Marshall L. Stoller, Maxwell V. Meng-Urinary Stone Disease

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

10 Master, Meng, and Stoller

Several remedies for bladder calculi from folk medicine are described in the Talmud

(Gittin, folio 69b). One example illustrating the lack of understanding of pathophysiol-

ogy was to “take a louse from a man and a woman and hang it on the penis of a man and

the corresponding place in a woman; and when he urinates he should do so on dry thorns

near the socket of the door” (12). Surprisingly, this “remedy” remained in the medical

armamentarium through the Middle Ages. The extreme suffering generated by stone

disease and the importance of stone prevention is evidenced by finding recipes against

kidney stones in the Croatian prayerbook (13).

The use of surgical instrumentation in the treatment of urinary stone disease has a

checkered history, with admonitions against surgery from the start. The great Hippocrates

(460–370 BC), who was familiar with the pathology related to urinary tract stones,

included a passage regarding their treatment in the original Hippocratic Oath:

“I will not cut persons laboring under the stone, but will leave this work to be done by

men who are practitioners of this work.” (Adams translation) (14).

Of course, this statement can be interpreted two ways. Either the removal of stones

was considered too lowly a craft for physicians, or conversely lithotomists must have

possessed a fair degree of skill, or Hippocrates would not have recommended that only

practitioners of the craft perform the delicate surgery.

Lower Urinary Tract

URETHRAL

Possibly the earliest instrument for the treatment of stone disease could be thought of

as the urethral catheter. The purpose of the catheter was to bypass obstruction thus

permitting drainage. The word catheter is derived from the Greek cathienal, “to send

down,” although some ascribe it incorrectly to cathatos, which means perpendicular

(15). Initially, in an effort to bypass the obstruction resulting from the calculus in the

urethra or at the bladder neck, ancient Egyptians first used hollow reeds and curled-up

palm leaves, but later history records Egyptians using bronze and tin for making cath-

eters, knives, and sounds as early as 3000

BC. The ancient Hindus used tubes of gold, iron,

and wood for dilating the urethra at least before 1000

BC (16). The Chinese used a

lacquer-coated tubular leaf of the onion plant Allium fistulosum to make catheters as

early as 100

BC (17). Metal catheters and sounds made of bronze were found in the ruins

of Pompeii, which was buried in 79

AD (18). Although the catheters found at Pompeii

were doubly curved, all other ancient catheters and sounds had one common character-

istic: they were made straight and rigid without consideration for anatomic structure of

the posterior urethra. Surprisingly, the logical idea of making catheters curved was not

rediscovered until literally hundreds of years later. During the 10th century, Islamic

surgeons used rigid silver catheters and also catheters made of skins. Avicenna (980–

1030

AD) used sea animal skins stuck together with cheese glue and also recommended

lubricating the urethra with soft cheese before rigid catheterization. Many others tried

different materials that were both simultaneously stiff and malleable including silver,

copper, brass, ivory, pewter, and lead. Lack of the ability to create an indwelling catheter

was a continuing problem with all of these designs but nevertheless provided relief to

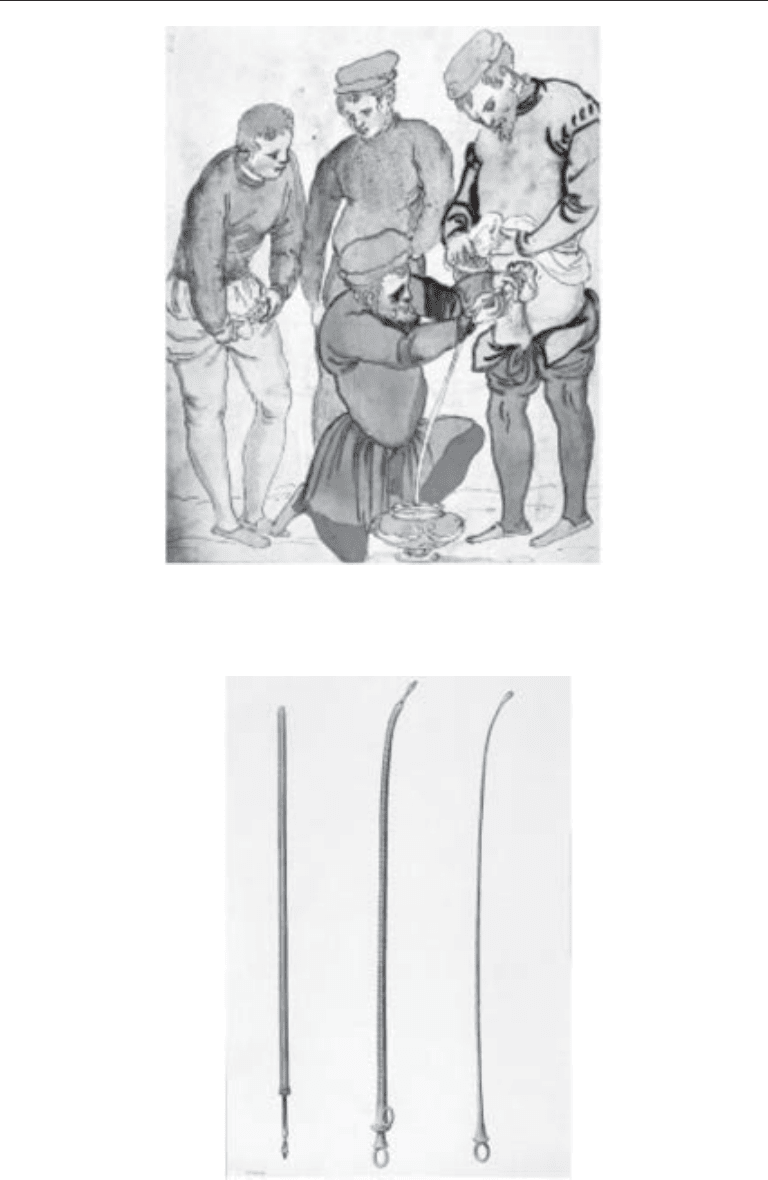

patients (Fig. 2). In the early part of the 18th century, a German anatomist, Lorenz

Heister (1683–1758), had catheters made of silver in the shape of the natural curve of the

prostatic urethra (Fig. 3). The true development of the modern catheter is felt to come

from Heister’s design and was perfected in the form of the “coude” (French, meaning

Chapter 1 / Stone Nomenclature and History 11

Fig. 3. Silver catheters showing evolution in design with the two on the right being bent to

simulate the natural curve of the prostatic urethra.

Fig. 2. Sixteenth century itinerant barber-surgeons catheterized grateful patients to relieve ob-

struction caused by bladder stones, as illustrated in a Italian medical picture book by Henricus

Kullmaurer and Albert Meher.

12 Master, Meng, and Stoller

elbow [noun], or bent [adjective]) catheter by the eminent French surgeon Louis Mercier

(1811–1882), although the literature still contains spurious assertions that a certain

Emile Coude was responsible (19).

The first flexible catheters were made of wax-impregnated cloth and molded on a

silver sound created by Frabricius, professor of surgery in Padua, in 1665. These cath-

eters were not very durable and softened rapidly, thus losing the ability to maintain a

patent lumen. Modern flexible catheters, basic prototypes of the ones used today, were

first made with the introduction of elastic gum, derived from the latex sap of the Hevea

tree species in 1735 (20). These were far more comfortable than the rigid catheters, but

still suffered from problems of extreme stickiness in hot weather and brittle stiffening

in cold weather. The ability to transform this elastic gum into a durable and versatile

substance that did not have temperature dependence was discovered by Charles

Goodyear in 1839, who termed this process vulcanization. After methods were devel-

oped for stabilizing the natural latex and preventing it from coagulating, rubber prod-

ucts could be made over a mold dipped into a vat of latex. This rubber catheter was

relatively durable, flexible, and therefore easily introduced and comfortably retained.

Its introduction marked the true beginning of the modern urinary catheter. This catheter

still required external appliances to hold it in place, such as taping it to the penile shaft

or suturing to the labia in women. In 1822, Ducamp used submucosal layers of ox

intestines, which were tied on to the catheters as inflatable balloons to hold a catheter

in place. In 1853 Reybard devised a catheter that incorporated a separate balloon chan-

nel. A growing surge of transurethral surgery led to the need to secure hemostasis and

finally resulted in F. E. B. Foley, an American urologist, devising the modern balloon

catheter in the 1930, which was distributed by Bard in 1933 (21). Modern 20th-century

developments in catheters have centered mostly on the use of different materials, like

silicone, to reduce urethral toxicity from latex.

A Parisian instrument maker, Joseph Frederick Benoit Charriere (1803–1876), devised

a sizing system for urologic instruments commonly called the French scale in the United

States, which is based on progressive diameter sizes differing from each other by one-

third of a millimeter, i.e., 1 mm = 3 French (Fr) or 0.039 inches (22).

It was known for millennia that merely pulling out stones lodged in the penile urethra

could result in irreversible urethral injury. In fact, Celsus himself, devotes a large section

of his book, De Medicina, to the removal of urethral calculi. He describes first using a

scoop, but failing that, urethrolithotomy was performed with a sharp knife. The urethra

and skin edges were left open to heal by secondary intention. An ingenious prevention

of fistula formation was to stretch the penile shaft skin distally and push the glans

proximally so that after the incision to remove the stone, the relaxed skin would result

in nonoverlapping urethral and skin openings (23).

B

LADDER

Perineal Lithotomy

The operation for bladder stone is one of the oldest recorded surgical techniques

apart from trepanning and circumcision (20). Patients were understandably reluctant to

undergo surgery, given the absence of anesthesia and the very high procedure-related

mortality, as described in the following paragraphs. Only severe, prolonged, insuffer-

able pain related to the stone made patients submit to the acute pain of the knife. The

literature is replete with descriptions of special instruments, knives, lancets, and gorgets

with unique blades for opening the bladder through the prostatic urethra. Medial litho-

Chapter 1 / Stone Nomenclature and History 13

tomy (cutting on the gripe) is the oldest variety of the perineal operation, but even

Celsus, in approx 50

AD, recognizing the great danger of rectal injury, deflected the

inferior end of the perineal incision toward the left ischial tuberosity before incising the

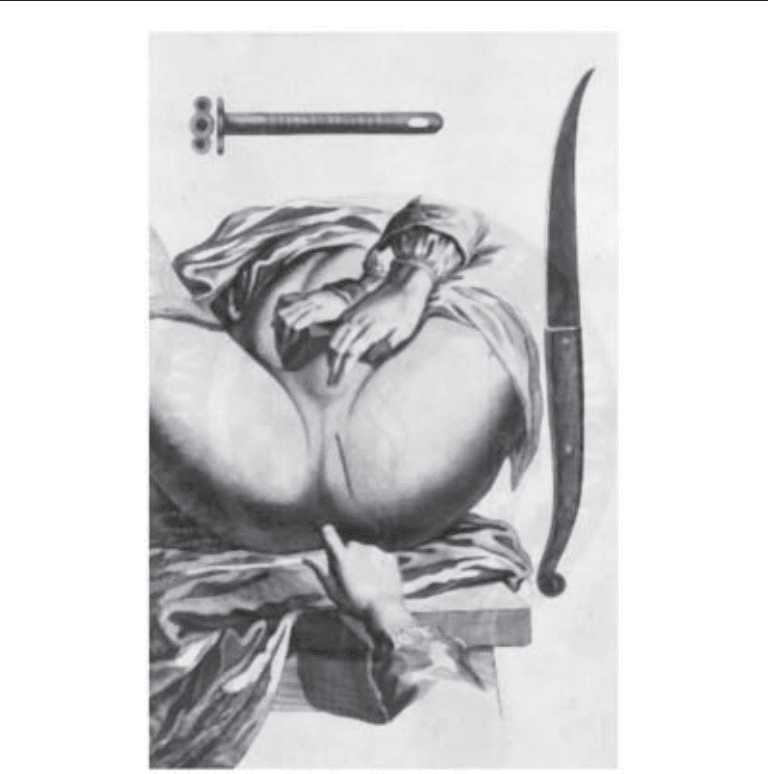

bladder. In perineal lithotomy of the “small apparatus” a staff or sound was passed

through the urethra into the bladder (Fig. 4). This sounding was the method employed

to confirm the presence and location of vesical stone. With the patient in a semisitting

posture, the tip of the sound was maneuvered to bring the stone down to the lowest point

in the bladder. When the perineal incision was made the surgeon felt for the groove on

the convex side of the staff as a guide for the incision into the membranous urethra and

prostate. When an assistant held the urethral staff, the surgeon could cut directly onto

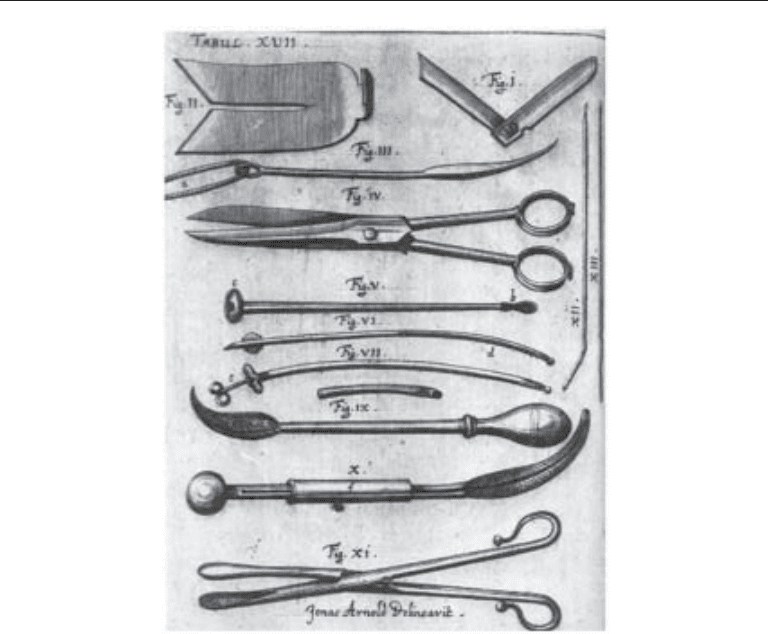

the stone. Perineal lithotomy using the “grand apparatus” of Mariano Santo came next

in 1535 (Fig. 5). Instruments, forceps, and scoops, rather than the finger, were inserted

Fig. 4. Lithotomy using instruments of the “lesser” apparatus. Note the lateral incision for

lithotomy. Note the sharp bistoury on the right and the cannula at top, which were designed by

M. Fourbert in the 18th century.

14 Master, Meng, and Stoller

through the perineal incision to engage and extricate the stone. In the main, it can be said

that the additional apparatus not only complicated the procedure but added to the

operative risk (24). The sole objective of lithotomy was to relieve the patient of stran-

gury by extracting the stone as quickly as possible through a perineal incision. Opera-

tions were frequently performed in the home. The patient was purged and often bled

before as well as after operation. Bleeding immediately beforehand had the advantage

of producing shock and considerable diminution in sensitivity to pain. As many as five

or more cases were often scheduled for one session. Pouteau, the great 18th-century

French surgeon, described the scenes as an “auto-da-fe affair” (act-of-faith affair). The

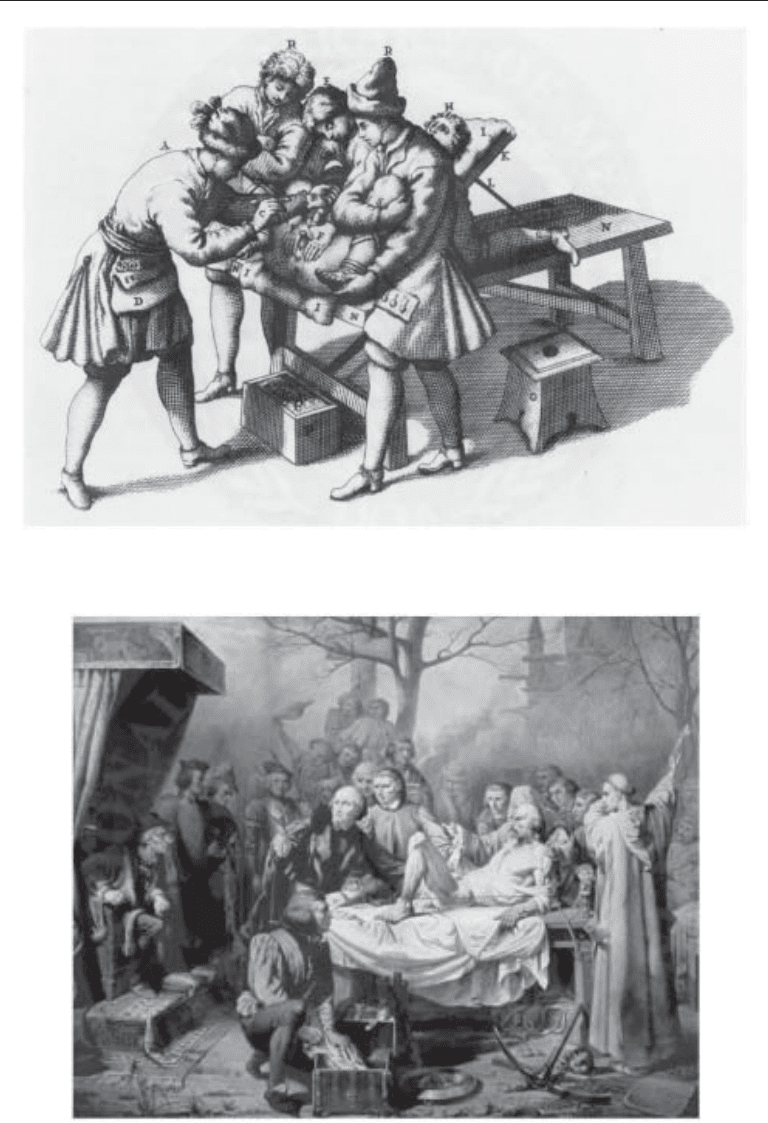

courage and agony of the patient on the lithotomy table, known as the scaffold or Bed

of Misery (Fig. 6), and the boldness and skill of the surgeon were the magnetic attrac-

tions that drew onlookers, both rich and poor (Fig. 7). After the terror and pain of the

operation, the patient usually had a sense of relief as urine escaped through the litho-

tomy wound without initiating attacks of vesical colic. Perineal lithotomy provided the

surgeon a fine opportunity to indulge in showmanship. Sir Astley Cooper often did the

operation in less than a minute and the average maximum time in a surgical editorial in

1828 was about 6 min (24).

Fig. 5. Elements of the “major” apparatus used for lithotomy in the 17th century. Note the

multiplicity of knives, spatulas, and hooks used for cystolithotomy in the later period compared

with that in Figure 4, which just used a knife and a cannula.

Chapter 1 / Stone Nomenclature and History 15

Fig. 7. Lithograph titled, “The earliest operation for the stone,” by Rivoulon. The patient is lying

on a platform and the physician is performing an operation before a large crowd, which includes

King Louis XI of France, seen seated on the left, intently watching the showmanship. This

fanciful lithograph has little relation to the pain the patient suffered during the stone removal.

Fig. 6. Lithotomist at work, ca. 1700. Two assistants are holding the legs in lithotomy position,

while a third pushes on the suprapubic region to keep the stone fixed in place at the bladder neck.

16 Master, Meng, and Stoller

From the mid-16th century well into the 18th, a brand of self-made stone cutters,

“specialists” who acquired art through apprenticeship, were the chief lithotomists.

Without formal training, they usually practiced poor operative technique and some were

charlatans (25). Mortality was high, approx 18 to 53%. Extravasation of infected urine

into the paravesical tissues was often the reason for death, rather than hemorrhage. Those

who cut too widely were known to lacerate the internal pudendal artery, often resulting

in exsanguination. Interestingly, there were a few outliers, most spectacularly, Pouteau,

a notable French surgeon of the 18th century, whose mortality rate was only 2.5%. This

was achieved a century before the development of antisepsis by his strict adherence to

the importance of keeping hands clean and the use of disposable paper dressings.

Strangely, published accounts of mortality even during the antiseptic era were almost as

high as the nonantiseptic era, in the range of 10% (24). One hypothesis is that the open

wound management after vesical incision essentially allowed for irrigation of the wound

by urine. It is interesting that the morbidity and mortality associated with this operation

was so high that some of the first informed-consent documents were associated with

lithotomy (26). The first suprapubic lithotomy for removal of a bladder stone was carried

out in 1561 by Franco, who performed removal of an egg-sized stone in a 2-yr-old boy,

but did not achieve acceptance as a safe modality at the time, likely because of the

frequent risk of peritoneal injury and septic death (27).

Celsus, Franco, and Cheselden stand out in their periods as the greatest contributors

to the development of lithotomy. The first truly sterile operation for stone was Joseph

Lister’s median lithotomy for vesical calculus on June 4, 1881. He swabbed the wound

with zinc chloride and left it open, but provided a drainage tube to facilitate the escape

of urine. The patient recovered quickly.

Urinary incontinence, occasionally reported after perineal lithotomy in the male, was

so frequent following urethrovesical lithotomy in the female that the procedure came to

be abandoned. Urethral dilatation was substituted because of the distensibility and short-

ness of the female urethra.

Lithotrity/Lithoprisy

The dangers and difficulties of lithotomy were an important spur that drove the devel-

opment of alternative minimally invasive methods of bladder stone extraction.

Ammonius, in 247

BC, is credited with fragmentation of bladder stones by impaling them

with an ice pick-like device passed through a catheter (11). After engaging the stone, a

hammer was used on the pick to fragment the stone. This idea was apparently unpopular

and there is no mention of stone fragmentation for several centuries. Some lithotomists,

such as Elderton in 1819, unsuccessfully tried to fix stones in place by loops of wire

passed through a straight catheter. When the stone was engaged a drill bow was used to

break up the stone (11). Interestingly, some famous self-performed operations for uri-

nary stones did involve lithotrity-type maneuvers, such as that of Colonel Martin of

Lucknow, a layman who in 1782 ingeniously devised instrumentation to file his stone

to small pieces, which he was then able to void (28). The first truly effective drilling

instrument was made by Civale of France and used in 1824. This instrument, known as

a trilabe or lithontripteur, consisted of two straight metal tubes, one inside the other; the

inner had three curved arms that projected when the outer sheath was retracted and by

which the stone was seized. It was held in position by advancing the outer sheath. An iron

rod with a sharp point was passed through the inner tube to bore a hole into the stone This

was uncomfortable for the patient and treatment sessions were limited to 5 min with

Chapter 1 / Stone Nomenclature and History 17

several sessions required to break the stone into small enough fragments that the patient

could void (29). With this minimally invasive approach, mortality was reduced to a mere

3%. Ambroïse Paré put teeth in the blades of his crushing forceps and a thumbscrew in

the handle so as to increase the power of the instrument to crush large stones, but this also

increased mortality. The introduction of ether anesthesia in 1842 allowed surgeons to

perform longer and more precise operations. Bigelow in 1878 added to the development

of this procedure by the use of suction irrigation and renamed the lithotrity procedure

litholapaxy. The use of anesthesia coupled with suction enabled complete removal of the

stone in a single session, which could last 2 h. However, without the ability to visualize

the stone, this technique was not popularized until cystoscopy was developed, where-

upon the lithotrite was combined with a cystoscope into a single instrument.

Cystoscopy

The desire to look into the cavities of the body to diagnose and treat disease occupied

many medical specialists throughout the 18th century, especially as the alternative was

extensive surgery, not yet possible without the development of anesthesia. The first

instruments designed for urologic evaluation were designed for the female, because of

the shorter length and greater diameter of the urethra. Initially various specula were

developed to inspect the female urethra, mostly by dilating it, but they were painful when

widely opened and provided only a limited viewing ability (30). The biggest hindrance

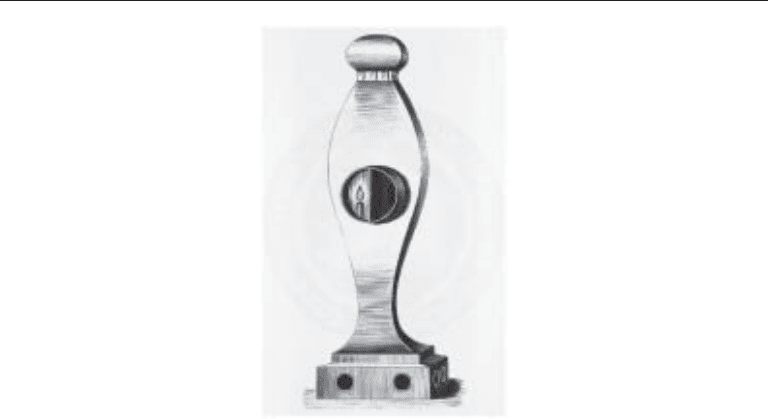

to viewing ability was insufficient illumination. To solve this problem, in 1805 Phillip

Bozzini, from Germany, developed the “lichtleiter,” or light conductor (31). This instru-

ment, made of silver and covered in sharkskin, contained a tallow candle balanced on a

spring to keep the position of the flame constant (Fig. 8). The observer applied his eye

to the body of the instrument and was able to see past the mirror down a series of fittings,

or specula: a narrow tube for the urethra, a bigger one for the rectum, a four-valved one

Fig. 8. The “lichtleiter” or light conductor of Bozzini. One can see the candle used for illumina-

tion immediately next to the eyepiece for viewing.

18 Master, Meng, and Stoller

for the vagina, and a fitting with a mirror on the end for laryngoscopy. Bozzini, an

obstetrician, wanted to use endoscopy for operating on the uterus and to remove foreign

bodies and stones from the bladder (32). The lichtleiter was successfully tested in Vienna,

but it was also clear that candlelight did not have enough illumination to view the

bladder. Moreover, because of local medical politics, further development was blocked.

The lichtleiter certainly accomplished one goal—it spurred the development of endos-

copy by other physicians. Although many other physicians worked on developing endo-

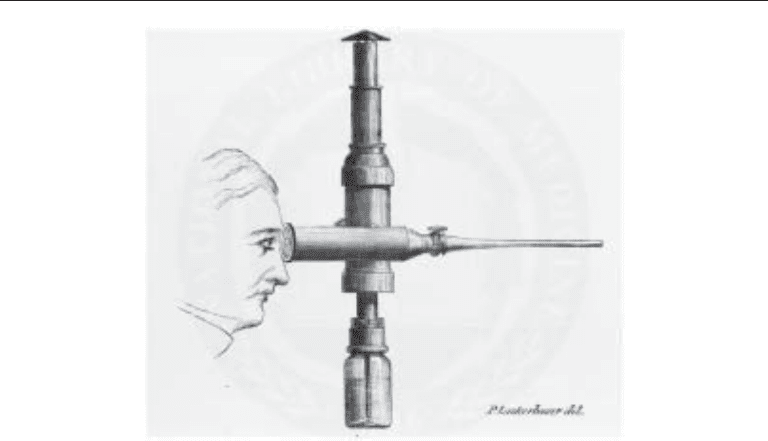

scopic instrumentation, the next leap forward was by Desormeaux, who in 1853

introduced his “l’endoscope” (Fig. 9). This instrument had the advantage of a stronger

light source (initially a paraffin or kerosene lamp), the use of a mirror as a light reflector,

and the ability to introduce working instruments. He was able to make sketches of the

bladder and bladder calculi using this device. Additionally, he diagnosed and treated

urethritis, carried out direct vision internal urethrotomy, and even removed a papilloma

from the urethra. One major problem with this device was the constant fear of burning

the surgeon’s face or the patient’s legs. Francis Cruise of Dublin, a friend of Desormeaux,

encased the instrument in a mahogany box, which allowed for safety from heat but made

it even more unwieldy. The second problem was that illumination still could not reliably

provide for inspection of the entire bladder. Nevertheless, this research spurred others

to develop analogous instruments such that in 1861, Joseph Grunfeld, a dermatologist,

was able to remove a bladder papilloma.

Investigators focused their attention on changing the light source from an external

source to an internal source, which would prove pivotal to the advancement of endos-

copy. In 1867, Julius Bruck, a dentist from Dresden used an electrically heated platinum

loop, inserted into the rectum, to transilluminate the bladder, although Gustave Trouve

of Paris is also credited with this work. Cooling of the loop was a problem, resulting in

rectal burns.

Fig. 9. “L’endoscope” of Desormeaux devised in 1865.

Chapter 1 / Stone Nomenclature and History 19

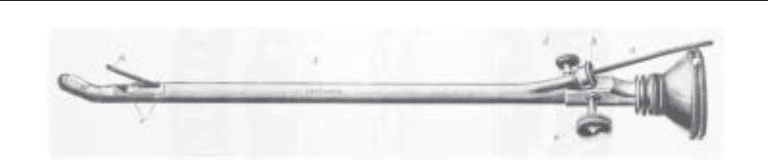

Finally, in 1877 the potential of Bruck’s theoretical advance was realized, and, in

combination with other advances, essentially established the form of a clinically useful

cystoscope as it is used today. The 28-yr-old urologist responsible for this synthesis was

Maximilian Nitze of Berlin. Nearly 90 yr had passed since Bozzini first described his

lichtleiter. Nitze, working with a mechanic and an optician, devised an instrument with

a platinum wire light source at the tip that also had a glass optic system similar to that

of a microscope, allowing for a larger, magnified view of the bladder. This instrument

still produced a good deal of heat and required water cooling. However, once Edison

invented the incandescent electric bulb in 1880, Nitze, as well as Joseph Leiter, produced

the first practical cystoscope in the late 1880s, which was an affordable instrument

(Fig. 10). Additional major design changes took place in the early 1900s and included

the use of water instead of air to distend the bladder and the use of hemispherical lenses

to increase the viewing area (33). The development of fiberoptic instrumentation and the

use of the Hopkins “rod-lens” in the 1950s enabled the clarity of endoscopic images that

we see today. Reviewing this remarkable story, one notes the consistent theme running

through this development, the integration of advancements in physics and optics by

surgeons themselves to make better instruments.

In terms of specific use of instrumentation for stone disease, Kelly published the use

of endoscopy to remove a ureteral calculus, albeit small, in 1895. Kolischer later used

a primitive endoscope and ureteral catheter to inject sterile oil below a stone in order to

facilitate stone passage (32).

The history of flexible urological instrumentation is a recent one. Basil Hirschowitz,

a South African gastroenterologist, again in collaboration with the physicist Hopkins,

produced a flexible fiberoptic endoscope, which enabled him to perform endoscopy in

1957 on a dental student’s wife who was suffering from a duodenal ulcer (34). Interest-

ingly and fortuitously for urologists, American Cystoscope Makers Inc. (ACMI) was the

only company interested in commercializing this instrument. The first reported use of

flexible instrumentation in the urinary tract was actually ureteroscopy and is detailed

later (35).

L

ITHOTRIPTICS

With the severe complications of sepsis, hemorrhage, rectal injury, and death from

surgery, many patients turned to various substances said to be capable of dissolving

stones in vivo. These drugs, taken orally or injected into the bladder with special devices

(Fig. 11), were called lithotriptics, literally “stone-breakers (36).” One of the most

famous, or rather infamous, was sold by Mrs. Joanna Stephens. This resourceful lady has

been reviled as perpetrating a fraud on England in 1739 by her claims of being able to

Fig. 10. Maximilian Nitze’s cystoscope, showing the probe channel, urethral probe, and bulb

illumination.