Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 62 ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISORDERS IN CHILDREN438

Step 5. Admission criteria

n

Albuterol treatment required every 2 hours or more.

n

Continued hypoxemia by pulse oximetry.

n

Continued poor response requiring escalation of treatment.

25. What about magnesium?

The mechanism of action of IV magnesium is not known but is hypothesized to be the

counteraction of calcium ions to prevent bronchial smooth muscle contraction. The benefit in

patients with mild to moderate exacerbations is unclear, and its use should be reserved for

those patients in severe distress or nonresponsive to albuterol and steroids. Dose is 75 mg/kg

IV (maximum of 2 g).

26. Does aminophylline have any use?

Aminophylline and theophylline do not have a role in the routine management of the pediatric

asthma patient in the ED. IV aminophylline has been shown to improve lung function in

children with severe asthma exacerbations, but it does not reduce symptoms, number of

nebulizer treatments, or length of stay. Several studies have failed to show benefit of

theophylline when added to bronchodilators and steroids in noncritically ill patients. There are

inconclusive data to suggest that theophylline may be equally effective to terbutaline in

pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) patients.

27. What about parenteral b-agonists?

Use of systemic b-agonists is controversial; few well-designed studies have evaluated their use.

They should be considered in patients with severe exacerbations who have failed to respond to

maximal inhaled therapy. Terbutaline, subcutaneously or intravenously, may be given as an initial

bolus of 10 mg/kg followed by a continuous infusion starting at 0.5 mg/kg/min. Epinephrine may

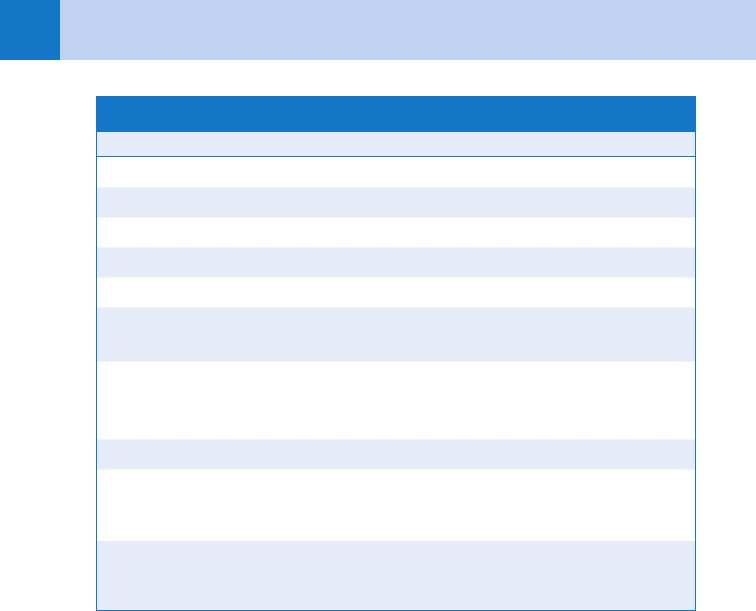

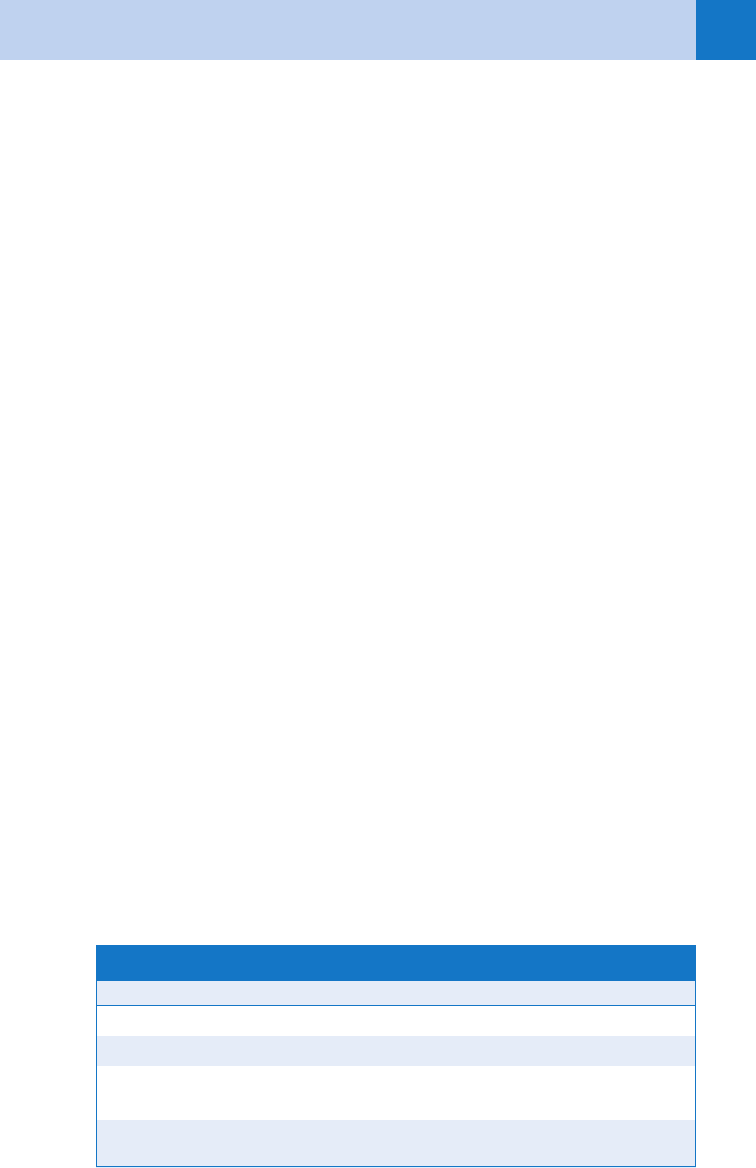

Score 1 2 3

Resp Rate

2–3 y #34 35–39 40

4–5 y #30 31–35 36

6–12 y #26 27–30 31

.12 #23 24–27 28

Oxygen

requirement

.90% on room air 85%–90% on room

air

,85% on room air

Auscultation Normal or end-

expiratory wheeze only

Expiratory wheezes Inspiratory/Expiratory

wheezes or decreased

breath sounds

Retractions 0–1 site 2 sites 31 sites

Dyspnea Speaks in sentences,

coos, babbles

Speaks in partial

sentences, short cry

Single words, short

phrases, grunting

Table 62-3. PEDIATRIC ASTHMA SCORE

Modified from Kelly CS, Anderson CL, Pestian JP, et al: Improved outcomes for hospitalized asthmatic

children using a clinical pathway. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 84:509–516, 2000.

Chapter 62 ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISORDERS IN CHILDREN 439

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Beers SL, Abramo TJ, Bracken A, et al: Bilevel positive airway pressure in the treatment of status asthmaticus

in pediatrics. Am J Emerg Med 25:6–9, 2007.

2. Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, et al: A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for

mild croup. N Engl J Med 351:1306–1313, 2004.

3. Dobrovoljac M, Geelhoed GC: An update highlighting the effectiveness of 0.15 mg/kg of dexamethasone.

Emerg Med Australas 21:309–314, 2009.

4. Greenberg RA, Kerby G, Roosevelt GE: A comparison of oral dexamethasone with oral prednisone in pediatric

asthma exacerbations treated in the emergency department. Clin Pediatr 47:817–823, 2008.

5. Hartling L, Wiebe N, Russell K, et al: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of

epinephrine for the treatment of acute viral bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157:957–964, 2003.

6. King VJ, Viswanathan M, Bordley WC, et al: Pharmacologic treatment of bronchiolitis in infants and children:

A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158:127–137, 2004.

7. Mitra A, Bassler D, Goodman K, et al: Intravenous aminophylline for acute severe asthma in children over two

years receiving inhaled bronchodilators. The Cochrane Library, Vol. 3, 2005.

8. Rowe BH, Bretzlaff JA, Bourdon C, et al: Magnesium sulfate for treating exacerbations of acute asthma in the

emergency department. The Cochrane Library, Vol. 3, 2005.

9. Subcommittee on the diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 118:1774–1793, 2006.

10. Wagner T: Bronchiolitis. Pediatr Rev 10:386–394, 2009.

11. Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, et al: Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children

with status asthmaticus: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 6:142–147, 2005.

12. Zhang L, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Wainwright C, et al: Nebulized hypertonic saline for acute bronchiolitis in infants.

The Cochrane Library, Vol 4, 2008.

also be given subcutaneously. These medications, which should not interrupt inhaled therapy,

require monitoring of cardiac function and serum potassium levels.

28. What should I do if my patient is going into respiratory failure?

Consider treatment with magnesium, terbutaline, and epinephrine. Bilevel positive airway

pressure (BiPAP; set initially at 10/5) has been shown in small studies to improve respiratory

rate and oxygenation in children. If intubation is necessary, ketamine (in conjunction with a

paralytic) stimulates the release of catecholamines causing bronchodilation, making it the

inductive agent of choice (dose: 1-2 mg/kg IV). To optimize oxygenation and prevent

barotrauma, initial ventilator settings should be set to a reduced rate of 8 to 12 breaths

per minute, allowing for permissive hypercapnia.

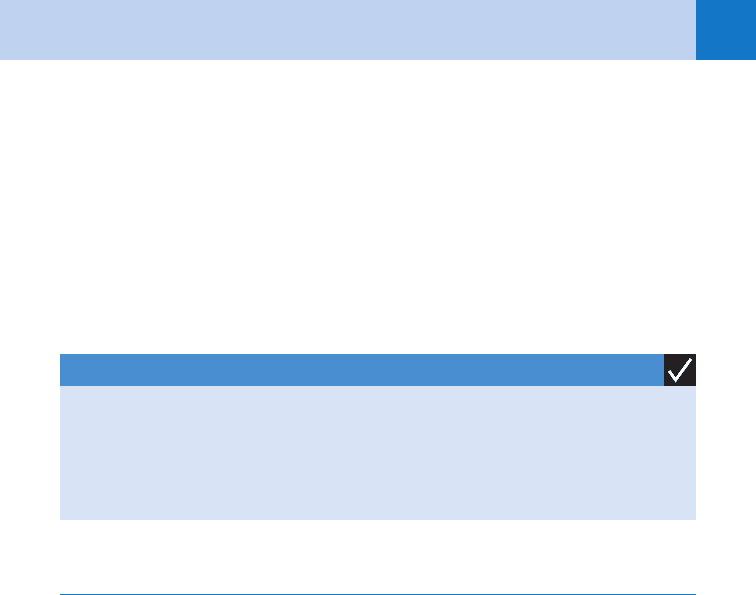

KEY POINTS: EVALUATION OF RESPIRATORY DISORDERS

1. Observation prior to auscultation helps to localize and differentiate etiologies of pediatric

respiratory complaints.

2. Foreign bodies should be suspected in any child presenting with signs of airway obstruction.

3. Labs and radiographs are not routinely indicated in many childhood respiratory disorders.

440

PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS

AND DEHYDRATION

CHAPTER 63

Joshua S. Easter, MD

1. What are the common causes of abdominal pain in children?

Abdominal pain is a common pediatric complaint, the differential for which is guided by age of

the patient, history, and physical examination with or without diagnostic studies (Table 63-1).

2. Can you determine if a child is dehydrated based on the history and physical

examination?

Historical factors, such as the number of wet diapers, frequency of vomiting or diarrhea, and

amount of oral intake, should be used in conjunction with other physical signs to assess

dehydration. The presence of sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, cool extremities, weak

pulses, decreased tears, increased heart rate, and sunken fontanelle are often unreliable.

Capillary refill time (normally less than 2 seconds), skin turgor, and hyperpnea are better

indicators of severe dehydration.

3. How do you manage the different levels of dehydration?

n

Mild or moderate dehydration: Oral rehydration is the ideal treatment. Using the World

Health Organization (WHO) solution or Pedialyte, the patient drinks 50 to 100 (mL/kg) over

4 hours in the form of 5 mL aliquots administered via a medicine dropper or syringe every

5 minutes. An alternate and more simplified strategy involves administration of 1 mL/kg

every 5 minutes for 4 hours. If the child vomits, wait 15 minutes and try again. These

regimens have similar success rates to intravenous hydration and shorter times to initiation

of therapy and shorter ED length of stay.

n

Severe dehydration or patients failing oral rehydration: These children are ill appearing

and should receive intravenous fluids. They often require multiple 20-mL/kg boluses to

compensate for their dehydration. By avoiding fatty acid breakdown and ketosis, dextrose

containing fluids may lead to more rapid improvement in vomiting than normal saline.

4. How are maintenance fluids determined in a child?

Maintenance fluids per hour are calculated based on weight in kilograms using the 4-2-1 rule:

4 mL/kg for the first 1 to 10 kg, an additional 2 mL/kg for the next 11 to 20 kg, and 1 mL/kg

for every additional kg.

5. What are potential causes of vomiting without diarrhea in children?

The differential includes early gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, appendicitis, diabetic

ketoacidosis, otitis media, pneumonia, strep pharyngitis, testicular or ovarian torsion,

meningitis, and head injury.

6. How do you differentiate between gastroenteritis and more severe abdominal

pathology?

This may be difficult and often requires a period of observation in the ED for other developing

signs or symptoms. Focal tenderness in the abdomen makes gastroenteritis less likely.

7. What diagnostic studies should be obtained on children with gastroenteritis?

Most require no tests. Infants with prolonged or severe symptoms can deplete their

glycogen stores and therefore should have a bedside glucose test. Electrolyte studies,

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION 441

looking for hypernatremia or renal insufficiency, may be considered for ill-appearing

children. In the setting of hypoglycemia, the infant or child should be given 4 mL/kg of

dextrose 10% (if younger than 3 months old) or 2 mL/kg of dextrose 25% (if more than

3 months old).

8. How do you differentiate between bacterial and viral causes of diarrhea?

n

Viruses cause the majority of diarrhea in children, with rotavirus the most common agent

in younger children and Norwalk virus in older children. Viral diarrhea tends to produce

voluminous watery diarrhea with diffuse abdominal cramping.

n

Bacterial diarrhea typically causes lower abdominal pain and bloody or mucousy stool.

However, these history and physical examination findings cannot reliably differentiate bacterial

from viral diarrhea. Stool cultures should be obtained in patients with significant

comorbidities, ill appearance, high fever, bloody stools, severe cramping, recent antibiotic use,

travel, or exposure to a patient with a known bacterial diarrhea.

KEY POINTS: GASTROENTERITIS AND DEHYDRATION

1. Young children with gastroenteritis can become dehydrated easily.

2. Vomiting in the pediatric population has a broad differential.

3. Most children can be successfully rehydrated without intravenous fluids.

9. Should narcotics be withheld from children with acute abdominal pain while

awaiting a surgical evaluation?

No. Multiple studies have shown diagnostic accuracy from physical examination increases

when patients’ pain is controlled.

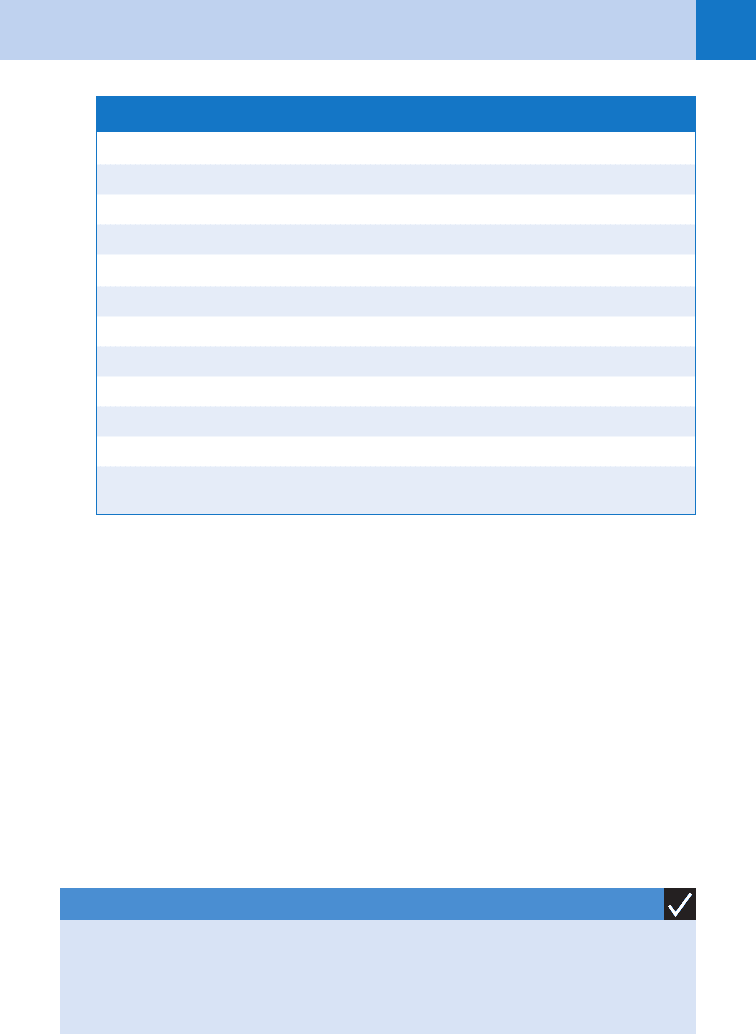

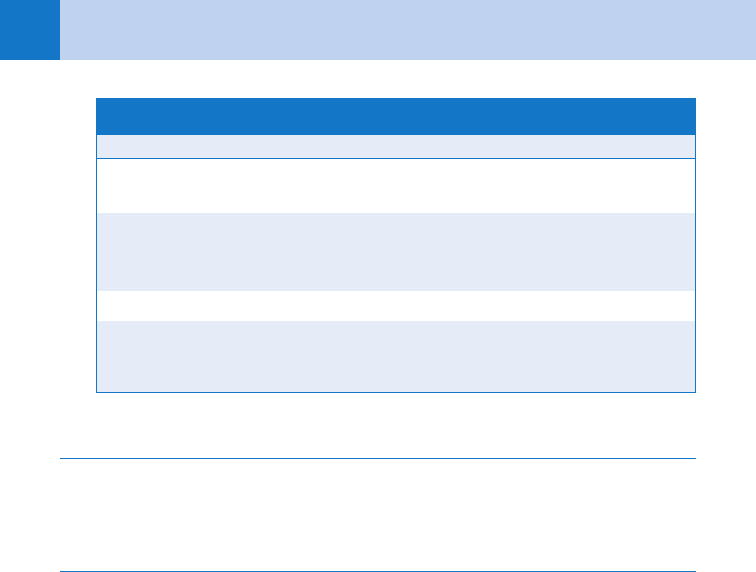

Neonate 2 months–2 years

Malrotation Incarcerated hernia

Necrotizing enterocolitis Intussusception

Testicular torsion Urinary tract infection

2–5 years 6–18 years

Appendicitis Appendicitis

Foreign body Ovarian/testicular torsion

Intussusception Kidney and gallbladder stones

Ovarian torsion Diabetic ketoacidosis

Urinary tract infection Ectopic pregnancy

Strep pharyngitis Pelvic inflammatory disease

Henoch-Schönlein purpura Gallbladder disease

TABLE 63-1. DIFFERENTIAL OF NONTRAUMATIC ABDOMINAL PAIN BY AGE

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION442

10. How does appendicitis present in younger children?

The diagnosis of appendicitis is commonly missed in younger children who often present with

nonspecific symptoms. Vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea, irritability, and right hip pain

are some typical presentations, often attributed to other causes. Similarly, their physical

examinations frequently reveal diffuse abdominal tenderness or abdominal distention, while pain

localized to the right lower quadrant is an infrequent presentation. Appendicitis in the infant is

typically recognized only after perforation, which occurs in 70% to 95% of these cases.

11. What physical examination findings are found in older children with

appendicitis?

The most common findings are tenderness in the right lower quadrant and involuntary

guarding. Rovsing’s sign (pain in the right lower quadrant with palpation of the left lower

quadrant), obturator sign (pain with internal rotation of the flexed hip), and the psoas sign

(pain with extension of the right thigh) have not been shown to be particularly sensitive or

specific for appendicitis in children. Their absence should not be used to rule out appendicitis.

12. What laboratory tests are helpful in children with appendicitis?

If the history and physical examination are highly suspicious for appendicitis, no further tests

are required and a surgeon should be consulted.

The white blood cell count (WBC) does not provide useful levels of sensitivity and

specificity. A WBC .10,000/mm

3

has a sensitivity of 88%, but specificity of 53%; a WBC

.15,000/mm

3

improves specificity to over 60%, but the sensitivity declines to 19%. An

elevated C-reactive protein has similar sensitivity and specificity to a WBC.10,000, with even

lower sensitivity and specificity when measured in the first 12 hours. A positive urinalysis

cannot exclude appendicitis; 30% of children with appendicitis have pyuria or bacteriuria.

13. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the different radiographic tests

for appendicitis?

n

Plain films: Insensitive and nonspecific, these are normal in 82% of children with

appendicitis.

n

Ultrasound (US): If available, US should be the initial study of choice in children with

suspected appendicitis since lack of peritoneal fat favors ideal imaging with this modality.

In experienced hands, US provides a high sensitivity (71%–92%) and specificity (96%–

98%). Appendicitis will show an appendiceal diameter .6 mm, wall thickness .2 mm,

obstruction of the appendiceal lumen, appendicolith, high echogenicity surrounding the

appendix, or pericecal free fluid. Obesity, uncooperative patients, or atypical locations of the

appendix may limit this study.

n

Computerized tomography (CT): With CT, appendicitis shows an appendiceal diameter

.6 mm, wall thickness .1 mm, periappendiceal fat stranding or fluid collection, or an

appendicolith. In children, CT has a higher sensitivity (94%–99%) and specificity

(87%–99%) than US. Higher cost, potential need for sedation, and radiation exposure are

the major drawbacks of CT.

KEY POINTS: APPENDICITIS

1. Younger children have atypical presentations of appendicitis, resulting in delays in diagnosis

and high perforation rates.

2. Lab tests are relatively non-specific and should not be used to exclude a diagnosis of

appendicitis.

3. In equivocal cases, ultrasound should be the first imaging study in children with suspected

appendicitis.

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION 443

14. How does intussusception present?

Intussusception, an invagination of one portion of bowel into a distal segment (most commonly

at the ileocecal junction), afflicts children most commonly between infancy and 3 years of age.

The classic triad of colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, and bloody stool is present in less than

25% of children. Intermittent periods of irritability, where children may pull their knees up

toward their chest, is often the only symptom. Although often cited in the literature, currant

jelly stools are a late, rare, and ominous finding from bowel ischemia. Younger children may

present with nonspecific findings such as altered mental status or lethargy.

15. How do you diagnose intussusception?

The classic crescent sign on plan radiography from the intussuscepting mass is rarely seen.

Nevertheless, abdominal X-rays can be helpful in low risk cases; when air is seen in the

ascending colon on at least two of three views (i.e., supine, prone, and lateral decubitus),

likelihood of intussusception is substantially reduced. US may identify a donut or target sign,

yielding a sensitivity and specificity of over 90%. Air enema may be utilized to both diagnose

and treat intussusception.

16. How should intussusception be treated?

Air enemas provide equivalent success rates to contrast enemas with less radiation exposure.

Due to a 1% risk of perforation with enema reduction, a surgeon should be available. Because

up to 10% of patients will have recurrence within the first 24 hours, caregivers must ensure

appropriate family education on strict return precautions. Shock or suspected intestinal

perforations necessitate surgical consultation for operative repair.

17. What is the significance of bilious emesis in a neonate?

Bilious emesis in a neonate is a surgical emergency until proven otherwise because it could

represent malrotation with volvulus (midgut volvulus). Congenital malrotation of the midgut

predisposes the bowel to twisting on itself, leading to bowel obstruction and vascular

compromise, with bowel necrosis developing in as little as 2 hours.

Midgut volvulus classically presents with sudden onset of bilious emesis and

abdominal pain; however, early in the course of illness, more than half of patients have

normal abdominal examinations and one third have abdominal distention without

tenderness. Thus, all infants with bilious emesis should undergo diagnostic testing

regardless of their abdominal examinations. Although X-rays can show small bowel

obstruction, a double bubble sign, or paucity of distal bowel gas with volvulus, imaging is

often normal. An upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series with contrast is the gold standard

because it will show a cork screwing of contrast or the duodenojejunal junction not

crossing to the left of the vertebral column.

If volvulus is suspected, intravenous fluids should be given, a nasogastric tube inserted,

broad-spectrum antibiotics administered, and surgical consultation obtained immediately.

18. What characteristics of a patient’s history help differentiate pyloric stenosis

from other causes of vomiting in infants?

True projectile emesis, where the vomitus shoots away from the patient, is most commonly

found with pyloric stenosis. A hypertrophy of the pylorus develops between 1 to 5 weeks of

age. Initially, infants vomit only at the end of feeds, later developing more classic projectile

vomiting. Unlike more severe conditions such as malrotation, emesis is usually nonbilious due

to the stenosis being proximal to the duodenum. The patient will remain hungry and continue

attempts to feed. Unlike more benign causes of vomiting such as reflux, the patient does not

gain weight appropriately.

19. What diagnostic findings arise with pyloric stenosis?

Vomiting leads to loss of hydrogen ions from the stomach, the kidneys attempt to conserve

sodium in a response to dehydration, spilling potassium into the urine, all resulting in a

hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis.

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION444

The diagnostic study of choice is an US, which has a sensitivity and specificity of nearly

100%. In pyloric stenosis, the pyloric wall is greater than 4 mm wide or 14 mm long. If the

US is equivocal, then an UGI will classically show a string sign as contrast travels through the

narrowed pylorus.

Patients with pyloric stenosis require rehydration and eventual surgical correction,

although in developing countries often patients can be supported long enough to allow the

hypertrophy to resolve without surgery.

20. Are inguinal hernias dangerous?

One percent to 2% of children develop inguinal hernias, with 10% ultimately incarcerating.

This happens most commonly in children younger than 1 year of age. If the incarceration

persists, the bowel can strangulate, cutting off its blood supply and leading to bowel

obstruction or necrosis.

Unless bowel necrosis is already suspected, manual reduction can be attempted on

incarcerated hernias to prevent strangulation. With the patient in Trendelenburg, using

constant gentle pressure, 95% of inguinal hernias can be reduced and these patients can be

safely discharged for outpatient surgical repair. If necessary, sedation can be used to assist in

pushing the hernia back through the inguinal ring. If reduction is unsuccessful or

strangulation suspected, immediately consult a surgeon.

21. What is the difference between a hernia and a hydrocele?

A hydrocele arises from an incomplete obliteration of the processus vaginalis, which allows

the peritoneum to translocate into the scrotum. Unlike hernias, these can be transilluminated.

In addition, they are readily separable from the testes. If you cannot differentiate a hydrocele

from a hernia on examination, you can obtain a scrotal ultrasound. Hydroceles are benign and

often resolve spontaneously.

KEY POINTS: SURGICAL EMERGENCIES IN YOUNG CHILDREN

1. Intussusception rarely presents with the classic triad of colicky abdominal pain, currant jelly

stools, and vomiting. More often only intermittent irritability is present.

2. Bilious emesis in a neonate is a surgical emergency until proven otherwise.

3. Infants with pyloric stenosis have projectile emesis but remain hungry and interested in

feeding.

22. Why is jaundice concerning in a neonate?

While newborns often have physiologic jaundice that is self-limited, significantly elevated

levels of unconjugated bilirubin can lead to kernicterus, with resulting deafness,

developmental delay, or death. These elevated levels can arise from a myriad of causes

including Rh or ABO incompatibility, prematurity, polycythemia, intestinal obstruction, sepsis,

or dehydration. All patients with visible jaundice need a documented bilirubin level, and if

elevated a search made for etiology. This may include a blood type, Coomb’s test and

complete blood count (CBC). Patients with elevated age-specific bilirubin levels may require

phototherapy, with exchange transfusion considered for marked elevations (.25 mg/dl).

23. Is it normal for a child to have constipation?

It is normal for infants to strain during bowel movements, but parental anxiety over infant

straining or lack of frequent bowel movements may lead to an ED visit. Bottle-fed infants can

often pass as few as one stool every other day. Breastfed infants may pass a stool with each

feed or as infrequently as once every 7 to 10 days. As infants age, it is typical for stool

frequency to decrease; by 4 years of age children average 1.2 bowel movements per day.

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION 445

Rarely, infants presenting with constipation have more serious conditions. A thorough

history and physical examination can give clues to some of these entities: onset of symptoms

in the first week of life (Hirschsprung’s), abnormal tone, lethargy and weak cry (botulism and

hypothyroidism), or worrisome abdomen examination (volvulus).

The diagnosis of constipation should be based on difficulty or pain with passage of a

bowel movement rather than absolute frequency. In older children, constipation most

commonly arises with changes in diet or inadequate fluid intake. School-age children may

have behavioral issues, such as a fear of having a bowel movement at school that ultimately

affects their bowel patterns.

24. How can you treat constipation in the ED?

Most patients with constipation not arising from a serious etiology can be managed as

outpatients. A trial of a soy-based formula may relieve constipation in infants with suspected

cow’s milk intolerance. A one-time enema can occasionally help, but hypertonic phosphate

enemas and tap water enemas should be avoided because they can cause severe electrolyte

abnormalities. Mineral oil (1–4 ml/kg/dose), lactulose (1–2 ml/kg/dose), milk of magnesia

(1–3 ml/kg/dose), or MiraLax (mix 17g in 8 oz fluid) can be administered in the short term.

Long-term management includes increasing fluid intake and adding fiber to the diet.

25. What is a Meckel’s diverticulum?

It is a remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct in children. It is the most significant cause of

painless rectal bleeding and can lead to obstruction or intussusception. Sixty percent contain

heterotopic gastric, pancreatic, or endometrial tissue. If suspected, a technetium 99m

Meckel’s scan can identify ectopic gastric mucosal tissue, thus making the diagnosis.

26. What is Meckel’s rule of twos?

Meckel’s diverticulum occurs in 2% of the population; 2% of patients will manifest symptoms;

the diverticulum is typically 2 inches long and within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve; average age

at presentation is 2 years.

27. How do you manage an ingested gastrointestinal foreign body?

The management of foreign bodies depends on the nature of what was ingested and its

location. Any patient with a known ingestion and hematochezia, melena, or signs of an acute

abdomen requires immediate surgical consultation. See Table 63-2.

28. What are the possible complications of an esophageal foreign body?

Airway obstruction, esophageal stricture, esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, or

paraesophageal abscess.

29. What diseases are associated with these classic findings on X-ray?

See Table 63-3.

Emergent Endoscopy Gastrointestinologist Consultation

Sharp objects in the esophagus Button battery past the esophagus

Button battery in the esophagus Sharp objects past the pylorus

Objects causing difficulty controlling secretions

or breathing

Long objects past the pylorus

(.5 cm)

Objects in the esophagus for more than 24 hours Multiple magnets

TABLE 63-2. MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL FOREIGN BODIES

Chapter 63 PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS AND DEHYDRATION446

Finding X-ray Description Disease Process

Double Bubble Paucity of gas with air bubble in

stomach and duodenum

Volvulus

Crescent Curvilinear mass often found near

transverse colon beyond hepatic

flexure

Intussusception

Pneumatosis Intestinalis Air in bowel wall Necrotizing enterocolitis

Enlarged pylorus Wall of pylorus .4 mm thick

Canal .14 mm

Pyloric stenosis

TABLE 63-3. RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS IN PEDIATRIC ABDOMINAL PAIN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Gardikis S, Touloupidis S, Dimitriadis G, et al: Urological symptoms of acute appendicitis in childhood and

early adolescence. Int Urol Nephrol 34(2):189–192, 2002.

2. Grönroos JM: Do normal leucocyte count and C-reactive protein value exclude acute appendicitis in children?

Acta Paediatr 90(6):649–651, 2001.

3. Horwitz JR, Gursoy M, Jaksic T, et al: Importance of diarrhea as a presenting symptom of appendicitis in very

young children. Am J Surg 173(2):80–82, 1997.

4. Kim MK, Strait RT, Sato TT, et al: A randomized clinical trial of analgesia in children with acute abdominal

pain. Acad Emerg Med 9(4):281–287, 2002.

5. Kokki H, Lintula H, Vanamo K, et al: Oxycodone vs placebo in children with undifferentiated abdominal pain:

a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of the effect of analgesia on diagnostic accuracy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc

Med 159(4):320–325, 2005.

6. Kwok MY, Kim MK, Gorelick MH: Evidence-based approach to the diagnosis of appendicitis in children.

Pediatr Emerg Care 20(10):690–698, 2004.

7. Levy JA, Bachur RG: Intravenous dextrose during outpatient rehydration in pediatric gastroenteritis. Acad

Emerg Med 14(4):324–330, 2007.

8. Roskind CG, Ruzal-Shapiro CB, Dowd EK, et al: Test characteristics of the 3-view abdominal radiograph series

in the diagnosis of intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care 23(11):785–789, 2007.

9. Rothrock SG, Green SM, Hummel CB: Plain abdominal radiography in the detection of major disease in

children: a prospective analysis. Ann Emerg Med 21(12):1423–1429, 1992.

10. Spandorfer PR, Alessandrini EA, Joffe MD, et al: Oral versus intravenous rehydration of moderately

dehydrated children: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 115(2):295–301, 2005.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The editors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Mark Anderson, MD, author of this chapter

in the previous edition.

447

PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

CHAPTER 64

Roger M. Barkin, MD, MPH, FACEP, FAAP

1. Are infectious diseases important to recognize in the pediatric patient?

Infectious diseases account for a significant percentage of pediatric visits to the ED for acute

illness. Although most conditions are self-limited and infrequent, some infections are

significant in that they may be multisystem or life threatening, requiring consideration in the

differential diagnosis of many presenting complaints.

2. What is the mechanism of spread of measles (rubeola)?

By direct contact with infectious droplets or airborne dissemination.

3. What is the incubation period for measles?

From exposure to the onset of symptoms, 8 to 12 days. It is 14 days from exposure to the onset

of the rash. Patients are contagious 1 to 2 days before they become symptomatic and 4 days

after the rash appears.

4. List the common signs and symptoms of patients with measles.

n

High fever.

n

Three Cs: Conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough may be observed.

n

Rash: Discrete red maculopapular rash first appears on the forehead, becoming coalescent

as it spreads down the trunk to the feet by the third day of the illness. The rash fades in the

same head-to-feet pattern as it appeared.

n

Koplik’s spots: 1- to 3-mm bluish white spots on a bright red surface, which appear first on

the buccal mucosa opposite the lower molars. They are a pathognomonic exanthem of

measles. They appear approximately within 48 hours after the onset of symptoms. The

spots may spread to involve the buccal and labial mucosa and disappear on the second day

after the onset of the rash.

n

Photophobia may be noted.

5. Name the complications of measles.

Otitis media and bronchopneumonia. Encephalitis may occur as well.

6. What is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis?

A rare degenerative central nervous system disease caused by a latent measles infection,

occurring an average of 10 years after a primary measles illness. Patients have progressive

intellectual and behavioral deterioration and convulsions. This disease is not contagious.

7. Describe the exanthem seen in rubella. Why is it also called 3-day measles?

Numerous discrete rose-pink maculopapules first appear on the face and, as in rubeola,

spread downward to involve the trunk and extremities. The rash on the face fades on day 2,

and the rash on the trunk becomes coalescent. By the third day, the rash disappears, which is

why rubella is also called 3-day measles. Rubella is now rarely reported in the United States

secondary to the efficacy of immunizations.

8. What are Forschheimer spots?

Pinpoint red macules on the soft palate seen early in rubella; however, in contrast to Koplik’s

spots, they are not pathognomonic.