associated with it. Deep space

abscesses of the groin and head and neck region also must be drained in the operating room

because of their proximity to major neurovascular structures.

17. Describe appropriate follow-up care.

Most patients with simple cellulitis and localized abscesses can be treated on an outpatient

basis. Abscess packing from an incision and drainage procedure can be removed after 48 to

72 hours, and the patient can clean the abscess cavity by bathing or showering at home. It is

important to ensure that cellulitis is responding to therapy and, in the case of abscess, that all

pus has been drained and evacuated. Further follow-up is indicated only when the processes

are recurrent, when there is no response to therapy in 48 to 72 hours, or when the patient is

immunocompromised.

18. Who should be admitted to the hospital?

Patients who appear septic, are immunocompromised, are not responding to treatment;

patients with soft-tissue infections in certain anatomic sites, such as the central area of the

face; and patients with infections, such as sublingual and retropharyngeal abscesses and

Ludwig’s angina that potentially may cause airway closure, should be admitted. Close attention

must be paid to immunosuppressed patients, who may develop abscesses or cellulitis as

secondary infections from gram-negative or anaerobic gas-forming organisms. Abscesses in

the perineal area may spread quickly through the fascial planes, resulting in Fournier’s

gangrene.

19. Is there an association between abscesses or cellulitis and systemic

disease?

Patients who are immunocompromised or have peripheral vascular disease have a tendency to

develop superficial soft-tissue infections. Recurrent abscesses in the head and neck or groin

regions may be associated with hidradenitis suppurativa, which is a disease of chronic

suppurative abscesses of the apocrine sweat glands. Inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes,

malignancies, and pregnancy have been associated with a higher incidence of perirectal

abscesses. Recurrent abscesses in the perineal and lower abdominal area may signify the

presence of associated inflammatory bowel disease. All patients with recurrent soft-tissue

infections, whether superficial or deep, should be evaluated for underlying systemic disease

such as diabetes.

20. What is the best advice overall for treating cellulitis and abscesses?

Cellulitis usually responds to antibiotic therapy and immobilization. Cutaneous abscesses

usually respond to adequate incision and drainage; antibiotics are not indicated. All soft-tissue

infections should be observed to ensure that healing is occurring. Selection of antibiotics,

when indicated, is guided by the location and cause of the infection.

21. What is necrotizing fasciitis?

A life-threatening and limb-threatening bacterial infection of the fascia often extending to the

skin and subcutaneous tissue. Multiple bacteria are usually involved. The most common are

gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus and Staphylococcus), gram-negative organisms

(Enterococcus, Proteus, and Pseudomonas), and anaerobes (Clostridium, Escherichia coli,

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS 335

Bacteroides fragilis). Bacteria usually enter the subcutaneous tissue through a break in the

skin, often caused by minor or trivial trauma. Bacterial substances or exotoxins cause

separation of the dermal connective tissue resulting in inflammation and necrosis. Blood-

borne and postoperative infection may lead to necrotizing fasciitis.

22. How is necrotizing fasciitis diagnosed?

The diagnosis should be considered in any patient with a soft-tissue infection who has pain

and tenderness out of proportion to the visible degree of cellulitis. It also should be

considered in patients without any skin changes who have exquisite tenderness without any

obvious reason such as a history of musculoskeletal trauma. Some patients may have

subcutaneous emphysema. Most patients develop sepsis late in the course, and in severe

cases disseminated intravascular coagulopathy develops. A soft-tissue radiograph may be

helpful to visualize subcutaneous emphysema. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are

helpful when this diagnosis is suspected. Later in the course, the skin may reveal bullous

lesions and necrotic patches.

KEY POINTS: NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

1. Pain and tenderness are out of proportion to the visible degree of cellulitis.

2. Subcutaneous emphysema may be present.

3. This is a disease requiring early surgical consultation.

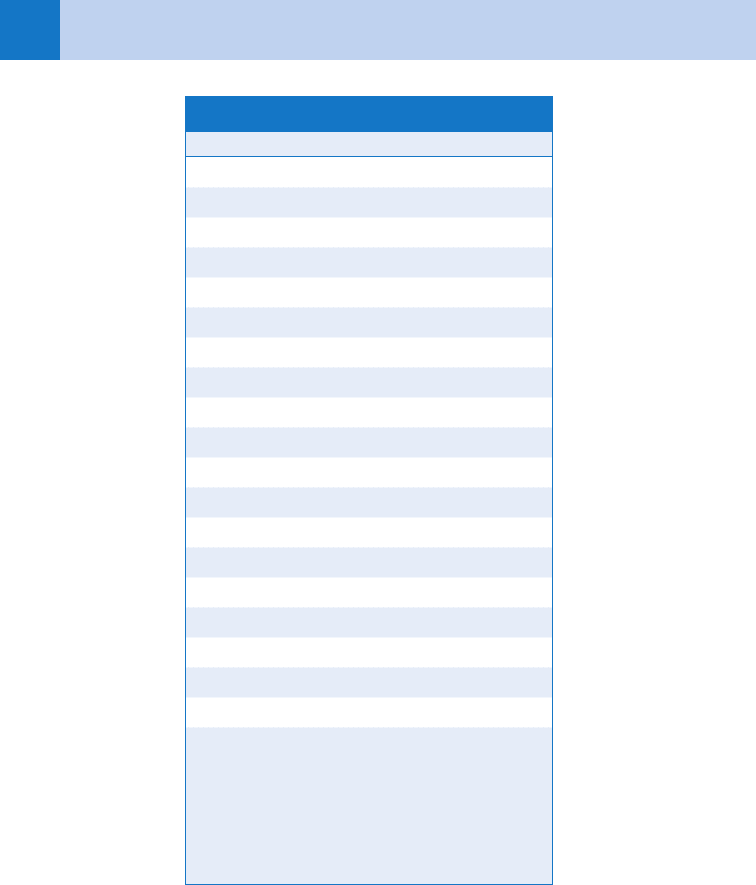

23. What is the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score?

The LRINEC score is a scoring system developed from a retrospective analysis to differentiate

between necrotizing fasciitis and other soft-tissue infections. The score is calculated by

totaling up the six predictive factors in Table 48-1. A score of 6 or greater had a positive

predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive value of 96%.

24. Why should I get a surgical consultation?

Necrotizing fasciitis is a disease that must be rapidly treated with extensive incision, drainage,

and debridement of necrotic tissue. Additional therapy includes IV antibiotics and in-hospital

supportive care.

25. What is Fournier’s gangrene?

A necrotizing subcutaneous infection of the perineum occurring primarily in men, usually

involving the penis and scrotum. It most commonly affects individuals who are

immunologically compromised or diabetic. Typically, it begins as a benign infection or small

abscess with symptoms of pain and itching that quickly progresses and leads to end-artery

thrombosis in subcutaneous tissues. Ultimately, it leads to widespread necrosis of adjacent

areas. Any patient complaining of lesions or pain in the aforementioned areas should be

approached with this diagnosis in the differential.

26. List the most common (and concerning) organisms found in the following

wounds and their accompanying cellulitis.

n

Cat bites: Pasteurella multocida (80%), Staphylococcus, Streptococcus

n

Dog bites: Pasteurella, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Capnocytophaga canimorsus (rare,

but 25% fatality in immunocompromised patients)

n

Human bites: Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, H. influenzae, Eikenella corrodens,

Enterobacter, Proteus

n

Open water wounds: Aeromonas hydrophila, Bacteroides fragilis, Chromobacterium,

Mycobacterium marinum, Vibrio

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS336

LRINEC, laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis).

To convert the values of glucose to milligrams per deciliter,

multiply by 18.015. To convert the values of creatinine to

milligrams per deciliter, multiply by 0.01131.

Variable Score

C-reactive protein (mg/L)

,150 0

150 or more 4

Total white cell count (per mm

3

)

,15 0

15–25 1

.25 2

Hemoglobin (g/dL)

.13.5 0

11–13.5 1

,11 2

Sodium (mmol/L)

135 or more 0

,135 2

Creatine (mmol/L)

141 or less 0

.41 2

Glucose (mmol/L)

10 or less 0

.10 1

TABLE 48-1. THE LRINEC SCORE

27. What question must be asked of all patients presenting with cellulitis

or abscesses?

When was your last tetanus booster? Current recommendations suggest tetanus-diphtheria

toxoid (Td), 0.5 mL IM 3 1, if it has been more than 5 years since the previous booster.

Chapter 48 SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS 337

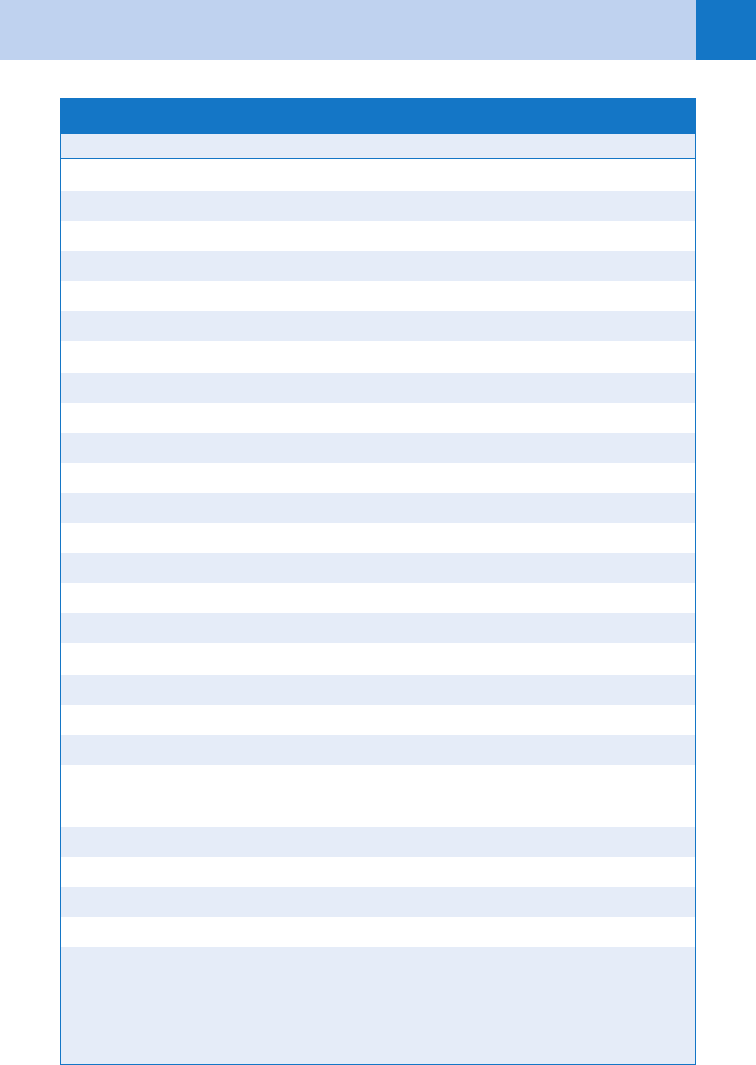

bid, twice a day; d, day; q, every; qid, four times a day; tid, three times a day; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-

sulfamethoxazole.

Drug Dose

Group A Streptococcus

Penicillin V (phenoxymethylpenicillin) 250–500 mg qid

First-generation cephalosporin 250–500 mg qid

Erythromycin 250 mg–1 g q 6 h

Azithromycin 500 mg 3 1 dose, then 250 mg q day 3 4

Clarithromycin 500 mg bid

Staphylococcus aureus (not methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus)

Dicloxacillin 125–500 mg qid

Cloxacillin 250–500 mg qid

First-generation cephalosporin 250–500 mg qid

Erythromycin (variable effectiveness) 250–500 mg qid

Azithromycin 500 mg 3 1 dose, then 250 mg q day 3 4

Clarithromycin 500 mg bid

Clindamycin 150–450 mg qid

Amoxicillin-clavulanate 250–500 mg tid

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid

S. aureus (community-associated methicillin-resistant) MRSA

Trimethoprim (TMP)-sulfamethoxazole (SMX) 160 mg TMP/800 mg SMX bid

Clindamycin 150–450 mg qid

Tetracycline 250–500 mg qid

Linezolid 600 mg bid

Haemophilus influenzae

Amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg bid

Cefaclor 250–500 mg tid

TMP-SMX 160 mg TMP/800 mg SMX bid

Azithromycin 500 mg 3 1 dose, then 250 mg q day 3 4

Clarithromycin 500 mg bid

TABLE 48-2. ORAL THERAPY FOR SUPERFICIAL SOFT-TISSUE INFECTIONS