Marshall L. Stoller, Maxwell V. Meng-Urinary Stone Disease

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

526 Urena, Mendez-Torres, and Thomas

normotensive patients, the resistive index was either stable or decreased (179). Knapp

et al. (179) also reported that post-SWL RI values surpassing 0.690 with 80% sensitivity

and a 70% specificity may predict arterial hypertension. Intrarenal Doppler ultrasound

is useful in patients older than 60 yr to find the high-risk group for arterial hypertension

after SWL secondary to disturbances of renal perfusion as assessed by the RI.

SWL induced hypertension seems to be multifactorial, and none of its proposed

etiology could by itself be responsible for its occurrence. Although DBP has been con-

sistently found to be higher after SWL than in controls, no study has yet demonstrated

its long-term clinical implications. In summary, high risk patients (i.e., altered renal

function, older patients, preexisting hypertension) should be closely monitored before

and after SWL.

COMPLICATIONS OF PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY

The creation of a percutaneous tract specifically for stone removal was first reported

by Fernstrom and Johannson (180) in 1976. Since then, numerous reports have estab-

lished PCNL as a urologic procedure for managing select upper tract calculi. With

subsequent advances in endoscopic equipment and energy sources, which safely and

effectively fragment larger calculi, PCNL is now used as the procedure of choice for

managing most complex renal calculi or even simple renal calculus associated with

complex renal anatomy. Nevertheless, as the number and complexity of PCNL proce-

dures increase, the potential for complications also increases. A high index of suspicion

and prompt recognition and institution of appropriate treatment is fundamental to limit

morbidity.

Factors Influencing Complications

Prevention of possible PCNL complications can be achieved through proper patient

selection and a thorough knowledge of the topographic renal anatomy and its intrarenal

vasculature for establishment of the percutaneous access. Knowledge of appropriate use

and safety profile of the energy sources used for stone fragmentation is essential. Patient

history and physical exam reveal associated co-morbidities, medications, previous sur-

geries, or body habitus that may contraindicate or delay the procedure. PCNL is abso-

lutely contraindicated in cases of uncorrected bleeding diathesis or active urinary

infection. Patients taking anticoagulation medications, (i.e., aspirin, clopidogrel bisul-

fate, and so on) should suspend taking them for 7–10 d before surgery and be screened

for PT, PTT, platelets, and bleeding time before PCNL. Patients with urinary tract

infection should receive bacteria-specific antibiotics and have a negative urine culture

before PCNL. In the event of a UTI and obstruction, proper drainage (i.e., nephrostomy

or ureteral stent) of the obstructed renal unit and broad-spectrum IV antibiotics should

be initiated until the results of the urine culture are known. Once again, if UTI is sus-

pected, PCNL should not be performed until a pretreatment urine culture rules out active

infection. Relative contraindications include “corrected” bleeding abnormalities, ana-

tomic abnormalities (i.e., horseshoe kidneys, pelvic kidneys), medical co-morbidities,

and body habitus (i.e., morbid obesity, severe kyphoscoliosis).

Preoperative imaging studies are important to identify the number and locate the

position of the stones, assess the intrarenal architecture and evaluate the relationship of

the kidney and its surrounding organs for planning the preferred percutaneous access.

Patients with simple renal pelvic or calyceal lithiasis, normal body habitus or absence

Chapter 27 / Complications of Urinary Stone Surgery 527

of complex medical conditions most commonly only need an intravenous pyelogram

(IVP) preoperatively to determine the renal calyx to be accessed. On the contrary, patients

with staghorn calculus, calyceal diverticuli, abnormal body habitus, history of previous

abdominal or renal surgery, and history of recurrent pyelonephritis should also have a

CT scan study. CT scan allows better topographic evaluation of the planned renal access

in relation to the pleura, diaphragm, liver, spleen, and of a retrorenal colon.

Patient Positioning

Proper patient position is achieved by placing the patient in the prone position and

elevating the ipsilateral side 30°. This position helps to ventilate the patient and tends to

bring the posterior calyces into a vertical position, which is helpful during the percuta-

neous renal access (8). Foam padding of the chest, face, arms, and legs, as well as proper

support of all extremities, should be emphasized. These safety measures are crucial to

avoid pressure sores and temporary or permanent nerve injuries or limb paralysis.

Intraoperative Complications

Intraoperative complications can occur acutely during: (1) establishment of the per-

cutaneous renal access; (2) during the percutaneous intrarenal surgery, or; (3) later

during the postoperative period.

B

LEEDING

During Percutaneous Access

Because of the extremely vascular nature of the kidney, bleeding from renal paren-

chyma always occurs to some degree during every percutaneous renal access. Signifi-

cant blood loss is more likely to occur in patients with complex renal anatomy or when

more than one percutaneous access site is needed, such as with treating staghorn calculi.

Intrarenal anatomic consideration is of paramount importance in reducing the risk of

tract bleeding. Therefore, determination of calyceal orientation and choice of the most

favorable calyx for puncture are made before attempting percutaneous access and with

the patient in the prone position mentioned above, using biplanar C-arm fluoroscopy or

real-time ultrasound. The posterior calyx providing the most direct and shortest access

to the targeted stone is preferred. A posterolateral puncture directed toward the papilla

of a posterior calyx would be expected to traverse through the relatively avascular

intersegmental renal zone (181), and consequently be associated with less bleeding.

In a study done using polyester resin corrosion endocasts of the kidney collecting

system and intrarenal vessels to identify the preferred anatomic point of puncture into

a calyx, Sampaio and associates (182) reported that puncture through the infundibulum

of the upper, middle, and lower poles was associated with vascular injury in 67.6%,

38.4%, and 68.2% of the kidneys, respectively. Puncture through the upper pole in-

fundibulum should be avoided because the posterior segmental artery crosses the pos-

terior surface of the infundibulum in 57% of cases (183). Puncture through the fornix

proved to be significantly safer and was associated with less than 8% venous injury and

no arterial injuries. Consequently, the preferred point of entry into the collecting system

is through the renal papilla, along the axis of the calyx. Proper alignment of the percu-

taneous access with the infundibulum’s axis prevents excess torquing with the rigid

nephroscope that otherwise would lead to renal trauma and subsequent bleeding. Direct

puncture into the renal pelvis should be avoided because of the risk of injuring a large

528 Urena, Mendez-Torres, and Thomas

retropelvic vessel, which can be present in one third of cases (157), or one of four

segmental renal arteries, which traverses the anterior aspect of the renal pelvis and

parenchyma.

During Tract Dilation

Beside the percutaneous access, tract dilation is another important step of percutane-

ous renal surgery that needs to be done carefully to minimize intraoperative bleeding.

Several methods of tract dilation are available, including serial coaxial metal dilators

(Alken set, Karl Storz, Culver City, CA), semirigid graded Amplatz dilators (Cook

Urological, Spencer, IN), and balloon dilators. More recently, radially expanding single-

step nephrostomy tract dilators have been described (184). Irrespective of the tract

dilation method used, caution should be taken to dilate the tract only up to the peripheral

aspect of the collecting system under fluoroscopic guidance. The renal pelvis is at high

risk for perforation and the hilar vessels may be injured if dilation is directed too far

medially. Balloon dilators have been found to be associated with less bleeding than serial

dilators (185). Alken dilators, because of their metallic nature, are associated with an

increased potential for tearing the renal pelvis medial wall and causing subsequent

bleeding. Fluoroscopic monitoring under such circumstances is highly recommended.

The Amplatz working sheath tamponades the renal parenchyma and should be kept

within the collecting system after tract dilatation, and excessive angulation should also

be avoided at all times to limit bleeding from parenchymal vascular trauma. Such work-

ing sheaths also allow for safe nephroscopic manipulations while maintaining a low

pressure irrigation environment.

Renal hemorrhage is one of the most common and worrisome complications of per-

cutaneous renal surgery. Although in experienced hands it has an incidence of 1% to 3%,

a transfusion rate of up to 34% has been reported (186–190). Differences in the trans-

fusion rate have been noted to be influenced by different factors, such as operative

technique (balloon dilators vs Amplatz dilators) (185), patient’s status (anemic vs

nonanemic) (190), stone complexity (i.e., nonstaghorn vs staghorn calculus), and num-

ber of access tracts needed (191).

When bleeding occurs during the percutaneous access or during the tract dilation

process, advancement of the nephrostomy sheath usually tamponades the bleeding al-

lowing the procedure to continue. Removal or suctioning of blood clots within the

collecting system is important for stone localization and for working in a clear field, thus

avoiding injury to the urothelial lining. Dark-colored blood stream after stopping the

fluid irrigation is usually of venous origin. If bleeding continues, obscuring endoscopic

vision, placement of an appropriate nephrostomy tube and abandoning the planned

procedure is recommended.

Intraoperative Bleeding

If heavy bleeding continues despite repositioning the access sheath and/or precludes

adequate visibility, temporary interruption of the procedure is advised and tamponade

maneuvers should be initiated.

A large-bore, 26-or 28-Fr Foley catheter should be inserted into the renal pelvis,

clamped, and a diuretic administered intravenously. The nephrostomy should be left

clamped for approx 30 min, while the bleeding and clots are tamponaded. Alternatively,

a 30-Fr balloon dilator can be inflated over the working wire for approximately the same

period of time or a council catheter can be inflated adjacent to a major injured vessel

Chapter 27 / Complications of Urinary Stone Surgery 529

(192) (Fig. 3). If the bleeding is controlled using these techniques and the patient is

hemodynamically stable, the PCNL procedure can be restarted without angling the

working sheath to avoid further bleeding. If unsure, it is highly recommended that further

manipulations be abandoned and the procedure rescheduled.

When bleeding is not controlled with the aforementioned measures and the bleeding

appears to be arterial in nature or when termination of the procedure is decided because

of the hemodynamic condition of the patient, a specialized tamponade catheter (Kaye

Catheter, Cook Urological, Spencer, IN) can be used in combination with serial hema-

tocrit monitoring. The Kaye catheter is a large-diameter, occlusive balloon (36 Fr) with

a built-in 14-Fr nephrostomy tube, which is passed over a 5-Fr ureteral stent. This

catheter tamponades the nephrostomy tract and concurrently and effectively drains the

renal pelvis while maintaining ureteral access. It is usually left inflated for 24 h, although

it has previously been reported to be left inflated for as long as 2–4 d (193,194). More

recently, a new nephrostomy tube that combines the benefits of the re-entry Malecot

design with those of the Kaye tamponade catheter has been developed (195). It has been

shown to be effective in high-risk patients in preventing and stopping bleeding from a

percutaneous access site while maintaining ureteral access.

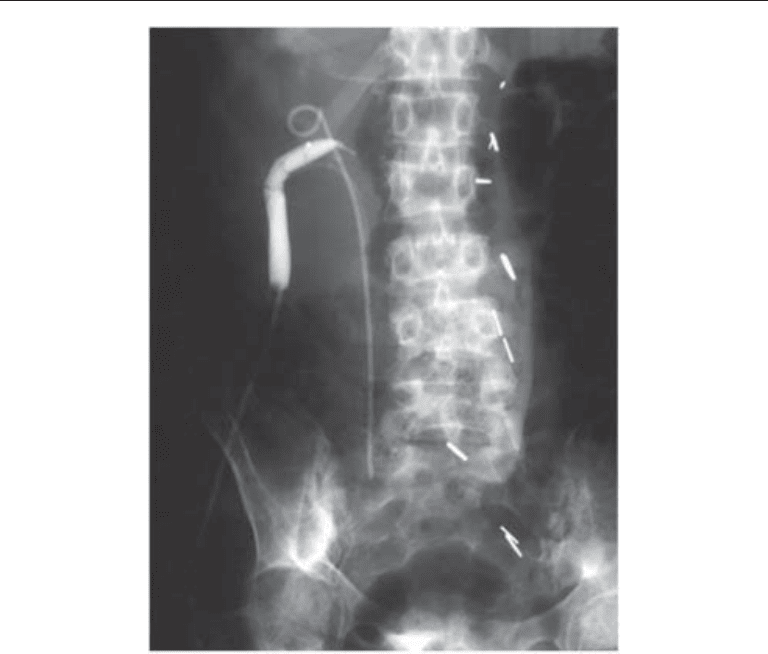

Fig. 3. A 24-mm, 10-cm high-pressure balloon in the nephrostomy tract to control renal hemor-

rhage. Note significant angulation of access tract, causing excessive angulation of Amplatz

sheath during nephroscopy, likely the cause of bleeding.

530 Urena, Mendez-Torres, and Thomas

In cases in which, despite the expectant and supportive measures, there is evidence of

continuous perioperative bleeding (arterial bleeding, dropping hematocrit, continued

need for blood transfusion, hemodynamic deterioration and the presence of expanding

perirenal hematoma), renal angiography and selective embolization of the injured ves-

sels is indicated (188,189,196–201) (Fig. 4). However, most intraoperative bleeding

precluding nephroscopic vision can be managed by placing a 26-Fr nephrostomy tube

and returning at a later date for definitive percutaneous treatment.

Postoperative Bleeding

Delayed postoperative bleeding, either at the time of removal of the percutaneous

nephrostomy drainage or several days to weeks thereafter, can occur secondary to an

arterial laceration (i.e., segmental renal vessels), an arteriovenous fistula, or a pseudo-

aneurysm. Bleeding at the time of removal of the nephrostomy tube from venous origin

can be managed by reinserting the nephrostomy tube and leaving it for a few days until

the urine clears. Bleeding from an arterial source usually does not respond well to this

measure. In case of an arteriovenous fistula or a pseudoaneurysm, bleeding occurs days

to weeks after the PCNL. Patient readmission to the hospital is advised, as is early

stabilization with crystalloids and blood transfusion, if necessary. If the percutaneous

tract is still patent, a balloon dilation catheter, a Kaye nephrostomy tamponade balloon

catheter, or a Council catheter may be placed and inflated to limit the hemorrhage.

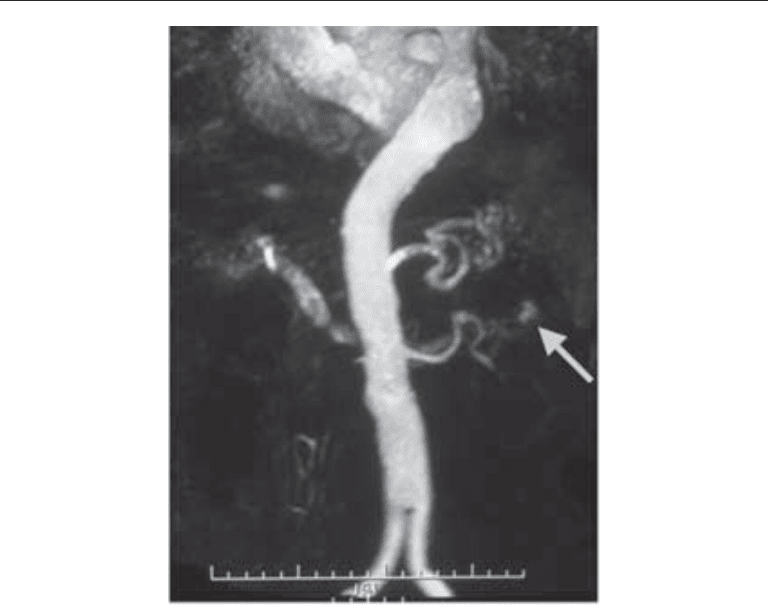

Fig. 4. Magnetic resonance angiography demonstrating a small pseudo-aneurysm and arterio-

venous fistula in the left kidney following PCNL.

Chapter 27 / Complications of Urinary Stone Surgery 531

Immediate renal angiography should be performed to identify the bleeding site or the

location of the arteriovenous fistula or pseudoaneurysm. Subsequently, selective or

superselective embolization is attempted. In experienced hands, the blood transfusion

rate is 2% and the need for renal embolization after PCNL is 1% (202,206) (Fig. 5).

Hyperselective embolization is the least invasive and best treatment for massive hem-

orrhage after percutaneous nephrostolithotomy (200,201). Patients whose bleeding is

refractory to embolization should undergo open surgical exploration, with direct vascu-

lar repair, partial nephrectomy or nephrectomy.

I

NJURY TO THE COLLECTING SYSTEM AND FLUID EXTRAVASATION

Although small perforations to the collecting system almost always occur to some

extent, perforation of the renal pelvis rarely occurs. Because these can lead to some

absorption of irrigation fluid, the use of physiologic irrigating solutions is emphasized.

Major extraperitoneal perforations can be suspected if perirenal fat or other retroperito-

neal structures are seen, or when a discrepancy of more than 500 mL between irrigant

input and output is encountered. In case of intraperitoneal irrigant extravasation, abdomi-

nal distension can be observed. The amount of absorbed fluid also depends on the irrigant

pressure and the length of procedure.

In case of minor perforations, premature termination of the procedure is usually not

necessary if a low pressure irrigation system is being used. Smaller perforations usually

seal within 24–48 h after termination of the procedure (204). However, with more sig-

nificant perforations, termination of the procedure and nephrostomy drainage are advis-

able. Intraperitoneal extravasation, though rare, may be treated by vigorous diuresis or

with the use of peritoneal drainage (205).

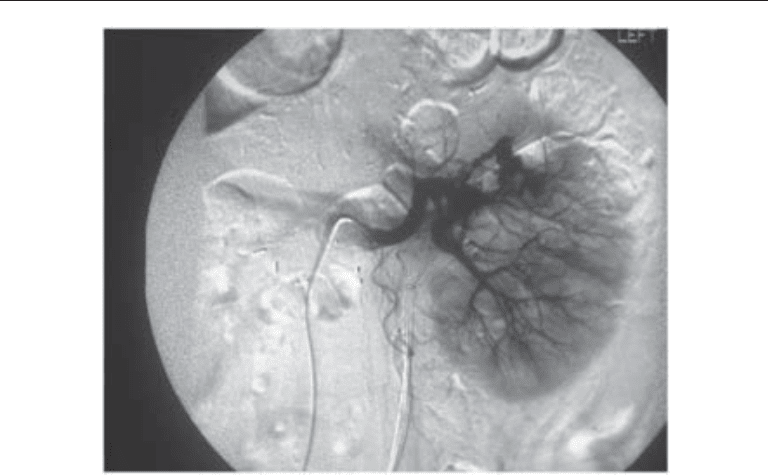

Fig. 5. A digital angiogram is performed to map the vascular supply to the pseudo aneurysm and

arteriovenous fistula.

532 Urena, Mendez-Torres, and Thomas

INJURY TO ADJACENT ORGANS

The retroperitoneal location of the kidney and its close relation to the diaphragm and

pleura, liver, spleen, and right and left colon makes these organs vulnerable to possible

injuries, especially while accessing the kidney percutaneously. Early injury recognition

to any adjacent structure, as well as proper management of it, is vital to avoid further

morbidity or death. Most of these complications can still be managed endourologically

and/or in conjunction with interventional radiology, leaving open surgical exploration

and repair for either major vascular complications or delayed unrecognized complica-

tions.

Lung and Pleural Cavity

Ideally, the renal percutaneous access should be done below the 12th rib and near the

posterior axillary line to reduce the risk of pleural complications. Whenever the pleura

is percutaneously crossed through an intercostal or supracostal approach, there is an

increased risk of developing a pneumothorax, hemothorax, urothorax, or hydrothorax.

Supracostal access tracts are associated with significantly higher intrathoracic and over-

all complication rates compared to subcostal access tracts, and consequently must be

used with caution when no other alternatives are available (206). Preoperative patient

education and informed consents regarding the probability of pleural injury are highly

recommended.

Intraoperatively, pleural violations are suspected by ventilatory difficulties and/or

alterations in the respiratory parameters or with the presence of contrast within the

pleural cavity during the nephrostogram at the end of the procedure. Postoperatively,

ipsilateral chest pain or shortness of breath should also alert the surgeon to the possibility

of a pleural injury. If diagnosed intraoperatively, either aspiration or placement of a chest

tube should be decided at the end of the procedure. When diagnosed postoperatively, the

decision of chest tube placement relies on the patient’s respiratory status and grade of

hemo/pneumothorax in the chest X-ray film. A renopleural fistula is suspected when

there is continuous pleural effusion after chest tube drainage. This can be resolved by

placing a ureteral double-J stent (207). Postoperative pain management and incentive

spirometry are essential after PCNL to allow the patient to breathe deeply and reduce the

risk of atelectasis and associated febrile episodes.

Colon

The retroperitoneal colon is usually encountered anteriorly or anterolaterally to the

lateral renal border. Therefore, the risk of colon injury is usually low. Colonic perfora-

tion may occur when the puncture site is placed lateral to the proposed posterior axillary

line or in the rare event of a patient with a retrorenal colon. Displacement of the colon

posterior to the kidney with increased risk of colon perforation is seen in elder patients

with chronic constipation or patients with other causes of distended descending colon,

patients with previous major abdominal surgery (i.e., jejunoileal bypass resulting in an

enlarged colon), and in thin female patients with very little retroperitoneal fat (208,

209). Other factors increasing the risk of colon injury include patients with left renal

disease, mobile kidneys, anterior calyceal puncture, previous extensive renal surgery,

horseshoe kidney, and kyphoscoliosis (17,181,203,210,211). Ultrasound-guided renal

percutaneous access can be performed in patients with increased risk of having a

retrorenal colon (212). A preoperative CT scan in the prone position is recommended if

any possibility of colonic injury is suspected.

Chapter 27 / Complications of Urinary Stone Surgery 533

Colonic perforation should be suspected if the patient has intraoperative or immedi-

ate postoperative diarrhea or hematochezia, signs of peritonitis, or passage of gas or

feces through the nephrostomy tract (213). Otherwise, a postoperative nephrostogram

before nephrostomy removal can reveal the presence of colonic contrast. In the absence

of peritonitis or sepsis, most extraperitoneal colonic perforation can be successfully

managed conservatively (214). An indwelling Double J ureteral stent is inserted, the

nephrostomy tube withdrawn under fluoroscopic guidance into the colon, and a Foley

catheter is left in place in the bladder to maintain a low urinary pressure system. The

patient should be given broad-spectrum antibiotics or triple antibiotic coverage and

placed on a low-residue diet. This allows the renal collecting system to heal and the

medial colonic wall to close. After 5 to 7 d, if the colostogram shows neither extrava-

sation nor colonic communication with the collecting system, the Foley catheter is

removed and the colostomy tube withdrawn, but still kept as a drain. Two to three days

later, when the lateral colonic wall is expected to be closed, the tube is then completely

removed. In case of intraperitoneal colonic perforation, peritonitis, sepsis, or failed

conservative management, open surgical exploration should be performed.

Liver and Spleen

The liver and spleen may also be at risk of being injured during percutaneous access.

In the absence of splenomegaly or hepatomegaly, injury to these organs is extremely rare

with subcostal and lower pole punctures. The risk may be somewhat greater with upper

pole punctures, especially if the puncture is performed during inspiration and/or if the

puncture is above the 11th rib (215–217). When performing upper pole punctures, a skin

puncture site at the lateral border of the paraspinal muscles reduces the risk of liver or

spleen injury.

Transhepatic percutaneous renal access is not without major risk, because it is similar

to percutaneous procedures of the hepatobiliary system. Transhepatic tract dilation poses

the risk of injuring the hepatic vasculature. However, in the absence of active bleeding,

it can still be managed conservatively, leaving a transhepatic nephrostomy postopera-

tively, as well as an indwelling ureteral stent and bladder Foley catheter. The ureteral

stent and bladder Foley catheter should be kept in place after the nephrostomy tube is

removed to reduce the risk of renobiliary fistula. Active bleeding or injury to a major

hepatic vessel requires open exploration and repair.

Splenic injuries are suspected in hemodynamically unstable patients with intra-

abdominal bleeding undergoing left PCNL. The diagnosis is conducted with intraopera-

tive abdominal ultrasound or with a postoperative abdominal CT scan. Although conser-

vative management can be used in some patients with nonexpanding subcapsular

hematomas, in most patients splenectomy is performed (218).

I

NTRAOPERATIVE ENERGY SOURCE RELATED INJURIES

Independent of the type of lithotriptor used for PCNL, potential energy-related com-

plications can be produced if improperly used. First, a thorough knowledge of the indi-

cations and safety profiles of the energy source being used is essential. Second, under

no circumstance should the energy source be used unless there is proper visualization of

the working field. If the working field is bloody or the presence of clots precludes

adequate visualization, the case must be interrupted until proper hemostasis of any

bleeding site is achieved and clots are removed.

534 Urena, Mendez-Torres, and Thomas

Ultrasonic lithotriptors are rarely associated with energy-related intracorporeal com-

plications. Nevertheless, caution is urged to not dig the probe against the urothelial lining

to avoid perforation and bleeding. Similarly, overheating of the probe tip should be

avoided. Periodic procedure interruption allows for crystals in the probe to cool, which

prevents thermal injuries that can lead to strictures, especially at the UPJ. Overheating

of the crystals can also cause the device to malfunction.

Electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) is also relatively safe to use, although it can cause

bleeding and renal pelvis perforation. Nephrostomy tube drainage, either alone or in

conjunction with an indwelling ureteral stent, usually helps to heal the renal pelvis

perforation adequately within a few days. EHL consequently has not been found to be

associated with UPJ strictures.

Candela and Holmium laser lithotriptors have a high safety profile and a low compli-

cation rate, such as urothelial lining perforation (219). Holmium laser technology pro-

duces less urothelial penetration, thus posing some advantage over other laser modalities

(i.e., tunable dye laser) in terms of causing less renal pelvis perforation when properly

used. However, the Holmium laser, if directly in contact with transitional cell mucosa,

can cause thermal injury. Also, direct contact of the Holmium laser can cut guidewires

and stone baskets, and thus, direct contact with paraphernalia should be avoided.

A new lithotriptor composed of a Lithoclast Master and an ultrasonic device (EMS,

Nyon, Switzerland) has been used for PCNL procedures. Clinical and laboratory assess-

ment of this newly developed pneumatic lithotripsy device has validated its efficacy in

fragmenting stones of all compositions and its overall safety associated with clinical

application (218,220,221).

COMPLICATIONS OF URETEROSCOPY

Since its initial description by Young in 1912, ureteroscopy has come a long way and

has gained widespread acceptance as an option for the treatment of multiple ureteric and

renal conditions. Further advances in technology have led to the introduction of smaller

caliber ureteroscopes with the capacity to accommodate accessory instruments neces-

sary to perform diagnostic and therapeutic upper urinary tract procedures. Also, the

advent of fiberoptic technology has provided the opportunity to create flexible scopes

capable of reaching the renal pelvis and calyceal groups. Although ureteroscopy is being

used for multiple purposes—including evaluation of filling defects in the upper urinary

tract, evaluation of positive urine cytology, incision of strictures, uretero-pelvic junction

obstruction, and ablation or resection of urothelial malignancies—the vast majority of

ureteroscopic procedures are performed to fragment and extract ureteral stones.

Since its introduction into routine clinical practice in the early 1980s, the complica-

tions and adverse events associated with ureteroscopic procedures have decreased dra-

matically. Smaller caliber ureteroscopes, reliable and safer fragmentation devices and

paraphernalia, and, above all, surgeons’ experience in these procedures should be given

credit.

Ureteroscopy, independent of its indications, should always be performed with the

greatest margin of safety possible. To accomplish this, several steps should be performed

during the procedure, including:

1. Complete cystoscopy and emptying of the bladder;

2. Retrograde pyelogram to evaluate ureteral anatomy and delineate plan of action, when

indicated (Fig. 6). An adequate intravenous urogram may suffice;

Chapter 27 / Complications of Urinary Stone Surgery 535

3. Placement of a safety wire under visual and fluoroscopic monitoring (we prefer to place

an Amplatz Super Stiff

TM

guidewire because it straightens the ureter and facilitates

access to the upper ureter);

4. Balloon dilation of the ureteral orifice and distal ureter only if necessary;

5. Careful passage of the rigid ureteroscope alongside the safety wire;

6. Careful passage of the flexible ureteroscope over a second guidewire under fluoroscopic

imaging;

7. Judicious use of ureteral access sheath to facilitate recurrent and safe passage of rigid

and flexible ureteroscopes.

The most critical step in ureteroscopic access is the placement of the safety wire.

Fortunately, several different wires are available to facilitate access to the ureter. Size,

tip design, surface coating, and shaft rigidity are the main characteristics that differen-

tiate one guidewire from another.

After ureteroscopic access is obtained and the stone is directly visualized in the

ureteroscopic field, the calculus is extracted intact or fragmented under direct vision for

extraction. Several different devices are now available for stone fragmentation in the

ureter:

1. Ultrasonic lithotriptor, which uses an electric current applied to a piezoceramic crystal

creating vibrational energy that is transmitted to the stone via a rigid hollow probe for

fragmentation and aspiration. This technology is very safe and activation of the probe

in contact with the urothelium for short periods of time results in minimal tissue injury.

The use of this technology in the ureter has decreased because of the advent of flexible

laser fibers.

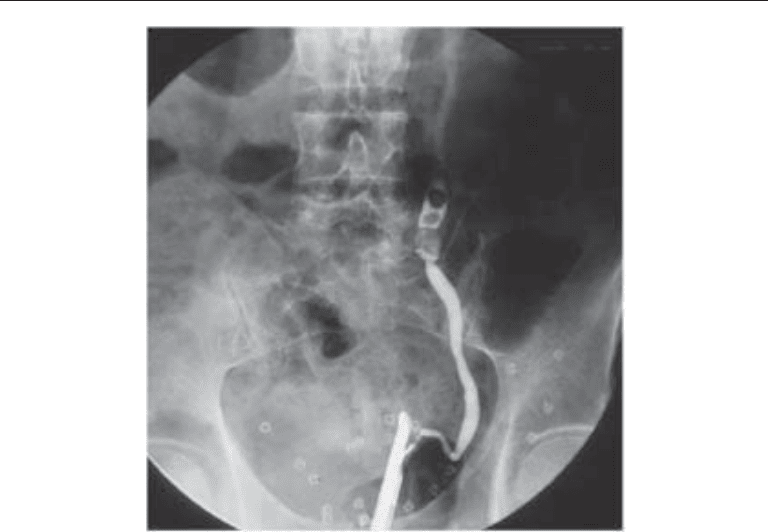

Fig. 6. Left retrograde pyelogram performed to delineate the course of a tourtous ureter associ-

ated with an impacted stone.